Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.21 Maringá 2021 Epub 23-Dez-2020

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e155

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

‘Men who taught America to read’: adult education in Brazil and Mexico(1947-1956)

1Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho, Marília, SP, Brasil.

2Universidade Tiradentes, Aracaju, SE, Brasil.

This text aims to analyze the relationship established between Jaime Torres Bodet and Manuel Bergström Lourenço Filho in adult literacy campaigns that took place in Mexico and Brazil, which culminated with the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education being held in Brazil, in 1949. It is, therefore, an investigation about the circulation of ideas that guided adult education in Brazil and Mexico, at a time when Mexico was standing as a successful reference for all of Latin America, above all, due to the experiences carried out by UNESCO, the OAS and the Crefal. Regarding theoretical and methodological options, this is a work based on Connected History and took newspapers, magazines and photographs as sources. Finally, it can be concluded that the relationship between those men was constituted in the campaign movement to eradicate adult illiteracy, carried out in their respective countries by UNESCO, which resulted in congresses being held and, consequently, in a vast intellectual and didactic production on the topic.

Keywords: adult education; Jaime Torres and Lourenço Filho; adult literacy campaigns; Unesco; Crefal

Este texto tem por objetivo analisar a relação estabelecida entre Jaime Torres Bodet e Manuel Bergström Lourenço Filho, nas campanhas de alfabetização de adultos no México e Brasil, que culminaram com a realização do VI Seminário Interamericano de Alfabetização e Educação de Adultos, no Brasil em 1949. Trata-se, portanto, de uma investigação acerca da circulação de ideias que nortearam a educação de adultos no Brasil e México, em tempos em que o México se colocava como referência exitosa para toda a América Latina, sobretudo, pelas experiências levadas a cabo pela Unesco, OEA e Crefal. Em relação às opções teórico-metodológicas, trata-se de um trabalho embasado na História Conectada, tomando como fontes: jornais, revistas e fotografias. Por fim, pode-se concluir que a relação entre esses homens se constituiu no movimento campanhista de erradicação do analfabetismo adulto, levado a cabo em seus respectivos países pela Unesco, que resultou na realização de congressos e, consequentemente, em uma vasta produção intelectual e didática sobre o tema.

Palavras-chave: educação de adultos; Jaime Torres e Lourenço Filho; campanhas de alfabetização de adultos; Unesco; Crefal

Este texto tiene como objetivo analizar la relación establecida entre Jaime Torres Bodet y Manuel Bergström Lourenço Filho, en las campañas de alfabetización de adultos en México y Brasil, que culminaron con la celebración del VI Seminário Interamericano de Alfabetização e Educação de Adultos en Brasil en 1949. Es, por lo tanto, una investigación sobre la circulación de ideas que guió la educación de adultos en Brasil y México, en un momento en que México se estaba colocando como una referencia exitosa para toda América Latina, sobre todo, debido a las experiencias llevadas a cabo por el Unesco, OEA y Crefal. En relación a las opciones teóricas y metodológicas, es un trabajo basado en la Historia Conectada, tomando como fuentes: periódicos, revistas y fotografías. Finalmente, se puede concluir que la relación entre estos hombres se constituyó en la campaña para erradicar el analfabetismo de adultos, llevada a cabo en sus respectivos países por la Unesco, que resultó en la celebración de congresos y, en consecuencia, en un vasto desarrollo intelectual y didáctica sobre el tema.

Palabras clave: educación de adultos; Jaime Torres y Lourenço Filho; campañas de alfabetización de adultos; Unesco; Crefal

Introduction

For some of the delegates present here - he said in his speech -, coming from countries where illiteracy has practically disappeared, it may seem anachronistic that there are peoples in which, alongside a university elite, and under the cultural remnants of a great lineage, millions of young and adult people do not even have the mastery of the alphabet. [...] We understand that the organization that is being structured is a first step and, for this reason, appreciate and applaud it. But we feel that this first step should be followed by a meeting that boldly addresses these three questions: What are they willing to do about the wealthiest and most technically prepared countries to help others raise the level of education of their inhabitants? How will we reconcile such an aid with the duty to respect the freedom of each nation in choosing its internal methods for organizing teaching in its territory? And how will we coordinate this freedom - which we judge inalienable - with the urgency of deciding on the general objectives of the education of man? (Bodet, 1969, p. 1, our translation).35

The speech by Mexican politician, philosopher and writer Jaime Torres Bodet, on the occasion of UNESCO’s Preparatory Conference36 held in London, in 1945, reverberated an alert to the theme of adult education, in the very first years after the foundation of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In that speech, his arguments took into account the social and economic disparities between UNESCO’s signatory countries37, as his voice in the organization echoed the educational demands of Mexico and, notably, of the other countries in Latin America, especially in the years in which he headed that institution (1948-1952).

This text is set in that historical period, advancing until 1956, the year of publication of the Cartilha do povo: para ensinar a ler rapidamente [People’s booklet: teaching how to read quickly], by Manuel Bergström Lourenço Filho, and aims to analyze the relationship established between Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho in adult literacy campaigns that took place in Mexico and Brazil, between 1947 and 1956, which culminated with the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education being held in Brazil, in 1949.

The antecedents of this story lie in Mexico’s past, a country which developed other experiences in matters of adult education, which resulted in the creation of the Secretaría de Educación Pública [Public Education Secretariat] (SEP), in 1921 (Miranda, 2014). With a social emphasis, a model of adult education was built in that country, with especially revolutionary38 characteristics, as of 1910. These historical conditions laid the foundation for the construction of rural schools, cultural missions, rural normal schools and school farms, supported by the concept of fundamental education - recently created, at the time, by UNESCO, especially with the creation, in 1951, of the first Centro Regional de Educación Fundamental para la América Latina [Regional Center for Fundamental Education in Latin America] (Crefal)39, in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, Mexico.

The idea of fundamental education, supported by UNESCO, has as cornerstone the theory of modernization and responds to the format of the international organizations of the time; based on a notion: “[...] sufficiently broad and general [...]” and on a “[...] diagnosis of the whole region, a set of intervention techniques and strategies is elaborated, which are replicated as a ‘recipe’ in different countries” (Fernández, Welti, & Guida, 2009, p. 249-250, our translation, author’s emphasis)40. This without taking into account the particularities of the different contexts; in this case, the Brazilian and Mexican experiences. However, to create a standard concept, a universal definition, a working group composed of representatives from the United Nations’ secretariats and from specialized institutions, gathered in Paris in November 1950, sanctioned:

This name, fundamental education, is given to a minimum general education that aims to help children and adults deprived of the benefits of a good school instruction understand the peculiar problems of the environment in which they live, in order to give them an exact idea of their civic and individual rights and duties, and so that they participate more effectively in the social and economic progress of the community to which they belong. This education is fundamental because it provides the minimum theoretical and technical knowledge necessary to achieve an adequate standard of living. It is an indispensable prerequisite for the activity of specialized services (hygiene, agriculture, etc.) to be fully effective. (Centro Regional de Educación Fundamental para la América Latina [Crefal], 1952, p. 14-15, our translation).41

One of UNESCO’s tasks was to foster fundamental education as the minimum education that the adult population needed. Based on this concept, the Campanha de Educação de Adolescentes e Adultos [Campaign for the Education of Adolescents and Adults] (CEAA) was developed in Brazil, and the Campaña Nacional pro alfabetización [National Campaign for Literacy] was developed in Mexico, between 1947 and 1963. The principles of fundamental education became known, especially, with the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education, held at Hotel Quitandinha, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, from July 27th to September 2nd, 1949. On that occasion, several intellectual references on adult education were present.

