Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.23 Maringá 2023 Epub 30-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v23.2023.e275

DOSSIER

Revista Escolar as a space for dispute and legitimization of the discourse: convergence in the divergence of ideas (1925-1927)

1Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Guarulhos, SP, Brasil.

The main objective of this article is to analyze the editorial formula of Revista Escolar (1925-1927), financed by the General Directorate of Public Instruction of São Paulo, to understand the shifts in the reading model and debt formation of debates about educational reconfiguration in the 1920s, undertaken by and in the imagined communities of São Paulo educators. It is concluded that the Revista circulated divergences on educational policy and convergences on health policy in São Paulo.

Keywords: paulista education; materiality of printed material; educational debate; revista escolar

O objetivo deste artigo é analisar a fórmula editorial da Revista Escolar (1925-1927), financiada pela Diretoria Geral de Instrução Pública de São Paulo, para compreender os deslocamentos do modelo de leitura e de formação debitária da reconfiguração dos debates educacionais, na década de 1920, empreendidos pela e na comunidade imaginada dos educadores paulistas. Conclui-se que a Revista fazia circular divergências sobre a política educacional e convergências sobre a política sanitária em São Paulo.

Palavras-chave: educação paulista; materialidade do impresso; debate educacional; periódico escolar

El objetivo principal de este artículo es analizar la fórmula editorial de la Revista Escolar (1925-1927), financiada por la Dirección General de Instrucción Pública de São Paulo, para comprender los cambios en el modelo de lectura y la formación de deudas de la reconfiguración de los debates educativos de la década de 1920, emprendidos por y en las comunidades imaginadas de educadores paulistas. Se concluye que la Revista difundió divergencias sobre política educativa y convergencias sobre política de salud en São Paulo.

Palabras clave: educación paulista; materialidad de la imprenta; debate educativo; revista escolar

Introduction

Revista Escolar (RE)17 - 1925-1927 - is part of a set of publications recognized by historiography (Catani, 2003; Nery, 2009; Carvalho, 2003b) as the one that shaped the educational field of São Paulo: A Eschola Publica (1893 -1897), initiative of model school teachers; Revista do Ensino, organ of the 'Beneficent Association of State Public Teachers' (1902-1918); the Revista da Sociedade de Educação (1923-1924); and Educação (1927-1930). For the historians, together with the installation of normal and primary schools and with associations of teachers (graduated by the new institutions), these journals produced an agenda of debates inherent to the construction of the schooling process in the State of São Paulo and disseminated knowledge and practices, which, in turn, fostered the primary school culture of the state network.

However, RE is a controversial journal. Its contemporaries, especially the generation that was known as the New School, attributed to its pages the sign of retrogression, conservatism and tradition that should be overcome. For them, the RE defended pedagogical precepts and teaching practices that should be modernized. The active school, prescribed until then, no longer met the advances in Educational Sciences, harming the ways of teacher training and the renewal of learning necessary for the formation of Brazilian citizens. At the center of the criticism was precisely the reading and training model offered to the target audience: pages and pages of lessons and lesson models to be copied (Azevedo, 1937). As for the historians who dedicated themselves to RE, their pages did not contain only the tradition of the São Paulo school and its lesson models; there were also authors and theories of education defended by the new generation of educators (Nery, 1993), as well as the entire new corollary established by the new theories of Hygiene, supported by the developments of the medical sciences (Silva, 2019).

In our approach, the printed material is taken as cultural objects in its material form: RE is problematized as a product of determined social practices, either by the technical conditions of its production, or by the social rules that order the discursive regimes. RE's materiality is marked by the technical and industrial processes employed in its production and editing. These processes are implicated in the rules of economic exchange (they are goods) determined by the conditions of their time and by the social and symbolic rules of the clerical culture (good writing, decorum and gender classifications of texts, among others) according to the idealized recipient by their producers (authors and editors) (Hansen, 2019).

Along the lines of Carvalho and Toledo (2007), materiality becomes one of the central dimensions of the historiographical operation and of the documental criticism carried out by this study: the discourses are examined from the practical formalities of their production, their circulation and their possible appropriations. From this perspective, the multiple material devices through which discourses circulate as determined cultural products are problematized. In the case of this work, it is about education, schooling, forms of socialization of the new generations, good teaching, etc., which all influence this investigation within the scope of an archeology of cultural objects (Carvalho, 2003b).

Periodical publications - such as RE - or book collections establish, since their launch, an editorial formula (editorial standard), organized by textual and editorial devices, to which the texts chosen to compose their editorial plan are submitted (Toledo, 2020). This pattern includes the coverage (cover, spine, back cover) of the journal, the internal structure (a model is established under which the published texts are submitted) and the dissemination strategies (Toledo, 2020). This formula, on the one hand, constitutes the identity of the printed object itself and, on the other hand, the editorial strategies mobilized delimit borders between fields of knowledge. In addition, they operate the inclusion and exclusion of authors, prescribe the location of titles in different fields of knowledge, prescribe or censor cultural practices - whether in the school environment, or in the spheres of extra-school political and social sociability, as well as situate their audience in the reading space they design (Toledo, 2013).

Pedagogical journals and the Brazilian republic

In his description of the cultural life of the city of São Paulo at the end of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century, Cruz (2000) points out that the collective spaces of the literate elites are expanding: recreational and literary associations, charities, sports associations, instructive and also those of crafts expand. These collective spaces, previously almost exclusively male, are diversified. This expansion is due to the significant increase in graphic arts in the city, which now offer cheaper and higher quality services. In addition, there is the structuring and regularization of postal and telegraph services, provided by the development of the railways, which allowed, in a stable way, the distribution of forms, including the systematization of subscription services. Also, it is during this period that some booksellers start their business and aid in the distribution of the periodical press, multiplying the access to printed materials (Cruz, 2000).

The process of structuring this production network made it possible to multiply products: books; collections; periodicals (illustrated, literary, specialized in crafts, politics, or economics); leaflets; almanacs; leaflets; newspapers (large or small press); and a diversification of notebooks for writing (with guidelines, for calligraphy, grids, for accounting, etc.) (Cordova, 2016). This increase in printed material indicates the diversity of readers (and writers) and strategies for seeking new markets, such as those for children, women, workers, among other groups that were not yet fully inserted in literate culture. This expansion of possibilities was also accompanied by the dissemination of increasingly hegemonic representations that “[...] associated the book/reading and the school with symbolic and mental attitudes that would allow the country's progress, whether as civilizing practices or as practices disciplinary and cultural control18” (Carvalho & Toledo, 2021, p. 13).

It is in this effort that the invention of a new imagined community is articulated (Anderson, 2008): that of primary school teachers. In this sense, the debate on recruitment and training strategies for new professionals in teaching the culture spread by the school (now teachers instead of schoolmasters) is established, sometimes with consensus, sometimes with fierce disagreements. This also applies to the models of normal schools, as well as to the practices to be disseminated, which, at the limit, would manufacture the identity of this new class of professionals and guide the political debate (for example, in the Legislative Assembly) and the debate of the nascent educational field (Carvalho & Toledo, 2021).

The printed material produced by and for this craft corporation became fundamental instruments of intervention in ordering the new imagined community19, outlining the strength of the representations in dispute about its traits, practices, knowledge and identities. The printed material will produce and disseminate the lexicon/jargon (either the conceptual set, or the set of maxims or catchphrases) of this community, as well as its problems, its objects and its ethics. As Carvalho (2003b, p. 104) reminds us, “[...] the printed material will function as a device for regulating and adapting the discourse and the pedagogical practice of teachers20”.

For De Certeau (1998), text producers refer to the idea that the reader is produced by the text. This corollary is present in the investment policies for print production, which intend to mold the reader to certain policies and practices. Therefore, another task assigned to the many pedagogical journals was to use them to support teacher training. These journals used their pages as a general uses his troops at war, that is, operating in a disputed, belligerent and hostile field, giving vent to the ideas and thoughts of those who elaborate them (Silva, 2019).

