Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de História da Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1519-5902versión On-line ISSN 2238-0094

Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ vol.23 Maringá 2023 Epub 01-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v23.2023.e277

DOSSIER

‘Dear mommy, dear daddy’: the invention of a school practice (1964 - 1980)

1Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Pelotas, RS, Brasil.

The present study aimed to describe and discuss the materiality of a set of 35 cards, which represent a school practice of making cards that allude to commemorative dates such as Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. The study was performed taking into account cards in dialogue with other complementary sources. The materials were produced between the years of 1964 and 1980 in multigrade schools in the rural area of the municipality of Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul. The artifacts were characterized by the cultural history approach and interpreted from the perspective of school material culture. In conclusion, the production of greeting cards is constituted by the school curriculum and consolidated by a practice of invented tradition.

Keywords: history of education; school culture; material culture; educational practice

O objetivo deste artigo é descrever e problematizar a materialidade de um conjunto de 35 cartões, representativos de uma prática escolar de confecção de cartões alusivos às datas comemorativas do Dia das Mães e do Dia dos Pais. O trabalho foi realizado considerando os cartões na interlocução com outras fontes complementares. Os materiais foram produzidos no período entre os anos de 1964 e 1980 em escolas multisseriadas da zona rural do município de Pelotas/RS. Os artefatos foram caracterizados pela abordagem da história cultural e interpretados pela perspectiva da cultura material escolar. Concluiu-se que a produção dos cartões comemorativos é constituída pelo currículo escolar e consolidada por uma prática de tradição inventada.

Palavras-chave: história da educação; cultura escolar; cultura material; prática educativa

El objetivo del artículo es describir y problematizar la materialidad de un conjunto de 35 tarjetas, representativos de una práctica escolar de confección de tarjetas alusivas a las fechas conmemorativas del Día de las Madre y del Día del Padre. El trabajo se llevó a cabo considerando las tarjetas em la interlocución con otras fuentes complementarias. Los materiales se produjeron entre los años 1964 y 1980 en escuelas multigrado de la zona rural del municipio de Pelotas/RS. Los artefactos fueron caracterizados por el abordaje de la historia cultural e interpretados por la perspectiva de la cultura material escolar, y se llegó a la conclusión de que la producción de las tarjetas conmemorativas está constituida por el currículo escolar y consolidada por una práctica de tradición inventada.

Palabras clave: historia de la educación; cultura escolar; cultura material; práctica educativa

Introduction

The consolidation of the fields of school culture and school material culture, linked to the perspective of Cultural History (Chartier, 1988), encompasses changes, challenges, and potentialities, which configured this historiographical turn, in which there is a shift of interest, which passes from the level of educational policies and recognized institutions to cultural and everyday practices, in which objects, their materiality and their uses are taken into account. There is, in this sense, the appreciation of multiple school productions, understanding them as an educational heritage characterized by specific cultural practices and empirical modes of the teacher and student doing present in the school space (Benito, 2010).

The prospect of expanding sources from cultural history (Bencosta, 2007; Felgueiras, 2015) constitutes a potential horizon of investigation, which enables or requires researchers in the area to comprehensively insert documentary sources, precisely because it intends to enter the space of cultural practices that configure the school setting. Such a perspective imposes a conceptual and methodological effort, since not only access to the sources is necessary, but also a creative and differentiated work for their interpretation.

When mentioning the consolidation of the fields of school culture and school material culture - which was demarcated in Brazil, especially from the final years of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century (Bencosta, 2007) -, in no way, this consolidation be understood as a unification of these fields and notions. It is necessary to understand that these are fields demarcated by disputes and tensions, which differ in conceptual and methodological relationships and which can be worked on in a correlated way or analyzed differently.

International authors, such as Benito (2000), Dussel (2014), Frago (2008), and Julia (2001), exemplify these disputes, exposing concepts and problematizing them, in an attempt to explain them and demarcate the spaces for reflection and interlocutions. Therefore, it is necessary to understand that both fields, in different perspectives, emphasize that the production of school culture and school material culture are organized based on the cultural and social relations of the constituting actors, characterizing a comprehensive material production, which allows the exploration of several documentary sources, as well as enabling previously ignored artifacts and materials to integrate investigative scenarios and enhance reflections on the school’s cultures.

