Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Cadernos de Pesquisa

Print version ISSN 0100-1574On-line version ISSN 1980-5314

Cad. Pesqui. vol.53 São Paulo 2023 Epub Sep 13, 2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/198053149898

TEACHER EDUCATION AND TEACHING

TEACHER EDUCATION: A NEW RATIONALITY VIA UNIVERSITY OUTREACH

IUniversidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB), Senhor do Bonfim (BA), Brazil; souzacastrom@gmail.com

IIUniversidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB), Camaçari (BA), Brazil; silvarfribeiro@gmail.com

This article aims to correlate outreach principles and guidelines with policies on teacher education and on action in the public school. To that end, the study considered Resolution n. 2/2015, Resolution n. 2/2019 and the Base Nacional Comum Curricular [National Common Curriculum Base] (BNCC). The qualitative approach was carried out using thematic analysis with the software MAXQDA to extract possible correlations between education and action policies. The theoretical framework on education for autonomy and social commitment informed the analysis perspective, considering university outreach as an educational-scientific-social field which enables a critical- emancipatory teacher education. Results indicate that outreach is the reference locus for providing creative responses to education policies.

Key words: UNIVERSITY OUTREACH; EDUCATION POLICY; COMPLEX THINKING; RATIONALITY

Este artigo objetiva correlacionar os princípios e as diretrizes da extensão com as políticas de formação de professores e de ação na escola pública. Para isso foram consideradas a Resolução n. 2/2015, a Resolução n. 2/2019 e a Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC). A abordagem qualitativa foi realizada com análise categorial temática pelo software MAXQDA para extrair possíveis correlações entre as políticas de formação e ação. O aporte teórico de formação para autonomia e compromisso social subsidiou a ótica de análise, considerando a extensão universitária como campo educativo-formativo-científico-social que possibilita uma formação docente crítico- -emancipadora. Os resultados indicam que a extensão é o locus de referência para dar respostas criativas às políticas educacionais.

Palavras-Chave: EXTENSÃO UNIVERSITÁRIA; POLÍTICA DA EDUCAÇÃO; PENSAMENTO COMPLEXO; RACIONALIDADE

Este artículo tiene como objetivo correlacionar los principios y las directrices de la extensión con las políticas de formación de profesores y de acción en la escuela pública. Para eso fueron consideradas la Resolución n. 2/2015, la Resolución n. 2/2019 y la Base Nacional Comum Curricular [Base Nacional Común Curricular] (BNCC). El abordaje cualitativo fue realizado con análisis categórico temático utilizando el software MAXQDA para extraer posibles correlaciones entre las políticas de formación y acción. El aporte teórico de la formación para la autonomía y el compromiso social subsidió la perspectiva de análisis, considerando la extensión universitaria como un campo educativo-formativo-científico-social que posibilita una formación docente crítico-emancipadora. Los resultados indican que la extensión es el locus de referencia para dar respuestas creativas a las políticas educativas.

Palabras-clave: EXTENSIÓN UNIVERSITARIA; POLÍTICA EDUCATIVA; PENSAMIENTO COMPLEJO; RACIONALIDAD

Cet article vise à relier les principes et les lignes directrices de l’extension universitaire avec les politiques de formation des enseignants et d’action publique dans le domaine éducatif. Pour ce faire, la Résolution n. 2/2015, la Résolution n. 2/2019 et la Base Nacional Comum Curricular [Base nationale commune curriculaire] (BNCC) ont été prises en compte. Dans le cadre de cette recherche d’approche qualitative, une analyse catégorielle thématique a été réalisée par le logiciel MAXQDA, afin d’extraire de possibles corrélations entre les politiques de formation et d’action. L’apport théorique sur la formation à l’autonomie critique et à l’engagement social a étayé la perspective de l’analyse, en considérant l’extension universitaire comme un champ aussi bien éducatif et formatif que scientifique et social qui permet une formation enseignante à la fois critique et émancipatrice. Les résultats indiquent que l’extension est le locus de référence pour donner des réponses créatives aux politiques éducatives.

Key words: EXTENSION UNIVERSITAIRE; POLITIQUE ÉDUCATIVE; PENSÉE COMPLEXE; RATIONALITÉ

In this article,1 we seek a pathway to give creative responses to policies on teacher education and action for basic education. As Ball (2011, p. 46, own translation) points out, a response to a policy must be “built in context, counterposed or balanced by other expectations, which involves some type of creative social action”. We assume that the locus for this creative exercise lies in the introduction of university outreach into curriculums, in the context of teacher education and of action in the school. For this reason, we present the “breaches/detours” found in the normative documents on teacher education and action in order to inform/support the model of new rationality for university outreach, specifically in the area of sciences and mathematics teacher education.

The concepts of “open rationality” and “breaches/detours” used by Morin (2015a, 2015b) inform the theoretical construction and direct the focus to the normative documents concerning teacher education: Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Teacher Education), Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Continuada de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Continuing Education), and Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Continuada de Professores da Educação Básica (BNCC-TCT). We chose these documents because we are interested in breaking with the disconnection between curriculum policies for teacher education and the arena of action in educational and social practice. To highlight that it is necessary to give a social orientation to the binomial teacher education and action, we correlated these documents with the concept of university outreach that is present in the Política Nacional de Extensão Universitária [National Policy on University Outreach] (PNExt) and in the resolution that defines the guidelines on outreach (Resolução [Resolution] n. 7, 2018). We also build on the conceptualizations of outreach advocated by Gatti (2019) and Machado (2019) and on the comprehension of teacher education as a critical and emancipatory consciousness-raising process, as advocated by Freire (2019a).

To build this correlation, we initially highlight the historicity of the movements, actions and orientations that culminated with the institutionalization of outreach, the focus of this text. Then we expand the discussion based on the comprehension that, by using as a parameter the concept and conceptualizations of university outreach as an “educational, political and social principle” (Fórum de Pró-Reitores de Extensão das Instituições Públicas de Educação Superior Brasileiras [Forproex], 2012), as a space where it is possible to transcend “half-education” (Adorno, 1995) models and as a path to diversity and interculturality (Nogueira, 2019), it is possible to build a model for university outreach actions with a view to an emancipatory education (Santos, 2011) and to an education for autonomy and social commitment (Freire, 2019b).

The PNExt legitimizes the constitutional principle of inseparability and the concept of this function, as well as its guidelines and fields of action. The Resolução n. 7, de 18 de dezembro de 2018, in connection with the PNEU and the Plano Nacional de Educação [National Education Plan] (PNE), Lei [Law] n. 13.005 (2014), consolidates and expands the concept, the inseparable principle and the guidelines on university outreach. In turn, the educational policies are directed to teacher education policies and practices and are related to a few principles that can be economic and political as well as economic-political-social in nature. They always contain references to previous policies, point out legal and institutional needs, “beliefs and values (convergent and sometimes divergent), pragmatic stances, creativity, experimentations, stabilization, gaps and spaces, dissensus and material and contextual constraints” (Ball & Mainardes, 2011, p. 13, own translation).

The educational policies are legitimized both by institutional discourses (guidelines, resolutions, political-pedagogical projects, the plans and projects developed in contexts of action-school, etc.) and by personal discourses (the subjects participating in the process). In sum, they can be considered as a set of techniques, categories, objects and subjectivities (Ball, 2011). Whatever the field of analysis, they should not be seen distant from the relationship between the structural and conjunctural spheres (Frigotto & Ciavatta, 2011), i.e., they cannot be seen in detachment from the political field, the academic field or the subjectivities that they build.

In order to look at the “details”, while keeping a macro perspective, we add lenses to one of the university policies - that on university outreach - vis-à-vis the national policies on teacher education (BNC-Teacher Education) and the guiding/normative documents on pedagogical approaches and actions for basic education (BNCC and BNCC-TCT). We consider that this is necessary because the themes responsibility, justice and transformation are at the genesis of university outreach and have always constituted the main challenge for university institutions.

In order to establish correlations between the documentary sources, showing similarities and/or dissimilarities between policies, it is assumed that university outreach policy brings subjects undergoing teacher education closer to the social agenda, and that the foundations of teacher education policy are usually closer to technical standards, i.e., know-how.