Therefore, it is necessary to analyze these printed initiatives in an articulated way to the installation policies of primary and normal schools in the State of São Paulo. According to Carvalho, the first republicans from São Paulo, who promoted the institutionalization of primary school in the State in the 1890s and 1900s, appropriated concepts of 'modern pedagogy': a 'practical pedagogy', in which 'teaching to teach' is to provide 'good molds' (Carvalho, 2001, 2006). Thus, they adopted the strategies of 'visibility of exemplary practices', which would ensure the dissemination and impregnation of the good teaching model. For the author, numerous devices for the propagation and implementation of 'good molds' were adopted, always with the intention of manufacturing new classroom practices, which would be molded under the supposed precepts of 'modern pedagogy'. Still, for Carvalho, among the teacher training strategies were those of practical demonstrations of the 'art of teaching', displayed in model schools and in the printed dissemination of models or lesson plans in books and journals aimed at teachers (Carvalho, 2006).

According to Carvalho, the “[...] success of the policy of institutionalizing the republican school was, from 1911, largely dependent on what Hilsdorf defined as the traditional capillary system of teaching organization21” (Carvalho, 2006, p. 19 ). The knowledge and practices cultivated in the normal secondary schools were disseminated to the normal primary and complementary schools and, from these, to the model schools, school groups and isolated schools strategically spread in the capital and inland, forming a complex network for the implementation of the model of modern pedagogy (Hilsdorf, 1998). “The capillarity of this school organization system was undoubtedly reinforced by the numerous editorial initiatives to spread knowledge and pedagogical models that these professionals took, by editing magazines and publishing books and articles22” (Carvalho & Toledo, 2021).

It is with the system engendered by the institutions and by the printed matter that, since the first generations of graduates of the Escola Normal Paulista, the mystique of a mission is built: the craft corporation should work in unison and in tune with the transmission of the knowledge and practices referred to to the precepts of 'modern pedagogy' as it was understood (Carvalho, Barreira, & Nery, 2010). The new craft, which was born with the institutionalization of the credentials of the normal school, should impose its representations on good teaching, drawing the distinction between those who possessed technical and efficient knowledge and those schoolmasters who still practiced their profession without having passed formally by this institution (Carvalho & Toledo, 2021).

The mission of transmitting the knowledge required by the civilization in process in Brazil, as well as the effectiveness of practices, always referred to as 'modern pedagogy', constituted the borders of the territory of the imagined community of the new primary teachers. In this sense, well-executed models would separate the good from the bad professionals. These models, in addition to the jargon of the new profession, circulated through specialized journals produced by and for the corporation.

According to Carvalho, the model invented by these forms can be called a 'utensil box' (Carvalho, 2001, 2006). Two magazines are directly debited from the editorial formula of the 'utensil box', as they invented the tradition of the reading model of the São Paulo community of teachers: A Eschola Publica (1893-1897), which was an initiative of teachers from the model school; and Revista do Ensino, organ of the 'Beneficent Association of Public Teachers of the State', (1902-1918).

In the material configuration of these forms are the relationship with the “[...] culturally rooted rules that made up the belief of São Paulo republicans in the renewing impact of what was understood and proposed as modern pedagogy [...]23”; and materiality, which was composed of a whole “[...] repertoire of knowledge that is ordered and arranged as school organization tools in ways compatible with this pedagogy24” (Carvalho, 2001, p. 144). According to Carvalho, they are printed on the pages of these periodicals:

[...] the belief in the incontestable effectiveness of intuitive teaching processes; conceptions about infantile nature formulated within the framework of a psychology of mental faculties; the wager on modern pedagogy as a corpus of knowledge and methodological instruments able to make the school of the masses possible, organizing simultaneous teaching in large classes25 (Carvalho, 2001, p.146).

As has long been known, the autonomy of the teaching profession is also due to the independence that its subjects acquire in relation to the State (Nóvoa, 1991 apud Boto 2018; Catani, 2000). For this reason, its spokespersons will be endorsers (or critics) of the educational policies of which they are contemporary, criticizing the pace and effectiveness of the processes of dissemination of education and government action. In this sense, they produce readings about the present-past of the republic, establishing the horizon of expectations for the success of the profession of teachers, which is inscribed, in this case, in the very success of the civilizing process of the nation. The editors of the Revista de Ensino see themselves as heirs of the authors of Eschola Pública (1893 and 1897), 'the 1st journal for teachers trained in the trade', as agents of the Caetano de Campos reform and as founders of a new era in the instruction of the people of São Paulo (Catani, 2003). Likewise, the 'Associação Beneficente do Professorado' proposed to inherit and continue the traditions invented by that generation.

Therefore, they would be authorized to denounce the serious deficiency in the training of teachers who graduated from complementary schools (Sousa, 1998), which multiplied with the shortage of normal schools in the State. These poorly trained teachers took over the classroom without the slightest training in the knowledge and practices of exercising their trade. For the print editors, magazines proved to be important tools to remedy the deficiencies of new professionals, offering ready-made classes for these new teachers (Catani, 2003); but also as guardians of the tradition of this imagined community.

The Revista de Ensino also denounced the lack of rewards for such an arduous and difficult profession, seeking to enhance the status of the profession in São Paulo society (Catani, 2003). State policies erred in the lack of investment in the trade. The comparison between the 'golden period' and the present situation of the editors of the Revista de Ensino (1903-1918) authorized the denunciations of lack of funds, poor teacher training, the slow pace of implementation of the model graduate school and the lack of vision of politicians, among other arguments, allowing neophytes to enter schools, making them ineffective and disrupting the pace of civilization development (Catani, 2000).

In the early 1920s, criticism of political investments in public education in São Paulo intensified: the school's effectiveness in teaching children of school age to read and write on a large scale (method crisis); the speed of expansion of the school network (reach of classrooms and well-trained teachers); and political effectiveness (engendering order and discipline, nationalizing rebellious working populations) (Carvalho, 2003a).

In 1914, the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo, in a scathing critique of the Rodrigues Alves government, published an Inquiry on the São Paulo school, in which inspectors and other authorities discussed the state's educational crisis. The dissonant voice of d’O Estado was supported by the movement in favor of literacy, promoted by the Nationalist League of São Paulo (Medeiros, 2005). Still, impacted by the workers' strikes of 1917-18, the São Paulo elites began to question the rhythm and contours of the schools inherited from the golden period. With the inauguration of Washington Luís (1920-24), Sampaio Dória was called to solve the problems of the São Paulo school. Carvalho summarizes the defining milestones of the 1920 Reform:

Raising illiteracy to the status of a 'national issue par excellence' and, therefore, prioritizing the extension of the school to marginalized populations, the Reform capitalized on what, in the experience of the pedagogue, Sampaio Dória understood to be the basis of all learning, risking a pedagogical response to a political challenge. Convinced of the method of analytical intuition, he combined with this formula the objectives of moralizing and invigorating the race of the Nationalist League of São Paulo26 (Carvalho, 2003a, p. 230).

However, the new configuration of the literacy school - two compulsory and two optional years - triggered strong resistance, especially from 'education specialists', who presented technical arguments against the structure of the Reform. Sampaio Dória remained at the head of Public Instruction between April 1920 and May 1921, being replaced by his assistant, Guilherme Kuhlmann. The reform was criticized and denounced by several flanks, which legitimized its deconfiguration.

Carlos de Campos, elected in 1924 as governor of São Paulo, presented himself as the person who could restore the traditions of the São Paulo school that had been disrupted by Washington Luís/Sampaio Dória. In this direction, the conflicts between the educators are piqued even more. Voss takes over the Directorate of Public Instruction proposing a new reform, of which RE is the spokesperson.

