Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Internacional de Educação Superior

versão On-line ISSN 2446-9424

Rev. Int. Educ. Super. vol.8 Campinas 2022 Epub 12-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.20396/riesup.v8i0.8661980

Article

Andragogy in University Education: The Perception of Undergraduate Professors*

1,2,3Universidade Estadual do Ceará

Andragogy and its assumptions contain fundamental elements for the development of adult teaching and learning, covering specific issues that require attention from educators. In the meantime, this paper aims to understand the perception of undergraduate professors about the importance of Malcolm Knowles' andragogical assumptions. To do this, the following question was raised: “Even though undergraduate professors may not know what Andragogy is specifically, do they perceive its assumptions as important?” We used the mixed methods approach (JOHNSON; ONWUEGBUZIE, 2004), with the application of instruments with a quantitative bias and graphs, and with qualitative analysis. The subjects of this research were 21 professors of higher education in undergraduate courses, responding to an online questionnaire, divided into two sections: questions that addressed the profile of teachers and questions about Andragogy and the degree of importance attributed to the six andragogical assumptions. According to the analysis, it was found that the six assumptions were classified by most of the 21 professors as important / very important with a small portion (two professors, corresponding to 9.5%) that used the “not important” classification. Thus, it is considered that the central questioning of the research, mentioned above, was answered affirmatively. In view of the obtained results, the importance of spreading knowledge about Andragogy and its assumptions is reaffirmed, since it provides professors with greater theoretical foundations and subsidies for their practices, enabling them to reframe their teaching practices.

KEYWORDS: Andragogy; Andragogical assumptions; University education; Undergraduate professor

A Andragogia e seus pressupostos comportam elementos fundamentais ao desenvolvimento do ensino e da aprendizagem de adultos, contemplando questões específicas que requerem atenção por parte dos educadores. Nesse ínterim, no presente artigo objetivou-se compreender a percepção de professores de licenciaturas sobre a importância dos pressupostos andragógicos de Malcolm Knowles. Para isso, partiu-se da seguinte questão: “Os professores de licenciaturas, ainda que possam não saber especificamente o que é Andragogia, percebem como importantes os pressupostos desta?”. Utilizou-se da abordagem de métodos mistos (JOHNSON; ONWUEGBUZIE, 2004), com aplicação de instrumentos de viés quantitativo e elaboração de gráficos, e com análise de cunho qualitativo. Foram sujeitos desta pesquisa 21 professores de nível superior em cursos de licenciaturas, respondentes de um questionário online, dividido em duas seções: questões que abordavam o perfil dos professores; e perguntas sobre a Andragogia e o grau de importância atribuído aos seis pressupostos andragógicos. Conforme análise, verificou-se que os seis pressupostos foram classificados pela maior parte dos 21 professores como importante/muito importante com uma pequena parcela (dois professores, correspondendo a 9,5%) que se utilizou da classificação “pouco importante”. Dessa maneira, considera-se que o questionamento central da pesquisa, supramencionado, foi respondido afirmativamente. À vista dos resultados obtidos, reafirma-se a importância da difusão do conhecimento sobre Andragogia e seus pressupostos, uma vez que proporciona aos professores maior fundamentação teórica e subsídios em suas práticas, possibilitando-lhes ressignificá-las.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Andragogia; Pressupostos andragógicos; Ensino superior; Professores de licenciaturas

