Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Internacional de Educação Superior

versão On-line ISSN 2446-9424

Rev. Int. Educ. Super. vol.8 Campinas 2022 Epub 12-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.20396/riesup.v7i0.8663449

Article

Internationalization and Portuguese as a Foreign Language (PFL): Survey and Discussion*

1,2Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo

This study aimed to survey the offer of courses of Portuguese as a Foreign Language (PFL) in Brazilian higher education institutions (HEIs), discussing the offer of these courses in relation to the process of internationalization. With that aim, data from 60 Brazilian HEIs were collected through an online questionnaire, in order to support the discussion of the relationship between PFL and internationalization, based on the literature reviewed and data collected. Results indicate that most institutions offer PFL courses, the Southern region has the greatest representativeness in the offer of PFL courses, the departments of Languages and international relations (taken together) are responsible for great part of this offer. The discussion of results suggests a relevant connection between PFL and Internationalization at Home (IaH). Conclusions suggest that, despite the efforts of HEIs to offer PFL, more investment is necessary to develop IaH, in order to promote social justice.

KEYWORDS: International education; Portuguese; Social justice

Este estudo teve como objetivo fazer um levantamento da oferta de cursos de português como língua estrangeira (PLE) em instituições de ensino superior (IES) no Brasil, discutindo essa oferta em relação ao processo de internacionalização. Para tanto, foi realizada uma coleta de dados em 60 IES brasileiras, por meio de questionário eletrônico, para subsidiar a discussão da relação entre PLE e internacionalização, com base na literatura revisada e nos dados levantados. Os resultados indicam que a maior parte das IES oferta cursos de PLE, sendo que a região Sul tem a maior representatividade na oferta, e os departamentos de Letras e setores de relações internacionais (em conjunto) respondem por quase toda essa oferta. A discussão dos resultados sugere uma estreita relação entre PLE e o processo de Internacionalização em Casa (IeC). As conclusões sugerem que, apesar dos esforços para a oferta de PLE nas IES, mais investimentos são necessários para o desenvolvimento da IeC, de maneira a promover a justiça social.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Internacionalização da educação; Ensino da língua portuguesa; Justiça social

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo desarrollar una encuesta sobre los cursos de Portugués como Lengua Extranjera (PLE) en las instituciones de educación superior brasileñas (IES) y discutir la impartición de estos cursos en relación con el proceso de internacionalización. Por lo tanto, se recopilaron datos de 60 IES brasileñas a través de un cuestionario en línea, con el fin de apoyar la discusión sobre la relación entre PLE e internacionalización, con base en la literatura analizada y los datos recopilados. Los resultados indican que la mayoría de las instituciones ofrecen cursos de PLE, siendo la región Sur importante para la oferta de PLE, y los departamentos de Lenguas y relaciones internacionales (en conjunto) son responsables de gran parte de esta oferta. La discusión de los resultados sugiere una conexión relevante entre PLE e Internacionalización en Casa (IeC). Las conclusiones indican que, a pesar de los esfuerzos de las IES para ofrecer PLE, se necesita más inversión para desarrollar la IeC, con el fin de promover la justicia social.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Educación con vocación internacional; Portugués; Justicia social

Introduction

The social, cultural, political and economic processes entangled in globalization and late modernity are mediated by discourses, by the compression of time/space, and by information and communication technologies (ICTs). In the current scenario of super-diversity in which we live (VERTOVEC, 2007, 2019), individuals move between physical borders (currently, less frequently than before the pandemic) and virtual borders, where languages play a key role, affecting the flows of people, information and goods. These flows are, in turn, accelerated by globalization and ICTs.

Due to increasing exchanges promoted by globalization, which differently affect countries around the world, with more benefits for northern countries (VAVRUS; PEKOL, 2015; FINARDI; GUIMARÃES, 2020) or for the 'Global North’1 (SANTOS, 2011), it is important to discuss the sociolinguistic (and geopolitical) scenario of the Portuguese language, in relation to economic, political, social, cultural and technological changes (and others), created through internationalization practices, discourses and languages that move between physical and virtual networks - in which language users build their identities and meanings. In this sense, we see studies that have been discussing the role of Portuguese in the 21st century, as well as the sociolinguistic and geopolitical scenario in which Portuguese operates, such as the works of Moita Lopes (2013), Oliveira (2013), Signorini (2013), Fabrício (2013), Bagno (2013) and Lagares (2013), so as to expand this debate in the context of the internationalization of higher education.

Considering that globalization affects (and it is also affected by) internationalization, defined as the intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of higher education, in order to improve the quality of education and research, for all students and staff, and to provide a meaningful contribution to society (DE WIT et al., 2015) and despite the caveat made by Knight (2011) and De Wit (2011) that internationalization is not limited to academic mobility, we can see a significant increase in student mobility2 during the last decades before the pandemic. This mobility has encouraged more than 4 million students to study abroad, putting scholars from various cultural and language backgrounds in increasing contacts, resulting in challenges for institutions which welcome such scholars, and for all people involved in these intercultural and inter-language contacts.

After the pandemic outbreak, which limited the international mobility of people and affected the delivery of higher education (in general) and student mobility programs (in particular), these language and cultural exchanges increased even more, but in the virtual environment. According to Finardi and Guimarães (2020), before the pandemic, academic mobility was limited to a small number of elite students, moving from the Global South to the Global North. After the beginning of the pandemic, this model of internationalization and academic mobility was replaced by virtual academic mobility, supported by ICTs, with the inclusion of different agents and languages, and more ‘horizontal’ relations between countries, universities, languages and scholars worldwide.

Inward academic mobility programs to Brazil such as PEC-G3 (Program for the Mobility of Undergraduate Students) and PEC-PG4 (Program for the Mobility of Graduate Students) and PAEC-OEA5 (Program of Alliances for Education and Training, Organization of American States) have promoted the mobility of international students for decades to Brazilian HEIs. Such programs required participants to show proof of proficiency in Portuguese and/or participate in programs for the development of Portuguese language proficiency when they arrive in Brazil.

