Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.21 Maringá 2021 Epub 17-Nov-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e141

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

The Illustrated Album of the County of Rio Preto (1927-1929): showroom and epiphany of education in the São Paulo State

1Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brasil.

The objective of the present paper was to examine the representations of education disseminated in the extension of 479 texts and 1935 iconographies that integrate the 1093 pages of the Álbum Ilustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929). For that, based on the principles of Cultural History and Discourse Analysis, we carried out an examination of the social process of production of this artifact and the materiality of the spellings of educational nature that compose it. Thus, an effort of verbal-visual exaltation of popular and official instruction as sign of progress was verified, in an enunciative diligence that fixed the typographical object investigated as support and, at one time, as the incarnation of the civilizing and educational projects that their artificers sought to participate in.

Keywords: history of education; press; imagetic culture; public school.

No presente artigo, objetivou-se perscrutar as representações de educação difundidas na extensão dos 479 textos e das 1.935 iconografias que integram as 1.093 laudas do Álbum Ilustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929). Para tanto, com base nos princípios da História Cultural e da Análise do Discurso, examinou-se o processo social de produção deste artefato e a materialidade das grafias de cunho educacional que o compõem. Assim, averiguou-se um esforço de exaltação verbo-visual da instrução popular e oficial como indício de progresso, em uma diligência enunciativa que fixou o objeto tipográfico investigado como suporte e, a um só tempo, como a encarnação dos projetos civilizatórios e educativos que seus artífices buscaram participar.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; imprensa; cultura imagética; escola pública

En este artículo, el objetivo era examinar las representaciones de la educación difundidas en la extensión de los 479 textos yde las 1935 iconografías que integran las 1093 páginas del Álbum Ilustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929). Con este fin, basado em los principios de la Historia Cultural y el Análisis del Discurso, se examinó el proceso social de producción de este artefacto y la materialidad de grafías de carácter educativo que lo componen. Tan, se encontró un esfuerzo de exaltación verbo-visual de la instrucción popular y oficial como síntoma de progreso, en una diligencia enunciativa que fijó el objeto tipográfico investigado como soporte y, al mismo tiempo, como la encarnación de los proyectos civilizatorios y educativos que sus autores buscaron participar.

Palabras clave: historia de la educación; prensa; cultura de imágenes; escuela pública

Introduction

Nunes and Carvalho (2005) as they analyze the research standings on History of Education in Brazil, listed Cultural History, specially the one based on Roger Chartier's (2002) theoretical hypothesis, as one of the main trends that provoked renovation in the historiographical practice of this field. According to the authors, the changes that happened on the sources, objects, theories and methodologies of historiography, both general and educational, brushed the visibility of the historicity of each of these axes, thus enabling explorations that travel from the signifier to the signified, from vehicle to message, and from this to social groups that appropriated its use. Considering this, corroborating with Certeau's (2011) preconizations, an interpretative mobilization towards comprehending possibilities and limitations takes place, one that is about the practices of sociocultural models have in their own enunciative process.

According to Prost (2014), such emphasis on the historicity coincided with and was maximized by the transformations occurring in the interior of Linguistics, where structuralist paradigms began to be questioned by scholars that considered a whole social fabric that preceded, materialized and exceed the signical marks of the utterance. Based on Orlandi's (2003,2005) and Fiorin's (2006, 2008) inquiries, it is evident that the exponents of such analytical resignification are the philosophers Michel Pêcheux (2006, 2009) and Mikhail Bakhtin (2006, 2011), that, despite their particularities of thought, commungated the idea of a primacy of the dialogicity of the utterance. Thus, for these two aforementioned authors, each utterance is just a dimension of a discourse thread, since its production conditions dialogue with other discourses, either pre-existent or conjectured from such utterance, and the discourses, on their turn, are constituted by a sociocultural context.

Thus, the investigations that are oriented to this theoretical framework alignment, within the scope of History of Education, embrace the educational aspect beyond its correspondences with knowledge and the space where it is formally carried out, as these are considered, in this sense, as an unfolding of a certain model of society and culture. As indicators of these panoramas, are the diligences of Campos (2015, 2017), on which the education is apprehended under formal and informal domains, through examining the practices of the illustrated press in the state of Sao Paulo, from the first half of the twentieth century, especially of those that were incarnated into illustrated albums. These typographic works, as stated by Carvalho and Lima (2008), are characterized by having a narrative engined by photographic visual texts, whose iconographies of cities and urban themes took on, among other objectives, a pedagogical role of familiarizing with the urban social order intended by its artifices.

In this way, basing on the conceptual apport of cultural history and poststructuralist discourse analysis, means considering that the source-objects of evaluation in history of education are elements that composed an enunciative scenario of a social group, at a time and space relatively delimited. In parallel, it is reputed that their own materiality contains other items of such scene, which are traced by the most diverse spellings, constituting as one of the indissoluble responsible for the provided effects of meaning, at the time of their conceptions, for the whole linguistic concreteness. Therefore, the inevitable suggestion is that understanding the utterances of source-objects leans on the perception of the social culture of its itineraries of production, circulation and reception, as well as on the tangible existences and its purposes, both individual and collective, subjective and objective, clarifying power relations that girded each step of their execution.

Before such context of proposing different scientific and historiographic gazes to multiple educational and educative manifestations, the present paper was outlined and structured having, as its source-object, the Album Ilustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929)7. This analytical definition was based on the considerations that Campos (2015) wove about it, one that enables verifying the force with which the palpable dimension of this publication exerted on the social imaginary of groups of the northwest region of the state of São Paulo, being connected to a civilizing project that claimed for scholarization. Hence, as we ponder about the inquiries of Souza (2000) and Abdala (2013), it is assumed that the focus on the listed artefact contributes to the widen the comprehension of a peculiar era in Brazil, on which certain erudite circles catalogued photography and education as, respectively, an identifier and a cause of society's progress.

For this reason, the theme of the current textual production focused on representations of education transmitted through typographic work aiming at, as they are quivered on their conjecture and tangibility, that the understanding was led to the social function of their support. Consequently, the apprehension started from the Album as a string of discourses that circulated at the time of its making, on which enunciative strategies chosen by their organizers were articulated for the expectations of correspondences desired for cultural devices and to the citizenship identities themselves. Due to this discernment, exposing the results of this research will necessarily go through a historical-material enunciative order, that is, from the external to the internal, from context to utterance, which returns to the external, returns to its discursive scenario, without closing, nonetheless, the respective enunciative chain.

