Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.21 Maringá 2021 Epub 02-Dic-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e144

ARTICLE ORIGINAL

A mulher soldado on stage (São João Del Rei, Minas Gerais, 1916): an operet in scene educating sensibilities

1 Universidade Federal do Agreste de Pernambuco, Garanhuns, PE, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil.

Abstract The presentations of the operetta A mulher soldado in São João del-Rei - MG (1916) were highly appreciated by the public and the press and were configured as performances that educated sensibilities. This article analyzes the play's manuscript, local newspapers and a local author play, from sources found in the collection that belonged to the amateur group responsible for the shows. Weseek to understand the education of the sensibilities that would have occurred during these performances. Supported by studies of the History of Education of the Sensibilities, we identified that the shows, while reinforcing sensibilities linked to male domination, imposed by a dominant elite, allowed people sympathetic to the feminist struggle to experience new sensibilities.

Keywords: history of education of the sensibilities; gender; history of spectacles

As apresentações da opereta A mulher soldado em São João del-Rei - MG (1916) foram muito apreciadas pelo público e pela imprensa e se configuraram como performances que educaram sensibilidades. Este artigo analisa o manuscrito da peça, jornais locais e uma peça são-joanense do período, fontes encontradas no acervo que pertencia ao grupo amador responsável pelos espetáculos. Buscamos compreendera educação das sensibilidades que teria ocorrido durante essas encenações. Apoiadas nos estudos sobre a história da educação das sensibilidades, identificamos que os espetáculos ao mesmo tempo em que reforçavam sensibilidades ligadas à dominação masculina, impostas por uma elite dominante, davam margem para que pessoas simpáticas à luta feminista experimentassem novas sensibilidades.

Palavras-chave: história da educação das sensibilidades; gênero; história dos espetáculos

Las presentaciones de la opereta A mulher soldado en São João del-Rei (1916) fueron muy apreciadas por el público y por la prensa y se configuraron como performances que educaron sensibilidades. Analizamos el manuscrito de lapieza, periódicos locales y una pieza sanjoanense del período, fuentes encontradas en el acervo que pertenecía al grupo responsable por los espectáculos. Buscamos comprender la educación de las sensibilidades que podrían Haber tenido lugar en esas presentaciones. Apoyadas en los estudios sobre la historia de la educación de las sensibilidades, identificamos que los espectáculos al mismo tiempo que reforzaban sensibilidades vinculadas a la dominación masculina, daban margen para que las personas simpatizantes conla lucha feminista experimentas en nuevas sensibilidades.

Palabras clave: historia de la educación de las sensibilidades; género; historia de los espectáculos

Introdução

The research that led to the present article sought to understand the education of sensibilities that took place from theatrical performances by an amateur theater group, in the city of São João del-Rei, Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 191637. According to Oliveira (2018), the History of Education experienced, in the last 20 years, “[...] an inflection towards the senses and sensibilities [...]”, enabled “[...] by the renewal of studies in History of Education and their close relationship with the History in Latin America field” (Oliveira, 2018, p. 120). Although interest in the theme of senses and sensibilities is not something new among historians, Oliveira (2018), as well as Pineau (2018), more recently identified what for the latter is about an ‘affective turning point’ in the field.

Pineau (2018), going through investigations in the field of history of education on aesthetics and sensibilities in Latin America, observes a change concerning study objects. For the author, there is an ‘affective turning point’; researchers turn to the analysis of subjects, discourses, forms of distribution, production and appropriation of knowledge and practices linked to the sensitive world. Pineau (2018, p. 2, author’s emphasis, our translation) 38 states that

Although traces of these themes are trackable in previous works - for instance, in stories dealing with childhood, curriculum and teacher training -, the effects of the so-called ‘affective turning point’ (Lara & Enciso Domínguez, 2013; Macon & Solana, 2015) in recent times have allowed new contours and more in-depth analyses by means of the construction of specific approaches. This thematic ‘turning point’ in the social sciences - with special emphasis on the impulse led by anthropology - configured a change in the production of knowledge on issues such as affections, sensibility, emotions and tastes, mainly recognizing their cultural and historical variability (Lutz & White, 1986).

The investigation herein presented is attuned to the ‘affective turning point’ trend in the social sciences and, as Oliveira (2018) teaches us, given the recognition of the limits of stories of a generalizing character, seeks to understand the materiality of life, the responses that people give to the different situations they experience, the sensibilities involved in these situations. It also aims to apprehend, in addition to the discourses, how one reacted to them, that is, “[...] to understand the emotional responses of different individuals to social demands” (Oliveira, 2018, p. 121).

We therefore analyze the sensibility education processes experienced in theater shows that took place in São João del-Rei, in 1916. It is important to highlight that, between the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, that city was undergoing intense transformations. Technological innovations, such as the railway, electricity, telegraph, the industry, printing and the development of the local press changed the public space, the modes of sociability39. The times and spaces for work, leisure and socialization were being transformed. In addition to traditional religiosity, represented by Catholic masses and traditional religious festivals, São João del-Rei had several spaces for sociability and various forms of leisure. São João del-Rei people watched and participated in football championships40, went to cafes and to the movies41, watched circus and theater shows presented by itinerant companies, by amateur groups and by professionals from the city.

In this context, Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo aimed to provide outstanding performances, thus proving the ‘high degree of civility’ of those people42. Led by high-ranking military men, men of letters and from the government, the amateur theater group was made up of local artists, men, women and children from São João del-Rei elites. It performed operettas at the Municipal Theater, which, albeit criticized by the literati of the period, were much applauded in cities deemed ‘advanced in civilization’, such as Paris, Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro.

From the repertoire staged by the group, the Portuguese version of the French operetta A mulher soldado [The female soldier] was selected for the scope of this article, which was a major success as to audience in said cities and highly acclaimed by the local press. Though much staged and applauded, this play, alongside others, was severely criticized by French men of letters of the 19th century for being characterized as ‘light play’, ‘easy as to its genre’ and ‘too obscene’. However, at the beginning of the 20th century, the operetta genre comes to symbolize a typically French art43, a heritage of that nation, but still faced criticism from those who were for a ‘civilizing theater’ in Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro.

The choice to analyze the stagings of this operetta was founded on the notion of ‘poetics’ elaborated by Zumthor (2007). According to the author, the discursive practice of ‘poetics’ is different because it is capable of generating effects, of providing pleasure. We take theater as a poetic discourse, and theater shows as performances, the only living way of poetic communication for the author. The popular success, recorded by the press, and the repeated presentations are evidence that these shows were constituted as performances, moments that provided pleasure to those involved. For Zumthor (2007, p. 68), performance, a “[...] full presence, charged with sensory powers, simultaneously vigilant [...]”, changes knowledge and not only communicates. We add to the author’s definition the presence of different sensibilities during poetic communication. Thus, the stagings of the operetta were configured as educational phenomena, moments in which listeners and interpreters, in interaction, carried out and constituted, at the same time, a poetics.

Inspired by the notion coined by Pesavento (2007)44, we created distinctions between individual, collective and hegemonic sensibilities. We define as individual sensibilities the imaginary operations of sensemaking and representation of the world, which allow reliving, by the power of thought, singular sensitive experiences regarding an event lived by a certain subject; collective sensibilities are the imaginary operations of sensemaking and representation of the world related to common experiences. These operations produce, by the power of thought, modes of feeling as belonging to specific social groups; and hegemonic sensibilities are imaginary operations of sensemaking and representation of the world that dominant groups seek to impose on other social subjects.

