Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de Pesquisa

versión impresa ISSN 0100-1574versión On-line ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.50 no.177 São Paulo jul./sept 2020 Epub 20-Oct-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147264

ARTICLES

RACIAL HETEROIDENTIFICATION COMMITTEES FOR ADMISSION TO FEDERAL UNIVERSITIES

IUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil; neuchaves@gmail.com

IIUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), Porto Alegre (RS), Brazil; hodofigueiredo@yahoo.com.br

The article analyzes the racial quota policy for access to higher education in a Brazilian federal university in its most recent adjustment: the implementation of a racial heteroidentification committee whose decision is based on the phenotype of the candidates. The epistemological and methodological basis starts from a critical analysis of the policy, understanding that the construction of this public action is the result of clashes and disputes between actors who have different conceptions of social justice. The result of the research points out that, in the studied university, the implementation of the heteroidentification committee has significantly reduced, since the implementation of the racial quota, in 2008, the access of self-declared black people, indicating that the commissions call into question the meaning of what it is to be a black person in Brazil.

Key words: AFFIRMATIVE ACTION; QUOTA; HIGHER EDUCATION; FEDERAL UNIVERSITY

O artigo analisa a política de cota racial para acesso à educação superior em uma universidade federal brasileira em seu mais recente ajuste: a instalação de uma comissão de heteroidentificação racial que se baseia no fenótipo dos(das) candidatos(as). A base epistemológico-metodológica parte de uma análise crítica da política, entendendo que a construção dessa ação pública é fruto de embates e disputas entre atores com diferentes concepções de justiça social. O resultado da pesquisa aponta que, na universidade estudada, a instalação da comissão de heteroidentificação retraiu significativamente, desde a implementação da cota racial, em 2008, o acesso de pessoas autodeclaradas negras, indicando que as comissões colocam em causa o significado do que é ser pessoa negra no Brasil.

Palavras-Chave: AÇÃO AFIRMATIVA; COTAS; EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR; UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL

El artículo analiza la política de cuota racial para el acceso a la educación superior en una universidad federal brasileña en su más reciente regulación: la instalación de una comisión de heteroidentificación racial que se basa en el fenotipo de los(as) candidatos(as). La base epistemológica metodológica parte de un análisis crítico de la política, entendiendo que la construcción de esa acción pública es fruto de enfrentamientos y disputas entre actores con diferentes concepciones de justicia social. El resultado de la pesquisa apunta que, en la universidad estudiada, la instalación de la comisión de heteroidentificación retraído significativamente, desde la implementación de la cuota racial, en 2008, el acceso de personas autodeclaradas negras, indicando que las comisiones colocan en causa o significado de lo que es ser persona negra en Brasil.

Palabras-clave: ACCIÓN AFIRMATIVA; CUOTAS; EDUCACIÓN SUPERIOR; UNIVERSIDAD FEDERAL

L’article analyse la politique de quotas raciaux pour accéder à l’enseignement supérieur dans une université fédérale brésilienne, d’aprèss sa dernière configuration: la mise en place d’une commission d’hétéro-identification raciale, basée sur le phénotype des candidat(e)s. L’approche épistémologique et méthodologique repose sur une analyse critique de cette politique et reconnaît que la construction de cette action publique est le fruit d’affrontements et de conflits entre acteurs aux différentes conceptions de la justice sociale. Le résultat de la recherche met en évidence que, dans l’université en question, la mise en place de la commission d’hétéro-identification a, depuis la création des quotas raciaux en 2008, considérablement réduit l’accès des personnes qui s’autodéclarent noires, ce qui montre que ces commissions remettent en question la notion d’être noir au Brésil.

Key words: ACTION POSITIVE; QUOTAS; ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR; UNIVERSITÉ FÉDÉRALE

Affirmative policies with a racial contour have given rise to several discussions and arguments - both in the academic area and in black social movements - about the meaning of race and racial discrimination in a society made up by miscegenation, such as Brazil. Historically, the Brazilian national state, as a form of social organization of modernity, has produced and reproduced a legal institutional framework that has resulted in the exclusion of the black population from access to social, economic and cultural goods. This institutional racism has acted in a diffuse way in the day-to-day operation of institutions and organizations, causing inequalities, from the racial standpoint, in the distribution of services, benefits and opportunities to the different segments of the population (LÓPEZ, 2012). This assertion can be attested by social indicators, produced by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), which, recurrently, demonstrate that black and brown people are the ones who suffer the most from the most diverse forms of violence, from formal unemployment - which causes high rates of informal occupations, with lower salaries when compared to white people -, from low schooling caused by early school dropout, lack of professional qualification, in short, structural poverty (IBGE, 2019).

The materiality of this reality has generated its opposition, reflected by the organization of the black social movement, which, in this first quartile of the 21st century, fights for public policies that can lead to a process of institutional de-racialization, with impacts on the Brazilian society as a whole. On the other hand, academic research in the area of human sciences have centered efforts to unveil the mode of operation of social exclusion mechanisms affecting black people in Brazil (NEVES, 2018; GOMES, 2012; DOMINGUES, 2007; GUIMARÃES, 2004; CARVALHO, 2003).

This article aims to address the affirmative policy of racial contour for higher education admission at public federal universities, examining the case of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). The UFRGS affirmative action program of social quotas was implemented in 2008, with 30% of admissions in all undergraduate programs reserved for students coming from public schools. Of this percentage, a quota (15%) was reserved for students coming from public schools who self-declared black people (black or brown). In 2012, the Federal Quotas Law (BRASIL, 2012), the reservation of admission vacancies for people coming from public schools at the federal public higher education institutions reaches 50%. At UFRGS, the reservation of admission vacancies for students self-declared black, brown or indigenous people coming from public schools is of 25%, considering the 50% reservation.

In this context, we propose a critical analysis of UFRGS’ affirmative policy, considering its most recent adjustment, that is, the implementation of a heteroidentification committee, in 2018, to verify self-declared black (black or brown) candidates. The committee checks the racial self-declaration having the candidate’s phenotype as the central reference. Considering that this process has not happened without confrontations and disputes between the different actors involved in the production of meanings to the affirmative policy of racial contour at UFRGS and in Brazil, we base our study on the following question: what are the first effects/results of the implementation of the heteroidentification committee on the admission of black people to undergraduate programs at UFRGS?

In order to provide epistemological and methodological support to the arguments of this research, we understand the study of affirmative policies for access of black people to federal public universities as a cycle of policies that incorporate interrelated contexts of influence, of text production, and of practice (BOWE; BALL; GOLD, 1992; BALL, 1994; MAINARDES, 2018).

