Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.21 Maringá 2021 Epub 02-Jul-2021

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v21.2021.e188

Orignal article

Maria de Lourdes Nogueira: the course of a libertarian teacher and writer

1Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais, Carangola, MG, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil.

This article focuses on the course of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, who, in the 1920’s, stood out for her libertarian nature publications in magazines and press, and acted in the Anarchist Movement. In the 1930’s, she entered the teaching staff of Colégio Pedro II, then mostly composed of men. In the perspective marked by Ginzburg (2006) the sources were questioned in the sense of mapping the ways she went through and the relationships she set up, in order to understand the strategies she used and the changes that made her insertion possible at CPII. The theoretic support that allowed denaturalizing the feminine subordination was Perrot (2012), Saffioti (2013) and Louro (2007), and dialoguing with the anarchist women course: Rago (2012), Martins (2009, 2013) and Fraccaro (2018).

Keywords: high school; professional career; anarchist women

Este estudo foca o percurso de Maria de Lourdes Nogueira que, na década de 1920, destacou-se por suas publicações de cunho libertário em revistas e na imprensa, e atuou no Movimento Anarquista. Na década de 1930, ingressou no corpo docente do Colégio Pedro II, então constituído majoritariamente por homens. Na perspectiva assinalada por Ginzburg (2006), as fontes foram interrogadas no sentido de mapear os caminhos que ela percorreu e as relações que estabeleceu, a fim de compreender as estratégias que ela utilizou e as mudanças que viabilizaram sua inserção no CPII. O aporte teórico que permitiu desnaturalizar a subordinação feminina foi Perrot (2012), Saffioti (2013) e Louro (2007), e dialogar com a trajetória de mulheres anarquistas: Rago (2012), Martins (2009, 2013) e Fraccaro (2018).

Palavras-chave: ensino secundário; carreira docente; mulheres anarquistas

Este estudio se centra en la trayectoria de Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, quien, en la década de 1920, se destacó por sus publicaciones libertarias en revistas y periódicos y por ser miembro del Movimiento Anarquista. En la década de 1930, ella pasó a formar parte del cuerpo docente mayoritariamente masculino del Colégio Pedro II. En la perspectiva destacada por Ginzburg (2006), se cuestionó a las fuentes para mapear los caminos que ella tomó y las relaciones que estableció, con el fin de comprender las estrategias que utilizó y los cambios que hicieron posible su inserción en CPII. El aporte teórico que permitió desnaturalizar la subordinación femenina fue Perrot (2012), Saffioti (2013) y Louro (2007), y dialogar con la trayectoria de las mujeres anarquistas Rago (2012), Martins (2009, 2013) y Fraccaro (2018).

Palabras clave: enseñanza secundaria; carrera docente; mujeres anarquistas

Introduction

This article provides some reflections on the course of anarchist writer and teacher Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, pointing out the conditions and circumstances that led her to teach at Pedro II School [Colégio Pedro II] (CPII), a secondary education institution, whose teaching staff was composed exclusively of male teachers.

Said institution was intended exclusively for boys and recognized by society since its creation, in 1837, with a teaching staff of ‘remarkable knowledge’, made up of regular teachers, who were appointed by the Ministry of the Empire and “[...] who graduated from traditional European universities or in the Empire’s Law, Medicine and Engineering courses - ‘public men’ shaped by the European paradigms of civilization and progress” (Andrade, 2016, p. 105, author’s emphasis).29

Women would only have a place as educators, in the 1920s30, in the condition of supplementary or assistant teachers. This is the case of teacher Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, who worked as of 1927 with the Portuguese supplementary class, being one of the first women to join CPII’s teaching staff.

The analysis of her journey was not only based on the work she developed in this institution, but also sought evidence in the sources of elements about her training, her activity in other public spaces, such as associations, societies, educational establishments, unions, press, among others.

Thus, this article is comprehended within the studies on the history of women in Brazil and Latin America, which, as pointed out by Gonçalves (2006), developed in the 1990s already, in Brazil, culminating in the release of ‘History of Women in Brazil’ [História das Mulheres no Brasil], organized by Mary Del Priori and published in 2001. These studies were linked to the discussion on the use of the gender category, although, on the pages of this publication, there is no title dedicated to anarchist women. Nevertheless, the contribution of these studies to problematize the power expressed in gender relations and denaturalize female subordination cannot be ignored, such as Guacira Lopes Louro (2007), who brings this discussion to the educational field, in the aforementioned work.

To reflect on the conditions and circumstances that led women to take the classrooms, it is important to think that this story permeates the matter of gender, in order to explain the ways in which men and women formed their identities and built their practices, intervening in the representations they were given. In this sense, the studies by Marinho (2016) note the specificity and protagonism of the feminist movement in broadening the role of women, not only in the professional and social fields, but also in the educational field. The studies by Rago (2012), Martins (2009, 2013) and Fraccaro (2018), in their turn, enable a dialogue with the course of female anarchist activists, even though they did not focus on the journey of female teachers and their role in the educational field, as intended in this work.

Thus, this article is invested with importance for contributing to studies in the History of Education field and on anarchist women and their participation in the social and political struggles of the 1920s, presenting the path taken by teacher Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, who taught in the secondary course of CPII’s Day school, with the supplementary Portuguese class. Her personal story, in the sense approached by (Ginzburg, 2006), brings, in its constitution, characteristics of the society to which she belongs, but also expresses what makes her unique and different from the other individuals who are part of this same society, being understood as a network of interdependencies.

In addition to her teaching job, as Maria de Lourdes communicated her anarchist ideals through literary works and the press, being directly linked to the Anarchist Movement, we can place her in the new category of scholars, created by Gomes and Hansen (2016), as an intellectual cultural mediator. From this perspective, the individuals who produce knowledge and communicate ideas can be directly or indirectly linked to the social-political intervention, being treated as strategic elements in the cultural and political fields for being in a position of recognition in social life. Thus, this category starts to include women who worked as writers, teachers and authors, and learning about their experiences, journeys and intellectual strategies becomes necessary (Gomes & Hansen, 2016).

In the first surveys carried out in the NUDOM - Núcleo de Documentação e Memória [Pedro II School’s Documentation and Memory Center], three women who worked at the Day school as teachers of supplementary classes were found: Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, for Portuguese; Aimée Ruch, for French, and Maria da Glória Ribeiro Moss, for Chemistry; in addition to Carmem Velasco Portinho, who worked as an arithmetic assistant at the Day school from 192731. However, as other studies on the presence of women at CPII have already pointed out, women entered the institution as students initially, with the first class of girls in the school starting in 1927 (Alves, 2009; Marinho, 2016).

Of the three teachers who worked at CPII with the supplementary classes that year, the focus will be on the course of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, an activist for the Anarchist Movement in the first decades of the 20th century, in Rio de Janeiro.