Regarding theoretical and methodological options, this text is based on the assumptions of connected history. This historiographical reference consists of a theory/method that establishes connections by promoting dialogue. In this sense, we take on the task of a historian in charge of “[...] exhuming historical links or, to be more precise, of exploring connected histories” (Gruzinski, 2003, p. 19). To this end, we had to become some: “[...] kind of electrician in charge of reestablishing international and intercontinental connections” (Gruzinski, 2003, p. 19). The electrician metaphor, about reestablishing international and intercontinental connections, provided by the French historian Serge Gruzinski, is used to connect a web of relations concerning adult education in the Brazil/Mexico space.

In light of the foregoing, we came to some questions: How was the relationship between Lourenço Filho and Jaime Torres Bodet established in favor of adult education in Latin America? How and why did Brazil appropriate Mexican initiatives for adult education? What type of material was used to teach adults to read and write in both countries? What did the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education in Brazil represent?

“Viejito... Pero aprendiendo”42: the adult education campaign in Brazil and the Mexican example

Brazil Campaign for Literacy

A campaign in Brazil aimed at teaching illiterates of all ages to read and write has resulted in the establishment, since the beginning of 1947, of nearly 14,000 schools. This was announced by the Brazilian Director-General of Education, Dr. Lourenço Filho, delegate to UNESCO’s Second General Conference, at a press conference in Mexico City on November 25, who declared that it was largely due to Mexico’s example that Brazil embarked on its campaign of Fundamental Education (Brazil campaign for literacy, 1948, p. 4, our translation).43

In the interview given by Lourenço Filho, it was evident that the Mexican example, in its set of initiatives, stood out worldwide and, consequently, aroused the interest of well-known educators. As was the case with Lourenço Filho, who traveled to Mexico twice, carrying out an institutional work plan, especially on the occasion of UNESCO’s Second General Conference (1947) and the 1 st Meeting of the Inter-American Cultural Council (1951), besides traveling around the country seeking to observe the development of adult education, mainly in rural areas. Evidence of this was the images of the Crefal’s actions found in Lourenço Filho’s collection, just as this one showing a poster that announces: “Viejito ... pero Aprendiendo” (Figure 1):

In the government of President Eurico Gaspar Dutra (1946-1951), Clemente Mariani (then Minister of Education and Health, between 1946 and 1950), established, on February 1st, 1947, the Serviço de Educação de Adultos [Adult Education Service], appointing teacher Lourenço Filho as coordinator of the Campanha de Educação de Adultos [Adult Education Campaign]. According to him, the proposals of UNESCO and of the Organization of American States (OAS) should be followed: “[...] in their capital lines” (Lourenço Filho, 1947, p. 14), because in that period, the Campanhas de Jovens e Adultos [Youth and Adult Campaigns] consolidated UNESCO’s universal assumptions and recommendations. According to Paiva (1987), with the emergence of UNESCO, Brazil began to suffer external pressure to invest in this matter. UNESCO, therefore, unveiled to the world the deep inequalities between countries and: “[...] warned about the role that education, especially adult education, should play in the development process of nations categorized as ‘backward’“ (Haddad & Di Pierro, 2000, p. 111, author’s emphasis).

Jaime Torres Bodet proposed the creation, by UNESCO, of regional adult education centers: “[...] the world population totaled 2,378 million people. Of those, 1,200 million did not know how to read and write. The urgency and need to deal with this vast number of illiterates was obvious.” (Guerra, 2002, p. 12, our translation)44. Consequently, it was considered that this network of adult education centers would allow reducing the number of illiterates worldwide.

This investment by UNESCO in campaigns to eradicate adult illiteracy included the creation of postage stamps. The article written by C. W. Hill, entitled Les timbres, alliés de l ‘A. B. C., or Stamps, allies of A. B. C., gathers information on postage stamps made with the purpose of representing the image of their respective countries, as nations committed to fighting illiteracy in the adult population. Figure 2 below shows the stamps of the literacy campaign in Brazil and Mexico.

Source: The UNESCO Courier (1958b, p. 29)

Figure 2 Stamps of the adult literacy campaign in Brazil and Mexico.

The Brazilian and Mexican stamps, respectively, read:

Carrying out large-scale campaigns for adult education is no easy task in a country like Brazil, where there are immense tracts with a population of about one per square mile. But this is what the Government has been doing since 1947 after statistics revealed that over 50 percent of the adult population was illiterate. Deciding on a mass solution, the Government initiated a plan for opening 10,000 evening schools for adult and adolescent illiterates. The stamp symbolizes the light of education (The UNESCO Courier (1958b, p. 29, our translation).

Removing the bandage of illiteracy symbolizes, on this Mexican stamp, the large-scale educational effort made by Mexico in recent years. One of the most remarkable achievements was the nation-wide campaign initiated and developed between 1943 and 1946 by Jaime Torres Bodet. Minister of Education who later (1948-53) became Director-General of UNESCO (The UNESCO Courier (1958b, p. 29, our translation).

In both cases, the author considered the role of Lourenço Filho and Jaime Torres Bodet as fundamental in the large-scale campaigns to fight adult illiteracy. In the case of the Brazilian stamp, it reads: ‘Brasil Correio ABC - Adult Education Campaign’; it depicts a man, purposely adult, reading, and, in the background, an explosion of light that alludes to the light brought by knowledge school. In the case of the Mexican stamp, it reads: ‘Quitemos la venda! Campaña Nacional pro alfabetización’; it depicts hands that remove the blindfold from an adult’s eyes, indicating the need to read the world.

Henceforth, multilateral organizations, notably UNESCO, through committees and commissions, with their recommendations, resolutions, conventions and international agreements on educational matters, sought, indispensably, to guide or even intervene in general and specific national educational policies uniformly, through the convergence of principles, theoretical precepts, teaching and learning materials, didactic, pedagogical and educational procedures, and recipients of public education policies for youths and adults. According to Araújo, Alcoforado and Ferreira (2015), in the 1940s and 1950s, Brazil made Adult Education Campaigns official, in the course of 16 years (1947-1963), which were “[...], aimed particularly at groups of youths and adults aged 14 to 35 years old who had not attended school or had left early” (Araújo, et al., 2015, p. 17).

Adult education campaigns, which took place concurrently in other countries of the world, were important because they defined the basic principles on which adult education worldwide should be founded. According to the list of projects associated with UNESCO in Latin American countries, Brazil was first place, and Mexico, fourth: “1. Brazil - Campanha de Educação de Adultos; 4. Mexico - Ensayo Piloto de Educación Fundamental de Nayarit” (The UNESCO Courier (1958b, p. 29). In the Brazilian case, the deliberations of the campaign ended up resulting in a project for the development of Cultural Missions, inspired by Mexican educational experiences targeting the rural environment.

