1 Introduction

Because of the celebration of seven decades of the United Nations, it's important to highlight that education as a process has been accepted and defended as a right for all human beings, as it prepares individuals to face the realities of their respective nations or communities and makes them capable of finding the most appropriate economic and social development model.

Thus, digital technology is at the disposal of educational processes and can collaborate to expand this right to all human groups and help a greater number of people in a country to have access to education. In this sense, it's necessary to show advances in the digital world, to develop effective and versatile platforms, to take teaching to all possible spaces and at a low cost, this has been the work of all who believe in digital education. Naturally, it's important to think about the inclusion of the prison population, creating training programs that contribute to the return of these people to society, a thought that is in line with the ideas of social justice (BOLÍVAR, 2012; MURILLO TORRECILLA; HERNÁNDEZ CASTILLA, 2011).

Taking into account the study by Campos (2015), which confirms the need to prove that the rates of relapse for those who have been incarcerated decrease proportionally with the efforts dedicated to the educational-training processes of those who went through the prison system, the experiment described here adopted as the pedagogical model that developed by Moreira (2017) and as an evaluation method the virtual adaptations made by Doménech, López and Velasco (2011), by Dias-Trindade and Moreira (2019) and by Moreira and Dias-Trindade (2020).

Considering that those who lose momentarily or permanently their freedom is can't experience an invaluable asset, even if each person may not have this vision, it was decided to include the ecological-environmental theme because in some way we are also “stuck” with invisible forces because the natural world affects the human world. Just as the prison attacks this intangible value called “freedom” and it forces people to obey specific rules in prison, Nature leads the human being to obey its rules in all the activities of human life, besides its even more restrictive when it is attacked, violated and it appears to be unaware of such rules until it is understood that the “freedom” of the human being depends on the freedom that Nature has to follow its evolutionary course. This parallel guided the experiment and the inclusion of the dynamics here under analysis.

This study is part of the project “Education and eLearning in Prisons in Portugal”, developed by Universidade Aberta de Portugal. The objective was to introduce some group dynamics during a university extension course held in a Porto prison facility, in early 2020, using hybrid sessions to put the strategies designed into practice.

Two different group dynamics, all with a socio-environmental theme, were developed in the program, to extract elements that can be classified as cognitive and social to the chosen methodology, in addition to the behavioral element. This last element, the behavioral one, appeared transparently in the participants' analyzes.

2 Reasons to focus on prison systems

The study understands that crime can be partially inhibited with the help of re-socialization programs (including educational ones), even if it undergoes some questioning by decision-making sectors in any country, it's fundamental to mitigate what Dores (2018) points out as different in the relationship between the dynamics of incarceration and crime. Also, Díaz-Torres (2017) highlights that social exclusion requires an educational response.

Statistics about the prison population are worrying, as they warn society and its corresponding judicial, security and penitentiary systems. With each passing year, it's increasingly urgent to assume and dedicate effective efforts to facilitate the reintegration of this population, so that there is no recurrence. At least that is what the Council of Europe (2013) pointed out in Recommendation 89 (12) of its Committee of Ministers when referring to education in European prisons as a policy to make these citizens more human and facilitate their return to society.

In the Portuguese reality, as Moreira, Monteiro, Machado and Barros (2016) point out, “there is also an awareness that education in the context of seclusion must be a reality”, highlighting the cooperation between the Ministries of Justice and Education through Joint Order 451/MJ/ME, of June 1, 1999. It was on that same day that teaching in prisons was regulated in all the Portuguese territory, at the level of all teaching. The arrival of the digital signal in some Portuguese prisons, within the scope of the protocol signed in April 2016 between the Open University (UAb) and the Direção Geral de Reinserção e Serviços Prisionais (DGRSP), allowed for new dynamics of training, learning and the development of training activities with results in the acquisition of learning skills (DIAS-TRINDADE; MOREIRA, 2019; MOREIRA; DIAS-TRINDADE, 2020).

