Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação & Formação

versión On-line ISSN 2448-3583

Educ. Form. vol.8 Fortaleza 2023 Epub 23-Feb-2024

https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v8.e11458

Article

The creation of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo for the education of women

3Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

4Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

O artigo resulta da investigação sobre a Escola Doméstica de Nossa Senhora do Amparo, fundada em janeiro de 1871, na cidade de Petrópolis, que tinha como premissa atender a meninas pobres, órfãs e desvalidas. O objetivo geral é analisar as expectativas da formação confessional feminina para a infância desvalida, moldada no interior daquela instituição. Em um plano mais específico, o estudo propõe-se a investigar a educação feminina católica e suas concepções transmitidas desde a infância; as práticas pedagógicas educativas produzidas no interior da escola; e a cultura material escolar católica como uma construção que se manifesta de diferentes formas. Trata-se de uma pesquisa histórica, cujo corpus documental é constituído, sobretudo, pelo acervo existente no interior da escola, em um arquivo intitulado “Sala-Museu”. Assim, o estudo configura-se em uma contribuição para a história das mulheres das camadas mais desfavorecidas da população, cujos registros de suas práticas educacionais ainda se encontram silenciados.

Palavras-chave formação de mulheres; escola confessional; escola doméstica; Nossa Senhora do Amparo.

O artigo resulta da investigação sobre a Escola Doméstica de Nossa Senhora do Amparo, fundada em janeiro de 1871, na cidade de Petrópolis, que tinha como premissa atender a meninas pobres, órfãs e desvalidas. O objetivo geral é analisar as expectativas da formação confessional feminina para a infância desvalida, moldada no interior daquela instituição. Em um plano mais específico, o estudo propõe-se a investigar a educação feminina católica e suas concepções transmitidas desde a infância; as práticas pedagógicas educativas produzidas no interior da escola; e a cultura material escolar católica como uma construção que se manifesta de diferentes formas. Trata-se de uma pesquisa histórica, cujo corpus documental é constituído, sobretudo, pelo acervo existente no interior da escola, em um arquivo intitulado “Sala- -Museu”. Assim, o estudo configura-se em uma contribuição para a história das mulheres das camadas mais desfavorecidas da população, cujos registros de suas práticas educacionais ainda se encontram silenciados.

Palavras-chave formação de mulheres; escola confessional; escola doméstica; Nossa Senhora do Amparo.

El artículo es resultado de una investigación sobre la Escuela Doméstica de Nossa Senhora do Amparo, fundada en enero de 1871, en la ciudad de Petrópolis, cuya premisa era atender a niñas pobres, huérfanas y desfavorecidas. El objetivo general es analizar las expectativas de formación confesional femenina para la infancia desfavorecida, configuradas al interior de esa institución. A un nivel más específico, el estudio se propone investigar la educación católica femenina y sus conceptos transmitidos desde la infancia; prácticas pedagógicas educativas producidas dentro de la escuela; y la cultura material de la escuela católica como una construcción que se manifiesta de diferentes maneras. Se trata de una investigación histórica, cuyo corpus documental está constituido, sobre todo, por el fondo existente en el interior del colegio, en un archivo titulado “Sala-Museo”. Así, el estudio constituye un aporte a la historia de las mujeres de los sectores más desfavorecidos de la población, cuyos registros de sus prácticas educativas aún son silenciados.

Palabras clave formación femenina; escuela confesional; escuela doméstica; Nossa Senhora do Amparo.

1 Introduction

The historic center of Petrópolis, a mountainous city in the State of Rio de Janeiro, has a school with an imposing facade that covers almost an entire block- Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo. Founded on January 22, 1871, by its creator, João Francisco de Siqueira Andrade, also known as Father Siqueira1, Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo aimed to educate orphaned and poor girls.

The poor and helpless childhood in Brazilian society throughout the imperial period was a social problem denounced, questioned, debated, and documented in various 19th-century documents (Stamatto, 2017). The orphans were children of any age who had lost either or both parents. On the other hand, a helpless child was materially poor but had the support of someone in their family. Chaves et al. (2003, p. 88) states that “[...] girls whose mothers, relatives, authorities, or other individuals sought an orphanage for their care found themselves in different situations of neglect or abandonment”.