More recently, the institutional internationalization program called ‘Capes PrInt’, focused on the graduate level, has also promoted the academic mobility of Brazilian academics abroad and of international academics to Brazil, though this program does not require the proof of proficiency in Portuguese from international academics who come to Brazil. This lack of requirement is relevant because it represents evidence of the view of Capes PrInt concerning the role of the Portuguese language in international exchanges and in the process of internationalization as a whole.

In addition to this trend in student mobility towards Brazil, we also observe an increasing movement of immigrants and refugees looking for better life and work conditions, as reported by Câmara (2014) and Camargo and Hermany (2018), coming mainly from countries of the Global South such as Venezuela, Haiti, Pakistan, Syria, Angola, Senegal, Congo and Ghana - whose main destinations are the North, Southeast and South regions of Brazil. These immigrants frequently face situations of xenophobia, inadequate life conditions and pressures from the international traffic of people. Considering the important role of education (in general) and higher education institutions (in particular) for the integration of these migrant and displaced populations, it is important to consider policies for the promotion of PFL courses for these populations.

Due to this intense flow of people, HEIs in Brazil are facing many challenges to welcome these groups of international students, immigrants and refugees. One of the biggest challenges for welcoming these populations is related to the offer of courses of Portuguese as a foreign language (PFL) to allow the integration and participation of these people, through language, in the Brazilian society.

Thus, this study aims at discussing the current offer of PFL courses in Brazilian HEIs in relation to the process of internationalization. With that aim, we present a brief review of literature on PFL and its relation with internationalization processes in Brazil, and then present the methodology adopted in this study. The research problem includes the survey on the current PFL offer in Brazilian HEIs, to discuss this offer in relation to the process of internationalization of higher education in Brazil. So as to pursue this objective, the study adopted a qualitative methodology, including a review of relevant literature in the fields of PFL and internationalization, a survey on the PFL offer, using an online questionnaire, and data analysis with the support of MS-Excel software, to contrast the data obtained in the questionnaire with the literature reviewed.

Literature Review

The topic of PFL has been discussed by various authors such as Berber-Sardinha (1999), Dell’Isola et al. (2003), Almeida (2004), Gualda (2009), Salles, Holderbaum and Finger (2010), Moita Lopes (2013), Oliveira (2013), Signorini (2013), Fabrício (2013), Bagno (2013), Lagares (2013) and Aguiar and Albuquerque (2014). In relation to the main aspects addressed in these articles, Berber-Sardinha (1999) used corpora linguistics to deal with the teaching of Portuguese as a foreign language, indicating that existing teaching materials were not appropriate, considering that they did not present authentic samples of Portuguese language. Dell’Isola et al. (2003) discussed the assessment of PFL proficiency using the Celpe-Bras6 exam, indicating an increasing demand for this exam, which influences the teaching of PFL in Brazil and abroad.

Almeida (2004) reviewed the role of Portuguese around the world, highlighting the influences of globalization and the flow of goods/services using the Portuguese language. Gualda (2009) discussed teaching materials used in PFL courses, focusing on the creation of discourse and identity in these materials. Salles, Holderbaum and Finger (2010) carried out a comparative study on monolingual Brazilians versus foreigners who speak Portuguese. Aguiar and Albuquerque (2014) analyzed an outreach project aimed at integrating foreigners into the academic context through PFL teaching/learning activities, for speakers of other languages.

In addition to these authors, studies such as Guimarães (2020) highlight the increasing importance of PFL for the development of multilingualism, in the context of internationalization of federal universities, and De Wit, Leal and Unangst (2020) stress the relation between internationalization and social justice, focusing on the analysis of projects for the integration of refugees and displaced populations in Brazil. These authors emphasize the autonomy of Brazilian HEIs for the development of internationalization strategies seeking to promote social justice, and highlight the importance of HEIs activities/policies for welcoming marginalized groups, in institutional policies for internationalization.

As discussed by various authors, among which we highlight Lima and Maranhão (2009); Leite and Genro (2012); Baumvol and Sarmento (2016); Miranda and Stallivieri (2017); Streck and Abba (2018); Ramos (2018); Morosini and Corte (2018); Guimarães, Finardi and Casotti (2019); Guimarães and Kremer (2020), the importance of languages for the internationalization process in Brazilian HEIs is unquestionable. Taken together, these studies indicate the importance of languages for internationalization, a process in which Brazil acts in a passive way, focusing on welcoming international students from the Global South and sending Brazilian students to the Global North, and promoting English as the ‘international academic language’. Moreover, these authors highlight the centrality of languages in education and internationalization, especially when they are used as language of instruction, as discussed by Spolsky (2004) and shown in various contexts such as Brazil and Turkey (TAQUINI; FINARDI and AMORIM, 2017) and Brazil and Belgium (GUIMARÃES; KREMER, 2020), to name but two examples.

Considering the close relationship between languages and the process of internationalization, highlighted in the literature in the area (e.g.: FINARDI, SANTOS and GUIMARÃES, 2016), in this study we zoom in the role of PFL in this process. The main internationalization programs towards Brazil nowadays, such as PEC-G, PEC-PG and PAEC-OEA, attract hundreds of international students, coming (mainly) from Latin America and Africa, who use languages such as Spanish, French and English as first and/or official languages, requiring the offer of PFL at Brazilian universities, since most of the courses offered at Brazilian universities are in Portuguese only. Though some international students come from nations of the Community of Countries of Portuguese Language (CPLP, in Portuguese) such as Angola, Cape Verde and Mozambique, it is necessary to offer PFL for users of other languages.

The close connection between languages and internationalization can be expanded and deepened to incorporate the idea of ‘Internationalization at Home’ (IaH), which includes the intentional integration of international and intercultural dimensions into the formal and informal curriculum, for all students, in domestic learning environments (BEELEN; JONES, 2015). Unlike the view of internationalization as academic mobility, which usually involves sending students from the Global South to the Global North, and to Anglophone countries (DE WIT, 2020), the idea of IaH has a great potential to develop and expand exchanges between HEIs, promoting a more inclusive and just internationalization, from a social stance.

