Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Educação em Questão

versão impressa ISSN 0102-7735versão On-line ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.61 no.70 Natal out./dez 2023 Epub 06-Mar-2024

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2023v61n70id34240

Artigo

Intercultural dialogue based on an Erasmus Plus Project: student-centered learning

Prof.ª Dr.ª Márcia Lopes Reis Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (Campus Bauru e Araraquara, Brasil), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Escolar (Campus Araraquara), Grupo de Estudos da Infância e da Educação Infantil: Políticas e Programas, E-mail: marcia.reis@unesp.br

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0520-506X

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0520-506X

Prof. Dr. Macioniro Celeste Filho, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (Campus Bauru, Brasil), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação (Campus Bauru e Marília), Grupo de Estudos e Pesquisas sobre Cultura e Instituições Educacionais, E-mail: macioniro.celeste@unesp.br

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8798-9891

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8798-9891

Victor Bastos Ventura, Coordenador Discente de Gestão de Pessoas do Cursinho Pré-Universitário Ferradura –, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (Campus Bauru), E-mail: victor.ventura@unesp.br

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6851-621X

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6851-621X

2Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (Brasil)

The article aims to discuss the possibilities of internationalization university actions with intercultural practices inferred from the implementation of an extension project at a public university in the state of São Paulo in the context of an Erasmus Plus Project. It is theoretically based on interculturality as dialogue and communication among different cultures, recognizing diversity as a value in itself, according to Dussel (2016), Quiroz (2007), Santos (2006), among others. The case study was the methodology adopted and the units of analysis are the pedagogical formation courses implemented with the theoretical-practical foundation of the Erasmus Plus Project in the extension action Cursinho Pré-Universitário Ferradura (College Prep Course Horseshoe), at São Paulo State University (UNESP). The results made it possible to systematize evidence of collaboration between different cultures. The conclusion is that projects such as Erasmus, even if proposed unilaterally, make it possible to establish internal dialogues within the university and, externally, with other university institutions, from the perspective that the “different” can promote synergies and intercultural dialogue.

Keywords Active learning; Intercultural studies; Erasmus Plus; UNESP

O artigo objetiva discutir as possibilidades de internacionalização das ações universitárias com práticas de interculturalidade inferidas desde a implementação de um projeto de extensão de uma universidade pública paulista no contexto de um Projeto Erasmus Plus. Fundamenta-se, teoricamente, na interculturalidade como diálogo e comunicação entre diferentes culturas, reconhecendo a diversidade como um valor em si mesmo, segundo Dussel (2016), Quiroz (2007), Santos (2006), entre outros. O estudo de caso foi a metodologia adotada e as unidades de análise são as formações pedagógicas implementadas com a fundamentação teórico-prática do Projeto Erasmus Plus na ação de extensão Cursinho Pré-Universitário Ferradura, da Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP). Os resultados permitiram sistematizar evidências de colaboração entre distintas culturas. Conclui-se que projetos como o Erasmus, mesmo propostos de modo unilateral, possibilitam estabelecer diálogos internos na universidade e, externamente, com outras instituições universitárias, desde a perspectiva de que o “diferente” pode promover sinergias e o diálogo intercultural.

Palavras-chave: Aprendizagem ativa; Estudos interculturais; Erasmus Plus; UNESP

El artículo tiene el objetivo de discutir las posibilidades de internacionalización de las prácticas interculturales inferidas desde la implementación de un proyecto de extensión en una universidad pública de São Paulo en el contexto de un Proyecto Erasmus Plus. Se fundamenta, teóricamente, en la interculturalidad como diálogo y comunicación entre diferentes culturas, reconociendo la diversidad como un valor en sí mismo, según Dussel (2016), Quiroz (2007), Santos (2006), entre otros. El estudio de caso fue la metodología adoptada y las unidades de análisis son los cursos de formación pedagógica implementados con la fundamentación teórico-práctica del Proyecto Erasmus Plus en la acción de extensión Cursinho Pré-Universitário Ferradura (Curso Preuniversitario Herradura), en la Universidad del Estado de São Paulo (UNESP). Los resultados permitieron sistematizar pruebas de colaboración entre diferentes culturas. La conclusión es que proyectos como Erasmus, aunque se propongan unilateralmente, permiten establecer diálogos internos en la universidad y, externamente, con otras instituciones universitarias, desde la perspectiva de que lo “diferente” puede promover sinergias y diálogo intercultural.

Palabras clave: Aprendizaje activo; Estudios interculturales; Erasmus Plus; UNESP

Introdução

Dealing with interculturality seems to be a premise of the trends towards the internationalization of higher education and, at the same time, a challenge for institutions such as public universities, whose emergence has nothing to do with dialogues with distinct and different groups. More recently, it has become a relevant trend of the World Conferences on Higher Education, consolidated in Europe with the Bologna Process in 1999. This trend returns to the very origin of medieval universities, marked by an intentional westernization of this educational practice. Under these conditions, characterized by an intense informational and networked movement (Castells, 2000; Lojkine, 1995; Negroponte, 1990; Schaff, 1995), the international relations of university systems in North-South and South-South spheres represent the context of this article.