The text is divided into three sections, besides this introduction. In the first section, we present the aspects that allowed her to join CPII’s teaching staff, as of Euclides Roxo’s direction. In the second section, we describe Maria de Lourdes Nogueira’s role as an activist for the Anarchist Movement in Rio de Janeiro, and as a writer and a poet. In the third section, we address her teaching work at CPII. Finally, as further considerations, we highlight the contributions that this type of approach to one’s individual journey can bring to the field of the history of anarchist women in Brazil and Latin America and to the History of Education field.

Maria de Lourdes Nogueira’s admission to and work in the teaching staff of cpii

In the 1920s, Pedro II School underwent several reforms in its teaching program, promoted and encouraged by the then principal of this establishment, Euclides de Medeiros Guimarães Roxo. Among the changes that took place, we can mention: increase in the number of students, including non-paying ones, and, with that, the expansion of supplementary classes; admission of women as students and the role of the Feminist Movement, led by Bertha Lutz32, which advocated for the inclusion of women in the student body; the link between academic training and the subject taught; and the appointment, by regular teachers33, of the chairs of modern languages and sciences to female teachers, for the latter to work with these supplementary classes.

From the studies by Soares (2014), it can be inferred that the main door for women to secondary teaching, at the institution, was cla sses of modern and mother tongues, especially supplementary classes of Portuguese, English and French.

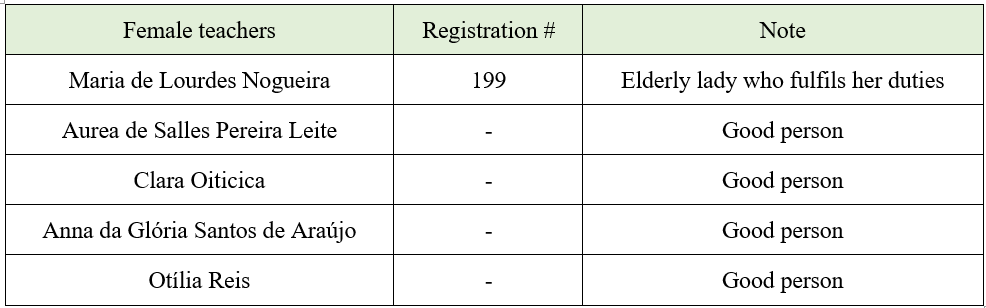

Source: Soares (2014).

Table 1 Teachers of the supplementary Portuguese classes at Pedro II School - 1940.

In Table 1, we can see that among the five female teachers, only Maria de Lourdes Nogueira had a teacher registration with the DNE, under registration No 199, being described as ‘an elderly lady who fulfils her duties’. In the case of the other teachers - Aurea de Salles Pereira Leite, Clara Oiticica, Otília Reis, Anna da Glória Santos de Araújo -, only the expression ‘good person’ appeared in front of their names. A hypothesis on the different treatment of Maria de Lourdes is that this evaluation detached her professional image, in the sense of following institutional norms, from activism.

It cannot be ignored that the broader access, both for non-paying students34 and for female students and teachers, came with a certain precariousness as to the work, since most female teachers were not registered with the DNE, and each regular teacher would be assigned up to four supplementary classes.

This perspective supported on the idea of crisis of school institutions and repercussions on the teaching work, developed by Dubet (2002, 2011) and presented by Soares e Silva (2018), indicates that the Capanema Reform intensified CPII’s institutional crisis, which began in the previous decade with the Francisco Campos Reform, due to problems concerning infrastructure, low wages, increased number of students and supplementary classes, and the creation of the Philosophy course to train higher-level teachers. On the other hand, it allows thinking about the identity strategies built within CPII, as it draws the researcher’s attention “[...] to the processes of individual and collective construction of teaching identities [...]”, revealing elements about “[...] the political constraints, the social interactions and the symbolic dimensions that permeate the identity dynamics of this professional group” (Xavier, 2014, p. 832).

The emphasis on the dichotomy and on the hierarchy between men and women in the processes of teaching-identity construction links the institutional crisis and the decline in the prestige of CPII to the female presence in its teaching staff, limiting the autonomy of individual choices by suggesting that the positions were only filled by women because they were left by men who went in search of better working conditions. However, studies by Mendonça (2015) on the first teachers at CPII already denounced that temporariness was typical of the institution’s teachers at the beginning of its operation. The study by Lauris Jr. (2009) also brings a speech by teacher José Oiticica, denouncing the hierarchy and precarization of work at the institution in 1922, even before women joined the teaching staff, or before the announced teaching reforms.

2nd Substitutes, in addition to earning less than regular teachers, with the same job, cannot take part in the congregations, that is, they do not collaborate in programs, do not take care of their own interests when at stake. It is an unfair situation, and the same effort as that of regular teachers (apud Lauris Jr., 2009, p. 121).

The assumption that women were admitted to CPII only due to an institutional crisis and loss of prestige also disregards the role of the Feminist Movement in claiming greater space for women in educational institutions, as well as the fact that the female teachers who first worked at CPII were part of a project to modernize secondary education, as well as to expand its gratuitousness and secularity.

Based on the assumption that discriminations hierarchize the categories of belonging within the institution, the gender category dealt with in this study articulates with the studies on relations of power, since the latter is understood as exerted and mutable, and not as dichotomous. Saffioti (2013) points out that the ways in which the cultural meanings that constitute differences are built, giving them sense and placing them inside the hierarchical relations that are established, make room for a notion of gender also permeated by subjective identity.

This perspective allows thinking that women started at CPII as a strategy to distinguish themselves from jobs with a negative social image or a subordinate position, or even those that did not require formal training, being also concerned with the aspects that distinguished them from other women and from each other. The ‘valuing of the self’, which, according to Dubar (2012), comes along with a common professional rhetoric, that is, through identification in the constitution of a positive professional identity, would enable women to plan a career and engage in the secondary-education segment.

Based on these studies, our objective, then, is to point out the social conditions experienced by Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, either as a teacher at CPII or through the collective actions in which she took part, giving visibility to her struggles, conquests in the public and private spaces, in order to take her out of the ‘silence’ in which she was confined, perhaps caused by the ‘silence of the sources’. According to Perrot (2012, p. 17): “Women leave few direct traces, writings or articles. Their access to writing came late”. This was not the case with Maria de Lourdes, as she had a major role in the public space, as an anarchist activist, writer and teacher. However, this was not the reality of most women, and the erasure of her journey at CPII and in the Movement after 1920, especially if we compare her with her contemporaries, such as anarchist teacher José Rodrigues Leite Oiticica, shows that, when it comes to women, “[...] silence weighs more” (Perrot, 2012, p. 16).