Definitions and ‘classic’ and/or ‘global’ concepts of internationalization were set forth and/or discussed by authors such as Knight (2003), Altbach (2004), De Wit et al. (2015) e Morosini and Ustárroz (2016), to cite but a few. However, the ‘local’ application of these concepts varies significantly in each context. Considering that most of the aforementioned authors are from the Global North, we follow Leal and Moraes (2018) who propose the approximation between the Latin-American epistemological perspective (e.g. LEAL, 2020) and the theoretical field of internationalization, acknowledging the epistemic roots and historical conditions of internationalization in Brazil. In that sense and in this study, we look at internationalization based on evidence of this process in the Brazilian context, through an analysis of language policies (e.g. GUIMARÃES, 2020) and internationalization programs such as Capes PrInt, PEC-G/PEC-PG and PAEC-OEA.

In Brazil, internationalization was propelled by the ‘Science without Borders’ (SwB) program, active between 2011 and 2017, sending more than 100,000 students abroad (mainly undergraduate ones). This program received fierce criticism and went through several problems, among which we highlight issues of low proficiency in languages (in general) and in English (in particular) of program participants, resulting in the creation of other programs at the national level to deal with these issues (FINARDI; ARCHANJO, 2018). The ‘English without Borders’ (EwB) program, created in 2012 to deal with this issue of proficiency of Brazilian students who were applying for SwB, was later expanded to include other languages besides English and was rebranded ‘Languages without Borders’ (LwB) in 2014. The focus of LwB in that period was offering opportunities for developing language proficiency, including PFL, through in-person classes, online courses and proficiency exams.

In 2017, the Capes PrInt program was launched, partially as an attempt to solve the issues which emerged after SwB, focusing on institutional internationalization, at the graduate level. This program includes both the mobility of Brazilians to other countries, and the mobility of international scholars to Brazil, focusing on the promotion of IaH, offering courses taught in English (EMI) at the graduate level, and PFL activities for welcoming international scholars, as can be seen in the EMI guide published by Faubai and the British Council7.

It is important to notice that, though the Capes PrInt program requires proof of proficiency in foreign languages from Brazilians going abroad through this program, this same requirement does not apply to international academics coming to Brazil, thus highlighting the lack of reciprocity in relations, concerning the use of foreign languages and PFL in this program. This lack of reciprocity can be understood as evidence of an implicit language policy in relation to PFL and a biased view of languages, downplaying the role of Portuguese as an academic language and a language for internationalization.

In order to expand the debate around the relation between languages and internationalization, the present study surveyed the current offer of PFL courses in Brazilian HEIs, discussing this offer in relation to the internationalization process in Brazil. In the following section, the methodology adopted in this study is described.

Methodology

In order to analyze the relation between PFL and internationalization in Brazilian HEIs, this study used the following question: What is the offer of Portuguese as a foreign language (PFL) courses like in higher education institutions (HEIs) in Brazil nowadays? To answer this question, a review of relevant literature was carried out and contrasted with a survey of offer of PFL courses in Brazilian HEIs, using an electronic questionnaire administered in August 2020. The questionnaire was piloted with teachers who work with PFL in university contexts and the adjusted model (after piloting) can be seen in the Appendix of this article. The questionnaire has 14 questions, with open-ended, dichotomous, multiple choice and single choice questions.

Invitations to participate in the online survey were sent by email to 448 addresses, obtained in websites from institutions such as Andifes (National Association of Managers of Federal HEIs), Faubai (Brazilian Association for International Education) and INEP (National Institute for Educational Research), as well as websites of federal universities - which include contacts of professionals who work with PFL in Brazil. After sending 448 messages, 60 participants replied our invitation for the survey, from HEIs located the five Brazilian regions. In the following section, we present the results of the questionnaire, before discussing them in relation to the literature reviewed. For the analysis of data obtained in the questionnaire, the MS-Excel software was used, comparing data with the literature reviewed.

Results

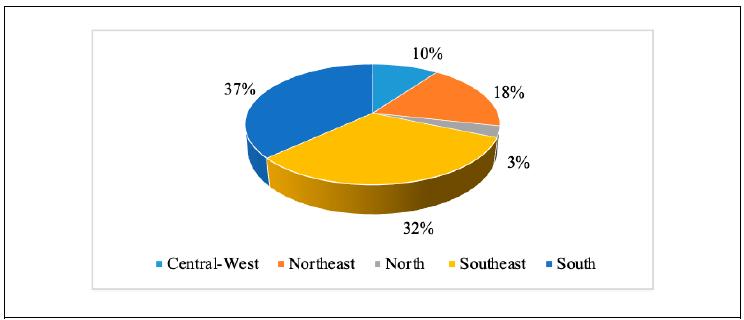

Question 1 (email) was included to register the email addresses of participants, in order to avoid duplicate answers during data processing. Question 2 refers to the Brazilian region in which the institution of the participant is located and data indicate a predominance of participants from the South (37%) and Southeast (32%), as can be seen in Figure 1. These data suggest a concentration of PFL courses in these regions, where most HEIs are located, as indicated in the Brazilian Higher Education Census8.

Question 3 refers to the state (UF) in which the institutions of participants are located. We can see a predominance of Minas Gerais (10), Rio Grande do Sul (9), Paraná (7), São Paulo (7) and Santa Catarina (6), as indicated in Table 1. These data suggest that the offer of PFL courses is concentrated in these states. It is important to notice that this predominance should be relativized, due to the number of HEIs in each state (for example, Minas Gerais has 22 federal institutions). That said, we noticed that the predominance of institutions from the South and Southeast remains.