The discursivity of the Brazilian imagery press

According to Maia (2007) and Martins (2013), the beginnings of the imagery press in Brazil, despite being contiguously woven to the advent moment of press in this country, still in monarchy times, were planned in an environment of dense vias of informational dissemination, spoken or written, already existing in society. As claimed by Mendes and Moreira (2007) and Cohen (2013), the onset of such subdivision of press is defined and marked by the production and circulation of publications of lithographed caricatures, that, not skewing from political issues, were projected to reach the public, erudite or not, through humor and visual fruition. For such understanding, the dawn of the Brazilian illustrated press corresponds to the time in which the linguistic discourses of typographic objects began to be designed with and through the notable presence of lithographic resources, which exercised, on their relevant utterance, their own narrative task, and not an ornamentation one.

In contrast, Ramos (2009) associates the exordium of the illustrated press of Brazil to the use, routinely described as decorative, of tiny xylographs, rudimentary and without authorship signatures, on the headings of the periodic that preceded, in Brazil, the publications that expressed the possibilities of lithography. This researcher demonstrates, through studies carried out about printed image of the first half of the nineteenth century, that the xylographs, although their meager technical refinement, did not only satisfy the adornment of the channel they were reproduced and diffused in, since they fulfilled, alongside similar words, the ideological program of such publishing support. Thus, for this perspective, the emergence of the Brazilian Illustrated press coincides with the period in which the meaning of the journalistic discourse began to traced by and through the relation, dialogic and contradictory, between reader, reading, place, time, linguistic and visual codes, sign, and typographic forms listed by authors and decided by editors.

Considering this, the ponderations that Ramos (2009) establishes about the imagery press, especially when it comes to the message coming from the indissoluble union of visual-ornamental elements such as the written text, converge with what Brait (2011, 2013) denominates verbal-visuality. According to this author's thoughts, the verbal-visual dimension of an utterance characterizes itself as a plan of material expression structured on the syncretism of two languages, the verbal and visual, which connected and chained in the creation or editing of a publication, become the constitutive agents for the production of the discursive meaning. Thus, the conciliation of these thesis defended by the last two aforementioned authors indicate that the verbal-visuality is the defining aspect of the illustrated press, whose distinctive arrangements of both written and visual texts interfere in the composition, theme and style of typographic works where they are being materialized.

Among the press products that only exist in the illustrated form, are the city themed albums, that come from, as Pereira (2010) has pointed out, the realization of political-commercial events, on which, as achieved civilizing advances are presented, investments from various species were glimpsed, in many sectors. In Brazil, according to Barbuy (1996), the production of objects to circulate in these meetings preceded and succeeded the realization of these, and, the illustrated albums, were in charge of corporifying whatever could not be present, such as sanitation improvements, as well as, posteriorly, to storage what happened in such events. Regarding the making of these imagery works, a tendency to correspond to spatial growth was followed, in which, first, albums of municipalities, or of a group of small districts, and, later, of federal states were built, until finally reaching the elaboration of a national album.

Thus, the path of facts that led these imagery artefacts to be made, as a collectivity, denote a communicative and social functioning of its discourses, centered around the dialogue that they maintain between each other and, also, as other voices that preceded and that, because and for them, were conjectures to succeed them. This notion of dialogic beginning as a particular way of composing utterances, one where the institution and real operation of language anchor on exteriority, whose meaning results from the relation with its interlocutors, is addressed by Pêcheux (2006, 2009), by the interdiscourse graphy, and on Bakhtin (2006, 2011), through dialogism. As a result, the illustrated albums are shaped as concrete discourses, each of them being the link of a multifaceted enunciative chain, in which, through the materiality of such, the transmission and reciprocal construction of meaning effects occurs between the subjects who systematize them and assign them to something, or someone, and their specific recipients

Therefore, its editorial configuration, which Carvalho and Lima (2008) distinguished by its hardcover coating and its plot with numerous urban photographs embodied in coated paper, constitutes a vestige of the dialogicity itself that underlies the relevant enunciative sphere. This evidence is confirmed, when comparing the exams of these historians with those of Park (1999) and Oliveira (2001), because, together, they signal that the intrinsic palpable sumptuousness of the illustrated albums was used, by the groups that led their manufacture, as a premise of the eminence that these forms had before the already propagated almanacs. Considering this, in the light of Chartier's (2014) postulations, what these elites projected in support of imagery typographic objects was consistent with a civilized ethos model of actor and action, whose characters amalgamate in the appearance of the elect social communication channel.

Thus, it is not innocuous to verify that the two referred theoretical tendencies about the origins of the imagery press share the perspective that this typographic segment gained centrality in the republican bosom, especially in the 1920s, and in the plagues of the State of São Paulo. From a temporal point of view, considering Cohen's reflections (2013), the explanation for the profusion of Brazilian illustrated devices, in the decade ending in 1929, finds support in the improvement of typography devices, in the increase of the publishing market, and in the diverse use that intellectuals made of such. In its turn, the protagonism of that federative space, based on what Campos (2015) emphasized, can be elucidated by the proposals outlined by local groups of greater visibility, which were aimed at making the countryside region of São Paulo a national and international reference for civilization and modernity.

In this same sense, alluding to Sodré (2004), it is unraveled that the deliberation by the artefacts of this subdivision of the printed communication was anchored in political pretexts, considering that it was convenient, to the structuring and legitimization of the republican ideals and discourses in vogue in Brazil at the time; the social use of technical news. Supplementary in character, there was a technical-commercial bias, which, according to Martins (2013), underpinned and surpassed this type of press, since, in this context, the perpetuation of the journalistic sector was linked to the improvement of typographic devices, as well as the resulting pieces of them, which resulted from and fostered new market relations. Finally, the intentional choice of materials for publishing followed, according to the suggested by Mason (2003), an illuminist educational aspiration, since the accessibility to the syncretic language of the written texts and images that those published, empowered the autonomy of the subject on his or her knowledge.