According to Martins (2013, p. 33), Maria de Lourdes was “[...] a disciple of José de Oiticica, a teacher at CPII and one of the leaders of the Anarchist Movement, with whom she took Latin and Greek lessons”. Whereas there is production about this male anarchist teacher, little is told about the female anarchist teacher. We found two articles published by Angela Maria Roberti Martins, which were important for this article: the first, entitled ‘The Invisibility of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira: Woman, Activist, Libertarian’ [A invisibilidade de Maria de Lourdes Nogueira: mulher, militante, libertária], published in Emecê, Bulletin of Marques da Costa Research Center [Núcleo de Pesquisa Marquês da Costa], in 2009; and the second, ‘Woman, Free Yourself: Anarchism and Women’ [Mulher liberta-te: o anarquismo e as mulheres], published as a book chapter, in 2013. In the latter, Maria de Lourdes is mentioned as a follower of the “[...] orientations of the anarcho-communism systematized by Kropotkin”35 (Martins, 2013, p. 33). And it is on her engagement and her role in the Anarchist Movement that we will focus next.

Maria de Lourdes Nogueira (18?-1967): a libertarian teacher?

Tracking the professional path of teacher Maria de Lourdes Nogueira was not an easy task. Martins’ study (2009) on the Anarchist Movement in Brazil brought some traces about the participation of women in this movement in the early 20th century.

The words of this author regarding Maria de Lourdes Nogueira are significant when she says that this is “[...] a name that deserves to be (re)found [...]”, as she is “[...] a libertarian woman who was present both in political movements and in sociocultural mobilizations” (Martins, 2009, p. 1). We add that she was also present at CPII as a teacher and with her partnership with regular teacher José Rodrigues Leite Oiticica, which confirms Martins’ statement (2013, p. 30) that, “Though invisible in historiographic production for a long time, female anarchist activists in Brazil fought alongside men in defense of libertarian postulates”.

Born in the city of Oliveira, Minas Gerais, on July 22, 1882, he was the fourth of seven children of former constitution writer and senator Dr. Francisco de Paula Leite e Oiticica. Graduated in Law in 1902, he studied Medicine, but did not finish it36; he left these fields instead to dedicate himself to teaching and, being a combative anarchist, was arrested several times. He started in education at Paula Freitas School [Colégio Paula Freitas], RJ, teaching History. According to Lauris Jr., 2009, in 1906 he founded the Latin American School [Colégio Latino Americano], where he employed the pedagogical methods of the Frenchman Edmond Demulins, little known in Brazil. In 1916, he was admitted to CPII as a Portuguese teacher. As an applicant, he defended “[...] a thesis in which he showed the errors contained in the books of those who were going to examine him [...]”, says Edgar Rodrigues, in the presentation of José Oiticica’s ‘Anarchist Doctrine for All’ [Doutrina anarquista ao alcance de todos] (1983, p. 103). At CPII, he taught for 35 years, until retirement, maintaining his anarchist activism.

While teaching, he also worked at the Normal School [Escola Normal] and at the University School [Colégio Universitário] of the University of Brazil [Universidade do Brazil]. Maria de Lourdes also taught at the latter, between 1938 and 1942, hired as a supernumerary teacher, pursuant to Decree-Law No 882 of November 23, 1938, provided for in the public notice of the competitive examination published in Diário Oficial, on April 1 of that year (Diário de Notícias, 1938).

Because the sources that referred to Maria de Lourdes were scattered, we worked with the perspective of (re)building her life and professional journey through fragments of the past, by means of clues and signs found in her publications, which suggest a greater connection with the authors she read and who influenced her, as well as how she read these works. This type of analysis is based on Ginzburg’s life story composition (2006), which seeks possible relationships between the singular and the collective, attentive to the details and signs present in documents. This look gives the individual greater potential to act before the structures, which is different from the perspective in which the constitution of individuality is only possible when the roles that the individual plays are inserted in a universe that allows them to chart their way.

The sources suggested that she was part of the group of female anarchist activists in Brazil, standing out in the defense of women’s emancipation. On the occasion of The Leopoldina Railway Company’s strike, in 1920, Maria de Lourdes spoke at the rally in the garden of Praça da República, RJ, pointing to anarchism as the way to liberation.

In addition to participating in group organizations and public demonstrations, she signed articles in the libertarian press, such as A Obra, A Voz do Povo, and in the A Razão newspaper, although this one was not anarchist37. Moreover, between 1920 and 1922, she took part in the foundation of the Feminist League of Social Studies [Liga Feminista de Estudos Sociais]38, in the 1st Brazilian Feminist Conference, whose committee had Leoninda Daltro, and in the Brazilian Women Legion [Legião da Mulher Brasileira] (O combate, 1922).

According to Martins (2009, p. 1), Maria de Lourdes, along with other activists, made it a point “[...] to clarify that the revolution had not made nor would make women a public thing, and that the freedom they claimed for both sexes did not mean debauchery”.

Although it was not possible to specify whether Maria de Lourdes kept her fierce activism while working at CPII (1927-1949), she maintained her teaching partnership, throughout this period, with teacher José Oiticica. Anarchist studies make no reference to her after 1920, nor to her parents or schooling. The documents did not point in this direction either.

When we consulted the NUDOM/CPII collection and the press, there were, at first, doubts as to whether Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, an activist, and Maria de Lourdes Nogueira França, a writer, were the same person. This doubt was due to a difference in writing style in press columns and due to the surname. The doubt can be clarified by the teacher herself through a statement published in 1916, in Jornal do Comércio, in which she informed that, as of that publication, she would sign her name as Maria de Lourdes Ramos Nogueira, and no longer as Maria de Lourdes Nogueira França. Still, we found publications with this surname until 1920.

With the last name França, which she inherited from her husband Nogueira França, and from which she abdicated, we found news related to family events, such as the celebration of the engagement of her son Eurico Nogueira França39, born in 1913, and the commemoration of a mass for her one-year death anniversary, held on August 21, 1968 (Correio da Manhã, 1968).

It was also necessary to resort to the crossing of sources, which indicated, from some evidence, eliminations and connections, that Maria de Lourdes was born in the late nineteenth century, since her son was born in 1913. From a ‘death note’, published in Jornal do Brasil on February 28, 1947, about her father’s seventh-day mass, and from an article in Jornal Theatro e Sport congratulating her on her birthday, on May 9, 192540, it was possible to check her parentage: Francisca Ramos Nogueira, her mother, and Virgílio da Fonseca Nogueira, her father. In addition to the approximations regarding the date of her birthday, it was possible to establish relationships between the references found in the Fon Fon magazine, in which she published literary essays between 1914 and 1920, and in the A Razão and Voz do Povo newspapers, which published her libertarian speeches.

We brought some publications from the Fon Fon magazine, such as ‘Sonia’s Engagement’ [O noivado de Sonia], 1915, which has Russia as scenario; the text entitled ‘Ambition’ [Ambição], 1915, which tells the story of a woman who found true love and happiness when she let go of her material wealth; and the poem ‘Desire’ [Desejo], 1920, in which she speaks of her rising to the desire for freedom.

