Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1519-5902versão On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.21 Maringá 2021 Epub 25-Jun-2021

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e186

Original Article

Institutionalization and disciplination of indigenous children in the salesian missions of Amazonas/Brazil (1923-1965)

1Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Manaus, AM, Brasil.

The text deals with the Salesian boarding schools in Amazonas / Brazil (1923-1965), with the aim of analyzing the institutionalization and disciplining strategies of indigenous children. From the dialectic, the methodology is qualitative and combines literature review and primary documentary sources. The results identify the day-to-day strategies of boarding schools such as the prohibition of native languages, socio-cultural segregation and the imposition of the Portuguese language in a multilingual context. The conclusions point to the asymmetry of social relations, the Catholic hegemony in indigenous educational contexts, the tactical activism of the inmates, the conflicting views on the boarding system, which denotes that the interpretation and understanding of Salesian education are controversial.

Keywords: disciplinary regime; boarding schools; Salesian Order; school education

O texto trata dos internatos salesianos do Amazonas/Brasil (1923-1965), com o objetivo de analisar as estratégias de institucionalização e de disciplinamento de crianças indígenas. A partir da dialética e da abordagem qualitativa, a pesquisa conjuga revisão de literatura e fontes documentais primárias. Os resultados identificam as estratégias do cotidiano dos internatos como a interdição das línguas nativas, a segregação sociocultural e a imposição da língua portuguesa em contexto multilíngue. As conclusões apontam para a assimetria das relações sociais, a hegemonia católica nos contextos educacionais indígenas, o ativismo tático dos internos, as visões conflitantes sobre o regime de internato, o que denota que a interpretação e a compreensão sobre a educação salesiana são controversas.

Palavras-chave: regime disciplinar; internatos;Ordem Salesiana; educação escolar

El texto trata sobre los internados salesianos en Amazonas / Brasil (1923-1965), con el objetivo de analisar las estrategias de institucionalización y disciplina de los niños indígenas. Desde la dialéctica y el enfoque cualitativo, la investigación combina la revisión de literatura y fuentes documentales primarias. Los resultados identifican las estrategias cotidianas de los internos, como la prohibición de lenguas nativas, la segregación sociocultural y la imposición de la lengua portuguesa en un contexto multilingüe. Las conclusiones apuntan a la asimetría de las relaciones sociales, la hegemonía católica en contextos educativos indígenas, el activismo táctico de los reclusos, las opiniones contradictorias sobre el régimen de internación, lo que denota que la interpretación y la comprensión de la educación salesiana son controvertidas.

Palabras clave: régimen disciplinario; internados; Orden salesiana; educación escolar

Introduction

The conversion and civilization of the ‘Indian’ were one of the Jesuit goals since the beginning of the Brazilian colonization. One of the strategies used was the schooling of indigenous children. This prototype shaped the colonialist conception and actions for indigenous populations until the 20th century. Diving into this history goes beyond our objectives, as it would imply scrutinizing the course of the constitution and formation of Brazilian politics, since the institutionalization of children in Brazil dates back to the 16th century.

In theoretical terms, this article is a signatory to research on colonization that particularly focuses on the situation of contact between indigenous peoples and the national society. One of the facets of colonialism is that, by centering on the dominant criteria of knowledge of the modern sciences and, for this reason, not recognizing as valid other types of knowledge, it gave rise to epistemicide, that is, “[...] to the destruction of an immense variety of knowledge that prevails on the other side of the abyssal line - in colonial societies and sociabilities” (Santos, 2019, p. 27). It is from this perspective that we insert the object in the heart of an analysis that connects it with other determinants of the Negro river reality, through historical contextualization, in search of provisional understandings, as we consider that the social-human reality is intertwined with dynamisms and contradictions.

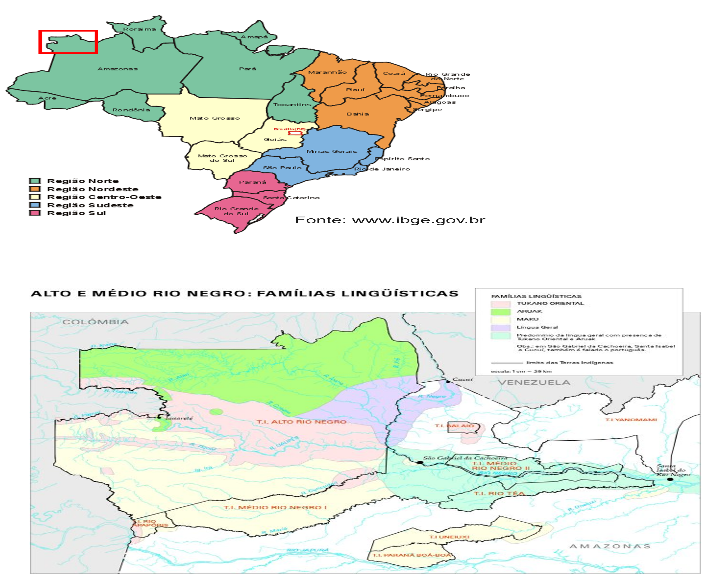

When it comes to the methodology, for delimitation purposes, the theme of this research deals with the boarding schools of the Salesian missions in Amazonas/Brazil and aims to analyze the institutionalization and disciplining strategies targeting indigenous children in said establishments. In spatial terms, the object of research is limited to the Amazonian northwest, particularly the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira (Amazonas), which borders Colombia and Venezuela, as shown in Figure 1 (next page).

Source: Cabalzar and Ricardo (2006).

Figure 1 Map of Brazil and map of Upper and Middle Negro River (Amazonas).

The Amazonian northwest is mostly made up of 23 ethnicities from the Aruak, Eastern Tukano, Maku and Yanomami linguistic groups. Due to this sociocultural and linguistic diversity, São Gabriel da Cachoeira adopted, as of 2002, the co-officialization of Nheengatu, Tukano and Baniwa (Cabalzar & Ricardo, 2006).

The explanation for choosing the 1923-1965 period is based on the understanding that it was when the work of the Salesian mission shifted away from the then village of São Gabriel da Cachoeira to spread to the strategic points of the Negro, Uaupés, Tiquié and Içana rivers, with the implantation of missionary centers where boarding schools were one of the action fronts.