Thus, based on this understanding, each researcher who approaches investigations with and about school material culture will be able to contribute, based on their theoretical and methodological approaches, to the expansion and presentation of new documentary sources and exploratory, reflective, and discursive possibilities. In this sense, this study presents a possibility of a documentary source that refers to a school production carried out manually, which consists of cards that allude to the celebrations of Mother’s Day and Father’s Day.

These artifacts, produced by students and teachers at school, carry, in their materiality, an investigative possibility, which brings up aspects of school material culture and which can be explored in line with aspects related to pedagogical discourses, curriculum organization, conceptions of childhood and family standardization, among others. They are representative of a given practice and are saved from being discarded and safeguarded in a memory and research center9, contributing to reflections on school practices in dialogue with other documentary sources.

From the various daily practices, the school collaborates for the social and cultural construction of the subjects that are part of it. In this study, it is not intended to explore how commemorative dates activities are planned, organized, and carried out, as observed in Tonholo (2013), who explored commemorative dates in the school context; Palauro and Tomazetti (2016), who discussed commemorative dates and planning for Early Childhood Education; and Linhares (2018), who explored aspects of continuing education in relation to working with commemorative dates.

Furthermore, the present study did not aim to contextualize how these activities are or should be approached in school contexts. Therefore, this article proposes to explore the historical understanding of this school practice, which permeates times and spaces and which was consolidated in the educational field, because, as emphasized by Benito (2017, p. 119), “[...] the school itself, through its practices, creates, codifies and transmits cultural models”.

Thus, for this text, the main sources of the investigation were compared, represented by the set of commemorative cards, and in complementary sources, such as Revistas do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul, the school reports of the students who produced the cards and the books Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro (1st and 2nd semester), by Amaral Fontoura (1967a, 1967b).

Based on this premise, the article was organized into three blocks: (a) initially, the introduction, already presented above, in which elements of the historiographical turn in the educational field are briefly discussed; (b) in sequence, the theoretical and methodological aspects used for data organization and the dialogues with other sources, as well as the derived reflections were problematized; (c) and, finally, the final considerations are presented, summarizing and indicating some produced perceptions.

The box of kept artifacts: a brief contextualization

Some aspects related to the context and search movement for these materials have to be exposed, which encompasses the process of conservation and donation. In personal and family archives, there are true treasures and, to find them, an investigator attentive to details and clues and willing to exercise this artisan gesture is necessary (Farge, 2017), characteristic of those who propose to operate with these particular sources, that is, who proposes to manually manipulate the sources and can interpret them.

By knowing these possibilities, and understanding that safeguarding the memory of many families and the cultural and social relations they experienced is/was limited to old crates and trunks, old suitcases, and spaces of little visibility, this study entered the field of familial kept ones. These kept artifacts can be analyzed from the perspective of personal files; in addition, they allow for a series of developments, due to the diversity that materials generally offer, due to people’s desire to keep objects and store them on paper (Cunha, 2019), for example, letters, diaries, cards, notes, etc. In this sense, it is highlighted that the simple durability of the artifact “[...] already makes it capable of expressing the past” (Menezes, 1998, p. 90). Thus, artifacts are documents and, under this understanding, the way they are perceived is modified and redirected, as one seeks and operates with objects and materials, that is, with sources.

When searching for materials in familial kept ones, there were still, lost or abandoned, in the sheds of the house located in the rural area, dusty boxes and old bags, with many artifacts related to the world of writing and the school context. For some reason, some books, notebooks, school reports, assorted invitations, and various cards were saved from fire and/or disposal, which portray the family’s possible relationships with written culture. With this, the possibility of investigating the materiality of school contexts arises, mainly through the artifacts put under discussion: cards that allude to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day celebrations and school report cards.

Immediately, the safeguarding of the material was guaranteed, given that it was donated to an institutional archive specialized in primary schooling. The kept cards belonged to 12 siblings (six men and six women) who concomitantly attended the space of a multigrade school in the locality, an aspect proven both by the set of cards produced on commemorative dates and by the set of school report cards.