In ‘Sonia’s Engagement’ (Figure 1), the reader encounters a climate of political tension that preceded the Russian Revolution, and the denunciation of the tyranny of the then Czar Ramanoff, expressed soon at the beginning of the text, in the excerpt: “Russia. In the wave of convicts, who, for political crimes, went to the inhospitable regions of Siberia [...]” And yet: “Walked towards death. Oh, because they dared to plot against the power of Tsar Ramanoff” (Fon Fon, 1920a, p. 12). There is also mention of a ‘voluntary martyr’, whose father was looking for her, a characteristic that can also be attributed to the author, when analyzing her role in the Anarchist Movement in Brazil.

In her poem ‘Desire’ (Figure 2), more subjective aspects are expressed by the suffering of living in a world that the author deems ‘perverted and false’, and it is possible to establish from that a relationship with her other work entitled ‘Ambition’, in that happiness can only be achieved with a detachment from material goods. In said poem, this message is also present in the expressions: “You would give me the honors that are given to the saints” and “And, my Love, is... is...your bare foot.”

Libertarian matters arose in these publications, but her activism appeared in a subtle manner, unlike her writing in the press, during the period in which she played a major role in the Anarchist and Feminist Movements of Rio de Janeiro, namely: in the Feminist League of Social Studies, in the 1st Brazilian Feminist Conference, and in the Brazilian Women Legion, just as the study by Martins (2009, 2013) pointed out, identifying her as an ‘activist poet’.

In the Fon Fon magazine, on November 20, 1920, we found a picture of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira (Figure 3) in an advertisement announcing her works: ‘Literary Fragments, Essays’ [Fragmentos, ensaios literários] and ‘Love and Art’ [Amor e arte], published at the time.

In 1920, Maria de Lourdes inaugurated a Portuguese Philosophy course41, intended for CPII examinees, being introduced by the press as a teacher, poet, prose writer and niece of Luiz Pereira Barreto (Pelas Escolas, 1920).42

The doubts about the authorship of the writings could also be clarified by the close relationship of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira with teacher José Oiticica, as confirmed by the news article entitled ‘November Anarchist Agitation: The Results of Police Research’ [Agitação anarquista de novembro: os resultados das pesquisas policiais], published in 1919, in Revista Contemporânea, about the interrogation they both went through due to their involvement in the strike movement of November 18, 1918:43

In the investigation, this lady ‘Maria de Lourdes Nogueira’ was also heard, not contradicting the statements of teacher Oiticica, and those named as knowing best the role played by teacher Oiticica, Messrs. Carlos Dias, Ricardo Corrêa Perpetua and Manoel Campos, ‘all arrested, even though they did not want to say anything’ (Revista Contemporânea, 1919a, author’s emphasis).

According to information from the police investigation, José Rodrigues Leite Oiticica, a teacher at CPII, would have been accused of heading the movement considered to be subversive of the public order, along with Carlos Dias, Ricardo Corrêa and Manoel Campos, leading workers to the general strike, which took place on November 18, 1918 (Revista Contemporânea, 1919b) 44. Also according to the news published in O Jornal, of 1918, Maria de Lourdes was arrested to be interrogated together with teacher Oiticica, for anarchist actions (Lamounier, 2011).

Maria de Lourdes was active in the Anarchist Movement, engaging not only in strikes, but also in leagues, assemblies, demonstrations, conferences and the press. In 1919, she wrote a column for the A Razão newspaper, in which she transcribed excerpts and considerations about Urich Avila’s lecture. Preceding the transcription, Maria de Lourdes draws the reader’s attention: “It is never too much, however, to repeat that which makes our hearts vibrate, in the sincerity of our convictions, and I therefore transcribe this luminous passage [...]”, continuing with Urich Avila’s pronouncement: “We want: ‘A true society, says Urich. In which, with the abolishment of the artificial inequalities among individuals and, therefore, class differences, competition will be replaced by cooperation [...]’”. And she concluded with the expression: “Hail! Russia, cradle of the new era!”, probably referring to the revolution in the USSR that took place in 1917 (Era nova II, 1919, author’s emphasis).45

Faced with the police’s actions, which worked in the sense of repressing this movement, persecuting its representatives, just as what happened on the occasion of the 1918 strike, Maria de Lourdes wrote an article published in the journal A Obra, in August 1920, standing against this attitude, the excerpt of which was transcribed by Martins (2009, p. 2).

Ever since I joined the ranks of the combatants for the new social order, I implicitly took on the enormous responsibility of striving, relentlessly, for the advent of the new era, in which there is to be more justice and more harmony among men. The unshakable faith that encourages me is the same faith that makes the lips of our comrades set ajar in smiles, thrown into the back of the dungeons or ruthlessly banished to the inhospitable regions of Africa. What does it matter to them, however, if the bourgeois and capitalist blindness today calls them arsonists, bombers and quejandras? What do they care about the narrowness of a dungeon or the infected bilge of a ship, if the victory of the great ideal constitutes life’s reason for being? Let us not stop then!

According to Martins (2009), the Women’s Communist League [Liga Comunista Feminina], founded on May 27, 1919, did not last long because of the police persecution, and the Women’s Social Studies Group [Grupo Feminino de Estudos Sociais], of an educational nature, founded in RJ, on January 22, 1920, released ‘A Manifesto to Brazilian Women’ [Um manifesto à mulher brasileira], with the goal of fighting the issues that suffocated the ‘female sex’. The Group’s proposal was

[...] to unite all emancipated women in Brazil, in order to systematically and effectively fight the clerical enslavement, economic enslavement, moral enslavement and legal enslavement that suffocate, degrade and demean the female sex. As an alternative, the Group sought to provide women with an education capable of leading them to assimilate the reasons for social exploitation, demystifying the economic and sociocultural factors that put women in a condition of subordination. In this sense, the Group opposed the tendency of education to privilege techniques and arts considered inherent to the feminine nature, support for the so-called ‘women’s jobs’ (Martins, 2009, p. 2, author’s emphasis).

Maria de Lourdes Nogueira was the secretary at the first meeting of the Women’s Social Studies League [Liga Feminina de Estudos Sociais], also known as Women’s Social Studies Group, which was held in the headquarters, at Av. Passos, 106. This meeting addressed the installation of the Women’s Communist League, in 1919, the agreement bases of the latter were read, and the first year of the death anniversary of Rosa Luxemburg46 was commemorated, with a lecture by Álvaro Palmeira47. In the same year, it was Maria de Lourdes who gave a lecture on Rosa Luxemburg. An assembly of the Women’s Social Studies Group or League, chaired by her, was held at the Graphic Association [Associação Gráfica], with the lecturer Barbosa, who spoke on social issues and matters of interest to women. At the end, the stanzas of The Internationale were chanted (A Razão, 1920a; Voz do Povo, 1920).