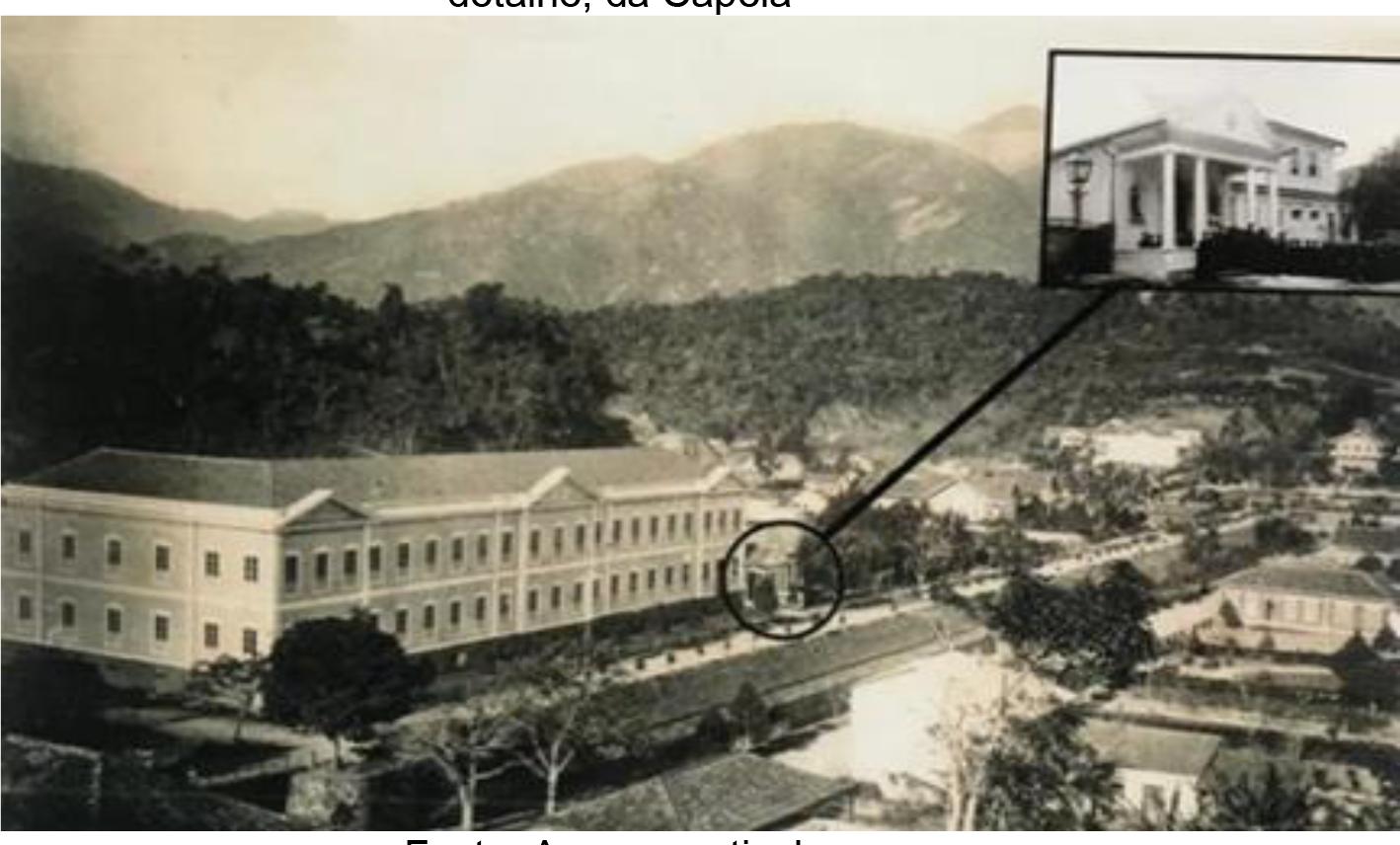

To start the construction of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, father Siqueira acquired, respectively, on April 30, July 17 and September 11, 1869, the plots numbered 192, 191/189 and 190, located at the intersection of one of the main avenues of Petrópolis. The architecture designed and built followed the neoclassical pattern prevalent at that time, with buildings in the shape of an "L." The funds raised for both land purchase and the construction were collected from donors and benefactors, some with extensive correspondence with Father Siqueira, preserved to date. Figure 1 below shows the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo shortly before its inauguration.

Source: Private collection.

Figure 1 Photograph of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo in 1870, with the enlargement, in detail, of the Chapel2

Currently, the facilities preserve the original features from the early period, despite its expansions, constituting a secular institution that, since the 1870s, has had the mission of educating women. However, more than 150 years later, the ideals and prescriptions of Father Siqueira can only be found nowadays in the "Sala-Museum" (Museum room).

The Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was established as a place for poor girls to access education, food, clothing, and to learn a trade suitable for women, among other opportunities within the grand architectural building. The primary role of the school was to prepare women so that, in the future, they could use the knowledge gained there to earn their own livelihood. In this perspective, the mission of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was to ensure that, beyond education, the students could lead their lives through their work, steering clear of the possibility of "a life of sin", after leaving school (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014).