Based on these premises, to what extent can international cooperation projects, such as Erasmus Plus, promote internal dialogue within the very universities that are part of these actions and, at the same time, with other higher education institutions? What would be the possibilities of cultural appropriation of the foundations by the subjects involved in these projects? Thus, this article has the general objective of identifying the possibilities of intercultural dialogues when carrying out an international project, such as the Erasmus capacity building projects, when implemented in one of the Latin American educational institutions, specifically in a public, state university. Reflecting on these issues requires remembering the origins of Erasmus Projects. To this end, since 1987, the initiatives of the Association des États Généraux des Étudiants de l’Europe, founded by Franck Biancheri, have been important. He later became the president of a political party with intercultural characteristics – different ethnicities, gender and income at the end of the month – and continued to operate at European level, the Newropeans. Its political relevance should be remembered in supporting governments such as those of François Mitterrand (France) and Felipe González (Spain) and its developments such as the capacity building type project that continues to enhance actions such as the Erasmus Plus Student-Centered Learning Project (Erasmus+- SCL Project).

Specifically in this case to be studied, the Erasmus+-SCL Project represents a proposal that brings with it a relevant contradiction: the historical agents of education – teachers and students – seem to reverse their roles. This reversal occurs by centralizing the teaching and learning process on students, historically relegated to the role of passive people without any prior knowledge that would be of interest to the school, regardless of the level (basic or higher). The dialogues among the various higher education institutions that make up the Erasmus+-SCL Project represent the other dimension of interculturality to be addressed in this article from the perspective of the universities’ internationalization process.

The research: the case study of the Erasmus+-SCL Project in a community outreach program

The locus of this research is represented by university institutional spaces for intercultural dialogue, as the universities’ community outreach actions are usually characterized, including the Brazilian one, due to its 'Humboldtian' model. In this case, specifically, the selection of Cursinho Ferradura [Ferradura College-Prep Course] as a community outreach program to be the pilot in the Erasmus+-SCL Project is due to the fact that, institutionally, its main function is the preparation for passing the entrance exam and the appropriation of a university culture by individuals, historically excluded in the groups of black, brown and indigenous people who graduated from public basic education. These arguments justify this choice because considering diversity as a value in itself characterizes and differentiates this community outreach practice: since 2006, by opting to serve only these students from the city of Bauru (São Paulo) and surrounding areas, it has expanded even further the plurality of approaches in teaching and learning processes. Along with 34 other college-prep courses distributed across the other campuses of the “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” State University of São Paulo – UNESP – it represents a relevant success story: The Ferradura college-prep course has 160 students in the cities of Bauru and Pederneiras, in the state of São Paulo, managed by a group of teachers who are scholarship students from the institution itself. It is also worth noting that, in order to serve this audience which is external to the university, the selection of students has been carried out through a qualitative analysis, based on the student’s address and their family's monthly income. The Ferradura college-prep course has achieved an average approval rate of around 35% of applicants from different selection processes for universities, which represents a success taking into consideration the unequal initial conditions of arrival of these students. This context, per se, constitutes a contradictory situation, taking into account that, being scholarship students, teachers at the college-prep course, they provisionally assume the condition of teachers. At the same time, in fulfilling this role, they begin to appropriate a teaching culture along the lines of student-centered learning, as a result of the training in the Erasmus+-SCL Project model. These training courses imparted by UNESP’s permanent professors involved in this Erasmus Project are part of this internationalization action centered in intercultural practices as one intends to show in its internal (aimed at the institution itself -UNESP - in this case) and external (with teachers and students from the other countries involved in the Erasmus+-SCL: Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru) dimensions1.

It was thus carried out, like all UNESP’s community outreach actions, an 'action with research and research in action' (Barbier, 2002), whose implementation stages were: a) selection of the Ferradura college-prep course as the 'case' to be studied; b) carrying out training for teachers who are undergraduate students; c) evaluation of evidence of changes in the perception of researchers involved in the Erasmus+-SCL Project based on responses to different forms delivered to teachers and scholarship students at the Ferradura college-prep course. For teachers, two questions: what did they begin to know about student-centered learning and what changes were observed in the actions carried out. For students, just one question, dealing with the argument for learning to be focused primarily on them.

It is noted that the qualitative methodology chosen was the analytical case study (Yin, 2001, Ludke; André, 2013). One expected, thus, to analyze in what way the subjects who are teachers and students at a Brazilian public university would have appropriated in their planning and implementation principles methodologies and actions, characteristics derived from the concept of student-centered learning, as proposed in the objectives of this more comprehensive – Erasmus +-SCL Project.

In addition to being a methodological option, case studies have represented relevant teaching material in teacher training processes. From the perspective of authors such as André (2005), Shulman (1992) and Merseth (1996), case-based learning helps these education professionals to develop skills such as diagnosing problems, recognizing multiple influences and perspectives and involvement in the exercise of suggesting and analyzing possible solutions.

Thus, the study took place in the first year of implementation of the Erasmus+-SCL Project, effectively, from March to November 2021. The subjects of the case study included five university professors, representing the areas of Education and Environmental Engineering, and twelve undergraduate students from different areas of knowledge, who played concurrently the role of undergraduate students and scholarship holders playing the role of teachers in UNESP’s Community Outreach Program, the Ferradura College-Prep Course, in a macro-sociological context of internationalization of university actions.