What triggered the Salesian expansion process was the sending of more missionaries, by the central direction (Rome), starting in 1923, to set new foundations on the Negro river. In addition, the 1960s were marked by the official new stance of the Catholic Church, through the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), which recommended a reorientation of doctrines, structures, guidelines and undertakings in the world. The decline of the Salesian missions is associated with cuts in federal grants, with a socio-political mobilization for the formation of the indigenous movement, and with criticism against missionary activities. The Içana and Uaupés rivers were strategic for the Salesian missions because of their population density, with two language families ancestrally inhabiting them: on the Içana river, the Aruak; and on the Uaupés river, the Eastern Tukano, both families with diverse ethnic/linguistic groups.

This is a research that combines literature review and written Salesian documentary sources. In the literature review, we sought an interface with studies on the role of the Salesian Order in Amazonas (Weigel, 2000; Falcão, 2008; Silva, 2010), in Mato Grosso (Novaes, 1993; Nakata, 2008; Francisco, 2010) and in Pará (Rizzini, 2004). Besides them, we highlight the anthropological research conducted by indigenous people (Fontoura, 2006; Ferreira, 2007; Luciano, 2006; Oliveira, 2007; Rezende, 2007; Sõãliã, 2001), who are graduates of Salesian boarding schools, as the latter bring elements for the understanding of intersociety relations, from an indigenous point of view, which may eventually reveal the ‘asymmetry of perspectives’ of which Viveiros de Castro (2002) speaks, regarding the Salesians.

The sources were allocated in two missions on the Negro River and in the headquarters of the Salesian Order in the city of Manaus, so there are three institutions composing the documentary corpus of this research, namely, the missions of São Gabriel, that of São Miguel Arcanjo, and that of Nossa Senhora da Assunção. These sources, especially the chronicles, refer to the narratives that show the views and stances of European missionaries concerning people and events that took place in the day-to-day of the boarding school (chronists appointed for such a role by the mission director). Therefore, even though they cannot be taken strictly as a collectively produced and consensually assumed institutional thinking, they reveal a Eurocentric perspective on the Amerindian peoples whose base, according to Santos (2019, p. 27), is “[...] colonialism as a form of sociability based on the ethnic-cultural and even ontological inferiority of the other”.

The text begins with the introduction, in which we present a general contextualization of events that affect our object, and methodological procedures. In the second section, we highlight the disciplinary power and the institutionalization of the body in modernity. In third place come the institutionalization and disciplining strategies of boarding schools in the Salesian missions. Finally, we seek to draw conclusions from the data presented.

Starting with the contextualization, the economic situation of the arrival of the Salesians in the Amazon (1916) is marked by the rubber cycle, which eradicated the native populations from their lands, forcing them to abandon their own economic activities and compulsorily enter the extractive economy.

In geopolitical terms, the Brazil-Colombia border issues, of which the Brazilian village of Iauareté is an outpost, were on the agenda. For this reason, in the 1930s, a Mixed Commission for the demarcation of the border between Brazil and Colombia was created, whose work ended in 1937. However, this bureaucracy was, in practice, ignored, on the one hand, by the local indigenous populations, who divide the territory based on ancestral traditions, and, on the other hand, by merchants (regatões), caucheros and missionaries. These reciprocal ‘invasions’ of foreign territory led to official protests by state bodies, involving the Salesian missions even.

In political terms, the alliance of the church with the State and with local oligarchic groups, despite occasional divergences, such as the civilization of the Indian without the support of religion, defended by the Indian Protection Service [Serviço de Proteção aos Índios] (SPI), made it possible for the Salesian missions to receive subsidies from the public coffers to maintain their works (Costa, 2012).

Another scourge that plagued the indigenous populations, resulting from contact, was the ‘white people’s diseases’, which caused great mortality and, consequently, led to the indigenous depopulation in a short period of time. The Salesian missions acted on this front, opening hospitals and health units, since the general health situation had an impact on life in the boarding schools.

With regard to education and school, it can be stated that, as of the first two decades of the 20th century, pedagogical ideas were characterized by liberalism, markedly positivism and secularism, which defended the universal extension, by means of the State, of schooling as an instrument for transforming ignorant individuals into enlightened citizens. At the same time, the Catholic Church, from the 1920s, reorganized itself institutionally around the reestablishment of religious teaching and the dissemination of its pedagogical ideas. With this resumption, Catholics began to resist against the advance of new ideas, disputing with government policies and with renovators the hegemony in the educational field in Brazil, from the 1930s.

Broadly speaking, the renovators advocated for pedagogical practices based on active methods and on coexistence between the sexes, while in the sphere of public educational policies they defended the State’s monopoly in educational matters, secularism, gratuitousness, and compulsory enrollment. In their turn, Catholics fought for the primacy of the family and of the church in educational issues, separation between the sexes, compulsory religious education based on moral values, and for the family as the first party responsible for the enrollment of children, and not the State (Saviani, 2008).

As for the Union, specific school education for indigenous societies was solemnly ignored in the constitutions of 1934, 1937 and 1946, and by the National Education Guidelines and Framework Law, No. 4.024, of 1961. The action of the federal government, through the SPI, focused on opening service centers for the indigenous populations of the Negro river, but unlike what had happened in other regions of Brazil, the indigenist agency did not found schools. In their turn, at the level of the Amazonas State government, there were no public schools operating in São Gabriel da Cachoeira since the 1920s (Relatório..., 1923, 1929).

It is in this context that the Salesian missionary action, in the 20th century, proceeds under the imperative of the Jesuit perspective, along with the geopolitics of the republican State of control of lands and populations in the international border strip.

Inspired by Catholic tradition, the Salesian congregation adopted the institutionalization and disciplining of indigenous children as one of the strategies to convert and civilize adults. According to Novaes (1993, p. 168), the Salesians recognized that adults did not explicitly reject Catholic teachings, but remained stubborn in their ‘devilish and savage’ customs, a situation that led the missionaries to bet all their efforts on future generations, “[...] the true mirror of their efforts, proof not only of the feasibility, but, fundamentally, of the legitimacy of their mission [...]”, as they believed that it was desirable to forge the future on new sociocultural bases through children.

The Salesians are members of the Society of Saint Francis de Sales, founded by St. John Bosco (Don Bosco) in Italy. The Salesian work in Brazil began in 1883, in Rio de Janeiro. The Salesians settled on the Negro river, State of Amazonas, in 1916 (Costa, 2012). They opened nine missionary posts, seven of which with boarding schools for indigenous children of the Negro river: one in São Gabriel da Cachoeira (1916), one in Taracuá (1923), one in Barcelos (1926), one in Iauareté (1929), one in Pari-Cachoeira (1940), one in Santa Isabel (1947), and one in Içana (1953). The boarding schools offered teaching from first to fourth grade and received grants from the federal and state governments. The last boarding school to be closed was that of Iauareté, in 1988, with the boarding schools lasting 72 years.