The school thus had the dual attribution of training and educating women for their designated social roles. The architecture, which stimulated such task, was designed to meet physical, intellectual, and moral needs, blending the characteristics of conventual institutions with those of a strict female boarding school. The educational programs implemented were not only teaching methods and techniques but also ethical, moral, and religious principles for the formation of Catholic women. According to Julia (2012), the educational actions within the architectural monument, the school culture permeating the learning environments, rituals, forms of organization and management in addition to curriculum systems were directed towards the overarching goal of religious formation.

The girl’s daily routine at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was grounded on the pillars of religiosity, submission, obedience, and preparation for work-based learning. Rizzini and Pilotti (2009) highlight that, while there was an imposition of educational models in the asylums, there also emerged fields of negotiation due to the pressures and engendered forms of appropriation. The institution followed daily conduct norms legitimized by its statute/regulation, but other educational practices arose based on the needs imposed by daily life.

Protecting, supporting, and caring for childhood, especially for the poorest and most deprived girls introduced early into the "[...] labor world, especially in factories and workshops engaging in risky activities" (Camara, 2010, p. 221), was the main concern of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo from its inception. Its founder tirelessly campaigned within his social network to obtain donations for its achievement.

It's worth noting that the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo is the country's first asylum-school of national origin, founded by a Brazilian priest to shelter poor and orphaned girls. The school is also the first for poor girls established in the city of Petrópolis, with the purpose of not only protecting and instructing them but also enabling them to live dignified lives in the future.

Its creation is part of a movement that began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, involving Catholic confessional schools founded in Brazil by different religious congregations. The aim was to educate children and the youth, particularly girls, to become good Christians and pass on this devotion to husbands, sons, and daughters, while promoting an exemplary feminine standard.

As one of the pioneers of this model, the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was "closed in," meaning there was very little contact between the resident students and their parents or relatives-a form of control and oppression directed to women of that era. According to Vasconcelos and Leal (2014), this institution can be considered a classic example where education was a way to "shape" women according to the standards of femininity and submission required.

Considering the above, our article aims to analyze in-depth the expectations of confessional female formation for deprived childhood, shaped within the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo. Specifically, the study seeks to investigate Catholic female education and its conceptions passed on since childhood, the educational pedagogical practices produced within the school, and the Catholic school material culture as a construction that is manifested in various forms.

This involves presenting some of the results which are part of a broader historical research (Tavares, 2022), whose documentary corpus is primarily constituted by the collection within the school, in an archive titled "Sala-Museum," complemented by other sources obtained from institutions such as Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Hemeroteca Digital Brasileira, Arquivo Nacional, and Arquivo Histórico da Diocese de Petrópolis. Figure 2 below shows the "Sala-Museum".

Source: Private collection.

Figure 2 Photograph of the "Sala-Museum" with the archive of documents of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo

The "Sala-Museum" consists of horizontal display cases containing original documents from the time of the school's creation, such as certificates, diaries, epistles, dismissal letters, reports, photographs, among other papers. Particularly noteworthy is the Opúsculo sobre a educação (Pamphlet on Education), one of the manuscripts written by Father Siqueira, drafted in Petrópolis on December 8, 1877, which aimed to present his ideas on education and religion for the benefit of disadvantaged girls, and its transcription constitutes one of the main sources for this study.

Also serving as relevant research sources are the enrollment books, as they have crucial information to understand who the girls welcomed into the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo were. Each individual student enrollment record included data such as previous residence, house number, parish, day, month, and year of birth, registration book and page; day, month, and year of vaccination, as well as the name of the "doctor" and the registration book and page. It was also noted whether, upon entering the school, the student had brought any trousseau, who had recommended her, that is, "protected by the lady," residing on the street, number, and parish. This book, on each individual page, also has details about the students' withdrawal, such as: left on the day, month, and year, at whose request, for what type of occupation, for example, as a companion or employed in someone's house, with a contract and registered on which page of the contract book. In case of leaving to get married, it was reported whom she had married with, and the marriage book and page were also recorded. There were also those who passed away, and this was registered with the day, month, and year, as well as the death book and page. Therefore, "[...] the value of these sources is undeniable, as they emerge out of the silence of boxes and trunks, legitimating the historian to consider them, in their disjointed traits, as clues to the ways of living and understanding daily life" (Cunha, 2019, p. 103).