In the context of practice, the policy can be interpreted and recreated by the actors who are directly involved in the social demand; in this context, which presents clashes and disputes for the policy recontextualization and re-creation, results or social justice effects are usually produced. The actors involved in the context of practice (in the case of UFRGS, students, macrostructure managers, black movement, professors, technical and administrative staff etc.) are not mere implementers of affirmative policies in the institutional level. In this case, they act1 on the policy in such a way that the product of this action process constitutes something different from what was originally written in the affirmative policy text, making it a social and local construct; however, it is recognized that the action is discursively produced in part, that is, that the possibilities of thinking and talking about affirmative policies are articulated and disputed within the limits of certain discursive possibilities (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016; MAINARDES, 2018) that incorporate power relations based on institutionalized hierarchies (BOURDIEU, 1996).

For the interpretation of the injustices caused by racism and racial discrimination, we adopted the concept of social justice by Nancy Fraser (2006; 2008), which presents a three-dimensional approach: socioeconomic, cultural and political. In the first dimension, the struggle for justice takes place within the scope of the fair redistribution of economic resources aiming at the transformation of the basic economic structures of class exploitation, it concerns the social class. In the second dimension, the struggle is for the recognition of equal status for all people interacting in the social space, with a view to a cultural or symbolic change, it concerns cultural identities. The third dimension offers the stage, the public sphere, on which the struggles for redistribution and recognition materialize through the equal participation of right-holders in the production of meanings for public policies. We believe that racism and racial discrimination produce injustices in the three dimensions mentioned; for this reason, the struggle of the black population is for three-dimensional social justice.

In view of the references presented as a theoretical-methodological basis, we used sources/data for the critical analysis of the question raised about the access of black people to federal universities, in view of the implementation of heteroidentification committees: policy documents, legislation, IBGE data, data produced by the Affirmative Action Coordination (CAF) and by the UFRGS heteroidentification committee, among others.

The article presents this first introductory section, in order to bring, in the second section, a perspective that reveals our conception of the idea of race and racial discrimination in the context of Western modernity. In the third section, we expose the specificity of racism and racial discrimination in Brazil in order to contextually base the racial quota policy, highlighting the protagonist action of the black social movement. In the fourth section, we undertake a critical analysis of UFRGS’ affirmative policy, considering its most recent adjustment: the implementation of a heteroidentification committee whose action is based on the phenotype of self-declared black (black or brown) candidates. Lastly, in the final remarks, we return to the central question of the article, subjecting it to interpretations of conclusive nature, always considering our epistemological choices.

RACE AND RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN THE CONTEXT OF MODERNITY

We started this section by arguing, based on the ideas of Quijano (2014), that America was the first space-time of a new pattern of a global vocation power, being, for this reason, the first identity of modernity constituted as a result of the historical processes of colonial capitalism. The new pattern of power and domination consisted of two fundamental axes: on the one hand, the codification of differences between exploiters and exploited2 in the idea of race based on a supposed difference in biological structure, which placed the exploited in a natural state of inferiority and submission in relation to the exploiters; on the other hand, the exploiters articulated all the historical forms of control of labor, resources and goods produced by the exploited around the capital and the construction of a world market.

Regarding the first axis, the formation of social relations based on the idea of race has produced social identities that are historically new in America: indigenous, black, mixed race and others have been redefined. Thus, terms such as Spanish and Portuguese and, later, European, which until then indicated only the geographical origin or one’s home country, also demanded, in reference to the new identities, a racial connotation. As social relations came to be configured in relations of domination, such identities started being associated with corresponding hierarchies, places and roles and, consequently, with the prevailing pattern of domination. In other words, race and racial identity were established as instruments of basic social classification of the population in the Americas. “En América la idea de raza fue un modo de otorgar legitimidad a las relaciones de dominación impuestas por la conquista” (QUIJANO, 2014, p. 779).

In the second axis, the new historical identities, produced based on the idea of race, were associated with the nature of roles and places in the new global structure of labor control. Therefore, both elements, race and social division of labor,3 were structurally associated and mutually reinforced, even though neither was necessarily dependent on each other to exist or change. Thus, under modern colonial capitalism in America (between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) a systematic racial division of labor was imposed, and it was maintained throughout the entire colonial period. Indeed, with the worldwide expansion of colonial capitalist domination of white European men, the social division of labor of racist basis was imposed as a criterion of social classification on the entire population on a global scale. As a result, a new technology of domination/exploitation, based on the relationship between race and work, was articulated in a way that it would be sustained as a naturally associated relationship. Such a social arrangement has been successful up to the present (21st century) (QUIJANO, 2014).

Thus, the idea of race and its relation to other dimensions of social life - among them, the social division of human labor - has no known history before America. It probably originated as a reference to the phenotypic differences between exploiters and exploited, however it was soon used as a reference for an allegedly differentiated biological structure between the two groups, whose supposed biological superiority of the first group, the exploiters, was based on the rational (scientific) knowledge of modern western European civilization. This scientific rationality is strongly fostered in the 1850-1930 period and supported, also, by the social sciences, as mentioned by Altman:

Tanbién las ciências sociales se desarrollan en este contexto, enpujadas por los estados - especialmente desde la segunda mitad del siglo XIX - hacia uma concepción estadocéntrica y nomotética (enfocada en reglas generales) de la realidad social. Se insertan, por lo tanto, en la construcción de una modernidad eurocentrada y colonial que estudian en sus efectos sociales y que producen en sus princípios científicos. La sociología (y las demás ciencias sociales) toma su realidad concreta como dada, universaliza la Europa (Y EEUU) del siglo XX, temprano como lo normal - y excluye a todo que no corresponde con esta realidad. (2020, p. 87)

This argument is reinforced by Araújo and Maeso (2013, p. 151), when they assert that race and racism should be analyzed “as ideas and historical-political phenomena of modernity”, that is, as a fundamental part of the constitution of Eurocentrism as a paradigm of knowledge production that characterizes the project of modernity and its universality claims from the end of the 15th century onwards, and therefore, on the formation of capitalism, nation-states, colonialism and the idea of “Europe”.

The construction of this discourse that justifies Eurocentric domination perpetuates its consequences in the networks of social meanings concerning the black population to the present day. After all, more and more we have lived more insidiously within democratic states cleaved by fascistic societies in which development indexes are accompanied by glaring indicators of social inequality, exclusion and ecological degradation (SANTOS, 2011).

