Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Internacional de Educação Superior

versão On-line ISSN 2446-9424

Rev. Int. Educ. Super. vol.8 Campinas 2022 Epub 12-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.20396/riesup.v8i0.8663729

Research Article

The Professional Action of the University Pedagogical Advisor (UPA): Dialogues About his Career in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay*

1,2Universidade Estadual Paulista

This article aims to understand the trajectory and professional performance of university pedagogical advisors, from an investigation of qualitative research approach, of an exploratory nature, which uses the multiple case study method, with data analyzed through content analysis. Advisors of four universities were investigated, being two in Brazil, one in Argentina and one in Uruguay, whose data were collected between 2018 and 2019. The analysis indicates that the advisor's professionalism is in development, however, there are countless challenges that they need to overcome, such as the lack of autonomy, institutional support, legitimacy in the function and the pedagogical training of university teachers. We conclude that, related to the development of their professionalism and the overcoming these challenges, specific professional knowledge of the university pedagogical advisor is necessary, which, if developed, can help to reach their professional legitimacy.

KEYWORDS: University pedagogical Advisor; University pedagogy; Profissionalization; Teacher education; Knowledge

O presente artigo objetiva compreender a trajetória e a atuação profissional dos assessores pedagógicos universitários, a partir de uma investigação de abordagem qualitativa, de cunho exploratório, que se utilizou do método de estudo de caso múltiplo, com dados analisados por meio da análise de conteúdo. Foram investigados assessores de quatro universidades, sendo duas no Brasil, uma na Argentina e uma no Uruguai, cujos dados foram coletados entre 2018 e 2019. A análise indica que a profissionalidade do assessor está em desenvolvimento, no entanto, há inúmeros desafios que ele precisa superar, como a falta de autonomia, apoio institucional, legitimidade na função e a formação pedagógica do docente universitário. Concluímos que, relacionados ao desenvolvimento de sua profissionalidade e à superação dos ditos desafios, são necessários saberes profissionais específicos do assessor pedagógico universitário que, se desenvolvidos, podem auxiliar para o alcance de sua legitimidade profissional.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Assessor pedagógico universitário; Pedagogia universitária; Profissionalização; Formação docente; Saberes

Este artículo tiene como objetivo comprender la trayectoria y desempeño profesional de los asesores pedagógicos universitarios, a partir de una investigación con enfoque cualitativa, de carácter exploratorio, que utilizó el método de estudio de casos múltiples, con datos analizados mediante análisis de contenido. Se investigaron asesores de cuatro universidades, dos en Brasil, uno en Argentina y uno en Uruguay, cuyos datos fueron recolectados entre 2018 y 2019. El análisis indica que la profesionalidad del asesor está en desarrollo, sin embargo, son numerosos los desafíos que necesita superar como la falta de autonomía, apoyo institucional, legitimidad en la función y la formación pedagógica del docente universitario. Concluimos que, relacionado con el desarrollo de su profesionalidad y la superación de estos desafíos, es necesario un conocimiento profesional específico del asesor pedagógico universitario, que de ser desarrollado puede ayudar a alcanzar su legitimidad profesional.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Asesor pedagógico universitario; Pedagogía universitaria; Profesionalización; Formación de docentes; Conocimiento

Introduction

The researches that have been done within the field of University Pedagogy, supported mainly in publications by Cunha (2006a; 2006b; 2008; 2010; 2014) and Lucarelli (2000; 2004; 2008; 2015) demonstrate that the debate on University Pedagogical Advisory Services in Brazil is still a challenging issue, mostly because there is not, at least in public universities, a function that officially has this name. Therefore resulting in a lack of identification between the people who exercise the advisory function at universities and the nomenclature used in the cientific literature by researchers of the field.

The studies have shown a that the university pedagogical advisor is one of the professionals concerned with the subject of University Pedagogy (UP), a polysemic field of production and application of pedagogical knowledge in higher education, within the scope of higher education institutions (HEI). Thus, it is important to emphasize that the term university pedagogical advisor (UPA) was been used throughout this work to designate all those who exercise pedagogical functions in higher education, with the purpose of bringing it to the center of discussions.

University Pedagogy, at first, had as its main concern “to understand the institutional strategies aimed at the professional development of teachers in the context of the democratization, expansion and interiorization of brazilian higher education” (CUNHA, 2014, p. 55). However, with the events of recent years and the increase in the scrapping of the public university, the commodification of education, the discourses of devaluation of public education, other concerns have arisen in the field, greatly interfering in the pedagogical processes of universities. Lucarelli (2000) emphasizes that the UP is field of “connection of knowledge, subjectivities and culture, which demands contents that are highly specialized scientific, technological or artistic oriented to the formation of a profession” (LUCARELLI, 2000, p. 36). Thus, everything that relates to the pedagogical processes within the HEI, in the scope of research, teaching or extension, is the focus of the field of University Pedagogy.

However, even though the UP knowledge is fundamental for the educational processes that take place in higher education, as well as for the performance of the (UPA), this function is still little known or valued in Brazil, unlike what happens in Argentina and Uruguay. This statement can be proved in any light conversation with students, teachers and even with professionals who carry out pedagogical advice at universities. This reality means that many people who work professionally in University Pedagogical Advisories do not identify themselves as UPAs, which sometimes makes them not familiar with the reference used here, reinforcing the lack of identification with the research produced in the field.

Thus, this article contributes to the discussion with the objective of understanding the trajectory and professional performance of university pedagogical advisors by placing the UPA in the university context, reinforcing the name of its professionals position, clarifying its functions and actions. Apropos, the thesis that fundament this work proposes to question how the professional action of the individual who performs the role of pedagogical advisor at the university has occurred, aiming to understand his professional trajectory and performance in the exercise of the function.

This question guided the methodological path that led to a closer look at the work developed by advisors from two Brazilian federal universities and two institutions outside the country, one in Argentina and the other in Uruguay. These paths helped in the reflection about the professional construction of the UPA, its performance as a professional, its relevance, its limitations, but especially its possibilities. These realities, which produce cultures and their own professional demands, allow looking at the advisor's professional trajectory from different angles, leading to a panoramic view of the construction of such a young and little recognized duty.

Pedagogical Advisor in Universities

The university pedagogical advisor is a character present in many higher education institutions in Brazil and other countries, but usually does not have much visibility because they are neither teachers nor managers. However, despite this low visibility, when the figure of the advisor is foreseen in the institution, most of the time, this individual is involved in many tasks, among them the planning, discussions and actions that can help to improve the pedagogical processes that surround the university. In this way, a professional with still little or none recognition, especially in Brazil, has shown, through research carried out in loco, to be a presence whose importance in the universities has been increasing, as he has, in the midst of his functions, the task to motivate training courses capable of interfering in the quality and progress of pedagogical issues, especially in undergraduate education (CARRASCO, 2016).

Among the researchers who investigate the university pedagogical advisor is Lucarelli, an Argentine researcher who points out that their professional action is mostly dedicated to help. According to this researcher,

University Pedagogical Advisory [...] is recognized as a helping profession in an environment in which intervention practices are oriented towards achieving changes that affect the educational institution as a whole and the classroom in particular. [...] as a helping profession, it manifests and requires an evaluative theoretical framework that allows understanding and justifying the development of this practice at the university (LUCARELLI, 2008, p. 4).