The criticism of Dória's 'literacy school' indicates a new configuration of theoretical positions in the educational field with regard to the meanings of 'active pedagogy' and, consequently, to the very meaning of the 'glorious São Paulo school', hitherto considered modern and modeling (Carvalho, 2003a). The convictions of the imagined community of educators from São Paulo are beginning to be questioned, thanks to the international debate on new pedagogies/theories of child psychology and new actors. But also because of the clear expansion of the notion of education towards secondary school teachers.

This debate focuses on the meanings of the lesson models of the art of teaching well and its precepts (the psychology of mental faculties), as well as on the effectiveness of the way in which this knowledge was being presented to teachers, whether in normal schools or in specialized periodicals (Carvalho, 2000). The debate was presented to readers through the pages of the mainstream press, through vehicles such as the newspapers Correio da Manhã and O Estado de S. Paulo. Thus, it took shape in the new association founded by old and new names in the educational field, the Education Society of São Paulo (1922-1931) (Nery, 2009).

If the RE was the result of the new Government's immediate positioning in relation to the glorious past of the São Paulo school and its tradition, it was also an intervention strategy to foster new meanings of the alliance between hygiene and the school. So much so that Campos enacted the reform of the Instruction on July 11, 1925, the Pedro Voss Reform, and the following month, enacted the reform of the Sanitary Code, the Paula Souza Reform. In this direction, as Nery (1993) suggests, the magazine itself had aspirations for renewal, since it converged with the renewal of themes and issues that shook the educational field, such as 'hygiene' and its civilizing effects.

With the analysis of the materiality of the magazine, it is possible to perceive that the new generation of educators invested in dissent and attributed the image of 'enemies of politics' to the generation of Pedro Voss, because it represented the 'old education'. The 'old' and the 'new' became the motto of the dispute between those considered heirs of the 'old model' of the São Paulo school (Pedro Voss, João Toledo, Guilherme Kuhlmann, among others) and the 'renovators' of education (Lourenço Filho, Fernando de Azevedo, Almeida Júnior, among others), allied to New School principles. In this binomial that would take place throughout the 1920s, educators critical of the 'model of lessons on things' of 'modern pedagogy' attributed to the Carlos de Campos government the defense of 'educational conservatism', which, in turn, was a sign of the 'rotten oligarchic republic'. The past is reassessed by the new generation based on the idea of overcoming it. Tradition takes on negative contours and signals the republican mismatch.

RE in its materiality

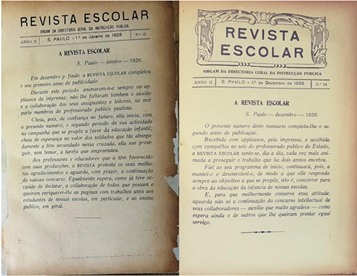

RE had an ephemeral life. The publication began in January 1925 and edited the last issue in September 1927, totaling 33 copies of monthly periodicity. Printing was done by the Siqueira typography, a commercial establishment that provided services to the state government, such as the editing, for example, of the Teaching Annuaries of the State of São Paulo (Razzini, 2006) and school books.

Unlike the journals A Escola Publica, Revista de Ensino27 and the Revista Educação, (from the Sociedade de Educação), which received subsidies from the government, the RE was formalized as the spokesperson of the Board of Directors and became an expense item in the São Paulo budget, guaranteed by Law 2182-C of December 29, 192628. Financing the journal avoided certain publishing complications, as happened in the first half of 1925, when the State Court of Auditors twice denied the credit in the amount of 3:500$000 for RE, but also indicated its importance as a strategy for Pedro Voss to disseminate the ideas proposed by his administration29.

In any case, public investment guaranteed the regularity of the publication as well as its material form. In addition to the contact that teachers in the State of São Paulo had with RE through the donations that the Directoria made to school libraries, they could acquire the new periodical through subscriptions deducted directly from their salaries. These subscriptions could be annual or monthly, with values of 20$000 réis and 10$000 réis. The issues could also be purchased separately (2$000 réis), as shown on this second cover (figure 1).

In the RE subscription form, a document that called on teachers to become subscribers to the journal, it was highlighted that the editorial line favored the collaboration of active teachers: a teacher's magazine designed for teachers. The first editorial described the journal’s content: “It awaits, therefore, with pleasure, collaborations of a didactic nature, pedagogical information, instructions, clarification, in short, any and all work that harmonizes with its nature and purposes30” (Revista Escolar, 1925a, p. 1). To this end, the articles were signed by professors in activity, but the Revista also featured renowned 'collaborations' and authorities of the time, such as general inspectors, national and foreign thinkers, as well as medical authorities. In addition, the journal published official documents (Silva, 2019)31.

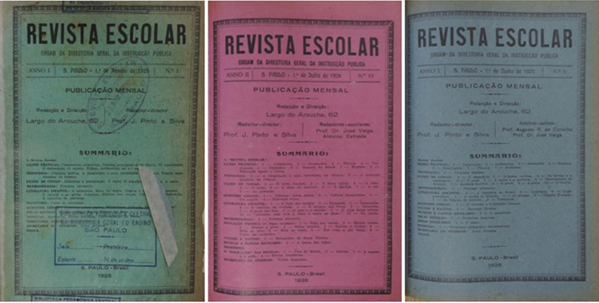

From the beginning of the publication until the end, in September 1927, RE tried to keep the same sections, going through only minor typographic changes after official public investments, such as the layout of the letters, frames to highlight the name and drawings in the subtitles of the sections. These alterations gave it a more sophisticated appearance (Figure 2). The permanent sections were ‘Lições de Coisas’, ‘Lições Praticas, Literatura Infantil’ and 'Questões Geraes', which were present in all issues consulted, as well as the sections ‘Pedologia, Methodologia, Vultos e Fatos, Noticias, Escotismo, Secretaria do Interior, Cantos Escolares, Nos Arraes do Ensino, Educação Physica, Livros e Revista etc.’ and ‘O Folk-lore nas escolas’; the sections ‘Pelas Escolas, Diretoria Geral, Jogos Escolares, Página da Criança, Instrução Publica, O ensino em São Paulo, Resenha Pedagógica e Trabalhos Manuais’ were not always published (Silva, 2020).

Source: Revista Escolar (1926c, p. 2, 1926d, p. 2)

Figure 2 Title page and editorials of two issues of Revista Escolar

In the December 1925 editorial (Revista Escolar, 1925f), the editors hint at a representation of the target reader, which reinforces and, in part, justifies the reading model adopted by the journal:

In its LESSONS ON THINGS and PRACTICAL LESSONS it does not feed, as many have seemed, the desire to force the teacher to abdicate his teaching processes, becoming a mere repeater. Nor would that be conceivable, since, given that even if these lessons constitute sublimated models of perfection, they would still not escape the inherent subjectivity of each educator - subjectivity to which they must fatally be subordinated, suffering, as a consequence, changes in their form and structure.

But, then, why register them on the pages of the REVISTA

‘To, solely and exclusively, offer the neophyte in the teaching profession that which the lack of apprenticeship still does not suit him to provide; to make him wake up early in the spirit to that practice that is only acquired after long years of experience'; so that this teacher acquires it, in short, relatively quickly, for his own benefit and, above all, for the benefit of the children entrusted to him32 (emphasis added).

Already in the November 1925 editorial, it is possible to capture the express representation of 'child' that the magazine circulated. In this editorial, the magazine comments on the problems of the cinematograph in school classrooms. In the view of the editors, this means of communication could harm children, because “[...] in the dramatic representations provided by cinematographers to children, what most attracts them, what most excites and excites them are not the bold traits of nobility or virtue, but the impetuous bids of revenge, the gestures of hate and the like, facts of life33” (Revista Escola, 1925b, p. 2). In this direction, RE understands the child as a being who cannot distinguish what is good from what is bad, the virtuous from the vice. That is, the child is a being who needs someone to guide him within the thriving morality. The magazine thus maintained positions linked to psychology and morality that embodied 'modern pedagogy' and the craft's tradition.