We hope that this work will join the existing programs, always following the premises that the development of digital competencies is one of the aspects of social inclusion, as defended by Moreira, Machado and Dias-Trindade (2018) and Warschawer (2004).

3 Methodology

As mentioned above, the dynamics introduced in the extension course in a prison, in the region of Porto (Portugal), formed part of a research based on DBR - Design-Based Research, based on the model being executed in the Portuguese prisons of use of cinema as a strategy for the development of learning contexts (DIAS-TRINDADE; MOREIRA, 2019; MOREIRA; DIAS-TRINDADE, 2020). It's an effort that promotes “strict and reflective research”, useful in learning environments where theory and practice are reconciled (WANG; HANNAFIN, 2005).

Within a hybrid learning ecosystem, that combined face-to-face sessions with virtual ones, 17 students/inmates of Portuguese, Brazilian, and Mozambican origin participated (with the number of participants varying in each dynamic). These same dynamics took place in the classroom and the virtual learning environment Moodle On@Pris, from Universidade Aberta, at the Educonline@Pris Virtual Campus (in operation since the end of 2018), to complement the planned activities.

To analyze the data resulting from face-to-face dynamics, Bardin's content analysis (1977) was used, with a fluctuating reading of all responses to the research, to align common themes and particularities, depending on the individuality of each case.

The research project of which this work is part hasn't been submitted to an ethics committee but has followed the ethical guidelines published by the Portuguese Society of Educational Sciences (SPCE, 2014). Thus, throughout the investigative process, the authors maintained high levels of vigilance and self-reflexivity concerning ethical issues, as defended by Mainardes and Carvalho (2019).

The program was designed based on cinema as a didactic-pedagogical instrument and organized in six face-to-face sessions (with fourteen-day intervals between each session, during which debates continued in the virtual environment). The dynamics under analysis were included in the program, in two different sessions, always before viewing the films in the prison's library. The students/prisoners received information and specific material in each session, using the physical space and the virtual space afterward, to discuss the issues prompted by the films and the dynamics themselves.

The dynamics prepared by the researchers were used in this experiment in the face-to-face steps, with the intention that their results were integrated into the debates held in the virtual environment. Accordingly, the first dynamic carried out tried to identify the elements of the nation considered most important for possible reconstruction, after a hypothetical elimination. For this same identification, the main question to be answered was: what would be the ten most important things that could be protected from the total destruction of the country, in the supposed case of being able to save them without any restriction of any kind?

The second dynamic consisted of performing a “Semantic Test”, according to the model of analysis based on Valdez Medina (1998) and following the recommendations of Doménech, López and Velasco (2011). This test, without requiring further debate, launches results that allow, starting from the central concept of citizenship, to explain the organization of information in humans, as advocated by Sarmiento Silva and colleagues (1992). Thus, students/prisoners were asked to leave in writing the first familiar concepts that would appear in their minds when they were stimulated by a word called the word “Node”, as proposed by the adopted methodology. The motivating word was: “Citizenship”. The words requested are called: “Defining Words”.

For this dynamic, and following the methodological process adopted, the values obtained to allow the analysis of the responses of students/prisoners. In this case, there are four values: SAM (greater semantic weight); J (total number of words); PS (semantic weight), and DSC (semantic distance between words) which respectively translate as follows.

The SAM value, more than a value, is the group of words that obtained the highest semantic weights (PS). This value or group of words represents the core of what may be the psychological meaning of the central word chosen in the dynamic.

The “J” value is the total of different defining words identified and includes all those that can be called synonyms or equivalents. In this first analysis, the rigor of the interpretation of what could be equivalent wasn't strict. In any case, this value becomes a tool to assess the richness of the semantic network.