We ask ourselves, therefore, what did indigenous children face in the Salesian boarding schools of Amazonas? They were confronted with the ‘different’ world of the ‘Other’. This text begins with disciplinary practices in order to identify how the universe of otherness was imposed on indigenous children.

The institutionalization and disciplining of the body in modernity

With regard to disciplinary institutionalization, Foucault (1979) identifies in the 17th and 18th centuries the invention of a new mechanism that began to coexist, converge and oppose the legal-political theory of power over land and its products. It is the mechanism of ‘disciplinary power’ over bodies and their acts, founded on discipline. However, the opposition between the legal-political (Law) and the discipline (power) realms is not absolute, as they overlap, and this overlapping helps explain the ‘society of normalization’ in which disciplinary power is composed of methods that control the operations of the body, ensuring the subjection of its forces in view of docility-utility (Foucault, 2009).

Disciplinary power over the body and its acts spread to the sphere of the education of children in the family and in the school with the purpose of disciplining the domestic and public spaces, leading the school to confine free childhood into a rigorous progressive disciplinary regime until culminating in total enclosure in boarding schools (Àries, 1981). The analysis of disciplinary power in convents, to which the Salesian boarding school is a tributary, as well as of asylums and prisons, led Goffman (2005) to classify them as ‘total institutions’, where there is a strict hierarchical division between the ‘enclosed group’ and the ‘leading group’, which guarantees social distance between them.

The enclosed group was made up of children from the Eastern Tukano, Aruak and Maku language families. The hierarchical structure of the boarding school comprised the leading group, which was composed of Salesians, mostly from the European continent, in the following positions: the principal (general responsible party), the prefect (finance), the catechist (religious education), the parish priest (to serve the people), the itinerant (visits to distant villages), the school counselor, and the assistant. The boarding school was organized by sex separation, that is, there was a boy’s boarding school (run by priests and brothers) and a girl’s boarding school (under the direction of the Salesian nuns), and the organization of time was controlled by a daily schedule for each activity, with some modifications for bank holidays and weekends.

One of the boarding school’s action fronts was formal education, the teachers of which were the Salesians themselves and the nuns. Over the years, graduates were recruited for the role of teachers.

The social relations produced in total institutions reflect the exertion of power hierarchized in capitalist societies. The organization of space, of time, surveillance, sanction, examination, and information recording will be used in our analysis, as they are, according to Foucault (2009), the materialization of the intersections between discipline and power. These devices are combined with those of a specific nature in this article, such as the interdiction of the use of indigenous languages, the imposition of the Portuguese language, and sociocultural segregation.

The control of the body and of the acts of indigenous children in the ‘civilization centers’

The analysis of boarding schools will take into account the articulation between the theme and the Amazon colonization project. For the Salesians, boarding schools were conceived as ‘centers or nuclei of civilization’, while for Weigel (2000), boarding schools are instruments for the geographical conquest of the region, and for the expansion of capitalism in the Amazon, as religious institutions, in alliance with the ruling classes, have played the role of ideological apparatus for integrationist politics, pacifying and subordinating indigenous peoples to disciplined work along the capitalist production lines.

As for their profile, indigenous children were recruited from the age of eight. The missionaries traveled to villages far from the mission headquarters (‘itinerances’), an occasion on which they defended the advantages of school education and intended to convince family members and village chiefs to send their children to the mission for them to receive school education.

What are the expectations of indigenous parents regarding the confinement of their children in the Salesian boarding schools? Although this question is difficult to answer, it is assumed that the acquisition of school knowledge was seen by parents as a way to obtain a share of the power of white people and, thus, future generations would be better prepared to establish intersociety relationships in less unequal conditions, in order to alleviate the hard suffering faced by the ancients at the hands of the whites. Therefore, several children were taken to the boarding school. Many families began to live around the mission, establishing villages, to be close to their children. This contributed to the emptying of the villages.

Indigenous children were unaware of how a boarding school operated, so at the beginning of the school year the regulations were read and explained to all boarders, but learning and the introjection of the norms and conventions required a slower process that was carried out by reiterating disciplinary rules, by demanding compliance with them, by applying punishments, and through the very coexistence with senior students in the daily routine of institutional life.

As for the selection criteria for admission to the boarding school, we assume that, in addition to those mentioned by Weigel (2000) for the Baniwa reality, namely, (1) being a child of Catholics and, (2) as to those who had a hierarchically superior status in the social traditional structure, we can add the condition of being a child of the Salesians’ representatives (teacher, catechist, captain), usually a former student. This third criterion differs from the second in that missionary interference with the sociopolitical organization of indigenous societies replaced the traditional criterion of biological seniority (the ‘big brother’) for the choice of indigenous leaders through the requirement of ideological alignment with the Salesians; thus, by ethnic standards, many captains, for instance, were ‘younger brothers’ in the social organization and, therefore, should not take the position of leaders before older brothers, which would give rise to conflict situations.

The confinement of indigenous children entailed a radical rupture in their domestic, social and cultural lives. On the one hand, this family and sociocultural segregation aimed to distance them from the influence of their groups of origin and, on the other, to inculcate new knowledge, values and customs, in order to erase thecultural traditions that formed the indigenous identity in order to transform them into Christians and civilized individuals, because, according to Sõãliã (2001, p. 15),

The adults who live today, having spent their childhood and adolescence outside their village, residing in missionary boarding schools to be educated, shaped by school education, have not had the concern to continue the cultural way of life of the Waikhana [...] Deprived of their traditional rites as to clothing, as to mythological knowledge, this is how identity and the values acquired through the ancestors is reduced. And those who are within their cultural area do not live differently from those who migrated outside their land, that is, they are just there, without traditional sacred festivals. They are interested in assimilating to the global society’s way of life.

More than the ‘lack of concern’ of the graduates in continuing cultural traditions, the ‘reduction of identity’ was the corollary of the break in the chain of transmission of knowledge from one generation to another, since, on the one hand, the transfer of knowledge from the elderly required the performance of specific rituals (initiation, for instance), which should occur in adolescence, in some cases, for exclusive recipients (such as the firstborn), but which were interrupted due to the confinement of children in boarding schools; on the other hand, the rituals were prohibited by the Salesians and, threatened by the missionaries, the elders refused to continue passing on to the new generations the traditional knowledge they carried.

Thus, generations of girls and boys were deprived of traditional knowledge, so the transmission of cultural heritage from one generation to another was interrupted, as such knowledge could only be passed on in daily life or in circumstances permeated with rituals, and by experts socially and culturally recognized for such tasks.