Methodology and Sources

The main archive used for conducting the research is maintained by the Performing Arts Research Group [Grupo de Pesquisa em Artes Cênicas] (GPAC) of the Federal University of São João del-Rei [Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei] (UFSJ). Rocha Junior (2006), coordinator of the group, states that the archive was composed of two collections: the first belonged to Clube Teatral Arthur Azevedo, an association of amateurs from the city, which operated from 1905 to 1985, had a library with about 8,000 volumes on the most varied themes and “[...] approximately one hundred and twenty handwritten and/or typewritten texts, and another one hundred and eighty texts, with numerous traces of montage” (Rocha Junior, 2006, p. 71).

A second collection was added to this set of sources: the private archive of Antônio Manoel de Souza Guerra, better known as Antônio Guerra, who had been involved with theater since he was 13 years old, was an actor, rehearser, prompter, founded and participated in some amateur theater groups in São João del-Rei and other cities in Minas Gerais.

Antônio Guerra was the secretary of Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo when it was inaugurated, in 1915. According to the association’s statutes, the secretary had the duty to organize the club’s bookkeeping, minutes book, “[...] copies of letters sent, albums with press opinion clippings and program collections, files [...]”45. Guerra did so and seemed to have taken a liking to the craft because, wherever he went, due to his job as a manager at Singer, he collected press notes and theater programs. With this material, he made 13 albums that are now available at UFSJ. These albums contain photographs, postcards, tickets and show schedules, clippings from the region’s newspapers with critiques and news about theater, as well as copies of the newspapers published by two amateur theater clubs of which he was a member: the newspaper O Theatro, Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo’s official body, published by São João del-Rei’s organization, and the newspaper O Theatro, published by Club Dramático Familiar de Lavras46.

In 1968, the amateur published his book: Little History of Theater, Circus, Music and Varieties in São João del-Rei 1717 to 1967 [ Pequena história de teatro, circo, música e variedades em São João del-Rei 1717 a 1967], written from his collections and memories. In this article, we take Guerra’s book as a source, in addition to album 13, composed of a material dated from 1915 to 1929. That album contains copies of the newspaper published by the amateur club, which was distributed for free on the days of the shows47, in addition to 101 newspaper clippings, taken from 11 different periodicals48, published in São João del-Rei.

Another important set of sources is the theatrical texts analyzed, which are arranged, in alphabetical order, on one of the shelves reserved for the plays of the archive. We used the handwritten copy of the operetta49A mulher soldado, or Vinte e oito dias de Clarinha [Clarinha’s Twenty-Eight Days], which is a version by Gervasio Lobato and Acacio Antunes of the vaudeville-opérette Les vingt-huit jours de Clairettes, in four acts, by French composer Victor Roger and writers Hippolyte Raymond and Antony Mars Vapereau (1893). We also used the vaudeville Santo Antônio nas Águas [Saint Anthony in the Waters], written in 1911 by Severiano de Resende, from São João del-Rei, which is found in the archive in a typewritten version.

In order to approach the education of sensibilities that occurred during the stagings of the operetta A mulher soldado, we were inspired by Williams’ ‘dramatic-analysis method’ (2010). The author criticized his contemporaries50 who assumed that literature and staging existed separately, “[...] although theater is, or can be, both literature and staging, not one at the expense of the other, but one because of the other” (Williams, 2010, p 38). In this study, therefore, we analyzed the text of the operetta as a text written to be staged. Moreover, to analyze the education that took place during the performances, we considered the circumstances of production and presentation of the shows, and the sensibilities involved.

We started from the theatrical text and crossed data with information about the stagings51 and about the sociocultural and sensitive dimension of that context. Data were found in the critiques and news posted in local newspapers; data related to the context of the play Santo Antônio nas Águas, from São João del-Rei, were found in studies about said city in that period, about the history of theater, the history of women, the history of the body, and about the history of the Brazilian army. When addressing some scenes from different aspects and considering the subjects involved in the presentations and their sensibilities, we sought to describe some sensations and feelings that would have possibly affected the viewers.

A mulher soldado em cena tensionando sensibilidades hegemônicas e provocando sensações e sentimentos diversos

The narrative structure of the studied operetta tensioned the hegemonic sensibilities of São João del-Rei society, causing different sensations and feelings, which would possibly have affected the viewers. Analyzing the plot of the operetta in the set of works staged by the dramatic club, we saw some similarities between them. Such similarities are not random, they are related to the motivations that led São João del-Rei’s amateurs to choose them: the group’s material and artistic possibilities, and the ability of the plots to dialogue and provide pleasure to the local audience, that is, the poetic potential of the plays.

A similar element among the operettas staged by the amateurs that certainly contributed to establishing an immediate empathy with São João del-Rei’s audience is the environment in which the narratives unfolded52. In a city where people had been living for some time with corporations of the Brazilian army, the population would possibly see themselves, and/or their children and husbands, on stage. Of the five shows in which the operetta A mulher soldado was staged, two honored servicemen, the club’s president, Captain José Pimentel, and General Napoleão Felipe Achê, from Niterói53. A ‘military operetta’ that took place in a barracks would be ideal for the occasion.

Another similarity observed is the narrative structure of the operettas, which is inspired by the formula for ‘well-made plays’ defended by the important French critic Sarcey and appreciated by Artur Azevedo. ‘Well-made plays’, a standard created by Scribe, characterized a large part of the French dramaturgy, of light genres, produced at the Belle Époque. According to Flores (2008), Scribe developed a dramatic-writing formula that met the demands for expansion of ‘theater as entertainment’. Such expansion was the result of the influences of an industrial world in which dramatic production aimed at the market, for commercialization, was growing.

Flores (2008) states that Scribe’s invention would have enabled the promotion of a theatrical market, in which the profession of dramatic writer became well paid. The formula for ‘well-made plays’ focused on the effects of dramaturgy on the audience and was based “[...] on feelings that everyone understands and that interests everyone because they are the feelings common to human nature; it is clearly exposed, develops logically and has a happy outcome” (Carlson, 1997, p. 277)54. Thus, analyzing the play in view of this formula brings us closer to the sensations and sensibilities involved at the time of the performance.

According to Flores (2008, p. 27), ‘well-made plays’ have a “[...] quite fixed structure from beginning to end: presentation of the problem, development of the latter, climax and resolution”. The analyzed operetta distributes these stages into three acts, presenting the problem in the first, the development in the second, and the climax and resolution in the third and last acts. Thus distributed, the narrative unfolds around the problem, and the dramatic actions are logically linked, making it increasingly complex. This way, the tension gradually rises and exposes latent conflicts. The culmination of the problem is also the moment when all conflicts generated throughout the narrative are resolved.

Although the staged operetta was written by French authors in a context different from the one studied, we can say that the problem tensioned by the play with the aim of involving the audience is indicative of the feelings and sensibilities of the people involved with the shows that took place in São João del-Rei (1916), as staging gave way to performance. It is then up to us to analyze the elements that generated tensions in the course of the narrative, with the aim of perceiving what sensations they caused in São João del-Rei’s audience.

In the operetta A mulher soldado, the problem is partly caused by a misunderstanding. Sergeant Gabriel, married to Clarinha, consented to have Alice visiting the barracks and was anxiously awaiting her, as he wished to distract himself a little. The woman he was waiting for was “[...] a single-boy win [...]” (p. 9)55, who he had met when he took his wife to the seamstress (coincidentally, the seamstress was Alice). She went to the barracks without knowing that Gabriel was married. The misunderstanding begins when Sergeant Villar and the Captain assume that Alice was Gabriel’s legitimate wife. The situation grows more complicated with each scene: a not-so-clear conversation with Villar becomes true for the Captain and spreads among all soldiers and officers. Clarinha, the true, legitimate wife, arrives at the barracks to visit her husband and learns from Villar (who assumes she is Gabriel’s mistress), that he was not available, as he was visiting the barracks accompanied by his ‘legitimate wife’, Alice. Clarinha, to take revenge on her husband, disguises herself as a soldier and takes the place of reservist Ventura. Thus, the problem that sews all the dramatic action is presented in the first act: the presence of a woman, disguised as a soldier, in the barracks.