Another highlighted value is the “PS”, or semantic weight, the product of the sum of all multiplications, of the number of occasions that the defining word appears, times the value of the hierarchy given to that word; that is, if a word appears twice with hierarchy one and elsewhere with hierarchy four, the PS of that word will be the sum of (2 * 5) + (1 * 2); therefore, PS = 12. Thus, the higher the hierarchy, the greater the multiplier; the higher the frequency of the appearance of a word, the greater the product, or PS.

Once the PS is obtained, it's necessary to calculate the semantic distance between the words. This is the DSC value, a quantitative value expressed as a percentage that separates the defining words from the whole set. That word with the highest semantic weight represents 100%, from which the relative distances of the other defining words will start.

As the central theme revolved around environmental citizenship, concepts like ecology; sustainability; natural resource; bio-cyber laws; exponential growth, among others, were all highlighted in the debates as human elements compatible with natural mechanisms. All of this didn't prevent reflection and debate about their own pre-reclusion experiences, as professionals and people. Participants discussed with propriety about the current state of development of their nations.

Each of these dynamics was articulated with the movies that were watched, preceding the viewing, providing an initial motivation that would later be integrated into the debate held after the viewings and was prepared to take into account the importance of the teaching mediation processes (THERRIEN; AZEVEDO; LACERDA, 2017) in the creative development of pedagogical activities based on the use of social experience (KONDRASHOVA et al., 2020).

4 The project “Environmental education and citizenship in a prison environment”: results and discussion

First dynamic

After the official presentation of the course and the description of its characteristics and conditions to be fulfilled, and before the presentation of the documentary “An Inconvenient Truth”, the first dynamic was launched. The results are presented by classes in table 1. It deals with the hypothesis of a nuclear holocaust. Participants were asked to form a council with unlimited power to save the ten most important things they considered necessary to rebuild the country and make it a new nation in the event of destruction.

Table 1 Frequency of the ten most important elements for reconstruction

| Class | Subsistence | Architectural Heritage | Ecological heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Element | People / Population (2) Food (2) Water (2) Schools Roads Airports Cultivation Fields Hospitals Animals Plants Health care Assorted materials National Library |

Jerónimos (2) Santuário de Fátima (2) Palácio de Belém Torre do Tombo Museums Churches Torre dos Clérigos Palácio da Pena Castelo de Guimarães Castelo de São Jorge Baixa Pombalina |

Tejo River Estuary (2) Serra da Estrela (2) Pinhal de Leiria Buçaco Ecoss. Miranda do Douro Serra de Sintra Complexo Arrábida Compl. Peneda-Girês |

| Total (50) | 16 | 13 | 10 |

| % | 32 | 26 | 20 |

| Class | Intangible heritage | Intangible values | Others |

| Element | Douro Wine Zone (2) Fado Alentejano Singing Pauliteiros de Miranda Mirandesa language |

Knowledge Wisdom Humillity |

National Assembly (02) |

| Total | 06 | 03 | 02 |

| % | 12 | 06 | 04 |

Source: Author's own.

The collected data correspond to a sample of 33% of the participants because only six people participated in this session. Thus, table 1 shows the frequency of the chosen elements, obeying the chosen classification, and not all of them wrote the 10 words requested, table 1 has a total of 50 words.

Examining the data obtained, some observations may induce a kind of thinking that is quite common in this type of dynamics, the participants tend to focus their reconstruction thinking on those elements that guarantee their physical survival, such as the elements on food, and to them offer physical and mental health, in addition to having a minimum number of human beings to carry out this task. However, as indicated by Page (2018), even with the opportunity to start over, there is always a greater concern to save what the country already has, in the case of Portugal: the basic service infrastructure and means of subsistence. One-third of the group, 32%, chose these elements first.

Another aspect that draws attention is the importance that students/prisoners gave to architectural aspects of historical-anthropological character, as 26% of them valued buildings and monuments that seem to constitute essential elements in the lifestyle of the Portuguese citizen (PAGE, 2018). Add to that the 12% who chose an intangible heritage, which somehow also form part of the imagery and history of the participants, mostly born in Portugal.