With segregation and confinement, the cultural-educational processes experienced up until then by indigenous children were broken. Fontoura (2006) provides parameters for the break between indigenous education and the missionary school when classifying the means for transmission of the Talyáseri’s knowledge into three categories: a) oral (narration of myths, protection and healing formulas, stories of settlements and migrations, the constellations, the seasons of the year, the hierarchy of the clans, etc.); b) oral with demonstration (material culture), and c) oral with consumption of entheogenic drink (pubertal initiation rites and shamanism). This triadic educational modality involves ritual procedures, specific times and diversified spaces, because, according to Fontoura (2006, p. 81),

In the Talyáseri culture, the maloca, the festivals and the initiation rituals (pubertal initiation to prepare the future Yawi) were the formal spaces and crucial moments for the transmission of this knowledge, including during morning baths, hunting, fishing, in the jungle, in the workplaces, almost every moment was an opportune one.

The traditional knowledge involved in indigenous educational processes concerns the totality of group life, intersociety relations, nature and the cosmos, so the construction of knowledge among the Talyáseri is constituted from the intersections between speech-listening, observation and doing. The reference to knowledge, spaces, times, transmission methodology and forms of knowledge construction involved in the educational processes of the Talyáseri allows us to identify an incompatibility between indigenous education and Salesian education, since the latter was based on confinement and on disciplining.

Rizzini (2006, p. 142-143) states that, upon entering the boarding school, the student was invested with a “[...] new identity, that of an apprentice, made uniform in their garments and treatment”. The symbols of this new condition included clothing, manual labor instruments, school supplies, among others, of which they should take care as being their own. This individualism was contrary to the indigenous ways of life, as, according to Luciano (2013, p. 80), “[...] everything in it [in the boarding school], unlike the indigenous solidarity, was individualized”.

The boarder received clothing items for ordinary days and festive events (civic and religious), which should be returned at the end of the year. According to a former female student, in the girls’ boarding school “[...] there was a rustic garment for each student, which had to be worn mandatorily at the bath time in the river and in a stretch out of the boys’ sight. The nuns taught the girls techniques for them to change clothes without showing their own bodies”. In addition to the covering of the body during the baths, the mandatory use of the uniform brought the underlying idea that uniformity of garments should be accompanied by uniformity of behavior and by submission to hierarchical superiors.

Depending on age, the boarder was appointed to be part of groups (older, intermediate and younger), from which they should not separate, a procedure that takes us back to the Goffmanian concept of socialization, in which individual identity is diluted and overlaid by the joint action of the members. As for manual work, the intermediate and younger groups were responsible for working in the fields, while the older ones were apprentices in woodwork, carpentry and tailoring workshops. According to Blanco (n.d., p. 95), “[...] on the very day a new student joins our community, he receives his hoe and, at the time of agricultural work, goes to the field. He carefully study the movements of his mates and imitates them in everything. [...] What they like most is going to the woods, mowing, or chopping firewood”.

Imitation was taken as one of the characteristics of the indigenous personality used for learning. Regarding learning in the workshops, according to Blanco (n.d, p. 96, our emphasis),

[...] the Indians, with methodical education, are capable of learning any craft, just like us, but not without great sacrifice on the part of the missionaries [...] [since they] are only used to see forests, canoes, bows and arrows, ‘it becomes quite difficult to make them learn other things’. That is why they want to see everything, not just once but many times.

Education ‘for’ and ‘through’ work explains the beliefs about indigenous manual skills to the detriment of the intellect, while, according to Lima (1992), it was believed that work would contribute to operating the ‘transiency of the Indian’ - from indolent to citizens ‘useful’ for the Brazilian nation. As for the virtue of work, the Salesians believed that, in addition to providing physical wellbeing, disciplined work was a source of ‘moral [...] wellbeing’ and that agriculture was the true economic vocation of the Negro River (Às margens do Amazonas, 1941). Within the colonizing project, agriculture thus comprised a list of strategies mobilized towards fighting nomadism and ensuring the sedentarization of indigenous peoples, in order to make it possible to achieve the missionary goals of conversion and civilization.

Regarding the organization of the space, a boarding school student was assigned a site for a hammock in the collective dormitory, a site in the classroom and another in the church, places where the observance of silence was mandatory, with each environment requiring different manners and attitudes as to how one behaved and conducted themself. From the perspective of the ‘civilizing process’ (Elias, 2011; Gélis, 2008), the inculcation of ‘good manners’ aimed to conform the apparent attitude and the very inner side of the individual.

For Foucault (2009), disciplinary power rationalizes the space in order to nullify desertion, vagrancy and agglomeration. Space control was used to identify the undisciplined ones, those who evaded surveillance, often with the complicity of colleagues, to, for instance, scare girls at night in the girls’ dormitory. In this case, when the wrongdoing was discovered, the assistant would immediately collect the empty hammocks in the dormitory in order to identify the troublemakers, forcing them to turn themselves in and receive punishment, such as expulsion from the boarding school (Missão Salesiana do Içana, 1964).

About the organization of time, time fragmentation, the obligation to experience it with precision, application and regularity aimed to prevent idleness and, simultaneously, guarantee the training of the body, from the synchrony of the latter with gestures and objects, the quality and usefulness of time (Foucault, 2009). Time control was made possible through a daily schedule, which encompassed the totality of the actions and interests of the boarders in the institutional routine.

In short, the daily schedule, going from 6:30 to 21:00, was structured around four main activities: studies, religious practices, manual work, and leisure. Active participation in leisure was mandatory, so the assistant was careful to make sure that no one was absent from games and plays. Leisure, in addition to a physical and mental benefit, helped with discipline, as a Salesian advised: “[...] I recommend always keeping breaks entertaining, with organized games, so that the boy goes into the classroom tired, and discipline becomes lighter” (Missão Salesiana São Gabriel da Cachoeira, 1962, p. 1). Most activities in the boarding school required physical or mental effort, concentration and seriousness, that is, upon entering the boarding school, the student began to take on the responsibilities of an adult, leaving behind the spontaneous and free life of the villages (Ferreira, 2007).

Time control expressed a complex organization and an articulated stratification of educational work in which the primary function of the ‘assistant’ was surveillance. The assistant is the inspector of the boarders at all times and places, from dawn until dusk. At the beginning of the boarding schools, the missionaries were the assistants. As the first students completed primary education (4th grade), some of them were recruited to act as their ‘helpers’, especially those who had excelled in studies, behavior, piety, and work during their boarding school years. Therefore, the assistant in the boarding school was compared to a boss’s ‘foreman’ in extractivism (Peres, 2013).