In the second act, the tension around the presence of a woman in a masculine environment, being seen and treated as a man, involves the audience and intensifies as Clarinha faces common situations for a reservist, but which, for a lady, could be considered inappropriate. The performance, as poetic communication, took place during these shows, because the sensations that the dramatic action provoked dialogued with the audience’s sensibilities, in order to evidence and cause conflicts related to the way those people made sense out of what it meant to be a man and to be a woman, how they experienced sexuality, and their ways of thinking about the relationship between men and women.

Sharing the room and the bed with reservist Thomé was one of the complicated situations that Clarinha faced, exposed during much of the second act. Thomé acted as usual, undressing before going to bed. As it was very cold, he proposed to share the bed with his mate, but Clarinha refused. The reservist found very odd that the ‘boy’ was embarrassed to see him taking off his clothes, in addition to not understanding his stubbornness, as he preferred to die of cold and the discomfort of sleeping, dressed, in the chair.

What sensations could such a scene cause in São João del-Rei’s audience in that period? The situation, even today, would cause some embarrassment to the woman who was dressed as a soldier. We know that, with regard to sensibilities, ruptures occur in the long run and that, when investigating a historical period that is only a century away from us, we risk committing anachronisms. According to Pesavento (2007, p. 15),

Sensibilities are subtle, hard to capture, as they are inscribed under the sign of otherness, translating emotions, feelings and values that are no longer ours. More than other issues to be looked for in the past, they evidence that the work of history always involves a difference in time, a foreignness in relation to what happened from outside the experience lived. And the latter, in this case, places the concept of sensibilities under the sign of otherness, without which it is not possible to redefine the past, an indispensable goal of the historian, as Paul Ricoeur points out.

We must then ask ourselves: what is the intensity and meaning of the tension generated by the scene in question in São João del-Rei’s 1916 audience? What relationship did the women and men of the time have with their own bodies? What did female nudity and male nudity represent? What meanings involved the coexistence of bodies of opposite sexes in the same environment? What were the limits of looking, smelling, touching the other?

São João del-Rei’s elite were living, during the first decades of the 20th century, in between devotion to the Catholic Church and the desire for progress and for civilization. As we have already mentioned, the attention of those people was turned to new ideas, new habits, techniques, technologies and products coming from Rio de Janeiro and Paris, at the same time that they strongly preserved Catholic customs and rituals. We find traces of this duality experienced by the city’s elite in the vaudeville written in 1911 by Severiano de Resende, from São João del-Rei. The narrative takes place in a seaside resort and around the belief that would explain the miraculous properties of its waters. Located in the territory of the municipality of Tiradentes, next to São João del-Rei, the resort also received the elite of the period for their tours and delights in the country life. In the vaudeville Santo Antônio nas Águas56, there are two emblematic characters: Dr. Polybio and Father Zuquim. The former had just arrived from Paris and was amazed at the city, ‘light of civilization and progress’, ‘dazzling center’, ‘capital of the intellectual universe’. According to Polybio, the lights of Paris had not yet arrived in São João del-Rei, “[...] in this land, one vegetates [...] great is nature, the haughty mountains, the superb rivers [... ] The small, Lilliputian57 man, the moral horizons limited for the flights of talent; the spirit suffocates and struggles in a cramped space. On ne vive pas [...]”. The commander, a third character, rebukes Polybio for that nonsense and for his contempt for the things of ‘our land’. For him, young people like Polybio showed themselves as “[...] propagandists of the most subversive and disparate doctrines”. Father Zuquim, however, is succinct and far more radical than the commander; for him, Paris is the ‘land of damnation’, the ‘modern Gomorrah’. Standing before the picture painted by São João del-Rei’s vaudeville, we can state that the elite lived this duality and that, certainly, people had opinions that varied on a scale ranging from Polybio’s fascination to Father Zuquim’s radicalism.

This reflection helps us imagine the place, or the repercussion, in Minas Gerais’s city, of some transformations that occurred in relation to the sensibilities of Parisians. According to Sohn (2008), during the 20th century, France experienced a progressive retreat of decency. Previously seen as a virtue advised to girls and young lady, the meaning of decency is transformed at the Belle Époque. Such a transformation is accelerated in the interwar period with the overcoming of secular traditions, such as interdictions against women showing their bodies and curves, the habit of going to the toilet without undressing, and concerning the relationship of couples with sex and sexuality. Sohn (2008, p. 110, author’s emphasis) states that “[...] at the end of the 19th century, love is still made with the couple ‘totally naked, only with a nightgown on’, and the chamber is an enemy of light’. These prohibitions refer to a Christian conception of sexuality, circumscribed to legitimate couples, essentially meant for reproduction and an enemy of lust”.

It is plausible to imagine that São João del-Rei’s couples had different ways of having sexual relations, which depended on their involvement with religion and the complicity relationship they built between themselves, since the obstacles to the fulfilment of sexual desires, in this case, were only the judgment from God and from the spouse. These nuances arise from the gradual decay of arranged marriages and the valuation of marrying for love.58 At the beginning of the 20th century, there were also changes in relation to the exposure of bodies in public spaces. According to Sohn (2008), the body begins to be exposed ‘under the combined effect of fashion and seaside-resort tourism’; in 1900, aquatic competitions also contributed to this process.

Bathing suits, such as those from Rio and Paris, possibly allowed “[...] associating sea bathing and decency” (Sohn, 2008, p 110); in the case of São João del-Rei, bathing in Águas Santas [Saint Waters] was associated with decency. Thus, the nakedness of a woman before her husband was no longer unthinkable for São João del-Rei’s audience. However, the exposure of the woman’s body to a stranger certainly was. In the case of the operetta A mulher soldado, Clarinha’s nakedness before Thomé also meant the revelation of the female soldier’s disguise, her having to face the consequences of that in accordance with the rules of the barracks, and the end of the protagonist’s revenge.

We could ask ourselves: why would Clarinha’s disguise be configured as the revenge of a betrayed woman? Would the protagonist not be penalizing herself by going through the experience of serving the army? In what sense, or how, would this affect her husband Gabriel? What did the presence of a woman in the barracks mean for the people in that context?

At the end of the second act, Gabriel hears the argument between Thomé and Clarinha, realizes that she was in the next room and goes meet her with the intention of convincing her to end the dissimulation. He dismisses Thomé in order to have a private conversation with Clarinha:

Gabriel

Clarinha, we need to end this. I cannot suffer these embarrassments anymore.

Clarinha

So do not suffer; I am not the one to blame.

[...]

Gabriel

But can you not see that they will find out that you are a woman anytime?

Clarinha

[In pencil, by the side: Then let them fin...

Do not bother yourself. I have someone to defend me if necessary (p. 36-37).59

It is evident that Gabriel’s concern is not about his wife’s integrity, or about the problems she was facing as a reservist. The sergeant was concerned only about his own ‘honor’. Gabriel says he can no longer suffer those ‘embarrassments’. The sergeant was therefore the victim of the story, he was being molested and could have his wife found dressed as a soldier in the barracks. Clarinha shows she did not care about the revelation of her disguise - “Then let them find out!” -, she is aware that her husband would be the most affected in that situation and, in order to carry out her revenge, she seems to wish to have her identity revealed. Why was Gabriel so ashamed of that situation? Why did this idea make sense to São João del-Rei’s audience? What sensibilities were involved in that plot?