In the same way, the awareness about the ecological importance of national environments is surprising, which for 20% of the elements is identified as an element worth saving for a nation under construction. This shows that there is a certain concern for the ecology of Portugal, essential for survival and that it needs to be protected.

Finally, regarding this first dynamic, it can be said that, while 68% of the elements chosen in a certain way represent what the country even has in abundance, those elements that seem to be the most criticized for their absence worldwide, as is the case of intangible human values - essential to drive progress and political and economic programs in any country - were the least cited.

Thus, only three elements out of 50 (6% of the total) correspond to those that always seems absent when talking about the model of human progress adopted in many countries of the world. Concerning “Wisdom” and “Humility”, these were the only intangible values mentioned that together with “Knowledge / Training”, despite being more of a human right than a value, were considered important elements to administer, govern or manage a new country. In this specific case, the imagination of students/prisoners isn't much different from free citizens. It's the absence of awareness about the importance of these intangible elements that the course would focus its attention on later sessions.

Second dynamic

Reinforcing what is mentioned in the methodology, the dynamic in question tries to establish what is known as the “semantic network”, a technique that comes from psychology and aims, according to Doménech, López e Velasco (2011), to give meaning to a certain issue, subject or object, after understanding the organized individual or collective concepts that give it meaning.

It's important to highlight that the dynamic allows individuals to be stimulated to bring from their semantic memories words or concepts that, according to Garofalo, Galagovsky e Alonso (2015), are long-term information stored arbitrarily in their memories.

Table 2 Defining words of the central concept (node) “Citizenship”

| F/R | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Volunteering | Peace | Legislation | Integration | Equality |

| 2 | Education | Politics | Sociality (?) | Learn | Share ideas |

| 3 | Care for others | Solidarity | Good behavior | Cleaning | Love people |

| 4 | Commitment | Rules | Society | Rules | Order |

| 5 | Libety | Respect | Order | Education | Fraternity |

| 6 | Education | Environment | Participate | Future | Human |

| 7 | Society | Well Being | Behaviors | Coherence | Justice |

| 8 | Rights | Duties | Help | Cooperation | Rules |

| 9 | Respect | Rights | Duties | Obligations | Reules |

| 10 | People | World | Nature | Rights | Duties |

| 11 | Humanity | Interpersonal network | Opportunities | Inclusion | Accept differences |

| 12 | Respect | Accept differences | Contribute | To preserve | Innovate |

| 13 | Justice | Iquality | Fraternity | Work | Health |

| 14 | Humility | Social differences | Rights | Education | Education |

| 15 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 16 | Caracter | Personality | Objectives | Experience | Local |

| 17 | Good citizen | Look at each other | Responsible | Preserve | Respect the elderly |

Source: Author's own.

Immediately after being asked to enumerate the five words, participants were asked to organize them according to what they understood to be their degree of importance, allowing them to establish a hierarchical order of personal relevance (table 3).

Table 3 Defining words of “Citizenship”, hierarchized

| F/R | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | H5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peace | Equality | Integration | Volunteering | Legislation |

| 2 | Educatiob | Share ideas | Learn | Sociality (?) | Politics |

| 3 | Love people | Care for others | Solidarity | Good behavior | Cleaning |

| 4 | Rules | Society | Order | Commitment | Rules |

| 5 | Education | Respect | Order | Liberty | Fraternity |

| 6 | Education | Future | Participate | Environment | Human |

| 7 | Society | Justice | Coherence | Behaviors | Well Being |

| 8 | Help | Duties | Rights | Rules | Cooperation |

| 9 | Respect | Rights | Duties | Obligations | Rules |

| 10 | World | Nature | People | Rights | Duties |

| 11 | Humanity | Accept differences | Inclusion | Interpersonal network | Oportunities |

| 12 | Respect | To preserve | Contribute | Inovate | Accept |

| 13 | Justice | Equality | Work | Health | Fraternity |

| 14 | Rights | Humility | Social differences | Education | Education |

| 15 | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 16 | Character | Personality | Objective | Experience | Local |

| 17 | Good citizen | Look at each other | Responsible | Preserve | Respect the elderly |

Source: Author's own.