Regarding the illustrated albums, singular representatives of the diluted press category, the political, commercial and educational axes were brought together in the visibility projects of the national and international exhibitions that originated them, which Kuhlmann Jr. (2001) called 'great didactic parties'. For this author, these ceremonies were marked by an inflection, on the discursive level, that education, especially school education, was a privileged field for the expansion of modernization, in addition to being perceived as an essential condition for the possibility of participation by nations that did not stand out in the consensus of technical-scientific revolutions. In view of this, discursivity of such works was in dialogue with the perception of education as aphorism and panacea to the odds in reaching the total positivists principles, whose pretensions, according to Carvalho (1989, 1997), Souza (1998) and Monarcha (2009), inserted Sao Paulo lands as adages of the Brazilian Education renovation.

In this context, São José do Rio Preto played an emblematic role, since, in reference to Campos (2015), two specific illustrated albums about the torrão paulista, a staple soil mix of Sao Paulo state, besides being, according to Park (1999), the countryside land that most received almanacs. Thus, among these typography products, the Illustrated Album of the County of Rio Preto stands out as a remarkable exemplar to understand this imagery press discursivity, inasmuch as, based on Valle (1994), its pages have been led to encompass the ringed precision genesis of the local history. Nonetheless, the scanning of its particular traces evokes, concurrently, through dialogism that itself sustains and permeates its utterance and uttered, conceptions of education that circulates at the time of its creation and sales, denoting it as a tool for building a verbal-visual panorama of the pedagogical scene in Brazil.

General Characteristics of the Album

According to Arantes (2001), the production on the multi theme Illustrated Album began in 1925, in a temporal period that coincides, according to notes circulating in editions of the newspaper of São José de Rio Preto county A Notícia, of 1929, with the travel and arrival of Abílio Augusto Abrunhosa Cavalheiro8 to São José de Rio Preto County. According to this author himself, such translation was motivated by the fascination that was awakened by the Portuguese immigrant. According to this same author, this transfer was motivated by the fascination that was aroused, in the Lusitanian immigrant, by the idyllic narrative that, at the time, was propagated about that portion of São Paulo in question, which was synthesized as a space that housed the most genuine savagery and the most insignificant development. In this diegesis, the enchantment would come from the dissonance that the plague of Rio Preto had towards the capital of the State of São Paulo, instilling an idea that progress was unfolding in a disharmonic way, as it did not reach the surrounding regions to the Brazilian cities that, at the time, were regarded as modern.

Considering this, the Portuguese artifice guided himself by the prism of endeavoring a social propaganda of all Araraquara Zone, uniting, after arriving at the state capital, with Paulo Laurito9 and Theodoro Demonte10, seeking that these subjects residents of the corner could help to publicize, in verbal and visual spellings, the reality of the territory in focus. To this end, while he collaborated with his renowned photography and editing works, financial aid was intermediated by the first collaborator, who, through the sponsorship of his father, the merchant Carmine Laurito, covered the gaps left by unpaid advertising payments. However, the approximations and tensions originated from and in the relations established by Abílio, in the moments that preceded, intervened and followed the production of the selected typographic work, revealing individual plans he had for the realization of this journalistic material.

From connections that precede the idealization of the mentioned artefact, the ones linked to his friendship to the Santos born artist, under the pseudonym Sylvio Floreal11, whose landmark was publishing the magazine A Flexa, executed by both in the beginning of the 20's, that, due to having a short durability, motivated the two producers to seek success in the west of Brazil. On this endeavor, the confines of Mato Grosso state were the scenario of description and analysis that Sylvio recorded in an illustrated book that was titled O Brasil Tragico, on cardboard paper, while the lands at the northwest of Sao Paulo state were Abílio's center of apprehension. Thus, eager to aggrandize himself in the journalistic circle, unravelling the failure of the aforementioned magazine, the Portuguese headed the making of the Illustrated Album, because, this way, would provide a palpable demonstration of his intellectual prominence, before, including, his friend, since he was renown in the erudite circle.

Soon, the aspired supremacy was bond to the materiality of the object adopted to concretize their utterances, since, as the illustrated album stood out in terms of typographic refinement, in comparison to the illustrated book, the authors of the album symbolically would set themselves in a superior level in relation to the authors of the book. Before this significance, the concreteness of the publication was established as a stage for the implementation of a personal program of its main agent, which can be investigated, for example, with the attempt of silencing Demonte's participation, not included as co-author, despite having made most of the photographs that are in it. With this, the peculiarities of the work that Valle (1994) associated to the failure of sales of his copies, priced at 150 thousand réis and the descriptive conveniences that the presence and absence of payment would impose to his content, can be understood as a refusal to engage in the Portuguese's project and himself.

Among these renounces, the position of the priest Joaquim Manoel Gonçalves is noticeable, someone who, in an appraisal published on the edition from November 10th, 1929 in the local newspaper A Noticia, pointed to gaps in the themes that integrated religion and education, as well as the ones concerning Santo André School12. However, analyzing the specific sections, there are gaps on mentioning the institutions and educational projects fostered by the Catholic Church, but the emphasis and praise are around diligence coming from public resources, both state and municipal, and from the particular effort of citizens that acted in favor of society. Furthermore, as the emphasis placed on this last model of education is intertwined with the presumed carelessness of the government at that time, it is understood that the opinion of the ecclesiastical indicates one of the most salutary conflicts that bound Brazilian education, whatever the dispute in this field for privatists and public convictions.

Therefore, the enunciative inflections coordinated by Abilio were anchored on discursive correspondences of editorial genre and of a press modality that he proposed to the imagery artefact in discussion, for which he could be recognized among those who aligned to a republican ideal of urban social order. From here, subsidies for the discernment of other recurrences established during the 1,093 pages, separated into 22 chapters, in which 1,935 iconographies are included, being four climolithographs, 25 lithographs, 855 ornamental lithographs of other images and some verbal texts, 11 color photographs and 1,040 color photographs. On the one hand, the preponderance of this last pictorial type cited is linked with the most modern technical resources available at the time of its execution, and, on the other hand, with its current proving attribute of the narrowed reality and the consequent improved existence, raising the support to a memory device.

In these pages, even those dedicated to the less affluent portions, we find out, in allusion to Campos (2015), a meticulous chain exerted on and towards educational matters, in which verbal, visual and numbers texts were merged under the mantle of prideful patriotism. To a certain extent, this accent is justified by the fact that such a thematic chain satisfied the historical discourse of the imagery press, which placed its vehicle and the respective locations on the tracks of modernity, and, in another part, on the foundation that Abílio sought in positivist and Kardecist philosophies. Thus, these decisions consolidated, concomitantly with the explicit social propaganda of the Zona Araraquarense, the figure of the Portuguese as the herald of the benefits of the march of regional progress, whose settlement of glorification was symbolized in the large volume of the typography item that he organized.