This reality of the 21st century is also highlighted by Gentili (2009), when stating that the factors of inequality and injustice are strongly marked by the origin or ethnicity of the peoples, since the consequences of poverty have a special impact on the indigenous and Afro-Latin population. The author adds that the greatest probability of being excluded from the educational system or of having access to an education that is deeply degraded in its conditions of pedagogical development is being born black or indigenous in any country in Latin America or the Caribbean. Fraser (2006), on the other hand, infers on the mark of colonialism as a historical process that brings about racial discrimination with an effect on socioeconomic, cultural and political injustices. The materiality of such injustices can be seen in the current social division of labor, in wage differences and in different forms of exploitation such as racism, the devaluation of one culture at the expense of another (the dominant one) and the social construction of downgrading stereotypes of certain social groups.

In view of this scenario, our position before the idea of race places it as a social construction whose origin is marked by a relationship of domination, much earlier than by a biological relationship. In fact, in America, race is an idea applied for the first time towards indigenous people (that is, to the native peoples of the Americas) and not towards black people (peoples from the African continent). Furthermore, the idea of race appeared long before that of color in the history of the social classification of the world population. “La idea de raza es, literalmente, un invento” (QUIJANO, 2014, p. 78). It has no relation to the biological structure of the human species. Phenotypic traits are obviously in the genetic code of individuals and groups and, in this specific sense, are biological. However, they are not related to any of the biological subsystems and processes of the human organism, including, certainly, those involved with the neurological and mental subsystems and their functions (QUIJANO, 2014; ARAÚJO; MAESO, 2013; GUIMARÃES, 2004). In the domain of current democratic national states, the fight against several forms of social exclusion, such as racism and racial discrimination, far from being a phenomenon only in the societies of the Americas, has been fought on different battle grounds around the world. The confrontation of these forms of exclusion started being gradually designed, at an international level, from conferences organized by the United Nations (UN), in the 1970s, and such forms started being legally outlawed from that historical period onwards.4

It should be noted, however, that the 1970s, a period in which a crisis of production and consumption of modern capitalism begins, the UN organizes international conferences that address global issues, in which a variety of topics (such as the environment, human rights, human settlements, social development, among others) and issues of international interest are discussed. However, since the UN is an organization constituted by the global capitalist order, it is tainted with tensions and contradictions. It is important to remember that such themes are approached in order to maintain the development of international capitalism, that is, the central objective is to maintain a certain social balance, in the functionalist way (DURKHEIM, 2014), through the management of social conflicts (ESTÊVÃO, 2001) that provides the reduction, possible within the framework of capitalism, of social inequalities, in order to guarantee the current status quo; that is, the economic, cultural and political domination of Europe and the United States of America over the rest of the world.

In the 1950s and 1960s, fear of the consequences of destabilizing the status quo that legitimized the superiority of the West drove the rejection of the validity of racial theories and policies, taking shape in the critique of scientific racism - understood mainly as a critique of the political manipulation of the scientific knowledge, with Nazism being the extreme example. It was in this context that the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) issued several statements on the so-called racial issue, in order to fight racial prejudice. UNESCO’s stand in the 1950s and 1960s influenced UN conferences in the 1970s (ARAÚJO; MAESO, 2013, p. 150).

Thus, the crisis of capitalism proved that the maintenance of the idea of racial superiority was no longer convenient for the system. It becomes of interest to the central capitalist countries that a greater economic and social stabilization takes place in peripheral, said to be underdeveloped countries, or in development, especially African and Latin American countries, in order to promote the subservient integration of these peripheral countries into the global capitalist system. Moreover, new markets for the consumption of goods are still being created and expanded.

As Araújo and Maeso (2013, p. 150) indicate, the second half of the last century was the stage of a turning point in political discourses and projects throughout several European and North American contexts: “from the celebration of superiority to the acceptance of racial equality”. This change in direction was the result of anxieties facing the “erosion of racial certainties” and the usual “fear of racial revenge” that the growing power of political mobilization of anti-colonial projects posed onto Western white elites. In this context, currently, the signatory countries of the consensus reproduced in the documents originating from the aforementioned UN conferences and discussed by countries in America, Africa, Asia and Europe at the 3rd World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and related forms of intolerance5 in Durban, 2001, in South Africa, committed themselves to the implementation of strategies to face the racial discrimination established and naturalized in some societies, as it is the case of the Brazilian society.

THE RACIAL QUOTA POLICY IN BRAZIL AND THE PROTAGONIST POSITION OF THE BLACK MOVEMENT

In Brazil, the developments of international initiatives in the face of racism and racial discrimination have reinforced internal social struggles, namely, the black social movement (NEVES, 2018; GOMES, 2012; LÓPEZ, 2012; DOMINGUES, 2007). Black people collectives from different fields of activity entered the 21st century fighting for mandatory racial quotas in public universities and in selection processes for civil servant positions. They justify this political measure with a basis on the urgent need to repair the social, economic and cultural effects of discrimination on the black population. Such manifestations culminated in the creation and implementation of public actions, known as affirmative policies,6 with the purpose of promoting equality, equity and protection to social, racial and ethnic groups affected by socioeconomic, cultural, gender and other forms of social intolerance.

Indeed, considering the specificity of the Brazilian case, affirmative policies of racial contour, the racial quotas, have generated recurrent clashes and disputes, especially with regard to the identification of right-holders based on racial criteria within a mixed-race society.

In the case of Brazil, the racial democracy hypothesis presented by the sociologist Gilberto Freyre in the 1930s asserted that the miscegenation among indigenous, black, and white people would contribute to the creation of a Brazilian national identity, a Brazilian soul (FREYRE, 2006). By not considering the concrete situation of social exclusion of the black population, at the time it had been free from slavery for 40 years, it ended up having the effect of masking racism and racial discrimination. Still in this sense, the miscegenation as a cultural characteristic of the Brazilian population makes the African ancestral identity opaque to black people. Carvalho affirms, in this perspective, that the Freyrian ideology implied a disempowerment of identity. Thus, we have to define “racism not by the adhesion to a belief of racial superiority, but by the sustained effect of the discourses that celebrated miscegenation and silenced the assertion of the condition of black in Brazil”7 (CARVALHO, 2003, p. 169, own translation).

Reinforcing the criticism of Freyre, Gonzalez (1984) highlights that the effect of racial discrimination masking produced an ideological discourse with the purpose of domesticating the black population. For the author, there is a process of naturalization, from colonial times to the present day, of the place that exposes the racial division of the space that should be occupied by black people. The natural place of the dominant white group consists of healthy dwellings located in the most beautiful corners of the city or countryside and duly protected by forms of policing ranging from foremen, slave catchers, to the formally established police. On the other hand, the natural place of black people is the opposite, of course: from the slave quarters to the favelas, slums, invaded areas, flooding areas, and precarious housing estates. Nowadays, the criterion has been symmetrically the same: the racial division of space. In the case of the dominated group, what can be seen are whole families huddled in cubicles whose hygiene and health conditions are the most precarious. “Along those lines it is possible to understand why prisons are a natural place of black people”8 (GONZALES, 1984, p. 232, italics by the author, own translation).