In the press, she appeared calling on women to take part in the Group. She also spoke at a rally encouraging women to join the Study Group, held in the garden of Praça da República, Federal District, on the occasion of The Leopoldina Railway Company’s strike, in 1920. The rally was opened by Elisa Gonçalves48, who spoke about violence against working families. Afterwards, Maria de Lourdes spoke about women and working women. In support of the strike, she delivered the following speech:

[...] I urge you! Group yourselves! With us! Join our women’s study group, so that you can teach, transmit to your children and to the people who live with you, the great and holy ideals of human progress! [...] The times have arrived and, with them, the victory of Good, eliminating economic inequality, social contrasts, wars, prostitution, indigence and the miserable exploitation of man by man [...]. (Voz do Povo, 1920)49

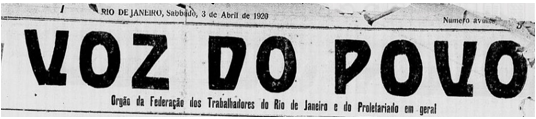

Still in 1920, some changes were signaled both concerning the objectives and the leaders of the Feminist Movement of Rio de Janeiro. For instance, the change in the layout of the issue of April 3, 1920, of the Voz do Povo newspaper (Figure 4), which used to be smaller and had fewer pages, resembling a pamphlet, and started to identify itself, right on the first page, as a ‘Body of the Workers’ Federation of Rio de Janeiro and of the General Proletariat’, written below the title.

This change indicated a closer relationship between anarchists and the labor movement. It was also found that Maria de Lourdes’s publications no longer appeared in the newspaper. There are only references to her in the Correio column of Voz do Povo, in which notices about letters and printed matter addressed to members were posted. This suggests that, although she did not distance herself from the Movement, her protagonism among the leaders diminished, to a certain extent.

Another indication of this change was the formal sitting held by the board of the Brazilian Women Legion50, at the Commerce Association [Associação do Comércio]. The event was announced in the Diário de Manhã and A Razão newspapers, on May 17, 1920. The president, Olga Doyle, was present at the table that led the work, as well as: Cecília Meireles, Laurinda Santos Lobo, Margarida Lopes de Almeida, Luzia Serrano, Aurea Pires da Gama, and the speaker Pinto da Rocha, who addressed the ‘the Family and the Nation’ theme. The event also counted on a speech by Cecília Meireles, then secretary, about helpless mothers. It is worth noting that the name of Maria de Lourdes appears on the attendance list, without any highlight (A Razão, 1920b; A legião da mulher brasileira, 1920).

Her name also appeared in the organizing committee of the 1st Brazilian Feminist Conference, which was scheduled to take place between April 1 and April 15, 1921. In addition to her, the following were mentioned: Leolinda Daltro (teacher), Viscondessa de Saade, Mrs. Serzedello Correia, Adelina Savart de Saint Brisson (writer), Maria L. Fagundes Varella e Silva (teacher), Dr. Ermelinda Lopes de Vasconcellos (doctor), Aurea C. Daltro (teacher), Luiza de Souza Dias (teacher), Gilka da Costa Machado (writer), Alice A. Pimenta (writer), Conceição de Andrade (journalist), Mrs. Augusta Kauffman da Silva (A Noite, 1921), providing evidence of her networks of sociability.51

According to Fraccaro (2018, p. 17, author’s emphasis), in the 1920s, initiatives for the creation of women’s groups that specifically addressed the matter of working women52 stood out in the anarchist organization. However, both the International Women’s Federation [Federação Internacional Feminina], which acted in 1922, and the Women’s Center [Centro Feminino], in 1924,

[...] gave lectures that addressed conformism before the harsh social reality, and the importance of rebellion for the group that was organized around neighborhood leagues and the A Plebe newspaper. They considered teacher Leolinda Daltro and her electoral intentions as ‘politicking sentiments of the old constitutional feminist’.

Perhaps because of these contradictions within the feminist movement53, Maria de Lourdes Nogueira distanced herself or changed her focus, taking actions more linked to the educational field. In an advertisement posted in the press about the work Organum, by the Lafayette Institute [Instituto Lafayette]54, she was mentioned in the summary on Art as the author and translator of Horacio, from Latin to Portuguese (Organum, 1922).

In 1924, Jornal das Moças commented on her work entitled ‘Need for Constructions Intended to Preserve Unborn Children’ [Necessidade de criação de obras destinadas à preservação de nascituros], which proposed a new building or the expansion of the Institute for Childhood Protection and Assistance [Instituto de Proteção e Assistência à Infância] to the department for the preservation of unborn children, in order admit mothers three months before delivery; it acclaimed Dr. Moncorvo Filho as director of the institution, who would be in charge of organizing clinical and surgical services, as well as special clinics; it proposed the organization of a cooperative to maintain expenses, and the creation of child hygiene and sewing courses for mothers to learn how to make layettes (Necessidade de criação de obras..., 1924).

In addition to her publications, she would have dedicated herself to studies, graduating in Languages from Santa Úrsula University [Universidade Santa Úrsula], a Catholic institution founded in 1939, in RJ (Formaturas, 1943). There are also indications that she would have started the Law course at the University of Rio de Janeiro [Universidade do Rio de Janeiro], around 1938, but it was not possible to check if she finished her studies. Between 1938 and 1942, she also taught at the University School (Diário de Notícias, 1938).

Her work teaching at Pedro II School

In 1927, Maria de Lourdes Nogueira was admitted as a supplementary Portuguese teacher at the Day school of Pedro II School, as stated in the CPII Report by principal Euclides Roxo (1927-1929), and as an occasional examiner for Portuguese exams (Roxo, 1928).

Although it was not possible to evidence whether there was any degree of kinship between her and teacher Julio Nogueira, also from CPII, it is known that this teacher was appointed as interim French teacher at the Boarding school and named to be temporarily in charge of the chair of English at CPII, in 1927, after having worked as a teacher ‘above regular teachers’ for the supplementary classes of the Day school, between 1925 and 1926. In 1931, he was also the teaching-head teacher, when the position of French, English and German teacher was extinguished at CPII. Later, he appeared in the Portuguese Program, in 1947, a subject taught by Maria de Lourdes throughout the period in which her presence at CPII was found (1927 to 1949). During this period, teacher Oiticica (1916 - 1951), who took the chair of Portuguese, also worked at the institution (Escragnolle Doria, 1939; Soares, 2014).

As each regular teacher took on up to four supplementary classes55, we can infer that these teachers were the ones who chose who would help them teach these classes. It was not possible, however, to specify whether she stayed at the institution after teacher Oiticica left. We can note that among the teachers, Clara Oiticica had the same surname as the teacher in charge of the Portuguese chair, José Oiticica, in 1920, who was also editor of the Voz do Povo newspaper, along with Maria de Lourdes. On the occasion of the 1918 strike, both were interrogated. Being a regular teacher at CPII, the position allowed him to have a certain influence on the admission of these women to the teaching staff, since they were part of his social circle.