Tasks focused on pedagogical issues involving teaching, research and extension require those professionals constantly try to establish partnerships in their work. This premise, combined with Lucarelli's understanding of a helping profession (2008), favors a sense of partnership and collaboration, breaking with the feeling of superiority that can be established in any of the parties involved in pedagogical relationships, in other words, between professors, advisors and other university professionals.

The Encyclopedia of University Pedagogy, produced by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP) and by the Southern Brazilian Network of Higher Education Investigators (RIES), with Morosini (2006) as editor-in-chief, highlights as one of its entries the advisory pedagogical. It defines pedagogical advice as

intentional action of monitoring and supporting the pedagogical processes produced in scholar and non-scholar spaces. For some authors, it is a specialized practice in a situation that requires the definition of values and an explicit theoretical framework (NICASTRO and ANDRÉOZZI, 2003). Notes: Pedagogical advice has been understood as a political and institutional action, and for that, it has being linked to historical periods and specific pedagogical projects, and can represent an oscillation between the regulatory and emancipatory functions. On the first perspective, its function is to guarantee the achievement of objectives in a rationality of effectiveness and efficiency; on a second look, it proposes to support the movements of construction of the autonomy of the subjects involved with pedagogical processes (CUNHA, 2006b, p. 383, author's emphasis).

Another researcher who has been dedicated to the field of University Pedagogy is Cunha (2006a, 2006b, 2008, 2010, 2013, and 2014) and many of her works deal with the role of pedagogical advice on universities. As stated in the entry presented on the quote above, since UPA is an act with intentional follow-up and support, it will necessarily be a political action that will require choices. That being so, Cunha (2006b) shows that training processes, in fact, require opening up and creating possibilities for the construction of autonomy of the subjects who are inserted on the context. The UPA is, in this logic, a beginning for training processes, so that it is not possible to talk about the advisor's action without reflecting on higher educational teaching.

Teaching, as the highly complex activity that it is, requires a specific professional construction based on a specific professional knowledge. However, in higher education, the path in which the individual begins to teach can make this professional construction unfeasible. This affirmation is based on the fact that the academic journey of these individuals is much more focused on research than teaching, and because of that, the teaching profession in higher education ends up being built in practice - which may not bad -, demanding a reflexive movement, necessary to construct an identity as teacher that may not happen. Even though, this movement is necessary so that there are advances in classroom practices with students, and the reflection that leads to it can be triggered by the UPA, which has as one of its functions to promote the pedagogical training of university professors.

In this direction, Cunha (2014) emphasizes the importance of developing teaching knowledge, in order to better articulate theory and practice in the continuing education of university professors. Thus, among the advisors' responsibilities, according to researches carried out, the one that most challenges the professional advisors is the one related to the pedagogical training of university professors. In this perspective, Cunha (2014) affirms the importance of strategies that ensure that training does not fall into specific moments that do not identify with the idea of professional development, as they do not offer the action - reflection - action movement (CARRASCO, 2016). This is the premise on which this research is based, assuming that teacher training is materialized on the reflection over shared actions, and not only on a solitary one, but also understanding that this training process is directed to the advisor himself, who needs to be trained in action and in the reflection on action, sharing what you have done and experienced.

Thus, in relation to this training function of the UPA, one of the challenges to be overcome is the instrumental aspect of the training processes that often accompany the proposals regarding this action with university professors, since the complexity of teaching can lead the advisor to assume a proposal immediatist training, offering, among its proposals, those that would apparently promote rapid changes in teachers' practice and, consequently, also rapid results in student learning. Regarding this, Cunha (2014) warns that the dynamics of permanent pedagogical training, based on a conception of constructing knowledge and on the rupture with a pragmatic and immediatist understanding of pedagogical prescriptions, will hardly happen spontaneously, requiring, in order to be effective, “ an institutional movement of stimulus and support to shelter reflection [...], [in which] the process will be much more significant when shared with peers, understanding that collective spaces are producers of cultures where teaching knowledge is established” ( CUNHA, 2014, p. 37, emphasis added). The institutional stimulus and support, therefore, must emerge exactly from the Pedagogical Advisories, understanding, however, that it is not a job of one person (CUNHA, 2014).

Along with this understanding, Hevia (2004) classifies the role of the pedagogical advisor as complex for several reasons and one of them is, exactly, the need to establish partnerships. Considering that the UPA needs to liaise with many components of the higher educational institutions, from the management members, to discuss planning issues, legal decisions and training proposals to the professors and technicians involved in the pedagogical processes, it is possible to assimilate the complexity. Also according to the author, allied to this is the diversity of requirements related to institutional issues and the formative role of the advisor, which needs to be carried out in this context. In Brazil, it is common for pedagogical advice to find itself in an amalgam of functions, losing much of its focus, which is pedagogical and formative, in the midst of exclusively administrative functions. Broilo (2015) warns that “the credibility of the pedagogical sectors needs to be conquered and their actions and conceptions must be transformed” (BROILO, 2015, p. 51), in other words, it is not enough just to have a pedagogical sector and advisors who work in it; it is also necessary to deal with a constant struggle for legitimate their functions that can only be won with through well-founded and articulated work.

Xavier (2019), after mapping 19 Brazilian universities that joined the REUNI and the Interdisciplinary Baccalaureate curriculum model, delimits the responsibilities of the Pedagogical Advisory in five dimensions. This limitation of the functions of university pedagogical advising aims to the help so that the UPA’S work does not get lost. The author defines these dimensions of UPA responsibilities as:

a) Advising professors: responsibility that involves all assistance related to didacticpedagogical issues, which include teaching and lecturing university classes, in order to constitute a space for consultation and support, whether individual, to meet specific demands, whether collective, to meet multi or interdisciplinary demands of teams in certain areas of knowledge.

b) Advice on teaching professional development: responsibility aimed at carrying out actions that allow the permanent growth of teachers in their careers, in terms of acquiring knowledge and mastering skills related to teaching. It refers to training actions, planned and systematized, in all dimensions that concern the knowledge of the teaching profession, which must be developed with continuity, intentionality, through institutional programs, in collective training spaces that value and are based on the teaching learning, based on their different epistemological cultures.

c) Advice on institutional evaluation: responsibility that is linked to management bodies, but also to educational practice as a whole. Assumed as an institutional structure with a large scope of work, the advice to institutional evaluation highlights the strengths and also the gaps to be solved in the pedagogical field, taking as a reference the vision of the entire academic community, opening opportunities to resize these evaluated issues.

d) Curriculum advising: responsibility regarding issues of planning and development of curricula, pedagogical projects, whether courses or institutional, as well as teaching plans. It contemplates, the normative-legal knowledge that encompasses the professional careers, regarding the academic formation, and the epistemology of the different fields of knowledge. It is an action that supports the pedagogical decisions of teachers, in collegiate groups, leading discussions and transformations in the projects and, consequently, in the conceptions and practices about teaching, research and extension, innovation, entrepreneurship, interinstitutional partnerships, and their intrinsic relationships.

e) Student orientation: responsibility that takes place with another actor in the teaching and learning process, one without which coherent solutions and interventions for the academic questions cannot be determined. When supporting students, on the one hand, another aspects of pedagogical demands that will affect the teaching and learning process are heard, and on the other hand, institutional definitions regarding the issues of academic permanence and success are advised ( XAVIER, 2019, p. 297-298).