Thus, we highlight in the texts of the analyzed objects the concept of a theoretical-practical-humanistic education using a specific set of codes that allows us to see, with mathematical language - similarity matrices and graphs -, the similarities and dissimilarities as “breaches/detours” that can be used in a critical and creative manner to develop university outreach actions to their full potential, i.e., with an educational, political and social dimension and, possibly, in the introduction of this function into curriculums.

Regarding the similarities, there are findings of a pedagogical and of a professional nature. As for the dissimilarities, we found a teacher education ideal that is far from social, political-educational and scientific presuppositions. These findings lead us to reflect about what our role is in the face of the separations found.

Ball (2011, p. 46, own translation) ponders about the questions that must be asked in relation to policies. It is necessary, according to the author, to understand that “policies do not say what to do; they create circumstances where the range of options available about what to do are established”. For the author, in addition to exposing policies’ contradictions and paradoxes, there must be some kind of “creative social action”. That is what we intend to build in this work.

The analyses conducted by different authors indicate that the alignment of public policies in Brazil is built from a neoliberal guidebook, based on economistic approaches centered on productivity and alignment with market demands (Candau, 1999; Silva, 2020; Lima & Sena, 2020; Costa et al., 2021).

The foundations of these policies are set around competencies, a model built on “ideas” from the World Bank and foundations and business groups which define the competencies and skills to be developed by education. Antunes (2018) denominates this model a “privilege of servitude”, in which there is a stimulus by the private sector to, and an imposition on the working class of, a specific standard, which is to have competencies to be in line with work demands.

For Lima and Sena (2020), the foundations of BNCC characterize a regression to an overly technical worldview in which teaching revolves around competencies - know-how. Bazzo and Scheibe (2020) point out that the agenda of maintenance of capitalism directs discussions and debates about basic education teachers’ education and that BNCC is far from an education that develops students’ autonomy and critical spirit.

About BNC-Teacher Education, Nogueira and Borges (2021) point out associations’ main criticism of the resolution:

. . . the disregard for instituted policies and for Brazilian output and innovative thinking in education that goes beyond the pedagogy of competencies; the distortion of education cores; the pedagogical education and the second license violate the pedagogical autonomy of teacher education institutions and their relationship with basic education, they relativize the importance of supervised internships. (Nogueira & Borges, 2021, p. 199, own translation).

These authors add that there is a negative impact of the new BNC-Teacher Education on continuing education due to the presuppositions underpinning initial teacher education - “the overly technical and practical nature” - and they consider that:

. . . these connections impact continuing education directly as they end up making it work as spaces of teacher preparation, making up for initial education and separating theory from practice, i.e., they make continuing education something superfluous in teacher education. (Nogueira & Borges, 2021, p. 200, own translation).

Using Castells’ (2018, p. 340, own translation) reflections about the “restructuring of the capital-work relationship”, we can infer that there is a consensus about a historical redefinition in the relationship between capital and work. According to the author, education is the locus of construction of a social morphology linked to the interests and needs of society in which “the capitalist mode of production gives form to social relationships in the entire planet” (Castells, 2018, p. 555, own translation).

A reformation of thought is in course which puts the center of teaching action - the teacher and the action context, the public school - on the central stage of a homogenizing discourse. We believe that “another rationality” for teacher education can be reached at the junction between the university and the public school, by means of university outreach.

Problematization, context and goal

The isolation of the university from social agenda, from a historical perspective, can be traced back to the time when the hypothetical universe of ideas, scientific certainty and the towers of monarchic power governed the way of directing how one saw the world. Teixeira (1964, p. 27, own translation) describes that the university possessed “a culture out of time” until the late 19th century, and that the scientific, industrial and democratic revolutions began to transform the idea of this institution.2

Salles (2020, p. 16, own translation) says that because universities are projects still recent in Brazil, particularly in some regions, they are “an unstable territory that suffers from a double deficit - one of representation and another of representativity”. The author notes that it is possible to overcome this challenge and achieve “academic excellence”, “as long as there is a deeper social commitment” (Salles, 2020, p. 16, own translation). And Santos (2011, p. 67, own translation) underscores that in order to face the challenges that were posed to this institution over the past decades, it is necessary to “reconquer legitimacy through five fields of action: access; outreach; action research; ecology of knowledge; public university and school”. We took on the challenge presented by the authors, proposing an approach that legitimizes the five proposed fields, using two pathways: outreach and public school.

In the official documents in effect in Brazil since the return of democracy, outreach is addressed with different rationalities and agendas. It is linked to students’ dynamism, as the symbol of the call for the university to fulfil its cultural, professional and social mission (Anjos, 2014). It also connects with the popular movements that invigorate the life of university outreach (Gadotti, 2017), with the struggle of the teachers’ movement about the inseparability between teaching, research and outreach, and with the continuous discussion about the university’s social commitment (Anjos, 2014). These causes are guided by the solid and constant building of the agenda for the institutionalization of university outreach by the Fórum de Pró-Reitores de Extensão das Instituições Públicas de Educação Superior Brasileiras [Forum of Associate Deans of Outreach] (Forproex).

However, it is necessary to consider that the roles of the university - teaching, research and outreach - experience dilemmas arising from its obligation to assess quality, ensure its social commitment, enhance exchange between knowledge areas, and recognize new times (Salles, 2020, p. 49). Maybe it is these dilemmas that hinder the adoption of outreach as an educational and political process.

Botomé (1996, pp. 145-186, own translation), in pointing out the “mistakes of university outreach”, suggested, nearly three decades ago, that an “institutional reengineering” process is necessary, one that involves the idea of a “multidisciplinary organization of the university’s sectors, of understanding the role of the knowledge that the university produces and commands” and “of enhancing its action through praxis (alternating action and reflection)”. To operationalize this, it may be is necessary to rethink the presuppositions which underpin the curriculum organization, associated with the forms of integrating individuals into actions.

Taking the idea above as central, we delimit as the general goal of this article to correlate the principles and guidelines of outreach with the policies on teacher education and on action in the school.

Theoretical foundations

In order to build a model that enables a new/another open rationality for the object researched, we initially present Morin’s (2015a, 2015b) concept of “open rationality” and “breaches/detours”. We also use Santos’ (2013) and Freire’s (2019b) concept of education for autonomy and social commitment, so as to subsequently search for creative answers to policy, as suggested by Ball (2011).

In the epistemology of complexity, what characterizes thought is the “organizing/creator movement . . . which in a complex dialogue . . . elaborates, organizes, develops, in conception mode, a sphere of multiple speculative, practical and technical spheres . . . which expand in the sphere of language” (Morin, 2015b, p. 201, own translation). In these terms, we can say that the actions developed in contexts of teacher education and action result from processes of analysis (part) - synthesis (whole) - explanation - comprehension. In this movement, thought, language and action interact and self-organize to deal with the phenomena that pervade subjects’ activities. In the present case, it is necessary to consider the educational policies in the context of teacher education and action.

The development of educational policies is seen by bodies which form the top hierarchy, based on the rationality that underpins education, which is that of functionality and effectiveness. Therefore, it is far from the human context and dimension which form this fabric. However, there is a reality that must be considered which is fundamentally complex, comprising dimensions that are institutional and personal.

Morin (2015b, p. 341), in addressing the fundamental problems of the organization of work, reflects about the phenomena which appear in situations where a large number of individuals are involved. The author highlights the schema he calls pseudo-rational as it contains the idea of hierarchy - “might makes right” -, the center of command, with those who decide and those who execute, this division constituting specialization. For the author, this form of rationality leads “to a decrease in autonomy and to inhibition of competencies and potentials” (Morin, 2015b, p. 344, own translation). This inhibition can lead to submission to the hierarchy’s determinations, but the author notes that this submission is reversible3 and he uses a broader meaning for the term “hierarchy”, arguing that:

Hierarchized organization is not only the submission of the low to the high, of the specialized to the non-specialized, of execution to command, but also the development and flourishing of emergences from below, from one level to another . . . is not restricted to the submission of beings, it is also the production of beings and individualities ever richer. (Morin, 2015, p. 350, own translation).

