Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.20 Maringá 2020 Epub 01-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e128

DOSIER

Histories of our country: on the civic project of construction of the Brazilian nation through print

1Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil.

This article presents an excerpt from a study on school reading books circulating in Brazil in the first decades of the republican period. Specifically, it has been examined the book Historias da nossa terra (Histories of our country), by Julia Lopes de Almeida, published in 1907. A question has guided the study: howHistorias da nossa terra was inserted in the morphology of school reading books, whose materiality and content conveyed a civic and patriotic pattern proposed as referential to the republican Brazilian nation? The theoretical ground can be found in studies of history of education and cultural history. The book was aligned with schoolbooks of the period and contributed to the construction of the Brazilian nation by means of print.

Keywords: history of education; Julia Lopes de Almeida; civic and patriotic pattern

Este artigo apresenta um recorte de um estudo sobre livros escolares de leitura em circulação no Brasil nas primeiras décadas do período republicano. De modo específico, examinou-se o livro Historias da nossa terra, escrito por Julia Lopes de Almeida e publicado originalmente em 1907. O estudo orientou-se pela seguinte questão: de que modo Historias da nossa terra e inseriu na morfologia dos livros escolares de leitura, cuja materialidade e conteúdo veicularam um padrão cívico e patriótico referido à nação brasileira republicana? A fundamentação teórica ancorou-se em estudos da história da educação e da história cultural. O livro se alinhou aos livros escolares do período e contribuiu para a construção da nação brasileira por meio do impresso.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; Julia Lopes de Almeida; padrão cívico e patriótico

Este artículo presenta un extracto de un estudio sobre libros de lectura escolares en circulación en Brasil en las primeras décadas del período republicano. Específicamente, se examino el libro Historias da nossa terra, escrito por Julia Lopes de Almeida y publicado originalmente en 1907. El estudio se guió por la siguiente pregunta: ¿cómo se inserto Historias da nossa terra em la morfología de los libros de lectura escolares cuya materialidad y contenido transmitían un patrón cívico y patriótico referido a la nación republicana brasileña? Los fundamentos teóricos se basaron en los estudios de la historiade la educación y la historia cultural. El libro se alineó con los libros escolares de la época y contribuyó a la construcción de la nación brasileña a través de la impresión.

Palabras clave: historia de la educación; Julia Lopes de Almeida; patrón cívico y patriótico

Introduction

Throughout the twentieth century, there has been a growing interest in school reading books, both as a source and as an object of investigation in the context of historical research. According to the historiography of written culture and school culture, the first investments in this direction occurred in Germany, coordinated by the historian Georg Eckert, at the end of the Second World War. Currently, it continues at the George-Eckert-Institut für Internationale Schulbuchforschung - Georg Eckert Institute for international research on schoolbooks. However, the investigation was not restricted to Germany since researchers from other countries became interested in the subject, expanding approaches, methodologies and research instruments related to this study. The creation of research centers, whose databases provide a wide assortment of handbooks and textbooks, is an important contribution in this direction. Worth of mention are the efforts derived from systematizations at EMMANUELLE (Banque de Donnés Emmanuelle - Institut Nacional de Recherche Pédagogique), in France, founded in the decades following the end of the WWII, directed by Alain Choppin; at the Spanish MANES (Centro de Investigación MANES - Escuela Escolares), from the HISTELEA Program (Historia Social de la Enseñanza de la Lectura y la Escrita en Argentina); and at the Brazilian LIVRES (Database of Brazilian Schoolbooks), which started in 1994, linked to the Centro de Memória da Educação da Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo (FEUSP - Center of the Education’s Memory of the Faculty of Education, at São Paulo State University)29.

As inferable from the importance attributed to the database LIVRES, particularly in Latin America and in Brazil, social and education historians surrounded themselves of this kind of research, which has provided for multiple approaches, with emphasis on school cultures, written cultures, systems and methods of teaching, curricula, reading practices, and so on. As a result of a broader investment in studying this kind of cultural object, it has been possible to amplify approaches, methods, and investigation instruments.

In Brazil’s case, the growing number of research in the area indicates efforts, including the establishment of a more precise morphology in relation to school reading books (Batista, Galvão & Klinke, 2002), as historiographical researches show significant oscillation regarding nomenclature-pedagogic handbook, textbook, schoolbook, children’s book, graded reader series, reading book, school reading book-possibly because this source of material for historical studies is relatively new, because of the disposable nature of this kind of school material or even because of the diversity of approaches it allows, as shown by researches on nomenclature developed by Alain Choppin (2002, 2004), and Augustin Escolano (2012). The multiple nature of the approaches in relation to this object and source can be seen in articles, works and books dealing with the theme. To better illustrate this argument, note the occurrences of terms related to schoolbooks on three different axes within the scope of the VIII Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação: matrizes interpretativas e internacionalização (Brazilian Congress on the History of Education: interpretive matrices and internationalization30), which was held at the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, on 29 June to July 2, 2015. The axis 3-Sources and Methods in History of Education-accounts for more than one occurrence: pedagogical handbook, textbook, and schoolbook; the axis 6-History of School Cultures and Disciplines-conveys other occurrences: reading books, textbooks; the axis 10-Educational Built Heritage and Cultural Materials at School-in its turn, comprises the variants children's books, textbooks, and graded reader series. From this perspective, it can be inferred that the study of school reading books could relate both to sources and methods and to the history of school cultures, educational heritage or cultural materials at school, which partially demonstrates multiple interfaces of the object to be examined.

In the first section of this study, we examine how the writer Julia Lopes de Almeida mobilizes national symbols and the social representations associated with motherhood and paternity in Historias da nossa terra, as an introduction of topics related to national identity and the reconfiguration of the Brazilian nation, according to the ideas from the first decades of the republican period. In the second section, we demonstrate how the narrative model that addresses travelling around Brazil seeks to affirm the notion of national identity and, by derivation, the civic and patriotic sentiment that provides a unique physiognomy in relation to the Brazilian Republic. In the final remarks, we return to the idea of a writing project led by Julia Lopes de Almeida and the highlight of this school reading book within the scope of her project.

This is a good little book, in which Julia Lopes de Almeida tells us 'Histories of our country'. 'Tells us' is a way of saying it because, to tell you the truth, the book is not intended for children over twenty, which does not mean that it would not enchant and delight those in their 40s, and even the macrobian ones (O Paiz, 1907, p. 2, emphasis added by the author).