Xavier (2019, p. 297) also points out that these dimensions must be articulated between them so they feed each other back in order to be effective in their training purpose.

Thus, it excludes “the technical-administrative responsibilities that are attributed to them, because these deviate from their propositional and intervention character, which, consequently, causes difficulties in defining identity and institutional recognition”. From the clarity of the functions that must be triggered by the professional who develops pedagogical advice, the importance of their work in HEIs is reinforced, especially in the perspective of change and transformation pointed out by Lucarelli (2008). In this direction, the author emphasizes, “the Pedagogical Advisory is present as one of the possible resources to which the institution can turn to undertake the transformation processes in the field of education” (LUCARELLI, 2008, p. 4).

Assuming a careful posture with the professional definition, Nepomneschi (2004) warns about the dangers of placing those responsible for pedagogical advice in a position of saviors, of those who can solve all pedagogical problems, a concept that is instituted by virtue of the multiplicity of tasks compelled to function. The author reaffirms that placing the UPA in this perspective opens the possibility of “excluding from the members of the teaching group or team the responsibility for a task elaborated in common, programmed, discussed and shared” (NEPOMNESCHI, 2004, p. 57). Thus, the idea of partnership, of doing and solving together, is a necessary condition, as already mentioned, for effective advisory work. In other words, thinking about Pedagogical Advisory implies thinking about a person or group of people who are the articulators of those pedagogical tasks within their competence, understanding that there are other participants in these processes and that only collaborative work will effectively legitimize the UPA's function.

Reinforcing this reference, Nepomneschi (2004) raises facilitating and hindering conditions that are placed in front of the work of the UPA. Among the facilitating conditions is institutional support, and, for the author, when it’s done by management, professors and students, it legitimizes the function. The legitimacy of the UPA's role places it in a prominent place within the institution, promoting the awareness of teachers about the importance of a department that is responsible for their permanent training. Also according to the author, this legitimacy is better achieved when the sector is composed of multidisciplinary teams, promoting stimulation of proposals for curricular and pedagogical innovation.

On the other hand, the obstacle conditions are characterized, especially, by the scarce resources destined to the Advisory, conjugated with the excessive volume of work. Often, there is also the absence of a suitable physical place for the advisory team, an issue aggravated by disagreements between team members. In the case of Argentina, Nepomneschi (2004) defines that non-professional positions hinder the function, as well as the bad distribution of time. Difficulties regarding gender issues, in which the majority of advisors are women and the non-recognition of the advances achieved, associated with the difficulty in communication in the various segments, make the advisory work difficult, as well as leading to low adherence of teachers in the training developed by the UPA.

The Trajectory of the Research

In methodological terms, this research was done with a qualitative approach, based on a multiple case study design to address issues related to the professional construction of UPA, in its performance regarding the improvement of pedagogical processes that occur in the university context. We highlight the axis that runs through all the advisor's actions, that being, teacher pedagogical training. Specific cases were analyzed that have contextualized and unique experiences and that bring within themselves all the complexity of the UPA's professional trajectory.

The study of multiple cases (YIN, 2001) helped us to understand that each of the cases analyzed had a specific cut of reality. It was possible to look at each of them, assimilating their singularities to articulate them to the ones found in the other researched spaces. It is important to reaffirm that at no time in the research we had the intention to make any comparative study between the loci of investigation, but to analyze each one of them in its essence, looking for points of similarities and uniqueness between them.

The research took place on public universities. In Brazil, we focused on federal universities, and in Argentina and Uruguay on national universities that already develop a consolidated pedagogical advisory work. Regarding Brazil, the institutions were called Universidade Br1 and Universidade Br2; Regarding Argentina, the two faculties surveyed are presented as Faculdade Ar1 and Faculdade Ar2; to Uruguay, are addressed as Faculdade Ur1 and Faculdade Ur2.

We chose these institutions based on prior knowledge of the advisory work carried out by them, knowledge that was achieved through partnerships with the Group of Studies and Research in University Pedagogy (GEPPU1), of which the researchers and authors of this work are effective members. Such knowledge made it possible, in advance, to know that both Brazilian universities and those of the two countries surveyed have a history of scientific production in the area, significantly contributing to the expansion of the advisor's professional field.

The research participants were university pedagogical advisors who were working in these universities at the time of data collection. This moment, in Brazilian institutions, took place in 2018, and in Argentina and Uruguay, it took place in 2019.

Data collection was carried out through different research instruments, which included questionnaires, interviews, focus groups and document analysis. Gerhardt and Silveira (2009, p. 56) understand that data collection is “a set of operations through which the analysis model is confronted with data” and reinforce that it is a fundamental moment to think about both instruments and data throughout the collection process, carefully, always asking the questions: “What to collect? With whom to collect? How to collect?” (ibid.). These questions guided choices and procedures during the collection and, for this reason, we sought not only the quantity, but also the quality of each data collected, using different instruments and trying to take a closer look at each one of them.

In Brazilian institutions, it was possible to hold focus groups and apply questionnaires that allowed a first contact with the most personal ideas of each participant. Gerhardt and Silveira (2009) emphasize that the elaboration of a questionnaire must be careful and needs to take into account the types of questions. Through this process raising three types: open, closed and mixed questions. In the case of this research, we chose to develop open questions, as the intention was that the participants could answer freely and clearly to the questionnaire, presenting their understanding of the UPA's role. Sixteen questions were elaborated that sought to know each participant, their professional trajectory within the function, the scope of their performance and their vision of pedagogical advice.

From the questionnaires, we carried out with the focus group. Barbour (2009) considers the focus group to be a technique very appropriate, both for research in the health area and in the social sciences. He explains that there is a differentiation between techniques that can be confused with focus groups. According to the author, there are group interview techniques in which the intention is to listen to each individual about their impressions and views, without a necessary interaction. It emphasizes that for this group meeting to be configured as a focus group there are specificities in the technique and one of them is that, being a group meeting, what must be stimulated is the interaction between the participants, in addition to the interaction with the researcher. This is one of the strengths of the proposal, and in this research, it was well observed. Thus, interventions were carried out at every moment of the focus group, in order to achieve the objective of having the participants’ dialogue with each other, explaining their points of view.

