Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação e Realidade

versión impresa ISSN 0100-3143versión On-line ISSN 2175-6236

Educ. Real. vol.49 Porto Alegre 2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-6236136476vs01

OTHER THEMES

Plagiarism from the Perspective of Distance Higher Education Students

Ligia Maria Barrios Campanhão holds a degree in Biological Sciences, as well as a Master and PhD in Environmental Engineering Sciences from the University of São Paulo (USP). She is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp). She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ), USP.

I http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5388-4311

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5388-4311

Bruno Cesar Cassani Medeiros holds a degree in Economics, as well as a Master in Economic Development from the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). He is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp). He is currently a PhD candidate in Economic Development at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp).

II http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4485-2833

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4485-2833

Stefanny Batista dos Santos holds a degree in History, as well as a Master in Social History from the University of São Paulo (USP). She is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp).

I http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6934-4755

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6934-4755

Ana Yenny Molleapaza Tito holds a degree in Materials Engineering, as well as a Master in Materials Engineering from the University of São Paulo (USP). She is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp). She is currently a PhD candidate in Materials Engineering at the São Carlos School of Engineering (EESC), USP.

I http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2781-7913

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2781-7913

Ana Paula Curcio holds a degree in Chemistry, as well as a Master in Nuclear Technology – Materials from the Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN). She is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp).

I http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5393-0349

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5393-0349

Juliana Morais Belo holds a degree in Language and Literature, as well as a Master in Literary Theory and History from the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). She is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp). She is currently a PhD candidate in Literary Theory and History at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp).

II http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3318-7564

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3318-7564

Luís Eduardo Santos Pereira holds a degree in Language and Literature, as well as a PhD in Linguistics and Portuguese Language from the State University of São Paulo (Unesp). He is also a specialist in Didactic-Pedagogical Training for Distance Education from the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp).

III http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7366-2935

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7366-2935

Celia Maria Haas holds a degree in Pedagogy, as well as PhD in Education from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC/SP). She is currently a Full Professor at the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp).

IV http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8462-8350

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8462-8350

IUniversidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo/SP – Brasil

IIUniversidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas/SP – Brasil

IIIUniversidade Estadual Paulista ‘Julio de Mesquita Filho’ (UNESP), São Paulo/SP–Brasil

IVUniversidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo (UNIVESP), São Paulo/SP – Brasil

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge of plagiarism among undergraduate students at a distance education university. A questionnaire was applied to the students, and the content of two courses and institutional documents were analyzed to identify guidelines regarding plagiarism. Plagiarism was not discussed in the courses, and institutional documents provided inconsistent guidance on how to address it. Although students claim to know what plagiarism is, the majority associate it solely with copying content without proper referencing or citation. According to the students, the main reasons leading to plagiarism are a lack of organization and motivation for studying, and a lack of skills for academic writing.

Keywords Plagiarism; Scientific Writing; Undergraduate Students; Higher Education; Distance Education

Este estudo teve como objetivo investigar o conhecimento do plágio por alunos de uma universidade de educação a distância. Para isso, aplicou-se um questionário aos alunos e analisaram-se os conteúdos de duas disciplinas e de documentos institucionais para identificar orientações sobre o plágio. Nas disciplinas o tema não é discutido e os documentos internos apresentaram orientações inconsistentes sobre o seu enfrentamento. Embora os alunos afirmem saber o que é plágio, a maioria o associa unicamente à cópia de conteúdo sem a devida referência ou citação. Segundo os alunos, os motivos principais que levam ao plágio são a falta de organização e motivação para os estudos e de competências e habilidades na escrita acadêmica.

Palavras-chave Plágio; Escrita Científica; Estudantes Universitários; Educação Superior; Educação a Distância

Introduction

Plagiarism in academia is not only unethical but also illegal and immoral since it involves the unauthorized appropriation of another individual's work. According to the code of conduct of the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), plagiarism is defined as “the use of ideas or verbal, oral, or written formulations of others without giving them due credit, in a way that reasonably creates the perception that they are the original ideas or formulations of the person using them.” (FAPESP, 2014, p. 31). In Brazil, plagiarism is a crime under Law No. 9,610/98 (Brasil, 1998), which regulates copyright, and under Article 184 of the Penal Code (Brasil, 2003).