Thus, considering the sociological hypothesis of racial democracy, which, according to Souza (2012, p. 105), became an ideological foundation for the formation of Brazilian society, or, in the author’s words, “a national ideological mythology that erases differences”, it can be pointed out that, in Brazil, the racial discrimination does not originate in genotypic differences based on the ancestry of the individuals, the so-called racial prejudice of origin, common in countries like the United States. Such discrimination, on the contrary, would be based on phenotypic elements, on the objectively identifiable traits of individuals and social groups. Therefore, the existence of racial discrimination based on the person’s skin color (phenotype) can be considered racial prejudice of mark (NOGUEIRA, 2006). As the author indicates:

Racial prejudice is defined as an unfavorable, culturally conditioned disposition (or attitude) in relation to members of a population, who are considered as stigmatized, either due to their appearance, or due to all or part of the ethnic ancestry attributed to them or assumed by them. When the racial prejudice is exercised in relation to appearance, that is, when it takes as an excuse for its manifestations the physical traits of the individual, the physiognomy, the gestures, the accent, it is defined as race prejudice of mark; when the assumption that the individual is descended from a certain ethnic group is enough to suffer the consequences of prejudice, it is said to be of origin.9 (NOGUEIRA 2006, p. 6, own translation)

With this perspective, the racial quota policy, in addition to being a demand from social groups excluded in the global context of unveiling racism and racial discrimination, restores, on the one hand, the discussion about what it means to be a black person in Brazil and, on the other, it awakens, in those same individuals, the desire to assert their identity based on African ancestry, reinforcing their self-esteem as well as their social esteem. Such perception the individuals have about themselves has led them to resist racial prejudice, as well as to organize10 and fight for their citizenship rights in the sphere of public institutions.

This fact is perceptible in the struggle of black people in a social movement that becomes an important political actor when bringing the debate about racism to the public scene and inquiring about the role of public policies in their commitment to overcoming racial inequalities, imbricated, explicitly , with social inequality. This (re)action of the black social movement, especially put into practice in the first quartile of the 21st century, “resignifies and politicizes race, giving it an emancipatory and non-downgrading treatment”11 (GOMES, 2012, p. 733, own translation).

For Fraser (2008), everyone affected by a given social or institutional structure has the moral status of justice holder in relation to it. What transforms a collective of people into justice holders of the same category is not geographical proximity, but their (co)imbrication in the common structural or institutional framework, which establishes the rules of social interaction, shaping their respective possibilities of life, according to patterns of advantages and disadvantages. In this sense, the fight against racism and racial discrimination is global and local and driven by the right holders in the perspective of a radical democracy.

In other words, for the black movement, race is the determining factor in the organization of black people around a common action project (DOMINGUES, 2007). Thus, contrary to the discourses on the peaceful coexistence of the races in Brazil, the relations between them have always been marked by conflicts and tensions since the signing of the Golden Law (1888), which frees, but relegates the black population to abandonment by the State , in terms of citizen integration to the Brazilian society (SOUZA, 2012; GONÇALVES; SILVA, 2000). For this reason, it is necessary to understand the black movement beyond the classic model of social movement, as are those linked to the world of work. It is essential to recognize it as capable of mobilizing identities, ancestry and knowledge; it acts as an educator who educates the state, the society, the education itself and re-educates himself in dealing with the racial issue (GOMES; RODRIGUES, 2018).

THE RACIAL HETEROIDENTIFICATION COMMITTEE AT THE UFRGS

As we have already indicated, the context of practice is where the policy is subject to (re)interpretation and (re)creation, producing effects and consequences that may present resignifications in the original policy (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016). Actors in the context of practice do not face policy texts as naive readers or mere implementers, they come with their stories, experiences, values and purposes that are diverse and produce other texts and other discourses; therefore, policies are social and local constructs. For this reason, the interpretation of policy texts is always a matter of dispute, at the limit, for the sense of social justice that permeates the idea of a fair society.

With this in mind, even before the existence of the federal policy of quotas, the so-called Law of Quotas (BRAZIL, 2012), the UFRGS University Board (Consun), in 2007, based on the demands of the black social movement12 - along with groups of professors, administrative and educational staff, students, student movement - decided to create the Affirmative Action Program at the University. It established that 30% of the undergraduate programs’ admissions would be reserved for students coming from public schools and, of this percentage, 15% would be reserved as ethnic-racial quota (UFRGS, 2007). The Program is the result of major clashes with elite social groups that, historically, have taken the vacancies offered by federal public universities and that were against the quota policy (with representatives at Consun even) using the discourse of school merit and equal opportunities (BATISTA, 2015).

In the first five years of the affirmative policy, it was required that public school graduates had completed both elementary and secondary education in the Public Education System and the ethnic-racial profile was based on self-declaration as black or indigenous individuals. During this first period of the policy, Consun once again turned into a space of dispute for the direction that would be given to the policy. This time, the confrontation would be in the sense of a demand from the black and student movement (with the support of some groups represented in Consun) that demanded the social recognition that racism is structural and institutionalized, therefore, the racial quota should be detached from the social quota as a way to break with cultural or symbolic injustice suffered by the black population (BATISTA, 2015). Although not successful in the demand, the right holders left the mark of their standpoint in public deliberation, reinforcing social justice in its political dimension, as they intervened and disputed a fair representation in the public process of decision-making (FRASER, 2008).

Then the Consun Decision no. 268 (FEDERAL UNIVERSITY OF RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS, 2012), in view of the Law of Quotas, revokes Decision no. 134, of 2007, and reorganizes the Affirmative Action Program at UFRGS, establishing, among other rules, the requirement of completing only secondary education in the Public Education System, in addition to a longest duration of the program and its evaluation, which changes from 5 to 10 years of duration, and directs the ethnic-racial contour to self-declared black, brown and indigenous people, as well as indicating the percentage of 50% of vacancies for affirmative policy and, of this percentage, 25% for black, brown and indigenous people. Decision no. 312 (UFRGS, 2016a) modifies decision no. 268 (UFRGS, 2012), and, among other changes, includes the Unified Selection System (SiSU) as an alternative for entering undergraduate programs and the possibility of extending the program (from 2022 to 2024), in addition to the creation of four modalities (based on income) for applying for reserved vacancies. These normative procedures substantially increase quota holders’ access to federal universities, with an emphasis on admission by racial quota (BATISTA, 2018).

