Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.22 Maringá 2022 Epub 13-Dic-2021

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v22.2022.e197

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

In the course of teaching: itineraries of public male and female teachers in Antônio Prado, Rio Grande do Sul (1885 - 1920)

1Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, RS, Brasil.

The aim is to analyze the itineraries teachers in public classes in Antônio Prado - RS between the years of 1885 and 1920, thinking about traces of relationships and sociability, length of stay in their function, and teachers’ responsibility. The methodology used was historic document analysis, based on Education History and Cultural History in a micro-history. Antônio Prado - RS was a colony occupied from 1886, later district of Vacaria - RS, to 1899. Since its emancipation, it was managed by the administration of Innocencio de Mattos Miller. From the investigation, attention is drawn to the number of teachers coming from other locations, impermanence in the length of stay, absence of initial training and various actions that they performed at the same time, while teaching.

Keywords: history of education; primary education teachers itineraries; public school; rural school

O objetivo é analisar os itinerários de professores das aulas públicas de Antônio Prado - RS entre os anos de 1885 a 1920, pensando rastros de relações e sociabilidade, tempos de permanência na função e atribuições dos docentes. A análise documental histórica foi a metodologia empregada embasada na História da Educação e História Cultural, num viés da micro-história. Antônio Prado - RS foi uma colônia ocupada a partir de 1886, depois distrito de Vacaria - RS até 1899 e com a emancipação, o local foi gerido pela administração de Innocencio de Mattos Miller. Da investigação, chama a atenção a quantidade de professores, vindos de outras localidades, impermanências no tempo de atuação, ausência de formação inicial e diversas funções que exerciam concomitante com a docência.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; itinerários de professores do ensino primário; escola pública; escola rural

El objetivo es analizarlos itinerarios de los maestros de las clases públicas de Antônio Prado - RS entre los años 1885 y 1920, pensando los rastros de relaciones y sociabilidad, tiempos de permanencia en la función y atribuciones de los docentes. El análisis documental histórico fue la metodología empleada con base en la Historia de la Educación y en la Historia Cultural, en un sesgo de microhistoria. Antônio Prado - RS fue una colonia ocupada a partir de 1886, después distrito de Vacaria - RS hasta 1899 y con la emancipación, el lugar fue dirigido por la administración de Innocencio de Mattos Miller. De la investigación, llama la atención la cantidad de maestros provenientes de otras localidades, casos de no permanencia en el tiempo de actuación, ausencia de formación inicial y diversas funciones que ejercían concomitantemente a la docencia.

Palabras clave: historia de la educación; itinerarios de maestros de enseñanza primaria; escuela pública; escuela rural

Introduction

Throughout 1885, the first movements for the emergence of the Antônio Prado colony took place, in the Gaucho Highlands, Rio Grande do Sul (RS). After four years, two classes37 would be held in the immigrants’ shed, in the seat of said colony, with teacher Sérgio I. de Oliveira’s having 47 students and being taught in Portuguese for boys (Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami [AHMJSA], 1890b). The teacher was later appointed, and this class was the first indication of a public school in the area.

The colonization policy between the end of the Empire and the beginning of the Republic, in a Gaucho context, it is where the research proposal of this article is inserted, which sought to map the constitution of teaching in the schooling processes that were instituted in the colony and, later, municipality of Antônio Prado, in Rio Grande do Sul, especially for teachers38 working with public classes. Understanding who they were, how they became teachers, for how long they held their position, and whether they took on other roles besides teaching are points that mobilized us. Traces of the relationships and sociability of the subjects who dedicated themselves to the teaching activity, in order to participate in the history of education in Antônio Prado, RS, were investigated. Thus, the objective was to analyze the itineraries of public school teachers in Antônio Prado, RS, in their multiple relationships: training, appointment, practice, roles and networks of sociability in the time frame of 1885, beginning of the colony, until 1920, when the Marist School39 was installed.

The documents that compose the empirical research are made up of correspondences and reports from Antônio Prado’s intendance, filed in the Municipal Historical Archive of Antônio Prado [Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado] (AHMAP), and official letters issued by the Lands and Lot-Measurement Commission of the former Caxias colony, filed in the João Spadari Adami Municipal Historical Archive [Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami] (AHMJSA), as well as newspapers available on the National Library’s Digital Newspaper Archives. The historian of education occupation involves the “[...] ordering and rationalization of what has been lived, history is born as this handcrafted, patient, day-to-day, solitary, endless work done on the remains, the traces, on the monuments passed on to us [...] they ask for deciphering, they ask for comprehension and meaning” (Albuquerque, 2019, p. 30). They are scattered traces, nuances of existence of teachers, of their presence in classes under different conditions that we seek to map and of which we attempt to make sense.

Looking at the subjects requires a different level of interpretation, looking at them with a magnifying glass. We do so from the perspective of micro-history thought of as “[...] a practice and, in particular, a bet, a discussion: it is an attempt to work by changing the reality-reading scale [...]”, as stated by Levi (2017, p. 166), because in addition to naming or listing teachers working from 1885 to 1920, the details are investigated for us to understand not who they were individually, but the aspects and points of contact of their life itineraries. When looking with a magnifying glass or microscope, we realize that “[...] if reality is opaque, there are privileged zones - signs, clues - that allow us to decipher it” (Ginzburg, 2003, p. 177). From the various documents, we scrutinized the signs, the clues to compose the analysis and narrative that we present below.

The article is organized in two moments: in the first, we contextualize the researched location - Antônio Prado - and its displacement from a colonial center to its constitution as a municipality; in the second, we present the itineraries of teachers who worked, in particular, in public classes. At the end, we provide some considerations, as conclusion.

From colonial center to municipality, a brief contextualization

The year 1885 was passing, and the colonization of the Italian Colonial Region [Região Colonial Italiana] (RCI) received a high migratory inflow, evidencing a demand for new lands. Antônio Prado’s territory then belonged to Vacaria, Rio Grande do Sul (Barbosa, 1980) and became a colonial center. As for the name, it was justified with praise, on the grounds that “[...] the new center was named ‘Antonio Prado’40 as a deserved tribute to the services provided to the colonization of the province by the honored statesman who is currently in charge of agriculture, commerce and public roads” (Relatorio da Inspetoria..., 1887, p. 23, author’s emphasis).

The same report presented the result of the work conducted by the Land Commission, which, between 1885 and 1886, had measured 391 lots, opened local paths and trails, and settled around 400 immigrants. Immigrants’ workforce was employed to open roads, and they lived off the payment in the early times, while building their houses and working on the first crops. The report informed that “[...] along the lines of the lots, 13 wooden huts were built, where immigrants live until they have completed the construction of their temporary homes” (Relatório da Inspetoria..., 1887, p. 24). It also stated that “[...] it was imperative to found a new center endowed with the necessary elements for the well-being and prosperity of the immigrants who settled there, who no longer find easy placement in the old territories that are almost entirely occupied” (Relatório da Inspetoria..., 1887, p. 23).

The occupation of the Antônio Prado colony, in the Gaucho Highlands, took place with successive waves of newly arrived immigrants, mostly from the Italian peninsula, who were settled in plots measured and distributed by the Land Commission. In 1890, it was possible to see an increase in the records produced by the Land and Lot Commission of Antônio Prado concerning the settlement of immigrants; in these movements, the first indications of a male and a female teacher who worked in that place, still in the immigrants’ shed, appear. Thus, the colony emerged simultaneously with the first forms of schooling and teaching practice.