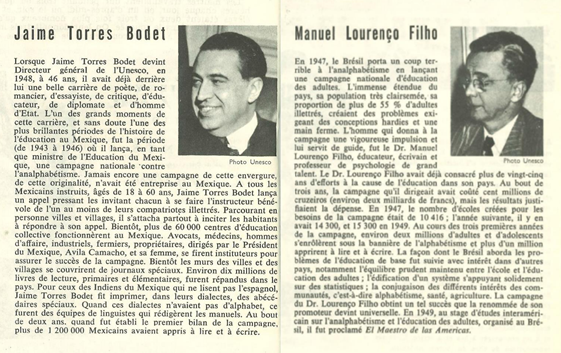

In an article published by El Correo de la UNESCO (Educación fundamental por Jonh Bowers, 1948, p. 4, our translation), Lourenço Filho states that: “The campaign will also be extended through cultural centers and missions, and the number of students is expected to exceed one million in 1948”. In another article - Fighters for literacy - Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho share the same page of the newspaper The UNESCO Courier. In it, both were highlighted for their involvement in adult education campaigns in their respective countries (Figure 3):

Source: The UNESCO Courier (1958a, p. 22-23)

Figure 3 Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho on the same page of The UNESCO Courier.

In the article, Jaime Torres Bodet is described as a great consolidator of the public policy against illiteracy, culminating with the creation of 60,000 collective education centers, in addition to printed materials of a varied nature (newspapers, books and booklets) meant for the literacy project aimed at youths and adults. The article praises the translation of the booklets into indigenous dialects, which had no written form up until that time, and, finally, informs that in only two years the result of the project was just over 1.2 million literate people, which gave Mexico international visibility.

Lourenço Filho, in his turn, was awarded with the title of ‘Maestro de las Américas’, granted to him for his knowledge of the education systems in Latin American countries, for his projection in the most diverse areas of intellectual production and in the most distinct government bodies between the 1920s and the 1960s. The article emphasized that his actions determined the tracks of adult education in Brazil in the 20th century, mainly due to his work with UNESCO, especially when he was leading the Campaign. The results considered positive of that leadership, which, in the first three years, reached about 2 million enrolled adults and adolescents, gave Brazil international recognition, resulting in the country being chosen to host the 6 th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education. Here is what both articles state, respectively:

When Jaime Torres Bodet became Director-General of UNESCO, in 1948, he had already behind him a distinguished career as poet, novelist, essayist, educationist, diplomat and international statesman. One of the high points of his career and certainly one of the most brilliant phases in the history of Mexican education was the period (from 1943 to 1946) when He served as his country’s Minister of Education and initiated and developed a nation- UNESCO’s wide campaign against illiteracy. No campaign of such scope or originality had ever before been undertaken in Mexico. Torres Bodet appealed to all educated Mexicans to become ‘emergency’ teachers for at least one of their illiterate country men and He toured towns and villages arousing and inspiring the people. Soon, over 60,000 collective teaching centers were organized and lawyers, doctors, businessmen, industrialists, farmers and landowners led by the President of Mexico, Avila Camacho, and his wife, joined in as teachers to make the campaign a success. Special wall newspapers were printed and over 10,000,000 elementary Reading books and primers began flooding the country. For those Mexico’s Indians who did not speak Spanish, Torres Bodet had special primers prepared in their languages, and where these languages had never before been written down, He called in teams of linguists to do this. When the results were tabulated after only two years of work, it was found that over 1,200,000 Mexicans had been taught to read and write. The successful campaigns encouraged other Latin American countries to adopt similar methods (1958a, p. 22-23, our translation).

Brazil began a full-scale attack on illiteracy in 1947 by launching a nationwide adult education campaign. The country’s tremendous and sparsely populated area and an adult illiteracy figure of over 55 percent created problems whose solution called for bold conceptions and methods of fundamental education and for vigorous leadership. The man who gave leadership and driving force to the campaign was Manoel Lourenço Filho. One of UNESCO leading educators in Brazil, author and professor of psychology, Lourenço Filho had already devoted his efforts for more than a quarter of a century to the cause of education in his country. The cost of the first three years of the adult education campaign, 100 million cruzeiros (55,000,000), was justified by the results. In 1947, there were 10,416 ‘Campaign’ schools in operation; in the following year, 14,300, and in 1949 the number reached 15,300. In the first three years about 2,000,000 adults and adolescents enrolled and more than 1,000,000 people were taught to read and write. Brazil’s approach to fundamental education problems was watched with interest in other countries: the careful balance maintained between school and adult education; the building on a solid basis of statistical fact and the linking together of the varied interests of communities in literacy, better health and farming. Lourenço Filho’s successful leadership of the campaign won him international recognition, and at the 1949 Inter-American Seminar on Illiteracy and Adult Education, he was hailed as El Maestro de las Americas (Teacher of the Americas) (The UNESCO Courier, 1958a, p. 22 -23, our translation).

With Jaime Torres Bodet heading UNESCO, Mexico rose as a pioneer laboratory for large-scale educational experiences, perfecting investigations that aimed to achieve the same teaching quality and levels of international education systems, with a view to a more effective margin of results regarding school-age and out-of-school literacy. Thus, Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho were individuals who worked in their respective countries by means of national and international policies to fight illiteracy and of adult education campaigns. According to UNESCO, they were men: “[...] who taught their people to read in America” (The UNESCO Courier (1958a, p. 21, our translation)45 and, for this reason, to a certain extent, were subjected to mutual influence, with the exchange of educational references. The Mexican experiences, with their methods and theories, served as a reference for other education campaigns for adolescents and adults in other countries, including Brazil.

In the 1940s and 1950s, Brazil and Mexico were the countries with the largest population in Latin America, as together they had approximately half of its inhabitants. Therefore, the absolute numbers of adult illiterates were worrisome in both countries. In the 1950s, Brazil had an illiteracy rate of 51% in the population over 15 years old, and Mexico, 43%. However, this statistical systematization must be questioned. Far from being neutral, “[...] the statistics express positions and interests well delimited by the way data are organized, within the formulated categories, as to the decision of what to include and what calculations to make” (Gil, 2007, p. 19). Regarding the educational statistics used by UNESCO, they arose growing interest in this historical moment because they synthesized two of the signs of modernity with which, back then, Brazil and Mexico sought to align themselves: scientific rationality and elementary school.