Civic pantheons of the Brazilian Republic in Historias da nossa terra 31

On June 12, 1907, the newspaper O Paiz, founded by a Portuguese man named João José dos Reis Júnior, in 1884, and widely circulated in the then Federal District32, announced a book by Mrs. Julia, in its column intitled “Palestra” (Lecture), published on the second page of the well-known newspaper. “Palestra” was not just any column. Among other subjects, it discussed editorial news, emphasizing graphic features, content, and it would also indicate the intended audience for the work under discussion. Historias da nossa terra was fresh news, then. It could be novelty from an editorial point of view, but not from the production of Julia Lopes de Almeida, a writer known for her wide range of titles33. In the literate society of the period, she used to be presented as the wife of the academic Filinto Almeida, and the perfect family mother. However, as recorded in reference books and studies on the writer (Schumaher & Brasil, 2000; Muzart, 2015; Stasio, Faedrich, & Ribeiro, 2016), she wrote short stories, novels, chronicles, lectures, and schoolbooks. When it comes to her ideas, the author defended abolition of slavery, relative autonomy of women by the standards of the time, women’s suffrage, opening of new schools, improvements in public administration, and access of the population to public libraries. She wrote

And more, much more people, would go to that house to do readings they cannot do in theirs, if the Library were open until nine or ten at night; but it closes at four! I do not know or care about the regime by which other public libraries in the world are kept. Each country has its use. In our country, there are many classes who only have spare time for reading and studying at night. The commerce workers, homeless boys, without comfort enough that give them an hour at night to read in peace. Only in the Library they would satisfy the plead for food their spirit makes to them and cultivate it without sacrifice. Mr. Minister of the Interior must solve this problem as soon as possible: since we have a public library, it is mandatory that it serves the public, without exception (Almeida apud Stasio et al., 2016, p.143)34.

Despite her wide insertion in the public sphere, Julia Lopes de Almeida was represented, above all, as wife and mother. Indeed, according to the literary criticism of the period, she should be remembered mainly for books and handbooks addressed to mothers and maidens, which was the case of Book of brides35, appreciated by the critic and academic Lucio de Mendonça, in the pages of the Almanaque Brasileiro (Brazilian Almanac) in 1897 36.

Concerning Historias da nossa terra, as it was a work intended for school education, it had been edited that same year of 1907, by Francisco Alves & Cia. (Rio de Janeiro), and Aillaud Alves & Cia. (Paris and Lisbon). If, on the one hand, the materiality and content of the work seemed to be intended for a school audience, on the other, the request for 77 copies of the stories from Mr. Francisco Alves, by the stockroom of primary schools of letters, in April 1915, attested that the book circulated in several schools, at least those located in the Federal District37.

In addition, the Francisco Alves bookstore, since the end of the 19th century, took chances in this editorial segment-textbooks38-and, as scholars explain in the context of publishing history in Brazil (Hallewell, 2012; Bragança, 2000), having a book edited by Francisco Alves was an advantage because, due to the legitimacy of the publishing house that he directed in the segment of schoolbooks, this would make the adoption of the publication by primary schools of the period more likely.

From the epigraph to this section, one could notice the special address of the work to children “[...] the book is not intended for children over twenty [...]”, without, however, excluding people of all the ages that would be willing to listen to the stories of our country, told with the “[...] crystalline and pure prose [...]” of the author of Ancia eterna (1903). Artur Azevedo (AA), journalist and playwright39, was the one who signed the column 'Palestra' and, therefore, that favorable critique of the work. To give more credibility to his recommendations, he transcribed the first “short story”, A nossa bandeira (Our flag), which functions as a gateway to the volume written in a tone that is both maternal, civic, and patriotic.

It was a 223-page school reading book composed with different discursive genres, such as composition exercises, exemplary stories and letters. The book was dedicated to the children of Julia Lopes de Almeida, which allows it to be aligned with written schoolbooks, according to a modern maternal pedagogy (Gomes, 2016)40, in other words, according to a rhetoric marked by advice, warnings and moral lessons. This style is evidenced not only in the dedicatory sheet: "To my children". The rhetorical tone of the maternal and paternal relationship could also be noticed in the content of the compositions, as in Minha mãe (My mother) and Meu pai (My dad), chapters inserted in the introductory part of the work. Minha mãe is a composition extracted from the notebook of the character Henrique. He spared no praise in describing the maternal figure: ready to assist the child in all situations-day and night-to guide, to advise to understand the teachers and respect them. As the only possible horizon, the mother would want the well-being and the grand future of her children. Warning, counseling, and forgiving were, then, the expected actions of an exemplary mother described on the pages of that school reading book. When it comes to the father, the second key of the family cell described there, he was indeed depicted as the myth of the hero. Whether he was strong or weak he should always go to work outside the home. To guarantee that his children would never be in need, he would labor from morning to dusk. In one word it was built the representation of the provider of the family and, by extension, of the nation, which was to be constructed with the republican ideas of the first decades; father, provider, and hero, once he would be willing even to die to spare his children's lives.