Interculturality in the universities’ internationalization processes

Was there concern about equitable cultural exchanges during the internationalization processes of European and Latin American universities in recent decades? It does not appear to have been a relevant priority. Even so, studies on the processes of internationalization of educational models are not recent, and there is even an area of knowledge dedicated to such studies, that of Comparative Education. One does not intend to discuss, within the scope of this article, something as comprehensive as that. However, as a basic context for situating the study presented here, it is worth pointing out that it is connected with previous studies, which analyzed and criticized international projections and the consequences of European university reorganization at the end of the last century. Known as the Bologna Process, the international conventions signed in that city in 1999 coincide with the Delors Report and have decisively influenced debates on Higher Education around the world:

One of the objectives of the Bologna Process is the global reach of the reform. To this end, still in 2000, the Common Higher Education Space of the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean was created, with the aim of establishing convergence measures between Latin American and Caribbean higher education systems with the structure proposed for the European Higher Education Area (Siebiger, 2018, p. 250).

The historical European leadership in Higher Education in Latin America can be traced back to the immediately preceding periods, such as those of university reforms in different Latin American countries, especially in the 1960s. Note the absence of intercultural practices:

When it comes to cooperation, it cannot be forgotten that the current European model has been applied in many Latin American institutions since the 1960s and, in some, since the 1950s. The starting point for equitable intercontinental cooperation could be to observe how it was applied in institutions as diverse as the University of Costa Rica, Los Andes, Concepción, Brasília and Minas Gerais. The credit system, somewhat pragmatic and useful, in Brasília, in the 1970s, allowed students to have a flexible curriculum and organize their study time according to their availability (Mello; Dias, 2011, p. 416).

The credit system that permeates the quantification of school time in Western university curricula has currently been internalized to such extent that it is not surprising. However, it resulted from a one-way, North-South influence from previous reorganizations of universities in Europe and the United States. This fact is mentioned to highlight that Brazilian universities appropriated this system, often converging with international contributions from foreign university experiences. With the globalization of capitalist relations, this seems to be inevitable (Chesnais, 1996).

Derived from the Bologna Process, the international dissemination of concepts such as competencies and skills went beyond university debates and mobilized educational proposals from Basic Education upward. This phenomenon began to overwhelmingly affect Latin America. The critical reaction to the indiscriminate import of themes, terms and concepts pertinent to the predominantly European educational debate was also relevant and highlights the absence of an intercultural practice: the incisive trend of European university curriculum homogenization caused debates, consensuses and dissent among the stakeholders from different institutions involved. This is partly because the proposal to standardize curricula to facilitate student mobility (inspired by the 1999 Bologna Treaty) and employability skills seemed to be considered more 7 important than education geared towards citizenship in European and Latin American higher education reforms in the first years of the current century:

A basic concept that has been little studied and analyzed so far is that of skills. It appears coupled with the idea of comparison and equivalence between studies and the importance of employability and the job market. The aim is to homogenize titles and certificates, whose professional skills become standardized and are evaluated according to similar procedures, everywhere. Skills do not encompass what the 1996 Delors Report proposes, which emphasized the importance of skills for citizenship. They refer exclusively to the current job market. The focus is on a university rooted in the business world (Mello; Dias, 2011, p. 419-420).

These criticisms of the import of models based on competencies and skills, in a one-way North-South movement, as if they were neutral concepts, pointed out how the inversion of learning concepts caused, as in a popular saying, the tail to wag the dog. That is, one defined the professional skill needed at the end of learning for a role in the job market and, in reverse order, the curriculum that would provide such skill was designed:

In short, learning outcomes are defined for each course, which comprise what students will be able to do at the end of a given training cycle/process. Based on the definition of these outcomes, general skills (common and transferable to any course or program) are created, subdivided into instrumental, interpersonal and systematic. And the specific ones (related to the course or program area), classified as professional, academic and social, which refer to theoretical-practical and/or experimental knowledge and skills specific to the area. The skills must therefore contribute to achieving the established learning outcomes and, these, to achieving the proposed meta-profile. [...] Therefore, it is the professional profiles that determine the meta-profile, the learning outcomes and the relevant associated skills. For each learning outcome, one selects from the matrix which skills should be acquired and developed. And, instead of course or program objectives, one has the definition of these elements, which, in turn, determine the selection of content to be included in the curriculum (Siebiger, 2018, p. 252).

In this system, the university was instrumentalized as the executor of student professionalization in Higher Education, without paying attention to the other social responsibilities of the Brazilian university in a context of marked social inequality:

As can be seen, taking into account that the objectives for higher education are restricted to preparation for professional practice in a given society scenario, it would be up to the university to simply adapt, no longer existing as an autonomous institution, but at the service of these objectives. Therefore, there is also a redefinition of the university, which must become a center for training professionals, researchers and producing research for the knowledge society, giving up its other dimensions related to the cultural, human, political and critical education (Siebiger, 2018, p. 257).

Resulting from the Bologna Process (1999), criticism of the subordination of European university systems to business interests in the training of qualified labor overshadowed the possible positive contributions that the reforms could provide:

Thus, one asks oneself what does it mean to be a citizen in this proposed scenario? Becoming a citizen, in this scenario, means acting as an up-to-date, competent professional capable of being absorbed by the productive environment. It means apprehending, developing and applying knowledge, skills and attitudes in an arena with previously established rules, in a society scenario with a single bias of academic-social ethos, in which the social relationships provided through higher education practically boil down to relationships of a professional nature. In this perspective, the path that leads to the consolidation of the knowledge society is a naturalized and irreducible process, presenting itself as the only possible alternative for the development of society (Siebiger, 2018, p. 255).