In the institutions of Argentina and Uruguay, however, the means to collect data were different, starting with contacts. Even with prior knowledge of the people who would supervise the work, distance and differences in academic calendars complicated the data collection process. During this period, in the researched places, we did semi-structured interviews, as the possible contacts were with only one individual from the Pedagogical Advisory group of each researched college, having the lack of time as and justification to the unavailability to reunite the group in a simultaneous discussion. Considering it, the questionnaires were not sent and only the interview was carried out based on the same script of questions. Gerhardt and Silveira (2009) highlight the interview as being “an alternative technique for collecting undocumented data on a given topic. It is a technique of social interaction, a form of asymmetrical dialogue, in which one of the parties seeks to obtain data, and the other presents itself as a source of information” (GERHARDT; SILVEIRA, 2009, p. 72). They also consider that there are different types of interviews, defining them as structured, semi-structured, unstructured, guided, group and informal. They present the semistructured interview as one in which the researcher “organizes a set of questions - a script - on the topic being studied, but allows, and sometimes even encourages, the interviewee to speak freely about issues that arise as a result of the main theme” (GERHARDT; SILVEIRA, 2009, p. 72). The type of interview used in the research was semi-structured, since, despite the existence of a script previously prepared and already applied in Brazil, the interviewees spoke freely about each question posed. As the conversation flowed, some questions ceased to make sense in the process and others emerged that helped in a better understanding of the researched object in that specific locus. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. All were carried out in loco, that is, the researcher traveled to each of the institutions to be with the participating professionals.

In Argentina, it was also possible to observe two experiences, one teacher training course carried out by the Pedagogical Advisory of the faculty and the other observation as a student in a discipline of the Education Sciences course. Teacher training was part of the Carrera Docente course, developed by the institution's Pedagogical Assistance area. The target audience were the professors of the Dentistry course, especially those recently hired and with less experience in teaching. However, more experienced professors also participated, with their functional lives well developed within the institution. The second opportunity was the Didactica del Nivel Superior course, taught by one of the research participants. This discipline is an integral part of the curriculum of the Education Sciences course, a course dedicated to the basic education teachers at the institution.

Gil (2008, p. 100) emphasizes “observation is nothing more than the use of the senses in order to acquire the knowledge necessary for everyday life. It can, however, be used as a scientific procedure. The author states that simple observation favors and facilitates obtaining other hypotheses, in addition to enriching the data. In the case of the aforementioned experience, observation was fundamental for a better understanding of the training process developed by the pedagogical advisors and of how it has affected the teachers, who repeatedly gave witness to this in face-to-face meetings. It also allowed us to understand the importance of having a discipline that deals with Higher Education in undergraduate courses, especially regarding the epistemological field of Didactics.

Regarding the documents, all were obtained from the pages of the universities and/or with the help of advisors who sent files that were not available online. All were analyzed so that they could clarify the view on the other data collected. Lakatos and Marconi (2003) state that documental research is a very important procedure to complement or compose data collection. In the case of this research, collecting documents that deal with the organization of institutions and Pedagogical Advisory Services, such as resolutions, PDI, reports, etc., was extremely important to complement the data obtained through questionnaires, focus groups, interviews and observations.

In order to carry out these analyses, due to the characteristics of the research, we chose to use the Content Analysis method. The dialogue was with Bardin (2011), who considers

Content Analysis as “a treatment of the information contained in the messages” (BARDIN, 2011, p. 41), in other words, it is essential to think of this type of analysis as a treatment of information, a detailed look at the messages obtained through data collection, whether written, recorded, perceived through observations.

Content Analysis can be an analysis of "meanings" (example: thematic analysis), although it can also be an analysis of "signifiers" (lexical analysis, analysis of procedures). On the other hand, descriptive treatment constitutes a first stage of the procedure, but is not exclusive to Content Analysis. Other disciplines that focus on language or information are also descriptive: linguistics, semantics, documentation. With regard to the systematic and objective characteristics, without being specific to Content Analysis, they were and continue to be important enough to insist on them (BARDIN, 2011, p. 41, author's emphasis).

It is, among other things, an action of description, but not just any description, it needs to be an objective, systematic description. The author also emphasizes that Content Analysis appears as a “set of communication analysis techniques that uses systematic and objective procedures to describe the content of messages” (BARDIN, 2011, p. 44). In this way, it is important to realize that the listing of categories, as well as dimensions, is not something achieved by mere deduction, but by an arduous work of studying the data, which allows categorizing them and reflecting on the questions posed, in the midst of a look at all that was collected. Thus, categorization “is an operation of classifying constitutive elements of a set by differentiation and then by regrouping according to gender (analogy), with previously defined criteria” (BARDIN, 2011, p. 147).

In order to analyze all the data collected, each one of them was treated in order to evaluate the information in the documents, the answers to the questionnaires, as well as everything that was said in the interviews and focus groups, in addition to the observations. For this reason, we sought to be faithful to the data collected and to the theoretical foundation, to the research question, as well as to the objectives. After a careful look at all these aspects, we created the categories and dimensions explained in the doctoral research, which underpins the scope of this work.

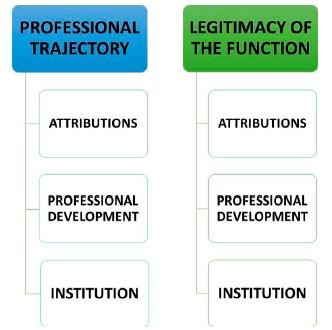

Within the “Professional Trajectory” category, it was possible to observe that there are different paths in each institution, even when they belong to the same body, both in Brazil, in federal universities, and in the faculties of universities in Argentina and Uruguay. It will be possible to notice that there is a wide range of actions in the professional intervention of the UPA and that these experiences end up affecting their professional identity.

Likewise, in the “Legitimacy” category, it was possible to perceive that the issues of valorization, recognition or non-recognition of the function, interfere greatly in greater or lesser possibilities of action of the university pedagogical advisor. Even when dealing with different trajectories and degrees of legitimacy, they all end up meeting at some point along the way, in situations, conditions, recognition and other elements that permeate the profession.

In order to meet the scope presented in this article, the dimension "Attributions" will be addressed, within the category "Professional Trajectory", delimited in the research that underpins it (CARRASCO, 2020).

The Attributions of University Pedagogical Advisors and its Implications on the Development of Their Professionality - An Analysis

When analyzing the data collected through the questionnaires, the experiences reported in the focus groups and interviews, and the documents, we recognize that there is a significant amount of attributions delegated to pedagogical advisors. We verified many variation in activities and the existence of different ways of performing the function, given the institutional policies that permeate this sector. This diversity is well explained when we list the attributions that are attributed to advisors, both in Brazil and in Argentina and Uruguay, highlighting:

Development of Pedagogical Course Projects (PPC);

Assistance to students;

Meeting the individual demands of professors;

Creation and regulation of courses;

Curricular reformulation;

Development of regulations;

Review of evaluation processes;

Procedures linked to distance education;

Monitoring of institutional projects;

Organization of training events;

Participate in commissions;

Proposition, planning and organization of pedagogical training activities.

However, it is evident that not all advisors carry out all these tasks. There are places where the professional works alone in the sector, as it is a decentralized campus, and, in these cases, he is either asked to fulfill all these roles (which becomes unfeasible), or, he ends up dedicating himself to only part of the demands, because it is not possible for only one person to develop them fully. In view of this, the institutional reality ends up determining the logic of professional intervention of the advisors, thus contributing to the construction of a given identity. We understand this to be a very delicate aspect, as the identity construction of advisors often ends up being at the mercy of personal and non-institutional policies, generating confusion in their field of action that impact the contribution they could make, in different demands and scenarios.