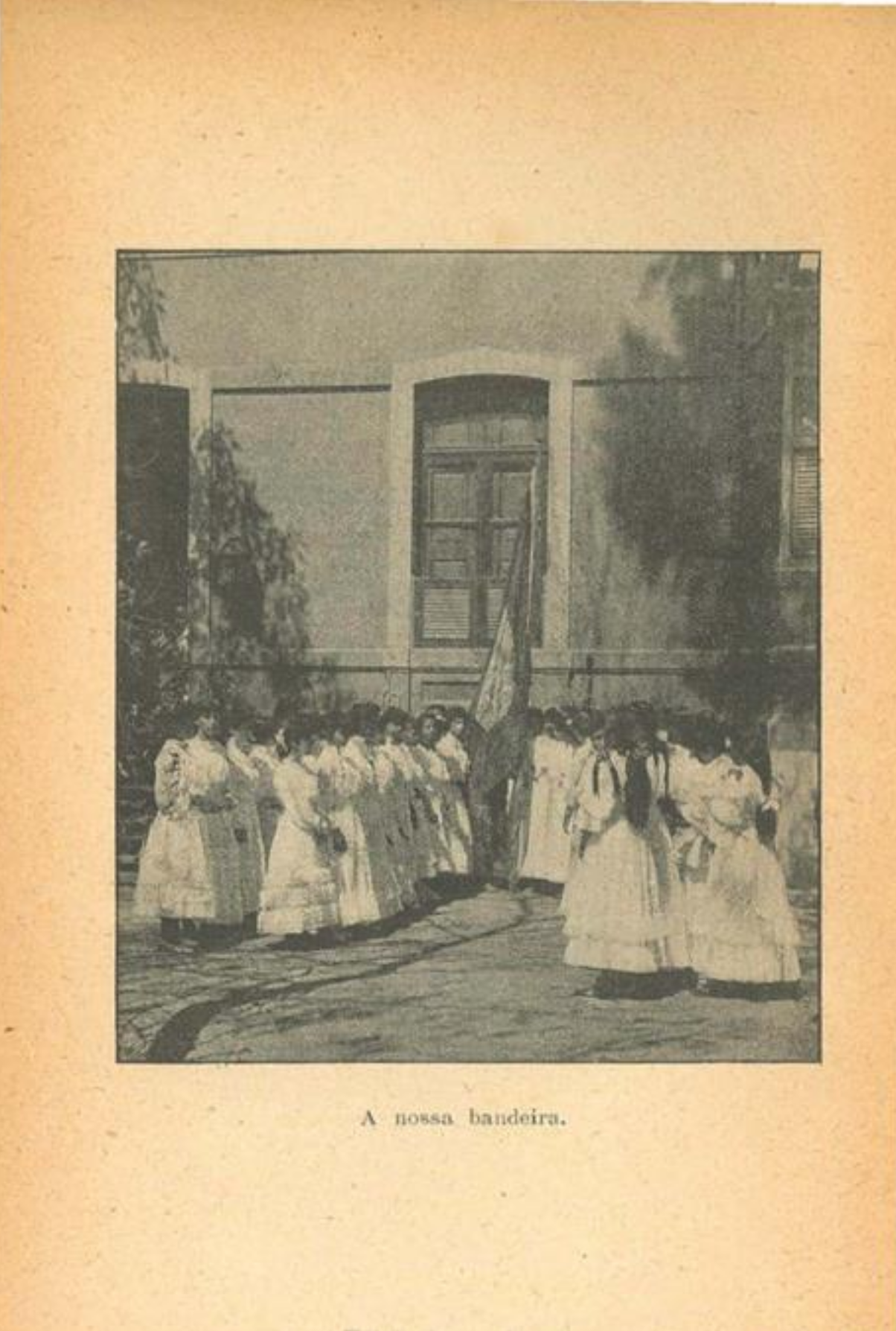

When it comes to material, the book is abundantly illustrated by photographs featuring school culture of that time, as well as landscapes, school logbooks, and commemorative monuments, which provided the right tone for the work41. A photograph, composed predominantly of girls uniformly dressed in party clothes and lined up next to the national flag, preceded the first text: Nossa Bandeira (Our flag). The background calls attention for the architecture of large school buildings, especially due to the large dimensions of the front wall, door and windows, as shown in figure 1, below.

As far as the narrative style is concerned, it was not exactly a short story. It would be better defined as a composition exercise, a didactic device used in schoolbooks from that period, whose main stylistic feature was based on detailed description of historical facts and abundant use of adjectives, which attributed to the narrative style characteristics both patriotic and nationalist. Therefore, one should not lose sight of this type of morphology in school reading books of the first republican period. To keep it up to just two examples, it is possible to identify this morphology in Cuore, (Heart) by the Italian Edmondo De Amicis, originally edited in 1886, and translated into Portuguese as Coração (Amicis, 1954), by João Ribeiro, in 1891 and in Através do Brasil42 (Through Brazil), launched by Manoel Bomfim and Olavo Bilac, in 1910. Both books were also published by the Francisco Alves’ publishing company, notably for their school nature. Coração is written as a diary in which Enrico's school life is narrated, in the post-unification period of Italy, and whose central theme was to educate young people by means of examples of virtue and courage, mobilizing moral and patriotic values43. Através do Brasil, in its turn, was designed as a reading book addressed to primary schools. In addition to transmitting content of an encyclopedic nature, the book presupposed a set of values of a formative nature in line with the nationalist and civilizing ideas of the first republican decade in the country.

However, only Historias da nossa terra received a positive evaluation by the historian Manoel Curvello de Mendonça44, in 1907, when it was published. The book, according to his view, was a document on pedagogical studies about Brazil, through which the teacher would be able to transmit good gestures of patriotism, which the Italian work was far from providing to small Brazilian readers.

How many explanations can the solicitous teacher offer about statements that awaken and indicate them? Here is the best pedagogical virtue of reading compendiums. The Italian schools shuddered with joy and love, in the face of that loving 'Heart', by Edmondo De Amicis, which we translated and took advantage of in the lack of similar national work. Well then, 'Historias da Nossa Terra' fills this gap, singing the patriotic note that the foreign book could not chant (O Paiz, 1907, column 1, emphasis added by the author).

Julia Lopes de Almeida, despite being a novelist and short story writer for adult readers, knew the field of school reading books, as well as fiction books addressed to children. We must remember the fact that she wrote “Contos infantis” (Short stories for children) in co-authorship with her sister, Adelina Lopes Vieira, in 188645, whose circulation in schools in the Federal District was also expressive: 102 copies ordered from Mr. Francisco Alves by the stockroom of the primary schools of letters, in 1915, was no small feat46. But, despite having written fiction books for children, she disputed her insertion in this field, which was then taking form in Brazil, with other cultural mediators and producers of symbolic goods (Sirinelli, 2003), in the first decades of the republican period, as indicated by a research on the subject (Silva & Pinto, 2018). Therefore, it is important to locate “Historias da nossa terra” (1907) between the tradition of Italian work in circulation in Brazil, since 1891, and the permanence of this style of text identified in the adventures in Através do Brasil, by Bomfim and Bilac, published in 1910.

Still on the text “A bandeira” (The flag), it should be noted that the four official symbols of the Federative Republic of Brazil are the national flag, the national anthem, the coat of arms of the republic and the national seal47. In the initial part of the work, Mrs. Julia aimed to make the hearts of the readers vibrate by the exaltation of two of these symbols: the flag -in the first image and in the content description-and the republic coat of arms, in the final image of the composition. Through the narrative, she highlighted the flag’s singularizing colors-green, blue, yellow-relating them to the nature and to the universe. This discursive strategy was well aligned with the scope of her project since by means of her laudatory tone she would invite children from south to north to be proud of the national identity feeling arising from the national symbols uniting them, particularly when people from other countries were concerned.

Our flag is like a fraternizing pallium over the heads of all Brazilians. Let us unite to honor it in its greatness and so may it always be for us, in addition to the symbol of the Mother Land, the symbol of Good, of Reason, of Justice (Almeida, 1911, p.8).

According to this excerpt, the national flag is defined by the writer as a broad and fraternizing mantle thrown over the heads of all Brazilians, from north to south of the country. It is expected from a national symbol exactly this kind of power to achieve certain effects: the ability to translate the collective imagination; the capacity of fostering the nation's civic sentiments. And the national flag, a fraternizing pallium, seems to have worked properly in that context.

The book contains another composition with similar content: “Nossa língua” (Our language), having as a backdrop, on the one hand the school, but on the other teachers and students. The composition exercise, this time, was preceded by a photograph of a mixed class, with uniformed students, in a large room furnished with twin school tables, with a clock on the wall, with a locker and maps. This was the ideal scenario set up for a character represented as an old man, master of the master, to discuss the values of the mother tongue. The language was described as the element that most characterizes the country. Indeed, it should be better known by all who use it, since it constitutes, according to that idea, the subjectivity, identity and tradition of the Brazilian people. The dimensions of race and nationality of a people conveyed by language were emphasized from another angle. In summary, it was important to emphasize in the school reading book “Historias da nossa terra” that language and homeland consist of equivalent notions. Not only for these reasons should the Brazilian people feel extreme pride of their national language. Above all, there would be the singular trait of perfection, which no other language would deliver. “With an extremely varied sound, opulent in its words, malleable as wax or hard as diamond, the Portuguese language is the most beautiful expression of human intelligence” (Almeida, 1911, p. 13).