Considering this, it appears that the outline of the general characteristics of the Illustrated Album of the County of Rio Preto goes through and coincides with the scrutiny of the subject's biographical lines who, for four years, dedicated himself to harvesting and condensing, in a single document, sparse, scarce and multiple records of the villages in retraction. These plots, moreover, guide the apprehension of the factors that encouraged the move of the Lusitanian to the capital of the state of Rio de Janeiro, which are reflected in the recognition that his journalistic work on these backlands acquired in the context of the Getulist regime, although many of the five thousand copies edited by Casa Duprat-Mayença have been stagnant on the shelves of Casa Laurito, where their purchase could be made. Likewise, there is the first and only reprint of the imagery, which, from original units that inhabitants of the interior of São Paulo's state kept, was captained by Roberto do Valle, in 1979, and published by the company Comércio e Indústria Gráfica Francal, years after Abílio's death.

Considering, therefore, that the mentioned reprint was carried out in a graphic park located in São José do Rio Preto, and that the 50-year interval between it and the previous publication corresponds to the period of stabilization of the Lusitanian in journalism, it is made clear that the objectives of the Album, declared and undeclared, were, to a certain degree, achieved. In this same direction, due to the principle of dialogism between the modality of the press and its related products, it is asserted that, with the studied cultural object, portions of the political, market and educational perspectives that structured the discourse of the imagery press were reached. Finally, the highlighted reiteration and resignification of the fabric between the utterance and the enunciator marks that the transmitted verbal-visual representations of education, its inseparable support, and thematic topic, crossed the narratives of the cultivated history as to be remembered and perpetuated.

Graphical representations of education

In the Illustrated Album of the County of Rio Preto, the topics linked to education are embodied in each of the parts destined to the territories that, between 1925 to 1929, were under the jurisdiction of the plague that had its name marked in the title of that work, including in those corresponding to the spaces of diminished extension and of scarce financial resources. However, while, in the specific fragments for the more affluent soils, the statement about education occupied particular galleries about schooling, it was involved, in the segments of the other districts and municipalities, in subtitles of sections of social life and about the improvements promoted and to be done by all spheres of political administration. Even so, in a similar way, this issue was manifested with the help of numbers, to expose reservations to private projects, considering that, while indicating a citizen-like concern of those who wove them, they elucidated a certain ineffectiveness of real possibilities to the public government.

These mathematical symbols, which, according to Pêcheux (2006), regulate a logically stabilized universe for discourses, are arranged in some pages, with the purpose of specifying the number of students, classes and formal educational institutions, discerned by nomenclature, location, nature and their maintainer. In parallel, the figures were listed, to indicate the number of inhabitants of each of the clods that constituted the then social propaganda of the Araraquarense region, and to discriminate the census number of their children, increasing the portion of it that was not enrolled in at least one of the schools. Because of this, the scenario conveyed by the aforementioned piece of typography stimulated the confrontation of the proportion between the number of schooling initiatives and the total population of the circumscribed stops, and, at the same time, encouraged the improvement of the conditions set as existing, and symbolized childhood as the main focus of the education being advocated for.

Despite the eager engagement with this quantification, there were some gaps in the information collected by the Portuguese artifice, corresponding to the total coefficient of residents in certain parcels, the typology and the support entity of the teaching buildings that were not public, and the amplitude of the census carried out about school-age infants. On the other hand, the 103 catalogued educational establishments were named, of which 38 were run by private projects, 17 were exclusively controlled by the public sphere, and 48 did not have this element mapped, although they concentrated, in 15 classrooms, 1,027 students. Within these last three categories, there are 39 educational institutions characterized as not functioning, due to the fact that, despite having exclusive environments for the execution of pedagogical works, there were no teachers of any disciplines, and neither, students with active records.

However, considering a population of 32,700 human beings, another 6,251 were found in the current school records, of which 2,506 were distributed in 22 private classes and 3,745 were apprentices from 64 classes of public organizations, comprising, with those of the institutions of a non-delimited stratum, 7,278 students. Considering this, it appears that, although the number of declared private enterprises is greater than that of government prescription, they had a higher number of classes and academics, inflating considerations on the conditions of teaching, although professional teachers have not been listed on the publication. Complementing this reflection, the concerning signs to the listing of 11.038 school-aged boys and girls as already being in the traditional teaching-learning process, among which 985 were in accordance with the required statics, whereas 10.053 endorsed the elucubration defended by the pledged discursive monophony.

Before such scheme, a distance from the 1920 Census is set (4th General Census of the population and 1st of the agriculture e industries) (Brazil, 1926), which, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade, was carried out in September that year and published in 1926, by the Statistics Typography. In this document from the General Directorate of Statistics, in which Brazilian citizens are ordered by states, municipalities and districts, and separated according to sex, marital status and nationality, the population of the geographical divisions in which the judicial management of Rio Preto exercised its authority encompassed 126.796 inhabitants. However, this discrepancy was alarmed in a footnote to the Album, in which the chief physician of the Rio Preto's Hygiene Post, Espiridião de Queiróz Lima, pointed out that there was a lapse in the capture of some of these data expressed in the artefact, through which more complete bases that the engineer of the City Council had were disregarded.

In this way, despite this caveat, the sense propagated by the social advertising device converged to the same considerations that could be deduced by the demographic inventory, denoting that Alta Araraquarense shone between the areas of higher housing density, due to being an interior state region. With regard to the education scene, the notability fell on the buildings of instruction, of rural and urban circles, because these, even if they were not provided with any type of teacher, had characters that made them unique and magnified them, to the point of making them recognizable in comparison to other properties. However, such properties had a symbolic connotation, given that, in the section entitled 'The great problems of Rio Preto', its Portuguese writer pointed out that one of the causes for Riberão Preto's progress, which was the archetype of civilization due to its surroundings, was the local construction of normal, elementary, gymnasiums and high schools.