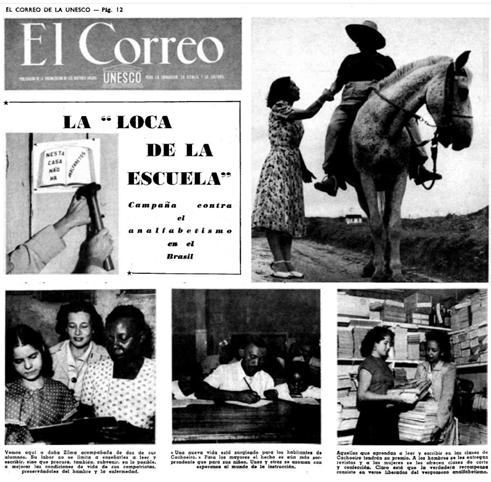

In the Brazilian case, the involvement of teacher Zilma Coelho Pinto and her pedagogical planning in favor of literacy, social assistance and professionalization, during the first CEAA, in Cachoeiro de Itapemirim, Espírito Santo, between 1947 and 1963, gained international relevance. The literacy plan proposed by teacher Zilma “[...] involved other contents, namely: values and behaviors based on concerns with hygiene, health and morality” (Costa, 2017, p. 279). Her case was featured on a page in El Correo de la UNESCO, entitled “La ‘loca de la escuela’: campaña contra el analfabetismo en el Brasil” (Figure 4). According to the publication:

The beginning was very difficult, and Dona Zilma had to show a lot of patience and energy to raise a modest sum to undertake her campaign, facing, impassively, the mockery and criticism of many. There were those who called her ‘the madwoman from Itapemirim’; some would also call her by the ridiculous name of ‘the beggar’ [...] But Dona Zilma was not discouraged by so little: now on foot, now on horseback, she organized fundraisings in all neighborhoods of the city and in the countryside nearby (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1950, p. 12, our translation, author’s emphasis).46

Source: El Correo de la UNESCO (1950, p. 12)

Figure 4 Zilma Coelho Pinto, in Cachoeiro de Itapemirim, Espírito Santo, 1947.

The active participation of teacher Zilma in the CEAA built a good relationship between her and teacher Lourenço Filho. Costa (2017) found, in the personal documents archived by her family, a letter sent and signed by Lourenço Filho, which is believed to be a preface to a book about the campaign led by her. In it, Lourenço Filho does not spare words in praising Zilma’s efforts, and such a relationship, in a way, explains the dissemination of that teacher’s actions on the pages of the newspaper El Correo de la UNESCO. Here we have to ask: How were Lourenço Filho and Jaime Torres Bodet involved in the adult literacy publishing market?

“Teaching how to read quickly”47: adult literacy booklets in Brazil and Mexico

May the People’s booklet, as its own title indicates, continue to contribute to the education of children and adults, even those who are the farthest from the big centers, teaching millions of Brazilians how to read and write, in the simplest manner. Popular education is certainly not limited to this learning. Reading and writing represent only an instrument, not bringing a purpose in themselves. Educating the people will also give them civility, production capacity, health, sound employment of leisure hours (Lourenço Filho, 1956, p. 2).

The words above were extracted from the recommendation ‘To the teachers’, which opens the People’s booklet: teaching how to read quickly, by Lourenço Filho (1956). He had a close relationship with the publishing market of that time, relationship which was translated into numerous published, prefaced or organized titles. According to Silva and Guimarães (2017), Lourenço Filho’s literacy proposal synthesized in the People’s booklet “[...] corresponded to the attempt to meet the demands for eradicating illiteracy, especially with regard to children and adults” (Silva & Guimarães, 2017, p. 4382). The author’s greatest concern was, therefore, with providing an educational tool of popular reach, corresponding to the technique of reading and writing, understood as a way of acquiring literate culture.

Upon taking on the direction of the CEAA, the intellectual carried out the actions of the pedagogical orientation sector, supervising the preparation of the material that would be distributed by the campaign. As prescribed by UNESCO in its recommendations, at least the initial material of the Campaign, intended for the first literacy cycle, indicated general concerns with the formation and adaptation of the citizen to the social environment. Then, one is given rules as to the good preservation of “[...] health, which range from care against flies, mosquitoes and lice, vectors of diseases, to the recommendation of eight hours of sleep per day for the worker’s recovery” (Azevedo, 2019, p. 93).

By fostering the process of wide distribution of the material aimed at the literacy and reading capacity of adults reached by the ongoing campaign movement, Lourenço Filho places the campaign within the charts of comparison with the other countries in Latin America. As a result, Brazilian localism tended to circulate internationally with the aim of sharing pedagogical experiences.

The Mexican experience served as a model for Brazil, including in the publishing aspect. In that period, the Ministry of Education: “[...] printed five hundred thousand ‘Reading Guides’ with the aim of serving the national adult literacy plan, [...] just as what has already been done in other countries of the world, especially Mexico” (Brazil, 1947, p. 08, author’s emphasis). From the studies by García (2014), the National Campaign against illiteracy, carried out in Mexico by Jaime Torres Bodet, has points of similarity with the Brazilian campaign, namely: fight against the common enemy of illiteracy; call for volunteering; use of specific booklets for adults, among other characteristics.

According to the report A educação rural no México [Rural education in Mexico], prepared by Lourenço Filho, the maxim ‘Knowing how to read and write’, as the minimum necessary for the individual: “[...] was not equal for all Mexicans - we judge imperative to propose the issue in national terms” (Lourenço Filho, 1952, p. 162). The matter of illiteracy in Mexico lied in social problems, such as alcoholism, crime, begging and the precarious development of agriculture and industries. In that context, the campaign against illiteracy should target, in particular, rural and indigenous populations, especially the speakers of the maya, tarasco, otomi náhuatl, náhuatl languages:

[...] the rural populations, which had, and still has, the highest rate of illiterates, and in which entire communities of the indigenous population also do not speak Spanish. So that education could reach these populations, a special institute was created, which was responsible for writing booklets in maya, tarasco, otomi náhuatl (Puebla’s variant) and náhuatl (Morelos’ variant). A group of fifty teachers, who knew these native languages, were prepared to transmit to rural teachers the most recommended teaching processes in each case (Lourenço Filho, 1952, p. 162, author’s emphasis).

At the time, part of the problem of the indigenous people was their complete lack of knowledge of the official language, Spanish, which precluded their educational and civic status. In order to try to solve this problem, suitable booklets were developed for the literacy of the indigenous population in four different languages: náhuatl/español, otomí/español, maya/español, tarasco/español.

It was in that context that UNESCO organized, together with the government of Brazil and the OAS, the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education, in 1949.

“América se alfabetizará48 - aportación quedará nuestro país”: the vi inter-american seminar on adult literacy and education

America will become literate - the contribution that our country will give

Mexico will take to the Seminar on Practical Studies on Literacy in America, which, at the initiative of UNESCO’s Secretary-General, Jaime Torres Bodet, was inaugurated today in the city of Rio de Janeiro, all of the technical collection and experiences acquired in our country and in the courses of the work of the National Campaign against illiteracy. Our teaching authorities have the purpose of providing the sister nations of the Continent, which were deeply interested in the educational work that is being developed in the country, with detailed information about the achievements in our land, with regard to the cultural incorporation of illiterates. [...] Teacher Bonilla will take with him an extensive documentation about how the tremendous problem of illiterates in our country is being tackled, including illustrative films, charts and various illustrative elements (News, 1949, p. 1, our translation).49

The article written in the Mexican newspaper Novidades explains Jaime Torres Bodet’s intention to take to the 6 th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education50, held at Hotel Quitandinha, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro, from July 27th to September 2nd, 1949, Mexico’s social and technical experiences, which included illustrative films and charts used in the Campaña Nacional pro Alfabetización underway in the country. Mexico’s then Secretary of Public Education, Manuel Gual Vidal, sent a delegation to the Literacy Seminar, led by teacher Guillermo Bonilla, known as El Maestro, who organized the famous Cultural Missions for literacy in Mexico, and then director of extracurricular education.