This strategy facilitated the Salesian work, since, on the one hand, the missionaries distanced themselves from the direct exertion of control, transferring it to subordinates, in order to alleviate the students’ antipathy due to the application of punishments and, in this way, dedicated themselves to the role of counselors, confessors, spiritual guides, parents and friends, in short, functions that would bring them amicably closer to the boarders, in order to gain their confidence. On the other hand, the native assistants, having experienced the boarding school regime and knowing the indigenous sociocultural reality and psychology, created effective pedagogical devices to place the students under the regime of obedience and order, thus ensuring the achievement of the institutional objectives.

The recruitment of native assistants increased due to a shortage of Salesians, worsened by the crisis of vocations on the European continent as of the 1960s, and by the fact that the minority of missionaries spoke Tukano, a situation that made it impossible to communicate with novice students, who did not know how to speak the Portuguese language.

Surveillance was also favored by the architecture of the boarding schools, based on the style of monastery cloisters, which were built in semicircular or rectangular lines with internal collective environments and, externally, designed with porticoes, a recreational space in the center allowing the assistant to have a complete view from any angle, along the lines of the ‘Panopticon’, namely, the centrality of the inspector and the ‘seeing without being seen’ (Bentham, 2008). The surveillance of the boarders went beyond the boarding school and was entrusted to village catechists during the students’ vacation period.

Mister Catechist from [location name], in the week of 20-27 of June the boys of your village can go back to their homes for a few days of vacation. [...]. I ask you to take notes, on this sheet, about the behavior of each of the boarders in your village on these days: work, parties, prayer frequency, etc. (Missão Salesiana de Iauareté , 1971).

Associated with surveillance, exams are, according to Foucault (2009), a ritualized normalizing control that combines the ceremony of power, the formation of experience, the demonstration of strength, and the establishment of the truth. In boarding schools, exams produced fear and trembling in the boarders and were surrounded by rituals of knowledge and power. The local authorities were invited to the final exams, which consisted of a written and an oral part.

In the 1950s, the written Portuguese exam for students from 1st to 5th grade consisted of dictation, lexical analysis, verb conjugation, and composition, while the arithmetic exam included the four operations, as well as ordinary and decimal fractions (Colégio São Gabriel, 1950-1955). The written exams show that, on the one hand, the Portuguese and Mathematics contents were based exclusively on the knowledge of the non-indigenous society, which, therefore, could be taught in any school within the national education network, and, on the other, excluded the cultural knowledge of indigenous populations.

Regarding the recording of information, observations on the behavior of the boarders were written down on an individual sheet, which was updated throughout the year. On said sheets, the depreciations concerning the boarder outweighs the praises because, when the latter are recorded, they appear generically as ‘good student’ and ‘intelligent’ (Colégio São Gabriel, 1952-1965). Most of the observations refer to disobedience to the missionaries, and to transgressions of the boarding school rules. The information record served as the basis for the annual awards system, the expulsion of students, and for the selection of candidates for religious and priestly life.

Another mechanism of disciplinary power was the requirement of learning Portuguese and abandoning native languages. The Salesians implanted the idea that speaking the indigenous language was an obstacle to learning the Portuguese language, contributing to three situations happening in the Negro River at the end of the 1980s: [a] the child knows how to speak the indigenous language, but does not use it; [b] the child only understands the language and the speech; [c] the child does not know the language (Renault-Lescure, 1990). In these situations, it is reasonable to assume that the prohibition of indigenous languages in public environments caused the reflux of indigenous languages to the domestic sphere (home, work, parties), as these were environments where, despite surveillance, missionary interference arrived weakened and, in this way, they became opportune spaces for the exertion of resistance.

The imposition of the Portuguese language as the only language of communication contrasted with the linguistic diversity of the Negro River and was anchored in the ethnocentric vision of the missionaries, who conceived their own languages as superior to the indigenous ones. Due to linguistic exogamy, a couple belongs to different linguistic groups, which causes, at the very least, the child to learn two languages: the father’s and the mother’s; the Portuguese language and, eventually, Nheengatu and Spanish are added to those. However, despite the imposition of the monolingual tradition, indigenous populations did not allow linguistic diversity to submerge into the monolingualism of the national language (Sorensen & Arthur, 1983).

The deleterious consequences of the imposition of monolingualism become clearer when we consider the relationships between language and identity construction, that is, that language is one of the elements that organizes the perception of the world and, in the case of the Eastern Tukano, it is one of the “[...] basic factors for the construction of their social identity, as it marks the condition of member in more inclusive named and exogamous groups [...] it is the criterion for establishing and expressing consanguinity relationships” (Chernela & Leed, 2002, p. 469). Thus, with language being an indicator of group affiliation and, therefore, of identity specificities and differences, it constituted an obstacle to missionary goals, which meant stripping the boarders of their cultural and social identities, that is, the language was not respected as a constitutive element of indigenous identity.

In the boarding school, monolingualism followed deadlines because, after a certain period of tolerance for the use of the Tukano language, granted only to novice students, the use of Portuguese was mandatory. The adoption of the Tukano language by the Salesians for the development of missionary activities, the requirement for students of other ethnicities to learn Tukano, and the curricular teaching of this language in Salesian schools, as of the 1970s, reinforced a broad process that was underway and that resulted in the adoption of the Tukano language by most linguistic groups (Oliveira, 2007).

In which situations was the use of the Tukano language tolerated within the boarding school? According to a graduate from Iauareté, novice students spent most of their time in silence, as they did not master the Portuguese language. During the early years, novice students’ communication was drastically reduced to what was strictly necessary, and even so, they approached the assistant or a senior student of the same ethnicity in a reserved manner to communicate their needs.

When the principal of the boarding school needed to deal with a novice student, the assistant mediated the meeting: the principal would express his reprimands in Portuguese, which would be translated by the assistant to the student, or the principal would write the admonishment in Portuguese, and the assistant would translate it for the offender. We close this topic with the statement of a Tukano graduate, according to which “[...] the easiest way to kill an indigenous person is to exterminate their identity and their language. Without identity and without language, a people is dead” (Ferreira, 2007, p. 114).