La andragogía y sus presupuestos permiten elementos fundamentales para el desarrollo de la enseñanza y del aprendizaje de adultos, contemplando temas específicos que requieren atención por parte de los educadores. Mientras tanto, este artículo tuvo como objetivo comprender la percepción de los profesores de licenciaturas sobre la importancia de los presupuestos andragógicos de Malcolm Knowles. Para eso, se planteó la siguiente cuestión: “Los docentes de los cursos de licenciatura, aunque no sepan específicamente qué es la Andragogía, ¿perciben sus presupuestos como importantes?” Se utilizó el enfoque de métodos mixtos (JOHNSON; ONWUEGBUZIE, 2004), con la aplicación de instrumentos con sesgo cuantitativo y elaboración de gráficos, y con análisis cualitativo. Los sujetos de esta investigación fueron 21 docentes con educación superior en cursos de licenciatura, quienes respondieron un cuestionario en línea, dividido en dos secciones: preguntas que abordaban el perfil de los docentes; y preguntas sobre la andragogía y el grado de importancia atribuido a los seis presupuestos andragógicos. Según el análisis, se verificó que los seis presupuestos fueron clasificados por la mayoría de los 21 docentes como importantes / muy importantes con una pequeña porción (dos docentes, correspondiente al 9,5%) que utilizó la clasificación de “poco importante”. Así, se considera que el cuestionamiento central de la investigación, mencionado anteriormente, fue respondido afirmativamente. A la vista de los resultados obtenidos, se reafirma la importancia de difundir el conocimiento sobre la Andragogía y sus presupuestos, ya que proporciona a los docentes mayores fundamentos teóricos y subsidios en sus prácticas, que les permita replantearlos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Andragogía; Presupuestos andragógicos; Enseñanza superior; Profesores de licenciatura

Introduction

Learning, from the perspective of a set of skills, can always be improved and developed (DeAQUINO, 2007). In this sense, thinking about it in its different contexts and for different subjects is configured as a sine qua non condition given a more democratic education, since access cannot happen disconnected from its forms of realization.

Meanwhile, Andragogy - a word that has Greek origin and comes from 'Andros', from the root ἀνδρ, which means adult man, and the term gogia (agogus/agogos - ἀγωγός), from the root agein (ἄγειν), meaning 'to guide, to lead' (BECK, 2018) - matters as the main theme of this article, in view of our focus on the teaching practice of undergraduate teachers, therefore, of higher education.

To develop this research, we started with the following question: Do undergraduate teachers, even though they may not know specifically what Andragogy is, perceive its assumptions as important? To try to answer this question, we had as a general objective: To understand the perception of undergraduate teachers about the importance of the andragogical assumptions. In turn, the specific objectives were: To investigate the knowledge about Andragogy; to identify, from the answers, the relation of their practice with elements related to Andragogy.

The justification for the development of this research comes from the hypothesis that, even though Andragogy is a relatively new field, as will be better specified during the article, the teachers of higher education, when dealing with adult students, often have actions that are close to issues specific to this field. Therefore, we believe that knowing about Andragogy will make it possible to reaffirm these actions, to re-signify them, to improve them, since it will give them a basis and subsidies in their practice.

The article is divided into the following sections: Introduction; Considerations about Andragogy, containing the subtopics: The Higher Education Student and Andragogical Assumptions; Methodological Procedures; Results and Discussions; and Final Considerations.

Considerations About Andragogy

Andragogy, unlike what is commonly thought, did not appear in 1967, nor was it created by the educator Malcolm Knowles (1913-1997), in the United States. Its origin dates back almost two centuries earlier, in 1833, to the German educator Alexander Kapp (1799-1869), who used the term for the first time, based on the idea that adults learn differently from children. However, the title of "father of Andragogy" is attributed to Knowles, because of his undeniable dedication to research and to the dissemination of its fundamentals, and he was also responsible for presenting the concept to the Americans and, later, to the world.

Andragogy is based on humanistic perspectives, influenced by Rogers and Maslow, and pragmatic perspectives, influenced by Dewey and Lindeman, seeking to focus on the subject's self-realization and experiences, respectively. It is worth mentioning that, unlike Pedagogy, the most popularly known term and science, which focuses on the learning processes of children, Andragogy is characterized as the art and science of helping adults learn (KNOWLES apud DeAQUINO, 2007), focusing on their learning process, This, according to DeAquino (2007) "creates an alignment between this approach and most adults, who seek independence and responsibility for what they believe is important to learn.

The point here is not to make a simple comparison between Pedagogy and Andragogy, much less place them in antagonistic positions, since we do not consider them as parts of a dichotomous relationship, since one does not annul the other, on the contrary, they complement each other. Knowles' perspective, when referring to the pedagogical model as a model that gives the teacher total control over the decision-making process of the child's learning, which has a submissive role, portrays, in fact, the context of his time.