From kept artifacts to sources: opening the cards

Benito (2017) considers that the daily production of the school, in particular, that of the classroom, is an important representative element that allows the interpretation of school culture and school material culture. Felgueiras (2015, p. 170) also highlights the importance of safeguarding sources for the field of History of Education and defends “[...] the assumption of materiality as a very productive perspective in understanding the educational process and as a means of unexpectedly reaching the actors, mediated by the objects [...]”, with the simultaneity and complexity of the relations arranged between actors and objects in this production being clear. According to the author:

Sheets, ballpoint pens, white walls, school furniture, buildings, lab coats, and notebooks, in their materiality, are signs of belonging to a culture. Artifacts do not have a single meaning, the true one, established once and for all, but a set of possible ones, existing in parallel. There are a whole series of possibilities of use that can be attributed to them, of which only a few will be possible, since their use is limited by the set of norms and values, of more or less conscious, explicit, and implicit representations. Objects acquire meaning from a network of other objects and people who, when using them, leave the mark of their practices and also constitute other subjects (Felgueiras, 2015, p. 182).

Thus, when choosing the set of artifacts that allude to the celebrations of Mother’s Day and Father’s Day as potentiators of reflections on school material culture, a first question comes to the fore, namely: the nomenclature to be used to define them, bearing in mind that the materials are linked to commemorative dates, relate to historical events and cultural rituals of certain contexts and refer to the aspects and customs and/or tradition of certain societies. They are inserted in the school institution to represent a relationship between the school and the social environment and can be classified, according to Tonholo (2013), as civil, religious, or cultural.

Thus, we decided to call them cards alluding to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day celebrations, considering the physical characteristics, materiality, and purpose constituting them, with special attention given to the type of paper used (cardboard10), their formats (rectangular, graphic stereotypes, shutter) and the varied props that compose them (ribbons, decals, cutouts, and collages).

The set of artifacts consists of a total of 35 cards, 12 cards sent to the father and 23 sent to the mother. Of the total number of cards, 11 do not have a date record; while the other 24 cards correspond to the period between 1964 and 1980, as can be seen in Table 1, with a detailed record of the periodization of the cards.

Table 1 List of cards per year

| Número | Ano |

|---|---|

| 4 | 1964 |

| 8 | 1965 |

| 1 | 1966 |

| - | 1967 |

| - | 1968 |

| 1 | 1969 |

| - | 1970 |

| 1 | 1971 |

| - | 1972 |

| 1 | 1973 |

| 1 | 1974 |

| 2 | 1975 |

| 1 | 1976 |

| 1 | 1977 |

| 1 | 1978 |

| 1 | 1979 |

| 1 | 1980 |

| 11 | Sem data |

| 35 | Total |

Source: the authors (2022).

When observing the data in Table 1, the absence of cards for certain periods does not necessarily mean that they were not produced in those periods. Among numerous possibilities, the materials may have been lost or misplaced, or they may also correspond to cards without date identification, a very plausible hypothesis.

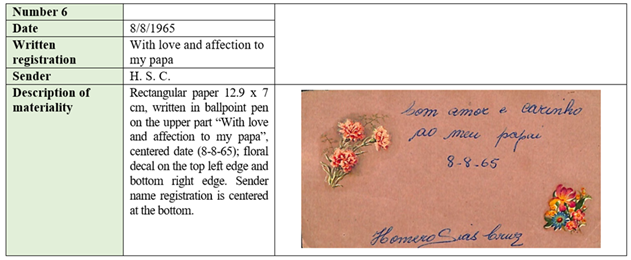

From the number of productions and their periodization, a descriptive box was organized for each card, which contemplates, in detail, the materiality of the cards (format, type of paper, text, handwriting, writing instrument, adornment material, and card image). At this time, only one of the examples in Table 1 will be explained, to show that this organization is considered a methodological aspect of the production of research data.

The information organized in Box 1 refers to the peculiarity of the artifacts and allows an overview of the set. In this way, it is possible to observe the choice of graphic elements in the close periods, the coexistence of productions, and the differences over the analyzed period.

This empirical sample of materials indicates that they can provide some problematizations about the constitution of the school’s culture, which is organized, according to Benito (2017), by the interconnection of empirical culture, scientific culture, and political culture. In this sense, the political culture and the scientific culture are represented by the indications disclosed in the pedagogical printed matter and school report cards, complementary sources of the research. The empirical culture, in turn, is seen in the significant expression of the production of the cards, as it is the representation of the teachers’ knowledge, produced, adapted, and shared in the daily practice of the classroom over the years as a school practice.