The growth of the colonial center and the occupation of the lots resulted, on February 11, 1899, in the administrative autonomy of the locality, which was emancipated from the municipality of Vacaria. From then onwards, the bases of the local political-administrative system were established, and intendant41 Innocencio de Mattos Miller took over the administration (Biavaschi, 2011). The first decades of the municipality were marked by the presence of republicans, and Innocencio42 managed Antônio Prado for 24 years, resigning only between 1907 and 1910, in favor of his deputy Cristiano Ziegler (Barbosa, 1980).

In the mid-twentieth century, the small town was characterized by the presence of immigrants and descendants of Italians43, Catholics and, mostly, farmers settled in rural areas. The population had an average of 10,000 inhabitants (A Federação, 1909). Over the years, improvements were made in both access roads and routes for the distribution of agricultural production to the capital, one of the most recurrent demands of the residents.

In 1911, the Union and Mutual-Aid Club, an agricultural cooperative, was founded. At the end of 1912, Giuseppe Antoniuti created a family cinema. In 1915, a telephone line began connecting neighboring districts and municipalities (Bernardi, 2020). A year later, the newspaper O Pradense was created. The predominance of agricultural activities and sawmills multiplied (Barbosa, 1980). The emergence of five bank branches and ten hotels in the seat is worth highlighting, with the latter having, in 1914, a flow of 1,139 people (Barbosa, 1980).

Thus, it is possible to observe changes, but a detailed analysis shows that, for instance, even at the height of the cooperative, after 1914, cooperativism was underdeveloped in the municipality (Antônio Prado: como ele..., 1972), which marked the period with some stagnation. The possibility of re-emigrating to the northwest of Rio Grande do Sul, as well as new private colonies in the west of Santa Catarina and Paraná, became an attractive option for many families. The exodus, between 1900 and 1915, accounted for approximately 30% of the population (Bernardi & Luchese, 2020). The intendant refers to the period as an “[...] appalling crisis whose malign effects extend far and wide” (Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado [AHMAP], 1915, p. 3). Throughout the 1920s, albeit slowly, the municipality resumed its growth.44

The seat of the municipality, though relatively small, had a greater flow of people and services, with a predominance of administrative, commercial and financial activities. The hinterland, with the exception of the headquarters of the chapels45, would be characterized by multi-crop smallholders and family labor force.

Itineraries of public teachers in Antônio Prado

The seat immigrants’ shed was completed in December 1886 (Bertaso & Lima, 1950). It is known that, for at least a decade, it sheltered immigrants who, afterwards, would be sent to the lots for permanent settlement. On a temporary basis, families would live, and other activities, such as masses, would be carried out in the shed (Cinquantenario..., 2000), in addition to care being provided to the ill, according to records from the João Spadari Adami Municipal Historical Archive (AHMJSA, 1889). And there, in the same way, classes begin in the she, even before the creation or construction of specific spaces.

In 1890, the Inspectors46 registered an official letter explaining that the shed had one class for girls, taught by the Italian teacher Genoveva, and one for boys47, taught by a ‘Brazilian teacher’ (AHMJSA, 1890a). We see that the movement of creation of both occurs concurrently with the first initiatives, evidencing the importance of classes in the residents’ lives, even more so because they made some of the space in the shed, which was already used for other actions, available for the conduction of such teaching activities.

Teacher Sérgio I. de Oliveira’s family stayed a long time in Antônio Prado. He had children up to ten years old attending his classes in the shed (Barbosa, 1980), who later got married and stayed there. Barbosa (1980) explains that Sérgio’s class in 1890 would be public, but this information seems to be distorted by a year of difference, since the evidence leads us to believe in an initially private class. The Commission declared, in an official letter of May 1890, that it was not aware of public classes in the center (AHMJSA, 1890c); there was a suggestion for the appointment of a teacher in July (AHMJSA, 1890a), and only on February 1, 1891, Sérgio was appointed48 to teach the boy’s class in Antônio Prado (A Federação, 1891). Among teacher Sérgio’s students, the list found (AHMJSA, 1890b) indicates the attendance of students aged between seven and 12 years old. Nothing was found about teacher Sérgio’s professional journey prior to 1890.

The teacher’s intense circulation is noteworthy. From 1898 to 1901, Sérgio taught in Bom Jesus (Relatório..., 1898; A Federação, 1901), from 1903 to 1906, he worked in Mato Perso (A Federação, 1903, 1906), in 1907, in São Francisco de Paula, and in 1908, in Criúva (A Federação, 1908a). Lebrun (1935) informs that Sergio was retired as a state public teacher. Although we know little about Sergio’s total period of practice, he and Genoveva were considered Antônio Prado’s first teachers (Barbosa, 1980).

Genoveva De Nale, in 1890, was 13 years old49 when she taught Italian to the girls in the shed. Born in 1877 in Arsiè, Belluno province, she emigrated with her parents and some of her siblings around 188650. Her family would have settled on the Almeida Line, lot 28, far from the seat, on December 15, 1886 (Costa, 2007). The De Nale family possibly never set foot in the shed, as its construction was completed in 1887 (Bertaso & Lima, 1950). Despite the lot being far from the seat, it is possible to see frequent displacements - some of Genoveva’s brothers were born, and in 1892 her sister Cecília died and was buried in the seat51. In 1896, Genoveva was already married and with children. As a teacher, she makes us think about her own education. Having started teaching at the age of 13, immigrated at the age of nine, we question what school process she went through to legitimize her as a teacher and, in this sense, it seems interesting to remember what Luchese and Grazziotin identified.

Lay teachers, some with few years of schooling, who, because of their connection with the community space, because of the need and opportunity that arose, made themselves teachers. Throughout their careers, they found a place in improvement courses, in teacher training schools, or through self-education, building complementary opportunities for professionalization. These are teaching experiences linked to the community space, with a social sense that was valued to the point where teachers were catechists, counselors, community leaders (Luchese & Grazziotin, 2015, p. 354).

Teacher Genoveva stayed many years working as a private teacher in what we call Italian school. When it comes to schools in Antônio Prado and in the region, it is possible to identify, as mentioned by Luchese (2015) and Rech and Luchese (2018), different typologies. There were the so-called Italian schools, with marked differences between urban and rural ones, between those maintained by lay associations or mutual aid, those linked to religious congregations, such as Salesians and Scalabrinians, and finally, ethnic-community schools maintained by the families of a community. In 1908, there were two Italian mixed schools in Antônio Prado, attended by 129 students - 79 boys and 50 girls (Ministero..., 1908, p. 14).

In addition, the public schools are noteworthy, as they were diverse as well. State public schools could have appointed or subsidized teachers52. In the period under study, state schools operated in rented spaces provided by the municipality or the community. According to Werle (2005), subsidies granted by the state to the municipalities were intended to disseminate public education and were paid quarterly from the presentation of certificates of practice, with the knowledge of the sub-intendant or teaching inspector.

Public schools also comprehended those created and maintained by the municipality and municipal grants, which were also identified. Table 1 below presents Antônio Prado’s state public schools, in three different years - 1901, 1903 and 1906. It is possible to see changes in the location of the schools, as well as the teachers’ permanence or absence. We highlight another interesting matter for the period - classes created but not provided. It is the case of the 11th class, which, between 1903 and 1906, was not taught by a state teacher. The non-provision of classes was recurrent throughout RS.