We situate this hierarchy-emergence movement as a way of leaving the rationality that contains directive, supposedly effective activities and going to the extreme. Therein is “the complex rationality in which antagonisms, concurrence, disorder and diversity can be taken as a source of evolution and development of complexity” (Morin, 2015b, p. 453, own translation).

Thus, what was supposed to be seen through a directive logic of combating disorder, concurrence and instability comes to be seen as a field of complementation and co-organization that is vital to development and evolution. And “the apparent irrationality becomes the open rationality of a system which must permanently face the forces of destruction and death”4 (Morin, 2015b, p. 456, own translation). Therefore, conceiving an open rationality regarding this object of study is looking at the systems of ideas - hierarchically presented in a logic of specialization, effectiveness and efficiency - not only from the living reality that composes it (the people, the context and the institutionalities) but also from the perspective of confrontation, which enables the emergence of other angles and other actions to be performed.

We affirm that the dialogic relationship between rationality - a thought which devises conceptions and the critical capacity which disintegrates ideas closed into a single conception - and creative imagination - which confronts and discusses - offers not only complete information, but most of all, possibilities of contraposing dominant thoughts and possibilities of “detours”. We adopted the term “detour” as in “breaches” opened by the awareness that closeness-separation leads to a thought about the object and the possibility of critical reflection and creative in- tervention. In these terms, we seek “creative” responses to the circumstances that were imposed by educational policies.

Methodological approach

With the central idea of pointing out similarities and/or dissimilarities in relation to the terms that conceptualize outreach and its guidelines, in coordination with the normative/normalizing documents on teacher education and action, we build on the methodological approach based on multi-referentiality.

The technique of content analysis (CA), with the help of the software MAXQDA, was used to evidence quantitative data - the frequency of words and expressions in line with the concepts of outreach (CExt) and outreach guidelines: inseparability, interdisciplinarity and interprofessional relationships - and enable the qualitative analysis of this data through a more detailed examination, which characterizes the analysis process.

We recognize that there is a complexity which is inherent to the object of this study and to the reality about which we infer, i.e., teacher education and action policies. These two poles have dimensions which can be seen as complementary because they can be considered as heterogeneous fields. In order to understand them, it is necessary to use different analysis lenses.

University outreach has implications for the curriculum and the “organization of research” (Resolução n. 7, 2018, p. 28, own translation), thus constituting an object of teaching and research that involves both the field of education and that of organization and management sciences. In turn, the field of teacher education and action policies - BNC-Teacher Education and BNCC - is a part of a whole and involves the institutional, educational, social and juridical dimensions.

The nature of these normative documents is educational and juridical, but it is also operational. Here, there is a dialectical relationship between the institutional meanings of these documents and the personal meanings given by the collective involved in the process (marked by the social and educational reality), which leads us to think about what in these documents can be highlighted in the field of teacher education and of action. This presupposes an expansion of purposes and foundations. To that end, it is necessary to establish a connection between structures and normative documents, which were thus far seen as dissociated. This movement is possible when the object starts to be seen from the perspective of interactions and relationships, hybridizations between the documents, personal and cultural values; therefore, it does not contain a sole reference.

What can emerge from a multi-reference approach to these documents is not only a condensed set of information presented with variables and distinct parameters, but rather a set of indicators that allow shedding light on other possibilities. In other words, it is necessary to evidence relations in which “another rationality” can be built for these normative/normalizing documents that support teachers’ education and action.

To avoid the risk of having a sole reference and a sole language, we adopted as techniques CA and document analysis. Bardin (2016, p. 29, own translation), in defining CA and conceptualizing it as an instrument that enables a “relationship with other sciences”, explains that, for some authors, it is defined “as a set of techniques”. Pêcheux (1987, p. 59, own translation), in pointing out the “neighborly relationship between linguistics and text analysis”, says that “content analysis and sometimes text analysis” (author’s emphasis) are analysis practices that seek to “answer questions concerning the semantic and syntactic uses shown by the text in order to point out the comprehension of the text” (Pêcheux, 1987, pp. 59-60, own translation).5 About CA, Michinel (personal communication, 2018)6 sees it as a research technique intended to formulate, based on certain data, reproductible and valid inferences which can apply to a context that requires resignification.

Given the object of this study, we sought to connect CA and document analysis. For Bardin (2016, p. 48, own translation), “the goal of document analysis is the condensed representation of information”, and that of CA is the “handling of messages (a content and the expression thereof) to show de indicators that allow inferring about another reality than that that of the message”. The author also says that document analysis is not restricted to “thematic category analysis”. For her, the semantic categorization criterion can be considered as a “classification of the elements that constitute a set by differentiation and regrouping . . . with the predefined criteria”, grouping thematic categories that might express “invisible indices” (Bardin, 2016, p. 145, own translation). Thus, an inventory was made - in which the elements were isolated given their signification for the endeavored context (that of teacher education and action) -, so as to identify breaches that might enable building a “new rationality” for teacher education and for action in the school. That said, we have an epistemological characterization in which the meaning of the analyzed corpus is exploratory and semantic, with the following analysis question: What do the documents indicate about questions that might enable the development of a critical, emancipatory teacher education by means of university outreach?

The data: Presentation and analysis

To assign a meaning to the configuration given to the object, we begin with a historical approach to university outreach, pointing out the political and institutional guidelines, the models of the proposed actions, and the signification/definition given by Anjos (2014), Gatti (2019) and Machado (2019). Then we present the data and analyze the similarities and dissimilarities found.

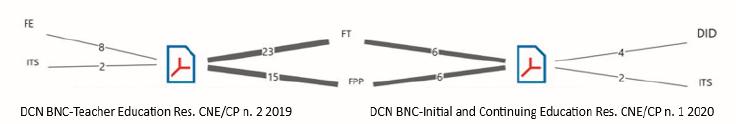

We use two approaches for this analysis. The first, from a conceptual dimension, points out possible similarities between the concept of outreach present in the PNExt and in the outreach resolution, in connection with the context of the educational policy on teacher education - diretrizes curriculares nacionais [national curriculum guidelines] (DCN): Resolução n. 2, de 1º de julho de 2015, and Resolução n. 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019 (BNC-Teacher Education), in addition to Resolução n. 1, de 27 de outubro de 2020 (BNC-Continuing Education).

The second approach indicates the correlation, using the educational policy on action, between the BNCC and BNCC-Transversal Contemporary Issues (TCT). Thus, the educational conceptions of the documents are highlighted, presenting the frequency of codes that indicate a path to expanding students’ universe of reference.

From the perspective of university outreach’s historicity

In Table 1, we present the directions that have guided this object, based on the contents of the PNExt (Forproex, 2012, pp. 18-23). For this analysis, we build on theoretical work by Anjos (2014), Gatti (2019), Machado (2019), Nogueira (2019) and Bonassina (2020), and on an interpretation of our own, founded on the comprehension of the political-educational dimension of this function.

Table 1 Outreach directions in Brazil

| Period | Directions | Outreach model | Authors’ views/analyses |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950-1960 | Organization of cultural and political movements - União Nacional dos Estudantes [National Students’ Union] (UNE) (Forproex, 2012, p. 18). | Cultural and political movements that contributed to the training of leaders required by the country (Forproex, 2012). | Propagation of the political perspective to university outreach. Conception based on transformation, humanization and emancipation, influenced by Paulo Freire (Machado, 2019). |

| 1966-1970 | Creation of the Centro Rural de Treinamento e Ação Comunitária [Rural Center for Community Training and Action] (Crutac) and the Rondon Project - subordination to the Política de Segurança Nacional [National Security Policy]. | Outreach through knowledge sharing based on experiences with rural communities. | Integration of the university into the regional context (Nogueira, 2019). |

| The university reform is enacted (Lei n. 5.540, 1968). | “Universities and higher education institutions are to extend to the community, through courses and special services, the teaching activities and the results of research inherent in them” (Lei n. 5.540, 1968, own translation, emphasis added). | Nuances in the transition from an inorganic, event-based conception to an organic, process-based one (Machado, 2019). | |

| The Crutac Mixed Committee - advanced campus Minter - is created by the Ministério da Educação [Ministry of Education] (MEC). | A work plan is created for institutionalizing and strengthening outreach. | MEC’s measures lead to an “expansion of universities’ action, integrating their faculty into outreach actions” (Anjos, 2014, p. 35, own translation). | |