The dominant collaboration of teachers appeared in the sections ‘Lições Praticas’ or ‘Lições de Coisas’ and adopted the formula of lesson models so well known to primary teachers. Still, it is important to emphasize that the section ‘Lições Praticas’, which always occupied the first pages of the magazine, right after the editorial, from August 1926, became the second section, giving way to the section ‘Questões Geraes’; while ‘Lições de Coisas’, another section of lesson plans, started to appear towards the end of the magazine, inviting the reader to leaf through a good part of the magazine.

Regarding the authorship of the published texts and classes, RE presented only a few names, probably names of people who enjoyed a certain prestige or recognition in the educational field, which expressed the idea of authority as authorship (Foucault, 1992). There were 4 (four) authors who had great prominence, or rather, a routine circulation in the magazine's issues: the psychologist Frederic Queyrat and the doctor Henri Bouquet (interspersing in the Pedology section), both of French nationality; and pedagogues Arnold Tompinks and Francis Parker (signing Methodology and Lecture on Teaching respectively), both of American nationality. In addition to them, the Revista sporadically published texts by personalities such as Monteiro Lobato, Cecília Meireles, Decroly, Tolstoi, Fernando Pessoa, among others.

In addition to these authors, RE circulated texts without authorship, which mostly made up the sections ‘Lições de Coisas’ and ‘Práticas’. These texts were probably the contributions of professors included in the imagined community established by the journal itself and appeared in response to requests for collaboration from subscribers. As there is no information about these texts, it is not possible to identify who they are and where they came from.

The circulation of texts dealing with psychology, medicine and education placed the magazine at an important level in the educational scenario, as it showed subscribers how much the magazine was dialoguing with current discussions in the field of education, especially in the medical field, given the great discoveries what psychology and medicine were doing about the child at that moment and the partnerships that education established with health: teachers and the São Paulo Institute of Hygiene; Reform by Pedro Voss and Reform by Paula Souza.

Fonte: Revista Escolar (1925a, 1926f, 1925c)

Figura 3 Capa da Revista Escolar (Revista Escolar, 1925-1927)

With each issue, the cover and the fourth cover of the journal were presented in a different color (figure 3). There were no advertisements34, on RE's pages, which was common in other state-subsidized magazines. The journal also contained photographs: in the 33 copies, 87 photos appear, about 3 photos per issue. The selection of images had a particular and intentional meaning on the part of the editors. The ‘Vultos e Fatos’ section, present in 31 of the 33 copies, edited 24 images/photos of Brazilian personalities. This device made clear reference to the 'Pantheon Escolar' section of the aforementioned journal A Escola Publica (1893 -1897), reaffirming the heritage of São Paulo tradition contained in the policies of Pedro Voss, who was also part of the editorial committee of the Escola Publica (Catani, 2003). According to Catani (2003), A Escola Publica brought in its pages a tribute to personalities that the journal considered admirable and worthy of imitation by teachers and students, which also occurred in RE (Nery, 2009).35

RE also circulated numerous photos of different external and internal school spaces, emphasizing the 'monumentality of the São Paulo school'. Gym classes, physical education, scouting, reading in libraries, among others, symbolized the activity of students, 'the eloquent order and discipline', inherited from the Caetano de Campos Reform. Therefore, these images, as well as the discourse in favor of the São Paulo educational model, sought to reinforce the republican values present in the Carlos de Campos government. At this point, it is important to point out that RE seeks to eliminate the problems arising from the lack of State resources, pointed out by critics of educational policies: it elevates the golden times and tradition, reinforcing the continuities of the inaugural times of the teaching profession, established by the Republic.

As Nery (1993) points out, the ‘Lições de Coisas’ and ‘Lições Praticas’, reminiscent of the heyday of the Republic, were central to the journal and were published in its 33 issues. It is precisely this formula that remains under the control of the group that criticized the older generation. For these intellectuals, it was important to offer professors philosophical discussions and reflections and not a collection of ready-made lessons. On this, Lourenço Filho expressed himself in the inquiry organized by Fernando de Azevedo on June 23, 1926, in the pages of O Estado de S. Paulo:

As for technical assistance, I warmly welcome the idea of the measures that the current administration has taken in this regard, specialized inspectors and a magazine for teachers. If I praise the idea, I sincerely, and not without sadness, regret its execution. RE seems like a deliberate joke or a work of sabotage36 (Lourenço Filho, 1926).

As can be seen, the criticism directly affects the RE model and the representation of the reader instituted by it, since, in Lourenço Filho's view, the reader should not be treated as naive or easygoing on the subject. If the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo (OESP) was the space for criticism against the thinking of the Directorate of Public Instruction37, Voss used RE itself as a spokesman for the positions of his government. Soon after the publication of the Inquérito sobre a Instrução Pública, in June 1926, the August editorial of RE (Revista Escolar, 1926a, p. 1), explained to its readers:

Whoever examines the current reform of public instruction among us, studying it in the light of severe but loyal criticism, this meticulous criticism in its analysis, but noble in its constructive spirit, will see that it presided over a high and safe criterion.

To say that this work, rightly entrusted to the General Directorate of Public Instruction, analyzing it in all its details, would be a work of great merit, as it would show not only the zeal with which matters relating to teaching in S. Paulo are treated, as it would demonstrate the importance that this teaching currently represents for the education of children in our schools.

To do so, however, that is, to prove the excellence of the reform in question, it is sufficient to simply examine certain matters of the programs in force, which have undergone modifications tending to their good educational purpose38 [...]

In that same issue, in the 'Public Instruction'39section, the magazine publishes a message from Governor Carlos de Campos himself, presenting a series of data that would show how Azevedo's analyzes, in the Inquiry, were mistaken and uninformed. According to Campos, “The last reform of the Public Instruction [Voss reform] gave it a new look, without taking away the essence that characterized it since the first republican governments, which always placed it in a position of prominence and importance. way to satisfy the needs of the State40” (Revista Escolar, 1926a, p. 56).

The governor also presented numerical data that demonstrated the importance of the Voss reform for the organization of schools. According to him, the reform allowed “[...] the government to accompany the march of the school units distributed throughout the state and still know the regional needs, for a better location, suppressing the unnecessary ones or creating new sources of teaching, depending on the development of the population centers41” (Revista Escolar, 1926a, p. 57). This speech by the governor not only praises the reform and Voss's stance, but also combats the criticism it had been receiving.

Campos' text expressed the governor's position on the São Paulo educational model, given that Carlos de Campos was the son of Bernardino de Campos, one of the contributors to the legacy of republican education (Vidal, Miguel, & Araujo, 2011). This text also implied the relationship of closeness and trust between Voss and Campos, which perhaps explained Voss' entry and exit from office, which was always linked to Campos' entry and exit from the state government.

The fact is that every criticism published by Azevedo's group, whether in the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo, or in another publication, as is the case of the newspaper Diario Nacional on October 18, 1927, which enthusiastically published the end of Revista Escola, supporters of Voss made the counter-argument: sometimes with milder responses, sometimes with a lot of force, as can be seen in the excerpt published in the magazine's editorial in February 1926 (Revista Escolar, 1926b, p. 1).

There are some zoilos out there slandering this MAGAZINE, and it seems to us that they do so, because they have not yet been able to give them a purely guiding purpose in the part relating to their practical lessons on various subjects of our school programs. However, it must be confessed, if the didactic strabismus of similar critics does not allow them to see things through their proper meaning, it has not lost the degree of acuity sufficient to compete with the microscope: like this, their critical eye discovers molecules, particles, atoms [...] but, unfortunately, it does not unite the whole, it does not observe the harmony of the whole.