However, would it be possible to establish an intercultural dialogue mediated by educational procedures resulting from the Bologna Process? Not even the most radical critics deny that this is viable:

It is in Latin America that there is greater awareness of the need to maintain the idea of quality and relevance as interconnected concepts, and that relevance does not exist without the search for solutions to society's major problems, such as the eradication of poverty, intolerance, violence, illiteracy, the deterioration of the environment, the increase in discrimination of all kinds, among others – all millennium goals, defined by the United Nations in the year 2000. The creation and consolidation of a Latin American network of socially responsible knowledge, materialized by a dynamic and integrated international network of training, research and innovation, with the aim of social inclusion, represent, thus, the region's biggest challenge for this century. The European Higher Education Area, as a result of its vices and virtues, can be an excellent laboratory for Latin America, with which it can collaborate, without representing a model to be faithfully followed (Mello; Dias, 2011, p. 431).

Alex Mello and Marco Dias (2011) and Ralf Siebiger (2018), previously mentioned, do not see the possible contributions that the internationalization processes of European university systems can provide us, as long as we effectively preserve our universities as democratic locus of social and cultural diversity. This possibility remains an open question that reaffirms the need for multipolar cultural exchanges:

A question that cannot be answered is whether we are returning to a system of equivalence of all systems with the European system and, through this, with the United States system. One rejects any democratic system of recognition of studies and diplomas in which all parties have equal rights and in which the diversity of systems corresponds to the cultural and social diversity of the different regions of the world (Mello; Dias, 2011, p. 427).

With the above question in mind, but with a view that is not primarily averse to the possibilities of intercultural dialogue and learning from other people's experiences, is that the authors of this article participated in the Erasmus+-SCL Project. The various Erasmus projects previously carried out connected to Latin American universities result from proposals for the internationalization of the European Higher Education, resulting from the Bologna Process. Given this scenario, what interculturality are we dealing with when we consider the Erasmus capacity building projects?

Defining interculturality

Initially, these training processes can be typified by interculturality, characterized in this article based on Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2006, p. 462), for whom convergence in terms of culture, “[...] is very difficult to achieve, not only because the capacity for intercultural translation of themes is inherently problematic, but also because in all cultures there are themes that are too important to be included in a dialogue with other cultures”. Based on this assumption, in the context of human rights, Santos develops a concept of emancipatory multicultural policy whose transcultural imperative would be summarized as follows: “[...] we have the right to be equal when difference makes us inferior; we have the right to be different when equality characterizes us” (Santos, 2006, p. 462).

It is observed here that the author moves through multiculturality (a set of cultures located in parallel, without dialogue between them) and arrives at transculturality (understood as the adoption of other forms of culture that would cross the limits that each of them has). For this article, we have used, from Santos (2006), the horizontal and synergistic interaction that cultural dialogues provide. This conceptual choice refers to culture as capital along the lines of Bourdieu (1989), for whom the set of ideas and knowledge that people use when participating in social life can be exchanged, in short, dialogued. Thus, everything from the rules of etiquette to the ability to speak or write can be considered cultural capital. Even if Bourdieu was not interested in dealing with interculturality, one observes that it would be the absence of this condition that would largely explain the success of the educational system: the individuals who appropriated the dominant culture, that is, the amount of cultural capital, they tend to be from a privileged group that has access, aggravating the reproduction of social inequalities. In the words of Fanon (in Zibechi, 2018), interculturality would enable a decolonization of thought if we consider that ‘the colonized is a persecuted person who permanently dreams of becoming a persecutor’.

One adds to the definition of interculturality assumed here the perspective of authors such as Lopez-Hurtado Quiroz (2007) and Walsh (2009), considered in its central characteristic: interculturality as a set of possibilities for equitable dialogues between different ways of being, feeling and acting in the contemporary world. Whether related to people, interest groups, segments, social strata, institutions or countries that tend to result in synergies for the construction of other cultural practices. Dussel (2016), in turn, defines 'transmodern interculturality' on the one hand, as the relationship between intercultural dialogue and communication and, on the other, the search for understanding and collaboration between different cultures. These conceptual traits seem evident in the Erasmus+-SCL Project, as well as in the results of the case under study, the community outreach action carried out at the Ferradura College-Prep Course (Cursinho Ferradura).

Interculturality in the Erasmus+-SCL Project

In the specific case of the Erasmus Plus Student-Centered Learning Project discussed here, the actions used by those involved in the project allowed the reevaluation of the participants' knowledge, from an initial European proposal. Under the coordination of the University of Groningen (Groningen/ Netherlands), in addition to the São Paulo State University - UNESP (São Paulo/Brazil), together with the other higher education institutions participating in the project, mentioned previously, it was outlined a proposal for training and collaboration with a view to discussing the profiles of graduates from higher education programs and the methodologies adopted throughout the training to achieve the learning results. Erasmus projects, in their operating format since 1987, stem from the initiative and leadership of one European higher education institution – in this case, the University of Groningen (Netherlands) – which makes the proposal to a European Union Educational Commission, which, in turn, evaluates and funds the approved proposals. This organization that funds capacity building actions represents the first dimension of interculturality to be considered in the analyses discussed here: a model of exchange of students and teachers/professors inspired by the Bologna Pact (1999). To this end, the specific objectives of this Erasmus+-SCL Project are the construction of structural conditions for the mobility of teachers and students, with a view to improving the participants' profiles. The central premise is that the exchange of experiences of curricular structures enables the construction of knowledge flows, whose synergy accumulated by different university trajectories can result in intercultural dialogues. Therefore, the ways and times in which students learn, based on the planning of teachers attentive to the different conditions of students, in different curricular realities, occupy the centrality of this Erasmus+-SCL Project.