The partnership between José Oiticica and Maria de Lourdes continued at CPII and was expressed in the news about the constitution of the Examining Committees for the exams of the Portuguese subject, in the elementary course of this educational establishment, in which both participated. In 1941, she composed the committee together with teachers Oiticica, Francisco Gonçalves and Silvio Eliz, and, in 1942, she was in a commission made up of the same teachers, in addition to Curio de Carvalho (Pelas escolas, 1942).

In 1939, Maria de Lourdes was ranked second for the position of supplementary Portuguese teacher at CPII (Colégio Pedro II, 1939). In 1942, she became a supernumerary teacher56, paid monthly, at CPII, with a position of 12 hours a week and salary of 1:600$0. Her role as a teacher and writer did not end there. In the same year, she had her contract renewed to teach at the University School and published an article entitled ‘Santa Úrsula Institute’ [Instituto Santa Úrsula], in the journal Formação: Revista de Educação (Nogueira, 1942). The 1942 edition of the journal addressed the reform of Secondary Education.

She also continued with her private lessons in the preparatory course for CPII’s exams, now teaching Latin and Portuguese for competitive examinations together with teacher Joaquim Inácio (Contratados, 1942).

Despite all her literary journey, her higher education degree came late. After she graduated in Languages, in 1943, it was not possible to specify whether she continued working at the University School of the University of Brazil, only at CPII, where we found references about this teacher until 1949. She passed away in 1967.

We noticed that, in some moments of her journey, she did not use her husband’s last name, and there was sparse information about her private life in the press. Although her son, Eurico Nogueira França (1913-1992), was recognized by the Brazilian Music Academy [Academia de Música Brasileira], having his biography published, it does not contain information about his parentage. Neither does Vasco Mariz, Eurico’s friend, in the text ‘Remembering Eurico Nogueira França (1913-1992)’ [Recordar Eurico Nogueira França (1913-1992)] mention his parents’ name; however, he mentions them when speaking of the formation journey of our protagonist’s son, teacher Maria de Lourdes Nogueira.

[...] although he was attracted by music from an early age, perhaps due to the influence of his parents, he studied and graduated in Medicine from the former University of Brazil, in 1934. He did not abandon his passion for music and ended up graduating in Piano from the National Music Institute [Instituto Nacional de Música], now the UFRJ’s Music School, at Rua do Passeio (Mariz, 2012, p. 376).

Further considerations

Throughout the process of defining and analyzing Maria de Lourdes Nogueira’s course, some obstacles were encountered. Although the sources found are diverse, it was possible to notice an erasure of the role of this teacher in the Anarchist Movement, during the period in which she worked at CPII.

The press, in particular, was key to help us compare data that, at first sight, seemed contradictory. As for the gaps, they are still subject for further research, and so are the questions about the reasons that led her to join the feminist movements of the time, which distanced themselves from the anarchist perspective.

In addition to diving deeper into her journey in these movements, it is also worth looking for other sources that bring evidence of her training process and initial schooling, about which we found no traces. One possibility that emerges is to seek sources that refer to other educational institutions where she worked.

Despite the gaps, this analysis advanced in relation to the studies produced so far on anarchist women, contributing to breaking with the silence on the course of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira, after the 1920s, and on her activity as a teacher in secondary education at CPII and at the University School, between 1927 and 1949.

The surveys, as well as the debates about her literary production, show that, as a ‘cultural mediator’, she reached much wider public spaces than publications in the anarchist press did, also encompassing the educational field. So much so that several newspapers and journals made reference to her, indicating her fields and possibilities of action and a diverse network of sociability, reaffirming her protagonism in the history of the Anarchist Movement in Brazil, which indicates contributions to the history of women, especially anarchist ones, and to the History of Education.

Gender as a category of analysis helped us think about how she performed, whether in the movements, in the press or in educational institutions, showing the power relations that exist in these spaces of sociability, which indicated hierarchies between regular, assistant and supplementary teachers in the teaching staff of CPII, with the first position not being accessible to women. However, these power relations were not limited to the hierarchy between men and women, as the positions of assistant and substitute teachers were filled by both sexes.

The perspective approached in this article allowed giving prominence to Maria de Lourdes, removing her from a secondary role and showing that she also had a major participation in the Anarchist Movement, contributing to the studies on this theme in Brazil and Latin America.

REFERENCES

Alves, R. L. (2009). Trajetórias femininas no Colégio Pedro II. In Anais do 25º Simpósio Nacional de História (p. 1-10). Fortaleza, CE. [ Links ]

Andrade, V. L. Q. (2016). Colégio Pedro II: patrimônio e lugar de memória da educação brasileira. In A. M. Gasparello & H. O. S. Villela (Eds.), Educação na história: intelectuais, saberes e ações instituintes (p.101-116). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Mauad X. [ Links ]

Colégio Pedro II. (1939). Diário de Notícias. [ Links ]

O Combate. (1922, 23 de outubro). n. 2217, p. 3. [ Links ]

Congresso Feminista Brasileiro. (1921). O Combate. [ Links ]

Contratados. (1942). A Manhã. [ Links ]

Correio da Manhã. (1968, 20 de agosto). c.1, p. 10. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 510, de 22 de junho de 1890. (1890). Publica a constituição dos Estados Unidos do Brazil. Publicação original [Coleção de Leis do Brasil de 31/12/1890 - vol. 006] (p. 1365, col. 1). Recuperado de: http://senado.gov.br. [ Links ]

Diário de Notícias. (1938, 29 de dezembro). s. 1, p. 6. [ Links ]

Diário de Notícias. (1938, 16 de maio). [ Links ]

Dubar, C. (2012). A construção de si pela atividade de trabalho: a socialização profissional. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 42(146), 351-367. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. (2002). Le Declin de l’Institution. Paris, FR: Éditions du Seuil. [ Links ]

Dubet, F. (2011). Mutações cruzadas: a cidadania e a escola. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 16(47), 289-305. [ Links ]

Era nova II. (1919, 21 de abril). A Razão. [ Links ]

Escragnolle Doria, L. G. (1939). Commemorativa do 1º Centenário do Collegio de Pedro Segundo (2 de dezembro de 1837 - 2 de dezembro de 1937). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

Fon Fon. (1915). n. 18. [ Links ]

Fon Fon. (1920a). n. 4 e 12. [ Links ]

Fon Fon. (1920b). ano XIV, n. 47. [ Links ]

Formaturas. (1943). Diário Carioca. [ Links ]

Fraccaro, G. C. C. (2018). Uma história social do feminismo: diálogos de um campo político brasileiro (1917-1937). Estudos Históricos, 31(63), 7-26. [ Links ]

Gazeta de Notícias. (1945, 6 de julho). c. 2, p. 6. [ Links ]

Ginzburg, C. (2006). O queijo e os vermes: o cotidiano e as ideias de um moleiro perseguido pela Inquisição. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Gomes, A. C., & Hansen, P. S. (2016). Intelectuais mediadores: práticas culturais e ação política. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Civilização Brasileira. [ Links ]