| 1970-1988 | The Fórum Nacional de Pró-Reitores de Extensão das Universidades Públicas Brasileiras [National Forum of Associate Deans of Outreach of Public Universities] is created (Forproex, 2012). | Outreach as interdisciplinary work for the integral view of social matters (Forproex, 2012). “Inseparability between teaching, research and outreach” (Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988, Art. 207, own translation). Outreach as an educational and interdisciplinary process. | “Creation out of the need for political-institutional institutionalization, since there was a differentiated form, for both funding and guidelines” (Nogueira, 2019, p. 38, own translation, emphasis added). Gatti (2019) highlights the polysemic meaning at the core of concept of outreach. For the author, the way of referring to outreach - process, instrument, and work - has been reformulated and expanded, thus ensuring the “perception that outreach should be understood as an identifying element of the university so that interactions can promote changes in the social environment and in the institution itself” (Gatti, 2019, p. 92, own translation). |

| 1990-2001 | Inclusion into the Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional [National Education Bases and Guidelines Law] (LDB) - Lei n. 9.394 (1996). | Outreach as one of the purposes of the university. | Anjos (2014) points out that it is necessary to assume that this process is not unilateral. It must be built in a “reciprocal relationship where the contexts might be valued in a dialectical movement pervaded by the social reality and by the experience of thinking and doing” (Anjos, 2014, p. 71, own translation). |

| PNE 2001-2010, through Lei n. 10.172, de 9 de dezembro de 2001. | Determines that “at least 10% of credits at undergraduate level in the country are to be reserved for students’ participation on outreach actions” (Lei n. 10.172, 2001, own translation). | It is necessary to recognize this as an achievement by Forproex, since it is one of the first among the 12 actions considered necessary to redefine the public policies aimed at supporting and fomenting these actions. It should also be noted this inclusion into PNE forced institutions not only to rethink their curriculums, but also revise their conception of the inseparability of outreach. |

|

| 2002-2020 | PNE is updated for the period 2011-2010, Projeto de Lei n. 8.035 - B/2010, Lei Ordinária n. 13.005 (2014). | Reference to the form of programs and projects and the connection of activities with the areas of social pertinence (Lei n. 10.172, 2001). | For Machado (2019), this plan points to the offer of outreach courses with academic characteristics, excelling in continuing education. |

| Resolução n. 7 (2018) Conselho Nacional Educação [National Board of Education] (CNE) / Câmara de Educação Superior [Chamber of Higher Education] (CES), which sets the Guidelines for Outreach in Brazilian Higher Education and regulates on the provisions of Goal 12.7 of Lei n. 13.005 (2014). | In Projeto de Lei n. 8.035/2010, among the strategies for higher education, 10% of curriculum credits are secured. This proposition indicates a curriculum-based outreach model, which consists in ensuring its inclusion into the pedagogical plan of courses; efforts are made to consolidate the goals agreed upon over Forproex’s existence - the National Policy on University Outreach. The concept of and guidelines on outreach are updated. | The meaning given by Ribeiro (2019) is that policy on university outreach refers back to the fulfilment of the social and educational function of higher education. By its theoretical-practical nature, it enables a participatory and dialogical form. Thus, “granting curriculum credits becomes a wide curriculum flexibilization process” (Nogueira, 2005, p. 45, own translation). For its framework, he conceives outreach in the curriculum, beyond the idea of a mere squeeze-in, since it is connected with research and therefore part of the knowledge building process. Points to note: the political-educational conception that precedes the term. Introduction of the expressions “higher education institution, knowledge production and application”. |

Source: Authors’ elaboration, with data from the study.

Morin (2016, p. 158, own translation) says that in order to understand a system,

. . . the elements must be defined at the same time in and by the original characteristics, in and with the interrelations they participate in, in and with the perspective of organization they participate in, in and with the perspective of the whole they are integrated into.

Thus can we understand that the words expressed in the documents, actions and engagement of the protagonists - students, the Forproex faculty movement - cannot be seen in isolation. While outreach was constituted as a part of the university’s functions, it comprehends a whole because it is supposed to go beyond the campus, therefore it cannot be seen in isolation. This has been and still is the struggle of the entire pro-outreach community! Understandably, this is a fabric woven with confrontation.

Within governmental policies, we have oscillated between “developmentalist” and instrumental projects and progressive projects. Those who confront these models in a way that is detached from the educational, emancipatory dimension are mistaken. Salles (2020, p. 16, own translation), in reflecting about public university and democracy, says that it is not possible to achieve “academic excellence without deepening social commitment”. Santos (2013, p. 419, own translation), in pointing out the “theses for a university in line with post-modern science”, advocates a structural, operational and subjective change configured by the principle of a “constructive application of science”.

Nogueira (2019, p. 267, own translation) argues that “university outreach is the academic dimension that can pave the way for diversity and interculturality in the university and work as a space of resistance and deconstruction of the logic of colonization”. In turn, Gatti (2019, p. 108, own translation) situates outreach in a position that is “pervaded by ambiguities and contradictions, which have the potential to give rise to critical thinking, to questioning one’s own reality, discussing it, and consequently producing true consciousness”. Moreover, Bonassina (2020, p. 80, own translation) characterizes “university outreach as an instrument of socioenvironmental transformation in cases of social vulnerability”, pointing out that “today’s main challenge for outreach is to rethink the relationship of teaching and research with social needs, to establish the contributions of outreach for strengthening citizenship and actually transforming society”. We can see how these approaches are broad and show richly forms of actions that can be built collectively in processes.

Recognizing that the conceptualizations presented here must find fertile ground so they can be constructed, we build on Santos’ (2013) idea. The author says that it is necessary to give “centrality to outreach” as a foundational point so that this fabric can have a weave that encompasses all discipline components in an interdisciplinary and, why not say, transdisciplinary discussion.

Giving outreach centrality: Pointing out “breaches” in, and closeness with the normative documents

We relate outreach policy to the main points in the normative documents on action. This relationship is built with the guidelines on teacher education curriculums as follows:

in the PNExt/Resolução n. 7, we highlight the concept and guidelines for actions;

in BNCC, “the pedagogical foundations and the specific competencies of mathematics and its technologies for secondary education” (Ministério da Educação, 2018, pp. 99-150, own translation); and

in BNCC-TCT, the “pedagogical presuppositions for approaching the transversal contemporary issues” (Ministério da Educação, 2019, pp. 18-26, own translation).

To advance in the analysis, we initially present the concept that defines outreach actions. Then we highlight terms that are made less visible both in scientific output artifacts, as can be seen in the systematic literature review (SLR), and in discourse about “political entrepreneurship”.7 They cross through discourses about “competencies”, “education quality” and “new education”.

To give visibility and centrality to the discursive lexicon of the constitutional and me- thodological principle of inseparability and of the educational and political dimension, we present the concepts that are found in the documents that institutionalize outreach. They are:

University Outreach also denotes an academic practice to be developed, under the Constitution of 1988, inseparably with Teaching and Research, with a view to promoting and ensuring democratic values, equity, and the development of society in its human, ethical, economic, cultural and social dimensions. (Forproex, 2012, p. 42, own translation).

Outreach in Brazilian Higher Education is the activity that is integrated into the curriculum matrix and organization of research, constituting an interdisciplinary, political-educational, cultural, scientific, and technological process, which promotes transformative integration between higher education institutions and the other sectors of society by means of the production and application of knowledge, in permanent connection with teaching and research. (Resolução n. 7, 2018, pp. 2-3, own translation).

To identify a correlation, we present the foundations and principles on which it was possible to establish a degree of closeness between the concept of outreach and the documents on teacher education in Table 2 below. To that end, we highlighted assertions in the table. We include Resolução n. 2, de 1º de julho de 2015, because we consider that it has not been long enough for teacher education courses to adjust according to the resolutions on the subject that were issued in 2019 and 2020.