As it is essentially a historical-documentary research, it became necessary to contextualize and adapt each typology of document to be examined to the delimitation of the topic, considering that the protagonists of the investigation are women shaped within a school, whose formative experiences are centered in the nineteenth century. Thus, the data obtained from documentary sources were coordinated with content such as educational legislation of the period, school regulations, statutes, founder's egodocuments, among other archives.

The collection of the "Sala-Museum" was investigated and previously cataloged to record the sources necessary for the study (Heymann, 2012). According to Cunha (2015, p. 293), "organizing and safeguarding" collections "[...] is characterized as a driving force to combat forgetfulness through preservation practices that researchers in the history of education in Brazil engage in with dedication and seriousness." Mogarro (2005, p. 71), in turn, emphasizes that "[...] school archives raise deep concerns regarding the safeguarding and preservation of their documents, which constitute fundamental tools for the history of the school and the construction of educational memory."

Along this line, the existing archives at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo served as guiding landmarks in conducting the methodological procedures of the study, considering that the evidence emerging from the sources outlined significant aspects of the girls/women at that space/time, notably in the formation environment which they lived in.

2 The Formation of Girls: Wives, Mothers, Servants, or Teachers

Educating poor, orphaned, and disadvantaged girls during the nineteenth century so that they could change the course of their own lives was a challenging task. Del Priore (2000) points out that daughters, whose parents were poor, were unaware of how a woman could make a living through honest and persevering work, and further adds that many, due to lack of choices, were drawn into licentious living. On the other hand, Perrot (2019) also observes that various women throughout history sought emancipation, whether through education, knowledge, and/or work.

Offering both education and job training in the same institution and associating all of this with the principles of the Catholic religion, with the additional expectation of increasing the chances for women to support themselves, was quite distinctive for the time, the 1870s. However, this was coupled with a rigorous period of educational and religious formation during which power, control, and surveillance would be constantly exerted over the residents.

At the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, every detail of education was conceptualized by Father Siqueira so that poor, orphaned, and disadvantaged girls could have some prospects according to their abilities, as evidenced in his personal correspondence. From the organization of daily life, studies, subjects taught, to the housework to be performed by the girls, everything was carefully thought out and recorded by Father Siqueira (1877): "[...] all of you should prepare yourselves to make a living out of your work, either as servants or housekeepers, based on the system followed in Europe, or as teachers for those of you who qualify for teaching, or even by constituting a family through marriage."

Various documents on the girls’ education who lived at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, especially the priest's egodocuments, demonstrate his idea that "[...] the poor woman [can become] not only a good and future wife but also a worthy employee in the sanctuary of families, as well as helping the government in the direction and governance of schools and asylums that will soon be created throughout the countryside" (Newspaper O Mercantil, 1875). Thus, the students were trained to "transmit" the values they learned within the school, placed in situations designed according to the future destined for each one of them: to become mothers, wives, servants, teachers, and even nuns, as it happened to some who took vows in the congregations that successively administered the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo 3.

The girls were divided into classes based on age and aptitude, meaning those demonstrating higher abilities ascended to a higher level of education, guaranteeing their future roles in society. For those who got average grades, only reading, spelling, and some elements of arithmetic were taught; for those showing unequivocal manifestations of "clear and perspicacious understanding," they were prepared to become future teachers. In some way, all engaged in practicing trades they were taught, and for those considered more intelligent, there was another destiny-teacher training. Still, all were educated to be good mothers for their families (Vasconcelos, 2020).

All students were taught domestic chores so that in their own homes, they could be good wives and mothers, or if employed as servants and companions, they would know how to manage a household. By organizing the school in this way, the founder's distinction was evident: those who stood out would "embrace teaching," and those who knew how to do good work would "hire their services." Thus, the school provided training based on the personal characteristics of each individual as the institution's purpose, according to the founder, was to give the "poor class" the conditions to pursue the occupation for which they had talent and intelligence for because until they completed their studies, "[...] they are not prepared; they lack a method of work and instruction in general," (Report, 1877).

In any case, the primary purpose of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was to educate girls so that, in the future, they could provide for themselves by working in family homes or schools. Therefore, the education offered consisted of learning systems which were capable of making women possessors of good manners, well-educated, capable of assuming the social roles allowed to them with modesty: as a wife, mother, servant or teacher. The school uniform itself was a symbol investing in the characterization of modesty and decorum, through covered and concealed bodies (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014).

In this regard, Lira (2009) emphasizes that in confessional schools, the shaping of expected behavior was also determined by the subjection of the body, ensured with clothing that covered and kept it hidden, such as cloaks, tunics, and habits. Clothing, behavior, and gestures were part of the religious archetype that shaped the body, whose influences would be felt in society beyond convents, impacting family environments and other institutions.