In this regard, it is worth noting that the pedagogical and andragogical models were presented in the first edition of Knowles' writings, in 1980, in a way that denoted opposition between the two, but the author himself later reviewed issues of this nature (KNOWLES; HOLTON; SWANSON, 2011). The author also acknowledged, in his autobiography in 1989, that he no longer saw Andragogy as a complete theory: "I prefer to see it as a model of hypotheses about adult learning or a conceptual framework that serves as a basis for emerging theories" (KNOWLES, 1989, p. 112 apud KNOWLES; HOLTON; SWANSON, 2011, p.156). We will discuss the andragogical hypotheses in Section 2.3.

In an andragogical perspective, the student is an assiduous participant in his learning process, based on exchanges with his teacher, who plays the role of facilitator of this process. Knowles asserts that the educator who makes use of Andragogy in a learning situation with adults will spare no effort to provide his student with the basis and then stimulate him to develop greater autonomy in the process (KNOWLES, 1979 apud KNOWLES; HOLTON; SWANSON, 2011). The cited authors further explain that:

Adult learning occurs in a variety of settings for a variety of reasons. Andragogy is a transactional model of adult learning developed to transcend specific applications and situations. Adult education is just one field of application in which adult learning occurs. Others could include human resource organizational development, secondary education, or any other field in which adult learning exists (KNOWLES; HOLTON; SWANSON, 2011, p.135-136).

Furthermore, in view of the above, in this article we will focus on a specific type of adult learner, which is the upper level student, to be better specified in the following topic.

The Higher Education Student

Something that should be considered a priori, when talking about Andragogy, is the adult student. We know that autonomy is not an absolute rule at any age, although the idea that there is a period for its development is common, as shown by Piaget (1994) in his theory of Moral Development. When dealing with a student that reaches the higher level, often driven by circumstances, it is important to get to know him and dialogue with him, an act that, from Paulo Freire's (2011) perspective, is not possible in a vertical relationship between student and teacher, since it aims at a meeting of equals. In this sense, the teacher is also a learner and, thus, education in diverse spaces becomes possible.

In his book "How to Learn: Andragogy and Learning Skills", Carlos Tasso Eira De Aquino (2007) states that one of the problems adults face in their learning is because "they were taught to learn in a pedagogical way" (p. 4) and that the student who leaves high school leaves with this kind of learning. This statement leads us to infer that, although it cannot be quantified in exact data, since there was no scientific research on our part to do so, a large portion of students who start at the higher level do not have an autonomous posture in relation to their learning process.

The author in question brings a brief real portrait of who the students that arrive at higher education really are: ordinary people who are disguised as experienced adults and free of anxieties, desires, according to the eyes of social expectations, of the projections that society throws at these students. It is worth pointing out, an important conjunction in the context of this article, that when it comes to institutions located in municipalities of greater need, it is common the presence of students who not only are not part of this tiny range of "well-off", but are still on the threshold of their development as autonomous subjects, since the conditions that lead them to their respective courses are dependent on factors of all kinds, for example, infrastructure.

Considering the variety of origins and backgrounds of students entering or returning to higher education, DeAquino (2007) explains the importance for educators to know these subjects and suggests a Form that identifies the student profile that contemplates both their personal characteristics and their concerns with studying at this level of education, which, according to the author, would help the teacher in the choice of his techniques. After using this form for three years, with more than 350 higher level students, including even graduate students, the author concluded some of the main aspects to be closely observed by the teacher, among them:

Lack of confidence; Unawareness of resources available to facilitate learning; Lack of clarity in the reasons for studying or returning to study; Little or no development of learning skills; Unawareness of learning styles; Lack of a bolder, more proactive learning stance; Lack of progress records; Lack of progress; Lack of good time management (DeAQUINO, 2007, p. 66).

We brought the example of this form developed by DeAquino (2007) and the result of his respective research specifically to support the breaking of the stereotype of the "well-resolved" higher education student made by the author himself. In this direction, it is important, as teachers of these students, to consider the peculiarities of each experience brought by these subjects, of each context, since teaching, therefore, requires respect for the knowledge of these subjects (FREIRE, 2012).

Therefore, and as an example, DeAquino (2007) tells us about the importance of reflecting with the student about the reasons that led him to college, his return or choice to a certain course. This helps him to maintain his enthusiasm in times of personal crisis. We would add that, more than that, and considering the locus of the courses we bring here (campuses in the interior of the state of Ceará), this action also helps the student to re-signify or even find reasons that satisfy him, in some way, in his learning process, helping him to remain firm in his choice and in his academic journey. The author then suggests a list of reasons for the students to mark, in an attempt to stimulate this reflection.