The writing of history related to republican Brazil was anchored, notably during this period, in the project of producing a memory capable of conferring original identity to the Brazilian State. Despite the narrative of Mrs. Julia contributing to erect the Republic as a new regime, which produced civic and patriotic symbols, the theme of the national thing had already been widely mobilized in the Brazilian Empire, as well as that of the formation of the nation itself48.

However, it should be considered that, just like the national flag, the mother tongue was redefined in that narrative as the civic pantheon of the Brazilian Republic. We agree with Anderson (2008), when he warns about the nation-building policies of new States, alluding to the fact that it was necessary that the educational system would forge a type of nationalist ideology through the mass media. This was the tone adopted by Julia Lopes de Almeida's skillful pen in the opening of her work, as shown by the symbology in photograph 2.

After reading the two introductory texts on the national symbol and identity-flag and language-and observing the cell of the Brazilian nuclear family, one could then discover the Brazilian territory. There were more elements to be explored in Historias da nassa terra.

A trip around Brazil by means of exemplary stories and letters.

The book is structured by means of eighteen exemplary stories and eight letters. The texts, although they included secondary plots, such as poverty, abandonment, resilience in the face of adversity, each was part of a long journey around the national territory. The trip begins with a school excursion in Rio de Janeiro, which was then the Federal District, led by the director and teacher of the school, and starred by the boy Anthero. He writes a letter to his father to report his impressions. In this letter, he discuss the wild nature transformed into civilization by the hands of man, as the director had told him: the Pão de Açúcar, the Military School49-guardian of the defense of the country-the Institutes of the Blind50, of the Deaf and Mute51, the Pasteur Institute52. It was important to emphasize that the elderly, children and the sick, in particular, would benefit from the actions carried out within the scope of the legitimate institutions highlighted there, be it for the defense of the country or for health assistance to the population. Rio de Janeiro, capital of the Brazilian Republic, symbolized in the eyes of the narrator and other characters described there the strength of human work in the light of science and arts. It was not by chance that the first stop of the exploratory journey around the vast national territory would be Rio de Janeiro.

However, the trip was not just about a contemplative exaltation of the richness and natural beauty of the country. It was important to know and explore the territory marked by a new century, in the process of celebrating the centenary of Brazil's independence. Language, Geography, Literature, History, based on heroes and major events, were then resized, as a way of rewriting the history of the new country under the republican regime. It was about being and writing a history with a predominant narrative, according to which the independence and emancipation of the Brazilian people were fully achieved under the republican regime. However, it should be noted that the Republic had instituted a political rupture. The search for a collective identity for the country and the nation-building project must be understood with nuances arising from the imperial regime. All these elements, therefore, denote a sober and gradual process of emancipation. In view of this project on the horizon, the reader of “Historias da nossa terra” arrived in other Brazilian cities.

The next place that deserves note is Vitória, Espírito Santo. At the bottom of the scene, two students sit next to a poor blind woman and discuss memorable facts related to the History of Brazil. The topic of civilization versus barbarism is recurrent. It was necessary, according to the narrator, for the Portuguese to arrive in Brazil and bring civilization to the Indians, described as 'bloodthirsty', 'savages', 'nomads', as they did not cultivate attachment to inhabited places. The pantheon of civilizing heroes should be remembered as a monument: Pedro Álvares Cabral, Pero Vaz de Caminha, Friar Henrique de Coimbra. As a moral effect motto to be remembered, they emphasized: “Civilization sweetens the character and makes men good” (Almeida, 1911, p. 27).

The trip, however, is marked by abrupt displacements, without following a predictable path. In the tale “O grumete” (The cabin boy), for example, the adventure of a fatherless boy called Manoel, from Pará, whose greatest feat is to embark on the Tocantins steamboat in search for work to support his mother and his sick sister. The author makes use of a curious hybrid resource by crossing facts from the historical narrative related to the country, and told by an old paralyzed man, with the fictional narrative starring Manoel, raised as a hero for saving the old man from a storm that hit the steamboat Tocantins. Financially rewarded for his achievement, he was able, after all, to return to Pará transformed.

It should be noted how Julia Lopes de Almeida recovers in this story and in some others53 that compose Historias da nossa terra the bildungsroman structure. Bildungsroman designates the type of romance in which the character's physical, moral, social, and political development is narrated in detail from childhood to maturity54. By suffering all kinds of trials, they ripen as a result of the difficulties they face55. An interpretation suggested by the reading of this work as a whole remits to the development not only of the character Manoel, but to the geographical, social and political transformations that occurred during the constitution of the Brazilian nation. It is not by chance that, in the first decade of the 20th century, the most diverse diagnoses referring to Brazil as a project under construction were being read. In the face of adversities of all kinds, it could soon become a republican nation. To put it shortly, the country would transform and achieve progress, just like the character described in “O grumete” and in other stories narrated by Julia Lopes de Almeida in Historias da nossa terra.

With a view to raising the Republican nation in a powerful way, it was important to defend the construction of national unity. We agree with Carvalho, when he points out the emergence of the nationality theme by means of the novel O Guarani, by José de Alencar, in 1857, whose plot focuses on the symbolic union between a young blond Portuguese woman and an Indian. The narrative depicted the union of two races and the “[...] bases of a national community with its own identity” (Carvalho, 1990, p. 23). However, in the republican period, we are still facing a project that is difficult to carry out, mainly due to the vast territorial extension of the country. Thus, one can better understand the insertion of the short story “O sino de ouro” (The golden bell) in this set of texts that gave form to the work56. This time the reader moved to São Luís, Maranhão State, where Maria Mathilde, depicted as an old madwoman, had the ambition to have a high tower built, where a huge golden bell would be. The name of all Brazilian states would be engraved on it with precious stones, as if it were the “[...] beating heart of Brazil” (Almeida, 1911, p. 69). In that fictional narrative, unity among all the states of the federation could perhaps be achieved, were it not for the premature death of the narrator and the frayed project, reflected only as a mirage in the middle of the sky.

However, according to the preliminary project outlined in O sino de ouro, the reader is invited to visit the other Brazilian states. The adventures and historical episodes are recurrently interspersed with tales, whose plots accentuate sacrifice, generosity, good deeds. At this rhythm, they arrive in São Paulo, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Paraná, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Alagoas, Ceará, Sergipe, Maranhão, Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Norte, Amazonas, Acre, Goiás, and in Mato Grosso. At each stop, an exemplary tale is told, a story. In the stories, the History of Brazil is concomitantly narrated; a peculiar type of Brazilian History told to children. The historical figures, the wars, the historical facts, the monuments dedicated to the heroes of the country are, so to speak, the structuring axes of the narrative, of the symbolic and patriotic journey around Brazil undertaken by the reader.