In the process of building the policy, demands from right holders are presented, culminating in new adjustments. While a learning about the racial quota policy, the collectives of black people inside and outside the university started to require that the managers of the academic macrostructure took a stand in the face of complaints of fraud13 in the access to the vacancies reserved for people self-declared as black. The result of this demand, at UFRGS, was Ordinance no. 9,991 (UFRGS, 2016a) which instituted the Study Committee of Self-Declaration Verification, which aimed to carry out studies on possible criteria related to the self-declaration verification processes of black, brown, and indigenous candidates for admission to undergraduate programs through the affirmative policy. Subsequently, Consun’s Decision no. 312 (UFRGS, 2016a)14 establishes the Permanent Committee for the Verification of Ethnic-Racial Self-Declaration (CPVA).

Shortly after the creation of the CPVA, the Special Committee for the Verification of Racial Self-Declaration is created (Ordinance No. 10.129, of 2017), with the objective of performing the hetero-identification of students who have already been admitted through vacancy reservation since 2008 and have been denounced by black people collectives at UFRGS (process still inconclusive). From that moment on, the CPVA (with representatives from the academic community and the black social movement) became institutionalized as the body responsible for the heteroidentification procedures of self-declared (black) candidates (heteroidentification based on phenotype and documents) and indigenous (based on documents) in the selection processes for admission to undergraduate programs at the university.

As indicated by Nunes, the verification committee is a responsibility of affirmative action management, not for what was neglected from the 2012 Law of Quotas, favoring fraud, but for the emergence of another level of social relations in which the body can be de-racialized by the phenotype considered to be devious in relation to the white virtue. Also, according to the author, “the commissions do not base their judgment on bodies, but establish a political process of welcoming and receiving forgotten bodies, banned and standardized by racism”15 (2018, p. 29, own translation).

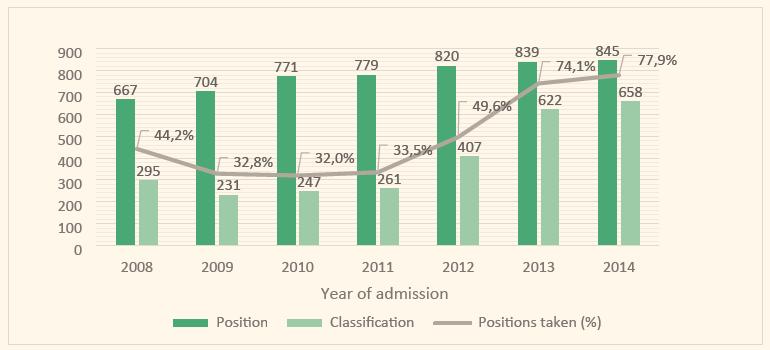

The data that follows demonstrate the offer of vacancies and the percentages of access to admissions via the affirmative policy or racial contour, considering the periods from 2008 (implementation of the affirmative policy at UFRGS) until 2018 (with the CPVA installed). From the evidence that is pointed out, it is possible to perceive the first effects of the CPVA installation with regards to the access of black (black and brown) people to undergraduate programs of the University. Graph 1 shows the classification based on the vacancies offered to black people.

Source: Relatório Anual do Programa de Ações Afirmativas UFRGS (2013, 2014).

GRAPH 1 CLASSIFICATION BASED ON THE VACANCIES OFFERED TO BLACK (BLACK AND BROWN) PEOPLE FROM 2008 TO 2014

The analysis of Graph 1 points to a low ranking between 2008 and 2012 in the vacancies destined to self-declared black people (black and brown), reaching less than 50% of the offer. In this case, the Affirmative Action Coordination (CAF/UFRGS), the body responsible for monitoring and evaluating the policy (UFRGS, 2015), identified, in 2012, the need for an equity adjustment in the policy, aiming at having the racial quota used by the right holders. The coordination asked the university’s regulatory bodies to modify the pre-classification criteria of the racial quota candidates for the evaluation of the wording, which still had classification criteria related to universal access and was eliminatory (BATISTA, 2018). With this change and with the Law of Quotas of 2012, which changes the reservation of vacancies for the affirmative policy to 50%, there was a significant increase in the classification of black people for admission to UFRGS in 2013 (74.1%) and 2014 (77.9%), as shown in Graph 1, as well as in subsequent years, which can be seen in Graph 2.

Source: Relatórios de acompanhamento interno - CAF/UFRGS (2018).

GRAPH 2 CLASSIFICATION BASED ON THE VACANCIES OFFERED TO BLACK (BLACK AND BROWN) PEOPLE FROM 2015 TO 2018

In 2015, UFRGS opted to join SiSU, which is now one of the selection processes, along with the entrance exam, for admission to undergraduate education, generating a significant increase in the number of positions offered. Graph 2 shows the significant increase in the number of students classified for vacancies for self-declared black people (black and brown) between 2015 and 2017. In 2018, in comparison, it is possible to observe a significant reduction in the number of black people admissions (436), considering the offer of openings (1,535). This discrepancy in relation to previous years is probably the result of the CPVA implementation, since it coincides with the insertion of phenotypic hetero-identification procedures as a mandatory step in the selection processes for the entrance exam and the SiSU.

This impact on the reduction of admissions of black people at UFRGS, in view of the heteroidentification based on the phenotype, in 2018, seems to be an important milestone that may come to break with the idea (ideology) that, in Brazil, miscegenation makes us all equal, in view of an alleged racial democracy. From the moment that mixed-race candidates stop competing for a vacancy of racial contour or are not assessed as black or brown by the committee, it is recognized that there is a difference between being of mixed-race and having the phenotype of a black person.

This issue is raised by the black movement at UFRGS, especially in relation to Ordinance no. 937 (UFRGS, 2018b), which, unilaterally, introduced changes in the racial verification system, now accepting resources that prove the phenotypic ancestry since the generation of the candidate’s grandparents. In March 2018, the movement16 occupied the Office of the Dean, demanding participation in the construction of the rules for heteroidentification procedures. Without a direct agreement with the Dean’s Office, they reached an agreement with the participation of the Federal Justice (Public Prosecutor’s Office). An audience term was drawn up that modified some points of Ordinance no. 937, to highlight: that the phenotypic ancestry would be accepted only as complementary to the process of racial verification, following the phenotype of the candidate as a central aspect; the participation of the black movement (collectives of black people) in the entire process of heteroidentification at the University, among others.