According to Souza (1998), the rise of the garish school groups in São Paulo, within a political project of a republican nature, was central to the memorialistic sedimentation on the visual identity of educational institutions aligned with modern democratic teaching proposals, which were guided by Europeans and Americans. For Carvalho (1989, 1997), these majestic buildings also served for a behavioral disciplinarization of citizens, as their physical implantations were made congruent to the alteration of the entire adjacent territorial space, in a way that enshrined its relevance for social culture, and mobilized a certain reverence posture from these subjects. As an instigator and consequence of this panoply, photographic albums of schools were produced, which, according to Abdala (2013), strengthened, by the articulation between words and iconographies, the creation of a discourse and an image of their buildings, their practices and of their personas, in a narrative for the rational and affective apprehension of these supports and content.

In Rio Preto, according to studies by Pinheiro (2004), another component of this exercise of standardizing the population, in which the configuration of urban reforms in the landscapes was one of the main pedagogical resources, was its Local governmental Laws, promulgated in the last month of 1902, by the municipal steward of the occasion. In the 233 articles of this legislation, Emygdio de Oliveira Castro methodized appropriate and inadequate conducts to residents and sectors of activity on such a surface, which were marked by the bastion of morals, hygiene and productivity, whose non-compliance was liable to fine payment to the government, and, in some situations, imprisonment. In this regulation, in spite of the absence of explicit lines concerning the schools, its diffuse coverage is made in the chapters attributed to the buildings, in which the size and position of passers-by passages, gardens, walls, blocks, doors and windows are scrutinized of any civil works that were built on the Rio-Pretense perimeter.

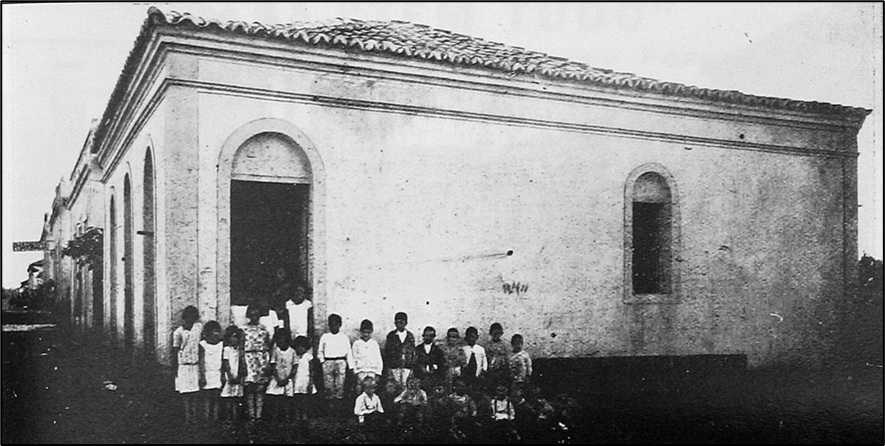

Because of this, it is not innocuous to realize that, of the 21 photographs that were identified as having an educational theme, six are from school facades, six are from groups of students from a certain educational institution, four are from individual portraits of teaching professionals from different levels, two are for educational activities, and two are for groups of educators. Within this set, the first portrait to break out in the linearity of the final edition of the artefact was the one that contains the external and complete appearance of the first school group in Rio Preto, which, as shown in Figure 1, is in a rectangular cut-out, with vestments of lithographs in art nouveau, on its right and left sides.

Source: Cavalheiro & Laurito (1929).

Figure 1 Rio Preto's First School Group, built by the State Government in 1916.

In such a photograph, the capture of the educational institution is made by its diagonal, in a slightly ascending angle, without margins for any human being, having, in its foreground, the presence of the intrinsic garden, with sidewalks, benches, lamps and trees in initial growth stage, and in the second, the main school building and its two annexes. Considering this, also as Campos (2015, 2017) observed, the photographer's technique, in this image, leads to the assimilation of the monumentality of this construction itself, which, following a neocolonial architectural project in line with the rules outlined in the Local Governmental Laws of Rio Preto, contained bright windows that suggested, in conjunction with hygiene, the irradiation of knowledge.

Source: Cavalheiro & Laurito (1929).

Figure 2 General view of the Barra Dourada School Group, where several students can be seen.

The School Group of Barra Dourada, in turn, was photographed accompanied by a teacher and 26 students, some standing and others sitting, in an effort, perhaps, to attest to its characteristic of a formal education institution, since this characteristic was not inferable by the respective construction, which, simple, matched that of the neighboring pharmacia. Despite this simplicity, the image was cut out in a rectangular shape, captured in a diagonal perspective on the right, with an angle perpendicular to its central point, and three compositional levels, which show that the school was located on the lower border of the block of a sloping street, with other buildings in its surroundings. Because of this spatial aspect, Figure 2 suggests the ancestry and the importance of the educational establishment itself, since, having this concentrated in almost the integrality of the photo background, as a result of the side click, the other portrait surfaces participate in the scenery, increasing the visibility of the former.

With these two thematic images about school institutions, there is a pattern in the technique of realization and in the publication of the iconographic record, in which, with primacy of its diagonal and ascension prism, the buildings are included in the second and largest plane of the photo, with a rectangular shape, giving an ornamental flow to its two other levels. In addition, Figure 1 portrait was adorned with typographic lithographs, in a character that, in the aggregation of the verbal-visual linguistic spheres, shows, alluding to the consecrated sentence by Souza (1998), the sumptuousness of this temple of civilization, which met the then current educational building guidelines. Furthermore, Figure 2, as well as three other photographs of the educational institutes displayed in the Album, was enriched with the school subjects, who, accommodated in the frontal position of the building, prove its educational design, and therefore inspire the arguments around the urgency and primacy of popular education.

Source: Cavalheiro & Laurito (1929).

Figure 3 A group of students from the School of Ubarana, seeing, standing on the right, the gracious and dedicated teacher of the Group, and in the background, standing, several prominent people from Ubarana's society.

Sharing this same photograph and exposure measure in the listed typographic object, is Figure 3, which, from a rectangular cut-out, students, teacher and figures from Ubarana's society pose and are captured diagonally to the right of the scene, at an angle perpendicular to the lens of the portrait artist's apparatus. Formed by four plans, in the background, disclosing the then only educational institution of the mentioned location, and, in the front, children of different ages and economic situations, fitting, with shoes, light clothes and the central sofa, and, barefoot, dark clothes and the lower edge of the painting, close to the teacher's feet. In this, intensifying the idyllic inflection of the message of the pictorial item, the master, with a book in her hand and wearing a dark dress printed with clear geometric lines, found at the threshold of the second and third levels of the iconography, suggest, such as a holiness, its role in transforming social ills.