The tale entitled “Uma pergunta” (A question) consists of an interesting illustration of how to build the narratives intertwined by the author. Having traveled the country from north to south, the reader accompanies in this part two children facing the challenge of writing a composition of a historical nature, which addressed the event starring the most outstanding character in the History of Brazil. Children oscillate before the countless facts that they consider memorable: the discovery of Brazil and the discoverers; the selflessness of the Jesuits fighting anthropophagy, civilizing, dying for their ideas; the bravery of Bishop Dom Pero Fernandes Sardinha, devoured by the Caetés Indians; Father Antonio Vieira and his sermons or his reports on politics, administration, diplomacy; the episode of the proclamation of the Republic, with an emphasis on the role of Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca and the 15th of November 1889, when, at last, the Republic was established and so, in the narrator's view, “[...] the true government of all the people ”(Almeida, 1911, p. 157). Finally, the children turn to the maternal advice, which guides them towards the dissertation about the deeds of honor and peace as opposed to the violence of wars. As good students above all and guided by modern maternal pedagogy, they chose to discuss the pacifist alternative.

As for the closing of Historias da nossa terra, the reader goes through, this time, a long story, organized in ten parts. It does not take place in a specific Brazilian state. Within the scope of the project, it is important to understand it as the synthesis of the unity of States, the representation of the national territory. It tells the story of O Gigante Brasilião (The Giant Brasilião). Julia Lopes de Almeida had already published these short story sections in the newspaper O Paiz, as can be read in the editions of 27 and 28 February 1897 (O Paiz, 1897a, 1897b). O Gigante Brasilião was later integrated with the other texts that comprise Historias da nossa terra, which came to light in 1907, when it was published by the bookshop and publisher Francisco Alves.

In the story, Aunt Michaela slept. However, she was awakened by a mysterious voice. At the door of her house is a newborn baby on whose neck it is written: “My name is Vasco and I am the son of the Giant Brasilião”. In that region, a legend ran about the existence of a giant called Giant Brasilião. According to the legend, the giant was the owner of all the land. At the age of 14, with the death of Aunt Michaela, Vasco sets out searching for the giant, who was said to be his father.

One cannot fail to point out the choice of the name of the protagonist Vasco. It has a symbolic meaning in the scope of the work's project, since it refers to Vasco da Gama, a historical figure associated with the European maritime expansion, the great navigations and the expansion of commercial activities by European colonists between the 15th and 17th centuries. According to this interpretative key, it is possible to understand Vasco’s efforts in departing to search the Giant Brasilião: Vasco, the pioneer of unknown lands. Once again, the author mobilizes the narrative model of the bildungsroman, aiming to successfully construct the narrative and the character. Note that, during the trip to meet the giant, the boy faces wild animals: alligators, snakes, jaguars. He listens to the most different stories about the existence of Brasilião. He faces deprivation. However, he overcomes all adversities along his difficult journey. Upon arriving at a house in a deserted village, where 20 boys read in front of a master, "[...] the one who knows everything" (Almeida, 1911, p. 218), he is informed that it is a legend: the legend of the “Giant Brasilião, the name given by the people to our country” (Almeida, 1911, p. 219), as shown in figure 3, below. And in the Master’s words

The Giant Brasilião is all this: those huge mountains are his back; those tallest trees are his muscles; those rivers and seas are his most fertile veins; this aroma of sap, his breath, and the hard rocks, his bones; and the starry nights are his dreams! (Almeida, 1911, p.219-220).

Final remarks

The Gigante Brasilião, therefore, constitutes a fundamental part of the architecture of the work to shape the civic and patriotic project, woven in the pages of Historias da nossa terra. It was the grandiose vision provided by the myth of origin of the Brazilian nation rediscovered by Vasco: the Brazilian territory, with borders, seas, mountains, everything well delimited, a synthesis of the national identity. To this vision was added the function of teaching the reader of Historias da nossa terra the primer of nationalism, by means of the exaltation of flora-“[...] trees as tall as muscles [...]”-and of Geography, "[...] rivers and seas like veins [...]"; “[...] huge mountains like back [...]”; “[...] rocks as hard as bones” (Almeida, 1911, p. 219-220). Through the prideful rhetoric, it was expected, therefore, to consolidate a coherent set of beliefs and traditions around what should be considered the rediscovered nation, privileging heroes, lands, and episodes in a consecration work that responded to the needs of that period, the first decades of republican Brazil.

Julia Lopes de Almeida stood out in the historiography of the Brazilian female press for her diverse performance in literate culture, notably in the first decades of the republican Brazil. She wrote articles, short stories, novels, plays, chronicles and school reading books. Within the scope of her intellectual project, Historias da nossa terra properly illustrates the writer's investment in education in the area of Letters. Within the book, on the one had she was able to mobilize the civic pantheons of the Brazilian Republic through symbols such as the national flag and the mother tongue, but on the other hand she gave children readers a journey around Brazil in search for their republican identity through composition exercises, exemplary stories and letters. As the historian Curvello de Mendonça emphasized, in his critical column on the reception of the textbook published in O Paiz, in 1907, the genres that comprised the book were written in a “[...] serene and strong way, capable of making a name for a writer” (column 1). In this sense, it is necessary to underline that the writer integrated the writing project of recognition of Brazil through school reading books, such as Coração and Através do Brasil, which, as studies in the history of education and cultural history have shown, contributed to the civic and patriotic construction of the Brazilian nation, notably mobilized by the circulation of printed material.

REFERENCES

Almeida, J. L. (1911). Historias da nossa terra (6a ed. rev. e aum.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Amicis, E. (1954). Coração (46a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Livraria Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Anderson, B. (2008). Comunidades imaginadas: reflexões sobre a origem e a difusão do nacionalismo. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro. (2018, 23 de novembro). Coleção Prefeitura do Distrito Federal. Série Instrução Pública. Códice 33.4.20, p. 58. [ Links ]

Artur Azevedo: biografia. (2020). Recuperado de: http://www.academia.org.br/acadêmicos/artur-azevedo/biografia [ Links ]

Batista, A. A. G., Galvão, A. M. O., & Klinke, K. (2002). Livros escolares de leitura: uma morfologia (1896-1956). Revista Brasileira de Educação, 20, 2-47. [ Links ]

Barbosa, M. (2010). História cultural da imprensa no Brasil - 1800-1900. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Mauad X. [ Links ]

Bastos, M. H. C. (2008). A educação do caráter nacional: leituras de formação. Educação e Filosofia, 12(23), 31-50 [ Links ]

Bilac, O., & Bomfim, M. (2000). Através do Brasil (Marisa Lajolo, org.). São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras . [ Links ]

Bilac, O., & Bomfim, M. (1931). Atravez do Brazil: livro de leitura para o curso médio das escolas primarias (22a ed. rev.) Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Francisco Alves. [ Links ]