Drumming some of their aversion for the said lessons, others trumpeting their contempt for them, they all go, solely and in an impulsive, morbid obsession, proclaiming the verdict found in the cenacle that they reached there in the Himalayas of their wisdom42.

Regarding the criticisms of the perpetuation of teaching based on good models, where the sections ‘Lições de Coisa’ and ‘Lições Praticas’, for example, are placed, RE has countered them at various times43 of its existence. In the June 1925 editorial (Revista Escolar, 1925c, p. 1), for example, the editors say that,

This JOURNAL, destined to deal with the general interests of teaching, has been dedicating itself, with particular care, to didactics in terms of its direct application in the primary school environment.

Thus, to her PRACTICAL LESSONS and THINGS LESSONS, she has tried to imprint a truly practical character, in order to produce the maximum benefit and utility for children. However, it is not always necessary to recognize it, such lessons have reached the desired scope; they have not always been developed according to all the requirements that must be inherent to them. There are so many and so delicate conditions of a didactic nature to which they need to be subordinated; there are so many observations of a pedagogical nature that fall within them, that something must necessarily escape the most astute mind in terms of teaching44.

In the description of the magazine's material formula, it is indicated how the 'utensil box' was adopted by its editors, maintaining the tradition of the current reading and training model in publications of this genre, in addition to a whole conception of pedagogy that resumed the architecture of 'modern pedagogy'. However, there are discursive displacements adopted by the press that accompanied the renewal of the educational debate, especially with regard to the transformations operated by the medical and hygiene sciences.

In this sense, the grandiose speech of the school is consistent with the hygienic precepts defended by the Institute of Hygiene of São Paulo. These displacements can be noticed, for example, in the way public schools are photographed: always shown by the editor in their exuberance and grandeur, but also as exemplary spaces of what was prescribed in the new Sanitary Code (1924). If these framings of the colossal position of the buildings corroborate the 'pedagogy of the art of teaching' and the 'priority of visibility' - a sine qua non of the teaching-learning relationship - they also became models of the hygienic order linked to educational policies. The following photos exemplify this a bit (figures 4, 5 and 6):

Displacements and points of convergence

With Voss at the head of the Board, it can be said that RE gave relevance to issues related to body care. This can be seen from the mapping of the articles published during the years of its existence. When considering these 'precautions', it is possible to affirm that the journal was a great incentive for the dissemination of hygiene, discussing, for example, the problems of alcoholism, the risks of eating with dirty hands, the importance of neat clothing, care for nails and hair, etc.

The journal saw the condition of the people as a key problem and endorsed the representation, announced at a conference offered at an event by the Liga Nacionalista, of the promoter of hygiene reform, Paula Souza, on the subject, namely: it was necessary to raise it to the condition of importance in the educational tonic. This position of Paula Souza regarding dealing with health issues with education was echoed in the magazine's editorial board, corroborating the construction of a hygienic discursive field, because, as Marta Carvalho points out, “[...] , in the [19]20s, the conviction that health policy measures would be ineffective if they did not cover the introjection, in social subjects, of hygienic habits, through education45” (Carvalho, 2009, p. 305).

This educational discourse focused on overcoming the miasmatic theory in terms of the bacteriological theory, since it would consecrate the studies that proved that the disease was not generated by miasms, but by viruses, fungi and bacteria. This paradigm shift led many intellectuals to take ownership of this new idea, as did Monteiro Lobato, with his character Jeca-Tatu, who ceased to be the sign of the indolence of the race to be the victim, that is, the sick man abandoned by the State.

If, in the 1910s, it was already possible to see the concern with the theme of hygiene, as occurred with the first Sanitary Code (1911)46 and with the course promoted by Oscar Thompson to school directors, the new approach of the Paula Reform Souza gives sanitary and hygiene practices a whole new framework of meanings. Thus, the hygienic discussion, apparently inherited from the glorious times of the São Paulo school, especially with regard to the insistence on the habits of students, shifted towards the new scientific theories that formed the basis of Paula Souza's reform. It is the content of the rupture of the new theory of hygiene that the magazine circulated in the 1920s.

In Souza's view, hygiene at school continued to be responsible for inculcating healthy habits in children, keeping them away from society's vices, so it was necessary to clarify to teachers how diseases were perpetuated and how transmission took place in the daily life of city life. and rural. Hence the important partnership with RE, especially in the commitment to present the theme recurrently in the sections ‘Lições Praticas’ and ‘Lições de Coisas’.

These sections took body care from an immediate perspective, investing in practical prescriptions for taking care of contamination and disease, such as care for clothes, nails, housekeeping, among others. Furthermore, they prescribed prevention in a long-term perspective, that is, the importance of eating well, avoiding alcohol and tobacco, practicing physical activity, avoiding fat and being overweight. For example, in the section ‘Lições Praticas’ (Revista Escolar, 1926c), the central motto is the preservation of students from the transmitters of the most common diseases in cities:

Student. - A doctor from the health service went to the house yesterday to see if there was water in the tank, or stagnant water anywhere. Why would it be?

Teacher. - Because of mosquitoes, mosquitoes [...]

Professor, - The mosquito, like the fly, is first of all an egg; later, larva; then cocoon, and finally, perfect insect... Kerozene spread over the water destroys the eggs. The larvae and cocoons, not being able to get air through the layer of oil, die too. Adults cannot approach the surface of the water to lay more eggs, and if they insist on getting there, they die too.

Student. “They annoy us by singing and biting, but they're not that bad, are they?

Teacher. - Why not! Mosquitoes, like flies, transmit disease germs [...]

Professor, - There were places where life was almost impossible, due to the large number of mosquitoes and other harmful insects. After Hygiene set to work sanitizing these locations, exterminating the dangerous insects, they became perfectly inhabitable and desirable47.

In this question and answer scheme, located in an apparently commonplace situation, the magazine taught the professor how to teach the new scientific theories about the transmission of diseases, as well as about healthy habits and the order and discipline that should accompany civilization. As can be seen, RE adopts a material form inscribed in the traditions of reading practices that were part of the culture of the community of primary school teachers in São Paulo.

However, its editors produced subtle shifts in content and materials, especially in relation to the new hygienist precepts that emerged in the 1910s and 1920s. In other words, the magazine's editors used the same editorial formulas from the tradition of the São Paulo educational field to introduce the new contents of medical and hygienic sciences. The maintenance of the old editorial formulas, and even of the contents that were related to teaching practices, allowed, on the one hand, the acceptance of the public for which the printed matter was intended, reaffirming the representations of the functions of the printed matter in the formative process of the profession of teacher; but, on the other hand, it opened up a flank for criticism from the new generation of educators, who, despite agreeing with hygienist approaches, were opposed to 'modern pedagogy' and ways of teaching how to teach from the logic of lesson models.

This ambiguity between tradition and renewal in the field of education was erased by the memory of Azevedian historiography, which ended up establishing the interpretation that both the Voss Reform and the RE were a setback in the positive process of development of education in São Paulo. This new generation reassessed the past and tradition, insisting on new contours for the knowledge, practices and meanings of the teaching profession, also focusing on the present and past meanings of the imagined community of primary school teachers and constituting a new horizon of expectations for this community.

In this field of dispute, the magazine's actions would be configured either in defense of the criticism received, or in attack against those who took a stand against the traditions of the São Paulo school. However, despite the Manichaeism of the educational debate, some questions instituted the convergences, mixing the representations of the different groups: if there was clear disagreement about the teaching methods derived from modern pedagogy and child psychology and, for that very reason, about the representations of reading practices of the target teachers; there was a consensus on the use of printed matter as a unique strategy for disseminating the alliance between hygiene and education: the school should be the primary place for inculcating the habits of order and hygiene. In this way, the magazine's critics pointed to what they thought was a problem, especially the educational model inherited from the beginning of the Republic, but did not attack the magazine's position in relation to hygiene or the partnership with Paula Souza, director of the Sanitary Service, or with the São Paulo Institute of Hygiene.