In addition, when analyzing the set of cards, this analysis is reflected and related to the concept of materiality by Chartier (2014, p. 37), “[...] as the modality of its inscription on the page or its distribution in the written object”. In this sense, the very inscription of the text together with the formats of the card (hearts, little windows, decals, flowers, etc.) and the materials used in its manufacture launches different ways of reading, considering the support and the text inserted. Based on this materiality, the relevance of making something for the mother and father can be seen in the set of cards and the organization of the writing support, a commitment in the choice and use of graphic elements, such as the decal of flowers and other images. Thus, there is affection and respect inscribed in the productions, as well as one can consider that, when keeping this material, this affective and respectful reading was also carried out by the recipient subjects.

In addition to these aspects, which constitute the concept of materiality and are present in the set, it is possible to visualize, by the production of the cards, by the signs and marks that compose them, the materials and instruments used for making them; for example, the different formats, types of paper, applications of small figures, cutouts, collages, and folding. It is also necessary to pay attention to the particularities of the written record (types of letters, writing position, insertion of lines), as these elements indicate the action of the teachers and students in the composition of the artifacts.

Regarding the written records, the texts are diverse, not very extensive, and may have been (re)produced by the teachers, written spontaneously by the children, or copied by them. This diversity was verified by the materiality of the texts, in which aspects referring to the handwriting (by the child and the teacher) and the graphic organization of the lines were observed. The following excerpts exemplify some of the records presented in the cards that were copied by the child: “A good mother, on this day, a kiss”, without a defined date; “Dear mother, on this day of yours, I want to greet you with joy”, in 1971. And reproduced by the teachers: “Happy August Sunday. Memory of Father’s Day”, in 1964; “To my daddy best wishes”, in 1965.

In addition to the messages of affection, this study identified the following text on the “Mommy” card, dated 9/5/1971: “Tomorrow at 3 o’clock, come to school to be honored”. The excerpt expands and confirms the perception that this practice, related to commemorative dates, configures the school environment and presents multiple possibilities for development, as it is evident that, in addition to the material production of cards, another type of tribute activity was carried out, which unfortunately is not explicit in the record; however, when this information is related to data from complementary sources, it is suggested that they may be artistic, musical or theatrical.

The possibility of dialogue with other materials contributes to the understanding and reflections on these artifacts that constitute such school practice. For this understanding, we operated with complementary sources, such as the set of school report cards11, Revistas do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul, and books Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro (1st and 2nd semester), authored by Amaral Fontoura, of the year 1967. The approximations occurred mainly by verifying information on the theme and by indicating activities to be carried out on the dates.

The student’s school report cards were selected because they indicated the school establishments where they were produced and which teachers guided the teaching and production of the cards in the period, as well as to relate the materialities with the aspects of the school curricula, verifying to which subject this manual practice could be linked. It is inferred that it was associated with Applied Arts, a subject that appears in school report cards during the analysis period.

Based on the data from the school report cards, it was possible to identify two schools, both multi-grade and located in the rural area: the school unit called Escola Conselheiro Cândido Batista de Oliveira; and a second, characterized in the school report as “No denomination”, presenting only its locality, in the rural area, called Corredor dos Cruz. In both teaching establishments, the data recorded in the school report cards indicate that the composition of the teaching staff was, in its entirety, female.

In addition, from the report cards, it was possible to see that all school classes, from the 1st to the 5th grade, produced the cards, as the dates of the report cards were crossed with the dates of the cards produced. From this point of view, the production of the cards constitutes a school practice experienced by the different grades in the pedagogical work in a multi-grade school in which the different grades shared the space of the classroom and school practices and were possibly taught by the same teacher.

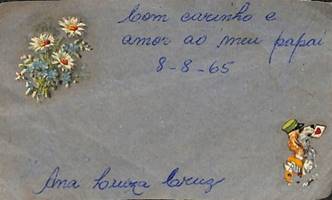

When observing the artifacts from 1964 and 1965, it is estimated that they were produced by the same teachers in a standardized way, made with the same material (rectangular, type of paper and decals) and calligraphy; moreover, they have the same text: “With love and affection to my papa”12 or “With affection and love to my papa”, as shown in Figure 1. In these two years, a total of 8 cards were sent to papa (3 cards from 1964 and 5 cards from 1965), produced by the teacher for different children. The analysis indicates that there was only variation in the decal used to illustrate the card, in addition to the variation of the child’s name.