In terms of social justice, in the sense pointed out by Fraser (2008), the participation of the black movement in institutionalized spaces in the dispute for the meaning of what it is to be a black person, in the perspective of the struggle for the right to effective access to reserved racial spaces in the undergraduate programs at UFRGS, fulfills the notion of justice that demands that all citizens have access to resources (redistribution) and the respect they need (recognition) to be able to participate in parity with the others, as integral members of the political community.

The procedure for verifying ethnic-racial self-declaration required the UFRGS Heteroidentification Commission to be welcoming to self-declared black and indigenous people, but, at the same time, to assess the ethnic-racial veracity stated in the registration act (vestibular and SISU) by the candidates. In the process, after the verification session, the candidates received a committee opinion via the portal with the following situations: Approved (evaluated as black or brown); Not approved (not verified as black or brown); Not approved (did not appear to sign the self-declaration before the commission); Not approved (the candidate left the premises before completing participation in this administrative stage); Not approved (did not deliver the ethnic-racial self-declaration of indigenous person).17 For non-approved situations, there is the possibility of an appeal being filed by the candidate, which is analyzed by an appeal committee, which is autonomous and independent of the CPVA.

The following data, with the number of candidates summoned, absent, assessed and not assessed, reinforce our hypothesis that racial heteroidentification can be a procedure that exposes the difference between being mixed race and having the phenotype of a black person - being the latter the condition of the Brazilian citizen that causes the greatest social exclusion due to racism and racial discrimination.

The number of candidates summoned for ethnic-racial assessment by the committee, in the 2018 selection process, was 1,330. Of this total, 285 (25.2%) candidates did not attend holding a self-declared black or brown people statement, leaving a total of 1,045 (74.8%) candidates for the assessment. This piece of data already shows that there is a high abstention of candidates who are self-declared black people (black and brown), suggesting that such people rethought their blackness before appearing before the commission.

Of the total of 1,045 candidates who showed up for assessment, 357 (34.16%) were not approved as black people, and 688 (65.83%) of whom were approved. The number of approvals was significant, however we have to consider that a large part of the candidates had the information in advance that there would be verification of the ethnic-racial self-declarations by a committee, which may have inhibited the application by this access modality and strengthened the registration of effectively black people (with black or brown people phenotype).

Regarding the appeals filed by those not approved, in this calculation the appeals of the candidates who did not show up for the phenotypic verification have been included, there were a total of 451 appeals. Of this amount of appeals filed, 52 were granted by the Appeals Committee (with positive phenotypic verification for black people), which also considered photos and documents, and 399 were rejected (with negative phenotypic verification for black people or for not attending the verification session of the CPVA). Of the 740 candidates approved, 436 were admitted, in fact, as shown in Graph 2. This happens because approval by the committee does not necessarily mean aptitude for enrollment, since the candidate goes through other administrative steps, which depend on the admission option chosen at the time of registration for the entrance exam, which must be proven.

From the data pointed out, it is important to highlight, again, that the Appeals Committee is composed of people who do not belong to CPVA, which indicates, due to the proximity of the results to the number of rejected18 and deferred candidates, that the committees (CPVA and Appeals) were in tune about what it means to be a black person in Brazil. On the other hand, it can be questioned whether the high number of rejected candidates would not be causing some kind of injustice in the racial verification processes, according to the social complaint (social networks are the preferred means of reporting injustice) of blackness by a large number of candidates who were not approved. About this point, Nunes (2018) clarifies that not all candidates seek the racial quota for the purpose of defrauding, but because they are not fully aware about the unfair means by which the Brazilian racial classification is characterized. In contrast to the mode of racial democracy, the privileges acquired throughout life by belonging to a certain racial segment are neutralized.

Another issue to be highlighted concerns the candidates approved by the commissions (740) and those who did not enroll (304); that is, in 2018, 436 black people (black or brown) entered UFRGS. Here we can question the ways of disseminating information to society about affirmative policies in higher education and their admission rules. Since affirmative policies are mechanisms for the social inclusion of groups and/or social classes that did not have access to the social, cultural and economic capital of the current society, resulting in material and symbolic exclusion (BOURDIEU, 2013), it seems that the data showed that many candidates are already excluded when registering for the entrance exam or SISU, since they are eliminated in the process due to lack of knowledge about the rules that govern affirmative policies. Here there may be a need for an additional social justice adjustment.

To conclude this section, we reinforce the notion of Fraser (2008) about the equal participation of actors demanding affirmative policies in institutional instances, as a fundamental element for social justice in its political dimension (representation and equal participation), redistributive dimension (socioeconomic) and recognition dimension (cultural identities). In fact, overcoming injustice means dismantling the institutionalized obstacles that prevent some individuals from participating, under conditions of parity, with others as integral partners of social interaction in the public sphere.

We can state that, in Brazil, the fact that racism has been institutionalized, causing the exclusion of the black population from the benefits of state public policies, has created the black militancy as opposition, which is materialized, historically, by the resistance and struggles disseminated in the public sphere, demanding government actions capable of provoking a process of institutional and social de-racialization (LÓPEZ, 2012). The affirmative policy for access of black people to federal universities is an effect of such an achievement. Therefore, in this case, in terms of redistribution, understanding that admission into federal public universities increases the possibility of access to employment and higher income, the black movement destabilizes the previously instituted scenario that prevented the full participation of right holders through economic structures, which, in capitalist societies, deny the necessary resources for everyone to interact with others as peers. Regarding recognition of the order of symbolic and cultural relations, the struggle of the black movement is part of the resistance to institutionalized hierarchies of cultural valuation that have denied them the equality of status, necessary to interact with parity in the demands for rights in the Brazilian society (FRASER, 2008).

FINAL REMARKS

To conclude our argument, based on the data analyzed, we can resume the central question of this article, which aimed to investigate the initial effects of the implementation of heteroidentification committees for the access of black people to federal public universities. In the study, we showed the implementation of such committees as an adjustment of social justice, demanded by the right holders in the trajectory of the affirmative policy of racial contour itself.

In the question challenged, we indicated that the initial effects of the implementation of heteroidentification committees at UFRGS unveiled that in the current context of racial quota policy, there is a dispute about what it means to be a black person in Brazil, a mixed-race country. In this sense, the implementation of the heteroidentification committee itself is an effect of such dispute, which tends to indicate the phenotype as revealing of what it means to be a black person in the Brazilian society and, therefore, this is the social and cultural group that, historically, has suffered injustices with racism and racial discrimination. In addition, the data showed that, after the phenotype heteroidentification, the access of black people decreased significantly at UFRGS. It results that, probably, the racial self-declarations prior to heteroidentification did not correspond to the meaning of what it is to be a black person in the understanding of the right holders. The commissions also frustrate candidate fraud, especially at the UFRGS programs that more populated by social elites.