In the second half of the 19th century, in order to awaken patriotism among Brazilians, biographies of national ‘heroes’ and ‘heroines’60 were written. Among the ‘heroines’, two stood out in those publications for fighting for the nation, disguised as soldiers. The first, Maria Quitéria, introduced herself as Private Medeiros and fought battles for Brazil’s independence. After her disguise was discovered, she was personally awarded by the Emperor in 1823. Antonia Alves Feitosa, known as Jovita Feitosa, dressed as a man and volunteered to fight in the Paraguayan war; she was quickly caught and, according to Wolff (2013, p. 429), “[...] instead of being immediately discarded, she became a national curiosity, traveling across several states, calling on men to volunteer. She was even promoted to sergeant”.

Although both women had personal reasons for volunteering in the wars, Maria Quitéria61 and Jovita Feitosa62 were praised, and their attitudes were used as an example of courage and love for the country, and as an encouragement for men to do the same, although not all approve the presence of women in the barracks. Machado de Assis published in Diário do Rio de Janeiro, on February 7, 1865, a long article dedicated to “[...] demarcating women’s space of action during a war: praying, caring for the wounded, sewing for the soldiers” (Prado & Franco, 2013, p. 201). Wolff (2013) adds that Jovita’s story sparked great controversy in the press of the time. The author mentions a publication in Jornal do Commercio, from 1865, stating that the presence of the young lady in the army was a grave insult against the dignity of men. According to Wolff (2013, p. 430, author’s emphasis), they wore a petticoat over the uniform, which, for the author, made it clear “[...] that the army would not be an ideal place for women, and that these ‘female soldiers’ were exceptions”.

In the second half of the 19th century, women accompanied the troops, following their children and/or husbands and fulfilling the roles underlined by Machado de Assis. They took care of supplies, prepared food, sewed, did laundry and cared for the wounded and sick. When the operetta A mulher soldado was staged in São João del-Rei (1916), women had already been removed from the barracks through reforms carried out in the Army. They no longer performed tasks assigned to their sex, let alone being soldiers. The possibilities for women to enlist in the guise of men became null after the mandatory medical examination was instituted before the engagement of the soldier. Their presence was only tolerated when they were wives of soldiers or of officers (Wolff, 2013).

During that period, although the focus was more on the First World War than on the Contestado conflict, there was some news about the ‘virgins’, women who followed the leader of the rebels (the monk José Maria, killed in the first battle) and claimed they had visions of their deceased leader, moments when they received instructions on how to proceed in the fight. Teodora and Maria Rosa led the rebels for a while through these visions. Since the Army’s unit, based in São João del-Rei, was in that war between 1914 and 1915, stories about the female warriors of the Contestado possibly circulated. But those ladies were seen, along with the rebels they led, as fanatic, ignorant, mere country women.63

It is also important to consider the women’s struggle for rights that were growing intense in the first decades of the 20th century, generating strong reactions, such as criticisms expressed in plays, cartoons and in the press. According to Rachel Soihet (2013), middle-class and upper-bourgeois women claimed their right to professional training and paid work, full access to quality education, the right to vote and to eligibility, considered essential for them to achieve other goals. Women’s struggle was gaining strength since the proclamation of the Republic. Although the Constitution was enacted in 1891 without affirming women’s right to vote, the theme was discussed in the Constituent Assembly and remained on the agenda of intellectuals and of the press. Soihet (2013) recalls that the opposition to women’s suffrage was founded on the ‘scientific’ argument of the fragility of women, their limited intelligence, their inadequacy to perform public activities. Women should take care of their families.

In the vaudeville Santo Antônio nas Águas, already mentioned, it is evident that the debate on women’s demands was, in some way, present in the city. The characters, commander, Doctor Polybio and Thomazinho, talk about the quality of the telegraph service:

Dr. Polybio

Just as what happened with me a little while ago on a trip to Belo Horizonte. I telegraphed from Lafaiete to my friends, informing them of my arrival, that is, at 6:30, so that they waited for me with the lunch. I arrived in the capital of Minas Gerais at 10:00, and only when I was having dinner at 6:00 they came to bring the telegraphic dispatch. In Paris indeed electricity is the electric city.

Thomazinho

This service is all messed up around here.

Commander

The telegrams are all delivered late and at bad times, when they do not come all damaged.

Dr. Polybio

So in Rio you have quite funny puns. Incroyable.

Commander

Effect of feminist conquests; ever since they put women in telegraphs and post offices, communications are all messed up; all men have shaved their beards and mustaches, now they wrap themselves around women’s arms, when they should be serving them as points of support, while they, the women, wear pants. Men turning into women, and women turning into men. Super modern.64

Given her commander friend’s comment, Helena, who up until then was only listening, protested, and Geni added:

Helena

I disagree. Women do the job very well.

Geni

And with great diligence.

Dr. Polybio

Women. New ideas emancipate them and give them access to the noblest roles. In Paris, women are taking up all positions: - Le monde marche.65

The conversation then takes a different turn and leaves hanging in the air the words of Dr. Polybio, a young, educated man who had just returned from Paris. The author of the vaudeville seems to represent some of São João del-Rei people’s stances on feminist conquests and the ‘super modern’ changes that society was going through at that time. Such stances ranged from opposition to the changes that were taking place and the fear around the reversal of the social roles of men and women, to people who bet on development, on the progress inspired by the ‘civilized’ Paris, where women already occupied noble positions. The characters Helena and Geni, though timidly, took a stand in defense of the conquests of the feminist movement.

Given this panorama, we can imagine the numerous sensations that the staging of a woman in the barracks, disguised as a soldier, could cause in São João del-Rei’s audience. In scene 4 of the second act, which we began to describe above, when Gabriel asks Clarinha to end her revenge, he is furious with her negative response, with the ‘boldness’ of his wife in making it clear that he knew he would be the most affected by all that story, and by implying that he did not care. So Gabriel reacts as follows:

Gabriel

(furious) Clarinha! Clarinha! I’m your husband. I have not yet waived my rights.

Clarinha

Your rights? Your rights are the same as mine. You do what you please, is it not so? I also have the same right, I give like for like. [Line changed by Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo]

Your rights are the same as mine. You have a mistress, right? Well, I want to have a lover as well. I am doing just as you do. [Original line in the manuscript].66

Gabriel

(advances towards Clarinha) Do not insult me! Look [...] (grab her by the arm)

Clarinha

(screaming)

Let me go! Let me go!

Villar

(wakes up) One cannot sleep! What a hell!

Gabriel

(furious) Do you want to drive me crazy? Do you want to make a scene? (p. 36-37).67

The couple arguing about the rights of a husband and a wife certainly led São João del-Rei’s audience to think about the discussions around women’s demands that were happening in that period. Gabriel demanded his rights from his wife Clarinha, expressed in the idea of obedience. Although some men and women disagreed that the latter should be subservient to their husbands, the sergeant’s attitude made perfect sense in that context. According to Cortês (2013), the Civil Code enacted in January 1916 continued to treat married women as ‘relatively incapable’ inferior beings, who should live under the protection of their husbands, the ‘heads of the marital society’, responsible for determining the fates of their wives and their whole family.