Table 1 Antônio Prado’s schools - 1st entrance - State’s public schools

| Class name | Boy’s or girl’s or mixed | Location | Teacher | ||

| Year | |||||

| 1901 | 1903 | 1906 | |||

| 1st class | Boy’s | Village | João Carneiro de Mesquita | José Victor de Castro | José Victor de Castro |

| 2nd class | Girl’s | Village | Delphina Maeffer | Delphina Maeffer | Delphina Maeffer |

| 3rd class | Boy’s | Nova Treviso | Francisco Bussato | Francisco Bussato | Francisco Bussato |

| 4th class | Boy’s | Castro Alves line | Florencio José da Silva | Florencio José da Silva | Florencio José da Silva |

| 5th class | Mixed | 10 de Julho line53 | Natalina Maeffer | Natalina Maeffer | Natalina Maeffer |

| 6th class | Mixed | Nova Roma54 | Georgina Leitão Neves55 | Maria Antonieta de Almeida e Silva | Vacant |

| 7th class | Mixed | 25 de abril (village suburb) | Julieta Leitão Neves | Luiza Prestes | Virgínia Barbosa de Oliveira |

| 8th class | Boy’s | Almeida line56 | vacant | Caetano Saretta | Luiz Facchini |

| 9th class | Boy’s | Linha Carvalho57 | João Brolhi | João Brolhi | Magdalena Meneguzzo |

| 10th class | Boy’s | Trajano line | nonexistent | Vacant | Joaquim Borges de Castilhos |

| 11th class | Boy’s | Candida line | nonexistent | Vacant | vacant |

Source: Prepared by the authors from Decree No. 366 (1901), Decree No. 591 (1903) and Decree No. 911 (1906).

In Table 1, in addition to relatively constant removals and transfers, we draw attention to the appointment, for instance, of the sisters Natalina and Delphina, both graduates from the normal school of Porto Alegre. Georgina and Julieta were sisters as well. But it was possible to establish other networks of sociability and kinship, as explained ahead. In Table 2, after consultation to several documents58, we present the teachers who worked in Antônio Prado between 1890 and 1910. For the reading of Tables 2 and 3 below, ‘year-year’ means that there are records of the teacher working in the dated period, whereas ‘year, year’ means that, in the first and second referenced years, records of practice were found. For ‘After 1920’, we do not need the end of the practice. As for the use of the acronyms: SMS = Subsidized municipal school; SPS = State public school; SSS = Subsidized state school; SMSS= Subsidized municipal and state school, as the grant was not fixed, varying in the period under study.

Table 2 List of Antônio Prado’s teachers 1890-1910

| Teacher’s name | School Typology | Years for which there are records of the teaching working | Teacher’s name | School typology | Years for which there are records of the teaching working |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sérgio Ignácio de Oliveira | State public school | 1890, 1891 | José Victor de Castro | SPS | 1898-1903, 1907 |

| Genoveva De Nale Scotti | Private | 1890-1913 | Virgínia Barbosa de Oliveira | 1905, 1906 | |

| Florencio José da Silva | SPS | 1899, 1901, 1903, 1905, 1906 1909 and after 1920 | Gaetano Boscato | Private | First decade of 1900 |

| João Carneiro de Mesquita | SPS | 1899-1901 | Antonio Breda | First decade of 1900 | |

| Georgina Leitão Neves | SPS | 1901 | Julieta Leitão Neves | SPS | 1901 |

| Delfina Maeffer | SPS | 1898-1903 | Adélia de Figueiredo Menezes | 1905, 1907 | |

| José Henrique Pereira Porto | Until 1898 | Dorvalino da Silva Cruz | 1907 | ||

| Natalina Maeffer59 | SPS | 1900, 1901, 1903, 1905, 1906-1910 | Licinio Oliveira Mendes Sobrinho | 1907 | |

| Maddalena Meneguzzo60 | SSS | 1902-1903, 1917 and after 1920 | Luiz Machado Rosa | 1907 | |

| Maria Antonietta de Almeida | SPS | 1903 | João Pereira da Rosa | 1908-1910 | |

| Luiza Prestes | SPS | 1903 | Manoel Cardoso de Oliveira Sobrinho | 1909 | |

| Caetano Saretta | SPS | 1903 | Claudino Antonio da Ventura Homem | 1909 | |

| João Brolhi | SPS | 1901, 1903, 1904 | Luiz Facchini | 1906 | |

| Joaquim Borges de Castilhos | 1904, 1909 | Alcides de Mattos Miller | SMS | 1910-1914 | |

| Francisco Busatto | SPS | 1899, 1900, 1901, 1903, 1905, 1906 |

Source: Prepared by the authors, mostly from the documents found in the AHMAP and other documentations investigated and referenced in this research.

The list comprises a total of 29 teachers. With regard to the number of public classes, Antônio Prado, RS, went through an impermanence. Until 1899, there were three classes operating. After that, there were three to nine classes until 1910, with the impermanence being linked to teacher turnover, verified by the years with records of the teachers working in the municipality. Some worked for a short period in a school in the countryside, coming from distant municipalities to teach in Antônio Prado. Even so, the high number of teachers for a small and sparsely populated location is noteworthy, especially when it comes to bureaucratic matters (professional’s hiring and appointment).

Intendant Innocencio would ask the State for financial and human assistance, being favored many times. It should be considered, as reported by Biavaschi (2011), that the intendant would be one of those who most resorted to the government, with patronage and coronelism practices61. This is certainly not a fact restricted to Antônio Prado, as RS was characterized by the expansion of the State’s school network, spread through subsidies in colonial areas (Rech & Luchese, 2018).

Regarding their origin, most of the teachers were not from Antônio Prado, but from Porto Alegre or other municipalities, who had passed sufficiency exams and were sent to the different regions of the State, which partly explains the circulation, removals, and transfer requests. The issue of the teaching and learning process that took place in the classes with Portuguese-speaking teachers and students who were immigrants, or their children deserves attention, as this required adaptations and tactics as to teaching and learning.

Regarding the selection of teachers, we found a list with names and oral tests schedules. Several teachers working in Antônio Prado took oral tests for the selection in July 1905, held at the Secretariat of the General Inspectorate of Public Instruction in Porto Alegre. This was the case on July 9, when Francisco Busatto, Florêncio José da Silva, Joaquim Borges de Castilhos and João Pereira da Rosa participated. Maddalena Meneguzzo and Adélia do Figueiredo Menezes, in their turn, took their test on the 10th, and João Evangelista Andrade Saraiva, on the 14th (A Federação, 1905a). Afterwards, a call was registered for “[...] the provision of rural schools in the State” (A Federação, 1905b, p. 2). Four of the teachers who took the test were working in Antônio Prado in 1905, as shown in Table 1.

With the emancipation, there was an increase in the number of teachers and schools. Also noteworthy is the predominance of teachers of Portuguese origin, which was the case of Claudino Antônio da Ventura Homem, resident in 1909 in Antônio Prado; in 1900, he was teaching a class in Pinheiral, Santa Cruz (A Federação, 1900), then was displaced to Soledade, where he requested to move to Taquara in 1907, which was denied (A Federação, 1907), and after a year, his removal to Antônio Prado was granted (A Federação, 1908c). Claudino’s example was not isolated, and the difficulties of adaptation, or even of settling down in distant municipalities, generated a constant movement of teachers and caused many classes not to be provided for years. In the next table, we present the teachers who worked between the years 1911 and 1920. The reading of the dates and acronyms follows the explanation from the previous table.