Certainly, we will not go into this merit in order not to escape the scope of this article, but by bringing examples of DeAquino's suggestions, we do want to show that there are possibilities of action by teachers who propose to support adult students, as long as they look at them from multiple points of view, to pay attention to their specificities. A starting point for this is the knowledge of the andragogical assumptions created by Knowles (1980), which we will explain in the following topic.

Andragogical Assumptions

According to the ideas of Knowles (1980 apud Knowles, Holton and Swanson, 2011). there are six fundamental assumptions/principles or hypotheses1 of Andragogy, as shown in the chart below, two of which have been added over time (assumptions 1 and 6 - indicated by pink color). Knowles, Holton, and Swanson (2011) state that many authors draw on Knowles' ideas, although there is some variation in the definitions of his assumptions.

Table 1 The presuppositions/principles/hypotheses of Knowles

| FUNDAMENTAL ANDRAGOGICAL ASSUMPTIONS |

|---|

| 1 - NEED TO KNOW |

| 2 - THE LEARNER'S SELF-CONCEPT (SELF-DIRECTION) |

| 3 - LEARNER'S EXPERIENCE |

| 4 - READINESS TO LEARN (DAILY TASKS) |

| 5 - LEARNING ORIENTATION (PROBLEM FOCUS) |

| 6 - MOTIVATION TO LEARN (INTERNAL) |

Source: The authors.

These andragogical assumptions do not have a prescriptive character, which must be followed meticulously, but rather an adjustable character. In this sense, it does not mean that all teachers of adult learners should apply them indiscriminately, but, on the contrary, seek to adapt them according to the situations and contexts, since, as evidenced by Knowles himself (1984b apud Knowles, Holton and Swanson, 2011) Andragogy has as an indispensable characteristic, precisely flexibility.

Assumption number 1, 'Need to know', was one of the assumptions inserted into the set later and concerns the value of the adult learner being an active part of their learning process. The adult when engaged as a "collaborative partner" in this process satisfies this need, as well as instilling their self-knowledge, their independence (KNOWLES; HOLTON; SWANSON, 2011, p. 176). This principle is based on the "how", "what", and "why" learning questions.

Assumption 2, 'Learner Self-Concept', refers to the premise that the adult learner is self-directed, therefore "tends toward the self-concept of being responsible for his decisions" (SOBOLL, 2010, p.4) for his actions, his learning, being, in this way, conscious of his actions and capable of self-management. The adult learner, in this perspective, sometimes offers resistance to the imposition of other people's wills.

Assumption 3, 'Experience of the apprentice', takes into account the fact that adults accumulate a wide range of experiences, and that they carry a great deal of experience. In this sense, the experience that the adult student carries with him has an important value for his learning, intensely influencing the way he learns.

Regarding Assumption 4, 'Readiness to learn', Knowles, Holton and Swanson, (2011, p. 185-186) state that "adults generally become ready to learn when the life situation creates a need to know", that is, to the extent that they understand the effective usefulness of that content for their lives. This is because adults "have a more pragmatic orientation" (SOBOLL, 2010, p.5-6), seeking to learn what is most instantly relevant to their lives.

Assumption 5, 'Learning orientation', concerns the premise that the adult learner is centered on life and its practical problems, with this, they seek learning as solving these problems, as they "learn best when new information is presented in real-life contexts" (KNOWLES, HOLTON, SWANSON, 2011, p.188).

Finally, in assumption number 6, 'Motivation to learn', also characterized by the pink color in the table, not far from the aforementioned assumptions, brings the idea that the adult is more motivated to learn what has validity for his real life or what will provide him with gains. These gains have more weight, according to Knowles, when they are internal, for example, personal satisfaction. Gains that are external to the individual, such as a promotion at work or a salary increase, are also important, but are of secondary importance.

In view of these assumptions it is worth noting that, as Knowles, Holton, and Swanson (2011, p.194) assert:

Learning is a complex phenomenon that defies description by any single model. The challenge has been - and continues to be - to define what is most characteristic among adult learners, to establish the fundamental principles, and to define how to adapt them to varying circumstances. The more researchers identify factors that operate the moderation and mediation of adult learning, the more solid the core principles become.