The hypothesis of this investigation to explain the limited criticism of the educational methods that the group of intellectuals 'born with the Republic' addressed to the magazine and to Pedro Voss's reform is that the articulation between health and education was not in question, considering the importance that hygiene, in the 1920s, starts to have with the demonstration of the bacteriological theory. Furthermore, it is important to remember that many of those who were criticizing Pedro Voss' position were physicians, as is the case of some contributors to the 1926 Survey. Thus, the importance of hygiene for the educational issue was a consensus, without a shadow of doubt; the educational methods, the representations of the child and even the teacher were in intense dispute.

Final remarks

With Pedro Voss at the head of the General Directorate of Public Instruction, at the invitation of Carlos de Campo, RE was born. As Voss was a staunch republican, he made the RE pages a place of defense of the São Paulo educational model marked by the legacy of the Caetano de Campos/Gabriel Prestes reforms. This heritage materializes in the sections ‘Lições de Coisas’ and ‘Lições Praticas’. But it also materializes in the primacy of visibility of the schools printed in the photographs of the front covers and practical classes.

It was this reading and training model that intellectually nourished the new teachers in classrooms scattered across the state (and perhaps the country), expanding the so-called São Paulo educational model. This printed formula representing the recipient's reading practices justified the way the journal presented itself, that is, a menu of classes, leaving 'philosophical' discussions in the background.

This defense of the republican school and its pedagogical precepts (active school according to the precepts of modern pedagogy), especially in the way the journal presented itself to the reading public, opened space for the opposition group to direct many of its criticisms of the Revista. For these intellectuals, who were part of the 1926 Survey, the way in which the Revista constructed its proposals did not dialogue with the real needs of (more modern) teachers, as it advocated a more philosophical and critical teaching profession. Therefore, the way in which the Revista presented its content, in the format of 'questions' and 'answers', would lead the opposition group, particularly the figure of Lourenço Filho, to say that the professorship of São Paulo did not lack a 'purposeful joke or work of sabotage'.

Another point that this study sought to focus on was the relationship between politics and education. In this sense, it is believed that the attacks deferred to the educational model of São Paulo, which appear in the pages of the journal in the form of a response, also had the government of Carlos de Campos as their target, since this would be, in all its dimensions, the result of the oligarchic and worm-eaten republic.

Although a historiography closer to the studies of Fernando de Azevedo (Antunha, 1975; Nagle, 2009) has been concerned with locating these characters as antagonistic, this article sought to show that there was a certain consensus among these intellectuals with regard to the social function of the school, that is, disciplining, ordering and sanitizing childhood in São Paulo. This confluence of ideas, to a certain extent, allows us to say that the relationships between these intellectuals did not take place in such antagonistic ways as the Azevedian matrix suggested.

In this way, the hygienic discourse, which in the 1920s would become an important concern in the São Paulo society, largely due to the new bases of science and the high number of deaths caused by the Spanish flu of 1918, would be a point of convergence between these thinkers; although the opposition group, in the Inquérito de 1926, put the Reform of Pedro Voss in the spotlight, he defended the Reform of Paula Souza, approved exactly one month later, by the same government. What was in dispute were the representations about literacy models, about the psychology of children/students, about teachers' practices and, specifically, about their reading and training practices. On the other hand, health was already a field of consensus.

REFERENCES

Anderson, B. (2008). Comunidades imaginadas: reflexões sobre a origem e a difusão do nacionalismo. São Paulo, SP: Companhia das Letras. [ Links ]

Antunha, H. C. G. (1975). A Instrução Pública no Estado de São Paulo: a reforma de 1920. São Paulo, SP: Universidade de São Paulo. Faculdade de Educação. [ Links ]

Azevedo, F. (1937) A educação pública em São Paulo, problemas e discussões: inquérito para O Estado de S. Paulo em 1926. São Paulo, SP: Companhia Editora Nacional. [ Links ]

Bontempi Jr., B. (2007). O Inquérito sobre a situação do ensino primário em São Paulo e suas necessidades (O Estado de São Paulo, 1914): fonte para o estudo do imaginário republicano. In Anais do 24° Simpósio Nacional de História - ANPUH (Vol. 1. p. 1-9). São Leopoldo, RS. [ Links ]

Boto, C. (2018). António Nóvoa: uma vida para a educação. Educação e Pesquisa, 44, 1-15. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. (2003a). Reformas da Instrução Pública. In E. Lopes, L. M. Faria Filho, & C. G. Veiga (Orgs.), 500 anos de Educação no Brasil (p. 225-251). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M., Barreira, L. C., & Nery, A. C. B. (2010). “Antonio Firmino de Proença na imprensa de educação e ensino”. In: M. P. G. Razzini (Org.), Antonio Firmino de Proença: professor, formador, autor (p. ?-?). São Paulo, SP: Porto de Ideias. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M., & Toledo, M. R. (2021). Fontes para estudo da cultura escolar: o caso da imprensa periódica educacional paulista e suas estratégias textuais de ordenamento da profissão docente (1823-1927). Revista de Fontes, 8(15). [ Links ]

Carvalho, M., & Toledo, M. R. (2007). Os sentidos da forma: análise material das coleções de Lourenço Filho e Fernando de Azevedo. In M. A. Taborda de Oliveira (Org.), Cinco estudos em história e historiografia da educação (v. 1, p. 89-110). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica . [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (2001). A caixa de utensílios, o tratado e a biblioteca: pedagogia e práticas de leitura de professores. In: D. G. Vidal, & M. L. Hilsdorf (Orgs.), Tópicos de história da educação (p. 137-167). São Paulo: Edusp. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (2003b). A escola e a república e outros ensaios. Bragança Paulista, SP: Ed. da Universidade São Francisco. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (2006). “Livros e revistas para professores: configuração material do Impresso e circulação internacional de modelos pedagógicos”. In M. M. C. Carvalho, & J. Pintassilgo (Orgs.), História da escola em Portugal e no Brasil: circulação e apropriação de modelos culturais (p. 141-175). Lisboa, PT: Edições Colibri. [ Links ]

Carvalho, M. M. C. (2000). Modernidade pedagógica e modelos de formação docente. São Paulo em Perspectiva, 14, 111-120. [ Links ]

Catani, D. B. (2003). Educadores à meia luz: um estudo sobre a Revista do Ensino da Associação Beneficiente do Professorado Público de São Paulo (1902-1918). Bragança Paulista, SP: EDUSF. [ Links ]

Catani, D. B. (2000). Estudos de história da profissão docente. In E. Lopes, L. M. Faria Filho, & C. G. Veiga (Orgs.), 500 anos de Educação no Brasil (p. 585-599). Belo Horizonte, MG: Autêntica . [ Links ]

Cordova, T. (2016). Redações, cartas e composições livres: o caderno escolar como objeto da cultura material da escola (Lages/SC - 1935). História da Educação, 20, 209-226. [ Links ]

Cruz, H. F. (2000). São Paulo em papel e tinta: periodismo e vida urbana (1890-1915). São Paulo, SP: Educ/FAPESP. [ Links ]

De Certeau, M. (1998). A invenção do cotidiano (Vol. 1). Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 3.876, de 11 de julho de 1925. (1925, 12 de julho). Reorganiza o serviço sanitário e repartições dependentes. Diário Oficial. p. 4929. Recuperado de:https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1925/decreto-3876-11.07.1925.html [ Links ]

Decreto nº 3.858, de 11 de junho de 1925. (1925, 23 de junho). Reforma a Instrução Pública. Diário Oficial . p. 4569. Recuperado de:https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1925/decreto-3858-11.06.1925.html#:~:text=%2D%20As%20f%C3%A9rias%20de%20Inverno%20ser%C3%A3o,os%20estabelecimentos%20de%20ensino%20primario. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 2.141, de 14 de novembro de 1911. (1911, 25 de novembro). Reorganiza o serviço sanitário do Estado. Diário Oficial . p. 4539. Recuperado de: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1911/decreto-2141-14.11.1911.html. [ Links ]