Plagiarism presents a significant challenge in various higher education institutions and manifests in various forms. Krokoscz (2012) classifies plagiarism as i) direct – a literal copy of text without appropriate citation; ii) indirect – where ideas are reproduced; iii) mosaic – which reproduces fragments from multiple sources; iv) consensual – attributing authorship to individuals who did not contribute to the work; v) cliché – the use of well-known catchphrases created by other authors; vi) source – the presentation of citations from other works without proper consultation of the original sources; and vii) self-plagiarism – the reuse of one’s own previously published work without appropriate self-citation.

There are several possible causes for the appropriation of ideas without proper citation by higher education students. Hafsa (2021) identifies the main factors as follows: a lack of ethical standards among students; difficulties with time management associated with demanding schedules; procrastination; difficulty with academic writing; deficiencies in foreign language proficiency; and institutional shortcomings, such as insufficient explicit instructions and inadequate punitive measures. While the phenomenon is widespread, the possible causes are numerous, complicating a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. Seitenfus et al. (2019) further suggest that a lack of knowledge about citation norms and an inability to detect plagiarism in its various forms may lead distance education students to commit plagiarism. Consequently, plagiarism may be committed unintentionally rather than deliberately.

Distance education is situated within a digital and digitized world, where access to information is increasingly democratized, combined with the almost immediate ease of searching for texts and publications. Therefore, analyzing the relationship between students and plagiarism is even more necessary, as the internet proves to be a convenient tool for higher education students to commit plagiarism (Selwyn, 2008). Furthermore, distance education has become prevalent in Brazil, since between 2011 and 2021 there was a 474% increase in the number of new students enrolling in distance education programs, and they currently represent the majority of higher education enrollees (INEP, 2021).

This study focuses on the occurrence of plagiarism in academic and scientific writing among undergraduate distance education students. Rather than a general and detached study of students' experiences, this research aims to understand their perspective, who are more or less critical and familiar with digital technologies in a research context. We analyzed the Virtual University of the State of São Paulo (Univesp), a higher education institution founded in 2012 that offers distance education undergraduate programs to approximately 48,000 people (Univesp, 2021e). Most students come from public schools in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, and a significant portion are responsible for the family income (Univesp, 2021e).

While there is research on the incidence of plagiarism among students at traditional in-person higher education institutions (Barbastefano; de Souza, 2008; Lima, 2019; Ramos; Morais, 2021; Gomes; Menezes, 2022), few studies evaluate distance education institutions (e.g., Batistela, 2013; Seitenfus et al., 2019). To date, there has been no documented research on plagiarism in academic work produced by undergraduate students at Univesp. As a public institution that exclusively offers distance education programs, this study contributes to a necessary research agenda focused on plagiarism, one of the factors that undermine the quality of distance education programs (Ferreira; Mourão, 2020).

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge of plagiarism among undergraduate students and its occurrence in academic work at Univesp. To achieve this, the specific objectives were: i) to identify the guidelines the University provides to students and staff regarding plagiarism in academic work; and ii) to investigate the causes that lead to plagiarism in students’ academic work.

To identify the University's conduct on plagiarism, institutional documents and the content of two courses on text production and scientific methodology were analyzed. Data on undergraduate students' perceptions was collected through a questionnaire about the meaning and their experiences with plagiarism. The guidelines from the documents and courses were then compared with the students' perceptions and attitudes toward plagiarism.

Methods

The Fundação Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo (Univesp), maintained by the government of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, was established in 2012 as a distance education institution. Currently, it offers nine undergraduate programs—teaching degrees in Language and Literature, Mathematics, and Pedagogy; bachelor’s degrees in Information Technology, Data Science, Computer Engineering, Administration, and Production Engineering; and an Associate degree in Management Processes. In 2021, 48,131 undergraduate students were enrolled, with most new entrants that year being the first generation of university students in their families and coming from public schools. Additionally, 43% identified as Black, Brown, or Indigenous, and 37% were responsible for their family’s income (Univesp, 2021e).

The University currently offers a range of academic activities, including regular courses, the Integrative Project (PI), mandatory and optional internships, and the Undergraduate Thesis (TCC). The PI is a curricular component designed to facilitate active, group-based research, aimed at developing solutions for real-world problems pertinent to students' professional fields. Evaluation of the PI involves the preparation of reports formatted like technical-scientific papers. Internships involve supervised practical experience in a professional setting and require the submission of reports. The TCC is a compulsory curricular component that involves creating and defending a scientific study before an examining committee.