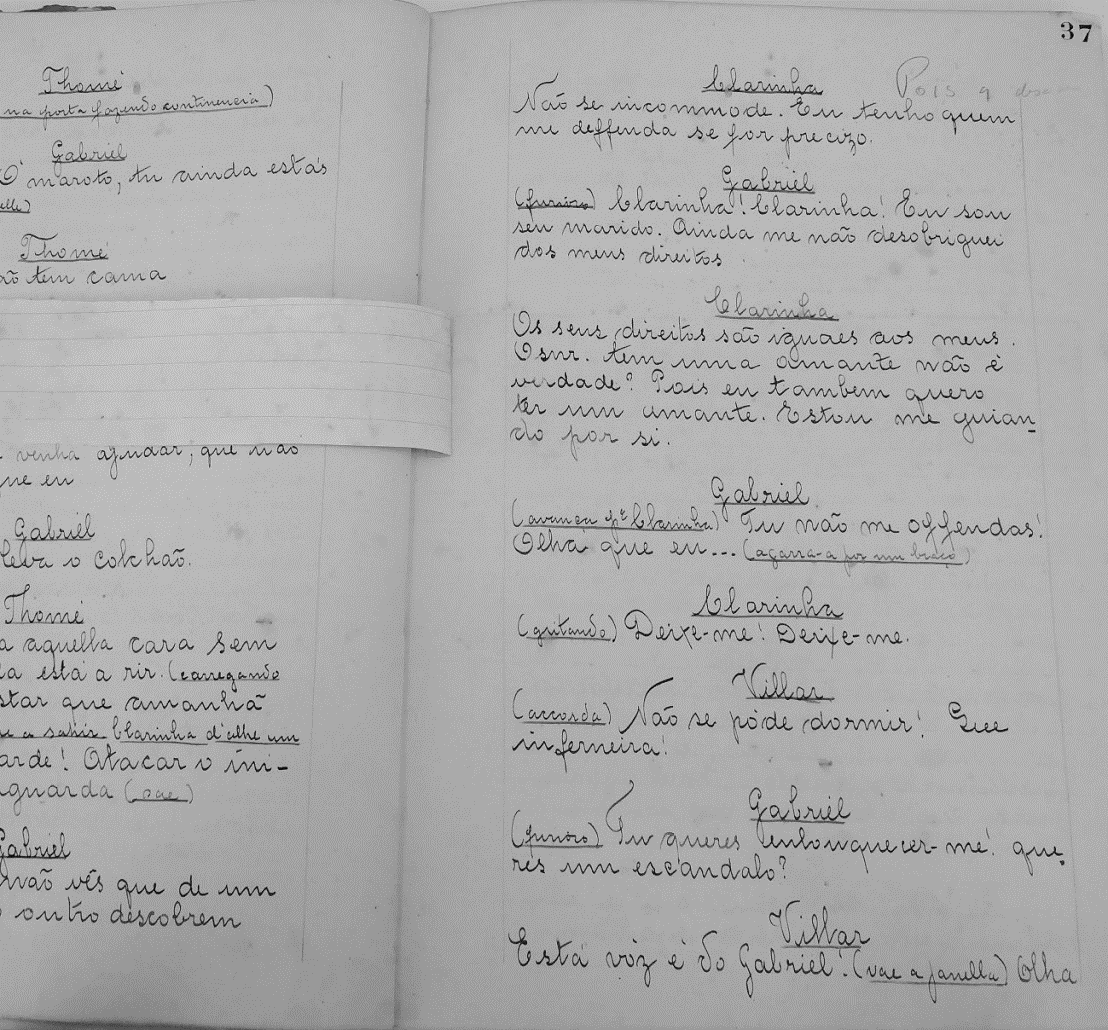

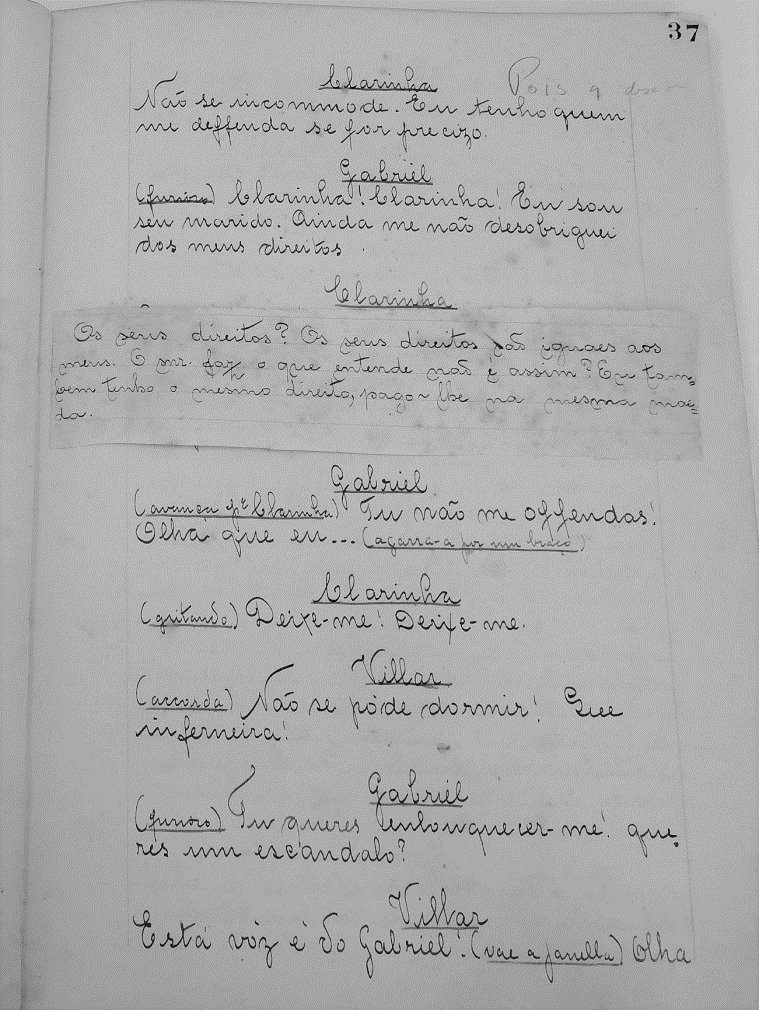

It is interesting to note, as we can see in Figures 1 and Figures 2, that Clarinha’s line, in the original manuscript of the operetta, was changed. In the original text, Clarinha said that she had the same rights as those of her husband and that, therefore, if he had a lover, she also wanted to be entitled to that. Although laws were stricter for women, adultery was condemned for both sexes legally68 and by the Catholic Church. Thus, this element was removed from the protagonist’s line. It would not be advisable for an elite said to be virtuous and civilized to go against both institutions (State and Church) so forcefully. However, even with the change, the demand for equal rights is not erased. Clarinha’s new line is open to interpretation, to the viewer’s liking: “Your rights? Your rights are the same as mine. You do what you please, is it not so? I also have the same right, I give like for like “(p. 36-37).69

Source: Handwritten copy of the operetta A mulher soldado, GPAC archive - UFSJ (p. 37)

Figure 1 Original line from the operetta manuscript.

Source: Handwritten copy of the operetta A mulher soldado, GPAC archive - UFSJ (p. 37).

Figure 2 Changed line.

Feeling insulted by Clarinha, Gabriel returns the insult by responding to his friend Villar, who came closer, attracted by the noise the couple was making during the argument.

Villar

Are you not done yet? Do you want to force her to say that she is your wife?

Gabriel

(Ironically) No, this lady is not my wife. She is [...] my mistress.

(Thomé enters) Are you satisfied?

Clarinha

Despicable! (slaps him) (p. 37-38).70

The man felt insulted by his wife demanding to have the same rights as his, just as that woman felt insulted by being put in the position of a mistress. Thomé witnesses the aggression against Sergeant Gabriel and calls the soldiers to arrest the reservist who perpetrated the wrongdoing. Clarinha, then, is arrested.