Table 2 Diretrizes curriculares nacionais (2015-2020)

| Diretrizes curriculares nacionais (DCN) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Resolução n. 2, de 1º de julho de 2015 DCN on Initial and Continuing Education at the Tertiary Level for Basic Education Teachers |

Resolução n. 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019 BNC-Teacher education |

Resolução n. 1, de 27 de outubro de 2020 BNC-Continuing Education - (2020, pp. 1-72) |

| “Teacher education must ensure the national common base, guided by the conception of education as an emancipatory and permanent process, and by the recognition of the specific nature of teaching, which leads to praxis as an expression of the connection between theory and practice and to the necessary consideration of the reality of basic education institutions’ environments and of the profession” (Resolução n. 2, 2015, p. 5, own translation). It leads the graduate “to pedagogical dynamics that contribute to professional practice and the teacher’s development through a broad view of the education process, its different paces, times and spaces, in relation to the psychosocial, historic-cultural, affective, relational and interactional dimensions that pervade the pedagogical action, enabling critical thinking, problem-solving, collective and interdisciplinary work, creativity, innovation, leadership, and autonomy” (Resolução n. 2, 2015, p. 6, own translation). |

“The connection between theory and practice for teacher education, based on scientific and didactical knowledge, including the inseparability between teaching, research and outreach, in order to ensure the development of students” (Resolução n. 2, 2019, p. 3, own translation). “One of the main guiding marks: using the times and spaces of practice in the areas of knowledge, in the subject matters or in the fields of experience to materialize the commitment to innovative methodologies and interdisciplinary projects, curriculum flexibilization, the construction of educational paths, and students’ life project” (Resolução n. 2, 2019, p. 4, own translation). |

“To ensure the connection between the different continuing education courses and programs and to overcome the fragmentation and absence of connection between different types of knowledge, it is recommended that higher education institutions [HEI] create institutes/integrated units for teacher education whose faculty include not only the institution’s members but also experienced teachers from the school system, thus creating an organic, contextualized bridge between higher education and basic education” (Resolução n. 1, 2020, p. 6, own translation). |

Source: Authors’ elaboration, with data from the study.

We recognize that the terms highlighted are invisible given the predominance of rationalist patterns which are established for teacher education. We highlighted the segment education as an emancipatory, permanent process in order to draw this term off its “hideout” and point it out as a “breach”. In addition, it is possible to build actions implicated with a “horizontal citizenship between citizens”, as argued by Santos (2002). This is an approach that leads to thinking of revaluing the role of the subject who is being educated, who should be socially implicated in the context and “who might promote prudent knowledge for a decent life” (Santos, 2002, p. 280, own translation). In these terms, there is the possibility of a rationality that is critical, educational and closer to humanist principles than to structuralist principles.

Believing that it has not been long enough for the current DCN to materialize in the political-pedagogical projects (PPP) of courses, we show the similarity with the concept of outreach and the openness of this foundation to the possibility of an “impact in the student’s education” (Forproex, 2012, p. 52, own translation). This is because it contains the idea of enabling, through teacher education, “critical thinking, problem-solving, collective and interdisciplinary work, creativity, innovation, leadership, and autonomy” (Resolução n. 2, 2015, p. 6, own translation, emphasis added), which can take place through the horizontal engagement that is present in collective, interdisciplinary and inseparable work.

We also point out some closeness to what the documents say about outreach guiding the interprofessional relationship, which is conceived as a form of reflection and action about the profession, about the problems that involve communities and social groups. In the point highlighted, “a broad view of the education process, its different paces, times and spaces, in relation to the psychosocial, historic-cultural, affective, relational and interactional dimensions that pervade the pedagogical action” (Resolução n. 2, 2015, p. 6, own translation, emphasis added), there are some indications of two epistemological extremes coexisting in DCN. One of them regards the acquisition of knowledge from praxis, as an action-reflection about/in reality, which is connected with the types of knowledge built by experiencing the education process in “its different paces, times”. The other epistemological extreme refers to the integration of these types of knowledge into the educational process (specific knowledge and pedagogical knowledge) and which will form the teacher’s professionality.8 This coexistence enables meeting the interprofessional guideline inasmuch as the complexity of the school’s dynamics is experienced in the student’s education process. This enables mobilizing the knowledge and competencies necessary to build the teacher’s autonomy and identity.

The terms used from a curriculum perspective - education paths, interdisciplinary processes, curriculum flexibilization - are considered as the ones that enable greater closeness to the conception of outreach, as long as it is from the perspective of a “thinking that creates” (Morin, 2015b). Thus, they assume the transposition of discipline limits, and its foundations develop towards the idea of education for autonomy (Freire, 2019b).

To situate quantitatively the similarities, we extracted two matrices, using the tool MAXQDA, based on the mathematical parameters suggested by it. About this analysis, we used as a reference the existence of codes which indicate the conceptual and educational dimension and suggest the expansion of the universe of reference from a theoretical-practical-humanist perspective (a view of the whole - holistic) and the dimension related to the guidelines that can possibly exist in the documents on teacher education and action.

In the literature, we found that the similarity between the analyzed objects can be explained in two ways. One through association with greater positive correlation coefficients, representing greater similarity. The other occurs because the proximity between each pair of objects can assess the similarity, in which the measures of distance or difference are used, and smaller distances represent greater similarity (Assis et al., 2019, p. 146).

We used the measure of similarity indicated in the tool, with the parameter of “Existence of Code that generates a similarity matrix which considers only whether or not the selected codes occur in the document” based on this method:

Simple correspondence = (a + d) / (a + b + c + d) in which the existence and the inexistence are counted as a correspondence. With: a = the number of codes or values of variables which are identical in both documents; d = the number of codes or values of variables which do not exist in both documents; b and c = the number of codes or values that exist in only one document. (MAXQDA, 2020, own translation).

Using the association with greater positive correlation coefficients, representing greater similarity and adopting the tool’s suggestion, we have “value 0 (no similarity) and value 1 (identical). And the closer to 1, the greater the similarity; the farther from 1, the smaller the similarity” (MAXQDA, 2020, own translation)

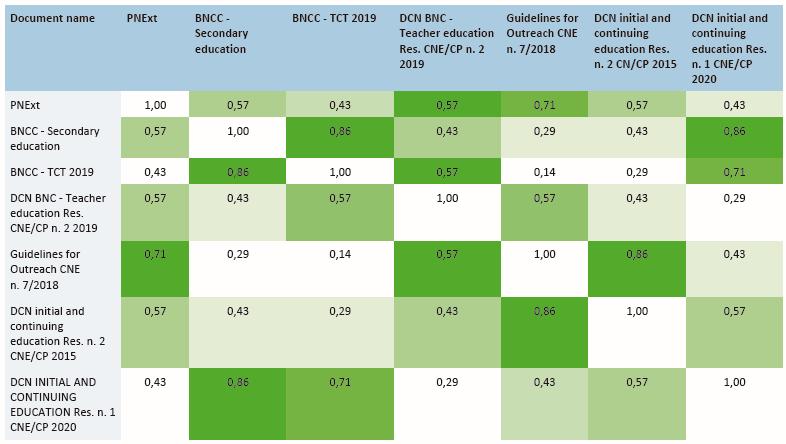

We consider that the less similar they are, the greater the existence of “breaches/detours” which can be used in a critical and creative way to develop outreach actions to their full potential, i.e., with the educational, political and social dimension. In the matrix that contains the conceptual dimension of outreach in correlation with the documents on teacher education and on action, we have the data presented in Figure 1:

Source: Matrix of occurrence of codes viewed by document (MAXQDA, 2020).

Figure 1 Similarity matrix: The context (PNExt) identified with the possible directions for university outreach in education policies

In the categorization of documents, we used the code CExt for concept of university outreach. We adopted the concept that is present in the PNExt (Forproex, 2012) and the updated one, presented by Resolução n. 7, de 18 de dezembro de 2018.

The code DirCamp was employed to define the conceptualizations of university outreach from the perspective of some authors. Nogueira (2019, p. 257) sees it as an academic dimension that can pave the way for diversity and interculturality in higher education, as a space of resistance to the logic of colonization. Gatti (2019) considers outreach as a function that enables transcending the semi-education model.