The technical-pedagogical team at the University consists of professors, supervisors, mediators, facilitators, and external collaborators from other universities involved in course development. Professors are responsible for planning, developing, supervising, and evaluating the University's pedagogical activities. Course authors are responsible for creating and selecting content and recording video lessons. Supervisors oversee the academic activities conducted by mediators and facilitators. Mediators are responsible for on-site activities at study centers, with a particular focus on the PI. Facilitators, in turn, maintain asynchronous and synchronous virtual interactions with students and are responsible for answering queries, moderating forums, grading assignments and exams, and mentoring students through the PI and TCC. Therefore, facilitators are involved in all curricular components. Mediators are staff members and work 40 hours a week, while facilitators are master’s and PhD students from public universities in São Paulo who work as scholarship holders at Univesp. Facilitators are enrolled in a specialization course on distance education practice and dedicate 8 hours a week to monitoring student activities as part of their professional development.

In 2021, the University employed 119 mediators and 2,054 facilitators (Univesp, 2021e). In regular courses, synchronous support is provided through weekly 1-hour meetings between facilitators and students. For the PI, synchronous support consists of biweekly 1-hour group meetings, with each facilitator overseeing approximately 10 groups of 5-7 students. Mediators, on the other hand, supervise about 40 groups of 5-7 students, holding biweekly 1-hour meetings for each group. During the development of the TCC, each facilitator supervises about six groups of 5-8 students, with biweekly follow-up meetings lasting about 1 hour. Overall, mediators guide approximately 280 students during the PI, while facilitators guide about 70. For the TCC, facilitators supervise about 48 students.

Analysis of Course Content and Institutional Documents

Institutional documents governing regular courses, the Integrative Project (PI), internships, and the Undergraduate Thesis (TCC) were analyzed to identify the existence of plagiarism guidelines directed at students and tutors (Chart 1). Additionally, the content of two courses offered to students in the second semester of 2021, Projects and Methods for Knowledge Production and Reading and Text Production, was examined.

Chart 1 Institutional documents with rules and guidelines for regular courses, internships, Integrative Project, and Undergraduate Thesis

| DOCUMENT TITLE | DATE | TARGET AUDIENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Work Standardization Manual | 2018 | All students |

| Academic Rules | August 2019 | All students |

| General Guidelines for Participation and Evaluation | 2019 | Students enrolled in regular courses |

| Internship Regulations | December 2019 | Students enrolled taking an internship |

| Undergraduate Thesis Regulations | April 2020 | Students enrolled in the Undergraduate Thesis course |

| Manual for Undergraduate Thesis supervisors | 2021 | Facilitators and mediators assigned as Undergraduate Thesis supervisors |

| Guidelines for Integrative Project Evaluation | January 2021 | Students enrolled in the Integrative Project |

| Guidelines for Integrative Project Follow-Up | January 2021 | Facilitators and mediators assigned as supervisors in the Integrative Project |

| Guidelines for Integrative Project students | January 2021 | Students enrolled in the Integrative Project |

| Guidelines for Submitting the Integrative Project | January 2021 | Students enrolled in the Integrative Project |

| Frequently Asked Questions about the Integrative Project | 1st semester 2021 | Facilitators and mediators assigned as supervisors in the Integrative Project |

| Integrative Project Regulations | January 2021 | Students enrolled in the Integrative Project |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Questionnaire Administered to Undergraduate Students

A questionnaire comprising 17 closed-ended and two open-ended questions1 was developed to collect data on students' understanding of plagiarism and its implications (Supplementary Material). The questionnaire is organized into five sections, addressing plagiarism from cognitive (awareness of what plagiarism is), ethical (understanding the implications of plagiarism), and reflective (personal views and explanations for its occurrence) perspectives. The questionnaire investigated the occurrence of plagiarism in students' academic activities, the role of tutors in mediating plagiarism, the relevance of reasons for plagiarism as described in the literature, students' proficiency in academic writing, and their opinions on measures for penalizing and preventing plagiarism. The questionnaire was created using Google Forms and distributed via a link posted in the announcements section of the virtual learning environment (AVA), which is accessible to all Univesp students. Data collection took place from October 4 to October 25, 2021. A total of 815 valid responses were received from the 48,131 undergraduate students enrolled in 2021, reflecting a participation rate of approximately 1.7% of the student body.