In the third act, the climax comes with the arrest of Clarinha, who, disguised as a soldier, was sentenced to be shot for assaulting a sergeant. Thomé, Gabriel and Villar were nervous about making Clarinha’s escape possible. The former due to guilt (as he was the whistleblower of his fellow reservist), and the other two for knowing about Clarinha’s disguise. Thomé stands guard at the prison door where she was. Sorry for having put Ventura/Clarinha in that situation, Thomé decides to help him/her run away. He gets a dress from the innkeeper so that his mate can escape in the guise of a woman. Gabriel and Villar arrive before Thomé’s plan comes to fruition and chase him out. He, in order not to see his plan failed, resists leaving the watchman post, but ends up following the orders of the two sergeants, who find Clarinha dressed as a woman and understand Thomé’s insistence on remaining on guard. As soon as Clarinha turns away, the real Ventura appears to take back his uniform from Sergeant Villar. Gabriel and Villar give the uniform to the reservist and arrest him in Clarinha’s place.

The captain receives the report that there is a woman dressed as a military man, and Clarinha is prevented from leaving the barracks. The captain decides to interrogate prisoner Ventura, accused of being a woman disguised as a soldier, then interrogates Clarinha, accused of being a soldier dressed as a lady. The whole situation is revealed, and Sergeant Gabriel is forgiven by the captain. Clarinha, as a reservist, complies with the captain’s orders to forgive her husband. This was a servicemen virtue that suited women, that of obedience to superiors.

We assume that, composing the audience that was watching the operetta staged by Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, there were middle-class and elite women who, despite having a behavior consistent with a very religious society, as São João del-Rei’s women were, appreciated the French ‘advances’ and, at least, were sympathetic to the demands of the feminist movement, such as Helena and Geni (characters in Severiano de Resende’s vaudeville, from São João del-Rei). Those women were possibly thrilled with Clarinha’s revenge and, certainly, felt avenged through the protagonist’s attitude in disguising herself as a soldier and serving in the barracks where her husband was a sergeant. Those were ways of ‘insulting the dignity’ of military men: wearing pants, riding horses, facing, without being caught, the same situations that a reservist faced, proving themselves as capable as a man, demanding equal rights. That night, watching the operetta, we can imagine that they sat upright, their lungs filled with air, their eyes smiled, they felt the pleasure of being, for a moment, Clarinhas, Marias Quitérias and Jovitas, they felt the pleasure of being in charge of the situation. Such sensations may have been elaborated in innumerable ways by each one of the female spectators, constituting feelings, values and sensibilities. It would be impossible to say for sure what sensibilities those women learned or elaborated that night, also because this is a process that develops in the long run and not just in a single event, but we can imagine that, by experiencing the pleasure of feeling as strong and capable as the heroines mentioned, they took a liking to the sensation, which may have been the engine of personal transformations and, who knows, of social transformations.

As for the men who, just as Polybio (a character in São João del-Rei’s vaudeville), believed that feminist conquests were part of the development and progress of society, possibly laughed at themselves, judging as ridiculous the attitudes of characters like Villar, who subjugated women, feeling in control of the situation when he said he had won Clarinha on the tram. Men like Polybio saw, in the situation in which a woman was not noticed among the soldiers, the confirmation of their convictions, the proof that they were, indeed, capable of doing activities performed by men.

On the other hand, the men who, just as the commander (also a character in Severiano de Resende’s vaudeville), believed that women were fragile, lacking in intelligence, and that their duty was to take care of the family, possibly squirmed in their seats, uncomfortable with the fact that, in that barracks, no one noticed the presence of a woman. Thomé, who spent a long time so close to Clarinha, proved incapable, for not even imagining that he was before a lady, even when he saw her dressed as a woman, at the end of the third act. It is certain that, because he is a simple, uneducated man, this image would be disconnected from that of cultured and educated men.

The scene that exposes the captain’s stubbornness in obtaining from Ventura (dressed as a soldier) a confession that he was a woman and even firmly stating that Clarinha was a man, when she was already wearing skirts, would possibly provoke a nervous laugh and blush the faces of those who were certain of the inadequacy and inability of women to take on these traditionally masculine positions and roles. However, a trait of the character Ventura justified the Captain’s confusion, who could not be demoralized on stage, by a club led by a captain, while performing to an audience composed of servicemen as well. Ventura was an effeminate man.

At the end of the first act, Ventura goes after Sergeant Villar to have his uniform back. The text of the operetta provides the following indication for the moment when he introduces himself to the sergeants: “Ventura - I am a pastry chef, and my name is Ventura de Sá. (with effeminate manners)” (p. 21, 1st act, scene XI).71 When accused of being a woman, in the third act, Ventura defends himself: “On appearances, do not judge me / I give you my word of honor that I am a man” (p. 46, 3rd act, scene VI).72

The local press praised the interpretation of the character Ventura by the amateur actor Humberto Preda. He would have gotten “[...] good laughs from the audience” (O Theatro, p. 28). According to an anonymous author who had his text published in the periodical O Zuavo(p. 34, author’s emphasis): “His effeminate manners, his walk, his mellow voice, his well-studied swaying also, at first, left me confused as to the actual sex he has! Very well!”. The author of this text corroborated the perception of the servicemen on stage, who accused Ventura of being a woman, attributing perfection to the amateur’s performance. At the same time, he released the captain from the ridicule situation of not being able to tell a man and a woman apart. The comicalness given to the character Ventura ridiculed his effeminate character and left the captain’s reputation untouched, with the captain having reason to be confused about Ventura’s sex.

The men in the audience, who believed that women were inferior beings, possibly returned to their homes satisfied and convinced of their ideas. At the end of the operetta, everything returned to its ‘due place’, with Clarinha’s obedience and her forgiveness granted to Gabriel.

In their turn, those women who believed in their fragile nature and in their inadequacy for spaces and roles deemed masculine, were possibly apprehensive while watching scenes that showed the situations that Clarinha had to face as a reservist. They feared for the integrity of the protagonist, judged her careless attitude and were thrilled with the happy ending in which Clarinha followed the captain’s orders to forgive her husband Gabriel. It is clear that those men and women are models that help us perceive possible sensations and feelings generated in the staging of the operetta A mulher soldado and, as models, they simplify reality, which, certainly, is much more complex. We do not intend to state that these people existed just as we described them, but the models imagined here were built from data on the men and women of that society, in that period; therefore, they are instruments that helped us bring ourselves closer to the investigated reality.

Further Considerations

The analysis developed in the present article reveals that the narrative structure of the operetta A mulher soldado, consistent with the formula for ‘well-made plays’, provoked effects in the audience, reinforcing hegemonic sensibilities, at the same time that it allowed different sensations and feelings that were even opposed to those legitimated by the dominant elite. The outcome of the plot indicates which were, for the members of Club Dramático’s board, the feelings that ‘everyone would understand’, common to all of São João del-Rei people who potentially frequented playhouses. Hegemonic sensibilities become evident, those that, from the power relations established in that society, sought to silence other sensibilities (collective and individual).

The betrayed wife’s anger, to some extent, is understood and legitimized, as Clarinha is not punished for her disguise. But it is not up to her to question the order to forgive her husband. Obedience, the feeling of subalternity to a military captain, is highlighted, but the woman’s feeling of subalternity before other men and even her adulterous husband is also exposed and valued.