Thus, we emphasize that, although the andragogical assumptions are not something that can be simply applied, disregarding the contexts and specificities we have been emphasizing, they are a fundamental basis for the education of higher education students and tend to become stronger as they are known, considered, and reflected upon by the teachers who deal with these students. We corroborate, then, with the aforementioned authors when they say that "from this perspective, there is no reason to expect all adults to behave in the same way, but rather that our understanding of individual differences will help shape and adapt the andragogical approach to suit the uniqueness of the learners" (p.145).

Methodological Procedures

The present research has a mixed approach (JOHNSON; ONWUEGBUZIE, 2004), considering that we used elements of both the quantitative approach, with the application of a quantitative bias analysis instrument and the preparation of graphics and the qualitative approach, for the analysis of responses and graphics.

According to Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004, p.21), the mixed approach "can answer a broader and more complete range of research questions because the researcher is not confined to a single method or approach". This approach can also function as a "third research paradigm" (p.2), enabling benefits in research in all areas, but primarily in the field of education, given the wide range of topics covered by them.

The data collection occurred through the application of an online questionnaire, prepared on the Google platform, with Google Forms, which could be answered in an average time of seven minutes. Initially, we prepared a questionnaire containing 10 questions, the first two of which referred to the profile of the respondents (academic background and teaching time in undergraduate courses) and the others, in general, were about Andragogy and its assumptions. In this sense, the questionnaire was divided into two sections, the first composed of questions about the profile of teachers, and the second composed of questions about Andragogy and the degree of importance assigned to the six andragogical assumptions.

The criterion for the choice of subjects was to be an upper-level teacher in undergraduate courses at the Federal Institute of Ceará (IFCE), in view of the empirical approximations of the main author of this work with the undergraduate courses of that institution, from her experiences as a substitute teacher at the institution, in the period from 2018 to early 2020. The contact with students of undergraduate courses from communities, sometimes deprived, aroused the desire to approach other professionals from the various campuses of the institution, in order to understand their perceptions of certain concepts and situations, as mentioned above, based on their work in the undergraduate courses in question.

The questionnaire was sent to 30 professors, 21 of whom answered, working in different campuses of the institute, namely: Camocim, Limoeiro do Norte, Itapipoca, Umirim, Tauá. The degrees in which these subjects teach also vary between Portuguese-English Letters, Chemistry, Physics, Music, Physical Education. Participation was voluntary and we guaranteed the anonymity of the participants based on the norms that govern research in the Human and Social Sciences, developed with human beings, safeguarded by Resolution No. 510/2016.

For better visualization of the answers, we will present most of them in graphs, to be analyzed in the following topic.

Results and Discussion

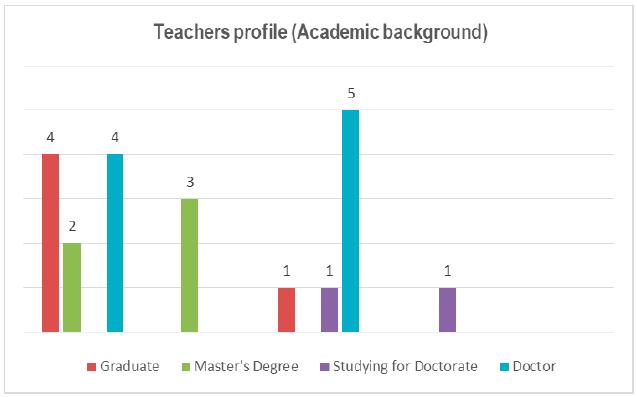

In this topic, we will present the results of what we obtained with the questionnaire applied to the teachers, as well as some considerations about the data that will be presented. To facilitate the reader's understanding, in addition to the graphic display, we will indicate the values in percentages. In summary, the profile of the respondents is shown in Graph 1 below:

As observed, of the 21 teachers participating in the survey, five have only undergraduate degrees (Letters and Physics), six have master's degrees (Letters and Pedagogy), two teachers are pursuing doctoral degrees (Physics and Physical Education), and nine teachers have doctoral degrees (Letters and Physics).