Source: Cavalheiro & Laurito (1929).

Figure 4 A group of dactylography students from School D. Pedro II from Rio Preto seeing to the right of the machine in the center one of the senior teachers. Enoch de Moraes e Castro.

According to this examined principle, there is Figure 4, which, on three levels, presents young typing students, arranged in the intermediate plane of the portrait, and, in the frontal view, the teachers of the respective course, sitting with crossed legs and arms, flanking the main material resource of the activities developed by them. Delimited by a rectangular cut-out, the image was captured in a central position and with a perpendicular angle, having, in its printing in the Album, ornaments of lithographs of the same artistic axis and positioning of Figures 1 and Figures 3, and an iconographic density, resulting from the hue dark of their subjects' clothes, broken by the lining of the machine base. Thus, corroborated by the respective caption, the photo in Figure 4 reinforces the portrait elements present in the other iconographies with school-aged subjects, but includes a new message, which is based on the nominal identification of the teacher and the centrality of teaching material

Source: Cavalheiro & Laurito (1929).

Figure 5 Students of the School of Dactylography ‘Olivetti’ composed of a group of gifted ladies from our ‘social elite’.

As analyzed in the previous pictorial artefact, the heart of Figure 5, clicked in a central and perpendicular prism, is the typewriting machine, which, placed on top of the Brazilian flag that covered a table, is surrounded by teachers and young students of such a written technique, which accommodated themselves in the studio that served as a backdrop for other prints by students and teachers. Keeping the constancy of photography of apprentice subjects, the image has three levels of composition, and in the first two, such characters are placed in rows, in which the front ones were seated, while the rear ones were standing, and, in the last plan, the iconographic landscape of a castle remained. In addition, there is the demarcation of the most open nuances for women's clothing, and the recurrence of the more closed range for men's clothing, the crossed position of the upper and lower limbs of the abandons, and the austere countenance of all, in addition to the items that differentiated masters from students, who, in this case, converged on light shoes.

Faced with this theme gallery on school-age subjects, a second type of paradigm of effectuation and placement of photographic records of educational nature is detected in the Album, in which, with a preeminence of centralized and perpendicular optics, students are included in the first and flat intermediaries plans, and arranged in sequential rows. In addition, as most of these images being taken in a studio environment, the number of students portrayed is very limited, compared to the 7.278 students drawn in numerical data, which encouraged the ratification of the claim that the number of students outside of schools was great. In this way, having preserved the rectangular shape and the magnificence enhanced by the adornments of lateral lithographs announced in the photographs of an educational institution, those of academics point out the inherence that exists between place, individuals, practices, materials and political projects, in the appropriate statements about the education.

Final considerations

The Illustrated Album of the county of Rio Preto is greatly correlated to the characteristics and objectives of the imagery press, which was conceived by the Portuguese Abílio Augusto Abrunhosa Cavalheiro, as soon as he landed on the ground of the municipality where this jurisdiction was located, in 1925, after deciding to travel with his friend Sylvio Floreal, towards the west of Brazil. Presumably fascinated with the divergences identified between what he observed in these plains in the state interior of São Paulo and what was socially proliferated in that region, the Portuguese journalist led the production of the mentioned typographic piece, in order to demonstrate the reality of the listed territory, and to raise plural investments towards this. To this end, it constructed a narrative of conciliation of verbal and visual texts, dividing, for this dimension, the photographic technique, widespread as of proving content, and, for that, distinct discursive genres, which, in turn, were based on digits denoting investigative integrity.

Thus, the imagery publication was conveyed as a historical document, as it contains the so-called true origin of the Rio Preto's perimeters, and, because it encompasses the logic inherent to the numbers coming from suitable sources, as the landmark of the sedimentation of the early rationalism, and burial of the diegesis that swarmed on that theme. Having this in consideration, combined with the idiosyncratic prolixity of the writing of its Longroiva born organizer, this press apparatus reached a dense corporeity, which differentiated it from its editorial peers, who were recurrent political instruments, from the government and private sphere, in the search for the establishment of an urban social order. Therefore, Abílio's journalistic diligence was also detached to a symbolic aspect, considering that, in spreading the robustness of a typographic item in which he was an active participant in all stages, his image acquired the same contours, guaranteeing him certain notability within the social group it was part of.

In this discursive direction, the educational bias manifested itself in two expressions, both in the enunciative, when referring to the memory of the one who presented himself as its author, and in that of the utterance, through a polysemy of published writings and pictorial items, which were related in a reciprocal determination. On the one hand, this convergence was based on the attempt to create a monophonic panorama, in which the opinions of erudite individuals were exposed and conducted under the desirable one-sided systematization of Portuguese, and, on the other, in the circulating discourses at the time, which inferred country regeneration was subject to popular instruction. However, the analysis of that double exteriorization demonstrated that the presence of other voices triggered the polyphony inherent in historical discursiveness, which was concealed, due to the efforts that his discursive subject expended to verbiage, demarcating a simulacrum of argumentative harmony.

In this same sense, it was found that, despite their propagated irrefutable aspect, the photographs, which occupied most of the visual dimension of the typographic work analyzed, had the role of building realities, being assisted with lithographs inserted in their sides, and with captions and other accompanying writings. The vignettes were responsible for adding to the central theme of the photo, discriminating it as the archetype of those who shared it, while verbal inscriptions were given the task of collaborating with the reading of the engravings, adding information that was not subject to photographing. Soon, it was found that the images were used as partial discourses interrupted in their context, having, in their own palpability, elements that widened their limits generated by the cutouts applied by the photographer, which were emphasized by the composition and editing strategies of the page where they were published in.

Thus, the meaning of the message sought by the producers of such publication was immanent from the agglutination between the plural iconographic and alphanumeric texts, resulting from a dynamic of democratization very peculiar to its typographic circumscription, in which the reader's accessibility to a non-erudite public was aspired by the use of figures. Consequently, a scope of utterance was created in verbal-visuality, which, as a result of that unification, was characterized as the discursive pattern of the Album, fulfilling the triple purpose of disseminating certain technical robustness, carrying out social and familiarizing the immediate recipients with a corporate order.