Table 3 List of Antônio Prado’s teachers, 1911-1920

| Teacher’s name | School typology | Years for which there are records of the teaching working | Teacher’s name | School typology | Years for which there are records of the teaching working |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jacob Fernando Callegari | SMS | 1911 and 1st half of 1912 | Amabilia De Luchi | SMS | 1914, 1915 |

| Miguel Frigotto | SMS | 1912, 1915, 1917 and after 1920 | AntonioTondello | SMS | 1914, 1915, 1919 e após 1920 |

| Caetano Reginatto | SMS | 1912-1917 | Verginia De Boni | SMS | 1914, 1915 |

| João Tavares de Carvalho | SPS | 1910-1912 | Thereza Antoniutti | SMS | 1914 e após 1920 |

| Affonsina Villas Boas | SPS | 1912-1913 | Attilio Camozatto | SMS | 1915, 1917 |

| Maria Lunardi | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1917 and after 1920 | João Tondello | SMS | 1916 and after 1920 |

| Albano Donadel | SMS | 1913, 1915-1917 and after 1920 | Isidoro Menegat | SMS | 1916 |

| Antonio Camozatto | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1917 | Ercilia Meneguzzo | SMS | 1917, 1919 |

| Josephina Sega | SMS | 1913, 1915-1917 | Lysippo Lisboa | SMS | 1910-1917 |

| Angelo Fantinelli | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1917 | Emilio Mondadori | SMS | 1917 |

| Armando Pinheiro da Costa | 1913 | Rosário Frigotto | SMSS | 1918 | |

| Orozimbo Zanetti | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1918 | Aires Meneguzzo | SMS | 1918 |

| Guido Andreoni | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1919 and after 1920 | Stanislao Polesso | 1918 | |

| Marcelo Fianco | SMS | 1913, 1915, 1917 | Castorina Albernaz | SMSS | 1918, 1919 e após 1920 |

| Pascoal Meneguzzi | SMS | 1914, 1915, 1917 and after 1920 | Erina Dal Molin | SMSS | 1919 |

| Arthur Bogoni | SMS | 1914, 1915 and after 1920 | Dosolina Zatti | SMSS | 1919 |

| Inez Mondadori | SMS | 1914, 1915, 1917 | Josephina Bernardi | SMSS | 1919 and after 1920 |

| Carolina Pansera | SMS | 1914, 1915 and after 1920 | Angelina Mondadori | SMSS | 1919 |

| Normelia Amorim Saraiva | SMS | 1914, 1915 | José Bogoni | SMSS | 1919 |

| José Fialho de Vargas | SPS | 1910-1913, 1916 | Rosa Andreoni | SMSS | 1919 and after 1920 |

| João Evangelista Andrade Saraiva | SPS | 1912, 1915 - 1917 | Teresa Donadel | SMSS | 1919 and after 1920 |

| Carlos Mantovani | SPS | 1915 - 1917 | Justino Vieira Albernaz | SSS | 1917 and after 1920 |

| João Baptista Marchesan | 1915 | Corona Frigotto | SMSS | 1920 | |

| Marcos Baptistin | SMS | 1914-1917, 1919 and after 1920 | Bertha Hornos | SMSS | 1920 and after |

Source: Prepared by the authors, mostly from the documents found in the AHMAP and other documentations investigated and referenced in this research.

The 48 abovementioned teachers started their activities between 1911 and 1920 in Antônio Prado, RS. Thus, the period was characterized by the insertion of immigrants and their children who lived in Antônio Prado. With Decree No. 1895 (1912)62, there was an expansion of schooling due to grants by the State. Moreover, pursuant to Art. 2, the municipality started to apply selection tests, increasing the possibility of a resident taking over, which generated new dynamics in the school environment.

The expansion after 1912 allowed the insertion of more female teachers. Aragão and Kreutz (2010, p. 110) state that “[...] teaching translated into the way out for women who wanted to dedicate themselves to other activities, without having to leave their home and children, since they could work part-time only [...]” , which gradually drove away men, who ended up looking for other professions (Jacques, 2015). The subjects, as proposed by Hall (2006, p. 11, author’s emphasis), can be seen as social beings, as each one will be “[...] formed and modified in a continuous dialogue with the cultural worlds ‘outside’ and the identities which they offer”.

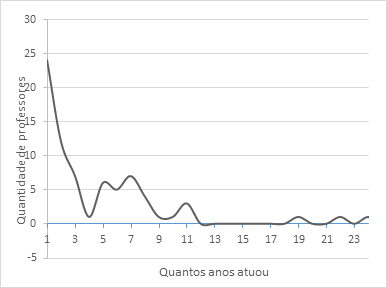

The construction of a network of relationships as a group of ‘teachers’ showed narratives produced collectively and, at the same time, with each subject’s own specific characteristics, linked to the sense of belonging and (de)constructed processes. The previous tables draw attention to the teachers’ short period of practice, and for a more detailed analysis, we present Figure 1.

Figure 1 reaffirms the impermanence in the investigated period. It is possible to see that most teachers worked for short periods, from one to three years, in Antônio Prado. A smaller number stayed from five to seven years, and only a few of them taught ten or more years in that place. Among those who stayed longer, we list Florêncio José da Silva, Maddalena Meneguzzi and Genoveva Scotti, who stayed for more than two decades; Miguel Frigotto, on the other hand, started before Decree No. 1895 (1912) and stayed for at least more than a decade, followed by Maria Lunardi, Albano Donadel, Guido Andreoni, Pascoal Meneguzzi, Arthur Bogoni, Carolina Pansera, Marcos Baptistin, Antonio Tondello and Thereza Antoniutti, who started soon after the decree and appear in the records working in education after 1920 (Almanak Laemmert, 1926).64

To explain this impermanence, we can took the wages into account, but in Antônio Prado we did not identify differences in the amounts that do not depend on the location or whether it is a boy’s, girl’s or mixed class. Between 1912 and 1920, a teacher earned 600$000 réis annually, the same amount as that of a municipal inspector (AHMAP, 1914-1923), monthly, with the salary being paid quarterly. In 1914, for comparison purposes65, intendant Innocencio earned 3:000$000 annually, and the secretary of the Council, 420$000 (AHMAP, 1915).

In addition to wages, bonuses were a common thing, which began still in 1899 and were paid to teachers who could remedy the lack of other teachers in classes that were not filled (AHMAP, 1912). Until 1912, they corresponded to 30$000 monthly, when they rose to 50$000, the same amount as that of other places that also did this in the State (A Federação, 1913a). This last amount was equivalent to another contract, although the teacher could not count on the amount as being fixed. It is possible to see that the salaries of the State’s primary teachers were low (Corsetti, 1998), and in Antônio Prado, delays and even lack of payment66 were common (AHMAP, 1899-1913). In addition to the salary issue, distance from the family, the place to reside, available school supplies, and a whole set of variables involving the classes, students and families, as well as other conditions, may have interfered with one’s decision on staying or not in Antônio Prado, and even on teaching.