Regarding the time, they have been teaching undergraduate courses, seven teachers answered that they have been teaching between one and three years, another seven answered that they have been teaching between three and five years, and the remaining seven said they have more than five years (= 33.3% each).

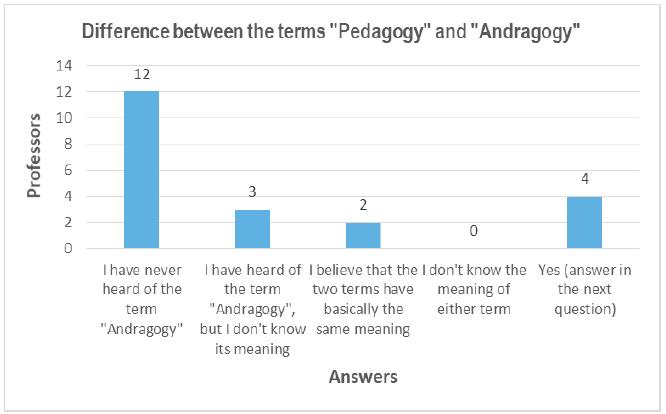

After identifying the formation and teaching time of the teachers at the higher education level, we thought it would be interesting to ask them if they knew the difference between the terms "Pedagogy" and "Andragogy", before effectively asking them about the importance they gave to situations that illustrated the andragogical assumptions of Knowles (1980).

As can be seen from the analysis of Graph 2, of the 21 respondents, 12 have never heard of the term 'Andragogy'; three have heard of it, but do not know the meaning of the term; another two believe that both terms have the same meaning.

Source: The authors.

Graph 2 Question regarding the difference between the terms 'Pedagogy' and 'Andragogy

The other 4 respondents marked the option that they knew the difference between the terms, explaining it in the next question of the questionnaire, whose answers, in general and in a few words, said that the difference was that Pedagogy is teaching/education with children and Andragogy is teaching/education with adults/aimed at adults. A slightly more detailed answer said, in addition to what was said in the other answers, that Pedagogy "has the teacher at the top of the process". We emphasize here that the detailing to which we refer concerns only the comparison we made to the other answers, since the respondent expresses, in his meager definition, some of the initial antagonistic conceptions of Knowles' writings, as mentioned above, in topic 2.1.

It is worth noting that, different from what we imagined, the initial educations of the subjects were not determinant in their knowledge of the meaning of Andragogy. Both teachers with degrees in Pedagogy and Languages (courses recognized by the wide discussions) said they had never heard of the term, and, on the other hand, teachers with degrees in more exact areas (Physics) proved to be initiated in the subject. As far as the importance given to situations associated with the andragogical assumptions is concerned, let's analyze Graph 3:

Source: The authors.

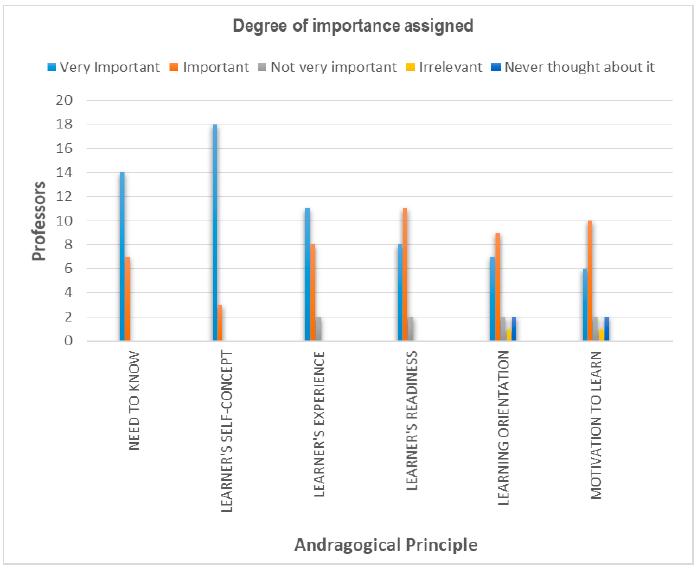

Graph 3: Summary of the answers to the six questions about the six andragogical assumptions.

Graph 3 is the result of six questions, each referring to an andragogical principle, in which we sought to know the degree of importance attributed by the teacher to situations that illustrated these assumptions.