In the scene in which the captain interrogates Clarinha and Ventura in order to check the report that there was a woman in the barracks, who would be dressed as a soldier, women’s feeling of fragility, inadequacy, inability to have a post in the army is reinforced. However, these feelings are not only directed towards women, but also towards femininity, the feminine way of being that is judged as inappropriate. ‘Effeminate’ men like Ventura should feel as fragile, inadequate and incapable as women.

However, the narrative structure of the operetta, by tensioning these sensibilities throughout the play, ends up enabling the construction of other modes of feeling, other modes of responding to the tensions exposed on stage. Each subject present in the performances was probably affected differently, depending on their social place, their previous experiences, their individual and collective sensibilities. Given the impossibility of investigating specific subjects and how they felt during the stagings, we created possible models of viewers from studying the issues that were addressed on stage, with regard to the historical, social and cultural context of the presentations.

It was possible to infer that the audience comprised a diversity of subjects who thought and felt differently. There were white and black men and women who took a stand on gender relations, more supportive of women’s emancipation, together with men and women who believed in the distinctions that put men in a place of authority, and women in a place of subalternity.

Sergeant Gabriel’s reaction to his wife disguised as a soldier reinforced sensibilities linked to the gender relations by which women should feel inferior, unable to make choices, incapable in relation to men. On the other hand, the disguise evidenced a daring wife who questioned her husband’s authority, who should be ashamed. The fact that the disguise was not noticed by the servicemen worsened the situation.

Thus, as the play tensioned the husband’s authority, it also exposed a woman who thought for herself, who made decisions in accordance with her judgments and desires, and who, for a long time, had her plans successful. Clarinha proves to be perspicacious in choosing to take revenge in a way that weakened her husband, brave when facing Gabriel to the point of slapping him, and able to stand the adversities imposed on the reservists of that detachment.

On the one hand, the men and women who defended men’s place of domination felt uncomfortable with the situation in which Gabriel found himself, and related to his feeling of shame, anger and fear. On the other hand, the men and women who supported women’s fight for emancipation felt hopeful, capable of facing men’s domination.

Finally, we can state that the results of this study contribute to understanding the education of sensibilities as a complex, dialogical and plural phenomenon. The study highlights the various possible responses and modes of feeling that were constituted in one same moment (during the theatrical performances) from the experiences of each subject present. These experiences are related to how those particular subjects related to the historical, social and cultural context in which they were inserted. This work also contributes to the field of history of education, shedding light on other possibilities of approaching educational phenomena, joining the movement within the field of broadening study objects, research sources and data analysis methods.

REFERENCES

Adão, K. S., Lima, A. W., Campos, A. E. D., & Silva, T. J. B. (2009). O futebol em São João del-Rei: apontamentos acerca de sua história (1907 a 1944). In Anais do 11º Congresso Nacional de História do Esporte, Educação Física, Lazer e Dança (p. 11-26). Viçosa, MG. [ Links ]

Brasil. Câmara dos Deputados. (1916, 5 de janeiro). Lei nº 3.071, de 1 de janeiro de 1916. Código Civil dos Estados Unidos do Brasil. Diário Oficial da União. Seção 1, p. 133. [ Links ]

Carlson, M. (1997). Teorias do teatro: estudo histórico-crítico, dos gregos à atualidade (G. C. C. Souza, trad.).São Paulo, SP: Fundação Editora da UNESP. [ Links ]

Cortês, I. R. (2013). Direito: a trilha legislativa da mulher. In C. B. Pinsky & J. M. Pedro. Nova história das mulheres no Brasil (p. 260-285). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Couto, E. F., & Barros, A. A. (2011). Futebol e modernidade em São João del-Rei/MG: o caso do Athletic Club (1909-1916). In: Anais do 26º Simpósio Nacional de História - ANPUH (p. 1-13). São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

Flores, F. T. (2008). Nem só bem-feitas, nem tão melodramáticas: The children’s hour e the little foxes, de Lillian Hellman (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Guerra, A. (1968). Pequena história de teatro, circo, música e variedades em São João del- Rei (1717-1967). Juiz de Fora, MG: Esdeva. [ Links ]

Guilarduci, C. J. (2009). A cidade de São João del-Rei nas entrelinhas dos manuscritos do teatro de revista na Belle Époque: um testemunho da história cultural são-joanense (Tese de Doutorado). Centro de Letras e Artes, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Houaiss, A., & Villar, M. S. (2009). Dicionário Houaiss de língua portuguesa. (Elaborado pelo Instituto Antônio Houaiss de Lexicografia e Banco de Dados da Língua Portuguesa S/C Ltda). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Objetiva. [ Links ]

Lima, M. T. G. A. (2006). O teatro amador nos álbuns de Antônio Guerra (Dissertação de Mestrado). Departamento de Letras Artes e Cultura. Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei, São João del-Rei. [ Links ]

Mccann, F. D. (2009). Soldados da pátria: história do Exército Brasileiro (L. T. Motta, trad.). São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Oliveira, M. A. T. (2018). Educação dos sentidos e das sensibilidades: entre a moda acadêmica e a possibilidade de renovação no âmbito das pesquisas em História da Educação. História da Educação, 22(55), 116-133. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.1590/2236-3459/76625 [ Links ]

Pesavento, S. J. (2007). Sensibilidades: escrita e leitura da alma. In S. J. Pesavento & F. Langue (Orgs.), Sensibilidades na história: memórias singulares e identidades sociais (p. 9-21). Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS. [ Links ]

Pineau, P. (2018). Historiografia educativa sobre estéticas e sensibilidades na América Latina: um balanço (que se tem conhecimento) incompleto. Revista Brasileira De História Da Educação, 18, e023. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v18.2018.e023 [ Links ]

Prado, M. L., & Franco, S. S. (2013). Cultura e política: participação feminina no debate público brasileiro. In C. B. Pinsky & J. M. Pedro. Nova história das mulheres no Brasil (p. 218-237). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Rocha Junior, A. F. (2006). Arquivos teatrais: letra e voz. In: Anais do 4º Congresso de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Artes Cênicas (Memória ABRACE X) (p. 71-72), Rio de Janeiro, RJ. [ Links ]

Sá, C. M. (2015). Do convento ao quartel: a educação das sensibilidades nos espetáculos teatrais realizados pelo Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, em São João del Rei MG (1915-1916) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte. [ Links ]

Sadi, R. S., & Adão, K. S. (Orgs.). (2011). Lazer em São João del-Rei: aspectos históricos, conceituais e políticos. São João del-Rei, MG: Ed. UFSJ. [ Links ]

Soihet, R. (2013). Movimento de mulheres: a conquista do espaço público. In C. B. Pinsky & J. M. Pedro. Nova história das mulheres no Brasil (p. 218-237). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Sohn, A-M. (2008). O corpo sexuado. In A. Corbin, J-J. Courtine & G. Vigarello. História do corpo: as mutações do olhar: o século XX (p. 109-154). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

O Theatro. (1916, 13 de julho). Álbum 13, p. 28. [ Links ]

Vapereau, G. (1893). Dictionnaire universel des contemporains: contenant toutes les personnes notables de la France et des pays étrangers. Paris, FR: Ed. L. Hachette. Recuperado de: http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb31542988d. [ Links ]

Williams, R. (2010). Drama em cena (R. Betonni, trad.). São Paulo, SP: Cosac Naify. [ Links ]

Wolff, C. S. (2013). Em armas: Amazonas, soldadas, sertanejas, guerrilheiras. In C. B. Pinsky & , J. M. Pedro. Nova história das mulheres no Brasil (p. 218-237). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Yon, J-C. (2000). Jacques Offenbach (Coleção Biographies). Paris, FR: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Yon, J-C. (2012). Une histoire du théâtre à Paris: de la révolution à la grande guerre. Paris, FR: Ed. Flammarion. [ Links ]

O Zuavo. (1916, 25 de setembro). Álbum 13, p. 34. [ Links ]

Zumthor, P. (2007). Performance, recepção, leitura. São Paulo, SP: Cosac Naify [ Links ]

37It is the doctoral thesis entitled From the Convent to the Barracks: The Education of Sensibilities in Theater Performances Held by Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, in São João del-Rei - MG (1915-1916) [Do convento ao quartel: a educação das sensibilidades nos espetáculos teatrais realizados pelo Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, em São João del-Rei - MG (1915-1916)], developed by Carolina Mafra de Sá, under the supervision of Professor Ana Maria de Oliveira Galvão. The research was funded by the Capes, and so was the sandwich PhD at Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense, which was of great importance for the development of the research.