Teachers, in addition to teaching itself, had bonds and established relationships with communities. Besides the educational role, it is important to understand the dynamics and complex relationships they mobilized (Bensa, 1998). So is valuing the relationships of these subjects with the social environment, bringing their history and their experiences into that setting (Burke, 1992), because, as Revel (1998, p. 25) explains, “[...] it is not enough for the historian to take up the language of the actors they study, but to make it an indication of a work that is both broader and deeper: that of building plural and plastic social identities that operate through a close network of relationships”.

Reducing the scale of observation while thinking about teachers allows “[...] understanding how social configurations and processes are constituted, through an intensive and close study of their movements, agents and sources” (Aquino, 2019, p. 28). The ties found between the subjects and local political situations is one point. Teacher Caetano Reginatto, for instance, worked in Nova Roma in the 1910s; additionally, he was a postal agent (Almanak Laemmert, 1917), became a delegate (Relatório..., 1920), was Innocencio de Mattos Miller’s vice-intendant, then took over as intendant (Biavaschi, 2011). Caetano was Antônio Prado’s 2nd intendant. Reginatto was part of a large family with good financial conditions. He was one of the youngest children of Antonio Reginato II and Lucia Gazzola. Born in 1885 in Italy, he immigrated as a child. In Brazil, he married Edviges Araldi in 1913 (Antônio Prado (RS), 1913). During the 1893 Federalist Revolution, his father was murdered (Barbosa, 1980), and most of the children were young. A possible personal motivation for the position that Caetano took in relation to politics.

He also participated in actions outside the schools, making his presence felt and acting on different fronts, such as religious events (Barbosa, 1980), and organizing political celebrations in the Nova Roma district. He achieved notoriety and became a speaker at political events, being also permanently inserted in public offices. As Antonio Prado’s intendant, there was an indication of special attention to the school, with the creation, for instance, of the Teacher Ulisses Cabral School Group (Barbosa, 1980).

In addition to Caetano, other teachers had ties with politics. Joaquim Borges de Castilhos suffered with political fights (O Brazil, 1910), which Innocencio’s vice-intendant, at the time intendant Cristiano Ziegler, also left with injuries67. José Victor de Castro was another presence in the records, as he wrote to the government reporting on the political situation of the municipality and, just as Caetano, was present at the Intendance’s events. He served as a teacher from 1898 to 1907, becoming an inspector the following year. Finally, he resigned after being appointed a civil servant (A Federação, 1908b), a position he held for at least a decade (Almanak Laemmert, 1917), and one might think that moving to different roles meant better remuneration. His link and permanence with the municipality can also be explained by the fact that his children stayed in Antônio Prado.

In the case of teacher José Fialho de Vargas, he was secretary of the Intendance at the same time as he taught. He married a resident and, after 1920, took over the direction of the local School Group, which was supported by the intendant and former teacher Caetano Reginato. Thus, it is possible to see a dynamic network of sociabilities in which subjects play some roles and move around, with some of their actions being justified or supported due to the nuances found when we look at their past or their ties with the community and the environment.

It is noticed that “[...] there is an intrinsic relationship between major facts and ordinary events, often disregarded by historical analyses. Or that were so for a long time” (Santos, 2018, p. 28), and for this reason, the same author explains that “[...] the analysis of political and social constructions cannot be restricted only to the sphere of major events [...]”, so we reinforce the look at minor facts and a critical, differentiated interpretation in order to understand school subjects.

Seeking to establish networks of relationships among teachers, we think about what Santos (2018) calls ‘constitutive modalities’ in his work to understand social networks. He supports the existence of four modalities: party relationships, confessional religious relationships, economic and family relationships, and among them, within the group, at least one would unite individuals for the sense of belonging. We focus on the analysis of family relationships, one of the evidenced modalities, to reflect on teachers and the constitution of this network.

It is known that the “[...] insertion of the family network within the large social network is a way of more securely supporting the pursuit of interests and needs, both individual and collective” (Santos, 2018, for. 90). Regardless of the order of influence, we are interested in establishing connections that will create a link. Thus, we identified that teacher Antonio Tondello married his former student Josephina Bernardi, who also became a teacher later. Antonio was the brother of teacher João Tondello, who married Tereza Antoniutti, who also became a teacher. Tereza Antoniutti was the sister of João Antoniutti, who married Maria José, teacher José Victor de Castro’s daughter.

Other networks can be analyzed. Genoveva De Nale Scotti’s nephew, Angelo Scotti, was brother-in-law of Edviges Araldi, Caetano Reginato’s wife; another niece of Genoveva, Giuseppina, was married to Antonio Citton, brother of Pelegrina, who was married to José Fialho de Vargas; in addition to João Carneiro de Mesquita, who was married to teacher Delfina Maeffer (A Federação, 1910). This network of relationships will remain linking the location not only for the investigated period, as it branches out. The cases discussed serve as an example for us to understand the dynamics of the social setting.

In Antônio Prado, teaching is clearly inherited, that is, different generations take on the role of teachers. The children of teacher Michele, Rosário and Corona, chose the same profession. Similarly, Maddalena Meneguzzo (born Canale) and her children Ercilia and Aires also became teachers; Castorina Albernaz (born Vieira) and her son Justino Vieira Albernaz were teachers as well.

Another constitutive aspect was the proximity between teaching and Catholicism. Most teachers were catechists, acolytes68, Eucharist ministers, or had other roles, such as churchwardens69. For instance, within the scope of the religious celebration in honor of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, one of the main activities was coordinated by one of the female teachers. The newspaper announced that “[...] on the 14th and 15th, there was a play directed by the acting artist Mrs. Genoveffa Scotti; she was assisted by volunteers and skilled dilettantes who staged the wonderful drama ‘Catholic Heroes, S. Clotilde and the conversion of Clodoveo’” (Il Colono Italiano..., 1912, p.2, author’s emphasis, our translation)70. Teaching and practicing Catholicism, being ‘devoted’, was one of the representations of a good teacher, which was deemed important and expected by the community. Another example that was printed on the pages of the newspaper Il Colono Italiano was the news that “[...] in addition to being a diligent teacher, teacher [Michele] Frigotto is also a practical Catholic in every way; and I will not say how appreciable this gift is today, especially for a teacher” (Il Colono Italiano..., 1913, p. 2, our translation).71

Another tie that we identified among several teachers in Antônio Prado was with newspapers. Some acted as correspondents, as ‘information bearers’ of the social medium, some sent letters, manifestos. Teachers José Fialho de Vargas and João Evangelista Saraiva wrote in the newspaper O Pradense, founded in 1916 in Antônio Prado, with Saraiva being described by Barbosa (1980, p. 105) as “[...] the measured preacher of good manners and school matters”72. Antônio Tondello was a propagandist and distributor of Correio Riograndense in Capela São Roque, where he lived and made his residence available to families for their children to read the newspaper’s articles (Correio Riograndense, 1964). Oftentimes, newspapers such as A Federação or Il Colono, with news about Antônio Prado, were created from letters exchanged with local teachers. As identified by Luchese (2015, p. 416, author’s emphasis),

The vast majority of the first teachers in the Italian Colonial Region had no pedagogical training. Many of those who taught [...] had primary education only. However, they were, for the most part, the best instructed in the community, and this condition, added to that of them being ‘masters’, brought about prestige, respect and community leadership. Many were the teachers who took on, within the social setting in which they lived, a central role in religious, petition and organization matters, becoming representatives of that group, when not local leaders. These were the representations produced about being a teacher.