Inside the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, the daily school life , its practices, norms and conceptions evidenced a rigid system of order and discipline, ranging from the daily actions of hygiene, food and leisure to the classes themselves. The routine complied with a strict pattern of schedules and defined spaces, loaded with disciplinary and orderly content, characterized by a mechanism of surveillance, and marking of all actions, through the bell, which sounded with different rings for each task/shift to be performed.

When analyzing the Regulatory Decrees of the school at the time when the founder still guided the formulation of the curricular subjects to be taught, he defined Christian doctrine and sacred history as primordial disciplines for life and domestic arrangements and embroidery as the way to instruct the students for domestic chores. According to Mauad (2010), at the time, in the 1870s, the education of girls evidenced in the curriculum of schools began to present a set of differentiated disciplines, despite valuing manual skills, social skills, and needlework of all kinds. The knowledge instituted as disciplines at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo included moral, religious, intellectual, and physical education for the girls. The school curriculum was drawn up based on the purposes the school aimed for, focused on general education and religious formation, in addition to teaching female crafts, with the students being instructed in a dialogical order between theory and practice.

The idea was to provide an education that could clearly highlight aptitude and intelligence. Students who excelled were directed towards teaching, which also met another need to train qualified professors to teach at the school itself. Thus, the intention was that students who stood out in intelligence and aptitude for teaching would become professors and be kept in the house. This was a recommendation noted by Father Siqueira from the very beginning, as his goal in establishing the teaching staff.

The pedagogical action carried out within the school followed the principles of the Lancaster method, where students were divided into classes, using the more "intelligent" ones to assist those with less learning conditions, as well as those with aptitudes for teaching as assistants to professors.

Based on these assumptions, as the students grew older and completed their studies, they took over roles reserved for teachers, while many of them did not even leave school despite their age limit, having their new professions as teachers.

3 Daily Practices and Materiality: Waking Up, Praying, Studying, Working, and Sleeping

The school culture of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo preserved in the archives demonstrates several practices that express the way in which the girls were to be educated to live and behave in the nineteenth-century society. The world within the school walls followed an organization with unique characteristics, its own rituals, acts, and languages (Vasconcelos; Boto, 2020). Thus, day after day, morning prayers dedicated to the benefactors were held repeatedly, classes would begin, primarily focused on religion, followed by a curriculum aimed at domestic tasks, guiding the students to become mothers and household managers. They woke up, prayed, studied, worked, and slept, "[...] they all had to work. Various crafts would be taught, from cooking to music" (Correio Paulistano, 1870). This is how the daily life of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was described in the newspapers.

According to Alves (2010),from the facilities to the chalkboards, manuals, uniforms, school notebooks, writing utensils, and various materials, all bear marks of a past with its signs and meanings, which can reveal numerous traces for the reconstruction of an institution's memory (Alves, 2010). In the analysis of the daily practices of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, one relevant aspect observed was the use of uniforms as objects of standardization and formation. Through preserved photographs and materials, it is evident that the girls wore apparently ivory-colored uniforms with a detail on the collar in white fabric embroidered with lace. According to Ribeiro and Silva (2017, p. 577), "[...] the uniform is one of the material elements that comprise the school and its culture, materiality conceived here as one of the constitutive elements of school culture."

Source: Archive of the Sala-Museum.

Figure 3 Photograph of the students at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo with the uniform worn at the end of the 1870s

The uniform of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo observed in the photographs at that time reveals a sense of belonging in each girl from that group and demonstrates other possible interpretations that may be implicit in its use, in addition to the existence of symbols with distinct meanings. Among these meanings, it turns out that the use of the uniform was a form of controlling sexuality, as its purpose was to hide "[...] the young girls’ bodies, which was aligned with the requirement of a discreet and dignified posture" (Louro, 1997, p. 461 apudPoletto, 2020). Another important factor regarding the use of the uniform is the sense of identification and assignment of the students, who aesthetically represented the established models of docile, orderly, and productive girls.

In such context, teaching rules of civility was as important as grammar, history, and geography classes. The learning of civilized behavior played a relevant role in the child's good conduct (Cunha, 2013). "Writing well" was one of the topics deemed essential by Father Siqueira, who considered writing as one of the aspects of great importance for the girls at that time. According to the priest, handwriting was essential for a girl to succeed in her future life: both in domestic life with her family and as a teacher. To Souza (2009), the content of handwriting manuals, a basic subject in elementary education, often consisted of norms of civility and Christian doctrine. In this sense, calligraphic writing, in addition to guidelines to the tracing of letters, dictated good manners, instilling the idea of self-control as a precept of civility (Cechin; Cunha, 2007). Thus, handwriting manuals led the child and adolescent not only to have beautiful handwriting but also to reflect on issues of obedience and care, among other good manners, "[...] in order to make women good mothers, wives, and household managers" (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014, p. 15). Principles related to ethics, obedience, respect, and kindness were defined in the text, signaling towards a harmonious formation between morality and Christian virtues (Cunha, 2013). Civility manuals, therefore, allowed for the construction of a given social conformity in defined time and space, enabling civilizing models echoed in society as etiquettes designed towards the formation of a good, obedient and kind family girl, (Cunha, 2013). It should be pointed out that, by reading the composition and copying it into handwriting books, such content was internalized, in other words, the implicit civility rule ended up being learned.