Infractions of the regulation norms in the institutional daily life were punished with penalties. The latter are, according to Foucault (2009), constituted by a sanction-reward system and function as resources for good training. The ideology of disciplinary power was psychologically introjected into the boarders, in such a way that the occurrence of infractions was reported by one’s own mates. The identification of offenders by hierarchical superiors was obtained through institutional devices, including whistleblowing, which, in its turn, was a result of the institutional coercion that undermined individual autonomy and collective self-determination (Douglas, 2007). The chronicle of the Salesian Mission of Iauareté (1933b, author’s emphasis) records

[...] yesterday’s thief [5/7] is placed today, after the Holy Mass, in an external corner of the dining room decorated with flour and pieces of roasted pork. In each hand he holds a piece of roasted pork, on his back he carries a large sign, an identical one serves as a breastplate to protect his chest, a pair of trousers with flour hangs around his neck as if it was a tie. The signs say the reason for their decorations with just one word: ‘thief’. Both schools [boy’s and girl’s] and some people parade in front of [Name], who, due to his cleverness, today is given another important title, that of thief.

Sanctions included food deprivation, increased manual work, standing beside the hammock, in the classroom or in the courtyard, splitting and carrying firewood, deprivation of parental visit, suspension from sports, theater and outings, apologizing in public, repeatedly copying ‘I will not speak Tukano anymore, only Portuguese’, etc. Indiscipline was dealt with rigorously, sometimes with expulsion, as it was about imposing rules and a life pace of which indigenous children were unaware, but to which they had to submit.

In the mission on the Içana river, probably due to conflicts between Catholics and Evangelicals, the Salesians faced greater resistance to implementing the missionary project and even dealing with the Baniwa, so the length of the boy’s boarding school was ephemeral (1962-1967), and the number of boarders was always lower than that of the establishments on the Uaupés and Tiquié rivers due to parents refusing to enroll their children. In that mission, some parents decided to take their children out of the boarding school for disagreeing with the punishments applied to the students and, in particular, ‘due to mistreatment on the assistant’s part’, sanctions that the Salesians deemed necessary because they were disorderly students (Missão Salesiana do Içana, 1965).

Because of the punishments, obedience was obtained through intimidation. The fear of suffering punishment was the motive that determined the behavior of indigenous children and standardized collective actions - “[...] we behaved out of fear [...]”, revealed a graduate from the Iauareté mission. The reiteration of institutional values made the boarder believe that failures in the boarding school life (studies, behavior, piety) were their sole responsibility, as a runaway student reports: “Father Principal, I am leaving because I misbehave” (MI, 1965).

The analysis of discipline in the institutional daily life shows the boarders’ inadaptability and resistance to the subjection imposed by hierarchized relationships and to the lifestyle in the boarding school regime, manifested in various ways, such as acts of indiscipline, dropout, ‘outings’ and runaways. Regarding dropouts, the students communicated to their parents or relatives their dissatisfaction with the boarding school and their desire to come back home, which, in general, was agreed upon by their parents. The outings, as the Salesians said, consisted of the fact that the boarders took advantage of their parents’ visit to accompany them on their trips to other locations, thus freeing themselves from the routine for a few days - attitudes that displeased the Salesians, who rebuked the parents for not forcing their children to stay in the boarding school: “The father of boarder [Name] asks permission to take his son for an outing in São Gabriel. The permission is denied. However, in these lands, the children are the bosses. Therefore, our [Name] did what pleased him by going for an outing with his father” (MI, 1933a).

The concept of paternal authority claimed by the Salesians was based on the coercive power of parents over their children, but for Overing (1995, p. 131), the hierarchical principle is not generalized in the Amazon, as “[...] the fact of linear time not occupying a prominent position in its theories on reality means that the concept of time is not considered naturally relevant to social theory and practice”. The aforementioned indigenous ethnographers have emphasized that indigenous education is founded more on the ‘art of persuasion’ than on imposition, that is, parents cautiously exert direct control over their children. The non-coercive power of parents was also manifested in not creating problems when their children decided to risk a more drastic decision against the boarding school regime: running away. The reasons for the escapes (e.g., dissatisfaction with reprimands, fear of falling ill, fear of injections) can be summarized in the impact caused by the contradiction between the boarding school regime and the village life.

Many of those who ran away - and some did so more than once - were brought back when captured by senior students, who were called out by missionaries to track down deserters. In other situations, the parents or relatives themselves brought their child back to the boarding school for believing in the benefits of schooling and for fearing retaliation from the missionaries. Thus, many boarders aborted their escape plans for fear of harming their parents, as some of them had roles assigned by the missionaries (captain, catechist, teacher) and, if they did not return the fugitive son, they could suffer reprisals, such as deprivation of the goods provided by the Mission because of the fugitive son, as reported by Rezende (2007):

The inadequacy of the boarding school regime, whether for individuals, whether for indigenous populations in general, gives us the possibility of dealing with the case of the boarders belonging to the Maku language family, who were more resistant to the reclusive life of the boarding school.

Among the ecological, linguistic, cultural, economic and social traits of the Maku, we can highlight them living in interfluvial areas (forest Indians), endogamy (marriage between a man and woman of the same language), the fluidity of social organization, nomadism, hunting, harvesting, bilateral residence with a tendency to uxorilocality (displacement of the man to his wife’s tribe), distribution, composition and interaction between groups (domestic, local and regional), kinship rules, the system of clans, and cosmology. (Pozzobon, 1983; Silverwood-Cope, 1990).

These aspects of the Maku culture contrast with the characteristics of the Eastern Tukano and Aruak language families, such as riverbank housing (river Indians), language exogamy (marriage between a man and a woman of different languages), tendency to sedentarism due to residence in large malocas, agriculture, fishing, and patrilocal residence (displacement of the woman to her husband’s tribe). The Maku’s sociocultural specificities define, for the other ethnicities (the river Indians), the Maku status, namely, that of being an inferior ethnicity in the social hierarchy, or even non-human, close to the category of animals, due to their hierarchical dependence and internal social organization (Silverwood-Cope, 1990).

The summary description of the Maku cultural traits provides elements for understanding the Maku’s greater resistance to the missionary action. Attempts at nucleating, catechizing and schooling the Maku, put into practice by the Salesian Missions, did not have the same effects as those seen in the Tukano Orientale Aruak language families, especially due to the Maku’s resistance to contact with the whites, which was expressed through social-geographic isolation and their refusal to abandon nomadism, in such a way that “[...] they escaped the direct impact of the missionary influence and became a reservoir of many traits of the indigenous culture that the Indians of the River, who consider themselves ‘civilized’, have abandoned” (Silverwood-Cope, 1990, p. 72, author’s emphasis).