Thus, one observes the Erasmus+-SCL Project’s concern with the intercultural dialogue, since its initial proposal when dealing with the creation of a glossary common to the higher education institutions involved, called 'inter-conceptualization', as it defined words such as undergraduate studies, credit, learning objectives, teaching and learning results, among other concepts, in different ways. Once these concepts had been 'negotiated', each of the institutions of the Erasmus+-SCL Project began planning the training actions for the team of teachers and students, based on the learning results to be achieved, so that the profiles of graduates of the programs in the different countries are equally equivalent.

The active methodologies, hence the project’s name - 'Student-Centered Learning' - for the implementation of these training actions were chosen by the project proponent – University of Groningen, Netherlands – and represent the first dimension of interculturality to be considered in the analyses: that of the centrality of the university student in the learning processes, traditionally focused on teaching. It is widely known the traditional methodologies in which it is considered that 'a well-taught class would guarantee the student's learning', which Freire (1971) defined as 'banking education'. Thus, each of the higher education institutions participating in the Erasmus Plus Project, in different Latin American countries, developed training for teachers and students that revisit active methodologies, with the objectives of promoting changes in the emphasis of the teaching and learning process. At each general meeting, intercultural dialogue between teachers and students from different countries can be highlighted in structured working groups for training on: a) the learning outcomes proposed for the selected programs in the areas of Environmental Engineering, Health, History and Education; b) the roles of teachers and students in the Erasmus+-SCL methodology; c) the possible configurations of a student-centered class; d) the ways of evaluating students when adopting the principles of this methodology.

With a view to implementation in UNESP’s undergraduate programs in which the teachers/professors and students involved act, it was possible to carry out this 'case study' type research at the Ferradura College-Prep Course [Cursinho Ferradura], the place that played the role of 'pilot'.

Research results: evidence of an intercultural practice

The potential for identifying intercultural practices in the Ferradura College-Prep Course with the implementation of training actions resulting from the Erasmus+-SCL Project brings with it a plausibility that arises from its characterization: prioritization of assistance to historically excluded groups (black, brown and indigenous) and inhabitants of historically vulnerable territories, such as urban peripheries. Coming from public schools, access to university, which is also public, has been denied to these subjects, turning cultural difference into social inequality and inequality of opportunity. Thus, since 2016, by a collective decision of the groups of teachers/professors and undergraduate students involved in this community outreach program, the BBI groups (black, brown and indigenous) constitute the priority of interaction, materializing a set of affirmative actions that have been implemented as a public educational policy since 2001. Seen in this way, the selection of this research locus allowed for the observation of a dialogue between different cultural groups: on the one hand, undergraduate students who work as teachers at the Ferradura College-Prep Course and, on the other, the professors who work in undergraduate programs who, directly or indirectly, would influence the processes of understanding the principles of a pedagogical trend of the 'active methodologies' type, such as this proposed by a European project of an international and inter-institutional nature – the Erasmus+-SCL Project. Initially, in order to create an environment conducive to the consolidation of this methodology, it was considered that these groups would require specific training to break a cycle of prevailing inequality, which generates a 'shortage' of cultural capital necessary to take entrance exams for admission to Brazilian public universities.

In this context, the training of students from a perspective centered on these subjects began with the survey of their prior knowledge, which was considered in the personal trajectory, and represents one of the aspects of intercultural dialogue. This was emphasized by Castanho e Castanho (2001, p. 105): “[...] teaching that restricts itself to existing knowledge at a given moment, without taking into account the continuous additions that other researchers have made, runs the risk of maintaining partial ideas, outdated practices and archaic solutions”.

The training began at the Ferradura College-Prep Course with international discussions from universities participating in the Erasmus+-SCL Project. Historically, the methodological proposal of the Erasmus Plus Student-Centered Learning Project would be limited to the set of active methodologies, whose main difference is based on the inversion of a hierarchy, traditionally taught and practiced in universities, by considering the student as the center of the learning process. Marked by the set of pedagogical thinking from the beginning of the 20th century, especially from John Dewey (published in Brazil in 1959 and 1979), they began to be revived, a century later, in the form of “reverse planning” – backward design as in the original (Padilha, 2001; Wiggins; McTighe, 2019) or “flipped classroom” (Bergman; Sams, 2016; Valente, 2014). In this way of understanding the learning process, unlike the traditional form of educational practice consolidated in the very history of universities, the horizontalized relationships diverge from the teacher-centered role.

In order for this methodology and its principles to be properly internalized, throughout the first year of the project, training was carried out in the form of different modalities, with remote mode predominating, due to the scenario of social distancing caused by Sars-Covid-19. The formats can be characterized by the training meetings of these collaborators of the Ferradura College-Prep Course who, when playing, at the same time, the role of teachers in this project assume the centrality of the organization of the content with the production of podcasts on the concepts that underlie the Erasmus+-SCL Project. On the other hand, UNESP’s professors who teach at undergraduate programs directly or indirectly involved in the training of these students, some of whom are professors who are part of the Erasmus+-SCL Project, form the ideal locus to promote dialogue between different subjects. In this context, they dealt with topics such as planning, followed by evaluation. Initially, a sample formed by 12 teachers (undergraduate scholarship students, performing the role of teachers) and 18 students from the Ferradura College-Prep Course (graduates from public secondary education schools) was possible.