As can be seen, 80 words were identified that define “Citizenship” for students/prisoners, initially grouped into 54 different words, thus obtaining more than 40% similarity in a group of 16 people who responded.

The dynamic aimed to identify some patterns of attitudes and behaviors, which, influenced by the knowledge built up over time, could guide the debate on environmental issues more directly related to the central theme of the course: environmental citizenship. As stated by Doménech, López and Velasco (2011), much of the information obtained by this semantic method allows for further intervention measures for a defined social reality.

As established in the methodological proposal, table 4 presents the SAM set and its other three accompanying values.

Table 4 SAM set of the main defining words of “Citizenship” (Semantic Weight and Distance)

| SAM | Value J | PS | % | DSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | 17 | 100 | 0% | Education |

| 2 | 14 | 82.4 | 17.6 | Society / Humanity | |

| 3 | 14 | 82.4 | 17.6 | Rights | |

| 4 | 10 | 58.8 | 41.2 | Respect / To respect / Elderly | |

| 5 | 10 | 58.8 | 41.2 | Duties / Obligations | |

| 6 | 9 | 52.9 | 47.1 | Good Citizen / Citizen with others | |

| 7 | 9 | 52.9 | 47.1 | Justice | |

| 8 | 9 | 52.9 | 47.1 | Rules / Compliance with Rules | |

| 9 | 9 | 52.9 | 47.1 | Good Behavior / Behaviors | |

| 10 | 8 | 47.1 | 52.9 | People / Loving people | |

| 11 | 8 | 47.1 | 52.9 | Equality | |

| 12 | 7 | 41.2 | 58.8 | Accept Differences | |

| 13 | 6 | 35.3 | 64.7 | Order | |

| 14 | 6 | 35.3 | 64.7 | Preserving / Preserving the Environment |

Source: Author's own.

The previous table shows the values obtained when processing the information offered by students/prisoners, which suggests an analysis before launching the potential conclusions derived from this semantic test incorporated in an educational experiment in a prison environment. An element that confirms the purpose of bringing higher or basic education to a country's prison and the penitentiary system is that it, “education”, is seen by prisoners as a defining element of Citizenship. Not only does coincide with the sometimes empty speech of some political leaders when referring to the importance of education for a nation, sometimes without connection to the imaginary of those who are suffering the consequences of their behavior, finding themselves in a situation of deprivation of liberty. Adding the PS of the first three defining elements of citizenship (Education 17 e, Society / Humanity and Rights 14) the total is 45 points, thus occupying almost one-third of the participants' mental semantic space, with emphasis on “education” with 20 %, 85 points, in the supposed case that everyone had placed such an element in the first hierarchy (17x 5).

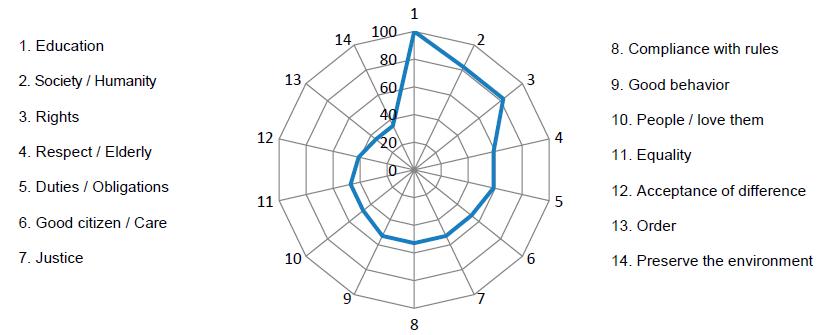

To further this last observation and make a final analysis of this dynamic, figure 1 represents all the distances between the defining words, starting from the word “Education” which with 17 points of PS was the most identified with the central word “Citizenship”.