The year 1949 was remarkably singular for adult education globally. UNESCO’s out-of-school education sector listed two important events that addressed the theme, with the first being the Conference held in Elsinore51, and the second, the 6 th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education. In this sense, the recommendations and agreements that were deliberated from these meetings: “[...] represent a desire for change on the part of the nations and of the body of summoned experts, but also a clash for disputes over the visibility of the political and pedagogical projects being debated” (Azevedo, 2019, p. 111). These spaces legitimized by UNESCO served to discuss the fate of adult education worldwide, in addition to being a place for the circulation of references rendered legitimate for the matter to be approached.

The 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education took place in collaboration with UNESCO, the OAS, the International Labor Organization [ILO], the World Health Organization [WHO], Geneva’s International Bureau of Education52 (headed by Jean Piaget at that time) and, in the Brazilian case, the Brazilian Institute of Education, Science and Culture (Instituto Brasileiro de Educação Ciência e Cultura) [IBECC]. These international organizations fostered a unique agenda in adult literacy and education on the American continent, reinforcing the collective transnational project for attention to the high levels of illiteracy statistically identified, which leave the shadows of nationally located problems to join the global outcry addressed by Torres Bodet at the opening meeting of the Seminar held in Brazil. The event was published in The UNESCO Courier, with the following title: The Latin American struggle against illiteracy (Figure 5):

Source: The Latin American struggle against illiteracy (1949, p. 11)

Figure 5 The UNESCO Courier’s article on the Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education, Rio de Janeiro, 1949.

Considering the 1949 scope only, the space that the literacy of adults occupy on UNESCO’s institutional agenda becomes evident. Main entity guiding the means for education universalization, UNESCO was the body responsible for establishing a dialogue between parties of interest and the exchange of knowledge, in order to: “[...] guide the main objectives of the educational banner, organize seminars and conferences for the debate, and level new ideas, research and field results” (Azevedo, 2019, p. 112). UNESCO’s recommendations included the organization of international seminars on the education of adolescents and adults, as published in El Correo de la UNESCO:

In order to achieve UNESCO’s goals and put into practice the recommendations of the Conference, (the suggestion) is to create a body for cooperation between the institutions and the people who lead adult education worldwide. It is inferred that an organization of this sort must, in the current circumstances, make use of the facilities offered by UNESCO and operate through it. [...] Another important resolution, adopted by the Conference, underlines, in order to extend the adult education movement around the world, the need to organize international seminars for studying the particular problems of adult education. ‘It is a role of UNESCO, the resolution states, ‘V we earnestly recommend that UNESCO organize from now on a seminar to be held in 1950’ (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1949a, p. 8, our translation, author’s emphasis).53

On the occasion of that seminar, delegates, observers and technicians from American countries (Guatemala, Mexico, Venezuela, notably) were present, including Colombia’s Minister of National Education and member of UNESCO’s Executive Board, Guillermo Nannetti. According to the newspaper El Correo de la UNESCO, said educator was a: “[...] specialist in fundamental education and adult education. He is currently in charge of the adult education group of the Seminar to study illiteracy in America” (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1949c, p. 12, our translation)54. The photo below shows Guillermo Nannetti, Lourenço Filho and other educators at said seminar (Figure 6):

Figure 6 Francisco Jarussi, F. J. Rex, Carmela Tejada, Lourenço Filho and Guillermo Nannetti at the Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education, 1949.

Guillermo Nannetti, together with other specialists, composed, during the five weeks of the seminar, the first Manual de educación de adultos [Adult Education Guide], later published in Portuguese and Spanish. The document addressed the fundamental aspects of adult education (Tejada, 1950), namely: objectives and content; method; action of primary social groups; institutions and means; educators of adults. The names of the main guests at that seminar were disclosed in a note published on October 1, 1949, by El Correo de la UNESCO. In it, the following figures are listed:

[…] the organizer of the famous ‘Cultural Missions’ of literacy in Mexico, Teacher Guillermo Bonilla Segura, known simply throughout his country as ‘El Maestro’; the young and energetic Ismael Rodríguez Bou, pedagogical researcher from Puerto Rico; the great and sharp statistical spirit from Argentina, Ernesto Nelson; the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget; the literacy booklet specialist Aun Nolan Ciar, from the United States, and Colonel George Selwyn Simpson, with his 35 years of experience in literacy teaching in the British Army. The Government of Brazil sent its pedagogy experts to this seminar: Fernando Tude de Souza, Antonio Almeida Júnior, Mário Teixeira de Freitas and Mário Paulo de Brito. Dr. ‘Lourenço Filho’, who so successfully headed, in Brazil, the campaign against illiteracy for two and a half years, left his office, on the fourteenth floor of the ultramodern Ministry of Education and Health, to take on the direction of the international seminar (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1949b, p. 2, our translation, author’s emphasis).55

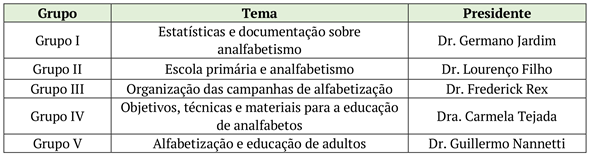

The names mentioned show the network of national and international politicians, educators and intellectuals involved in that seminar. Chart 1 shows the groups, themes and names of the presidents of the seminar (Chart 1):

Source: The author.

Quadro 1 Groups, themes and names of the presidents of the Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education, 1949

Here it is also necessary to mention that the Swiss teacher Jean Piaget56 participated in the seminar as a representative appointed by Jaime Torres Bodet, because, as noted above, he held the highest position at UN’s International Education Bureau. According to Lourenço Filho’s speech, on the occasion of the opening of the event: “Here we feel supported by the United Nations, whose Secretary-General was kind enough to send his worthy representative.” (Lourenço Filho, 1950, p. 19, our translation)57. And he continued saying that the “[...] the eminent Director of UNESCO, Dr. Jaime Torres Bodet, sent us such an expressive message and presented such a great figure, Teacher Jean Piaget” (Lourenço Filho, 1950, p. 19, our translation) 58. Figure 7 shows the Swiss teacher at said event:

Source: Tejada (1950, p. 9).

Figure 7 From left to right: Jean Piaget, Lourenço Filho; Ernesto Nelson and Teixeira de Freitas standing up while talking about statistics in Brazil.

Jean Piaget’s participation in that seminar, given his intellectual importance, gave the event greater theoretical robustness. However, here we ask ourselves: Did this intellectual have any pedagogical reflection on adult education? Did his studies on genetic epistemology and child phases apply - in the same way - to illiterate adults? Part of the answer to these questions is in the reflections of Di Pierro, Joia & Ribeiro (2001). According to these authors, the 1947 Campaign

[...] also allowed the establishment, in Brazil, of a field of pedagogical reflection around illiteracy and its psychosocial consequences; however, it did not produce any specific methodological proposal for adult literacy, or a specific pedagogical paradigm for this type of teaching. This would only occur in the early 1960s, when Paulo Freire’s work began to channel several experiences of adult education organized by different actors, with varying degrees of connection with the government apparatus (Di Pierro, Joia & Ribeiro , 2001, p. 61).