Gonçalves, A. L. (2006). História & gênero. Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Grupo Feminino de Estudos Sociais. (1920, 19 de março). Voz do Povo, n. 42, p. 2. [ Links ]

Guimarães, L. A. P. (2014). A educação do trabalhador no movimento operário da Primeira República no Rio de Janeiro: apropriações e traduções do pensamento de Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (Tese de Doutorado). Departamento de Educação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Jornal de Theatro e Sport. (1925, 09 de maio). [ Links ]

Jornal do Brasil. (1925, 22 de dezembro). [ Links ]

Jornal do Brasil. (1940, 29 de fevereiro). [ Links ]

Lamounier, A. A. (2011). José Oiticica: itinerários de um militante anarquista (1912-1919) (Dissertação de Mestrado). Programa de Pós-graduação em História Social, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina. [ Links ]

Lauris Jr., R. L. (2009). José Oiticica: reflexões e vivências de um anarquista (Dissertação de Mestrado). Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Estadual Paulista, Campinas. [ Links ]

A Legião da mulher brasileira. (1920). Diário da Manhã. [ Links ]

Louro, G. L. (2007). Mulheres na sala de aula. In História das mulheres no Brasil (p. 441-481). São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Marinho, N. (2016). A engenheira militante feminista Carmen Portinho: a atuação na União Universitária Feminina. In A. M. Gasparello & H. O. S. Villela (Eds.), Educação na história: intelectuais, saberes e ações instituintes (p. 215-232). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Mauad X. [ Links ]

Mariz, V. (2012). Recordar Eurico Nogueira França (1913-1992). Revista Brasileira de Música, 25(2), 375-380. [ Links ]

Martins, A. M. R. (2009). A invisibilidade de Maria de Lourdes Nogueira: mulher, militante, libertária. Emecê. Boletim do Núcleo de Pesquisa Marques da Costa, 4(12), 1-2. [ Links ]

Martins, A. M. R. (2013). Mulher liberta-te!: o anarquismo e as mulheres. In J. Lima, A. Roberti & E. Santos (Eds.), Pensando a história: reflexões sobre as possibilidades de se escrever a História através de perspectivas interdisciplinares (p.25-48), Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Mendonça, A. P. C., Soares, J. C., & Lopes, I. G. (2013). A criação do Colégio de Pedro II e seu impacto na constituição do magistério público secundário no Brasil. In Anais do 7º Congresso Brasileiro de História da Educação (p. 985-1000). Cuiabá, MT. [ Links ]

Mendonça, A. W. P. C. (2015). O Colégio Pedro II e seu impacto na constituição do Magistério Público Secundário no Brasil (1837-1945). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 15, 167-171. [ Links ]

Nogueira, M. L. (1942). Instituto Santa Úrsula. Formação: Revista de Educação, 46. [ Links ]

A Noite. (1921, 31 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Oiticica, J. (1983). A doutrina anarquista ao alcance de todos. São Paulo, SP: Econômica. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P., & Costa, N. M. (2020). As mulheres no Ensino Secundário: percursos das primeiras professoras do Colégio Pedro II. História em Reflexão, 14(27), 321-344. [ Links ]

Oliveira, P. R., & Costa, N. M. (2019). O percurso da professora Maria da Glória Ribeiro Moss no Colégio Pedro II: “o famoso concurso de química” (1926-1939). Revista HISTED-BR, 19, 1-21. [ Links ]

Organum. (1922). Jornal do Brasil. [ Links ]

Pelas escolas. (1920). A Noite. [ Links ]

Pelas escolas. (1942). Jornal do Comércio. [ Links ]

Perrot, M. (2012). Minha história das mulheres. São Paulo, SP: Contexto. [ Links ]

Necessidade de criação de obras destinadas à preservação de nascituros. (1924). Jornal das Moças. [ Links ]

Rago, M. (2012). Entre o anarquismo e o feminismo: Maria Lacerda de Moura e Luce Fabbri. Verve, 21, 54-78. [ Links ]

A Razão. (1920a, 22 de janeiro). p. 8. [ Links ]

A Razão. (1920b. 17 de maio). [ Links ]

Revista Contemporânea. (1919a, 02 de janeiro). [ Links ]

Revista Contemporânea. (1919b, 18 de novembro). p. 20. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, E. (1993). Libertários: José Oiticica, Maria Lacerda de Moura, Neno Vasco Fabio Luz. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: VJR Editores Associados. [ Links ]

Roxo, E. M. G. (1928). Relatório concernente aos anos letivos de 1925 e 1926. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Colégio Pedro II. [ Links ]

Saffioti, H. I. B. (2013). Rearticulando gênero e classe social. In C. Bruschini & A. O. Costa. Uma questão de gênero (p. 188-215). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Rosa dos Tempos. [ Links ]

Santos, B. B. M. (2013). O Núcleo de Documentação e Memória do Colégio Pedro II e sua importância para a preservação do patrimônio histórico e cultural da educação brasileira. In N. M. Costa & L. Xavier (Eds.), A história da educação no Rio de Janeiro: identidades locais, memória e patrimônio (p.36-44). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Letra Capital. [ Links ]

Schumaher, S., & Brazil, É. V. (Org.). (2000). Dicionário mulheres do Brasil: de 1500 até a atualidade biográfico e ilustrado. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Jorge Zahar Ed. [ Links ]

Silva, F. B. (2013). Luís Pereira Barreto: uma abordagem positivista da moralidade e da realidade brasileira. Revista Estudos Filosóficos, 11, 16-23. [ Links ]

Silva, M. G. (2019). Álvaro Palmeira: de comunista a legalista, de legalista a revolucionário. Revista Contemporânea de Educação, 14(30), 67-87. [ Links ]

Soares, J. C. (2014). Dos professores estranhos aos catedráticos: aspectos da construção da identidade profissional docente no CPII (1925-1945) (Tese de Doutorado). Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Humanas e Educação da PUC-Rio), Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Soares, J. C., & Silva, G. M. (2018). Dentre a reforma Rocha Vaz e o Estado Novo: os professores suplementares do Colégio Pedro II. RBHE, 22(56), 146-164. [ Links ]

Voz do Povo. (1920, 03 de abril). [ Links ]

Xavier, L. N. (2014). A construção social e história da profissão docente. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 19(59), 827-849. [ Links ]

29 The ‘men of the world’, according to Mendonça, Soares and Lopes (2013) and Mendonça (2015), occupied the chairs of CPII and did not have teaching as their main profession, seeing the prestige of this institution only as a steppingstone for them to rise to better positions.

30Nella Aita participated in the competitive examination for regular teacher at CPII, chair of Italian, in 1921. Though approved, she did not qualify. The same happened with Maria da Glória Ribeiro Moss, in the competitive examinations of 1933 and 1939. She, however, worked at CPII, in 1926, as an assistant Chemistry teacher (Oliveira & Costa, 2019).