The data were analyzed using quantitative and qualitative techniques to identify trends and patterns, allowing for broad and objective statements about the sampled population. On the other hand, unique responses were emphasized to highlight variables that are crucial for understanding and questioning standardized trends. This approach aimed to uncover information that was not captured or fully understood through the close-ended questions. Therefore, data collection involved a balance between objective measures and discursive elaboration. Responses to close-ended questions were summarized using descriptive statistics and visualized through graphs. The responses to open-ended questions were compiled, coded, and categorized following a qualitative data analysis methodology (Gibbs, 2009). After categorization, the frequency of mentions for each identified category was obtained.

Results and Discussion

Analysis of Course Content and Institutional Documents

The two courses under examination are part of the core curriculum for all programs and aim to introduce students to the fundamentals of academic writing and methodology, including conventions and ethical issues. Our analysis will concentrate specifically on the course Projects and Methods for Knowledge Production, as plagiarism and related topics were not covered in the Reading and Text Production course. Although the Projects and Methods course primarily discusses methodology and the presentation of scientific work, plagiarism is only briefly mentioned in the context of academic norms and ethics. The following paragraphs detail how plagiarism is addressed and discussed with undergraduate students in this course.

In a video lesson (Organização, 2021) focused on citation norms, plagiarism, its definition, and strategies for avoiding it are not addressed. This course, offered at the beginning of the program, represents a critical opportunity to introduce and discuss these topics, especially given the students' demands for institutional treatment of plagiarism, as highlighted in the next section. Plagiarism is also absent from the course’s reference materials, such as the citation style guidelines provided by São Paulo State University (UNESP, 2020). In the content on Rigor and Ethics in Research, a video lesson covers principles such as consent, reliability, anonymity, and data protection, but does not discuss originality or plagiarism (A comunicação, 2021).

There are two noteworthy approaches in this course. First, a discussion forum titled Copying without citing the source is an error (A cópia, 2021) encourages students to reflect on the implications of copying texts in academia. However, the word plagiarism is not used in the forum's introductory text, it only appears in the comments of some students who correctly associate unreferenced copying with plagiarism, citing ethical and legal implications. Additionally, out of the 11 forums available, eight were not moderated by tutors. Consequently, a space intended for thoughtful reflection was underutilized and became a repository of comments based on personal experiences – mostly supported by common sense. Many of these comments justified or normalized the practice of unreferenced copying, as suggested by one student: “If words exist, do they have an owner?” (A cópia, 2021).

Another approach is a practice exercise for academic rewriting that aims to “[...] present a step-by-step guide on how to rewrite what you have read.” (Univesp, 2019b). The resource includes a reminder in its introduction: “[...] it is important to never forget to inform who is the author of the idea you are presenting. Quoting someone’s idea, directly or indirectly, without stating who the author is, is plagiarism.” (Univesp, 2019b). This is the first instance where incoming students are introduced to the concept of plagiarism, though the resource does not discuss it as an academic practice or address its legal implications.

The exercise consists of a four-step guide designed to teach techniques for rewriting excerpts from other texts. However, because plagiarism is not thoroughly addressed, the exercise risks becoming a technical tool that may inadvertently facilitate the copying of excerpts and ideas, rather than teaching students how to creatively engage with and transform the ideas of others. The exercise suggests fundamental changes such as replacing words with synonyms, altering sentence structure and order, and modifying verb tenses, which mainly involve adapting the copied text with different words. While this exercise is useful for practicing rewriting, it ultimately promotes paraphrasing rather than encouraging true intertextuality and original writing. As will be discussed further, paraphrasing, in addition to being a general problem associated with plagiarism (Diniz; Terra, 2014), is also a recurring practice among the interviewed students, who believe that such adaptations are sufficient to produce original work or, at worst, avoid detection by plagiarism software.