Regarding advisors who work with larger groups, in a better-structured sector, these, even in the face of adversities, share responsibilities among themselves. However, it refers to a non-isolated division, since all the UPA always mention the importance of all members of the Pedagogical Advisory being aware of what is happening, in a general and broad way. In this way, each UPA is able to develop other responsibilities, in the event of the absence of any of the professionals, without compromising the performance of the functions assumed by the Advisory. This articulation was felt in almost all the institutions surveyed, although it demonstrates that this is an organization of the advisors themselves, that being, it is not an institutionalized or guaranteed action.

In the context of Brazilian universities and Uruguayan faculties, which formed the locus of this research, the division of the advisors' attributions is well marked in their regulatory documents. In the faculties surveyed in Argentina, there are slightly different referrals. At Ar1 there is a small team of three advisors who are in charge of all the work and share responsibilities. However, they have are supposed to form action teams with other partners of the institution itself for the development of projects within the area assigned to them. The Pedagogical Area of Ar2, however, does not present such a marked division of tasks. In the dialogue with Participant 2, it is clear that Carrera Docente, the course offered at this location, is developed and carried out by all five advisors who work in the Faculty's Education Area. That being so, we highlight the fact that this Advisory Board assumes fewer attributions and is especially dedicated to teach the university professors, which favors the idea of collective work, as they are directed to a specific task. A broad one, but specific.

Regarding the fragmentation of the group into sectors, it is necessary to question the situations in which a single person is responsible for a section of the work. Thinking about the dimensions of the advisor's work in an integrated way, therefore, leads to questioning whether the segmentation in the advisors' actions actually contributes to the better development of their responsibilities, in the perspective of a deep dialogue between the subjects of the pedagogical advisory space. We assume with Xavier (2019) that sectorizing cannot equate to individualizing. Because if we do not consider it, how can the work between advisors, the exchange of ideas, the planning and operationalization of actions be done in a collective way? From the interlocutions that took place in the focus groups in Brazil, we infer that there is integration between some advisors, but others are already involved much more, or only, with their own specific attribution, which does not favor an interlocution between the subjects of the group in the decision-making and carrying out actions. We understand that it is necessary to assume a conception of advice that is constituted by training as a transversal axis, so that “to assume the transversality of training means turning all its actions into moments of exchange, interaction, intervention and opportunities for mutual learning” (XAVIER, 2019, p. 299, emphasis added).

Retrieving a little of the history of these advisors joining Brazilian HEIs - Pedagogues and Technicians in Educational Matters -, we found that their sectors emerged, in large part, from the proposal of advice aimed at the new campuses, fruits of REUNI, which fostered the implementation of many courses that had different proposals. Consequently, considering the first objective of the program, which was “to expand access to and permanence in Higher Education” (MEC, 2010, s/p), it is possible to understand that these professionals would be essential in the HEIs, to develop actions with teachers students, in the sense of improving the pedagogical processes.

However, the arrival of these advisors in the institutions occurred without further guidance, and, in many cases, without a clear institutional policy that defined the advisors' role or mapped their functions, in order to direct the professional interventions expected from these new professionals. That being said, it ended up leading the managers themselves to lose the perspective in the attributions of the advisors, sometimes leaving them in charge of demands that were not even theirs, due to the amount of those over administrative technicians. From the testimony of some advisors, this mismatch of management with the organization of Pedagogical Advisory is evident, and signals that it is a persistent condition. One of the advisors at the Br2 university explains that, whenever a new dean arrives, she is asked why the Pedagogical Department has its own regiment. And this misunderstanding stems from the fact that this is the only body submitted to the Dean of Graduation that has a document of this nature, which generates the need for an extensive explanation regarding the entire history of the sector's constitution for the new management. However, the entire group of advisors is fully aware that, if it were not for this institutional achievement, the risk of the Department cease to exist and the professionals end up in other sectors doing technicaladministrative attributions is enormous. In this sense, the importance raised by the surveyed advisors arises in having legislation specifying their functions, which guarantee the permanence of the pedagogical sector. In the Brazilian universities surveyed, there are some regulations that seek to guarantee the existence of pedagogical sectors, which strengthens the permanence of work and better defines the functions of these advisors. However, as everyone pointed out in both institutions researched, this is a constant struggle so that these regulations become, in fact, the institution's policy and institutional culture not be at the mercy of each new management.

In Argentina, the function is already more consolidated, as the Advisory has been in existence since the 1980s, when the political opening took place in the country. However, as in the experiences researched in Brazil, there was a journey, and today the advisors are dedicated to many other tasks that they were not dedicated to at that time. In the faculties surveyed, they explained that, initially, the UPA was only involved with the issues of curriculum reorientation of the courses and their accreditation. However, over time, the need to incorporate other responsibilities into the role of this advisor began to be felt, as there were also gaps in the service provided to professors and students.

The situation of the universities in Uruguay presented some similarities with Argentina, especially about historical questions. A particularity is that an Educational Sectorial Commission, which monitor and regulates the performance of the Pedagogical Support Units, guides every pedagogical sector of the universities. This title, however, may change in every university, but the intention is the same, to offer pedagogical support to the institution. However, even with the regency of the Sectorial Commission, the sectors still have a lot of autonomy of action. Thus, the Ur2 College has a Teaching Unit, and in Ur1, this pedagogical sector has the status of a department of the institution, with agents who are hired as professors specifically to carry out pedagogical advice. According to Advisor 1 of this college, it was an achievement of the Unit that allowed them to have salary improvements, recognized functional status and better working conditions.

It is evident to us, therefore, that any regulation must allow the advisor to undertake responsibilities that fit him in the pedagogical dimensions that are due to him, in dialogue between functions and between people, fulfilling the role of interfering on a positive way in the teaching and learning processes that take place in the courses. We agree with Xavier (2019), that when defining the list of pedagogical responsibilities that are incumbent on advisors, one achieves

[...] in this logic, the integrality of university pedagogical routines and practices. They exclude, in turn, the technical-administrative responsibilities that are attributed to them, because these deviate from their propositional and intervention character, which, consequently, causes difficulties in defining identity and institutional recognition (XAVIER, 2019, p. 297).

For the author, there are two routes that cross all dimensions of the UPA's work, namely “incentive to innovation and pedagogical training” (XAVIER, 2019, p. 298), highlighting that the innovation in both is acting in relation to curricular advice, in the reformulation of pedagogical projects, as in pedagogical advice “through encouragement and collaboration in practices, as well as through training that puts in debate and reflection the pillars of curricular innovation to be met for pedagogical innovation” (XAVIER, 2019, p. 298). Furthermore, Cunha (2014), Lucarelli (2008), Broilo (2015) also address the need to qualify the pedagogical work through the systematization of everything that has been conducted. In this direction, the research of the advisor's practice is the way to be followed, according to the authors.

Cunha (2014), rescuing the importance of the professional development of university professors through pedagogical training and research into their own practice, highlights the need to develop specific knowledge of the teaching profession and training based on the concept of teaching with research. Based on these notes, the importance of pedagogical advisory teams working in HEIs becomes bigger, especially in the dimension of teacher training, reinforcing the need for the pedagogical advisor to “leave amateur spontaneity and assume a professional condition” (CUNHA, 2014, p. 43).