Another hypothesis to answer these questions lies in the mistake of considering that the literacy process would be the same at any age, that is, with the use of methods and theories that were identical to those used with children in primary education for adult education. Only then, starting with Paulo Freire and the set of experiences provided by the programs of the Movimento de Cultura Popular do Recife [Recife’s Popular-Culture Movement], of the Movimento de Educação de Base [Basic Education Movement] (MEB), both started in 1961, of the Centros Populares de Cultura da União Nacional dos Estudantes [Popular Cultural Centers of the National Student Union], it was possible to build a theoretical and, above all, methodological framework in terms of adult education.

Certainly, that event denoted the close relationship that was established between Lourenço Filho and Jaime Torres Bodet, through that seminar. Such closeness was also shown in an article published in El Correo de la UNESCO, entitled ‘Un problema mundial’:

It is to be expected that the quality of the participants and the good organization of the Seminar entrusted to the Brazilian teacher ‘Lourenço Filho’ would contribute, at a high level, to the success of this company.

For its part, UNESCO has insisted, with special emphasis, on the global character that the Seminar should have. Dr. ‘Jaime Torres Bodet’, on behalf of the Institution, invited all countries to send their representatives (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1949c, p. 1, our translation, author’s emphasis).59

According to Lourenço Filho’s statement on the occasion of that seminar, adult education, especially in Latin American countries, was insufficient, as it was unable to contribute to raising the standard of living. “[...] this even explains the indifference of people towards it, the low school attendance and the lack of social prestige of the teacher, as well as the latter’s insufficient remuneration” (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1950, p. 2, our translation)60. The inaugural message of Jaime Torres Bodet converged with the speech of Lourenço Filho, when he emphasized, in the form of questions, the role of adult education in Latin American countries.

How can one intensify literacy campaigns without neglecting the adequate reform of primary-school programs? How can one give study plans greater credibility, in accordance with the diversity of regions, and how can they be more rationally adapted to the needs of rural communities? And, finally, how to make the principle of compulsory education a reality? In short, it is a matter of progressively eliminating illiteracy and raising, step by step, the standard of living by means of an education system that embraces all, and with simultaneous effectiveness, i.e., primary education (El Correo de la UNESCO, 1950, p. 2, our translation).61

Jaime Torres Bodet’s questions seemed to reflect the longings of the international organization he led, namely: balanced relationship between adult literacy campaigns and the reform of primary-school programs; the meaning of curricula, in accordance with the diversity of the regions, especially in relation to the needs of rural communities, and, finally, the achievement of the full reach of compulsory education. In short, his speech was founded on UNESCO’s principles of fundamental education, inasmuch as he intended to progressively eliminate illiteracy and raise the standard of living of the adult population, especially in rural areas.

Finally, we can consider that, after five weeks of studies, debates and research, the seminar deliberated on a series of recommendations for UNESCO and the OAS, among which we can mention: improve statistical data on adult education; develop a strategy for joint action in the Americas concerning education, science and culture; offer signatory countries the necessary means for them to develop investigations on the theme; structure an inter-American center for the preparation of training materials for teachers of adults; foster research, in universities, with respect to the local community; conduct research on current methods being used in American countries to make adult education part of the education system and allow adults to obtain certificates or diplomas; prepare an activity plan to be submitted to the next Inter-American Congress.

Further considerations

To make connected history, it was necessary to take up the job of an electrician in charge of installing proper wires to establish the complex relationships between Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho. This text had as starting point some questions about adult education in Brazil and Mexico, which, despite the limits, were answered throughout this narrative.

In summary, the relationship between these men was constituted in the campaign movement to eradicate adult illiteracy, underway in their countries, which resulted in the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education Seminar being held and, consequently, in a vast intellectual and didactic production on the theme.

This seminar shaped a space for public debate on the topic, as the meetings, working groups, dinners and gatherings involving these public agents (consul, delegates, technicians, ambassadors and diplomats) helped establish a network of relationships. The activity of these individuals was decisive in the constitution of their groups and spaces of action, in the organizational networks, around UNESCO, where they moved and acted and, finally, in the constitution of political projects for adult education.

The close relationship between UNESCO and the Crefal, especially due to the role played by Jaime Torres Bodet, indicates one of the reasons why Brazil appropriated the Mexican initiatives for adult education. Thus, Jaime Torres Bodet and Lourenço Filho, given the differences of each one, were intellectuals who influenced each other and stood out in their respective countries in the fight against illiteracy in the adult population. The maxim ‘fight against illiteracy’ is the greatest point of similarity that united both with the educational and pedagogical fields. To this end, UNESCO, the OAS and the Crefal have constituted themselves as the place where their intellectual production gains the seal of legitimacy, and, consequently, through the publications that originated from seminars.

Finally, these figures became references on the theme, that is, were authorized interpreters of Latin American adult literacy policies in their respective countries, especially for the production of the didactic material used in both campaigns. From this perspective, they are given, in the activities of UNESCO, the OAS and the Crefal, the notoriety legitimized by their local actions; moreover, in the educational fields of their countries, such intellectuals developed their crafts with a view to the political actions for instituting campaigns and preparing printed materials on adult Education.

REFERENCES

Araújo, M. M., Alcoforado, J. L. M., & Ferreira, A. G. (2015). A educação supletiva nas Campanhas de Jovens e Adultos no Brasil e em Portugal (Século XX). Revista Educação em Questão, 53(39), 12-44. [ Links ]

Azevedo, F. V. (2019). A educação de adultos no itinerário intelectual de Jaime Torres Bodet e Lourenço Filho: mediações entre campanhas locais e o debate transnacional (1944-1949) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Estadual de Santa Catarina (UDESC), Florianópolis. [ Links ]

Bodet, J. T. (1969). Años contra eltiempo. México, MX: Porrúa. [ Links ]

Brazil Campaign for Literacy. (1948). The Unesco Courier, I(1), 4. [ Links ]

Brasil. Ministério da Educação e Saúde. Departamento Nacional de Educação. Campanha de Educação de Adultos. (1947). Documentos iniciais da Campanha (Publicação nº 04, jan. 1947, LF, 40f). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Arquivo Lourenço Filho. CPDOC. [ Links ]

Costa, D. M. V. (2017). Civilizar o campo: educação, saúde e iniciação profissional nos cursos de alfabetização da professora Zilma Coelho Pinto, no estado do Espírito Santo (1947-1963). Comunicações, 24(3), 279-305. [ Links ]

Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação de História Contemporânea do Brasil [CPDOC]. (2020). Recuperado de: https://cpdoc.fgv.br/ [ Links ]

Centro Regional de Educación Fundamental para la América Latina [Crefal]. (1952). Educación fundamental: ideario, principios, orientaciones metodológicas. Pátzcuaro, MX. [ Links ]

Di Pierro, M. C., Joia, O., & Ribeiro, V. M. (2001). Visões da educação de jovens e adultos no Brasil. Cadernos CEDES, 21(55), 58-77. [ Links ]

Educación de adultos. (1949a). El Correo de la Unesco, II(6), 8. [ Links ]

Educación fundamental por Jonh Bowers. (1948). El Correo de la Unesco , I(1), 4. [ Links ]

En Quitandinha los educadores fijan sus planes para la campaña latinoa mericana de “alfabetización”. (1949b). El Correo de la Unesco , II(9), 2. [ Links ]