31The study of these teachers was developed by Oliveira and Costa (2020).

32Studies on the Feminist Federation led by Bertha Lutz identify it as composed of elite women with liberal conceptions, who fought for the right to universal suffrage, unlike the Anarchist Movement in which Maria de Lourdes participated, which was linked to the labor movement. According to Rago (2012), for anarchists, liberal feminism was very conservative, as it did not question the structures of bourgeois society and did not address the issue of sexual morality and violence in gender relations. About the act of voting, José Oiticica spread these words: “Voting, for a worker, is a crime, and against mandatory voting they must come up with an effective protest, practicing the voting strike” (Oiticica, 1983, p. 22).

33 Santos (2013) explains that regular teachers designed the teaching programs. Thus, they were responsible for the content of the chairs (subjects), in addition to taking part in the main political and pedagogical decisions. “Being mostly authors of textbooks adopted by the School, they were likened to professors, with many of them working at both levels of education.” These teachers “[...] formed a category of author teachers, intellectuals from the academies, who were in charge of higher and secondary education, thus contributing to the educational project of the Nation State” (Santos, 2013, p. 38).

34According to Dec. 510 of 1890, art. 62, education was lay and free in all grades, and free of charge in primary school. CPII maintained at the beginning of the Republic, as well as in the Empire, an elitist character reserved for male students.

35Piotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (1842 - 1921) was a Russian anarchist geographer, considered as the founder of the anarcho-communist current or libertarian communism in the late 19th century. In his view, everyone is equal and, for this reason, must “[...] work in accordance with their possibilities and receive the results of their work in accordance with their needs”. For him, with the expansion of freedom, “[...] man has his existence guaranteed and is not forced to sell his strength and intelligence to those who want to do him the charity of exploiting him” (Kropotkin apud Guimarães, 2014, p. 145).

36He published in the labor and anarchist presses and in the mainstream press, such as the Correio da Manhã newspaper, as a collaborator from 1918, and as a columnist from 1921 to 1927 (Lauris Jr., 2009).

37These newspapers in which Maria de Lourdes published are important because they give us clues about her relationship with Oiticica, before working at the CPII.

38In a news article published by the Voz do Povo newspaper, Maria de Lourdes refers to the League as Women’s Social Studies Group (1920). She calls out: “[...] Oh! Brazilian and foreign women! All come and work with us. Bringing us the contribution of your energy and of your intelligence! Then, it will not be said in Brazil that women live indifferent to the serious and transcending problems of social harmony”. Another denomination found in the same newspaper to refer to the League is ‘Women’s Social Studies Center’.

39The news published in 1945 about the engagement of Eurico Nogueira França indicates that Maria de Lourdes Nogueira França, his mother, was married to Nogueira França. Eurico, a physician and music critic for Correio da Manhã, became engaged to Ivy Improta, daughter of Carlos Nelson Improta and Anselmina Improta (Gazeta de Notícias, 1945).

41In 1925, the announcement of the preparatory course in Portuguese and Latin for CPII taught by teacher Maria de Lourdes informs Rua do Carmo, 71, 2nd floor, as address. In 1940, it appears at another address: Rua Nilo Peçanha, 38-D, room 114 (Jornal do Brasil, 1925, 1940).

42Luís Pereira Barreto (1840-1923) was a physician, researcher and writer. Silva (2013) presents a discussion on the positivist morality proposed by Barreto.

43The Fon Fon magazine, issue 32 of 1941, brings the news article ‘The Poster of the Week’ [O cartaz da semana], about a dinner in honor of Manoel Lousada, in which teachers José Oiticica and Maria de Lourdes Nogueira would have participated as guests, among others who worked with the honored one at the University School of the University of Brazil.

44José Oiticica was arrested and deported numerous times. In 1918, he was arrested, accused of being ‘the commander’ of the insurrectionary General Strike, by the Chief of Police Aurelino Leal, being deported and confined in the State of Alagoas, with the agreement of Wenceslau Brás (Rodrigues, 1993).

45According to Martins (2013), Anarchism was present in the late 19th and early 20th century in Brazil, being constantly reinforced with the growing presence of immigrants, many linked to the commercial sector and workshops, projecting itself in different ways. However, they had as points of convergence: libertarian ideas and the denial of authority.

46A Polish leftist activist, Rosa Luxemburg (1871-1919) was a prominent member of Germany’s Social Democratic Party - SDP (Gonçalves, 2006).

47A normal-school graduate, a doctor and a principal, the anarchist Álvaro Palmeira worked as editor of the Voz do Povo newspaper, actively participating in the Anarchist Insurrection, in 1918. He passed away in 1992, at the age of 103 (Silva, 2019).

48Elisa Gonçalves de Oliveira founded, together with Elvira Boni de Lacerda and other women, in 1919, the Union of Seamstresses, Hatters and Attached Classes (Schumaher & Brazil, 2000).

49Leoninda Daltro turned to the issue of indigenous people, of the right to vote, and to the Anarchist Movement.

50With a feminism close to that of Bertha Lutz, the Brazilian Women Legion was created in 1919 by novelist Julia Lopes de Almeida and other women. According to the news, at the event in which the board took office, there were women other than workers, associated, for instance, with the Union of Seamstresses, Hatters and Attached Classes, and with the anarchist conceptions of Maria de Lourdes Nogueira.

51The 1st Brazilian Feminist Conference, held by the Women’s Republican Party, had an assembly scheduled for January 22, 1921. The news preached the preparation of Brazilian women for the aggrandizement of the Nation, on the occasion of the centenary of the Independence (Congresso Feminista Brasileiro, 1921).

52At the initiative of Maria Lacerda de Moura, who participated in the foundation of the League for the Intellectual Emancipation of Women.

53According to Rago (2012, p. 73), anarchism and feminism, by distancing their objectives and forms of struggle, configured distinct movements. However, the contribution of anarchists was enormous. In her words to Maria Lacerda de Moura, “[...] the fight against power and the struggle for the construction of anarchism are waged more strongly in the field of sexual morality and feminism”.

54Organum was published by the Lafayette Institute, an education institution in Rio de Janeiro. A Obra was composed of teaching contents in Mathematics, Astronomy, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Sociology, and Commerce, Industry and Agriculture.

55According to Soares (2014, p. 156), the supplementary classes in the New State were handled by the regular teacher of the subject, up to a limit of 12 classes per week, as long as authorized by the Minister of Education and Health. The supplementary classes not assigned to regular teachers would be the responsibility of assistant teachers, “[...] who would be admitted as hired supernumerary teachers, pursuant to the law in force. Assistant teachers were chosen among free teachers of the subject”.

56According to Soares (2014), in the context of the New State, the documents use the terms ‘supplementary teachers’ and ‘supernumerary teachers’ for the same category.

Received: June 03, 2020; Accepted: January 08, 2021; Published: July 02, 2021

texto en

texto en