In conceptual terms, we highlighted that the idea of race (and racism) is inscribed in the early European colonizing processes in America, having been associated with possible biological differences between whites and blacks, as well as with the peoples of the Americas, supposedly based on science, with the intention of social, economic and cultural domination. Therefore, the idea of race is a social construction that needs to be understood as a historical-political phenomenon that was a fundamental part of the societal project of modernity, which conceived the universality through the formation of capitalism, nation-states, colonialism and the idea of “Europa” (ARAÚJO; MAESO, 2013). Furthermore, we reinforce the notion that the idea of race has no relation to the biological structure of the human species. Phenotype traits are biological, since they are directly related to the genetic code of individuals and/or groups. However, they are not related to any of the subsystems and biological processes of the human organism, including those that concern neurological and mental subsystems and their functions (QUIJANO, 2014). We understand that even though there are no races in the biological sense of the term, in Brazil, due to the turn towards the cultural aspect of the Freyrian racial democracy ideology, the social representation of difference is phenotypically racialized (CARVALHO, 2003).

To address the injustices caused by racism and racial discrimination, in Brazil and in the globalized world, we were guided by concepts of social justice (FRASER, 2006, 2008) that could incorporate the economic, cultural and political dimensions of social inequalities. Thus, we understand that, in modern capitalist societies, the class structure (which corresponds to the redistributive dimension of justice) and the status order (which corresponds to the cultural dimension of justice) are political categories by nature, since they are contested and permeated by power; often being treated as demands that require decision making by the State. Therefore, the political is the third dimension of social justice, constituting the space in which the struggles for redistribution and recognition are conducted through the equal participation of those right holders who reject the current idea that the national States or the transnational elites should be the entities that frame the who and how of social justice.

Finally, we highlight our ontological effort to demonstrate historical aspects of the social construction of the idea of race as a factor of discrimination and downgrading of the population of black people in America, but especially in Brazil. The affirmative policy with a racial contour, now consolidated in all federal universities in Brazil, is fully justified in the face of a social context that, backed by the values of modernity marked by Eurocentric identity models, has relegated black people worldwide the role of racial subordination.

REFERENCES

ALTMANN, P. ¿Descolonizar la sociología? Reflexiones a partir de una experiencia práctica. Foro de Educación, Salamanca, v. 18, n. 1, p. 85-101, 2020. [ Links ]

ALVES, J. A. L. A Conferência de Durban contra o racismo e a responsabilidade de todos. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política, Brasília, v. 45, n. 2, p. 198-223, 2002. [ Links ]

ARAÚJO, M.; MAESO, S. R. A presença ausente do racial: discursos políticos e pedagógicos sobre História, “Portugal” e (pós-)colonialismo. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 47, p. 145-171, 2013. [ Links ]

BATISTA, N. C. Políticas públicas de ações afirmativas para a educação superior: o Conselho Universitário como arena de disputas. Ensaio: Avaliação de Políticas Educacionais, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, n. 86, p. 95-128, 2015. [ Links ]

BATISTA, N. C. Cotas para o acesso de egressos de escolas públicas na Educação Superior. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 29, n. 3, p. 41-65, 2018. [ Links ]

BALL, S. Education reform: a critical and post-structural approach. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

BALL, S.; MAGUIRE, M.; BRAUN, A. Como as escolas fazem as políticas: atuação em escolas secundárias. Ponta Grossa: Editora UEPG, 2016. [ Links ]

BOWE, R.; BALL, S.; GOLD, A. Reforming education & changing schools: case studies in policy sociology. London: Routledge, 1992. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. A economia das trocas linguísticas. São Paulo: Edusp, 1996. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. A distinção: crítica social do julgamento. Porto Alegre: Zouk, 2013. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 12.711, de 29 de agosto de 2012. Dispõe sobre o ingresso nas universidades federais e nas instituições federais de ensino técnico de nível médio e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 2012. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, J. J. Ações afirmativas para negros na pós-graduação, nas bolsas de pesquisa e nos concursos para professores universitários como resposta ao racismo acadêmico. In: SILVA, P. B. G.; SILVÉRIO, B. R. Educação e ações afirmativas: entre a injustiça simbólica e a injustiça econômica. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2003. p. 161-192. [ Links ]

DOMINGUES, P. Movimento negro brasileiro: alguns apontamentos históricos. Tempo, Niterói, v. 12, n. 23, p. 100-122, 2007. [ Links ]

DURKHEIM, E. Educação e sociologia. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2014. [ Links ]

ESTÊVÃO, C. Justiça e educação. São Paulo: Cortez, 2001. [ Links ]

FRASER, N. La justicia social en la era de la política de la identidad: redistribución, reconocimiento y participación. In: FRASER, N.; HONNETH, A. ¿Redistribución o reconocimiento? Un debate político-filosófico. Madri: Morata, 2006. p. 17-88. [ Links ]

FRASER, N. Escalas de justicia. Barcelona: Herder, 2008. [ Links ]

FREYRE, G. Casa grande e senzala: formação da família brasileira sob o regime da economia patriarcal. São Paulo: Global, 2006. [ Links ]

GENTILI, P. O direito à educação e as dinâmicas de exclusão na América Latina. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 30, n. 109, p. 1059-1079, 2009. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. Movimento negro e educação: ressignificando e politizando a raça. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 33, n. 120, p. 727-744, 2012. [ Links ]

GOMES, N.; RODRIGUES, T. C. Resistência democrática: a questão racial e a Constituição Federal de 1988. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 39, n. 145, p. 928-945, 2018. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, L. A. O.; SILVA, P. B. G. Movimento negro e educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 15, p. 134-158, 2000. [ Links ]

GONZALES, L. Racismo e sexismo na cultura brasileira. Revista Ciências Sociais, São Paulo, p. 223-244, 1984. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, A. S. A. Preconceito de cor e racismo no Brasil. Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, n. 1, p. 9-43, 2004. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA - IBGE. Síntese de indicadores sociais: uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Brasília, DF: IBGE, 2019. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ, L. C. O conceito de racismo institucional: aplicações no campo da saúde. Interface: Comunicação, Saúde e Educação, Botucatu, v. 16, n. 40, p. 121-134, jan./mar. 2012. [ Links ]