Blake, S. (1883-1902). Diccionario bibliographico brazileiro (Vol. 6). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typ. Nacional. [ Links ]

Botelho, A. (2002). Aprendizado do Brasil: a nação em busca dos seus portadores sociais. Campinas, SP: Editora da Unicamp. [ Links ]

Bragança, A. (2000). A política editorial de Francisco Alves e a profissionalização do escritor no Brasil. In M. Abreu (Org.), Leitura, história e história da leitura (p. 451-476). Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Carvalho, J. M. (1990). A formação das almas: o imaginário da república no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras . [ Links ]

Chervel, A. (1998). História das disciplinas escolares: reflexões sobre um campo de pesquisa. Teoria & Educação, 1(2), 177-229. [ Links ]

Choppin, A. (2004). História dos livros e das edições didáticas: sobre o estado da arte. Educação e Pesquisa, 30(3), 549-566. [ Links ]

Choppin, A. (2002). O historiador e o livro escolar. História da Educação, 6(11), 5-24. [ Links ]

Decreto Imperial nº 10.202, de 9 de março de 1889. Recuperado de: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1824-1899/decreto-10202-9-marco-1889-542443-publicacaooriginal-51422-pe.html [ Links ]

Escolano, A. (2012). El manual como texto. Pro-posições, 23(3), 33-50. [ Links ]

Forquin, J. C. (1992). Saberes escolares, imperativos didáticos e dinâmicas sociais. Teoria & Educação , 5, 28-49 [ Links ]

Gomes, A. C. (2016). Aventuras e desventuras de uma autora e editora portuguesa: Ana de Castro Osório e suas viagens ao Brasil. In A. C. Gomes & P. S. Hansen (Orgs.), Intelectuais mediadores: práticas culturais e ação política (p. 92-120). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira, [ Links ]

Guimarães, M. L. S. (2011). Historiografia e nação no Brasil (1838-1857). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: EdUERJ. [ Links ]

Hallewel, L. (2012). O livro no Brasil: sua história. São Paulo, SP: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Instituto Benjamin Constant. (2020). Recuperado de: http://www. ibc.gov.br [ Links ]

Julia, D. (2001). A cultura escolar como objeto histórico. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação , 1, 9-44. [ Links ]

Lei nº 839, de 26 de setembro de 1857. Recuperado de: http://helb.org.br [ Links ]

Magaldi, A. M. M. (2007). Lições de casa: discursos pedagógicos destinados à família no Brasil. Belo Horizonte, MG: Argvmentvm. [ Links ]

Mendonça, L. (1897). As três Julias. Almanaque Brasileiro, 246-249. [ Links ]

Muzart, Z. L. (Org.). (2015). Escritoras brasileiras do século XIX, I e II. Florianópolis, SC: Editora Mulheres. [ Links ]

O Paiz. (1897, 27 de fevereiro). Edição 04530, p. 2. [ Links ]

O Paiz. (1897, 28 de fevereiro). Edição 04531, p. 2. [ Links ]

O Paiz. (1904, 22 de julho). Edição 07227(1), p. 1. [ Links ]

O Paiz. (1907, 12 de junho). Edição 08287(1), p. 2. [ Links ]

Pimenta, H. H., &Somoza, M. (2012). Apresentação do dossiê Manuais escolares: múltiplas facetas de um objeto cultural. In Dossiê manuais escolares: múltiplas facetas de um objeto cultural. Pro-posições , 23(3). [ Links ]

Porto, A., Sanglard, G., Fonseca, M. R. F., & Costa, R. G. R. (2008). História da saúde no Rio de Janeiro: instituições e patrimônio arquitetônico. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora Fiocruz. [ Links ]

Schumaher, S., & Brasil, E. V. (Orgs.). (2000). Dicionário mulheres do Brasil: de 1.500 até a atualidade. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Jorge Zahar. [ Links ]

Silva, M. C., & Pinto, M. S. (2018). Discursos em disputa sobre a Bibliotheca Infantil em O Paiz (1894-1899). Revista Educação em Questão, 56(47), 221-243. [ Links ]

Silva, V. M. A. (1979). Teoria da literatura. Lisboa, PT: Almedina. [ Links ]

Sirinelli, J. F. (2003). Os intelectuais. In R. Rémond. Por uma história política (p. 231-269). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: FGV. [ Links ]

Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação [SBHE]. (2020). Recuperado de: http://www.sbhe.org.br [ Links ]

Stasio, A., Faedrich, A., & Ribeiro, M. V. (Orgs.). (2016). Dois dedos de prosa: o cotidiano carioca por Júlia Lopes de Almeida (Cadernos da Biblioteca Nacional). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: FBN. [ Links ]

Vidal, D. G. (2005). Culturas escolares: estudo sobre práticas de leitura e escrita na escola pública primária (Brasil e França, final do século XIX). Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Vidal, D. G. (2004). Julia Lopes de Almeida e a educação brasileira no fim do século XIX: um estudo sobre o livro escolar Contos Infantis. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 17(001), 29-45. [ Links ]

Viñao Frago, A. (1995). Historia de la educación e historia cultural. Revista Brasileira de Educação , 1(0), 63-82. [ Links ]

29Check out the mapping, among other studies, in Pimenta and Somoza (2012).

30The Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação (SBHE, the Brazilian Society for the History of Education) was created in 1999 and brings together Brazilian professors and researchers who carry out teaching and research activities in the area. The Brazilian Congresses on History of Education have been held biannually since 2000 and, in 2019, the 10th edition was held. The comparison was made from the works published in the Annals of Congress, which is available on the SBHE’s page (2020).

31In this study we used the 6th edition, revised and updated in 1911, published by Livraria Editores Francisco Alves & Cia; Aillaud Alves & Cia. (Paris and Lisbon). All quotes, therefore, are taken from this edition.

32O Paiz, a newspaper from Rio de Janeiro, was founded on October 1, 1884 by João José Reis Júnior - Count São Salvador de Matosinhos. Calling itself an 'independent, political, literary and informative newspaper, O Paiz emphasized its autonomy in relation to specific groups, an idea that, in the opinion of its editors, would allow its impartiality. It was also defined as a republican newspaper, standing out, in the last years of the Monarchy, in the abolitionist campaigns. Cf: Silva and Pinto (2018) and Barbosa (2010).

33Julia Valentim da Silveira Lopes de Almeida (Rio de Janeiro, 1862-1934), in 1911, as read on the page after the fake cover page of the work consulted for the purposes of this study (6th ed. revised and updated in 1911), had already published Traços e iluminuras (Strokes and illuminations, in 1887) (short stories); A família Medeiros (The Medeiros family, in 1892) (romance of customs); Memórias de Marta (Martha's Memories, in 1899) (narratives and stories); A viúva Simões (The Simões widow, in 1897) (novel); Livro das noivas (Book of brides, in 1896) (practical notions of domestic life); Ânsia eterna (Eternal longing, in 1903) (short stories); Livro das donas e donzelas (Mistresses and Maidens Book, in 1906) (chronicles); A falência (Bankruptcy, in 1902) (romance). Collaborative works: Contos infantis (Children's stories, in 1886), prose tales and verses adopted for use in primary schools in the Federal District, and in the States of São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná and Pará, with their sister Adelina Lopes Vieira.