38“Si bien huellas de estos temas son rastreables en trabajos previos - por ejemplo, en historias que se ocupan de la infancia, del currículum, e de la formación docente - los efectos del llamado ‘giro afectivo’ (Lara & Enciso Domínguez, 2013; Macon & Solana, 2015) de los últimos tempos permitieron nuevos recortes y profundizaciones mediante la construcción de abordajes específicos. Este ‘giro’ temático de las ciencias sociales - con especial mención del impulso liderado por la antropología - supuso un cambio em la producción de conocimiento sobre tópicos tales como los afectos, la sensibilidad, las emociones y los gustos, principalmente reconociendo su variabilidad cultural e histórica (Lutz & White, 1986)”.

39For more information on São João Del-Rei at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, see Guilarduci (2009).

40For more information, see Adão, Lima, Campos and Silva (2009), Couto and Barros (2011), Sadi and Adão (2011).

41For more information, see Guerra (1968).

42For more information on Club Dramático Arthur Azevedo, its members and its repertoire, see Sá (2015).

44 Pesavento (2007, p. 14-15) defines sensibilities as “[...] imaginary operations of sensemaking and representation of the world, which manage to make an absence present and produce, by the power of thought, a sensitive experience of the event”.

46For more details on the constitution of this archive, and for an in-depth analysis of the materiality of the albums, see Lima (2006), who studied amateur theater in the early 20th century, in the state of Minas Gerais, resorting to the albums made by Antônio Guerra.

47Album 13 contains copies of issues 1 to 8, and issue 10, which comprise the period from August 28, 1915, to August 24, 1916.

48A Opinião, A Reforma, A Tribuna, Ação Social, Gaumont, Jornal do Povo, Minas Jornal, O Dia, O Florete, O Reporter, O Zuavo.

49The archive has two handwritten copies of different versions of the operetta A mulher soldado. The manuscript used in this research is found in a paperback, hardcover, navy blue notebook, in A4 format. The cover brings the information that it composed ‘Antônio Guerra’s Theatrical Repertoire’, and the title of the two handwritten plays: n. 15 and 16. A mulher soldado - Arnaldo e a vida de um jornalista [A mulher soldado - Arnaldo and the Life of a Journalist].

52To come to this statement, we compared the two operettas most staged by the amateur club and most celebrated by the local press, namely: A mulher soldado and O Periquito [The Parakeet]. For more information on O Periquito, see Sá (2015).

54This is Sarcey’s evaluation of the drama Le maître de foges by Georges Ohnet (1883), which met the criteria of what he called a ‘well-made play’.

56Typewritten version of the play Santo Antônio nas Águas by Severiano de Resende, found in the GPAC archive. Written by an author from São João del-Rei to be staged by a group of amateurs from São João del-Rei too in 1911, we took this vaudeville as a source to understand the sensibilities, if not of the people of that city, at least of those who watched and/or produced theater shows in that place and period.

57Reference to the novel Gulliver’s Travels, by the English writer Jonathan Swift (1667-1745). “Lacking in greatness, petty, mediocre” (Houaiss & Villas, 2009, p. 463).

58The vaudeville Santo Antônio nas Águas exposes precisely this issue: the Commander, a successful widower, expressed interest in marrying the daughter of his friend Helena, little Geni. Helena hesitates, as she realizes that her daughter and Thomazinho were in love. At various moments during the play, the characters discuss the matter, always arguing that the boy and the girl should be together because they loved each other. The story is resolved with the intervention of Saint Anthony, who weds the young couple, and the commander with his friend Helena, who was also a widow.

60According to Maria Ligia Prado and Stella Scatena Franco, in the second half of the 19th century, biographical dictionaries were published, which were compendiums with the life stories of ‘notorious’ and ‘illustrious’ women. “Josefina Álvares de Azevedo, who edited, in 1897, Illustrious Gallery [Galeria ilustre], about old foreign heroines, and Inês Sabino, whose book Illustrious Women of Brazil [Mulheres ilustres do Brasil] was published in 1899. Other major references are the books by Joaquim Norberto de Sousa e Silva, Famous Brazilian Women [Brasileiras célebres] (published in 1862), and by Joaquim Manuel de Macedo, Notorious Women [Mulheres célebres] (published in 1878), about foreign female figures ‘of all times’. Macedo also produced a yearbook of Brazilian biographies (1876) that reports on the journey of several women. The magazine of the Brazilian Historical and Geographic Institute [Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro], in its turn, had (between 1839 and 1889) a column, published in almost all editions, called ‘Biography of Distinguished Brazilians as to Letters, Weapons and Virtues’ [Biografia de Brasileiros Distintos por Letras, Armas e virtues], which features the biographies of four women who lived in the colonial period” (Prado & Franco, 2013, p. 195).

61According to Prado & Franco (2013), Maria Quitéria was born in 1792, in Bahia and was an only child raised in the hinterland. She could ride horses, hunt and handle firearms. She could not read or write. Wolff (2013), on the other hand, states that Maria Quitéria lost her mother at the age of nine, and, while still young, “[...] took charge of the house and her younger siblings until her father remarried, and her new stepmother disapproved of her ‘independent manners’ and her habits of riding a horse and hunting like a man” (Wolff, 2013, p. 425).

62According to Prado & Franco (2013), Jovita Feitosa was born in Ceará, in 1848, lost her mother still as a child and was raised by her father. As a young lady, she went to live with her uncle in Piauí. Jovita could read, write, shoot and was a seamstress. She presented herself to fight in the Paraguayan war, following in her brother’s footsteps, in July 1865. According to Wolff (2013), some biographers claim that she had disagreements with her uncle, so she ran away from the farm where she lived.

63For more information on this war and criticisms by reformist officials who wrote for the magazine A Defesa Nacional, towards the campaign and the army, see Frank d. McCann (2009).

64Typewritten version of the play Santo Antônio nas Águas, by Severiano de Resende, found in the GPAC archive.

65Typewritten version of the play Santo Antônio nas Águas, by Severiano de Resende, found in the GPAC archive.

68The 1916 Civil Code creates the ‘divorce action’, and adultery was one of the reasons that justified it. However, Article 319 set some precedents for adulterers to be forgiven, rendering the divorce action illegitimate. “Art. 319. Adultery will no longer be a reason for divorce: I. If the plaintiff has contributed to the defendant committing it. II. If the innocent spouse has forgiven them. Single paragraph. Adultery is presumed forgiven when the innocent spouse, aware of it, cohabits with the guilty party” (Brasil, 1916).

How to cite this article: Sá, C. M., & Galvão, A. M. O. “A mulher soldado on stage” (São João Del Rei, Minas Gerais, 1916):an operet in scene educating sensibilities. (2021). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e144

Received: April 01, 2020; Accepted: November 03, 2020; Published: December 02, 2020

texto en

texto en