In the question referring to principle 1 'Need to know', we asked the teachers about the importance of the student knowing the 'what', the 'why', and the 'how' he/she will/should learn a certain content. 14 teachers answered that it is very important, and seven answered that it is important (respectively 66.7% and 33.3% of the teachers). The question related to principle 2 'Self-concept of the learner', dealt with the importance of the student being aware of his responsibility in learning and having the ability to self-manage, to which the vast majority answered that it is very important (18 teachers = 85.7%) and the minority (three teachers = 14.3%) answered that it is important.

In turn, for principle 3 'Experience of the learner', a question was generated about the importance teachers attached to the fact that the student's life experiences were considered in the learning process. In response: 11 teachers considered it very important (= 52.4%), eight considered it important (= 38.1%) and two not very important (=9.5%).

Regarding principle 4 'Learner readiness', we sought to find out from the teachers the importance of the student's learning being related to life, thus understanding the usefulness of what they are learning. Eleven teachers consider it somewhat important (= 52.4%), eight consider it very important (= 38.1%), and only two consider it of little importance (=9.5%).

Principle 5 'Learning orientation' was illustrated by the question regarding the relevance of the student's learning being contextualized, focused on the problem, not merely on the content, to which seven teachers considered it to be very important (= 33.3%,), nine said it was important (= 42.9%,), two thought it was not very important (= 9.5%), another two said they had never thought about it (= 9.5%), and only one teacher (corresponding to 4.8%) considered it irrelevant.

Finally, in principle 6, "motivation to learn", the question about the relevance of the adult student having his motivations considered/understood, such as professional/salary promotion, self-esteem, satisfaction, and quality of life: six teachers consider it to be something of great importance (= 28.6%), 10 answered that it is something important (= 47.6%), two say it is something not very important (= 9.5%), other two affirm that they have never thought about it (= 9.5%), and one teacher considers it to be something irrelevant (= 4.8%).

What we conclude from the above chart is that, of the six andragogical assumptions, the teachers' ranking in degree of importance varies a little more only in those concerning 'Orientation to learning' and 'Motivation to learn', which had one "irrelevant" consideration, and two "never thought about it", which, in view of the overall, is a small amount, since the vast majority consider the presented situations/assumptions to be of an important/very important character for the learning of their undergraduate students. However, we should also consider that of the six assumptions, only 'Need to know' and 'Learner's self-concept' were not classified by any of the respondents as "not very important".

However, some considerations should be made in order to favor an authentic interpretation of the analysis: i) Each of the questions in the questionnaire was directly related to its respective principle, according to the definition presented in topic 2.3, based on Knowles' writings. We did not ask the teachers directly about the importance they gave to the andragogical assumptions, considering that, possibly, not all teachers would know about their existence, since, as mentioned before, the term Andragogy is not so widely known yet; ii) We must keep in mind that the teachers' answers, although we can associate them to similar cases, refer to the possible and satisfactory sample of subjects for the scope of this article.

We also consider it relevant to highlight the speech of one of the research respondents in the space in the questionnaire designated for free considerations by the participants:

In some items I marked the option important and not very important because of the scale used in the questions. As I deal directly with undergraduate degrees in exact sciences I see great difficulty of students in more technical subjects (reading, text interpretation, treatment of simple mathematical expressions). Many times this knowledge is necessary in order to develop ideas and concepts that are more in tune with daily life (contextualized). Sometimes I see it as necessary to "sacrifice" part of what I consider important in the contextualization of certain problems in order to promote the solidification of this "technical knowledge". This is a view I have had with most of the last few classes I have dealt with. I think it's important to make this clear (Professor PhD in Physics).

In other words, the teacher expresses that, despite assigning a high degree of importance to certain situations (illustrating the andragogical assumptions), sometimes he needs, in his words, to "sacrifice" what he knows to be relevant for the student, in order to have greater conditions (we can think of his time in the classroom, for example) to focus on other issues also relevant for the student's development, related to his area of expertise.