Table 1 Distribution of participants by state (UF).

| UF | Qty. | UF | Qty. | UF | Qty. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 0 | Maranhão | 0 | Rio de Janeiro | 2 |

| Alagoas | 0 | Mato Grosso | 1 | Rio Grande do Norte | 2 |

| Amapá | 0 | Mato Grosso do Sul | 0 | Rio Grande do Sul | 9 |

| Amazonas | 1 | Minas Gerais | 10 | Rondônia | 0 |

| Bahia | 2 | Pará | 1 | Roraima | 0 |

| Ceará | 1 | Paraíba | 2 | Santa Catarina | 6 |

| Distrito Federal | 4 | Paraná | 7 | São Paulo | 7 |

| Espírito Santo | 0 | Pernambuco | 2 | Sergipe | 1 |

| Goiás | 1 | Piauí | 1 | Tocantins | 0 |

| Total | 60 | ||||

Source: research data.

Question 4 refers to the acronym/name of the institution in which the participant works, in order to identify the existence of more than one participant per institution. There were more than one participant in the following institutions: IFSC (2); UFPE (2); UFPEL (2); UFSC (2); UFTM (2); UnB (4); UTFPR (3). It is important to consider the size of HEIs with more than one participant, as in the case of UnB (4 participants), with 38,000 members, compared to UFPEL (2 participants), with 19,000 members. Participants’ institutions are indicated in Chart 1.

Chart 1 Participants’ institutions

| Centro Paula Souza | UEFS | UFJF | UFRJ | UnB |

| FAE Centro Universitário | UEM | UFLA | UFRN | UNESPAR |

| FURB | UESC | UFMG | UFS | UNICRUZ |

| FURG | UESPI | UFMT | UFSC | UNIFAL |

| IFAM | UFABC | UFOP | UFSJ | UNIFESP |

| IFPB | UFCSPA | UFPA | UFSM | UNILA |

| IFSC | UFERSA | UFPB | UFTM | UNILAB |

| IFSP | UFF | UFPE | UFU | UNISC |

| PUC-SP | UFFS | UFPEL | UFV | USF |

| UCS | UFG | UFRGS | UNAERP | UTFPR |

Source: research data.

Question 5 refers to the existence of PFL courses in the participants’ institutions. Data show that 87% (Yes) of institutions offer PFL courses, and 13% (No) of institutions do not offer PFL courses, indicating the relevance of PFL courses in the context of Brazilian HEIs.

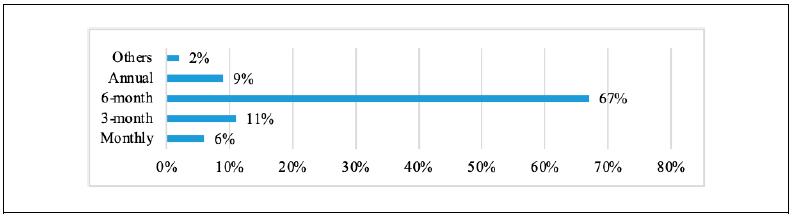

Question 6 refers to the regularity of PFL courses and indicated a predominance of six-month courses (67%), possibly matching the academic calendar of undergraduate/graduate studies in the HEIs where courses are offered, as indicated in Figure 2. The category ‘others’ (2%) included answers such as 2-month; 4-month; and on-demand.

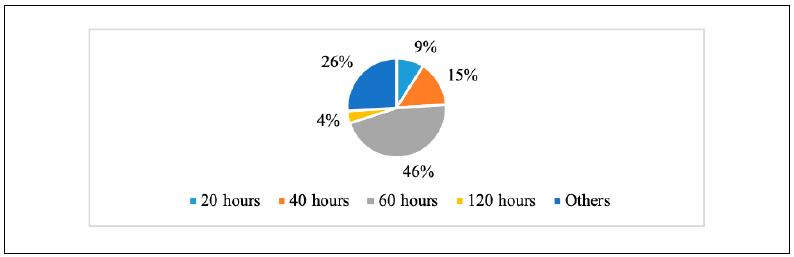

Question 7 refers to average course hours of PFL courses and indicated that the majority (46%) are 60-hour courses, although the category ‘others’ (26%) shows a variety in course hours offered (for example: 16h, 32h, 48h, 64h, 350h, 720h and 932h), as shown in Figure 3.

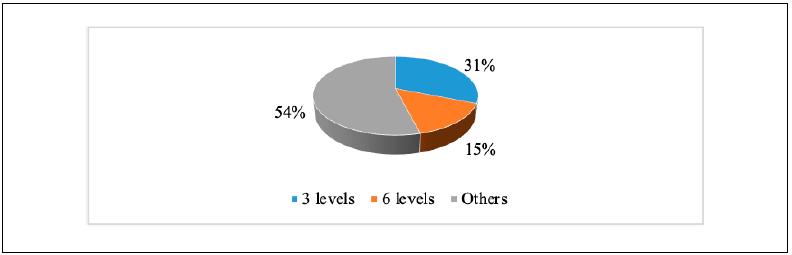

Question 8 refers to the number of proficiency levels in the courses offered, whereby a significant amount (31%) of answers indicates 3 proficiency levels, although the category ‘others’ includes a variety in proficiency levels (for example: 1 level, 2 levels, 4 levels, 5 levels, 8 levels), as can be seen in Figure 4.

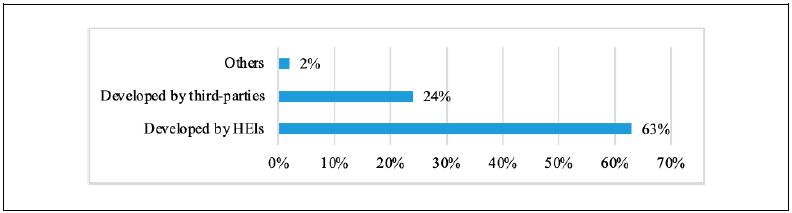

Question 9 refers to the course materials used in PFL courses, and shows a predominance (63%) of the use of materials developed at the very same institutions where the courses are offered, as can be seen in Figure 5. The category ‘others’ (2%) included answers such as a combination of materials (materials developed in HEIs plus materials supplied by third parties).