It is, therefore, essential to remember that this training is necessary due to the professional construction of the university professor, which takes place in stricto sensu postgraduate courses, being a training focused on research. It is widely recognized that, to enter Brazilian universities as a professor, even though there is always a request for a didactic class, does not require the applicant to have specific knowledge of teaching. On the contrary, there is little or no incentive for these professionals to dedicate themselves to teach at the graduation courses of the institutions. Cunha (2014) points out that these professors are arriving younger and younger “with little professional experience and scarce pedagogical preparation” (CUNHA, 2014, p. 30). This scenario enhances the role to be assumed by the UPA, since it will be up to them to build training spaces that can discuss knowledge with the teachers, in a condition of in-service training.

In this specific action related to the pedagogical training of university professors, Cunha (2014) presents the training models in different degrees of centralization by those who articulate the training proposals. The models are: (A) Model of Centralization and Control of Actions; (B) Partial Model of Decentralization and Control of Actions; and (C) Decentralized Model for Monitoring and Controlling Actions. In an inference from the analysis of the collected data, we indicate that there is still a great distance for institutions to reach the Decentralized Model of Monitoring and Control of Actions (C). Even in Argentina, where dense courses of teacher pedagogical training exist, and even though they have been raised to the status of a Specialization course, they refer to courses already formatted, ready, prepared without the participation of the teachers who should be, in Cunha's perspective. (2014), subjects in this process. With this logic, it is possible to assume that such formations refer to a more emancipatory approach. Model C will only happen, therefore, if the advisors manage to build an institutional culture of professional self-development with the teachers, so that everyone goes through a process that also favors the construction of a culture of investigation of their own practices.

These models allow, then, to identify the type of training that is being proposed and triggered for university professors, by pedagogical advisors, with reference to what is expected to be achieved. If training is one of the paths that permeates all other dimensions of the advisor's performance (XAVIER, 2019), it is not possible to think that the pedagogical training of teachers can be incipient. It is not by chance that all the advisors that collaborated in the survey, in Brazil and abroad, put pedagogical training as the great challenge within their functions, and it is possible to perceive, in all places, a decrease in training proposals by the advisors’ teams. This is due to factors such as low adherence to training by teachers, lack of support, whether financial or human resources, by the management, in addition to the demands that emerge in the advisor's daily work. These same issues are also major obstacles for the training proposals to evolve towards a Decentralized Model of Monitoring and Control of Actions (CUNHA, 2014). For that to happen, an effective participation of all the subjects of the process would be necessary, that is, advisors, professors, managers and other agents, developing training proposals in the collective supported by attentive listening to the demands and supported by the conditions for their consolidation.

In Brazilian universities there are training offers, however, there is no evidence that they are proposals that affect a continuous and reflective process on teacher’s actions. What can be seen are specific proposals, such as scientific meetings, lectures, workshops, in other words, in the researched universities, an ongoing training process was not found in terms of continuity and perspective of motivate the action- reflection-action cycle. This idea, supported by Donald Schön (1993) regarding the reflective professional, considers that relying only on practice to guarantee the formation of a professional is as incipient as formations that do not propose reflection on this practice, from a collective perspective and theoretical references aligned with was supposed to be developed. Therefore, we agree that

“reflection is not about constantly returning to the same subjects using the same arguments, in fact, it is documenting one's own performance, evaluating it (or self-evaluating it), and implementing the adjustments that are convenient” (ZABALZA, 2004, p. 126). On this logic, Broilo (2015) points out the importance of pedagogical spaces in universities, occupied by advisors, being “a welcoming space to guarantee discussion, reflection and dialogue between professors” (BROILO, 2015, p. 240). It emphasizes that it should be a space for reflection about innovation that leverages the construction of knowledge and the break of the reproduction of merely transmissive ways of teaching. Therefore, it is also necessary that the advisors themselves build their professionalism in the self-management of their training and in the challenges inherent to it.

In Argentina, each of the faculties surveyed followed paths that have similarities and distinctiveness with the training offers that were seen in universities in Brazil. College Ar2, for example, offers teaching training lasting two years, but this training has not yet postgraduate status. Despite being a specific training, which has a specific duration, it ends up not offering any continuity, although the process developed throughout the course is quite reflective. Despite being a very theoretically dense course, the participating teachers are always challenged to relate the content of the meetings with the practice of their classes, including tasks to develop and discuss later. With the opportunity to have observed part of this training, it was possible to perceive the proposed deepening, as well as the articulation of theory with practice. The similarity with the courses at universities in Brazil lies in the noncontinuity, however, being a two-year course denotes greater continuity than the training normally offered in the Brazilian institutions surveyed.

Ar1's training follows similar paths to Ar2; however, the course trains the teacher at the Education Specialization level. A feature to be highlighted in the courses offered by these two faculties is that they are pedagogical training totally focused on the areas of activity of the professors, that is, the course developed at Ar2, as well as the one developed by Ar1, articulates pedagogical knowledge with the disciplines developed by teachers in their specific areas. This characteristic differs from the training that deal, solely and exclusively, with pedagogical issues decontextualized from the reality of the teacher. The contextualization element, then, seems to us to be elementary in pedagogical training, both in terms of valuing and focusing on the specificity of a given area and in the correlations of the areas in a context in which the teacher and his students are historically situated.

In Uruguay, the pedagogical advisor of the Ur2 College explains that they were left with two models for offering training: one for newcomers, seeking to address important issues of performance in the classroom, articulating their practices with the course's Teaching Plan; and another, as a training proposal on demand, through public notices that are launched every six months by the Pedagogical Sector. On this second one, teams of professors who work in the same course request the intervention of advisors, in situations of real problems faced in the classroom. This on-demand training proposal was the solution found for the low adherence in other trainings offered by the sector.

At the Ur1 college, there is great concern with institutional evaluation issues and the Department devotes a lot of time to this. The pedagogical training of teachers is offered in shorter but constant proposals. The advisors also watch over the Master’s in Education that exists within the institution for professors who wish to specialize in the area, an attribution due because it is a college in Health, therefore, the UPA are the specialists in the field of Education.

The findings reveal that there is great adherence to the pedagogical training offered in foreign faculties, unlike the reality of Brazilian universities. Hypothesis can be raised to try to understand this fact; one of them is related to the requirement of training to be a university professor, which is different in these countries surveyed. In Brazil, a doctoral degree is required to fill the vacancies for professors. In Argentina and Uruguay, it is possible to be a professor at the university as soon as one graduates, because, in these countries, the professor will not necessarily be the researcher. Therefore, trained in the profession, he can function as a teacher. In this logic, seeking specific training in teaching would be something that would really be effective in the career of these professionals, which, for Brazilian university professors, masters, doctors, and post-docs, may seem like a dedication with little reason, since they have a long journey of training in the specific area and in research. In addition to this issue, there are other points that permeate the teaching culture at the university, such as the lack of appreciation of pedagogical aspects in Higher Education, nor the recognition of the complexity of teaching.

Another hypothesis would be related to the training models offered. We believe that, perhaps, a denser proposal would arouse greater interest in the participation of teachers, to the detriment of specific training proposals, which do not offer an opportunity for continuity and follow-up. However, this would depend on a change in the perspective of university professors to recognize that, in fact, they need to improve regarding the lectures and its consequences.