Fernández, M. del C., Welti, M. E., & Guida, M. E. (2009). La educación rural en la Argentina: propuesta de capacitación de maestros rurales (1958-1972). In T.G. Peres & O. L. Pèrez (Org.), Educación rural en Iberoamérica: experiencia histórica y construcción de sentido (p. 242-264). Madrid, ES: Anroart. [ Links ]

Fighters for literacy. (1958a). The Unesco Courier , 22-23. [ Links ]

García, A. A. L. (2014). La alfabetización en México: campañas y cartillas, 1921-1944. Traslaciones. Revista Latinoamericana De Lectura Y Escritura, 1(2), 126‐149. [ Links ]

Gil, N. L. (2007). A dimensão da educação nacional: um estudo sócio- istórico das estatísticas oficiais da escola brasileira (Tese de Doutorado). Faculdade de Educação. Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Gruzinski, S. (2003). O historiador, o macaco e a centaura: a “história cultural” no novo milênio. Estudos Avançados, 17(49), 321. [ Links ]

Guerra, R. A. (2002). El pensamiento de Jaime Torres Bodet: una visión humanista de la educación de adultos (1ª ed.). Michoacán, MX: Crefal. [ Links ]

Haddad. S., & Di Pierro.M. C. (2000). Escolarização de jovens e adultos. Revista Brasileira de Educação, (14), 108-194. [ Links ]

The Latin American struggle against illireracy. (1949). The Unesco Courier , I(1), 11. [ Links ]

Lourenço Filho, M. B. (1947). A campanha de educação de adultos. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 11(29), 5-14. [ Links ]

Lourenço Filho, M. B. (1952). A educação rural no México. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos , 17(45), 108-198. [ Links ]

Lourenço Filho, M. B. (1950). Eco del Seminario del Río. Educación Fundamental, 2 (1). [ Links ]

Lourenço Filho, M. B. (1956). Cartilha do povo: para ensinar a ler rapidamente. São Paulo, SP: Melhoramentos. [ Links ]

Miranda, F. L. (2014). México, la UNESCO y el Proyecto de Educación Fundamental para América Latina, 1945-1951. Signos Históricos, (31), 88-115. [ Links ]

Novidades. (1949). América se alfabetizará - aportación quedará nuestro país. Novidades, 1. [ Links ]

Paiva, V. P. (1987). Educação popular e educação de adultos. São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Peres, T. G., & Pérez, O. L. (2009). Educación rural en iberoamérica: experiência histórica y construcción de sentido. Madrid, ES: Anroart . [ Links ]

Postage stamps help to fight illiteracy. (1958b). The Unesco Courier , 29. [ Links ]

Un problema mundial. (1949c). El Correo de la Unesco , II (6), 1. [ Links ]

Seminario de enseñanza primaria en Montevideo. (1950). El Correo de la Unesco , 3(10), 2. [ Links ]

Silva, R. R. N., & Guimarães, J. F. S. (2017). “Para ensinar a ler rapidamente”: a Cartilha do povo e os seus leitores no meio rural sergipano (1940-1950). In Anais do Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação (p. 4380-4393). João Pessoa, PB. Recuperado de: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1vVImmMHMKniTKJWj36SyEONLM5MAdJv0 [ Links ]

Tejada, C. (1950). The Interamerican Seminar on Literacy and Adult Education - Rio de Janeiro. Washington, DC: Pan American Union (Division of Educacion - Department of Culturals Affairs). [ Links ]

UNESCO Digital Library. (2020). Recuperado de: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ [ Links ]

Vasconcelos, M. S. (1996). A difusão das idéias de Piaget no Brasil. São Paulo, SP: Casa do Psicólogo. [ Links ]

35“Para algunos de los delegados aquí presentes - dijo en su discurso -, venidos de países en que el analfabetismo prácticamente ha desaparecido, podrá parecer ana crónico que haya pueblos en los que, al lado de una élite universitaria, y sobre los restos de culturas de gran linaje, millones de jóvenes y adultos no posean siquiera el dominio del alfabeto.[…] Entendemos que la organización que se proyecta es un primer paso y, como tal, lo apreciamos y lo aplaudimos. Pero sentimos que deberá seguir a ese primer paso una reunión que afronte valientemente estas tres cuestiones: ¿Qué están dispuestos a hacer los países más ricos y técnicamente más preparados para ayudar a que eleven los otros el nivel de instrucción de sus habitantes? ¿Cómo conciliaremos tal ayuda con el deber de respetar la libertad de cada nación en la elección de sus métodos internos para organizar la enseñanza en su territorio? ¿Y de qué modo coordinaremos esa libertad -que juzgamos inalie nable- con la urgencia de decidir acerca de los fines generales de la educación del hombre?”.

36UNESCO was created at the end of the historically known Preparatory Conference, held from 1st to 16th November 1945, at London’s Institution of Civil Engineers, as a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN). The 37 member countries included Brazil and Mexico, respectively represented by José Joaquim de Lima and Silva Muniz de Aragão, Paulo Estevão de Berrêdo Carneiro, Antônio Arruda Carneiro Leão and Jaime Torres Bodet. At the end of the conference, representatives from 37 nations signed the Constitution that gave birth to UNESCO.

37In that period, there were a total of 20 Member States: Saudi Arabia, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Czechoslovakia, China, Denmark, Egypt, United States, France, Greece, India, Lebanon, Mexico, Norway, New Zealand, Dominican Republic, United Kingdom, South Africa and Turkey.

38In this regard, see Peres & Pérez (2009).

39This center underwent several paradigm and nomenclature changes; from Centro Regional de Educación Fundamental para la América Latina [Regional Center for Fundamental Education in Latin America] (Crefal), it came to be called Centro de Cooperación Regional para la Educación de Adultos en América Latina y el Caribe [Regional Cooperation Center for Adult Education in Latin American and in the Caribbean] (Crefal), from October 1990 to the present day.

40“[...] suficientemente amplia y general y de un diagnóstico de toda la región, se elaboran un conjunto de técnicas y estrategias de intervención que luego se replican a modo de ‘receta’ en los distintos países”.

41“Se da el nombre de educación fundamental al mínimo de educación general que tiene por objeto ayudar a los niños y a los adultos, que no disfrutan de las ventajas de una buena instrucción escolar, a comprender los problemas peculiares del medio en que viven, a formarse una idea exacta de sus derechos y deberes cívicos e individuales y a participar más eficazmente en el progreso social y económico de la comunidad a que pertenecen. Esa educación es fundamental porque proporciona el mínimo de conocimientos teóricos y técnicos indispensables para alcanzar un nivel de vida adecuado. Es un requisito previo indispensable que para la actividad de los servicios especializados (higiene, agricultura, etc.) pueda ser plenamente eficaz”.

42This excerpt was taken from a photograph, which shows an educational poster by the Crefal. It means that it is never too late to become an adult.

43“Brazil Campaign for Literacy - A campaign in Brazil aimed at teaching illiterates of all ages to read and write has resulted in the establishment since the beginning of 1947 of nearly 14, 000 schools. This was announced by the Brazilian Director-General of Education, Dr. Lourenço Filho, delegate to UNESCO’s Second General Conference, at a press conference in Mexico City on November 25, who declared that it was largely due to Mexico’s example that Brazil embarked on its campaign of Fundamental Education”.