In the same line, Boto (2017) emphasizes the disciplinarian (regulatory) nature as inherent to the school institution, having the principle of production and self-regulation of students as one of its pillars. At the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, the ringing of the bell, the lines for transfers, the silence, and even fear were aimed at civilizational control and discursive production around the girls. Escolano Benito (2017) addresses the issues of the empirical culture of the school as a space marked by a chain of ritualities: prayer time, mealtime, bedtime, talking time, playing time, etc., creating specific liturgies and reinforcing certain practices surrounded by civilizing discourse (Escolano Benito, 2017).

These practices, norms, and concepts revealed a strict system of order and discipline within the school, ranging from the daily actions of hygiene, food, and leisure to the classes themselves (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014). The rituals were part of the students' routine, and each ritual had its goal: "[...] kneeling meant showing devotion to someone superior; folded hands indicated supplication; lining up meant order/organization to present oneself to someone" (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014, p. 20); in other words, the repeated movements in the daily life of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo were characterized as symbols, not only of religiosity but also of the submission required from the community participants.

An example of the clear submission demanded daily was the audible signal, the bell, which marked the time for meals. At this ritualized moment, meals were eaten in absolute silence, to satisfy physical needs, in the dining halls; the food was based on a logic of non-waste and sacrifice, where everyone should eat and appreciate the food offered, under the penalty of being hungry (Vasconcelos; Leal, 2014). Ultimately, the girls were shaped daily at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, submitting to established practices and rituals to conform to the female standards of that time and of the school. These practices also highlighted submissive behaviors and reinforced the obedience they had to the founder and teachers, being considered forms of regulation that produce self-regulation (Elias, 2011). According to Vasconcelos and Leal (2014, p. 18), the "[...] goal was to increasingly move away from the sinful image of Eve and approach the immaculate image of Mary."

It can be said that the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, while operating according to the principles of its creation, had three layers of jurisdictions. The first layer was made up of how society at that time viewed women from the most socially and economically disadvantaged classes, leading them to what was expected: "[...] to be a good mother, a household manager, and a wife alert to her husband's determinations" (Vasconcelos, 2020, p. 108). The second layer consisted of Father Siqueira's decisions and choices for the school, proposing rituals inspired by educational programs he had seen in his pilgrimages and those he believed to be the best ones for women's education. And finally, a third layer was instituted by the daily interaction among the girls, the nuns and teachers, who also provided both implicit and explicit formative processes to the students.

In a way, these three forces interacting within the school were present throughout formative and civilizing rituals, whose common goal was for the inmates to become good family mothers, receive appropriate instruction for their ages, and be prepared for future obligations imposed by society at that time. From the time they woke up until bedtime, the girls were accompanied and watched, being led to behave according to the guidelines of the place.

4 Final remarks

"Declaring a place, a building or an object as being heritage, immediately changes the angle that one sees it; it allows and prohibits certain gestures" (Hartog, 2020, p. 46). When we look at the building of the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo nowadays, in its dimensions conceived 150 years ago, the uniqueness of its founder's ideas is evident, with all the implications and subjectivities that this type of construction raises: a man, in the 1870s, supported by donations and alms, managed to build, in just over two years, an institution of considerable proportions, with an ideology that spanned decades and reached hundreds of women in the region and beyond.

Father Siqueira's school is a monumental building in the city of Petrópolis, even by today's standards, it seems to be "frozen in time." A monument that went through geographical, economic, social, and climatic changes, and that preserves, in a quite well-maintained manner, the documentation involving the period of its creation as a girls' regular and boarding school, offering numerous possibilities to researchers nowadays. "Material culture involves two major interrelated elements: the facilities, or fixed artifact, and the multitude of movable artifacts inside and surrounding it" (Funari; Zarankin, 2005, p. 137).