In its turn, the Maku’s refusal to the reclusive life in the boarding school was an extension of the more general resistance about which we have talked, as the students of this ethnicity rarely completed their study cycle, according to this report:

During the night, the three Maku students we had ran away. They had already been in the Mission last year [1959]. This year, we had five from this tribe. In previous years, we had some [sic], but some ran away soon, others ran away in the 2nd year or went on vacation and did not return. Only one Maku, already with his family, [...] stayed in the Mission until finishing 4th grade (MI, 1960).

Associated with these contradictions between the boarding school regime and the autochthonous cultures was the fact that the relationships of the indigenous populations of the Uaupés region with the Maku are hierarchical relationships in which the latter, due to their specific cultural characteristics, are considered inferior, ‘servants’ or slaves. For this reason, Maku students were discriminated against and despised in the boarding schools by students of other ethnicities, which thus contributed to them running away (Hohenscherer, n.d., p. 13).

The description and analysis of some events and disciplinary devices linked to the day-to-day of Salesian boarding schools for indigenous children lead us to observing that these educational experiments reproduce the institutionalization processes of social life as a whole, a disciplinary strategy that predates the modern age but that, in modernity, reaches a high level of sophistication as to the coercive mechanisms through which full control over the life of individuals and of social groups is intended.

Further considerations

Resuming the objective of our study, namely, describing and analyzing institutional strategies for disciplining indigenous children, particularly the interdiction of indigenous languages, sociocultural segregation and the imposition of the Portuguese language, allows us to postulate that the action of the Salesian missions is attuned to the colonizing undertaking, as these missionary practices reveal the asymmetrical character of the hierarchical social relations between the missionaries and the indigenous populations.

In terms of pedagogical ideas and practices, the boarding schools, considering separation by sex, the punishments, the emphasis on religious education, and surveillance contrasted with the educational principles of the New School (publicity, one-room school, secularity, gratuitousness, compulsory enrollment, co-education, freedom). In its turn, the incipient presence of the State, limited to the granting of subsidies to the church and the work of the SPI, and the inexistence of legislation on indigenous school education, enabled the hegemony of the Catholic Church over indigenous educational contexts in relation to the ideals of the renovators and of the public policies of the Brazilian State.

The education received during the years of confinement in the boarding school regime was gradually forged in indigenous children, based on the ideology of nationality as culturally homogenized by language and customs, therefore consisting of unified identities, a new conception of themselves, a new view of the world and of standards of living, no longer referenced in the culture of origin, but in the culture of white people. These new conceptions gave rise to doubts, or even rejection, about the way of life in the villages, the education received from parents, and launched many boarding school graduates into the lifestyle of the ‘civilized’ ones, since, as previously highlighted by Sõãliã, the graduates “[...] are interested in assimilating to the global society’s way of life”.

However, the strategies of the Salesian hegemonic power did not determine the complete resignation of the indigenous populations, as it seems to be denoted by a certain interpretation of disciplinary power and of total institution, since, in opposition to them, the agents’ tactical activism was articulated, be it of an individual order (acts of indiscipline, escapes from the boarding school), a collective order (the refusal of many parents to return their runaway children, withdrawal from the boarding school), and a societal order (the Maku’s refusal to settling and schooling).

With regard to the views of graduates and Salesians, the latter, in general, positively evaluate the boarding school regime, particularly schooling, education through work, the learning of moral and religious values, the pedagogical value of punishments, while graduates weigh the benefits with critical stances on institutionalization, as it caused the interruption of traditions, the replacement of indigenous education with school education, the loss of free and spontaneous life in the villages, and the emphasis on individualism at the expense of indigenous solidarity, which denotes that perspectives on Salesian education are not univocal.

In this sense, we can speak of the contradictory character of boarding school education, which evidences the limits of the Salesian pedagogy and reveals that, on the one hand, the Salesian educational dynamic promoted the subjugation of indigenous cultures, but, as it can be grasped from the Indigenous texts used in this study, this same westernized educational heritage served as the basis on which the critical thinking and resignification operated by the graduates were built for them to break with the tutelage and assert their right to citizenship, to self-determination, that is, in order to manage the conflicts of interest arising from the Western and Christian civilizing process.

The results and conclusions of this research article do not deplete the senses and meanings involved in the intersociety relations between Salesians and indigenous societies, but we postulate that the action of boarding schools was the strategy by which the devices of power and knowledge of the Salesian pedagogy reached greater depth and durability in the indigenous imagination, being, in our view, emblematic of the identity construction of generations of Salesian mission graduates, an object that demands further research and analyses.

REFERENCES

Colégio São Gabriel. (1950-1955). Livro vida escolar. [ Links ]

Colégio São Gabriel. (1952-1965). Livro vida escolar. [ Links ]

">Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1933a, 4 de julho). Crônicas. [ Links ]

">Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1933b, 6 de julho). Crônicas. [ Links ]

">Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1960, 23 de março). Crônicas. [ Links ]

">Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1965, 25 de agosto). Crônicas. [ Links ]

Missão Salesiana do Içana (1971, 20 de junho). Carta. [ Links ]

Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1962). Crônicas. [ Links ]

Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1964, 4 de julho). Crônicas. [ Links ]

Missão Salesiana do Içana. (1965, 3 de maio). Crônicas. [ Links ]

Relatório apresentado à Intendência Municipal de São Gabriel da Cachoeira pelo Exmo Snr. Dr. Madail Gonçalves, superintendente municipal, por occasião da instalação dos seus trabalhos em 1º de outubro de 1923 e Lei n. 9, de 8 de outubro de 1923, que orça a receita e fixa a despeza do município de São Gabriel para o ano de 1924. (1923). [ Links ]

Relatório lido pelo prefeito municipal, em comissão, Dr. Arnoldo Carpinteiro Péres, na reunião ordinária da intendência municipal de São Gabriel, no dia 16 de abril de 1929. (1929). [ Links ]

Ariès, P. (1981). História social da criança e da família (2a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: LTC. [ Links ]

Bentham, J. (2008). O panóptico (2a ed.). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Blanco, M. (n.d.). Inferno verde. Porto, PT: Oficinas Gráficas do Colégio dos Órfãos. [ Links ]

Cabalzar, A., Ricardo, C. A. (2006). Povos indígenas do Rio Negro: uma introdução à diversidade socioambiental do noroeste da Amazônia brasileira (3a ed. rev.). São Paulo, SP: ISA. [ Links ]

Chernela, J. M., & Leed, E. J. (2002). As perdas da história. Identidade e violência num mito Arapaço do Alto Rio Negro. In B. Albert & A. R. Ramos. Pacificando o branco: cosmologias do contato no norte-amazônico (p. 469-486). São Paulo, SP: UNESP. [ Links ]