Question 10 analyzes the use of course materials supplied by third parties, in PFL courses - the following materials were mentioned: Bem-vindo (a língua portuguesa no mundo da comunicação); Brasil Intercultural; Clica Brasil; ETEC Idiomas; Falar, ler e escrever Português; Fale Português; Horizontes; Learning Portuguese; Mão na massa; Muito prazer; Avenida Brasil; Oi Brasil!; Pátria Brasil; Terra Brasil; and Viva!

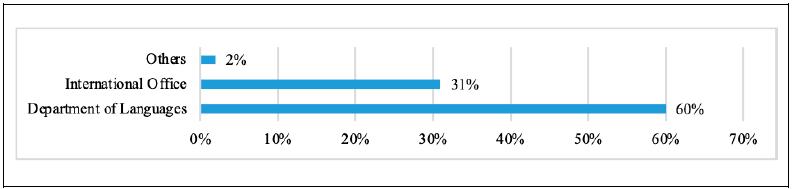

Question 11 refers to the division in HEIs where courses are offered, and we can see a predominance of the Department of Languages (DL or equivalent) comprising 60% of answers, as can be seen in Figure 6. The international office (IO) has also a significant participation (31%), suggesting a connection between languages and internationalization. The category ‘others’ (2%) included answers such as: a joint offer (DL + IO); Languages without Borders; language centers or institutes; Senior Office for Outreach; Senior Office for Research; and outreach projects.

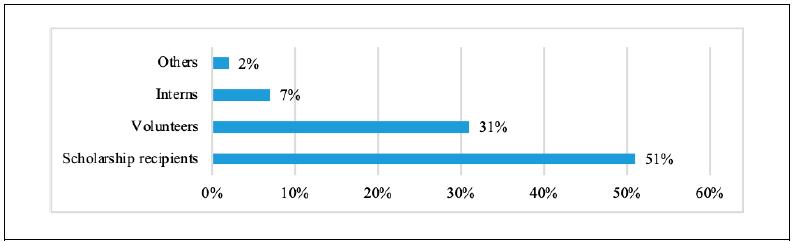

In relation to Question 12, concerning the type of teacher who works in PFL courses, we can see a dominance of scholarship recipients9 (51%) and volunteers (31%), as can be seen in Figure 7. These data are relevant because they can reflect how the PFL course offer is important (or not) for institutions, relegated (82%) to scholarship recipients and volunteers, who usually do not have a long-term relationship with institutions. These data can also reflect a lack of specific training in PFL in the undergraduate careers in Languages10. The category ‘others’ (2%) included answers such as: tenure track professors; members of the permanent university staff; professors in temporary positions; students from the careers in Languages; professors aided by interns.

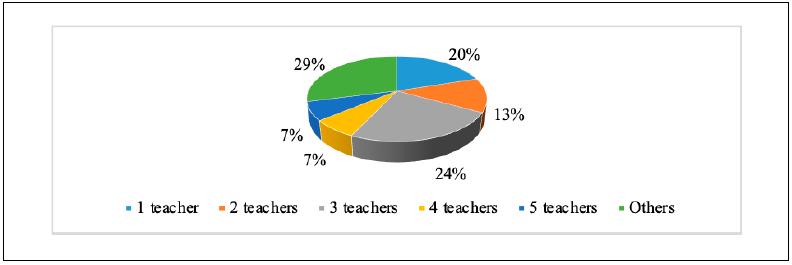

In relation to Question 13, concerning the number of teachers who work in PFL courses, we highlight small teams of teachers, as in the case of 1 teacher (20%), 2 teachers (13%), or 3 teachers (24%), as can be seen in Figure 8. The category ‘others’ (29%) included answers such as: 6 teachers; 10 teachers; 12 teachers; and 20 teachers (only one institution has this number of teachers).

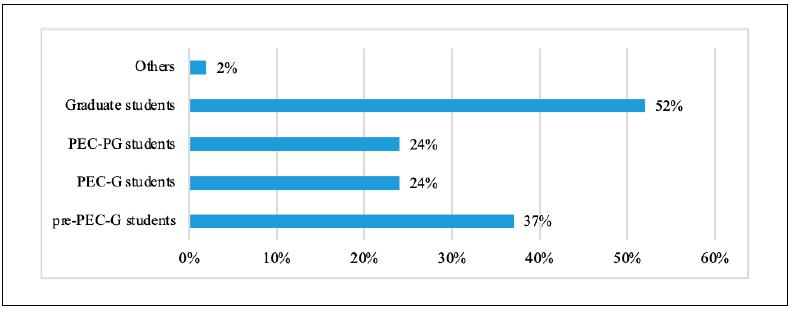

The last question, Question 14, concerning the target audience for which PFL courses are offered, indicated a predominance of courses for graduate students in general (52%), as can be seen in Figure 9. Once again one we can see a relation between languages (in this case, PFL) and internationalization, considering that nowadays the only internationalization program at the national level (Capes PrInt) is focused on graduate studies. The category ‘others’ (2%) included answers such as: external community (foreigners in Brazil, in general), immigrants, refugees, undergraduate students and exchange students.

Considering these results, obtained through the electronic questionnaire sent out to survey the offer of PFL courses in Brazil, in the next section we discuss the main findings of the present study, contrasting the literature reviewed with the survey data.

Discussion

The concentration of PFL courses in certain regions, mainly in the Southeast (32%) and South (37%) of Brazil suggests a need to invest and educate more teachers (considering that few HEIs offer training in PFL), in order to expand the number of PFL courses in the other regions, so as to supply an increasing demand that may exist in these regions.

We highlight that the Southeast region, which concentrates most of PFL courses does not share any border with other countries, while the North region shares borders with other countries (for example, French Guiana, Suriname, Guiana, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Bolivia), thus requiring more PFL courses, in order to welcome people coming from recent migration flows from these countries to Brazil. However, if we think about the academic mobility to Brazil, we see that the concentration of PFL courses in the Southeast and South is related to the most sought after destinations in Brazil by foreigners, suggesting a connection between PFL and internationalization, mainly in the case of IaH and academic mobility to Brazil.