MAINARDES, J. A abordagem do ciclo de políticas: explorando alguns desafios da sua utilização no campo da política educacional. Jornal de Políticas Educacionais, Curitiba, v. 12, n. 16, p. 1-19, 2018. [ Links ]

NEVES, P. S. C. Reconhecimento ou redistribuição: o que o debate entre Honneth e Fraser diz das lutas sociais e vice--versa. Política & Sociedade, Florianópolis, v. 17, n. 40, p. 234-257, 2018. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, O. Preconceito racial de marca e preconceito racial de origem: sugestão de um quadro de referência para a interpretação do material sobre relações raciais no Brasil. Tempo Social, São Paulo, v. 19, n. 1, p. 287-308, 2006. [ Links ]

NUNES, G. H. L. Autodeclarações e comissões: responsabilidade procedimental dos/das gestores/as de ações afirmativas. In: DIAS, G. R. M.; TAVARES JUNIOR, P. R. F. Heteroidentificação e cotas raciais: dúvidas, metodologias e procedimentos. Canoas: IFRS, 2018. [ Links ]

QUIJANO, A. Cuestiones y horizontes: de la dependencia histórico-estrutural a la colonialidad/descolonialidad del poder. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, 2014. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. S. Para uma revolução democrática da justiça. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

SOUZA, J. A construção social da subcidadania: para uma sociologia política da modernidade periférica. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2012. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Decisão n. 134, de 29 de junho de 2007 (Consun). Institui o Programa de Ações Afirmativas, através de ingresso por reserva de vagas para acesso a todos os cursos de graduação e cursos técnicos da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, 2007. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Decisão n. 268, de 3 de agosto de 2012 (Consun). Altera a Decisão n. 134/2012. Porto Alegre, 2012. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Relatório Anual do Programa de Ações Afirmativas - 2013/2014. Coordenadoria de Acompanhamento da Política de Ações Afirmativas (CAF). Porto Alegre, 2015. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Decisão n. 312, de 30 de setembro de 2016 (Consun). Altera a Decisão n. 268/2012. Porto Alegre, 2016a. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Portaria n. 9.991, de 16 de dezembro de 2016. Designa a Comissão de Estudos da Verificação de Autodeclarações de Candidatos Pretos, Pardos e Indígenas aos processos seletivos para ingresso de graduação da UFRGS por meio do Programa de Ações Afirmativas. Porto Alegre, 2016b. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Portaria n. 10.129/201. Cria a Comissão Especial de Verificação da Autodeclaração Racial para realizar a heteroidentificação de estudantes denunciados por fraude no sistema de ingresso por reserva de vaga. Porto Alegre, 2017. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Portaria n. 799, de 29 de janeiro de 2018. Cria Comissão Permanente de Verificação de Autodeclaração Racial para candidatos de processos seletivos para graduação. Porto Alegre, 2018a. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Portaria n. 937, de 31 de janeiro de 2018. Orienta sobre a interposição de recursos contra o resultado de verificação fenotípica quando do ingresso em curso de graduação desta Universidade. Porto Alegre, 2018b. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL - UFRGS. Relatório de Acompanhamento Interno - 2018. Coordenadoria de Acompanhamento da Política de Ações Afirmativas (CAF). Porto Alegre, 2018c. [ Links ]

1For further information on the “action in policies” theory, instead of implementation, see (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016).

2In the original text, the author uses the terms conquerors and conquered. We adapted the Portuguese term using exploiters and exploited, as we understand that the meaning of this translation more adequately expresses the exploitation processes of Latin America in the period of colonial capitalism.

3For further clarification on the specificity of this organization of labor in the colonies of the Americas, based on the race of the worker, see Quijano (2014).

4Except for legalized racial segregation - Apartheid - in South Africa, which lasted 46 years, starting in 1948, officially ending in 1994.

6Reservation of vacancies in selection processes for civil servant positions, in public higher education and technological institutions for black people (black and brown) and people with disabilities (PWD).

7 In the original: “racismo não pela adesão a um credo de superioridade racial, mas pelo efeito continuado dos discursos que celebraram a mestiçagem e silenciaram a afirmação da condição de negro no Brasil”.

9 In the original: “Considera-se como preconceito racial uma disposição (ou atitude) desfavorável, culturalmente condicionada, em relação aos membros de uma população, aos quais se têm como estigmatizados, seja devido à aparência, seja devido a toda ou parte da ascendência étnica que se lhes atribui ou reconhece. Quando o preconceito de raça se exerce em relação à aparência, isto é, quando toma por pretexto para as suas manifestações os traços físicos do indivíduo, a fisionomia, os gestos, o sotaque, diz-se que é de marca; quando basta a suposição de que o indivíduo descende de certo grupo étnico para que sofra as consequências do preconceito, diz-se que é de origem.”

10For example, the creation of the Unified Black Movement (1978); the creation of the Palmares Foundation (1988); the Zumbi dos Palmares march (1995); the creation of the Interministerial Working Group for the Black Population (1995), the result of the speech proffered by President Fernando Henrique Cardoso recognizing the existence of racism in Brazil (NEVES, 2018).

11In the original: “ressignifica e politiza a raça, dando-lhe um trato emancipatório e não inferiorizante”.

12At UFRGS, the black social movement is made up of collectives of black people who identify with the agenda of the social movement, however, each has its specificity. Collective groups: NegraAção, Negro das Exatas, Dandara, Afronta, Balanta, Muralha Rubro Negra, Coletivo de Educação Akualtune and Coletivo Corpo Negra.

13UFRGS; Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPEL); Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV); Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG); Universidade de Brasília (UnB); Universidade Federal do Espirito Santo (UFES); Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), among others.

14This decision also modifies Decision no. 268 (UFRGS, 2012), and allocates part of the percentage of the reservation of vacancies for students coming from public schools (50%) to people with disabilities (PWD).

15In the original: “As comissões não fazem um julgamento de corpos, mas instauram um processo político de acolhimento e recepção aos corpos esquecidos, interditados e normatizados pelo racismo”.

16This social movement gathers the collective groups of black people at UFRGS. It occupied the Office of the Dean at UFRGS for eight days, being identified as Ocupação Akilombada.

17There was only one candidate self-declared as indigenous who was not approved because he did not present the necessary documentation for the effective recognition of his belonging to the indigenous community.

18It is important to note that the Appeals Commission, according to the rules published in the public notice (entrance exam and SiSU - 2018) for admission by affirmative action, did not recognize the appeals filed by the candidates who did not attend the CPVA verification session, all were dismissed.

Received: April 01, 2020; Accepted: May 13, 2020

texto en

texto en