The institutional documents for the PI, Internship, and TCC offer a few ambiguous guidelines on plagiarism and its implications. This lack of clarity not only reveals a significant gap in addressing the issue but also reflects a tolerance of practices that complicate both the evaluation and penalization of plagiarism. The Undergraduate Thesis Regulations document (Univesp, 2020) mentions that copying previously published works is plagiarism under copyright law, with a stipulation for immediate failure if students engage in such practices. However, the document does not provide detailed criteria for what constitutes plagiarism, merely referencing the applicable copyright law. Similarly, in the Integrative Project Regulations (Univesp, 2021c), plagiarism is cited as a criterion for automatic failure. In contrast, the Guidelines for Integrative Project students (Univesp, 2021b) indicate that plagiarism may lead to grade deductions or failure, depending on the degree of similarity identified.

There is also ambiguity in how plagiarism issues are addressed, as well as the delegation of responsibility to tutors, as detailed below. As highlighted in the course content analysis, plagiarism is not actively discussed with students. The Manual for Undergraduate Thesis supervisors indicates that “[...] it is the supervisor’s responsibility to identify instances of plagiarism during the work development process and to suggest pedagogically guided solutions based on bibliographic references, aiming to avoid plagiarism in the final version as much as possible.” (Univesp, 2021a, p. 3). Additionally, these guidelines seem inconsistent with the Academic Rules provided to students and facilitators/mediators. Although that document does not explicitly mention plagiarism, referring to it as content similarity, it warns students about potential penalties while instructing tutors to deduct points “[...] depending on the degree of similarity, [...]” (Univesp, 2019a, p. 6) rather than failing the student. The lack of clear institutional policies for addressing plagiarism has been previously identified in other in-person and distance education institutions (Seitenfus et al., 2019; Gomes; Menezes, 2022), bringing insecurity to educators regarding actions to combat plagiarism (Seitenfus et al., 2019).

Two key conclusions emerge from the analysis. First, there is a noticeable lack of clear and objective discussions about plagiarism within the courses focused on reading, writing, and scientific methodology, which could help clarify both technical and ethical issues related to the topic. Second, institutional documents exhibit inconsistency in their treatment of plagiarism: while some documents explicitly condemn plagiarism and prescribe automatic failure, others consider it a lesser issue, resulting in only grade deductions. It is evident that the university is ineffective in combating plagiarism, both through educational efforts and the implementation of a clear and comprehensive institutional policy (Leandro; Figuerêdo, 2017). This inefficacy results in the responsibility for addressing, mediating, and making decisions about plagiarism being delegated to facilitators and mediators. Consequently, the lack of assertive and informative discussion on plagiarism ultimately penalizes the student.

Quantitative Analysis of Open-Ended and Close-Ended Questions

In response to the first question, 84% of respondents indicated that they understood what plagiarism is, while 11% were unsure, and 5% were unaware. Question 2 asked students to identify which of several situations constituted plagiarism. Since all options represented different forms of plagiarism, it was expected that students would select all alternatives. The most frequently selected option was Copying verbatim a text or fragment of a text for your work without citation and without including it in the reference list, with 574 responses. Notably, 25% of students selected only this option. Only 287 people selected the all alternatives option, and nine correctly identified all forms of plagiarism, even without selecting the all alternatives option. Therefore, 36% of respondents demonstrated a comprehensive understanding of plagiarism and academic writing conventions. These findings suggest that many students may mistakenly view certain inappropriate academic writing practices as acceptable (Ryan et al., 2009; Lima, 2019; Seitenfus et al., 2019).

Regarding the classification of plagiarism as a crime under Brazilian law (question 3), 87% of respondents indicated awareness of this fact, while 13% were unaware. When confronted with the definition of plagiarism adopted by the University (question 4), 89% asserted that they did not believe they had committed plagiarism or copied content in their academic work. Similarly, Question 5 revealed that 89% of students reported that evaluators had never indicated the presence of plagiarism or copying in their activities.