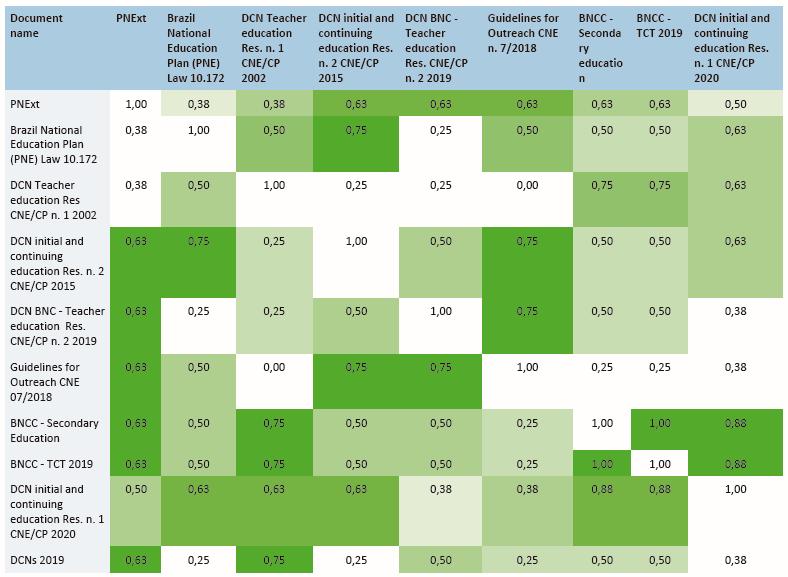

With these references, we consider that, there are terms in the document which are close to the conception of educational and scientific process. On the other hand, there is a distance from the idea of an education process that is educational-political. In the following matrix, in Figure 2, we expand the dimensions of analysis as we confront the documents with the outreach guidelines and principles. To that end, we turned our attention to the connection between teaching-research-outreach, to the dialogical interaction, and to the contribution to a critical-emancipatory teacher education (Resolução n. 7, 2018).

By conducting a demography of the DCN, we sought elements that might reveal not only indicators of existence of the terms, but also a possible equivalence, denoting some closeness with the guidelines’ purpose and with the theoretical framework underpinning the analysis.

In addition to the categorizations presented, we used the following codes: DID, the Interdisciplinarity Guideline, with a methodological approach that consists in integrating discipline concepts in order to reflect and act on the concrete reality of contemporary human needs; DIp, which refers to the Interprofessional Guideline, from the perspective of the types of knowledge and the values that are mobilized during the educational interaction (Fiorentini et al., 1998, p. 309, own translation); Inseparability (Ind), in the sense of the constitutional and methodological principle.

Source: Matrix of occurrence of codes viewed by document (MAXQDA, 2020).

Figure 2 Similarity matrix: Principles and guidelines in relation to the documents on teacher education and on action

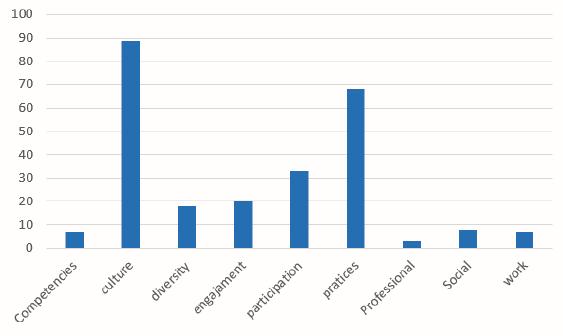

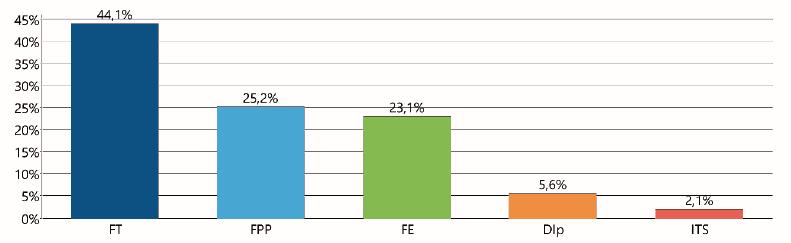

That said, we point out the significant distance between the documents referring to initial and/or continuing education and the PNExt. As an indication, we have the frequency of words used, as shown in Figure 3 below. The terms denoting some closeness with the critical dimension of teacher education appeared with a significantly smaller frequency.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, with data from the study.

Figure 3 Frequency of words: Relationship Concept of Outreach (CExt)

In highlighting the guidelines DId, DID and DIp, we observed that DCN-BNC-Teacher Education shows a considerable distance from these guidelines, and that Resolução n. 2 (2015) shows a relative closeness to them, as presented in Figure 4.

Source: Matrix of occurrence of codes viewed by document (MAXQDA, 2020).

Figure 4 Similarity matrix: Teacher education guidelines

In identifying this distance, we observed that, in the coded segments of Resolução n. 2 (2019, p. 3, own translation), the indication of the “connection between teaching and research with centrality on the teaching-learning process” signals some closeness to the binomial teaching-research, and the exclusion of outreach. This leads us to conclude that while there is the reference to inseparability, there is not, throughout the resolution’s text, directions indicating the inseparability between teaching, research and outreach, as determined by the Constituição Federal [Federal Constitution] (1988).

Another distance indicator regards the use of the distinction between teacher education institutions and higher education institutions. The university is constitutionally qualified to develop teaching, research and outreach actions. The connective “and” grants the meaning of an indissoluble whole. Teaching cannot take place without research or without outreach, contrary to “teacher education institutions”, whose nature is mainly concerned with teaching. Here, there is a clear indication that the bases underpinning the ideal of teacher education are more in line with education as teaching know-how, the overly practical action, than with an education in which teaching, the production of knowledge, research, and the social relevance of that knowledge are subject to a critical construction.

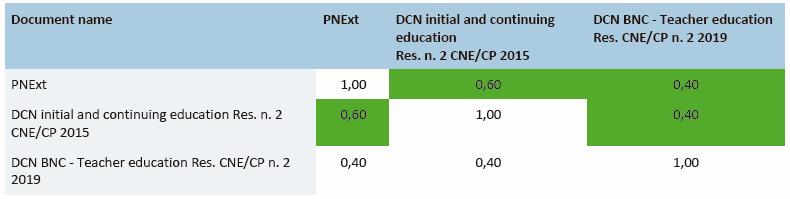

Finally, regarding the indication about the teacher education intended, as shown in Figure 5, such teacher education has a theoretical and practice-oriented nature that is far from the idea of emancipatory, critical education, with values concerned with teacher autonomy.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, with data from the study.

Figure 5 Intended teacher education by the educacional policies

Article 4 of BNC-Teacher Education contains, albeit between the lines, a demand for the development of outreach for teacher education in connection with community demands. Of the competencies presented in the document as fundamental for teachers’ action, only one is directly related to the context of development of the teaching-learning process, determining an engagement with families in order to improve the school environment. Here, it is worth stressing that the focus is only on the teacher-student relationship, and not in a broader view that might denote social engagement as an act of knowledge and awareness raising (Freire, 2019a). A limit is perceived which sets the “attention towards communities” to establish a “good coexistence” between teacher and student.

In the PNExt and in Resolução n. 7, the student’s education is endowed with engagement and critical reflection as complementary poles that contribute to an education in which the principle of autonomy can be experienced in the actions developed. Thus, this policy determines as a contribution to the student’s education the expansion of their universe of reference through direct contact with contemporary issues.

Figure 6 below shows the segments with codes that indicate the education presuppositions in the teacher education policies.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, with data from the study.

Figure 6 Segments with codes: The formative assumptions of training policies

The data of Figure 6 confirms what was pointed out by the analyses of this instrument, carried out by Silva (2020), Lima and Sena (2020), and Nogueira and Borges (2021), about the fact that the technical and professionalizing dimensions are far from education questions that enable a more critical education. This dissimilarity of BNC-Teacher Education and BNC-Continuing Education from dimensions that contribute to a more humanist education, advocated by the PNExt, can be considered as a gap to be bridged by another rationality. We consider that the lack of an initial education where macrostructural questions are present, which takes into account the more humanizing dimensions of teacher education, impacts directly on basic education teaching. In other words, if students undergoing initial teacher education only develop operating techniques, in thinking of an outreach action, they will also tend to develop actions that are merely technical, far from a critical-reflective role. We stress the need for the development of mathematical, linguistic and scientific competencies to be connected with social, environmental, cultural, economic and political issues. This dissociation characterizes a state of semi-education (Adorno, 1995) which does not contribute to an education for autonomy and social commitment.