Source: Author's own.

Figure 1 Quantitative semantic distance (DSC) (based on Doménech, López e Velasco, 2011)

Figure 1 shows graphically the results of its corresponding table 4. Both highlight the 14 highest values given to the defining words of the central theme “Citizenship”. It is, therefore, the SAM value. The concepts that make up this value impress by the importance they have to build “Citizenship”, which is intended that men and women who make up society enjoy this citizenship, together with inmates are also part of that society. Simultaneously, the result is impressive because such concepts in the SAM set reached a high value of their PS, which in turn influences their semantic distance, translating into homogeneity of thought among the participants in the dynamics (semantic test).

So, not only was there a certain homogeneity among students/prisoners about the central theme, although the rest of the elements listed as defining the “Citizenship” concept isn't expected to be spontaneously mentioned by a group of people who are punished for society itself with the suppression of its freedom, isolated most of the time from national development and subjected to a series of restrictions for security reasons. All of these elements allow us to conclude that it is worth reinforcing the defense of the right to education throughout life, regardless of the time when a convicted person has to find themself suppressed from this intangible asset, their freedom.

5 Final considerations

Like all scientific experience, in Education as well as in other social sciences, there is a clear objective that guides all the work described here, from its design to its evaluation. In this case, it was an attempt to evaluate a variation included in a previously tested pedagogical model, with the participation of individuals who attend higher education in a situation of seclusion, seeking, as in other studies carried out and referred to in this work, to create dynamics that are motivating and that offer students/prisoners opportunities to prepare for their return to society.

The results produced in this project brought very interesting conclusions, reinforcing the idea that it is worth investing in the education and training of professionals to wor with the population deprived of liberty. If the human being is capable of destroying nature in search of gold, then it is worth panning to rescue other human beings and return them to society.

The reaction of the participating group to environmental-participatory specific issues introduced by the dynamics seems to have demonstrated that the pedagogical model developed and tested by Dias-Trindade and Moreira (2019) and Moreira and Dias-Trindade (2020) is adapted to different dynamics and which still allows us to present a mature notion of what modern society should be, as well as indicating the importance that human activities have for the construction or destruction of Man-Nature relations.

The possibility of interaction with students/prisoners in person and extending the debates and discussions beyond the prison walls, through the digital signal, reinforces the educational possibilities, allowing those who feel more comfortable with face-to-face dynamics to interact in these moments and that others who prefer digital environments can also be involved actively.

Both the pedagogical model used and the activities evaluated proved to be an incentive for those who, dedicated to education, will continue to make efforts to educate and train for the return of this excluded population to contemporary society.

The analysis of the results was carried out separately according to each dynamics, having been obtained, in each case, two groups of results that were presented on a virtual platform, for the knowledge of students/prisoners and further discussion. As can be inferred, the inclusion of such dynamics, in addition to not obstructing the normal performance of the programmed activities required by the model used, proved to be a valuable material for 1) enriching the debate on the virtual platform; 2) to get to know each participant better during the face-to-face sessions and, 3) as a last, but not measurable value, to have the motivation to continue efforts to defend training and education in prisons, at least, as recommended by the Council of Europe (2013 ) and UNESCO (2010) - since a portion of all prisoners, through lifelong education, have means and moral desires to be reincorporated in society, as a second opportunity, and preferably with environmental and citizen awareness.

The quality of critical positions, the self-criticism presented in the virtual debates and the interaction between the participants, renew the faith that educators must remain firm in the purpose of rescuing those who want to contribute to their return to society.

With this study, we conclude that the construction of citizenship and natural laws have an intimate relationship; that the prison ecosystem, even if it seems utopian, can be converted into an ecosystem, like the natural one, that produces benefits for all parties, without having to trample human rights and thus facilitate an effective transition of resocialization of an excluded population.