A third hypothesis would be a proposal that would result in certification and that would bring functional advantages. In Brazil, there were different perspectives on this. At Br1, there is a movement for pedagogical training to have weight in the evaluation of professors, which happens in the faculties surveyed in Argentina and Uruguay. However, as Xavier (2019) has already reported, and was evaluated at Br2, there is an opposite movement, in which the probationary internship is associated with the teacher-training program. In this way, instead of certifying in a favorable way for teaching adhesion, training is quantified, giving it the character of an instrument of approval in a probationary stage. Faced with this reality, there is a desire from advisors to change this perspective, as they do not want to link the training processes to functional issues restricted to the probationary stage.

All these hypotheses, which can be seen as assumptions related to the training of university professors, lead to resize the opportunities for professional development of university professors. In the same direction as Cunha's (2014) training models, Marcelo (2009) shows that it will not be through transmissive and centralized training models that one will arrive at the transformation of the conceptions and, consequently, of the teachers' practices, but through models of collective construction of knowledge. These are processes that must occur in the long term, that is, they must be continuous, to carefully be able to relate theory and practice. Some processes that must occur in the long term, that is, they must be continuous, taking care to be able to relate theory and practice. According to the author, training should have a collaborative and collective nature, never individual, and should be developed from the context experienced by the group of professionals, having meaning within what teachers develop in their day-to-day in the classroom.

Thereby, thinking about the daily work on the classroom and assuming that pedagogical training permeates all other dimensions of the UPA's work, it is also important to analyze how it works with students. Thus, understanding that the advisory work cannot be dichotomized, we defend that the interconnected actions will be able to promote real changes in the teaching and learning processes of the university. Thar is a delicate subjetc, because in the institutions studied, the division of tasks by the teams of advisors, sometimes with a focus on students, sometimes with a focus on teachers, ends up fragmenting and diluting even more the attributions and methods of development of the advisory work, dichotomizing the guidelines among the subjects themselves (teachers-students-coordinators). As if, there is no collective, coherent and correlated work in the face of the demands of the institution itself.

In Brazil, the two universities surveyed concentrate service to students in the sectors responsible for pedagogical advice. There are proposals for tutorials for incoming students, proposals for individualized care, for formative moments that seek to develop organizational practices, time management and valuable information about the institution. Thus, in the Brazilian case, there is a significant attempt not to fragment the work of the advisors involved with teachers and students, because, despite having dissimilar needs, they are in the same institutional space, whose formative processes experienced by both need coherence, connection, and interrelationship.

In Argentina, the Ar1 college does a well-established job in serving students, presenting two projects for this purpose. The tutoring of students takes place at various stages of their graduation period, at admission, in internships and in the final year, to provide guidance on the job market and possible actions, welcoming the anguish and difficulties of students at these specific moments. The Faculty’s Pedagogical Sector organizes this tutoring; however, it has the participation of veteran professors and students, which makes the project very fruitful for its action. Tutoring groups are formed and they guide students throughout their academic career. There is also the Academic Literacy Program for new students, who learn the language of the academy, specifically in Veterinary Science. It is organized in the same way, that is, in partnership with veteran teachers and students, with the supervision and monitoring of the Pedagogical Sector.

At Ar2 College, the Education Area, despite focusing greater efforts on teacher training and direct advice to teachers, is also commit to the pedagogical assistance of students who have learning difficulties during the process experienced at the institution.

In Uruguay, in the two colleges surveyed, other bodies provide student assistance; however, they declared that, not infrequently, they form partnerships with these spaces to assist in these services. In this reality, therefore, it does not refer to a specific function of faculty advisors.

Although we understand that student service is an essential action in the training process triggered by the UPA, it is necessary to indicate limits for this service. As in Argentina and Uruguay, the Pedagogical Sector helps students of a strictly pedagogical nature, which was not the case in Brazilian universities. What was observed in the Brazilian case, from the data collection, is that the UPA addresses all types of problems that the student presents. In addition to pedagogical issues, the advisors deal with social, psychological and any other problems that may arise, albeit in an initial screening condition for later referrals. When problems that are outside the pedagogical scope are perceived, students are referred to the psychological and social care sectors, however, they undergo pedagogical advice in the first instance, most of the time, as the advisors report. If the service provided by this sector had a strictly pedagogical focus, the articulation with the elements that involve the teacher could generate more decisive training processes. This means that, if the advisor is dedicated to the training of teachers in the academic space and participates in the reformulation of curricular and evaluation proposals, knowing what happens to students in class, based on attentive listening to their demands, can be essential for directing training actions in all these dimensions.

Research is another attribution analyzed in this dimension. From the data collected in the gathering and based on the attributions listed by Xavier (2019), it is possible to infer that in Brazil, University Pedagogical Advisors do not work with research in a professional way. It may happen that they conduct their own research in their masters and doctorates, however, there is no research action in the department where they develop the pedagogical advice. Thus, in addition to the list of responsibilities recurrently verified in Brazilian institutions and mapped by Xavier (2019), both at Ar2 and Ar1 there is a very specific action of the faculties surveyed in Argentina, which is research in the area of pedagogical or thematic advice that are related to teaching. Thus, in addition to the list of responsibilities recurrently seen in Brazilian institutions and mapped by Xavier (2019), both at Ar2 and Ar1 there is an extremely specific action of the faculties surveyed in Argentina, which is research in pedagogical or thematic advice that are related to teaching. At the Ar2 College, a researcher was hired by the sector to boost research in the area and there is a structure set up in this perspective. At the Ar1 College, according to the interviewed advisor, research ends up linked to time issues, but they happen. They even organize a scientific journal of the faculty where they can disseminate their investigative findings.

The question of research as an UPA attribution led us to think about the objective of this action within the institution, on the part of these professionals. It was observed that abroad, doing research in the area is already a consolidated action in three of the four institutions surveyed. In Brazil, this action is not yet a priority within the advisory spaces, but it is an issue to be reflected upon, especially when the relationship between self-training and professional development at the UPA is proposed with research into the practice itself.

To think about the importance of this action, Cunha (2013) rescues the paradigm of modern science. Inspired by the exact and natural sciences, initially it was the foundation of these fields that accompanied the social sciences in the scope of research, due to the search for legitimacy regarding the investigation of the epistemological field. Both social and educational issues were at the mercy of a neutrality that could not be achieved in the study of field phenomena. Cunha (2013) points out that a paradigm shift was necessary for the social sciences to assume another posture through research. Thus, works in the various dimensions of this field were breaking through these barriers, which affected the research assumptions in the area.

When the assumption is made that research can be a key element for emancipatory training, the idea of coherence between investigative processes and an evaluative proposition of education is being adopted. As the paradigm of technical rationality gave way to the understanding of the educational phenomenon as socially and culturally produced, there were significant changes in the ways of producing knowledge about education (CUNHA, 2013, p. 620).

Therefore, thinking about the research that can be carried out by pedagogical advisors leads to reflecting on what assumptions such research will be meeting. If research in Education needs to be seen as a social and cultural phenomenon, to what extent will this research contribute to improve the educational field, or University Pedagogy? If research actually assumes its questioning condition and its contribution to emancipatory educational processes, as emphasized by Cunha (2013), it is necessary to think about investing time and energy to be developed by the UPA. Indeed, it would be possible not to assume it as a new attribution, but rather as another transversal dimension to the advisor's role, as well as training and innovation, from the perspective of Xavier (2019). Thus, we assumed, in this study, that research should be part of all advisor functions, not an afterthought; it should therefore be the theorizing of its practice, a requirement of its own function.