The latter, when asked about the meanings they began to attribute to student-centered learning processes in their different dimensions, from planning, implementation and evaluation (learning outcomes), stated that these methodologies, considered active, would represent an advance. It is worth noting that the questionnaires with four multiple-choice questions were sent via Google Forms to the teachers-scholarship holders (who are undergraduate students) and to students from the Ferradura College-Prep Course. Soon after, interviews with both segments took place during pedagogical follow-ups that are carried out with the different groups. The answers, whether multiple choice or essay in nature, were qualitatively analyzed in this case study by carrying out an intensive exploration of relationships between aspects of interculturality and training practices based on the SCL methodology.

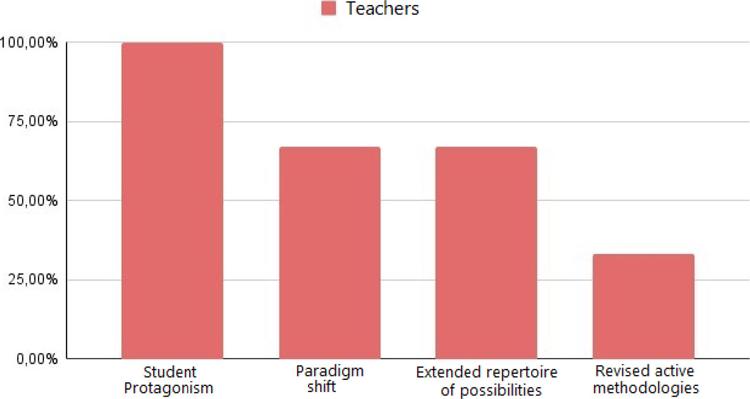

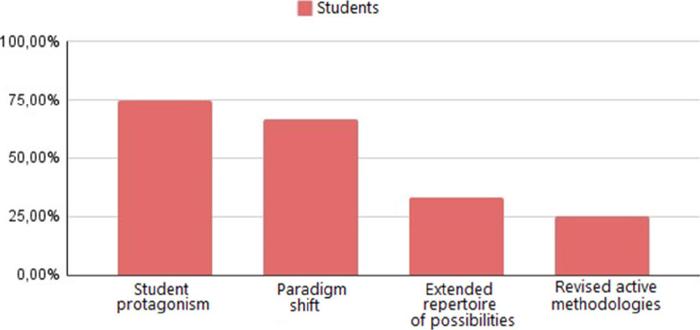

In this context, one confirms a correlational study by systematizing the results that allow inferring the construction of intercultural dialogue and the appropriation of the fundamental concepts of the Erasmus+-SCL Project. This evidence seems possible based on the answers to the two questions answered by teachers and students of the college-prep course, as shown in Graphs 1 and 2:

Source: Data gathered by the authors.

Graph 1 What the teachers came to know about the concept of SCL?

Source: Data gathered by the authors.

Graph 2 Arguments of the students for the centrality of the student in the teaching and learning process

The coincidence of the percentages obtained by these two segments regarding the ways of appropriating concepts represents one of the key aspects of interculturality: the existence of a certain synergy observed between two very distinct groups of interests: on the one hand, teachers-scholarships holders (undergraduate students exercising this function) and, on the other, students (young people and adults who graduated from the public secondary education network – the last stage of basic education). When asked about what was not known about the “student-centered learning concept” and what they came to know, the teachers/undergraduate students affirm the recognition of their condition in the role of protagonists, after all, they are undergoing training and recognize what Freire (1968b, p. 68) defined it as “no one educates anyone, no one educates oneself alone, men educate themselves among themselves, mediated by the world”. This evidence represents a paradigm shift that expands learning repertoires and revisits the so-called active methodologies, in times in which the world can be understood as the interconnected (Moran, 2000) or networked (Castells, 2000) knowledge society (Lojkine, 1995), and seems to attribute the leading role to information in itself.

Observing Graph 2, when all students stated that it was not possible for learning to occur “without being student-centered”, when choosing one of the possible options for this argument, the protagonism of this subject becomes evident, followed by the “paradigm shift”, “by the expanded repertoire of possibilities” and, last but not least, “by revisited active methodologies”. In the graphs, it can be seen that the percentages of responses from both segments – teachers and students – are similar in the selection of options sent by Google Forms, as well as in the subsequent dialogues in the interviews that dealt with the arguments for the items chosen by the respondents.

It draws attention to a possible intercultural practice, from the concepts used in these analyses, the fact that, starting from an international organization (European Union/Erasmus+-SCL Project), the foundations of this methodology represent conditions for dialogue between two segments traditionally located in opposite points: the history of the university, even with internationalization movements, is usually written by professors alone. The roles played by professors in universities are markedly hegemonic and hierarchically verticalized, making an internal dialogue in these spaces unfeasible.

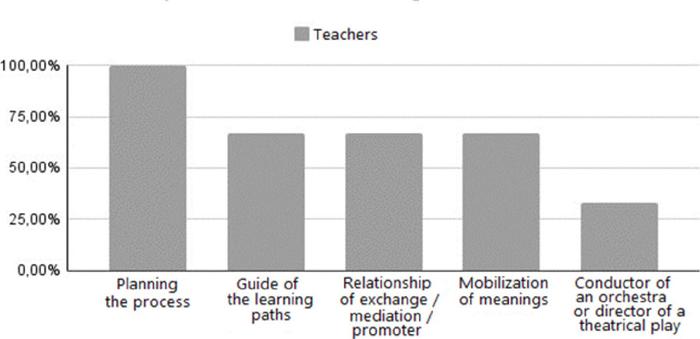

To understand this scenario, Candau (2006) considers juxtaposed practices, placed side by side, or on top of each other as multiculturality. By providing theoretical elements for a deliberate interrelationship between different subjects and socio-cultural groups of a given society, or institution, as is the case being studied, it could be characterized by aspects of an intercultural practice in education (Walsh, 2009). This inference seems to be confirmed when teachers respond about the role they would start playing if learning only occurred when centered on the student. Graph 3 allows us to observe the systematization of content expressed by teachers in planning processes, the creation of learning paths, the exchange relationship, as well as the mobilization of different meanings to achieve learning objectives. The importance of practicing planning is thus emphasized, including in a student-centered learning proposal:

Source: Data gathered by the authors.