Decreto nº 2.918, de 9 abril de 1918. (1918, 10 de abril). Dá execução ao Código Sanitário do Estado de São Paulo. Diário Oficial . p. 2169. Recuperado de: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/1918/decreto-2918-09.04.1918.html. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1992). O que é o autor?Lisboa, PT: Vegas/Passagens. [ Links ]

Hansen, J. A. (2019). O que é um livro? São Paulo, SP: Ateliê Editorial. [ Links ]

Hilsdorf, M. L. S. (1998). “Lourenço Filho em Piracicaba”. In C. P. Sousa (Org.), História da educação. processos, práticas, saberes (p. 95-113). São Paulo, SP: Escrituras, [ Links ]

Lourenço Filho, M. B. (1926, 23 de junho). A Instrucção Publica em São Paulo: ensino primário e normal, ainda a resposta do Sr. Lourenço Filho. O Estado de S. Paulo. p. 4. [ Links ]

Medeiros, V. A. (2005). Antonio de Sampaio Dória e a modernização do ensino em São Paulo nas primeiras décadas do século XX (Tese de Doutorado). Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Nagle, J. (2009). Educação e sociedade na Primeira República. São Paulo, SP: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo. [ Links ]

Nery, A. C. B. (1993). A revista escolar e o Movimento de Renovação em São Paulo (Dissertação de Mestrado). UFSCar, São Carlos. [ Links ]

Nery, A. C. B. (2009). A sociedade de educação de São Paulo: embates no campo educacional (1922-1931). São Paulo, SP: Ed. Unesp. [ Links ]

Nóvoa, A. (Org.). (1991). Profissão professor. Porto, PT: Porto Editora. [ Links ]

Razzini, M. P. G. (2006). A produção didática da Tipografia Siqueira: caminhos de pesquisa. In Anais do 29º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação (p. 1-11). São Paulo, SP. [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública. (1925a, janeiro). I(1). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1925b, novembro). I(11). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1925c, junho). I(6). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1925d, março). I(3). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1925e, abril). I(4). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1925f, dezembro). I(12). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926a, agosto). II(20). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926b, fevereiro). II(14). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926c, janeiro). II(13). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926d, dezembro). II(24). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926e, novembro). II(23). [ Links ]

Revista Escolar - Orgam da Directoria Geral da Instrucção Pública . (1926f, julho). II(19). [ Links ]

Silva, R. P. A. (2019). A higiene na cidade de São Paulo: duas faces de uma mesma moeda. In E. C. Ricardo, E. M. Pataca, F. Ginzel, H. H. C. Onisaki, K. Tomizaki, L. J. Pino,... V. A. A. Araújo (Orgs.), Pesquisa em educação: diversidade e desafios (22a ed., v. 1, p. 210-219). São Paulo, SP: FEUSP. [ Links ]

Silva, R. P. A. (2020). As propostas educacionais de higienização veiculadas pela RE (1925-1927) (Dissertação de mestrado). Unifesp, Guarulhos. [ Links ]

Sousa, C. P. (1998). Fragmentos de histórias de vida e de formação de professoras primárias paulistas: rupturas e acomodações. In C. P. Sousa. (Org.), História da educação: processos, práticas, saberes (1a ed., p. 27-42). São Paulo, SP: Escrituras . [ Links ]

Toledo, M. R. A. (2020). Coleção atualidades pedagógicas: do político ao projeto editorial. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Toledo, M. R. A. (2013). Coleções autorais, traduções e circulação: ensaios sobre geografia cultural da edição (1930 - 1980) (Tese de Livre Docência). Unifesp, São Paulo. [ Links ]

Vidal, D. G., Miguel, M. E. B., & Araujo, J. C. S. (Orgs.). (2011). Reformas educacionais: as manifestações da Escola Nova no Brasil (1920 a 1946). Uberlândia, MG: EDUFU. [ Links ]

Vesentini, P., & Lugli, R. (2009). História da profissão docente no Brasil: representações em disputa. São Paulo, SP: Cortez Editora. [ Links ]

17It is considered that the original spelling is part of the typographic devices of the printed material and, for this reason, the writing of the cited texts will not be updated.

18TN. “[...] associavam o livro/leitura e a escola a atitudes simbólicas e mentais que permitiriam o progresso do país, seja como práticas civilizatórias, seja como práticas disciplinares e de controle cultural” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

19We borrowed Benedict Anderson's expression 'imagined community'. The author focuses on the historical processes of engendering the notions of nation and nationalism that are instituted. For him, the production of periodicals is an important cog in the 'imagination' engine that constitutes a community. The borrowing of the term is justified insofar as the primary school teacher, on the one hand, is represented as one of the institutionalizing agents of the nation and civilization; on the other hand, because the craft is instituted based on the delimitation of specialized knowledge and practices, as well as the territory (identities) of those who are authorized to efficiently teach writing-reading-counting (and the nation); excluding a wide range of other agents who until then were responsible for transmitting this knowledge. Anderson recalls that: “[...] in fact, any community larger than a primordial village of face-to-face contact (and perhaps itself) is imagined. Communities are distinguished not by their falsity/authenticity, but by the style in which they are imagined” (Anderson, 2008, p.33).

20TN. [...] “o impresso funcionará como dispositivo de regulação e adequação do discurso e da prática pedagógica do professorado” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

21TN. “[...] sucesso da política de institucionalização da escola republicana foi, a partir de 1911, largamente dependente do que definiu Hilsdorf como tradicional sistemática capilar da organização do ensino” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

22TN. “A capilaridade desse sistema de organização escolar foi reforçada, sem dúvida, pelas inúmeras iniciativas editoriais de propagação de saberes e modelos pedagógicos que esses profissionais tomaram, editando revistas e publicando livros e artigos” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

23TN. “[...] regras culturalmente enraizadas que compunham a crença dos republicanos paulistas no impacto renovador do que era entendido e proposto como pedagogia moderna [...]” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

24TN. “[...] repertório de saberes que se ordenam e se dispõem como ferramentas de organização da escola em moldes compatíveis com essa pedagogia” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

25TN. “[...] a crença na eficácia inconteste dos processos de ensino intuitivo; concepções acerca da natureza infantil formuladas nos marcos de uma psicologia das faculdades mentais; a aposta na pedagogia moderna como corpus de saberes e de instrumentos metodológicos aptos a viabilizar a escola de massas, organizando o ensino simultâneo em classes numerosas” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

26TN. “Alçando o analfabetismo ao estatuto de ‘questão nacional por excelência’ e, por isso, priorizando a extensão da escola às populações marginalizadas, a Reforma capitalizava o que, na experiência do pedagogo, Sampaio Dória entendia ser a base de toda a aprendizagem, arriscando uma resposta pedagógica a um desafio político. Convencido do método de intuição analítica aliava a essa fórmula os objetivos de moralização e vigorização da raça da Liga Nacionalista de São Paulo” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

27Regarding the Revista de Ensino, the State contributed financially to it, however, there were periods when the contribution ceased, especially when the journal criticized political leaders (see Catani, 2003).

28Law 2.182-C was published by the Secretariat of State for Interior Affairs on January 3, 1927. Retrieved from: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei/1926/lei- 2182C-29.12.1926.html.

30TN. “Ella aguarda, pois, com prazer, collaborações de caracter didatico, informações pedagogicas, instruções, esclarecimento, enfim todo e qualquer trabalho que se harmonize com a sua natureza e os seus fins” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

31Law No. 2095 of December 24, 1925, which approves Decree No. 3858 of June 11, 1925 (Pedro Voss Reform) was published in full in the Revista Escolar of February 1926.