34A chronicle published in the column “Dois dedos de prosa” (A little bit of prose) of the newspaper O Paiz, on November 15, 1910, in which the author discusses the new installations and functioning of the National Library. The researchers selected 40 chronicles published in the period between 1908 and 1912.

35Also check the study developed by Magaldi (2007), in which the author examines the subject in detail.

36In the article 'As Três Julias', the academic Lucio de Mendonça comments on the production of three writers of the period: Julia Lopes de Almeida, Francisca Julia da Silva, and Julia Cortines. At the end of the text, he regrets that, when the Academia de Letras was founded in 1897, although Valentim Magalhães, Filinto Almeida and himself were in favor of admitting women to the institution, their idea was opposed by a majority group at the institution. Check it out in Mendonça (1897).

37In this regard, check out the Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (General Archive of the Rio de Janeiro City, 2018).

38The firm had grown from the mid-1890s and appears to have held almost the monopoly of the textbook printing in Brazil. In part, this monopoly is due to the practice of long runs, which could lower prices, as well as the acquisition of rival firms. It was the editor of Francisco Vianna, João Ribeiro, Joaquim Maria de Lacerda, Júlio Ribeiro, Maximino Maciel, Tomás Galhardo, Ramiz Galvão, Afrânio Peixoto, Júlia Lopes de Almeida, among others. Check out notawell (2012).

39Artur Azevedo (Artur Nabantino Gonçalves de Azevedo) (1855-1908) collaborated, together with his brother Aluísio de Azevedo, with the founding group of the Academia Brasileira de Letras, creating the chair n. 29, whose patron is Martins Pena. He worked as a teacher, but it was as a chronicler and theatrologist that he achieved prominence in the field of letters (Artur Azevedo: biography, 2020).

40In the study dedicated to the Portuguese intellectual Ana de Castro Osório, Angela de Castro Gomes establishes this concept to refer to the author's intellectual project in the production of children's books in Portugal and Brazil. We noticed similarities between the projects of both intellectuals, which motivated us to adopt the concept regarding the case of Julia Lopes de Almeida. Check out Gomes (2016).

41On school culture, we rely mainly on Julia (2001), Chervel (1998), Forquin (1992) and Vinão Frago (1995).

42 Botelho (2002) indicates that the book had successive editions, 66, and was used through more than 50 years in Brazilian schools. In this study, we used the 22nd revised edition, 1931 (Bilac & Bonfim, 1931).

43According to Bastos (2008), the book had wide circulation, being translated into 25 languages, besides adaptations for Italian television and radio.

44Manoel Curvello de Mendonça (1870-1914), historian, whose reference work is Sergipe republican: estudo crítico e histórico (Republican Sergipe: critical and historical study) on science and politics debates. Cf: Blake (1883-1902).

45Check out the study by Vidal (2004), in which the author analyzes the book. In addition to this exam, Vidal (2005) develops a study in which she establishes approximations and distinctions between Short stories for children and La comédie enfantine, by Luiz Ratisbone.

46Check out the Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (2018).

47Check out, among other studies, Carvalho (1990), in which the historian shows how monuments erected in public squares, flags and national anthems help to decipher the mythology and symbolism of a political system.

48Check out the study by Guimarães (2011). The exam shows how history writing participated in the process of affirming the national state and nation-building. In these terms, historical knowledge is denaturalized and instituted as a national construction.

49On March 9, 1889, the Imperial Decree No. 10.202 was signed creating the Imperial Military College of the Court and approving its regulations (Imperial Decree No. 10.2020 of 1889).

50On September 17, 1854, it was opened on Rua do Lazareto, n. 3, in the neighborhood of Gamboa, Rio de Janeiro, the Imperial Institute for the Blind Children. In 1891, it moved to the neoclassical style building located on the old Praia da Saudade, now Praia Vermelha and changed its name to Instituto Benjamin Constant. Check out Instituto Benjamin Constant, 2020.

51The Imperial Institute for the Deaf and Mute was created by Law No. 839 of September 26, 1857 and renamed the National Institute for the Education of the Deaf - INES as of the advent of the Republic. Cf: (Lei nº 839, 1857).

52Instituto Pasteur, created in 1888 in Rio de Janeiro, was responsible for the manufacture of anti-rabies serum. See Porto, Sanglard, Fonseca and Costa (2008).

53A similar structure can be seen in O Thesouro, Aventuras de Rosinha, O preto velho, Amor da pátria, Depois da Batalha, Coragem, A fábrica, and Antes de morrer de fome. All citations refer to the 1911 edition used in this study.

54Os anos de aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister's, a novel by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is considered the starting point of the bildungsroman. Check out Silva (1979).

55Check also in the preface written by Marisa Lajolo, in which she discusses this type of structure of the novel in Através do Brasil, published by Olavo Bilac and Manoel Bomfim, 1910 (Bilac & Bomfim, 2000).

56Note that The golden bell (children's story) was first published separately in O Paiz and only later, in 1907, would compose the book Histories of our country. Check: in O Paiz (1904).

How to cite this article: Silva, M. C. “Histories of our country”: on the civic project of construction of the Brazilian nation through print. (2020). Brazilian Journal of History of Education, 20. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v20.2020.e128 This paper is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC -BY 4).

1Conferir o mapeamento, entre outros estudos, em Pimenta e Somoza (2012).

2A Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação (SBHE) foi criada em 1999 e reúne professores e pesquisadores brasileiros que desenvolvem atividades de ensino e de pesquisa na área. Os Congressos Brasileiros de História da Educação ocorrem bianualmente desde 2000 e se encontra, em 2019, na Xª edição. O cotejo foi realizado a partir dos trabalhos publicados nos Anais do Congresso e disponível na página da Sociedade Brasileira de História da Educação [SBHE] (2020).

3Neste estudo utilizamos a 6ª edição, revista e atualizada, de 1911, publicada pela Livraria Editores Francisco Alves & Cia; Aillaud Alves & Cia. (Paris e Lisboa). Todas as citações, portanto, são extraídas dessa edição.

4O Paiz, jornal carioca, foi fundado em 1º de outubro de 1884 por João José Reis Júnior - Conde São Salvador de Matosinhos. Intitulando-se um jornal ‘independente, político, literário e noticioso’, O Paiz enfatizava sua autonomia em relação a grupos específicos, ideário que, na visão dos articulistas, permitiria sua imparcialidade. Definia-se, ainda, como jornal republicano, destacando-se, nos últimos anos da Monarquia, nas campanhas abolicionistas. Cf: Silva e Pinto (2018) e Barbosa (2010).