Graph 3 According to the teachers, aspects that change in their role when one adopts student-centered learning

It should also be noted that there is a difference in roles and this does not result in inequality, inferiorization or exclusion from the teaching and learning process. Analyzed by Candau (2013, p. 98), who goes so far as to define intercultural education as “the affirmation of difference as wealth” represents one of the pillars of approaches to interculturality. The term difference, traditionally associated with a problem to be solved, now makes a relevant contribution to the occurrence of intercultural dialogue.

In the context of implementing the Erasmus+-SCL Project, having as its locus a territory of heterogeneity (and inequality, if not approached from the perspective of interculturality) as can be characterized the group of students who are part of the Ferradura College-Prep Course, it became evident the possibilities of intercultural dialogue based on an internationalization university/community outreach action. This is because the appropriations made by students and teachers, systematized in the results of the case study, denote the possibility of breaking a hierarchy in which the figure of the teacher (university professor, above all) is central and predominant. Taking into account the hegemonic cultures and traditional practices historically constructed by the university, by revisiting active methodologies and inverting the central place occupied by the teacher/professor and the student, according to Santos (2006, p. 86) we would have fulfilled the emancipatory objective of education itself – when based on intercultural dialogue – because “[...] we recovered the capacity for astonishment and indignation and integrated it into the formation of nonconformist and rebellious subjectivities”.

Final considerations

Analyzing the possibilities of intercultural practices and modes of cultural appropriation in the context of an international project involving universities from Latin American countries and led by a European university constituted the object of this research, carried out in the space of community outreach practices of a public higher education institution in Brazil. Thus, from a macro-sociological level, it was possible to revisit the possible ways of intercultural dialogues even occurring between different hemispheres – northern and southern – by constituting a team of teachers and students willing to implement a capacity building action. Starting from a structure of Erasmus Projects, the innovation of this proposal begins with the condition of effective student participation and centrality in the teaching and learning processes in the university context.

Theoretically, the text revisits concepts such as those disseminated at the beginning of the 20th century, especially with John Dewey, which resulted in the foundations of the New School in Brazil. In its time, the need to center the learning process on the student, ceasing to consider the student as someone passive, seems to reinvent the set of active methodologies. However, the historical complexity of the structuring of universities and their barely intercultural ways of implementing internationalization actions seem to have been highlighted in these analyses. By reproducing hierarchical (and successful) models that typify the institutionalization of the contemporary university itself, horizontalized and intercultural dialogues thus break with this organizational characteristic and point to possibilities for intercultural dialogue, as analyzed by Santos (2006, p. 295): “The policy of cultural homogeneity was based on large institutions, namely schools [...]”.

In the research carried out adopting the qualitative methodology of the case study, it was possible to highlight the possibilities of intercultural dialogue in higher education in two representative dimensions: internal to the institution itself (UNESP, in this case, in one of its various community outreach actions), as well as between Latin American institutions led by a European university whose objectives include seeking to expand student mobility conditions, along the lines of the Bologna Pact.

Based on a proposal from northern countries, in dialogue with some institutions from different Latin American countries, to implement a student-centered learning project, the role of planning and leading the teacher plays was reconfigured, in a multiple and diverse dialogue of distinct previously hierarchical and overlapping segments. The case studied allows us to observe that there is something innovative in these ways of building dialogues between the different (countries, institutions and social segments), which has resulted in the appropriation of concepts and practices mobilized by interculturality and the search for their implementation. Perhaps these trends are effectively having repercussions on classroom practices, when teachers and students agree on the options and arguments observed in the research, creating the characteristic synergy of this dialogue between different cultures.

Ultimately, this process seems to result from a contradictory movement: on the one hand, something recent such as the students’ new ways of learning in the unequal context of informational societies. On the other hand, student-centered learning and its potential for intercultural practices which seem to make some trends that date back to the historical condition of internationalization and dialogue with different ways of thinking of/at the university even more complex. This, in a context of willingness to reverse processes that have been naturalized, such as the daily practice of traditional classrooms and their hierarchical monologues. These analyses allow us to infer about some ongoing trends of other possibilities revisited with the complexity and depth that these times demand. Understanding these changes leads to reflection on what is innovative about this way of disseminating knowledge. The case being studied highlights a possible reinterpretation of the modes of hegemony of universities in the northern hemisphere, when they propose some type of practice in which we place ourselves as agents of transformation, through the dialogue that different cultures can foster. Thus, it seems necessary for interculturality to return to Freire (2000, p.28) for whom, “women and men, we have become more than pure devices to be trained. We have become beings of choice, of decision, of intervention in the world."