Although only 91 students reported that plagiarism had been identified in their work (question 5), approximately 200 responded to questions 6, 7, and 8, which were directed exclusively at students who answered yes to question 5. This disparity, when compared with the results from Question 2, suggests that while students may be aware of institutional guidelines or policies on plagiarism, they often do not fully understand their content (Ryan et al., 2009). Seitenfus et al. (2019) observed a similar contradiction—most students claimed not to have committed plagiarism, yet many teachers reported detecting plagiarism in student work either occasionally or frequently. Among those students who had plagiarism detected in their work, the majority indicated that evaluators did not provide clear reasons for why their work was considered plagiarized or copied (62%) and did not offer guidance on how to correct it (64%). In question 8, most students (65%) felt they had not committed plagiarism due to a lack of understanding of what constitutes plagiarism, suggesting that they may have committed plagiarism for other reasons. Furthermore, in question 9, most students (88%) believed it is possible to develop academic work without committing any form of plagiarism or copying.

Table 1 summarizes the responses to question 10, which aimed to assess the importance students attributed to factors identified in the literature (Comas-Forgas; Sureda-Negre, 2010) as causes of plagiarism. The following factors were considered highly important by more than half of the students: procrastination, disorganization and poor time management, and lack of motivation and interest. Among factors related to the skills needed to complete academic tasks, the ease of finding content on the internet and a lack of skills in producing academic work were rated as having the highest importance. These findings are consistent with those of Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010), who identified lack of time, poor organization and time management, excessive assignments, ease of obtaining information on the internet, and lack of skills for academic tasks as the most relevant factors according to Spanish university students.

Regarding factors related to instructors and classmates, most students identified the lack of clear instructions on tasks as a highly relevant factor. Additionally, students underscored the importance of feedback from evaluators, which plays a crucial role in determining whether plagiarism persists as a behavior or is corrected and addressed (Santos, 2015).

Table 1 Percentage of students who attributed high, medium, or low relevance to factors identified as causes of plagiarism in the literature

| CAUSES OF PLAGIARISM | RELEVANCE (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors associated with organization and motivation for studies | High | Medium | Low | Don’t Know |

| The habit of doing tasks at the last minute | 54.5 | 20.5 | 18.5 | 6.5 |

| Disorganization and poor time management | 52.3 | 22.6 | 17.7 | 7.5 |

| Lack of motivation or interest | 50.6 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 7.5 |

| Excessive number of tasks from various courses assigned simultaneously | 49.1 | 24.0 | 18.9 | 8.0 |

| Lack of time to complete tasks | 47.4 | 27.7 | 16.6 | 8.3 |

| The task has a short deadline for preparation and submission | 36.2 | 30.8 | 24.4 | 8.6 |

| Factors associated with the skills necessary to complete the task | High | Medium | Low | Don’t Know |

| Ease of finding information on the Internet | 46.5 | 29.3 | 16.8 | 7.4 |

| Lack of skill or training to produce academic work | 45.2 | 26.7 | 19.0 | 9.1 |

| The task to be done is too difficult | 34.6 | 37.3 | 18.0 | 10.1 |

| It is easier, simpler, and more comfortable than doing the task yourself | 31.9 | 26.6 | 29.9 | 11.5 |

| A feeling that the task does not contribute to your learning | 30.6 | 26.0 | 33.0 | 10.4 |

| You obtain a higher grade than if you had done the work on your own (lack of confidence in your skills) | 29.4 | 30.3 | 28.7 | 11.5 |

| Factors associated with instructors and classmates | High | Medium | Low | Don’t Know |

| Lack of clear instructions on how to complete the assignment | 38.5 | 24.4 | 26.3 | 10.8 |

| Suspicion that the instructor/evaluator does not thoroughly read tasks during evaluation | 30.4 | 24.2 | 27.9 | 17.5 |

| Other classmates also commit plagiarism | 19.4 | 17.9 | 35.0 | 27.7 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

When evaluating factors associated with academic writing skills and competencies, students were asked which databases they consulted most frequently when preparing academic work (question 11). Google Scholar and Scielo were the most cited sources (40%, 326 responses); however, the Google search engine was mentioned more frequently (294 responses) than the university’s virtual libraries (159 responses). Other reliable resources spontaneously mentioned by students included physical libraries and thesis repositories. Additionally, some students mentioned less conventional resources such as news portals and YouTube, which are not primary sources for scientific work. Barbastefano and De Souza (2008) identified that university students often preferred less reliable sources, such as the Google search engine and Wikipedia. Similarly, Seitenfus et al. (2019) found that 26% of students used reliable sources alongside unreliable ones in their research.