In relation to the concentration of courses in certain states (UF), mainly in Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Paraná and Santa Catarina, we can see that the geographic position of states in the South region (PR, SC and RS) can influence the offer of courses, because they share borders with Paraguay, Argentina and Uruguay, countries of origin for many migrants coming to Brazil. In relation to states in the Southeast region (MG and SP), the significant offer of PFL courses can be linked to the search for job positions and education in this region, which concentrates a great share of the Brazilian11 population, as well as factories and services (including universities), becoming a point of interest for immigrants (in general) and students (in particular). In relation to the institutions which participated in the present research endeavor (Chart 1), their representation is in line with data from previous questions, about the region and state in which institutions are located.

In relation to the offer of PFL courses, we can see a significant percentage of institutions (87%) which offer this type of course, indicating the relevance of this activity for HEIs in Brazil and showing a relation between PFL and internationalization. However, we highlight that more resources could be channeled to PFL courses, mainly for the regions and states where few courses or teachers exist, as in the North region.

In relation to the regularity of PFL course offer, most institutions offer courses every 6 months, probably to match the calendar of academic courses in undergraduate and graduate studies. In relation to average course hours (CH), one can see a predominance of 60-hour courses, although there is a great variety in the CH of the courses offered (as indicated in the answers), due to the different audiences that such courses try to serve (undergraduate and graduate students, refugees, immigrants, external community, etc.).

Concerning the number of proficiency levels, we also see a great variety in the number of levels offered. Probably this occurs because of the specific needs of each institution, especially in relation to the level of demand for PFL courses, the number of teachers available and the different audiences that these courses try to serve.

In relation to course materials used in PFL courses, the adoption of materials designed in the very same institutions where courses are offered (63%) was observed in our data, although there is also a considerable use of materials designed by third parties (24%). Some answers also indicate an adoption of combined materials (local + third party). This is an interesting aspect because the development of course materials can support the professional development of students in the careers of Languages who work as scholarship recipients in PFL courses. On the one hand, it could indicate an active role of PFL teachers, exercising their agency skills and local sensitivity to design materials. On the other hand, the difficulties to acquire good materials may cause HEIs to ‘do what they can’, in order to provide students with PFL materials.

Concerning the divisions in charge of offering PFL courses, the great relevance of the departments of Languages (60%) for offering this type of course is highlighted in our data, although some institutions are supported by international offices (31%). The offer supported by international offices suggest evidence of the relation between PFL and internationalization. Senior offices for outreach and research (as shown in the answers) can also be an alternative to offer PFL courses, mainly in institutions which do not offer undergraduate careers in Languages (or do not have teachers with PFL skills in their staff).

In relation to the kind of teachers who work in the courses, one can see a predominance of scholarship recipients teaching PFL. Maybe some incentive programs are necessary for tenure track lecturers, including financial incentives, and policies for specific training in PFL, for those who need education in this field. Considering that in most institutions (51%) courses are taught by scholarship recipients, their short permanence (due to few incentives/safeguards for this type of work) can affect the continuity of courses, tough teaching PFL can be an opportunity of professional development for students in careers related to Languages. A balance in the participation of tenure track lecturers and scholarship recipients can be a good alternative to develop PFL courses.

Concerning the number of teachers who work in the PFL courses, data show small teams working in PFL courses, with 1 to 3 teachers, although some institutions have larger groups, with 10, 12 or 20 teachers. Probably, the number of teachers depends on the demand for PFL courses, but the current migration flows to Brazil, discussed by Câmara (2014) and Carmargo and Hermany (2018), suggest an increasing need to expand the number of PFL courses, in order to serve a growing population of immigrants and refugees, for instance.

In relation to the target audience of PFL courses, we highlight graduate students (in general), probably because of the current focus of internationalization in Brazil (Capes PrInt program) and programs to support academic mobility such as PAEC-OEA and PEC-PG. Pre-PEC-G students are also highlighted as target audience, because they first come to Brazil to learn PFL and eventually seek to be admitted in the PEC-G program, to start an undergraduate career here.

There is also a demand for PFL courses oriented to immigrants and refugees, probably because of the increase in migration flows to Brazil in recent years. These results indicate a relation between PFL and Internationalization at Home (IaH), as the PFL courses can promote the integration of international and intercultural dimensions into local contexts of Brazilian HEIs. In the following section we present our final remarks, based on the discussion presented here.

Final Remarks

This study aimed at identifying the current status of PFL course offer in Brazilian HEIs, discussing this evidence with the relevant literature reviewed. To this end, a survey of the offer of PFL courses in Brazilian institutions was carried out, using an electronic questionnaire, whose results were analyzed in comparison with the literature on PFL and internationalization.

Overall, results show: (a) concentration of PFL courses in the South (37%) and Southeast (32%) regions; (b) most surveyed institutions (87%) offer PFL courses; (c) courses are usually offered every 6 months (67%); (d) variety in the number of course hours and levels of proficiency; (e) predominance of course materials developed in the very same institutions where courses are offered (63%); (f) predominance of departments of Languages as the main institutional units offering PFL courses (60%); (g) predominance of scholarship recipients as teachers in PFL courses (51%); (h) small teams of PFL teachers, with 1 to 3 teachers to offer courses; (i) graduate students (52%) as the target audience of PFL courses, although courses for immigrants and refugees were also found.

Data discussion suggests a close relation between foreign languages (in this case, PFL) and the internationalization process, as shown in the literature reviewed. Evidence of this relation can be found in the role of foreign languages in internationalization programs, and (in our data) it can be found in the fact that international offices, along with departments of Languages, are the main units in charge of the PFL courses, in order to promote Internationalization at Home.

One of the limitations of this study is the fact that data were collected through a questionnaire which includes statements provided only by teachers who work in the field of PFL. Unlike the data collection in the EMI Guide (mentioned previously), in which answers were provided by institutional managers, data in the present research focused on statements from PFL teachers, not managers.