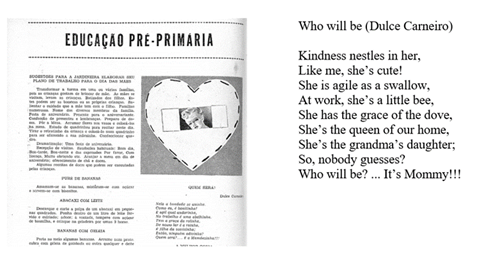

As previously mentioned, Revista do Ensino was also analyzed, as it was characterized as an important educational magazine produced in Rio Grande do Sul between the 1930s and 1990s13. This aspect of guidance to primary school teachers of the pedagogical print matter was what initially allowed the first reflections to take place and the dialogue between what was proposed in the magazine for the commemorative dates and the production of the cards analyzed. In this pedagogical print, some clues for problematization were identified, such as some production models very similar to those of the analyzed cards and an indication of other activities that would be carried out on the dates.

In the cards with a heart shape of the year 1965, referring to Mother’s Day, it is clear that the basic model was the same, with the writing and drawings possibly being made by the students. In Figure 2, below, the heart models are presented; although they are similar in format, distinctions in their materiality can be seen, for example, in the types of paper, in the written records, in the different forms of ornamentation (drawings with colored pencils, floral decals, collages, ribbons), in the instruments of writing (graphite pencil, felt-tip pen, and ballpoint pen) and, specifically in card B, a type of ink for coloring and drawing, in which there is a touch-sensitive aspect, as a different texture is perceived. The shutter model is also repeated over the years and differs in the previously mentioned aspects.

Source: Collection of the research (2022).

Figure 2 Cards with heart designs: (a) Dear Mother (1965); (b) To my dear mother (n.d.); (c) Save the 10th of May (n.d.) and (d) Pretty Mom, I love you (n.d.).

In the set of cards, exemplified in the objects exposed above, all the cards with the heart model were delivered to the mother. The heart is the symbol of affectivity, exercising the symbology of sacred love. However, the question is: why was this model offered only to the mother? Or it was necessary to affirm love for the mother with the use of affective symbols, represented by the heart; while, for the father, as a form of respect for the hierarchical family figure, were other ways sought to symbolize this love, such as the hat, the tie, and even the pipe? From the materiality of the cards, it is possible to infer that there are differences that configure father and mother roles in society, as well as observe that these differences are constituted in the school space by the practices carried out.

When carrying out data collection in Revistas do Ensino, a series of proposals that guided the work and productions in these festive periods referring to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day were confirmed. The guidelines range from manual activities to making utilitarian and decorative objects, reading poems, performing dramatizations, and including song lyrics, with the presence of the aforementioned scores. These indications consolidate the hypothesis and data from the 1971 card, that other activities beyond card production were carried out in the school context.

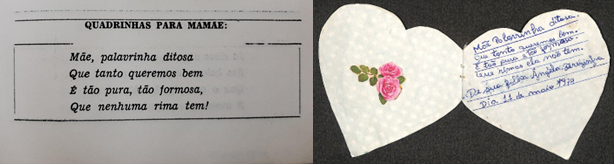

In a publication by Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul (1952, p. 22), there are “Suggestions for the pre-school teacher to prepare her work plan for Mother’s Day - [...] Making gifts and souvenirs. Study of four-line poems to recite on this day”. Nominations are accompanied by a template similar to the cards presented, shown below in Figure 3.

Source: Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul (1952, p. 22).

Figure 3 Suggestions for teachers to prepare their work plan for Mother’s Day.

From the above, the production of commemorative cards for dates such as Mother’s Day and Father’s Day is a school practice historically constituted and that makes up the school culture, based on the evidence of materialities, as this production represents, as Benito (2017, p. 119) states, “[...] a set of practices and discourses that regulated or regulate the life of formal education institutions and the teaching profession”. It is also possible to perceive, both by the guidelines of the Revista do Ensino, and by the school tradition and by the very materiality of the artifacts, that this educational practice composes particularities of the school curricula, setting the tone for the various pedagogical proposals, generating projects and work themes in the various school contexts. These activities make up the school memory of children (students/children) and their families.

There is, in a way, a close link between commemorative dates and the identity formation of a society, as they are configured as a cultural and social construction and enter multiple spaces of formation, which may vary from one context to another, but reaffirm their purpose. The fact is that the school plays a role in this construction, mainly because it often organizes the curriculum and educational practices based on commemorative dates, exposing/imposing civic, religious, moral, and family aspects to the subjects who attend it, assuming a decisive role in its cultural (re)elaboration.