Endnote

1The other 15 universities are the Nacional de Ingeniería (Peru), Mayor de San Simon (Bolivia), Mayor de San Andrés (Bolivia), Tampere (Finland), Porto (Portugal), Deusto (Spain), Nacional Mayor de San Marcos (Peru), Libre (Colombia), Nacional de Cuyo (Argentina), Nacional de Lanús (Argentina), Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil), Nacional de Asunción (Paraguay), Iberoamericana (Paraguay), a del Cono Sur de las Américas (Paraguay) and the la Sabana (Colombia).

Nome e E-mail do translator Raniery Souza raninski@gmail.com

REFERENCES

ANDRÉ, Marli Eliza Dalmazo Afonso de. Estudo de caso em pesquisa e avaliação educacional. Brasília: Liber Livro, 2005. [ Links ]

BARBIER, Renée. A pesquisa-ação. Brasília: Plano, 2002. [ Links ]

BERGMANN, Jonathan; SAMS, Aaron. Sala de aula invertida: uma metodologia ativa de aprendizagem. Rio de Janeiro: LTC, 2016. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. O poder simbólico. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 1989. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Poder, derecho y clases sociales. Bilbao: Editorial Desclée de Brouwer, 2000. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria (org.). Educação intercultural e cotidiano escolar. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2006. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria (org.). Educação intercultural: documento de trabalho. Rio de Janeiro: GECEC-PUC-RJ, 2013. [ Links ]

CASTANHO, Sérgio; CASTANHO, Maria Eugênia de Lima e Montes. Temas e textos em metodologia do ensino superior. Campinas: Papirus, 2001. [ Links ]

CASTELLS, Manuel. A sociedade em rede. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2000. [ Links ]

CHESNAIS, François. A Mundialização do Capital. São Paulo, Xamã, 1996. [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. Como pensamos: como se relaciona o pensamento reflexivo com o processo educativo. São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1959. [ Links ]

DEWEY, John. Democracia e educação: introdução à filosofia da educação. São Paulo: Editora Nacional, 1979. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da indignação – cartas pedagógicas e outros escritos. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2000. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. 31. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2001. [ Links ]

KENSKI, Vani Moreira. Educação e tecnologias: o novo ritmo da informação. DUSSEL, Enrique. Transmodernidad e interculturalidad. (Interpretación de la filosofía de la liberación). (UAM-IZ., México). Disponível em: https://enriquedussel.com.txt/Textos_Articulos/347.2004_espa.pdf. Acesso em: 10 nov 2023. [ Links ]

LOJKINE, Jean. A revolução informacional. São Paulo: Cortez, 1995. [ Links ]

LÜDKE, Menga; ANDRÉ, Marli. Pesquisa em educação: abordagens qualitativas. São Paulo: Editora Pedagógica e Universitária, 2013. [ Links ]

MAZUR, Eric. Peer Instruction: a revolução da aprendizagem ativa. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2015. [ Links ]

MELLO, Alex Fiúza de; DIAS, Marco Antonio Rodrigues. Os reflexos de Bolonha e a América Latina: problemas e desafios. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 32, n. 115, p. 413-435, 2011. [ Links ]

MERSETH, Katherine. Cases and case methods in teacher education. In SIKULA, J. (org.). Handbook of research on teacher education. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1996. [ Links ]

MORAN, José Manuel. Novas tecnologias e mediação pedagógica. Campinas: Papirus, 2000. [ Links ]

NEGROPONTE, Nicholas. A vida digital. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1990. [ Links ]

PADILHA, Paulo Roberto. Planejamento dialógico: como construir o projeto político-pedagógico da escola. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001. [ Links ]

QUIROZ, Lopez-Hurtado. Trece claves para entender la interculturalidad en la educación latinoamericana. In: PRATS, Enric (org.). Multiculturalismo y educación para la equidad. Barcelona: Octaedro, 2007. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura Sousa. A gramática do tempo: para uma nova cultura política. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. [ Links ]

SCHAFF, Adam. A sociedade informática. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1995. [ Links ]

SIEBIGER, Ralf Hermes. Projeto ALFA/TUNING-América Latina: uma leitura a partir do cenário de sociedade e de necessidades sociais que o orientam. Revista Panorâmica, Cuiabá, v. 26, n. 2, p. 249-261, 2018. [ Links ]

SHULMAN, Lee; SHULMAN, Judith. Como e o que os professores aprendem: uma perspectiva em transformação. Cadernos Cenpec, São Paulo, v. 6, n. 1, p. 120-142, jan./ jun. 2016. [ Links ]

SHULMAN, Lee. Case methods in teacher education. New York: Teacher College Press, 1992. [ Links ]

SYKES, Gare; BIRD, Tom. Teacher education and the case idea. Review of research in education, Washington, n. 18, p. 457-521, 1992. [ Links ]

VALENTE, José Armando. A Blended Learning e as mudanças no Ensino Superior: a proposta da sala invertida. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 4, p. 79-97, 2014. [ Links ]

YIN, Roberto. Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos. Porto Alegre: Bookmam, 2001. [ Links ]

WALSH, Catherine. Interculturalidade crítica e pedagogia decolonial: in-surgir, re-existir e re-viver. In: CANDAU, Vera Maria (org.). Educação intercultural na América Latina: entre concepções, tensões e propostas. Rio de Janeiro: 7 Letras, 2009. [ Links ]

WIGGINS, Grant; McTIGHE, Jay. Planejamento para a compreensão: alinhando currículo, avaliação e ensino por meio do planejamento reverso. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2019. [ Links ]

Received: October 09, 2023; Accepted: December 05, 2023

texto em

texto em