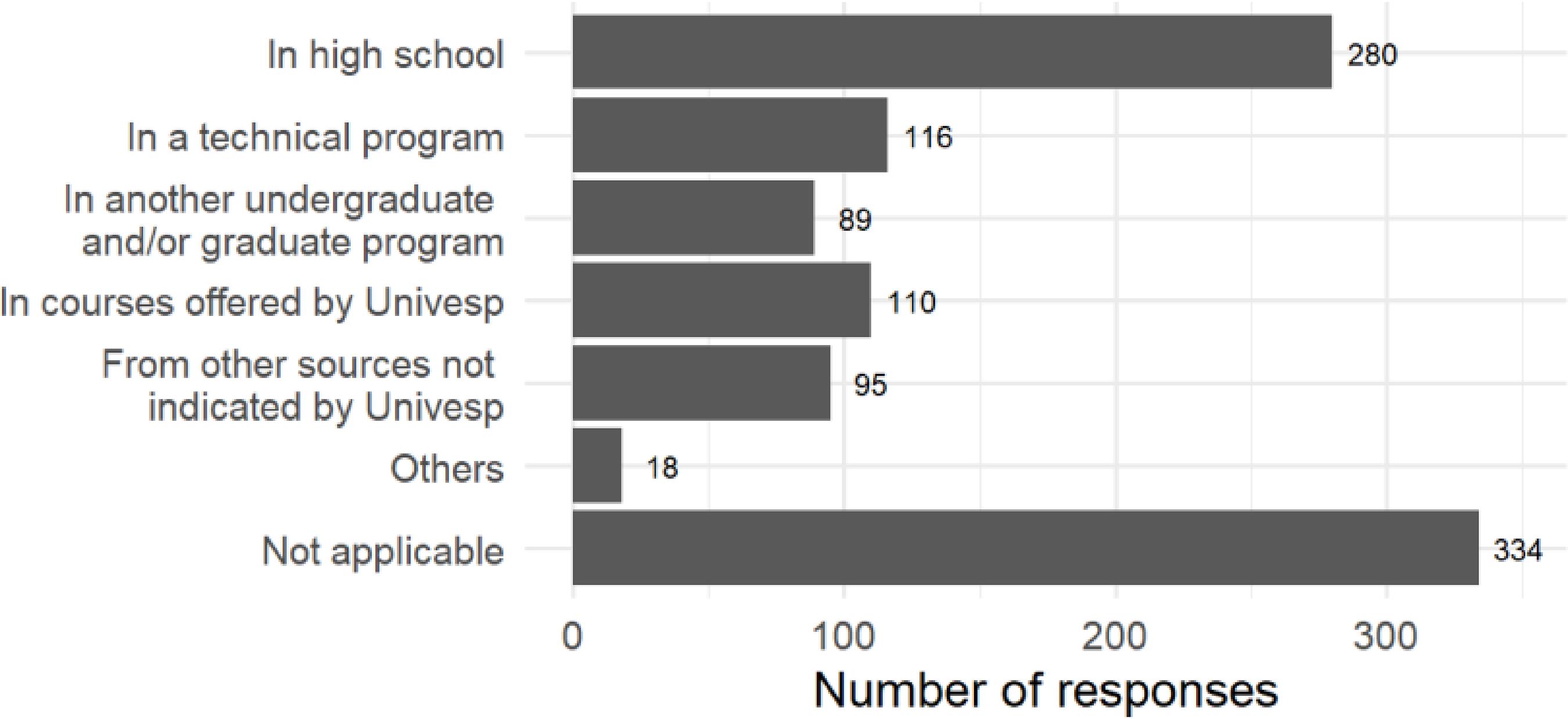

Only 34% of students felt they had the necessary skills and competencies to write their first academic assignment at the university (question 12). In contrast, 27% felt they did not have these skills, and 40% felt they had them only partially. This indicates that more than half of new students lack the full range of skills required to produce academic work according to the University's standards. Among those who reported having some level of skill and competence (question 12), most stated they developed them in other undergraduate or graduate programs, while only 110 cited the courses offered by the University as a source of their academic writing skills (Figure 1).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 Responses to question 13 “[...] where did you acquire these skills and competencies?” directed at students who indicated they possessed the necessary skills and competencies to write an academic assignment when it was first requested by Univesp