However, this limitation can also represent an advantage for the present study, as the institutional statements provided to the EMI Guide are mainly quantitative and may not reflect the reality of PFL in a given HEI, whether due to lack of information/knowledge of managers about the PFL activities or the lack of qualitative refinement as an alternative for answers. In this sense, the present study offers an up-to-date, qualitative and relevant analysis of PFL, by collecting data straight from the source, that is, teachers who work with PFL in HEIs.

This study concludes that, despite the efforts to offer PFL in Brazilian HEIs, more research is necessary to analyze PFL in Brazil, in a broad and relevant way, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, so as to promote more investment in the development of IaH through PFL, in order to promote social justice. In addition, more research is necessary to analyze the gap in the education of PFL teachers, considering the current scenario of internationalization.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, André Luiz Ramalho; ALBUQUERQUE, Fleide Daniel Santos de. Projeto de extensão língua portuguesa para a UNILA: a integração pelo ensino de Português como Língua Estrangeira. Revista SURES, Foz do Iguaçu, v. 3, p. 1-12, 2014. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Mario Sergio Pinheiro Moreira de. Ensino de português língua estrangeira - PLE - língua global. Revista Virtual de Estudos da Linguagem [ReVEL], v. 2, n. 2, p. 1-8, 2004. [ Links ]

ALTBACH, Philip G. Globalisation and the university: myths and realities in an unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management, Leiden, v. 10, n. 1, p. 3-25, 2004. [ Links ]

BAGNO, Marcos. Do galego ao brasileiro, passando pelo português: crioulização e ideologias linguísticas. In: MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da (Org.). O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. p. 319-338. [ Links ]

BAUMVOL, Laura Knijnik; SARMENTO, Simone. A Internacionalização em Casa e o uso de inglês como meio de instrução. In: BECK, Magali Sperling et al. (Org.). Echoes: further reflections on language and literature. Florianópolis: EdUFSC, 2016. p. 65-82. [ Links ]

BEELEN, Jos; JONES, Elspeth. Redefining Internationalization at Home. In: CURAJ, Adrian et al. (Org.). The European Higher Education Area: between critical reflections and future policies. Cham: Springer, 2015. p. 59-72. [ Links ]

BERBER SARDINHA, Antonio Paulo. Beginning Portuguese corpus linguistics: exploring a corpus to teach Portuguese as a foreign language. Revista D.E.L.T.A., São Paulo, v. 15, n. 2, p. 289-299, 1999. [ Links ]

CÂMARA, Átila Rabelo Tavares. Fluxos migratórios para o Brasil no início do século XXI: respostas institucionais brasileiras. 2014. 111 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Relações Internacionais). Programa de Pós-graduação em Relações Internacionais. Universidade de Brasília. Brasília, 2014. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, Daniela Arguilar; HERMANY, Ricardo. Migração venezuelana e poder local em Roraima. Revista de Estudos Jurídicos UNESP, Franca, v. 22, n. 35, p. 229-251, 2018. [ Links ]

DELL’ISOLA, Regina Lucia Peret; SCARAMUCCI, Matilde Virginia Ricardi; SCHLATTER, Margarete; JÚDICE, Norimar. A avaliação de proficiência em português língua estrangeira: o exame CELPE-Bras. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, Belo Horizonte, v. 3, n. 1, p. 153-184, 2003. [ Links ]

DE WIT, Hans. Internationalization of Higher Education: nine misconceptions. International Higher Education, Chestnut Hill, v. 64, p. 6-7, 2011. [ Links ]

DE WIT, Hans. The future of internationalization of higher education in challenging global contexts. ETD Educação Temática Digital, Campinas, v. 22, n. 3, p. 538-545, 2020. [ Links ]

DE WIT, Hans; HUNTER, Fiona; HOWARD, Laura; EGRON-POLAK, Eva. Internationalisation of Higher Education. (Relatório). Bruxelas: Parlamento Europeu, 2015. [ Links ]

DE WIT, Hans; LEAL, Fernanda; UNANGST, Lisa. Internationalization aimed at global social justice: Brazilian university initiatives to integrate refugees and displaced populations. ETD Educação Temática Digital, Campinas, v. 22, n. 3, p. 567-590, 2020. [ Links ]

FABRÍCIO, Branca Falabella. A “outridade lusófona” em tempos de globalização: identidade cultural como potencial semiótico. In: MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da (Org.). O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. p. 144-168. [ Links ]

FINARDI, Kyria Rebeca; ARCHANJO, Renata. Washback effects of the Science without Borders, English without Borders and Languages without Borders programs in Brazilian language policies and rights. In: SIINER, Maarja; HULT, Francis M.; KUPISCH, Tanja (Org.). Language Policy and Language Acquisition Planning. Cham: Springer, 2018. p. 173-185. [ Links ]

FINARDI, Kyria Rebeca; GUIMARÃES, Felipe Furtado. Internationalization and the Covid-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Opportunities for the Global South. Journal of Education, Teaching and Social Studies, Los Angeles, v. 2, n. 4, p. 1-15, 2020. [ Links ]

FINARDI, Kyria Rebeca; SANTOS, Jane Meri; GUIMARÃES, Felipe Furtado. A Relação entre Línguas Estrangeiras e o Processo de Internacionalização: Evidências da Coordenação de Letramento Internacional de uma Universidade Federal. Interfaces - Brasil/Canadá, São Paulo, v. 16, n. 1, p. 233-255, 2016. [ Links ]