By handling, reading, analyzing, and interpreting the documents in the "Sala-Museum," it is possible to understand that Father Siqueira's ideal was for the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo to play a formative role in the lives of the graduating students, leading them to provide for themselves. To accomplish that, he created and implemented a strict organization in the form of a girls' boarding school, with some conventual rules, where the girls were immersed throughout their education within the school. The disciplinarian nature of the work can be perceived in the rigor, silences, and schedules for waking up, eating, sleeping, talking, playing, praying, studying, etc., revealing absolute control over the students, their behaviors, and actions.

The discipline expected and aspired by Father Siqueira and the nuns of the congregations4 that worked at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo was controlled through a characteristic element of that institution, the bell, whose ring transmitted regulatory messages encoded through sound. This instrument sounded whenever a discourse needed to be produced. However, today, it is silenced in a display case in the "Sala-Museum," witnessing a past that challenges time.

Thus, the processes of schooling and the selection of knowledge to be studied based on personal aptitudes were applied to all students and filled with disciplinarian methods, producing girls which were educated through teachings derived from Catholicism and based on what was expected from women at that time, namely, to have good education and instruction to become good family mothers or make a living out of an occupation considered appropriate.

Chiozzini and Leal (2022), in a research that looked into the presence of black individuals at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, finds the existence of black and mixed-race students among the girls admitted to the institution, reinforcing the characteristics of the work envisioned by Father Siqueira in the context of the 1870s. The students included daughters of enslaved mothers who received the same type of education "[...] at a time when women’s education was still a subject of discussion and faced many criticisms" (Chiozzini; Leal, 2022, p. 18).

To sum up, we understand that sharing the results of this research contributes to the history of women from the most disadvantaged layers of the population, whose records of their educational practices, particularly those who were under the care of these models of asylum institutions, remain the most silenced.

1 João Francisco de Siqueira Andrade was born on July 15, 1837, in the city of Jacareí, in São Paulo. After the Paraguayan War, in which he served as a military chaplain, he was deeply moved by the situation of orphaned girls he met on his way back to Brazil. Upon arriving in Petrópolis, he decided to establish a school to provide shelter, education, and the learning of a trade to orphaned and destitute girls.

2 In the overlaid detail of this photograph, it is possible to catch a glimpse of the old Chapel that stood beside the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, a structure predating Father Siqueira's, where the inauguration mass of the institution took place.

3 At the time of its creation, the priest invited Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary to oversee the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo, a congregation of nuns of German origin that had been in Brazil since 1855, in Rio Grande do Sul. On January 10, 1871, the founding mother of the congregation, Bárbara da Santíssima Trindade, and sisters Isabel do Preciosíssimo Sangue, Maria de Jesus, Teresa dos Prazeres de Nossa Senhora, and Estanislau da Assunção arrived in the city of Petrópolis. The newspaper Correio Paulistano (1870) reported as follows: “Education, both spiritual and artistic, is entrusted to a Congregation of German ladies, specially hired in Germany by Reverend Father Siqueira".

4 For the outcome of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at the Domestic School of Nossa Senhora do Amparo and the formation of the new Congregation, refer to Leal (2017).

REFERENCES

ALVES, C. Educação, memória e identidade: dimensões imateriais da cultura material escolar. História da Educação, Pelotas, v. 14, n. 30, p. 101-125, 2010. [ Links ]

BOTO, C. Instrução pública e projeto civilizador: o século XVIII como intérprete da ciência, da infância e da escola. São Paulo: Unesp, 2017. [ Links ]

CAMARA, S. Sob a guarda da república: a infância menorizada no Rio de Janeiro da década de 1920. Rio de Janeiro: Faperj, 2010. [ Links ]

CECCHIN, C.; CUNHA, M. T. S. Tenha modos! Educação e sociabilidades em manuais de civilidade e etiqueta (1900 - 1960). In: SIMPÓSIO INTERNACIONAL DE PROCESSO CIVILIZADOR, 10., 2007, Campinas. Anais [...]. Campinas: Unicamp, 2007. p. 1-11. [ Links ]

CHAVES, A. M.; GUIRRA, R. C.; BORRIONE, R. T. M.; SIMÕES, G. A. Significados de proteção a meninas pobres na Bahia do século XIX. Pscicologia em Estudo, Maringá, v. 8, p. 85-95, 2003. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722003000300011. [ Links ]

CHIOZZINI, D. F.; LEAL, L. S. As alunas negras da Escola Doméstica de Nossa Senhora do Amparo (1889-1910). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 22, n. 1, p. e213, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v22.2022.e213. [ Links ]

CORREIO Paulistano, ed. 4172, v. 17, p. 1-2, 1870. [ Links ]

CUNHA, M. T. S. Acervos escolares: olhares ao passado no tempo presente. História da Educação, Rio Grande, v. 19, n. 47, p. 293-296, 2015. [ Links ]