The analysis makes us reach the trajectory covered by the UPA, verifying that, although initially the pedagogical advisors in the universities researched in Brazil were seen as a technical-administrative agent, who would develop their professional performance according to the demands of the management, they managed to , through their own efforts within a collective dimension and through the recognition and help of some other agents in the spaces of action, to clear barriers and build a new path. One proved to be of significance within the function, seeking and giving meaning to it over time.

In Argentina and Uruguay, this journey also took place in terms of important advances, since, initially; the advisors were dedicated only to curricular orientation and to the accreditation of courses with the federal agencies of those countries. Over time, they assumed fundamental and significant formative roles that, according to the testimony of one of the interviewees, it is not possible to see these institutions without the Pedagogical Advisory Services, which “today are an integral part of all the work developed at the university” (Interview with professor Ar, 2019).

Outcome and Cosiderations

From the general objective of the study, to understand the professional trajectory and performance of the University Pedagogical Advisor, a path was traced to search for pedagogical assistance experiences that would support the proposed research. It was necessary to look at spaces where there was an already consolidated trajectory of advice, which demonstrated how the path had been structured. With the commitment to verify how the professional action of the UPA has been taking place, it was possible to experience each of the spaces surveyed, seeking to know the different paths taken by the advisors in this professional construction within their institutions.

We verified that the historical context of each place, and even of each country, greatly interfered in the development path of this professional action. Brazil, for starting the process of expanding access, consequently opening spaces for pedagogical advice within the university belatedly, is still far from achieving the legitimacy of the UPA's function. In Argentina and Uruguay, this path is already more consolidated, without, however, being closed, since it became evident, through the advisors' manifestations, that the fight for legitimacy is constant due to the also constant changes in the social scenario, cultural and political institutions.

It was possible to perceive that the professional action of the pedagogical advisor becomes fundamental when he gains space within the institution and recognition of in conducting his work. It is essential to focus on your responsibilities, realizing the importance of not deviating from them - nor letting yourself be deviated - so that you can conduct your work in such a way that you can achieve the triggering of a whole training process that needs to take place in each of your actions. The institutions surveyed in Brazil and abroad have managed to preserve this essence, despite the numerous challenges they face. The struggle to maintain the spaces they have, and to make them become areas of action, was found to be very strong and very arduous. Space, place, and territory are references to understand training spaces as places that need to be occupied. Space is just the distance between two points, while the place is the occupied space and the territory is the place where sovereignty is exercised (CUNHA, 2010). “Space becomes a place when the subjects that transit in it attribute meanings to it. The place becomes territory when the values and power devices of those who assign the meanings are made explicit” (CUNHA, 2010, p. 56). We observe that this is a struggle that cannot cease. The institutions of Argentina and Uruguay are equally focused on maintaining the essence, but with more structured spaces, perhaps already places, which may be closer to becoming territories.

The specific training of the pedagogical advisor, offered by the institution, is another important topic. If there is a personal search for advisor training, if self-training has been a possibility for advisors to grow, both in Brazil as in Argentina and Uruguay, we argue that there is a need for specific training spaces for this agent, also within the institution. In this sense, the possibility of professional development and self-training is expanded, with a view to improving the processes experienced in their attributions, based on experiences that promote reflection on the role and the resizing of actions, whenever necessary. This does not mean that your personal search should not continue because, yes, it should. However, it needs to be accompanied by other institutional formative experiences, fully engaged with their work, providing meaning to daily activities.

In addition to the training spaces that must be created in the institutions, we affirm that there are other collectives of important reverberation in the training of the university pedagogical advisor, networks to which the due visibility and appreciation must be given. An example of these UPA self-training spaces is the RedUPA2, formed by advisors from several Latin American countries, especially Argentina and Uruguay, with researchers from Brazil. In Brazil, there is a recent initiative called the Study Group of University Pedagogical Advisors (GEAPU)3, which has pedagogical advisors from public and private institutions throughout Brazil and also aims to establish itself as a space for self-training of pedagogical advisors.

Another important space for meetings and learning that we consider fundamental for the self-training of advisors and qualification of their practices, in view of their approach to research, are the Research Groups installed in institutions, specifically intended for this purpose. The Study and Research Group in University Pedagogy (GEPPU), from UNESP Rio Claro, is one of these spaces for studies and research on issues involving University Pedagogy. As there are pedagogical advisors in the group and there are researchers who are dedicated to investigating the field, it becomes a key place for the development of ideas and the opening of new spaces for discussion and learning. As an example, the group's activities include an event that is already going to its third edition, the Brazilian Congress of University Pedagogy (CBPU). In its two editions already conducted, it provided many reflections on various aspects of the UP, including pedagogical advice. In the last edition, held in January 2020, workshops were held on specific UP themes, and, among these workshops, there was the University Pedagogical Advisory. A space where it was possible to discuss the role of the UPA, through dynamics and dialogues, which led the advisors present to advance in their reflections about their professional performance within the universities where they work, contributing to the construction of their professionalism.

We defend, therefore, that all these spaces are of fundamental importance, however, they do not exempt institutions from investing in the organization of their own training places for the university pedagogical advisor.

We noticed the significant effort of the pedagogical advisors in delimiting their role within the institution, which, sometimes, occurs in the few existing regulations. In practice, we verified that, even though the actions are explained in documents and plans, the advisor is still at the mercy of the immediacy of the institutional dynamics, a condition that disfavors his identity constitution. This statement is based, firstly, on what emerged from the focus groups, on the part of the advisors, regarding the little workplace autonomy they have, that is, no matter how much they strive to be protagonists in the processes they develop, they still depend a lot on the institution's decisions about what they will do. However, it is important to raise the question that autonomy is a construction that demands knowledge and legitimacy at work. Would the advisors be prepared to have greater autonomy in their responsibilities regarding pedagogical issues? Thus, as much as there are resistance actions, they are still isolated and not very fruitful in the direction of achieving greater autonomy.

In addition to the issue of autonomy, the dynamics of the institution and immediate problems to be solved, sometimes, limit the specific performance of the professional in the sectors that he should actually work, that is, reconfiguration of curricula and evaluation processes, teacher training, attendance to students, pedagogical advice. Although they see themselves developing typical activities of each of these routes of work, not infrequently, they find themselves stuck to more bureaucratic issues, imputed by the management, which end up stifling the other referrals that need to be done. These conditions make us think about the importance of greater autonomy for the pedagogical sectors of Brazilian universities, in addition to a better structuring, both in terms of personnel and limitation of demands, and the demands that must be considered need to be those that bring in themselves the routes of pedagogical training, innovation and research.

The research issue is another element that needs recognition and visibility in the advisory work. In its place as an articulator of training processes, it would be of fundamental importance that the UPA dedicate itself, as an assignment of work, to research in the field, both to trigger its self-training and to be a builder of knowledge in the field of University Pedagogy and of the University Pedagogical Advisory.