We consider the teacher's comment to be of great value, since it reminds us of what we have previously clarified, based on the concept of Knowles himself (1984b), that the assumptions, although relevant, are not recipes, considering that each situation is unique. Furthermore, looking at more general facts of education, within the conditions presented earlier (topic 2.2 - The student at the higher education level), the level of students who reach the higher education level does not always match expectations. Given this, various factors must certainly be considered, among them the quality of the supply and conditions of basic education itself, from which the higher education student emerges, but which are beyond the scope of this article.

Therefore, the teacher is always the subject that, despite all the attributions that are already placed upon him/her, tries to balance between the obstacles that are placed in the learning process of his/her students. In view of this, we reaffirm that knowing about Andragogy will make it possible to reaffirm their actions, resignify them, improve them since it will give them a basis and subsidies in their practice.

Final Considerations

In this research, starting from an initial question - "Do undergraduate teachers, even though they may not know specifically what Andragogy is, perceive its assumptions as important?" - we set out to understand the perception of undergraduate teachers about the importance of the andragogical assumptions and, for this, to investigate their knowledge about Andragogy, as well as to identify, from the answers, the relationship of their practice with elements related to Andragogy.

We had as justification for the development of this research the hypothesis that even though it is a relatively new field, the Andragogy is present in the practice and conception of higher education teachers, therefore, knowing more about the theme makes it possible to reaffirm, re-signify and improve this practice, as they will have a greater understanding of issues specific to the universe of this field.

As explained in more detail in topic 4 (Results and Discussion), in general, the six andragogical assumptions were classified by most of the 21 teachers as important/very important. Only one teacher used the classification "irrelevant", and two used the classification "never thought about it", in the situations referring to the assumptions "learning orientation" and "motivation to learn". Although in four assumptions two classifications of "not very important" appeared, given the value that this number means (9.5%), we consider that our hypothesis was confirmed and our question was answered affirmatively.

In view of this, we admit that this research can be useful in promoting the debate about the andragogical assumptions in the teaching environment of undergraduate courses, in order to reflect on its importance in the learning process of the student at the higher education level. Therefore, we reaffirm the importance of spreading the knowledge about Andragogy and its assumptions, in order to raise reflection about them, promoting improvements in the teachers' practice.

REFERENCES

BECK, Caio. A origem do termo Andragogia. Andragogia Brasil. 2018. Disponível em: https://andragogiabrasil.com.br/a-origem-do-termo-andragogia/. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

CONSELHO NACIONAL DE SAÚDE. (2016).Resolução nº 510/2016. Disponível em: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2016/Reso510.pdf Acesso em: 20 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

De AQUINO, Carlos Tasso Eira. Como aprender: Andragogia e as habilidades de aprendizagem. 1ª edição, São Paulo Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.160 p. ISBN-13 : 978-8576051589 [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa. 10ª edição, São Paulo: Paz & Terra, 2012. 240 p. ISBN-13:978-8577531868 [ Links ]

JOHNSON, R. Burke.; ONWEGBUZIE, Anthony John. A Mixed Methods Research: A research paradigm whose time has come, Educational Researcher, Vol. 33, nº. 7, 2004, p. 14-26. Disponível em: http://sites.uci.edu/socscihonors/files/2017/09/Mixed_Methods_Research.pdf Acesso em: 10 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

KNOWLES, Malcom Shepherd. HOLTON III, Elwood F. SWANSON, Richard A. Aprendizagem de Resultados: Uma Abordagem Prática para Aumentar a Efetividade da Educação Corporativa. 2ª edição. Tradução de Sabine Alexandra Holler. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2011. Recurso digital. ISBN 978-85-352-4928-6 [ Links ]

PIAGET, Jean. O Juízo Moral na Criança. 4ª edição, São Paulo: Summus Editorial, 1994. 304 p. ISBN-13:978-8532304575 [ Links ]

SOBOLL, Renate Stephanes. Metodologia andragógica e docência transdisciplinar na educação à distância. In: 16º CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO à DISTÂNCIA. 2010, Paraná. Anais do 16º CIAED Congresso Internacional ABED de Educação a Distância. Cd. ISBN: 2175-4098. Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná: Associação Brasileira de Educação a Distância. Disponível em: http://www.abed.org.br/congresso2010/cd/252010184616.pdf Acesso em: 16 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

Received: November 07, 2020; Accepted: December 05, 2021; Published: January 19, 2022

texto em

texto em