Costa, M. G. (2012). A Igreja católica no Brasil: as ações civilizatórias e de conversão ao catolicismo das missões salesianas junto aos povos indígenas do alto Rio Negro (1960-1980) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. (2007). Como as instituições pensam (1a ed.). São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Elias, N. (2011). O processo civilizador: uma história dos costumes (Vol. I, 2a ed.). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Zahar. [ Links ]

Falcão, J. A. F. (2008). A educação salesiana no internato de Barcelos analisada à luz do sistema pedagógico salesiano e da visão de ex-aluno (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus. [ Links ]

Ferreira, G. V. (2007). Educação escolar indígena: as práticas culturais indígenas na ação pedagógica da Escola Estadual Indígena São Miguel/Iauaretê (AM) (Dissertação de Mestrado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica, São Paulo. [ Links ]

FOIRN/UNIRT. (2006). Bueri Kãdiri Marĩriye: os ensinamentos que não se esquecem / narrador Diakuru (Américo Castro Fernandes); intérprete Kisibi (Durvalino Moura Fernandes). São Gabriel da Cachoeira, AM. [ Links ]

Fontoura, I. F. (2006). Formas de transmissão de conhecimento entre os Tariano da região do Uaupés - AM ( Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1979). Microfísica do poder. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Graal. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (2009). Vigiar e punir: nascimento da prisão (37a ed.). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Francisco, A. J. (2010). Educação & modernidade: os salesianos em Mato Grosso 1894-1919. Cuiabá, MT: Entrelinhas: EdUFMT. [ Links ]

Freire, J. R. B. (2011). Rio Babel: a história das línguas na Amazônia. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: EdUERJ. [ Links ]

Gélis, J. (2008). O corpo, a Igreja e o sagrado. In A. Corbin , J-J. Courtine & G. Vigarello. História do corpo: da Renascença às luzes (p. 19-130). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Goffman, E. (2005). Manicômios, prisões e conventos. São Paulo, SP: Perspectiva. [ Links ]

Goldman, I. (1948). Tribes of the Uaupés-Caqueta Region. In J. H. Steward (Org.), Handbook of South American Indians (Vol. III). New York, NY: Cooper Square Publishers. [ Links ]

Hohenscherer, N. (n.d.). História da evangelizção dos Maku de Pari-Cachoeira. Manaus, AM: Inspetoria Salesiana Missionária da Amazônia/ISMA. [ Links ]

Lima, A. C. S. (1992). O governo dos índios sob a gestão do SPI. In M. C. Cunha. História dos índios no Brasil (p. 155-172, 2a ed.) São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Luciano, G. J. S. (2006). “Projeto é como branco trabalha; as lideranças que se virem para aprender e nos ensinar”: experiências dos povos indígenas do alto rio Negro (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Luciano, G. J. S. (2013). Educação para manejo do mundo: entre a escola ideal e a escola real no Alto Rio Negro. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Contracapa, Laced. [ Links ]

Às margens do Amazonas. (1941). (Leituras Católicas de Dom Bosco, ano LI, nº 619). [ Links ]

Nakata, C. (2008). Civilizar e educar: o projeto escolar indígena da missão salesiana entre os Bororo do Mato Grosso (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Novaes, S. C. (1993). Jogo de espelhos: imagens da representação de si através dos outros. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Oliveira, A. (2007). Etnomatemática dos Taliáseri: medidores de tempo e sistema de numeração (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife. [ Links ]

Overing, J. (1995). O mito como história: um problema de tempo, realidade e outras questões. Mana, 1(1), 107-140. [ Links ]

Peres, S. C. 2013). A política da identidade: associativismo e movimento indígena no Rio Negro. Manaus, AM: Valer. [ Links ]

Pozzobon, J. (1983). Isolamento e endogamia: observações sobre a organização social dos índios Maku (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. [ Links ]

Renault-Lescure, O. (1990). As línguas faladas pelas crianças do Rio Negro (Amazonas): descontinuidade na transmissão familiar das línguas. In H. B. Franco & M. F. M. Leal (Org.), Crianças na Amazônia: um futuro ameaçado (p. 315-324). Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará. [ Links ]

Rezende, J. S. (2007). Escola indígena municipal Ʉtãpinopona Tuyuka e a construção da identidade Tuyuka (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Campo Grande. [ Links ]

Rizzini, I. (2004). O cidadão polido e o selvagem bruto: a educação de meninos desvalidos na Amazônia imperial (Tese de Doutorado), Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Rizzini, I. (2006). Educação popular na Amazônia Imperial: crianças índias nos internatos para educação de artífices. In P. M. Sampaio & R. C. Erthal (Orgs.), Rastros da memória: histórias e trajetórias das populações indígenas na Amazônia (p. 133-170). Manaus: EDUA. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, A. D. (1986). Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo, SP: Loyola. [ Links ]

Santos, B. S. (2019). O fim do império cognitivo: a afirmação das epistemologias do sul (1a ed.). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Saviani, D. (2008) História das ideias pedagógicas no Brasil. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados. [ Links ]

Silva, E. L. (2010). O binômio missão-educação em documentos da Igreja Católica a partir do Concílio Vaticano II e no Projeto Educacional da Sociedade Salesiana (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus. [ Links ]

Silverwood-Cope, P. L. (1990). Os Makú: povo caçador do noroeste da Amazônia. Brasília, DF: Editora Universidade de Brasília. [ Links ]

Sõãliã, W. B. (Dorvalino Chagas). (2001). Cosmologia, mitos e histórias: o mundo dos Pamulin Mahsã Waikhana do Rio Papuri (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife. [ Links ]

Sorensen, J., & Arthur, P. (1983). El surgimiento de un regionalismo Tukano: presiones políticas. América Indígena, XLIII (4), 785-795. [ Links ]

Stella, P. (1968). Don Bosco nella storia della religiosità cattolica (Volume primo: vita e opere). Zurich, CH: PAS-VERLAG. [ Links ]

Umúsin, P. K., & Tolamãn, K. (1980). A mitologia heróica dos índios Desâna. Antes o mundo não existia. São Paulo, SP: Livraria Cultura Editora. [ Links ]

Viveiros de Castro, E. (2002). A inconstância da alma selvagem e outros ensaios de antropologia. São Paulo, SP: Cosac Naify. [ Links ]

Weigel, V. A. C. (2000). Escola de branco em maloka de índio. Manaus, AM: Editora da Universidade do Amazonas. [ Links ]

Received: August 01, 2020; Accepted: January 08, 2021; Published: June 25, 2021

texto em

texto em