Therefore, the discursive clusters about educational content denote that, based on the captions and iconographic constitutions, the very enunciation of the Album was of an educational bias, insofar as it stimulated the visualization and recognition of the argued problems of society, and highlighted the behavioral and pragmatic paths of resolution. In other words, the recurrence of concrete discourses about education emerges from this content as inherent to its enunciation scene, which implies its establishment in the social applicability of the cultural object examined, which can be synthesized as an update of the discourses that circulated in the then society, through a visual, ethical, aesthetic and, why not, linguistic educational practice. Finally, this artefact, as a sphere of political and cultural action by agents who intended to act in the literal cure of a sick clod, was not only the showcase of proposals for the modernization of society, but became the verb-visual epiphany of civilizing projects they had popular and official instruction of a São Paulo state mold as the heart of progress

REFERENCES

Abdala, R. D. (2013). Fotografias escolares: práticas do olhar e representações sociais nos álbuns fotográficos da Escola Caetano de Campos (1895-1966) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Arantes, L. (2001). Dicionário rio-pretense: a história de São José do Rio Preto de A a Z. São José do Rio Preto, SP: Casa do Livro. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (2011). Estética da criação verbal. São Paulo, SP: Editora WMF Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (2006). Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem. São Paulo, SP: Hucitec. [ Links ]

Barbuy, H. (1996). O Brasil vai a Paris em 1889: um lugar na Exposição Universal. Anais do Museu Paulista, 4(1), 211-261. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/anaismp/v4n1/a17v4n1.pdf [ Links ]

Brait, B. (2013). Olhar e ler: verbo-visualidade em perspectiva dialógica. Bakhtiniana, 8(2), 43-66. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/bak/v8n2/04.pdf [ Links ]

Brait, B. (2011). Polifonia arquitetada pela criação visual e verbo-visual. Bakhtiniana, 5(1), 183-196. Recuperado de: http://revistas.pucsp.br/bakhtiniana/article/viewFile/5397/5091 [ Links ]

Brasil. (1926). Recenseamento de 1920 (4º censo geral da população e 1º da agricultura e das industrias) (Vol. 1, 1a parte). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Typ. da Estatistica. Recuperado de: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv6461.pdf [ Links ]

Campos, R. D. (2017). Os álbuns ilustrados do sertão paulista: a modernidade encarnada (1900-1930). EDUR Educação em Revista, 1(33), 1-32. Recuperado de: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/edur/v33/1982-6621-edur-33-e162511.pdf [ Links ]

Campos, R. D. (2015). Relatório de estágio de pós-doutorado (Relatório de Pós-doutorado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (1997). Educação e política nos anos 20: a desilusão com a República e o entusiasmo pela educação. In H. C. Lorenzo & W. P. Costa (Orgs.), A década de 1920 e as origens do Brasil moderno (p. 115-132). São Paulo, SP: Editora da Unesp. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (1989). A escola e a República. São Paulo, SP: Editora Brasiliense. [ Links ]

Carvalho, V. C., & Lima, S. F. (2008). Fotografia e cidade: da razão urbana à lógica do consumo - álbuns de São Paulo (1887-1954). Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Cavalheiro, A., & Laurito, P. (Orgs.). (1929). Album illustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929). São Paulo, SP: Casa Editora Duprat-Mayença. [ Links ]

Certeau, M. (2011). A escrita da história. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Forense. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. (2002). A história cultural: entre práticas e representações. Lisboa, PT: Difel. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. (2014). A mão do autor e a mente do editor. São Paulo, SP: Editora UNESP. [ Links ]

Cohen, I. S. (2013). Diversificação e segmentação dos impressos. In A. L. Martins & T. R. Luca (Orgs.), História da Imprensa no Brasil (p. 103-130). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Fiorin, J. L. (2006). Interdiscursividade e intertextualidade. In B. Brait (Org.), Bakhtin: outros conceitos-chave (p. 161-193). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Fiorin, J. L. (2008). Introdução ao pensamento de Bakhtin. São Paulo, SP: Ática. [ Links ]

Kuhlmann Jr., M. (2001). As grandes festas didáticas: a educação brasileira e as exposições internacionais (1862-1922). Bragança Paulista, SP: Editora da Universidade de São Francisco. [ Links ]

Maia, C. (2007). Introdução. In A. Mendes & W. Moreira (Orgs.), A Semana Ilustrada: história de uma inovação editorial (p. 5). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Secretaria de Comunicação. [ Links ]

Martins, A. L. (2013). Imprensa em tempos de Império. In A. L. Martins & T. R. Luca (Orgs.), História da Imprensa no Brasil (p. 45-80). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Mason, A. (2003). O surgimento da era moderna: 1900-1914. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Reader’sDigest. [ Links ]

Mendes, A., & Moreira, W. (Orgs.). (2007). A Semana Ilustrada: história de uma inovação editorial. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Secretaria de Comunicação. [ Links ]

Monarcha, C. (2009). Brasil arcaico, Escola Nova: ciência, técnica e utopia nos anos 1920-1930. São Paulo, SP: Editora UNESP. [ Links ]

Nunes, C., & Carvalho, M. M. C. (2005). Historiografia da educação e fontes. In Gondra, J. (Org.), Pesquisa em história da educação no Brasil (p. 17-62). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: DP&A. [ Links ]

Oliveira, M. C. (2001). Os almanaques de São Paulo como fonte para pesquisa. In M. Meyer (Org.), Do almanak aos almanaques (p. 23-24). São Paulo, SP: Ateliê Editorial. [ Links ]

Orlandi, E. P. (2003). A análise de discurso em suas diferentes tradições intelectuais: o Brasil. In Anais do 1º Seminário de Estudos em Análise do Discurso (18 p.). Porto Alegre, RS. Recuperado de: http://www.ufrgs.br/analisedodiscurso/anaisdosead/1SEAD/Conferencias/EniOrlandi.pdf [ Links ]

Orlandi, E. P. (2005). Análise de discurso: princípios e procedimentos. Campinas, SP: Pontes. [ Links ]

Park, M. B. (1999). Histórias e leituras de almanaques no Brasil. Campinas, SP: Mercado das Letras. [ Links ]

Pêcheux, M. (2009). Análise de discurso. Campinas, SP: Pontes Editores. [ Links ]

Pêcheux, M. (2006). O discurso: estrutura ou acontecimento. Campinas, SP: Pontes Editores. [ Links ]