CUNHA, M. T. S. (Des)arquivar: arquivos pessoais e ego-documentos no tempo presente. São Paulo: Florianópolis: Rafael Copetti, 2019. [ Links ]

CUNHA, M. T. S. Do coração à caneta: cartas e diários pessoais nas teias do vivido (décadas de 60 a 70 do século XX). História: Questões & Debates, Curitiba, n. 59, p. 115-142, 2013. [ Links ]

DEL PRIORE, M. O cotidiano da criança livre no Brasil entre a Colônia e o Império: história das crianças no Brasil. São Paulo: Contexto, 2000. [ Links ]

ELIAS, N. A Sociedade dos indivíduos. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2011. [ Links ]

ESCOLANO BENITO, A. B. A escola como cultura: experiência, memória, arqueologia. Campinas: Alínea, 2017. [ Links ]

FUNARI, P. P.; ZARANKIN, A. Cultura material escolar: o papel da arquitetura. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 16, n. 1, p. 135-144, 2016. [ Links ]

HARTOG, F. Crer em história. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2020. [ Links ]

HEYMANN, L. Q. O lugar do arquivo: a construção do legado de Darcy Ribeiro. Rio de Janeiro: Contracapa/Faperj, 2012. [ Links ]

JULIA, D. A cultura escolar como objeto histórico. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 1, n. 1, p. 9-44, 2012. [ Links ]

LEAL, L. S. Escola Doméstica Nossa Senhora do Amparo e o processo de escolarização de mulheres negras na Primeira República (1889-1910). 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação: História, Política, Sociedade) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação: História, Política, Sociedade, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2017. [ Links ]

LIRA, M. H. C. Academia das santas virtudes: a educação do corpo feminino pelas beneditinas missionárias nas primeiras décadas do século XX. In: SOUZA, E. F. (org.). Histórias e memórias da educação em Pernambuco. Recife: UFPE, 2009. p. 21-40. [ Links ]

MAUAD, A. M. A vida das crianças de elite durante o Império. In: DEL PRIORE, M. (Org.). História das crianças no Brasil. 7. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2010. p. 137-176. [ Links ]

MOGARRO, M. J. Arquivo e educação: a construção da memória educativa. Sísifo: Revista de Ciência da Educação, São Paulo, n. 1, p. 71-84, 2005. [ Links ]

O MERCANTIL, ed. 8, v. 19, p. 2, 1870. [ Links ]

PERROT, M. Minha história das mulheres. São Paulo: Contexto, 2019. [ Links ]

POLETTO, J. T. “Preparadas para a vida”: uma escola para mulheres, Colégio São José (Caxias do Sul/RS, 1930-1966). 2020. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2020. [ Links ]

RELATÓRIO. Escola Doméstica de Nossa Senhora do Amparo. 1877. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, I.; SILVA, V. L. G. Das materialidades da escola: o uniforme escolar. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 38, n. 3, p. 575-588, 2012. [ Links ]

RIZZINI, I.; PILOTTI, F. A arte de governar crianças: a história das políticas sociais, da legislação e da assistência à infância no Brasil. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2009. [ Links ]

SIQUEIRA, P. Opúsculo sobre a educação. [S.l.: s.n.], 1877. [ Links ]

SOUZA, A. W. S. Os manuais de caligrafia e seu vínculo com o desenho no Brasil do século XVIII. Sitientibus, Feira de Santana, n. 40, p. 39-58, 2009. [ Links ]

STAMATTO, M. I. S. Asistencia social educativa para la infancia desvalida (Brasil, 1822-1889). Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, Madrid, v. 75, p. 89-110, 2017. [ Links ]

TAVARES, M. C. C. A obra do padre Siqueira para a educação da pobreza: “a mais desvalida, a do sexo feminino”. 2022. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2022. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, M. C. C. Ensinamentos e contos: Maria Amália Vaz de Carvalho e sua estratégia para a educação da mulher. Revista Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 20, n. 67, 2020. DOI: 10.7213/1981-416X.20.067.DS02. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, M. C. C.; BOTO, C. A educação domiciliar como alternativa a ser interrogada: problema e propostas. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 1, n. 2014654, p. 1-21, 2019. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, M. C. C.; LEAL, M. J. S. C. Dos traços de pecadora aos modos recatados: a educação do corpo feminino. In: NADER, M. B. (org.). Gênero & racismo: múltiplos olhares. Vitória: Secadi, 2014. p. 14-41. [ Links ]

Received: July 09, 2023; Accepted: October 15, 2023; Published: December 11, 2023

texto en

texto en