These statements are corroborated by the publication of Revista do Ensino in August 1962, which indicates “Suggestions of activities for Father’s Day”. The text mentions the importance of the father figure for the children in the family context, and highlights the family as a social structure, in which good coexistence and the first insertion in the concepts of authority and hierarchy must be privileged, with the figure of the father especially highlighted, as can be seen in the following excerpt:

Taking place on the 2nd Sunday of August, the “DADDY’S DAY”, a date of great importance for the child, as the father has so much significance for them, the teacher will have a great opportunity to take them to the integration of new learning. The work can be started by directing the child in the sense of knowing their own family. They must be awakened to love the home, and the people who make it up and to have attitudes of respect and cooperation in the family environment.

[...]

The father is therefore an authority in the home.

Starting from the notion of authority within the family environment, where the father is the leader, students will be able to better understand the meaning of political and administrative authority (Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul, 1962, p. 16, emphasis added).

The suggestions for the work on the commemorative date evidence the father as an authority within the family environment. For this reason, the commemorative date in question constitutes itself beyond the affective nature and starts to configure as a moralizing and disciplining culture of a social order that historically assigns different and superior places to the father in relation to the mother.

These would be the learnings that the magazine suggests when stating that “[...] will the teacher have a great opportunity to lead them to the integration of new learning [...]”, pointing out a way to help the child to understand political and administrative authority? Perhaps these aspects are indicative of how a certain culture and tradition are socially constituted and (re)produced by school practices.

The indication that manual productions are guided by the teacher is also observed, as indicated in the pedagogical printed matter: “With the help of the teacher, the students will be able to create the ‘family album’, where they will put photos of the family members, mentioning the dates or events they related” (Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul, 1962, p. 16, emphasis added). In the publication, the importance of Father’s Day is mentioned to bring fathers closer to the school. Furthermore, there is an indication of the organization of the Circle of Parents and Teachers: “A great occasion for the installation of this Circle would be at a party in honor of the parents” (Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul, 1962, p. 17). In this sense, the practice also brings families closer to school contexts and, by indicating this possibility on “Father’s Day”, suggests that the father should have this connection with the school control of the children so that this possibility is not limited to mothers, since, according to the data, they must attend school on the indicated dates to receive tributes.

Therefore, when considering the two volumes of Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro, by Fontoura (1967a, 1967b), already mentioned as a complementary source for this investigation, the presence of these dates can be observed with indications of practical work to be carried out in schools by teachers and with the presentation of the history of said dates. In Fontoura (1967a), there is mention of the definition and history of Mother’s Day. Furthermore, in the succession of 48 pages about the date, there are suggestions of four-line poems and poems to be used in celebrations related to Mother’s Day. One of the sections is related to Mother’s Day and Abolition, with a suggestion for a dramatization for second- and fourth-grade classes.

Similar to that observed in the Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul (1962) about Father’s Day, with ‘great importance for the child”, it is verified, in Fontoura (1967b), first, the definition for the date of Father’s Day and, later, the history of the celebration in Brazil and suggestions of poems dedicated to Dad.

DAD’S DAY

DEFINITION - After having created a ‘Mother's Day’, so celebrated in almost every country in the world, it was only fair that a special ‘Day’ was also created to honor fathers. But it happens that, when speaking in the plural, ‘the parents’, the expression encompasses the father and the mother: ‘Joaquim and Ana are Maria’s parents’. So, just to characterize the figure of the father, it was decided to resort to that affectionate diminutive: ‘the daddy’ (Fontoura, 1967b, p. 41, emphasis added).

In the explanation, the work with the commemorative date of Father’s Day arose from the need for a “special day to honor fathers” and it is indicated that, to differentiate it, concerning the reference to parents in the plural, the characterization referring to the father in a diminutive way would be enough; this fact is not very convincing, since, in the description, it is necessary to distinguish it from the date of the mother, that is, there is the need to “characterize the figure of the father only”.

In this sense, about commemorative dates problematized in the investigation, as well as about the fact that different emphases are given to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, we refer to what Hobsbawm and Ranger (2008, p. 9) defined as invented tradition: “[...] a set of practices normally regulated by tacitly or openly accepted rules; such practices, whether ritual or symbolic in nature, aim to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior through repetition”. According to the authors, such traditions are constructed, invented, and formally institutionalized, as discussed in the production of cards at school and the guidelines that reached the school via guidelines in the pedagogical printed matters, as discussed in this work. Thus, the school constitutes a moralizing form of guidance between the family figures of the father and mother, starting to give social legitimacy to the dates, as already mentioned throughout this study.