44“[...] la población mundial sumaba 2,378 millones de personas. De éstas, 1,200 millones no sabían leer y escribir. La urgencia y la necesidad de atender a este inmenso número de analfabetos eran obvias”

46“El comienzo fue harto difícil y doña Zilma debió dar prueba de gran paciencia y energía para reunir la modesta suma con que emprender su campaña, afrontando impasible las burlas y las críticas de muchos. Hubo quien la llamaba ‘la loca de Itapemirim’; también quien la bautizó con el nombre irrisorio de ‘la mendiga’ […] Pero doña Zilma no se desanimaba por tan poca cosa: a pie unas veces, otras a caballo, fue organizando colectas en todos los barrios de la ciudad y en los campos vecinos”.

47Motto/expression taken from the People’s booklet: teaching how to read quickly, by Lourenço Filho (1956).

48This expression was taken from the Mexican newspaper Novidades (1949), as a bet on literacy campaigns.

49“América se alfabetizará - aportación quedará nuestro país México llevará al Seminario de Estudios Prácticos sobre alfabetización en América, que a iniciativa del secretario general de la UNESCO, Jaime Torres Bodet, se inauguró hoy en la ciudad de Rio Janeiro, todo el acervo técnico y las experiencias recogidas en nuestro país y en el curso de los trabajos de la Campaña Nacional contra el analfabetismo. Nuestras autoridades docentes tienen el propósito de poner a disposición de las naciones hermanas del Continente que se han interesado vivamente por la obra educacional que se desenvuelve en el país, minuciosa información acerca de las realizaciones alcanzadas en nuestro medio en lo que toca a la incorporación cultural de los iletrados. [...] El profesor Bonilla lleva consigo amplia documentación acerca de la forma en que ha atacado en nuestro país el tremendo problema de los analfabetos, incluyendo películas ilustrativas, gráficas y diversos elementos ilustrativos”.

51Held in July 1949, the Elsinore Conference in Denmark was one of the first initiatives that put adult education on the international agenda. At the time, more than 150 educators were present; the event was the starting point for the international rise of Jaime Torres Bodet, then president of the conference and director-general of UNESCO, against adult illiteracy.

53“Con el fin de realizar los objetivos de la UNESCO y llevar a la práctica las recomendaciones de la Conferencia (se sugiere) la creación de un organismo de cooperación entre las instituciones y las personas que dirigen la educación de adultos en el mundo entero. Se sobreentiende que una organización de este género debe, en las presentes circunstancias, servirse de las facilidades que le ofrece la UNESCO y funcionar a través de ésta. [...] Otra resolución importante, adoptada por la Conferencia, subraya, con el fin de extender el movimiento de educación de adultos al mundo entero, la necesidad de organizar seminarios internacionales para el estudio de los problemas particulares de la educación de adultos. ‘Se trata de una función de la UNESCO’, declara la resolución, ‘V recomendamos encarecidamente a la UNESCO que organice desde ahora un seminario que se celebrará en 1950”.

54“[...] un experto en educación fundamental y educación de adultos. Actualmente está encargado de dirigir el grupo sobre educación de adultos del Seminario, para el estudio del analfabetismo en América”.

55“[...] el organizador de las célebres ‘Misiones Culturales’ de alfabetización en México, Profesor Guillermo Bonilla Segura, conocido sencillamente en todo su país como ‘El Maestro’; el joven y enérgico Ismael Rodríguez Bou, investigador pedagógico de Puerto Rico; el agudo y gran espíritu estadístico de la Argentina, Ernesto Nelson; el psicólogo suizo Jean Piaget; la especialista en cartillas de alfabetización, Aun Nolan Ciar, de los Estados Unidos, y el Coronel George Selwyn Simpson, con sus 35 años de experiencia en la enseñanza de la alfabetización en el Ejército británico. El Gobierno del Brasil envió a este seminario a sus expertos en pedagogía: Fernando Tude de Souza, Antonio Almeida Júnior, Mário Teixeira de Freitas, y Mario Paulo de Brito. Dr. ‘Lourenço Filho’, que con tanto éxito dirigió en el Brasil, por espacio de dos años y medio, la campaña contra el analfabetismo, dejó su despacho, en el decimocuarto piso del ultramoderno Ministerio de Educação e Saude, para encargarse de la dirección del seminario internacional”.

56There are other versions for the reasons why Jean Piaget came to Brazil and for his participation in the 6th Inter-American Seminar on Adult Literacy and Education in Rio de Janeiro, in 1949. According to Vasconcelos (1996), Nilton Campos (Psychology chair at the National Faculty of Philosophy) and Lourenço Filho invited him to participate in that seminar. However, it is certain that Jean Piaget represented UNESCO and, at the request of Nilton Campos, Maurício de Medeiros, Peregrino Jor and Farias Goes Sobrinho, the University Council of the University of Brazil granted him the title of doctor honoris causa. On that occasion, he gave a lecture on genetic epistemology at the premises of the National Faculty of Philosophy. In this regard, see Vasconcelos (1996).

57“Aquí nos sentimos amparados por la Organización de las Naciones Unidas, cuyo Secretario General tuvo la amabilidad de enviar a su digno representante”

58“[...] cuyo eminente Director de la UNESCO el Dr Jaime Torres Bodet, nos envió tan expresivo mensaje y mandó para presentarle una gran figura, el Profesor Jean Piaget”.

59“Es de esperar que la calidad de los participantes y la buena organización del Seminario encomendada al profesor brasileño ‘Lourenço Filho’, contribuirán en alto grado al éxito de esta empresa. Por su parte, la UNESCO ha insistido con especial acento en el carácter mundial que ha de tener el Seminario. El Dr ‘Jaime Torres Bodet’, en nombre de la Institución, ha invitado a todos los países a que envien sus representantes”.

60“[…] ello hasta a explicar la indiferencia del pueblo hacia la misma, la escasa frecuentación escolar y la falta de prestigio social del maestro, así como la insuficiente remuneración de éstos”.

61“¿Cómo intensificar las campañas de alfabetización sin descuidar la reforma adecuada de los programas de las escuelas primarias? ¿Cómo otorgar mayor credibilidad a los planes de estudio, según la diversidad de las regiones, y cómo adaptarlos de manera más racional a las necesidades de las colectividades rurales? Y, por último ¿Cómo dar realidad al principio de la escolaridad obligatoria? Se trata, en suma, de eliminar progresivamente el analfabetismo y de elevar, paso a paso, el nivel de vida gracias a un sistema de educación que abarque todo -y con simultánea eficacia-, la enseñanza primaria”.

67Received: 05.27.2020 Approved: 06.25.2020 Published: 12.23.2020 (Portuguese version) Published: 01.29.2021 (English version)

How to cite this article: Silva, R. R. N., Mesquita, I. M., & Nery, A. C. B. ‘Homens que ensinaram a América ler’: a educação de adultos no Brasil e México (1947-1956). (2021). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e155 This article is published under the Creative Commons Atribuição 4.0 (CC-BY 4) License.

Received: May 27, 2020; Accepted: June 25, 2020; Published: December 23, 2020

texto em

texto em