GUALDA, Ricardo. Identidade e discurso em “Avenida Brasil”; “Falar, Ler e Escrever Português” e “Ponto de Encontro”. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, Belo Horizonte, v. 9, n. 2, p. 597-619, 2009. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Felipe Furtado. Internacionalização e Multilinguismo: uma proposta de política linguística para universidades federais. 2020. Tese (Doutorado em Estudos Linguísticos). Programa de Pós-graduação em Linguística. Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. Vitória, 2020. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Felipe Furtado; FINARDI, Kyria Rebeca; CASOTTI, Janayna Bertollo Cozer. Internationalization and language policies in Brazil: what is the relationship? Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, Belo Horizonte, v. 19, n. 2, p. 295-327, 2019. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Felipe Furtado; KREMER, Marcelo. Adopting English as a medium of instruction (EMI) in Brazil and Flanders (Belgium): a comparative study. Ilha do Desterro, Florianópolis, v. 73, n. 1, p. 217-246, 2020. [ Links ]

KNIGHT, Jane. Updating the definition of internationalization. International Higher Education, Chestnut Hill, v. 33, p. 2-3, 2003. [ Links ]

KNIGHT, Jane. Five myths about internationalization. International Higher Education, Chestnut Hill, v. 62, p. 14-15, 2011. [ Links ]

LAGARES, Xoán Carlos. O galego e os limites imprecisos do espaço lusófono. In: MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da (Org.). O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. p. 339-360. [ Links ]

LEAL, Fernanda Geremias. Bases epistemológicas dos discursos dominantes de ‘internacionalização da educação superior’ no Brasil. 2020. Tese (Doutorado em Administração). Programa de Pós-graduação em Administração. Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, 2020. [ Links ]

LEAL, Fernanda Geremias; MORAES, Mário Cesar Barreto. Decolonialidade como epistemologia para o campo teórico da internacionalização da educação superior. Arquivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, Phoenix, v. 26, n. 87, p. 1-25, 2018. [ Links ]

LEITE, Denise; GENRO, Maria Elly Herz. Avaliação e internacionalização da educação superior: quo vadis América Latina. Avaliação, Campinas, v. 17, n. 3, p. 763-785, 2012. [ Links ]

LIMA, Manolita Correia; MARANHÃO, Carolina Machado Saraiva de Albuquerque. O sistema de educação superior mundial: entre a internacionalização ativa e passiva. Avaliação, Campinas, v. 14, n. 3, p. 583-610, 2009. [ Links ]

MIRANDA, José Alberto Antunes; STALLIVIERI, Luciane. Para uma política pública de internacionalização para o ensino superior no Brasil. Avaliação, Campinas, v. 22, n. 3, p. 589-613, 2017. [ Links ]

MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da. O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. [ Links ]

MOROSINI, Marilia Costa; CORTE, Marilene Gabriel Dalla. Teses e realidades no contexto da internacionalização da educação superior no Brasil. Educação em Questão, Natal, v. 56, n. 47, p. 97-120, 2018. [ Links ]

MOROSINI, Marilia; USTÁRROZ, Elisa. Impactos da internacionalização da educação superior na docência universitária: construindo a cidadania global por meio do currículo globalizado e das competências interculturais. Revista Em Aberto, Brasília, v. 29, n. 97, p. 35-46, 2016. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Gilvan Müller de. Um Atlântico ampliado: o português nas políticas linguísticas do século XXI. In: MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da (Org.). O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. p. 53-73. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Milena Yumi. Internacionalização da pós-graduação no Brasil: lógica e mecanismos. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, p. 1-22, 2018. [ Links ]

SALLES, Jerusa Fumagalli de; HOLDERBAUM, Candice Steffen; FINGER, Ingrid. Estudo comparativo do acesso semântico no processamento visual de palavras entre brasileiros monolíngues e chineses multilíngues falantes do português do Brasil como língua estrangeira. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 38, p. 129-144, 2010. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistomologías del Sur. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, Maracaibo, v. 16, n. 54, p. 17-39, 2011. [ Links ]

SIGNORINI, Inês. Política, língua portuguesa e globalização. In: MOITA LOPES, Luiz Paulo da (Org.). O português no século XXI: cenário geopolítico e sociolinguístico. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2013. p. 74-100. [ Links ]

SPOLSKY, Bernard. Language Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [ Links ]

STRECK, Danilo; ABBA, Julieta. Internacionalização da educação superior e herança colonial na América Latina. In: KORSUNSKY, Lionel et al. (Org.). Internacionalización y producción de conocimiento: el aporte de las redes académicas. Buenos Aires: IEC-CONADU, 2018. p. 131-149. [ Links ]

TAQUINI, Reninni; FINARDI, Kyria Rebeca; AMORIM, Gabriel Brito. English as a Medium of Instruction at Turkish state universities. Education and Linguistics Research, Las Vegas, v. 3, n. 2, p. 35-53, 2017. [ Links ]

VAVRUS, Frances; PEKOL, Amy. Critical Internationalization: moving from theory to practice. FIRE - Forum for International Research in Education, Lubbock, v. 2, n. 2, p. 5-21, 2015. [ Links ]

VERTOVEC, Steven. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, Guildford, v. 30, n. 6, p. 1024-1054, 2007. [ Links ]

VERTOVEC, Steven. Talking around super-diversity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, Guildford, v. 42, n. 1, p. 125-139, 2019. [ Links ]

1It is important to notice that, the term ‘Global North’ is a geopolitical term, not geographic, which refers to the centrality/hegemony of certain countries/regions and the knowledge created by them, in relation to the knowledge created in the ‘Global South’, used as a metaphor to describe the geopolitics of the so-called ‘peripheral’ countries.

9In Brazil there is a distinction between interns and scholarship recipients, because interns have their rights and duties regulated by Law n. 11.788 of September 25, 2008 (with a contract up to 2 years), while scholarship recipients usually receive a scholarship without fixed duration, which can be suspended at any time. In the present study we did not include a question to identify the funding agency for scholarships.

10While the questionnaire was being sent to participants, we conducted a quick survey with a representative of SIPLE (The International Society of PFL) and he mentioned that few institutions offer specific courses for educating PFL teachers: UnB, UFBA, Unicamp and UNILA. USP, UFRJ, UFF, UERJ and UFMG (optional or elective courses).

Received: December 01, 2020; Accepted: April 12, 2021; Published: May 05, 2021

texto em

texto em