Going against this teacher education model, we can see that BNCC-TCT (Ministério da Educação, 2019) is very close to the idea of a theoretical-practical-humanist education. This opens the possibility for collaborative work with the school to transcend the logic and parameters provided by the instrumental logic underpinning the documents on teacher education and action.

Another point to be noted is the acronym BNCC - which precedes the expression transversal contemporary issues (TCT) - an indication of the prevailing standard - the foundation of competencies and skills and the consideration that these take on greater importance in the assess-ment documents. This points to another dimension of the teacher’s work: reconciling the assessment demands that follow international standards and developing actions with a humanist dimension. In addition, teacher education is faced with the challenge of building an organic relationship between humanist critical presuppositions, which is necessary to an education for autonomy and requires a praxis that encompasses the theory-practice unity.

This analysis corroborates what Hage et al. (2020) and Silva (2020) point out about the fact that the overly technical conception of action and teacher education is the key measure to consolidate the ideology of a knowledge society, which prioritizes competencies and skills for employability and homogenizes the knowledge taught in school, without considering the different realities. This reveals the consolidation of an education where the prevalent idea is to prepare a “self-programming workforce to meet the demands of time and space, and on the other hand a generic workforce” (Castells, 2018, p. 135, own translation) adjusted to an economic system that is informational and global. It rests on educators to build another path. And that path is made through resistance and the exercise of critical and creative thinking.

Final considerations

In this study, we sought to build a correlation between the documents that found university outreach and the ones that inform teacher education and action in basic education. We pointed out some closeness to technical and professionalizing dimensions and the distance from more critical and emancipatory dimensions which allow individuals undergoing teacher education to expand their references beyond the principle of “know-how”. We emphasized that the counterpoint to this teacher education model is in the policy on university outreach.

In examining the dissimilarities between the documents, we sought the “terms made less visible” and found their closeness to the social, critical and humanizing principles advocated in the university outreach policy. We believe that, in this way, it is possible to start a movement of “creative actions” to the educational policy in effect. To that end, we opened the possibility of building a new rationality through university outreach as a systemic process that enables teacher education actions that can change the connection between university and school.

The analyses we conducted showed us distances between the normative documents on teacher education. For example, Resolução n. 2/2015 preconizes an organic relationship between initial and continuing teacher education, which means greater connection with basic education. On the other hand, Resolução n. 2/2019 addresses only initial education and indicates as an education principle a linear and overly practical bias. Therefore, in the field of teacher education, these documents direct the design of political-pedagogical projects and, considering that it has not been long enough for the necessary updating, there is an open door for the principles and dimensions of university outreach policy to be more extensively experienced, debated and consolidated in these arenas.

We consider that the dissimilarities between the documents BNCC, BNC-Teacher Education and BNC-Continuing Education place them far from the principles of university outreach, which are theoretically founded on the idea of education for autonomy and social commitment. Our findings revealed that the idea of an education of the student for professional practice is in line with that of technical education, not with critical education. We saw that there is a “good policy” in BNCC as it is complemented by BNCC-TCT, which is closer to an approach to teacher education as comprehension of reality. A seeming “good policy” poses another challenge to basic education and to teacher educators as it increases the university’s responsibility towards the school and towards initial and continuing teacher education.

That said, we list as “breaches” that must be closed:

separation between initial and continuing education;

departure from the constitutional principle of inseparability;

the excessive focus on pragmatism;

the discrepancy from policies already instituted;

the discrepancy from an agenda of social transformation, in this case, for emancipatory purposes;

the discrepancy from a teacher education in which the humanist dimension of living is not reduced to utility and economy.

Given this scenario of educational policies that poses know-how as a fundamental principle, we propose for the terms that are made less visible in these policies to be considered as central for countering an overly practical model. To that end, we propose a “new rationality” via university outreach which brings into the context of teacher education and action in basic education other types of knowledge and other ways of being and thinking about the world. Thus, we propose for the development of mathematical, linguistic and scientific competencies to be integrated with social, environmental and cultural questions. This presupposes building “another rationality” for the curriculum components of teacher education courses, and an “open rationality” in the actions and disciplines of basic education. We suggest for this “new rationality” to be materialized via university outreach.

Data availability statement

The data underlying the research text are informed in the article.

REFERENCES

Adorno, T. (1995). Educação e emancipação. Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Anjos, M. D. C. R. (2014). Fronteiras na construção e socialização do conhecimento científico e tecnológico: Um olhar para a extensão universitária [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Científica e Tecnológica. [ Links ]

Antunes, R. (2018). O privilégio da servidão: O novo proletariado de serviços na era digital. Boitempo. [ Links ]

Assis, J. P., Sousa, R. P., & Dias, C. T. S. (2019). Glossário de estatística. Edufersa. [ Links ]

Ball, S. J. (2011). Sociologia das políticas educacionais e pesquisa crítico-social: Uma revisão pessoal das políticas educacionais e da pesquisa em política educacional. In S. J. Ball, & J. Mainardes (Orgs.), Políticas educacionais: Questões e dilemas (pp. 21-53). Cortez. [ Links ]

Ball, S. J., & Mainardes, J. (Orgs.). (2011). Políticas educacionais: Questões e dilemas. Cortez. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2016). Análise de conteúdo. Edições 70. [ Links ]

Bazzo, V., & Scheibe, L. (2020). De volta para o futuro: Retrocessos na atual política de formação docente. Retratos da Escola, 13(27), 669-684. https://doi.org/10.22420/rde.v13i27.1038 [ Links ]

Bonassina, A. L. B. (2020). A extensão universitária como instrumento de transformação socioambiental nos casos de vulnerabilidade social [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade do Vale do Itajaí, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência e Tecnologia Ambiental. [ Links ]

Botomé, S. P. (1996). Pesquisa alienada e ensino alienante: O equívoco da extensão universitária. Vozes. [ Links ]

Candau, V. M. (1999). Reformas educacionais hoje na América Latina. In A. F. B. Moreira (Org.), Currículo: Políticas e práticas (pp. 29-42). Papirus. [ Links ]

Castells, M. (2018). A sociedade em rede (19a ed.). Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Castro, M. C. S. (2022). Ecologia cognitiva da extensão universitária: Encontro, diálogo e colaboração [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade Federal da Bahia. [ Links ]

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. (1988). Brasília, DF. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm [ Links ]

Costa, E. M., Mattos, C. C., & Caetano, V. N. S. (2021). Implicações da BNC-Formação para a universidade pública e formação docente. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, 16(especial 1), 896-909. https://periodicos.fclar.unesp.br/iberoamericana/article/view/14924 [ Links ]

Fiorentini, D., & Souza, A. J. de, Jr., & Mello, G. F. A. de. (1998). Saberes docentes: Um desafio para acadêmicos e práticos. In C. M. G. Geraldi, D. Fiorentini, & E. M. A. Pereira (Orgs.), Cartografias do trabalho docente: Professor(a) pesquisador(a) (pp. 307-335). Mercado das Letras. [ Links ]

Fórum de Pró-Reitores de Extensão das Instituições Públicas de Educação Superior Brasileiras (Forproex). (2012). Política Nacional de Extensão Universitária. UFPE. https://proex.ufsc.br/files/2016/04/Pol%C3%ADtica-Nacional-de-Extens%C3%A3o-Universit%C3%A1ria-e-book.pdf [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2019a). Educação e mudança. Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Freire, P. (2019b). Pedagogia da autonomia: Saberes necessários à prática educativa. Paz e Terra. [ Links ]

Frigotto, G., & Ciavatta, M. (2011). Perspectivas sociais e políticas da formação de nível médio: Avanços e entraves nas suas modalidades. Educação & Sociedade, 32(116), 619-638. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302011000300002 [ Links ]

Gadotti, M. (2017). Extensão universitária: Para quê? Instituto Paulo Freire. [ Links ]