The reflection on the invented tradition corroborates the idea that schooling is - although this relationship is much more complex - one of the fundamental mediators of the insertion of individuals, families, and social groups in the cultures of writing (Galvão, 2002) and in certain cultural practices. This multiplicity is manifested by the set of analyzed cards and by the indications/suggestions of work with the commemorative dates verified in the complementary sources.

In the suggestions for activities identified in the complementary sources, emphasis is given to the indication of poems and four-line poems referring to the two commemorative dates. As for the set of cards analyzed, the presence of four-line poems stands out, which appear in the vast majority of the analyzed material. Below, an example of writing on the card and what was found in the book is presented (Figure 4):

By observing the text suggestions (four-line poem) and by identifying the text on the cards, it is inferred that the teachers used and/or adapted the proposals to work in the classroom spaces. These elements also indicate the plural constitution of a certain school tradition, represented here by the practice of making cards in honor of mothers and fathers, as the suggested activities encompass different possibilities and different forms of work.

Thus, it is necessary to consider that teaching work and the activities characterizing it are organized in a way determined by tradition; or, as characterized by Benito (2017, p. 23), referring to the activities, “[...] over time, they have been bequeathed as a legitimate pedagogical heritage, that is, as practices transmitted by the ethos and custom established as tradition”. When reflecting on the tradition of this school practice of making cards alluding to commemorative dates, especially Father’s Day and Mother’s Day, it is possible to notice that it is a recurrent and present practice in the current school scenario, many times, with another guise and approach and that, moreover, it is expected and demanded by families. This reverberates the social and family legitimacy of the school practice of honoring and registering dedicated to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, disregarding, in a way, the multiple current family possibilities and maintaining the tradition of school culture.

Final remarks

By articulating the notions of school culture and school material culture, a wide range of possibilities opens up, including the investigation of the materiality of production, from which the cards alluding to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day are inserted. These artifacts are peculiar and represent a poorly explored source, which reverberates multiple aspects of the school’s materiality, mainly concerning the materials used in writing and the types of paper, which allows an unexpected, but fruitful, approximation with the material production of this practice present in the doing of the school.

In addition to the materiality of the cards, the commemorative dates of the Fathers and Mothers are configured as an invented tradition, beyond the affectivities the dates impose. It is about inserting a social and moralizing discussion of the different roles of father and mother and a standard family structure that is implicit and/or explicit in the indications and pedagogical guidelines of Revista do Ensino, the book Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro (1st and 2nd semester) and the texts and models of the cards, highlighting the relationship of these productions with the imposition of a profile of mother and father and family structure. The meanings created in making the cards at school also end up producing a family structure, whose focus is centered on the figure of the father as a standard of hierarchy and discipline. Thus, for this overlap to be mitigated, it would be enough to resort to the diminutive of the word, that is, “daddy”. For the mother’s date, on the other hand, the words used in the four-line poems and cards are “pure” and “beautiful”, among others.

Invented tradition, from the perspective of Hobsbawm and Ranger (2008), is configured from an institutional rule of the school, whose gateway is the school curriculum. With each new commemoration full of affection, the school reinforces and maintains the family structure before society, with father, mother, and childhood standards, based on a curriculum that supports these standards. Finally, it is possible to state that this discussion does not end here and that the production of these artifacts, cards alluding to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, will allow for other explorations and discussions of the school curriculum that have not yet been addressed.

REFERENCES

Bastos, M. H. C. (2005). A Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul (1939-1942): o novo e o nacional em revista. Pelotas, RS: Seiva. [ Links ]

Bencosta, M. L. (Org.). (2007). Culturas escolares, saberes e práticas educativas: itinerários históricos. São Paulo, SP: Cortez. [ Links ]

Benito, A. E. (2000). Las culturas escolares del siglo XX: encuentros y desencuentros [As culturas escolares do século XX: Encontros e desencontros]. Revista de Educación, 1, 201-218. [ Links ]

Benito, A. E. (2010). Patrimonio material de la escuela e historia cultural [Patrimônio material da escola e história cultural]. Revista Linhas, 11(2), 13-28. [ Links ]