Of the various representations and roles took on by the teachers in the communities where they worked, in addition to those already mentioned, they were expected to exhibit an unblemished behavior, represented in attitudes and ways of being, dressing and acting. Teaching as a vocation, the teacher as “[...] mediator with a sacred mission received from God and which should be placed at the service of the community” (Kreutz, 2004, p. 160), educating children in reading, writing, counting and praying, which was expected and desired by Antônio Prado’s families.

Further considerations

About the itineraries and processes of constitution of being a public teacher, we noticed that most of those who were subsidized by the State or municipality chose teaching because of the opportunity that arose. Among those appointed, several were identified as having been educated in the capital and stayed in Antônio Prado for relatively short periods.

The intense circulation - through transfers, removals - of teachers allows us to think about cultural negotiations and different realities of teaching and learning to which the teachers needed to adapt. Gradually, the grants allowed the municipality and/or the State to offer a quarterly amount for them to teach, and most of those who took it were people living in Antônio Prado. There is also evidence, to be further investigated, that several teachers had, in addition to teaching, other professional roles.

In the case of Antônio Prado, we showed that two schools started operating in the space of the hut that sheltered the immigrants. Some of the teachers’ journeys, from the available documentation, allowed us to delve deeper, such as those of Sérgio Ignácio de Oliveira, Genoveva De Nale Scotti, Caetano Reginatto, José Victor de Castro, and José Fialho de Vargas. We recognize that “a reading is trailed amid fractures and dispersion, questions are forged from silences and babbles” (Farge, 2009, p. 91), and the complexity of life and of the teaching experience appears reduced to some clues of those past times, when rural classes were improvised, as much as many of their teachers were.

Some other pieces of evidence of the teachers’ itineraries, permanence in the different positions they held, some of their family and social relationships, wage issues, the representations of being a teacher in a colonial center, and its first years as a municipality in the Gaucho Highlands are journeys that share similarities with so many others in the Rio Grande do Sul and even the Brazilian context, but there are singularities. Finally, for a small town, the number of teachers, many from other locations, is noteworthy, in addition to the impermanence as to their length of practice, which was a striking characteristic of this schooling period in Antônio Prado (Bernardi, 2020). We noticed networks of relationships and power games that possibly impacted their insertion in teaching activities. Furthermore, several teachers had very active political and religious lives. Also, being a teacher represented, for women, the possibility of ascending to an accepted and recognized profession.

We conclude by considering that the teachers were linked to the environment in which they worked, being represented as important subjects, bearers of knowledge and ways of being required from role models, subjects valued for being teachers, but also for taking on other roles in a religious, political or cultural dimension that was meaningful for those human groups.

REFERENCES

Albuquerque Jr., D. M. (2019). O tecelão dos tempos (novos ensaios de teoria da história). São Paulo, SP: Intermeios. [ Links ]

Almanack escolar do Rio Grande do Sul. (1935). Diretoria Geral da Instrucção Pública. Edição Official. Porto Alegre, RS: Livraria Selbach de J. R. da Fonseca & Cia. [ Links ]

Almanak Laemmert. (1917). Annuario comercial, industrial, agrícola, profissional e administrativo, para 1917 (Vol. 2). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Officinas Typographicas do Almanak Laemmert. [ Links ]

Almanak Laemmert. (1926). Annuario comercial, industrial, agrícola, profissional e administrativo, para 1926 (Vol. 4). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Officinas Typographicas do Almanak Laemmert . [ Links ]

Antônio Prado: como ele foi, como ele é. (1972, 30 de julho). Panorama Pradense. p. 8-9. [ Links ]

Antônio Prado (RS). Cartório de Registro Civil. (1913, 10 de dezembro). Registro de casamento de Caetano Reginato e Edviges Araldi. 82:154. [ Links ]

Antônio Prado (RS). Cartório de Registro Civil. (1896, 4 de dezembro). Registro de casamento de Antonio Scotti e Genoveffa De Nale. 63:41. [ Links ]

Aquino, I. S. (2019).Tecendo um mundo desigual: análise de redes de compadrio na freguesia de Viamão (1759-1769). In A. Karsburg, & M. I. Vendrame. Variações da micro-história no Brasil: temas, abordagens e desafios (p. 27-50). São Leopoldo, RS: Oikos. Recuperado de: http://oikoseditora.com.br/new/obra/index/id/946 [ Links ]

Aragão, M., & Kreutz, L. (2010). Do ambiente doméstico às salas de aula: novos espaços, velhas representações. Revista Conjectura, 15(3), 106-120. Recuperado de:http://www.ucs.br/etc/revistas/index.php/conjectura/article/view/515/400 [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado [AHMAP]. (1914-1923). Contrato de professores. Paginação irregular. [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado [AHMAP]. (1899-1913). Registro de correspondências da Intendência Municipal de Antônio Prado de 11.02.1899 a 10.02.1913. [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado [AHMAP]. (1912). Relatório apresentado ao Conselho Municipal em 20 de novembro de 1911 e Lei do Orçamento para o exercício de 1912. Caxias do Sul, RS: Typ. Mendes & Filho. [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal de Antônio Prado [AHMAP]. (1915). Relatório apresentado ao Conselho Municipal em 12 de outubro de 1914 e Lei do Orçamento para o exercício de 1915. Caxias do Sul, RS: Typ. Mendes & Filho . [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami [AHMJSA]. (1889, 29 de setembro). Arquivo da Diretoria da Colônia Caxias e da Comissão de Terra e Medição de Lotes. [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami [AHMJSA]. (1890a, 03 de julho). Arquivo da Diretoria da Colônia Caxias e da Comissão de Terra e Medição de Lotes . [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami [AHMJSA]. (1890b, 20 de agosto). Arquivo da Diretoria da Colônia Caxias e da Comissão de Terra e Medição de Lotes . [ Links ]

Arquivo Histórico Municipal João Spadari Adami [AHMJSA]. (1890c, 23 de maio). Arquivo da Diretoria da Colônia Caxias e da Comissão de Terra e Medição de Lotes . [ Links ]

Barbosa, F. D. (1980). Antônio Prado e sua história. Porto Alegre, RS: EST. [ Links ]

Bensa, A. (1998). Da micro-história a uma antropologia crítica. In J.Revel (Org.), Jogos de escalas: a experiência da microanálise (p. 39-76). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fundação Getúlio Vargas. [ Links ]

Bernardi, M. (2020). Processo de escolarização em Antônio Prado (1886-1920):culturas e sujeitos (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul. Recuperado de: https://repositorio.ucs.br/xmlui/handle/11338/6728 [ Links ]

Bernardi, M., & Luchese, T. A. (2020). A taxa de alfabetização em Antônio Prado, Rio Grande do Sul (1895-1920). Revista Educação em Questão, 58(56), 1-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2020v58n56ID20030 [ Links ]

Bertaso, H. D., & Lima, M. A. (1950). Álbum comemorativo do 75º aniversário da colonização italiana no Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, RS: Revista do Globo. [ Links ]

Biavaschi, M. A. C. (2011). Coronelismo na região colonial italiana: Antônio Prado (1903-1928). Historiae, 2(3), 171-186. Recuperado de: https://periodicos.furg.br/hist/article/view/2617/0 [ Links ]