Pereira, M. S. (2010). A exposição de 1908 ou o Brasil visto por dentro. Arqtexto, 1(16), 6-27. Recuperado de: https://www.ufrgs.br/propar/publicacoes/ARQtextos/pdfs_revista_16/01_MSP.pdf [ Links ]

Pinheiro, A. C. (2004). O código de posturas do município na educação e normatização do “povo” (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de Campinas, Campinas. [ Links ]

Prost, A. (2014). As palavras. In R. Rémond (Org.), Por uma história política (p. 295-330). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Editora FGV. [ Links ]

Ramos, E. A. (2009). Origens da imprensa ilustrada brasileira (1820-1850): imagens esquecidas, imagens desprezadas. Escritos III: Revista do Centro de Pesquisa da Casa de Rui Barbosa, 3(1), 285-309. Recuperado de: http://www.casaruibarbosa.gov.br/escritos/numero03/FCRB_Escritos_3_14_Everardo_Ramos.pdf [ Links ]

Sodré, N. W. (2004). História da imprensa no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Mauad. [ Links ]

Souza, R. F. (2000). Um itinerário de pesquisa sobre a cultura escolar. In M. V. Cunha (Org.), Ideário e imaginário da educação escolar (p. 3-27). Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Souza, R. F. (1998). Templos de civilização: a implantação da escola primária graduada no Estado de São Paulo (1890-1910). São Paulo, SP: Editora UNESP. [ Links ]

Valle, D. (1994). A notícia. São José do Rio Preto, SP: A Notícia. [ Links ]

Valle, R. (1979). O Álbum, fixação de um tempo. In A. Cavalheiro & P. Laurito (Orgs.), Album illustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929). São José do Rio Preto, SP: Francal. [ Links ]

7With the emphasis in italic, the original nomenclature given to the work, as well as some expressions of the period under study, will be written. However, in order to avoid the repetition of the alias Album Illustrado da Comarca de Rio Preto (1927-1929), the following terminologies will be used as equivalents throughout this text: Illustrated Album of Comarca de Rio Preto - capital letters, but without time demarcation and any type of italics; Illustrated Album - capital letters, but without space-time demarcation and any type of italics; and, Album - with capital letters and without any type of italics.

8Abílio Augusto Abrunhosa Cavalheiro was born in Longroiva, Portugal, on June 11, 1891, where, motivated by his own family context, he sought to become professional in his legal career. However, in 1918, with the effervescence of the politics of his native country, which was aggravated by the outbreak of World War I and the debauchery generated by the pneumonic flu, he went to Brazil, and began to perform employment activities different from those in which he was being instructed. Among these, it was those of the journalistic sector that remained constant throughout their life trajectory, which ended on December 31, 1966. In the lands of the northwest of São Paulo, for example, in addition to the Álbum Ilustrado of the Comarca of Rio Preto, the Longroiva born founded, in 1925, Rio Preto Jornal, having been editor and editor of the editions of this typographic periodical and of the Diário de Catanduva.

9Paulo Laurito was born in Franca, Brazil, on January 24, 1898, to Italian immigrants Carmine Laurito and Josephina Pezzutti. In 1910, in the company of his parents, he moved to Rio Preto, where he remained until his death, which occurred on November 25, 1968. In the year 1925, he was director and editor of the magazine A Phalena, owned by his father. After the publication of Álbum Ilustrado, which led his whole family to bankruptcy, in 1930 he acted as director of the local newspaper O Municipio, when he also founded, in partnership with the ferreirense Antônio Muffa, the typographical periodical A Época, of Getulist tendency.

10Theodoro Demonte was born in São Paulo, São João da Bocaina, at a date still unknown. A direct descendant of Italian immigrants, he is recognized as the first filmmaker in Rio Preto and as one of the first photographers in the State of São Paulo to produce sepia-toned portraits. In his vital journey, which ended on May 12, 1964, he and his brothers José, Pedro and Lauro were famous for the nickname 'Irmãos Demonte', especially after creating, in 1920, the 'Demonte Filmes e Cinematografia Progresso', through which they achieved the pioneering art of producing and projecting, in such a federative share, films resulting from the sequential ordering of static photographs.

11Sylvio Floreal was the fictitious name that Domingos Paes Alexandre attributed to himself, when signing chronicles, novels and other textual genres that he wrote. Born in 1892, in Italy, he moved, still young and without the company of immediate ascendants, to Brazil, where he resided until 1928, when a sudden illness ended his life. Despite not having even attended the elementary level of formal education, he was an avid reader of Brazilian and foreign literary works, which, in addition to serving as a compositional inspiration, were his main companies. Among his written productions, the Midnight Round stands out: addictions, miseries and splendours of the city of São Paulo, dated 1925, in which the Italian portrays, from his observation and experience, the night life of the society of capital of São Paulo in the years 1910 and 1920, providing a spectrum of what was on the margins of the talked about modernization.

12Colégio Santo André was founded, in São José do Rio Preto, on March 12, 1920, and constituted itself as the third Brazilian institution of the educational mission of the Catholic Congregation of the Sisters of Santo André, whose pedagogical principles were marked out in and adapted from Santo Inácio de Loyola. In Brazil, this apostolic community, of Belgian origin, started its activities in the city of Jaboticabal, in 1914, and in the municipality of Araraquara, in 1916, due to an invitation from the bishop of São Carlos, which it aimed to have, in the diocese under the its direction, two schools for girls. In this context, in the Rio-Pretense conjuncture, this College was, for some years, the only establishment dedicated exclusively to the training of young women, which caused an increase in the number of students enrolled, and, therefore, a need for larger buildings. and other school spaces, for the development of their educational practices. Currently, of the six remaining Brazilian communities of the Congregation of the Sisters of Santo André, only those of Jaboticabal and Rio Preto keep their schools running.

20Note: This paper is the result of the research The Illustrated Album of the Rio Preto County and the enunciated education (1920-1929): stories, memories and identities encouraged in verbal-visuality, financed by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES). Such investigation was developed as a result of the projects 'The Illustrated Albums of São Paulo backwoods (1900-1954): production, circulation and materiality' and 'The Illustrated Albums of the São Paulo backwoods: the incarnated modernity (1900-1930)', subsidized by the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG).

Received: December 27, 2019; Accepted: June 02, 2020; Published: November 27, 2020

texto em

texto em