32TN. “Em suas LIÇÕES DE COISAS e LIÇÕES PRATICAS não alimenta, como muitos tem parecido, a velleidade de forçar o professor á abdicação dos seus processos de ensino, tornando-se um méro repetidor. Nem tal seria concebivel, porquanto, dado mesmo que essas lições constituissem modelos sublimados de perfeição, ainda assim não escapariam á subjectividade inherente a cada educador - subjectividade a que ellas fatalmente devem subordinar-se soffrendo, por consequencia, modificações em sua fórma em sua estructura. Mas, então, para que registal-as nas paginas da REVISTA ‘Para, unica e exclusivamente, offerecer ao neophyto no magistério aquillo que a exiguidade de tirocinio ainda não lhe approuve proporcionar; para fazer madrugar-lhe no espirito essa pratica que sómente se adquire após longos annos de experiencia’; para que esse professor a adquira, emfim, com relativa brevidade, em beneficio proprio e, sobretudo, em pról das crianças a elle confiadas (grifo nosso)” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

33TN. “[...] nas representações dramáticas proporcionadas pelos cinematógrafos ás crianças, o que mais as attráe, o que mais as emociona e empolga não são os rasgos arrojados de nobreza ou de virtude, mas os lances impetuosos de vingança, os gestos de ódio e quejandos facto da vida” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

34In March 1925, an invitation was printed in the magazine for advertisers of bookstores, educational establishments, stationery stores, article stores and school furniture. However, advertisements never appeared.

35Regarding the editors of RE, João Pinto e Silva has always been ahead of the jorunal, however, there were times when he shared this task with Augusto R Carvalho, Jose Veiga, Alduino Estrada and Antônio Faria.

36TN. “Quanto à assistência técnica, louvo com o maior entusiasmo a ideia das medidas que a atual administração tomou a respeito, inspetores especializados e uma revista para professores. Se louvo a ideia, lamento, porém, com sinceridade, e não sem tristeza, a sua execução. A RE parece uma pilhéria proposital ou obra de sabotagem (Lourenço Filho, 1926)”. (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese)

37It is worth remembering that the OESP published educational surveys in 1914 and 1926 against the current education model.

38TN. “Quem quer que examine a actual refórma da instrução publica entre nós, estudando-a á luz da crítica severa mas leal, dessa critica meticulosa em sua analyse, porém nobre pelo seu espirito constructor, verá que a ella presidiu um criterio elevado e seguro. Dizer desse trabalho, em boa hora confiado á Directoria Geral da Instrucção Publica, analysal-o em todos os seus detalhes, seria obra de grande mérito, pois evidenciaria não só o zelo com que são tratados os assumptos relativos ao ensino em S. Paulo, como demonstraria a importancia que actualmente este ensino representa para a educação da infancia de nossas escolas. (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese). Para tanto, porém, isto é, para provar a excellencia da reforma em questão, é sufficiente o simples exame de certas materias dos programmas em vigor, as quaes soffreram modificações tendentes á sua boa finalidade educativa [...]” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

39In the whole RE cycle, this section appeared only 4 times, two of them to talk about Decree nº 3.858 (1925) (Pedro Voss Reform).

40TN. “A ultima reforma da Instrucção Publica [reforma Voss] deu-lhe nova feição, sem com tudo, tirar-lhe a essência que a caracteriza desde os primeiros governos republicanos, que sempre a collocaram em situação de destaque e de maneira a satisfazer as necessidades do Estado” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

41TN. “[...] o governo acompanhar a marcha das unidades escolares distribuídas pelo território do estado e ainda saber das necessidades regionaes, para melhor localização, supprimindo as desnecessarias ou creando novas fontes de ensino, consoante o desenvolvimento dos nucleos de população” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

42TN. “Andam por ahi alguns zoilos a malsinar esta REVISTA, e parece-nos que assim procedem, por não terem podido ainda lobrigar-lhes o intuito méramente orientador na parte relativa ás suas lições praticas sobre diversas materias dos nossos programmas escolares. Todavia, força é confessar, si o estrabismo didactico de semelhantes criticomanos não lhes permite enxergar as coisas atraves da sua justa significação, nem por isso perdeu o grau da acuidade sufficiente para concorrer com o microscopio: como este, o seu olho critico descobre moleculas, particulas, átomos […] mas, infelizmente, não reune o todo, não observa a harmonia do conjunto. Tamborilando uns a sua aversão pelas referidas lições, trombeteando outros o seu menosprezo pelas mesmas, vão todos eles, unicamente e numa obcecação impulsiva, morbida, proclamando, o veredicto apurado no cenáculo que alcandoraram lá no Himalaia da sua sapiencia” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

43On the importance of the sections 'Lições de Coisas' and 'Lições Praticas', the magazine wrote in several editorials the need for these sections, especially for new teachers.

44TN. “Esta REVISTA, destinada a tratar dos interesses geraes do ensino, vem se dedicando, com particular cuidado, á didatica quanto á sua applicação directa no meio escolar primario. Assim, ás suas -LIÇÕES PRATICAS e LIÇÕES DE COISAS, ella tem procurado imprimir um caracter verdadeiramente pratico, de molde a produzirem ellas o maximo de proveito e utilidade ás crianças. Nem sempre, porém, cumpre reconhecel-o, taes lições tem attingido o escopo desejado; nem sempre tem sido desenvolvidas consoante todos os requisitos que lhes devem sêr inherentes. São tantas e tão delicadas as condições de ordem didatica a que ellas precisam subordinar-se; são tantas as observações de natureza pedagogica que nellas se enquadram, que, forçosamente, alguma coisa ha de escapar ao mais arguto espirito em materia de ensino”. (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

45TN. “[...] firma-se, nos anos [19]20, a convicção de que medidas de política sanitária seriam ineficazes se não abrangessem a introjeção, nos sujeitos sociais, de hábitos higiênicos, por meio da educação” (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

46 Decree nº 2.141, of November 14, 1911 and later with Decree nº 2.918, of April 9, 1918, which also dealt with hygiene.

47TN. Alumno. - Um medico do serviço sanitário foi, hontem, em casa para vêr si havia agua no tanque, ou agua estagnada em qualquer logar. Por que seria? Professor. - Por causa dos mosquitos, dos pernilongos[...] Professor, - O mosquito, como a mosca é primeiramente ovo; depois, larva; em seguida, casulo, e finalmente, insento perfeito... O kerozene espalhado sobre a agua destróe os óvos. As larvas e os casulos, não podendo obter ar através da camada de óleo, morrem também. Os adultos não podem se approximar da superficie da agua para porem mais óvos, e si por ventura insistirem em ahi chegar morrem tambem. Alumno. - Elles nos aborrecem cantando e mordendo, mas não são assim tão maus, são? Professor. - Como não! O mosquito, como a mosca, é transmissor de germens de moléstias [...] Professor, - Localidades havia onde a vida era quase impossível, devido á grande quantidade de mosquito e outros insectos nocivos. Depois que a Hygiene pôz mãos á obra saneando essas localidades, exterminando os perigosos insectos, ellas se tornaram perfeitamente habitaveis e desejáveis. (freely translated from Brazilian Portuguese).

64Peer review rounds: R1: three invitations; one report received. R2: two invitations; one report received

65How to cite this article: Silva, R. P. A., & Toledo, M. R. A. (2023). Revista Escolar as a space for dispute and legitimization of the discourse: Convergence in the divergence of ideas (1925-1927). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v23.2023.e275

66Funding: RBHE has financial support from the Brazilian Society of History of Education (SBHE) and the Editorial Program (Call No. 12/2022) of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

67Licensing: This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4) license.

Received: September 26, 2022; Accepted: April 25, 2023; Published: June 30, 2023

texto en

texto en