O Brazil. (1910, 3 de setembro). p. 1. [ Links ]

Burke, P. (1992). A escrita da história:novas perspectivas. São Paulo, SP: EdUNESP. [ Links ]

Cinquantenario dela colonizzazione italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud. (2000).(Vol. 2). Porto Alegre, RS: EST . [ Links ]

Il Colono Italiano, OrganoDegliInteressiColoniali. (1912, 12 de janeiro). p. 2. [ Links ]

Il Colono Italiano, OrganoDegliInteressiColoniali . (1913, 5 de abril). p. 2. [ Links ]

Correio Riograndense. (1964, 25 de novembro a 2 de dezembro). p. 3. [ Links ]

Corsetti, B. (1998). Controle e ufanismo: a escola pública no Rio Grande do Sul (1889/1930) (Tese de Doutorado). Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria. [ Links ]

Costa, R. (2007). Povoadores de Antônio Prado. Porto Alegre, RS: EST Edições. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 366, de 31 de janeiro de 1901. (1901, 2 de fevereiro). A Federação: Órgão do Partido Republicano (RS). n. 29. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 591, de 31 de janeiro de 1903. (1903, 6 de fevereiro). A Federação: Órgão do Partido Republicano (RS). n.32. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 911, de 21 de maio de 1906. (1906, 21 de maio). A Federação: Órgão do Partido Republicano (RS).n. 117. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 1895, de 23 de dezembro de 1912. (1913). In Relatório apresentado ao Sr. Dr. A. A. Borges de Medeiros, presidente do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, pelo Dr. Protasio Antonio Alves, Secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior e Exterior (p. 288-290). Recuperado de: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/189956. [ Links ]

Farge, A. (2009). O sabor do arquivo. São Paulo, SP: EDUSP. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS). (1891, 2 de fevereiro). ano 8, n. 28, p. 2. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1900, 24 de fevereiro). ano 17, n. 43, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1901, 2 de fevereiro). ano 18, n. 29, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1903, 6 de fevereiro). ano 20, n. 32, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1905a, 24 de julho). ano 22, n. 171, p. 3. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1905b, 08 de agosto). ano 22, n. 184, p. 2. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1906, 21 de maio). ano 23, n. 117, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1907, 03 de junho). ano 24, n. 129, p.1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1908a, 25 de julho). ano 25, n. 178, p. 2. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1908b, 06 de agosto). ano 25, n. 183, p.1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1908c, 19 de novembro). ano 25, n. 270, p. 2. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1909, 16 de setembro). ano 26, n. 215, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1910, 10 de novembro). ano 27, n. 260 , p. 2 [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1913a, 23 de outubro). ano 30, n. 246, p. 1. [ Links ]

A Federação: Orgam do Partido Republicano (RS) . (1913b, 23 de novembro). n. 273, p. 6. [ Links ]

Ginzburg, C. (2003). Mitos, emblemas, sinais. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE]. (2020). Censo demográfico, estimativa para 2020. Recuperado de: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/rs/antonio-prado.html [ Links ]

Hall, S. (2006). A identidade cultural na pós-modernidade. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: DP&A. [ Links ]

Jacques, A. R. (2015). O ensino primário no colégio Farroupilha: do processo de nacionalização do ensino à LDB nº 4.024/61 (Porto Alegre/RS: 1937/1961) (Tese de Doutorado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. Recuperado de: http://tede2.pucrs.br/tede2/handle/tede/6455 [ Links ]

Kreutz, L. (2004). Professor paroquial: magistério e imigração alemã. Pelotas, RS: Seiva. [ Links ]

Levi, G. (2017). O pequeno, o grande e o pequeno. Revista Brasileira de História, 37(74), 157-182. [ Links ]

Luchese, T. Â. (2015). O processo escolar entre imigrantes no Rio Grande do Sul. Caxias do Sul, RS: EDUCS. [ Links ]

Luchese, T. Â., & Grazziotin, L. S. (2015). Memórias de docentes leigas que atuaram no ensino rural da Região Colonial Italiana, Rio Grande do Sul (1930 - 1950). Educação e Pesquisa.41(2),341-358. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-97022015041795. [ Links ]

Ministero degli Affari Esteri. (1908). Annuario dele scuoleitalianeall’estero: governative e sussidiate. Roma, IT: Tipografia del Ministero degli Affari Esteri. [ Links ]

Rech, G. L., & Luchese, T. A. (2018). Escolas italianas no Rio Grande do Sul: pesquisa e documentos. Caxias do Sul, RS: EDUCS . [ Links ]

Relatório apresentado ao Sr. Dr. Antonio Augusto Borges de Medeiros, presidente do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, pelo Dr. João Abbott, Secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior e Exterior: quadro de escolas públicas da 3ª região escolar. (1898). Recuperado de: htps://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/163963 [ Links ]

Relatório apresentado ao Sr. Dr. A. A. Borges de Medeiros, presidente do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, pelo Dr. ProtásioAntonio Alves, Secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior e Exterior. (1920). (Parte I, p. 367). Recuperado de: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/191570 [ Links ]

Relatório apresentado ao Sr. Presidente do Estado, Sr. Borges de Medeiros, pelo Secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior, ProtásioAntonio Alves. (1913). Porto Alegre, RS: Oficinas Graficas da Livraria do Globo. [ Links ]

Relatório da Inspetoria Geral de Terras e Colonização apresentado a S. Ex. Sr. Conselheiro Antônio da Silva Prado, ministro e secretário de Estado de Negócios da Agricultura, Comércio e Obras Públicas pelo tenente-coronel Francisco Barros e Accioli Vasconcelos, inspetor geral. (1887). [ Links ]

Revel, J. (1998). Microanálise e construção do social. In J. Revel (Org.), Jogos de escalas:a experiência da microanálise (p. 15-38). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Fundação Getúlio Vargas . [ Links ]

Santos, R. L. (2018). Tramas enlaçadas: política, religião e educação no Rio Grande do Sul na primeira metade do século XX. Porto Alegre, RS: Fi. [ Links ]

Werle, F. O. C. (2005). O nacional e o local: ingerência e permeabilidade na educação brasileira. Bragança Paulista, SP: Ed. Universidade São Francisco. [ Links ]

37Classes is the term of that time to refer to a group of students at different levels of learning and that has a teacher in a room.

38The title contains the ‘male and female teachers’ nomenclature but, throughout the text, we chose the term ‘teachers’. Despite this choice, we refer to both men and women and stress that the majority of the teachers were progressively female.

39The installation of the Marist School set a different period for schooling in Antônio Prado, RS. At the same time, we see the expansion of public schools and a greater municipal participation in educational investments.

40Antônio da Silva Prado was affiliated to the Conservative Party of São Paulo during the imperial period. He was an assembly man and senator in the Empire, as well as a minister. With the Republic, he held the position of intendant of São Paulo.

42Innocencio de Mattos Miller, one might say, had quite close ties with high authorities ruling RS. For more details, see Biavaschi (2011), who investigated the relationship between coronelism and intendant Miller.

43Nowadays, the locality calls itself ‘The most Italian city in Brazil’, for having a high percentage of descendants and the largest architectural group of houses from the Italian immigration period in Brazil, listed by the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute [Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional] (IPHAN).

44Currently, Antônio Prado remains a relatively small town, with an estimated population of 13,405 inhabitants (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística [IBGE], 2020).