Benito, A. E. (2017). A escola como cultura: experiência, memória e arqueologia. Campinas, SP: Alínea. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. (1988). A história cultural: entre práticas e representações. Lisboa, PT: Difusão Editorial. [ Links ]

Chartier, R. (2014). A mão do autor e a mente do editor. São Paulo, SP: Unesp. [ Links ]

Cunha, M. T. S. (2019). (Des)arquivar: arquivos pessoais e ego-documentos no tempo presente. São Paulo, SP: Rafael Copetti. [ Links ]

Dussel, I. (2014). A montagem da escolarização: discutindo conceitos e modelos para entender a produção histórica da escola moderna. Revista Linhas, 15(28), 250-278. https://doi.org/10.5965/1984723815282014250 [ Links ]

Farge, A. (2017). O sabor do arquivo. São Paulo, SP: Edusp. [ Links ]

Felgueiras, M. L. (2015). Para uma fundamentação da cultura material das práticas educativas. In W. Gonçalves Neto, E. F. Sá, & R. H. S. Simões (Orgs.), Circuitos e fronteiras história da educação (p. 169-184). Vitória, ES: Edufes. [ Links ]

Fontoura, A. (1967a). Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro: 1º semestre (Vol. 12). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Aurora. [ Links ]

Fontoura, A. (1967b). Educação cívica e calendário cívico brasileiro: 2º semestre (Vol. 13). Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Aurora. [ Links ]

Frago, A. V. (2008). La escuela y la escolaridad como objetos históricos: facetas y problemas de la historia de la educación [A escola e a escolaridade como objetos históricos: Facetas e problemas da história da educação]. Revista História da Educação, 12(25), 9-54. [ Links ]

Galvão, A. M. O. (2002). Oralidade, memória e a mediação do outro: práticas de letramento entre sujeitos com baixos níveis de escolarização: o caso do cordel (1930-1950).Educação & Sociedade, 23(81), 115-142. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302002008100007 [ Links ]

Hobsbawm, E., & Ranger, T. (Orgs.). (2008). A invenção das tradições. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Paz & Terra. [ Links ]

Julia, D. (2001). A cultura escolar como objeto histórico. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 1(1), 9-43. [ Links ]

Linhares, A. M. (2018). A formação docente continuada para datas comemorativas (Dissertação de Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria. https://repositorio.ufsm.br/handle/1/17147 [ Links ]

Menezes, U. T. B. (1998). Memória e cultura material: documentos pessoais no espaço público. Estudos Históricos, 11(21), 89-104. [ Links ]

Palauro, M. M., & Tomazetti, C. M. (2016). Datas comemorativas na educação infantil: quais sentidos na prática educativa?Crítica Educativa, 2(2), 150-164. [ Links ]

Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul. (1952). 1(6). [ Links ]

Revista do Ensino do Rio Grande do Sul. (1962). 9(86). [ Links ]

Tonholo, T. B. (2013). Data comemorativas no contexto escolar. Revista Eletrônica Pro-Docência/UEL, 1(4), 182-193. [ Links ]

9This study was carried out within the framework of Hisales investigations. Hisales - History of Literacy, Reading, Writing and School Books - is a memory and research center, established as a complementary body of the School of Education (FaE), of the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), which includes teaching, research, and extension. Its main policy is to guard and preserve the memory and history of the school and to carry out research. It is an archive specialized in the themes of literacy, reading, writing, and school books, made up of different collections. Hisales is also a research group registered in the Directory of Research Groups of CNPq since 2006. It is located at Campus II - UFPel, Rua Almirante Barroso, 1202 - Sala 101 H, CEP 96.010-280 - Pelotas/RS. More information about the collections, teaching, research, and extension activities can be found online at www. ufpel.edu.br/fae/hisales/, on the social networks Facebook and Instagram: @hisales.ufpel, and by email: grupohisales@gmail.com.

10Cardboard paper - type of paper used in graphic printing and school productions, popularly called cardstock, with a thickness of less than 0.5 mm.

11The complete set consists of 25 school report cards. In this article, only 14 cards were considered that comprise the temporality of the study.

30How to cite this paper: Thies, V. G., & Monks, J. C. ‘Dear mommy, dear daddy’: the invention of a school practice (1964 - 1980). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, 23. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v23.2023.e277

Received: September 29, 2022; Accepted: March 29, 2023; Published: June 30, 2023

texto en

texto en