5 Julia Valentim da Silveira Lopes de Almeida (Rio de Janeiro, 1862-1934), em 1911, como se lê na folha seguinte à falsa folha de rosto da obra consultada para fins deste estudo (6 a ed. revista e atualizada de 1911), já havia publicado Traços e iluminuras (1887) (contos); A família Medeiros (1892) (romance de costumes); Memorias de Martha (1899) (narrativas e contos); A viúva Simões (1897) (romance); Livro das noivas (1896)(noções práticas da vida doméstica); Ansia eterna (1903) (contos); Livro das donas e donzelas (1906) (crônicas); A falência (1902) (romance). De colaboração: Contos infantis (1886) contos em prosa e versos adotados para uso das escolas primárias do Distrito Federal, e dos Estados de São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, Paraná e Pará, com sua irmã Adelina Lopes Vieira.

6Trata-se de uma crônica, veiculada no jornal O Paiz, em 15 de novembro de 1910, na qual a autora discute as novas instalações e funcionamento da Biblioteca Nacional na coluna ‘Dois dedos de prosa’. Os pesquisadores selecionaram 40 crônicas publicadas no período entre 1908 a 1912.

7Conferir também a esse respeito o estudo desenvolvido por Magaldi (2007) no qual a autora examina o assunto em detalhes.

8Trata-se do artigo ‘As três Julias’, no qual o acadêmico Lucio de Mendonça comenta a produção de três escritoras do período: Julia Lopes de Almeida, Francisca Julia da Silva e Julia Cortines. Ao final do texto, ele lamenta que, na fundação da Academia de Letras em 1897, Valentim Magalhães, Filinto Almeida e ele próprio fossem favoráveis à admissão de mulheres na instituição. No entanto, a ideia fora combatida pelo grupo majoritário da instituição. Conferir em Mendonça (1897).

9Conferir a este respeito: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (2018).

10A firma havia crescido a partir de meados de 1890 e parece ter detido quase o monopólio do campo do livro didático no Brasil. Em parte, esse monopólio deve-se à prática de grandes tiragens, que poderia baratear os preços, assim como a aquisição de firmas rivais. Foi editor de Francisco Vianna, João Ribeiro, Joaquim Maria de Lacerda, Júlio Ribeiro, Maximino Maciel, Tomás Galhardo, Ramiz Galvão, Afrânio Peixoto, Júlia Lopes de Almeida, entre outros. Conferir: Hallewell (2012).

11Artur Azevedo (Artur Nabantino Gonçalves de Azevedo), (1855-1908) colaborou ao lado do irmão Aluísio de Azevedo com o grupo fundador da Academia Brasileira de Letras, criando a cadeira n. 29, que tem como patrono Martins Pena. Exerceu o magistério, mas foi como cronista e teatrólogo que logrou destaque no campo das letras (Artur Azevedo: biografia, 2020).

12No estudo dedicado a intelectual portuguesa Ana de Castro Osório, Angela de Castro Gomes estabelece esse conceito para se referir ao projeto intelectual da autora na produção de livros infantis em Portugal e no Brasil. Percebemos semelhanças entre os projetos de ambas as intelectuais, o que nos motivou a adotar o conceito para o caso de Julia Lopes de Almeida. Conferir em Gomes (2016).

13Sobre cultura escolar, apoiamo-nos, principalmente, em Julia (2001), Chervel (1998), Forquin (1992) e Vinão Frago (1995).

14 Botelho (2002) indica que o livro contou com sucessivas edições, 66, e foi utilizado por mais de 50anos nas escolas brasileiras. Neste estudo, utilizamos a 22ª edição revista de 1931 (Bilac & Bonfim, 1931).

15Conforme os estudos de Bastos (2008), o livro teve ampla circulação, registrando-se traduções em 25 idiomas, adaptações para a televisão e o rádio italianos.

16Manoel Curvello de Mendonça (1870-1914), historiador, cujo trabalho de referência é Sergipe republicano: estudo crítico e histórico sobre debates de ciência e política. Cf: Blake (1883-1902).

17Conferir a esse respeito estudo desenvolvido por Vidal (2004), no qual a autora analisa o livro. Além desse exame, Vidal (2005) desenvolve estudo no qual estabelece aproximações e distinções entre Contos infantis e La comédie enfantine, de autoria de Luiz Ratisbone.

18Conferir a esse respeito: Arquivo Geral da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (2018).

19Conferir, entre outros estudos, Carvalho (1990). No estudo, o historiador mostra como monumentos erguidos em praça pública, bandeiras e hinos nacionais auxiliam a decifrar a mitologia e simbologia de um sistema político.

20Conferir a esse respeito, entre outros, o estudo de Guimarães (2011). O exame mostra como a escrita da história participou do processo de afirmação do Estado nacional e de construção da nação. Nesses termos o conhecimento histórico é desnaturalizado e instituído como construção nacional.

21Em 09 de março de 1889 foi assinado o Decreto Imperial nº 10. 202, criando o Imperial Colégio Militar da Corte e aprovando o seu regulamento (Decreto Imperial n. 10.2020 de 1889).

22No dia 17 de setembro de 1854 foi inaugurado na rua do Lazareto, n. 3, do bairro da Gamboa, Rio de Janeiro o Imperial Instituto dos Meninos Cegos. Em 1891, mudou para o prédio de estilo neoclássico localizado na antiga Praia da Saudade, hoje Praia Vermelha e mudou o nome para Instituto Benjamin Constant. Conferir: (Instituto Benjamin Constant, 2020).

23O Imperial Instituto de Surdos-Mudos foi criado pela lei nº 839 de 26 de setembro de 1857 e renomeado Instituto Nacional de Educação dos Surdos - INES a partir do advento da República. Cf: (Lei nº 839, 1857).

24Instituto Pasteur, criado em 1888 no Rio de Janeiro, tinha como função a fabricação do soro antirrábico. Cf. em Porto, Sanglard, Fonseca e Costa (2008).

25Estrutura semelhante pode ser observada em O Thesouro, Aventuras de Rosinha, O preto velho, Amor da pátria, Depois da Batalha, Coragem, A fabrica e Antes morrer de fome. Todas as citações referem-se à edição de 1911 utilizada neste estudo.

26Os anos de aprendizado de Wilhelm Meister, romance do escritor Johann Wolfgang von Goethe é considerado o marco inicial do Bildungsroman. Conferir em Silva (1979).

27Conferir também no prefácio escrito por Marisa Lajolo, no qual discorre sobre esse tipo de estrutura do romance em Através do Brasil, lançado por Olavo Bilac e Manoel Bomfim em 1910 (Bilac & Bomfim, 2000).

28Note-se que O sino de ouro (conto para crianças) foi primeiro publicado separadamente em O Paiz e só mais tarde, em 1907, comporia o livro Historias da nossa terra. Conferir: em O Paiz (1904).

Received: June 15, 2020; Accepted: June 26, 2020

texto em

texto em