Gatti, J. P. (2019). Extensão universitária no Brasil: A experiência formativa na área de educação da UFSCar [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade Federal de São Carlos. [ Links ]

Gorzoni, S. D., & Davis, C. (2017). O conceito de profissionalidade docente nos estudos mais recentes. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 47(166), 1396-1413. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053144311 [ Links ]

Hage, S. A. M., Camargo, R. K., Figueiredo., A. M. et al. (2020). BNCC e BNCF: Padronização para o controle político da docência, do conhecimento e da afirmação das identidades. In A. M. C. Uchoa, Á. M. Lima, & I. P. F. S. Sena (Orgs.), Diálogos críticos: Reformas educacionais: Avanço ou precarização da educação pública? (vol. 2, pp. 142-178). Fi. [ Links ]

Lei n. 5.540, de 28 de novembro de 1968. (1968). Fixa normas de organização e funcionamento do ensino superior e sua articulação com a escola média, e dá outras providências. Câmara dos Deputados, Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. (1996). Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Presidência da República, Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Lei n. 10.172, de 9 de janeiro de 2001. (2001). Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação e dá outras providências. Presidência da República, Brasília, DF. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10172.htm [ Links ]

Lei n. 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. (2014). Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação PNE e dá outras providencias. Presidência da República, Brasília, DF. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm [ Links ]

Lima, A. de M., & Sena, I. P. F. S. (2020). A pedagogia das competências na BNCC e na proposta da BNC de formação de professores: A grande cartada para uma adaptação massiva da educação à ideologia do capital. In A. M. C. Uchoa, Á. M. Lima, & I. P. F. S. Sena (Orgs.), Diálogos críticos: Reformas educacionais: Avanço ou precarização da educação pública? (vol. 2, pp. 11-37). Fi. [ Links ]

Machado, K. A. (2019). Formação docente e extensão universitária: Tessituras entre concepções, sentidos e construções [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade de Brasília, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. [ Links ]

MAXQDA. (2020). MAXQDA, by Verbi. www.maxqda.com [ Links ]

Ministério da Educação. (2018). Base Nacional Comum Curricular: Ensino Médio. MEC/SEB. http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/historico/BNCC_EnsinoMedio_embaixa_site_110518.pdf [ Links ]

Ministério da Educação. (2019). Temas contemporâneos transversais na BNCC: Proposta de práticas de implementação. MEC/SEB. http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/implementacao/guia_pratico_temas_contemporaneos.pdf [ Links ]

Morin, E. (2015a). O método 2: A vida da vida (5a ed.). Sulina. [ Links ]

Morin, E. (2015b). O método 3: O conhecimento do conhecimento. Sulina. [ Links ]

Morin, E. (2016). O método 1: A natureza da natureza. Sulina. [ Links ]

Nogueira, A. L., & Borges, M. C. (2021). A BNC-Formação e a formação continuada de professores. Revista On-line de Política e Gestão Educacional, 25(1), 188-201. https://doi.org/10.22633/rpge.v25i1.13875 [ Links ]

Nogueira, M. D. P. (2005). Políticas de extensão universitária brasileira. UFMG. [ Links ]

Nogueira, M. D. P. (2019). A participação da extensão universitária no processo de descolonização do pensamento e valorização dos saberes na América Latina [Tese de doutorado]. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. [ Links ]

Pêcheux, M. (1987). O discurso: Estrutura ou acontecimento. Pontes. [ Links ]

Resolução n. 2, de 1º de julho 2015. (2015). Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação inicial em nível superior (cursos de licenciatura, cursos de formação pedagógica para graduados e cursos de segunda licenciatura) e para a formação continuada. Brasília, DF. http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=136731-rcp002-15-1&category_slug=dezembro-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

Resolução n. 7, de 18 de dezembro de 2018. (2018). Estabelece as Diretrizes para a Extensão na Educação Superior Brasileira e regimenta o disposto na Meta 12.7 da Lei n. 13.005/2014, que aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE 2014-2024 e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF. https://normativasconselhos.mec.gov.br/normativa/view/CNE_RES_CNECESN72018.pdf [ Links ]

Resolução n. 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019. (2019). Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e institui a Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação). Brasília, DF. http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=135951- rcp002-19&category_slug=dezembro-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192 [ Links ]

Resolução n. 1, de 27 de outubro de 2020. (2020). Dispõe sobre as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Continuada de Professores da Educação Básica e institui a Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Continuada de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação Continuada). Brasília, DF. [ Links ]

Ribeiro, R. M. C. (2019). As bases institucionais da política de extensão universitária: entendendo as propostas de universidades federais nos planos de desenvolvimento institucional. Revista Internacional de Educação Superior, 5, Artigo e019021. https://doi.org/10.20396/riesup.v5i0.8652870 [ Links ]

Salles, J. C. (2020). Universidade pública e democracia. Boitempo. [ Links ]

Santos, B. S. (2002). Para uma sociologia das ausências e das emergências. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, (63), 237-280. https://doi.org/10.4000/rccs.1285 [ Links ]

Santos, B. S. (2011). A Universidade do século XXI: Para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da universidade. Cortez. [ Links ]

Santos, B. S. (2013). Pela mão de Alice: O social e o político na pós-modernidade (13a ed.). Cortez. [ Links ]

Silva, K. A. C. P. C. da. (2020). Formação de professores na Base Nacional Comum Curricular. In A. M. C. Uchoa, Á. M. Lima, & I. P. F. S. Sena (Orgs.), Diálogos críticos: Reformas educacionais: Avanço ou precarização da educação pública? (vol. 2, pp. 102-121). Fi. [ Links ]

Teixeira, A. (1964). A universidade de ontem e de hoje. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, 42(95), 27-47. http://www.bvanisioteixeira.ufba.br/fran/artigos/ontem.html [ Links ]

1This article corresponds to chapter IV of the doctoral thesis Ecologia cognitiva da extensão universitária: Encontro, diálogo e colaboração (Castro, 2022), defended within the scope of the Doctoral Program in Knowledge Dissemination. We emphasize that the thesis was constructed in the multipaper format, in which each chapter corresponds to a specific objective of the research and, in a dialogic way, builds knowledge about the object of the study. We understand that this format enables an expanded dialogue with the object of the research developed and a wide dissemination of the knowledge produced.

2Teixeira (1964, pp. 27-37, own translation), in pointing out the transformations that happened over the history of this institution (1852-1914; 1930, with the Second World War, until the present), delimits not only the break with isolation, but also the “mingling with present life”, making it marked by its “pluralism and extreme confusion and divisionism”.

3The author exemplifies this possibility of reversing specialization using evidence from processes of despecialization/re/specialization in insect societies, more specifically “sucker bees in the center of a hive” (Morin, 2015b, p. 345, own translation).

4For Morin (2015b), life and death are eco-dependent, and should be conceived intensively in their contradictory, ever changing processes, in their complexity. The author considers that life is not conceived only from the physical-biological perspective, but in a sense that encompasses the anthropo-social perspective to living. The notion of life should be conceived intensively in its focus, the living individual - and extensively - in its totality of biosphere, in its primary and fundamental organization - the cell - and in all forms of organization (multicellular, societies, ecosystems) (Morin, 2015b, p. 392).

5For Pêcheux (1987, p. 60, own translation), the classic science of language intended to be the “science of expression and the science of the means of that expression”. According to the author, the “conceptual displacement introduced by Saussure, through the separation of the homogeneity between language theory and practice” (pp. 60-61, own translation) left uncovered the terrain where language practice and theory sought to answer questions about the text’s semantic, syntactic and purpose-related usages.

6Records of the lesson of the discipline Text Analyses in the Production of Qualitative Results, taught by Professor José Luís Michinel, in the first semester of 2018, where a CA exercise with a text by Klaus Krippendorff was presented.

7Ball (2011, pp. 91-92) conceptualizes the term based on the assertion that some areas use educational studies not subject to academic or scientific erudition and which are used with certain interests of entrepreneurs. For the author, the political entrepreneur is committed to applying technical solutions, organizations or contexts which are considered a priori as necessary to structural and/or cultural change.

Received: November 07, 2022; Accepted: March 30, 2023

text in

text in