45Chapels were small churches built, most of the time, in a joint effort by the families of a locality. The social life of the community revolved around the chapel, with cemetery, school, headquarters and some businesses.

46The inspectors assessed the establishment of the Italian colonies and were part of the Lots and Land-Measurement Comission, linked to the Province.

47We preferred to keep the nomenclature and sex differentiation of the classes, which helps understand their future, but also allows reflecting on the configuration that was established in each one. In Antônio Prado, a large portion of the classes in the beginning were for boys or girls only; in the following decades, mixed classes appeared, that is, with both boys and girls together (Bernardi, 2020).

48Perhaps it is possible to think that the appointment of Sérgio rather than Genoveva to the public school is related to the language taught, since Genoveva taught in Italian, and Portuguese was required for public classes (Rech & Luchese, 2018).

49Age calculated from the civil marriage between Genoveva and Antonio Scotti on 04/12/1896, when she declared to be 19 years old and had already two children. During the act, she did not declare her profession. The death of her first child was reported, which occurred in November 1894, at just three days of age (Antônio Prado, RS, 1896).

50Date estimated from her arrival in Antônio Prado, RS. Genoveva’s uncles, Bortolo and Antônio Fusinato, emigrated in March 1886; having arrived in Rio de Janeiro on April 11, they headed to Caxias do Sul, settling on April 27. They later moved to Antônio Prado. Maria Teresa Fusinato’s parents were present in Antônio Prado after 1900, without records of their passage through Caxias do Sul. So it is possible that her brothers immigrated before. Maria Teresa, her husband Giovanni De Nale and their children may have emigrated with Maria Teresa’s parents.

51There are dating difficulties, as Antônio Prado’s civil registries begin after 1895. The dates presented are from late or parish records. It is also worth considering the possibility that there is no cemetery on the Line for Cecília’s burial in the seat.

52The criteria for distributing grants consisted of verifying attendance, class location, and the teaching conducted by the teacher. As an educational public policy for the colonial regions of RS, the grants were considered necessary by the secretary Protásio Alves. Due to the financial difficulty in creating the necessary number of classes in the colonies, if they have to be provided by regular teachers, as well as in obtaining qualified teachers, in remote regions, with small salaries being noticed, in addition to the fact that it was easy to obtain, in the very colonies, people sufficiently trained to assist in that elementary learning, without prejudice to other occupations, and contenting themselves ever since with a modest subsidy from the State, the report concluded that it was rare in those localities “[...] to find someone who wishes to receive more than these fundamental lights [...]”, and finished its defense of the provision of subsidies stating that to “[...] assist in such learning, the teacher’s dedication is more valuable than their illustriousness” (Relatório... , 1913, p. VI). Grants were common and in considerable number in Antônio Prado.

53In 1906, the fifth class was located in Suburbia, and the seventh class was on the 10 de Julho Line, as per Decree No. 911.

55Georgina Neves Campos Netto graduated from the Normal School at the end of 1899; after not going to Lavras, on May 30, 1900, she was appointed to the sixth class in Nova Roma. In the years following her assignment to Antônio Prado, she began to teach classes in Montenegro and Caxias do Sul. At the end of 1934, she had already been in the profession for 32 years (Almanack..., 1935).

58We are aware that there may be other teachers who worked at Antônio Prado’s schools, mainly in private education. Based on the documents, we sought to list them as thoroughly as possible, since there is no synthesis of all teachers.

59State public teacher. “Pursuant to Decree No. 293 of February 8, 1900, she began to teach the 5th class, a mixed, 1st entrance class, on the 10 de Julho Line, municipality of Antônio Prado, toking over 2 de Março next. Having passed the urban examination to which she subjected herself, though having applied for the rural one, she was appointed to effectively conduct the 5th class, a mixed group in the suburbs of that village, to which she moved on September 4 of the following year, by Decree No. 972. On October 4, 1911, she was removed, at the request of the 9th class in Couto, municipality of Santa Cruz, taking over on the following November 14. [...] She completed 35 years, 2 months and 11 days of effective service on December 31, 1934” (Almanack..., 1935, p. 107).

60State public teacher. “Provisionally appointed on 14-3-1902, pursuant to article 36 of the Regulation. She took over on 15-04-1902. On 14-4-1926, she began to serve as an attaché to Antônio Prado’s School Group. She received the fourth-part part special bonus, as of 28-5-1928 (Act No. 552 of 6-12-1928). She completed 31 years, 7 months and 3 days of effective service, on December 31, 1934” (Almanack..., 1935, p. 118).

61Patronage is a practice in which there are rewards in exchange for favors. According to Biavaschi (2011), it is possible to see in the letters and archived records of intendant Innocencio the numerous requests for favors, especially when the letters were addressed to the president of the Province of Rio Grande do Sul, Borges de Medeiros. In the case of coronelism, a common practice in the First Republic, the authority of the colonels starts to control the political process. In the case of intendant Innocencio, he frequently inserted people, some relatives or acquaintances, in strategic places that helped him maintain the political situation and consensus.

62It was justified by the “[...] need to disseminate primary education and nationalize education among rural populations of foreign origin” (Relatório..., 1913, p. 288).

63The figure was produced from the previous tables. There may be differences in length of work due to a lack of available documentation, but it is possible to establish information security, since most teachers would be replaced at the school where they worked.

64In the documentation, we identified that some of the teachers continued their careers until the 1940s, as was the case with Antônio Tondello. Impermanence is greater at the end of the 19th century and in the first two decades of the 20th century.

65Another way of comparing wages is to think that a new-bean sack in 1913 was sold for 14$000 réis, and corn was sold for 5$000 réis a sack (A Federação, 1913b).

66We are referring to the funds coming from the State, evidenced in the records of the Intendance by letters recurrently asking the State Public Instruction Inspector to forward late payment orders for teachers. In some cases, such as that of teacher Jacob Fernando Callegario, the issue went on for a year, until he asked to resign from his position (AHMAP, 1899-1913).

67It is possible to see in Antônio Prado, RS, throughout the period, tension, fights and some deaths due to political issues. We reassessed Innocencio’s permanence in the administration for more than two decades, added records of fraud in elections and so many other facts to understand the dynamics that politics produced in that space.

69Churchwardens were members of the parish council and had the role of assisting the church in the administration of services and events in the community.

70“nei giorni 14 e 15 vi fu rappresentazione teatrale direta dalla provetta artista signora D. Genoveffa Scotti che coadivata da volentierosi e abili diletante interpretarono a meraviglia il drama ‘Eroi cattolici S. Clotilde e Conversione di Clodoveo’”.

71“[...] “Il Professor Frigotto oltre ad essere un diligente insegnante é purê un cattolico pratico a tutta prova; e non diró io quanto sia apprezzabile questa dote oggi specialmente per un insegnante”.

72We regret that no copies of the newspaper O Pradense were found. Without a doubt, the matters related to teachers and education were addressed by those who were part of the newspaper.

82How to cite this article: Bernardi, M. C., & Luchese, T. A. In the course of teaching: itineraries of public teachers in Antônio Prado, Rio Grande do Sul (1885 - 1920). (2022). Brazilian Journal of History of Education, 22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v22.2022.e197 This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4) license.

Received: March 05, 2021; Accepted: August 27, 2021; Published: December 13, 2021

texto en

texto en