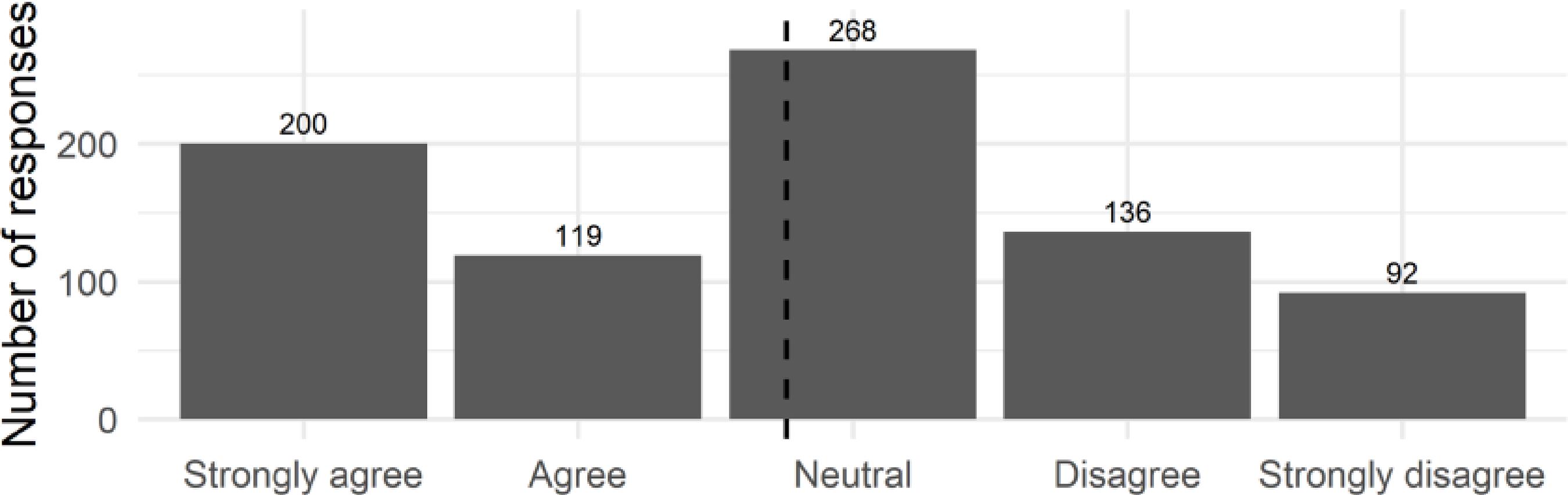

When evaluating whether the institution offers courses with sufficient content and guidance for developing the necessary skills and competencies (question 14), 39% agreed either strongly or partially with this statement, while 33% disagreed either strongly or partially. A significant proportion of students chose not to take a definitive stance, selecting the neutral option (Figure 2).

Note: The average (2.76) is represented by the dashed line. Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 Responses to question 14: “Univesp offers courses with sufficient content and guidance for the development of the skills and competencies necessary for academic writing. To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement?”

When asked if they felt confident and capable of reading and interpreting academic texts, relating them to each other and their research, and producing an original academic text in their own words (question 15), the responses were varied: 46% of students felt confident, while 45% felt only partially capable, and 9% felt they were not capable at all. These findings suggest that a significant number of students have not yet fully developed the skills and competencies required to meet the University’s standards for academic work. This underscores the persistent challenge of mastering academic writing throughout the undergraduate program (Ryan et al., 2009).

Among the most effective measures to combat plagiarism (question 16), most students (489 responses) emphasized the need for a plagiarism detection tool to be used before submitting assignments. In 2021, the University introduced SafeAssign, a system for detecting plagiarism within submissions through the Virtual Learning Environment (AVA), which may address this demand. The second most frequently selected option was the inclusion of additional resources on academic writing and plagiarism in the AVA (417 responses). This suggests that students have recognized a lack of adequate attention to plagiarism within regular courses, as discussed earlier. Other spontaneous responses included better guidance from facilitators and mediators, improved orientation on the topic within existing courses, and the introduction of optional courses focused on academic writing and plagiarism. These responses reflect a call for a more thorough educational approach to plagiarism (Adam; Anderson; Spronken-Smith, 2017), which requires shared responsibility among students, staff, and the institution (Selwyn, 2008).

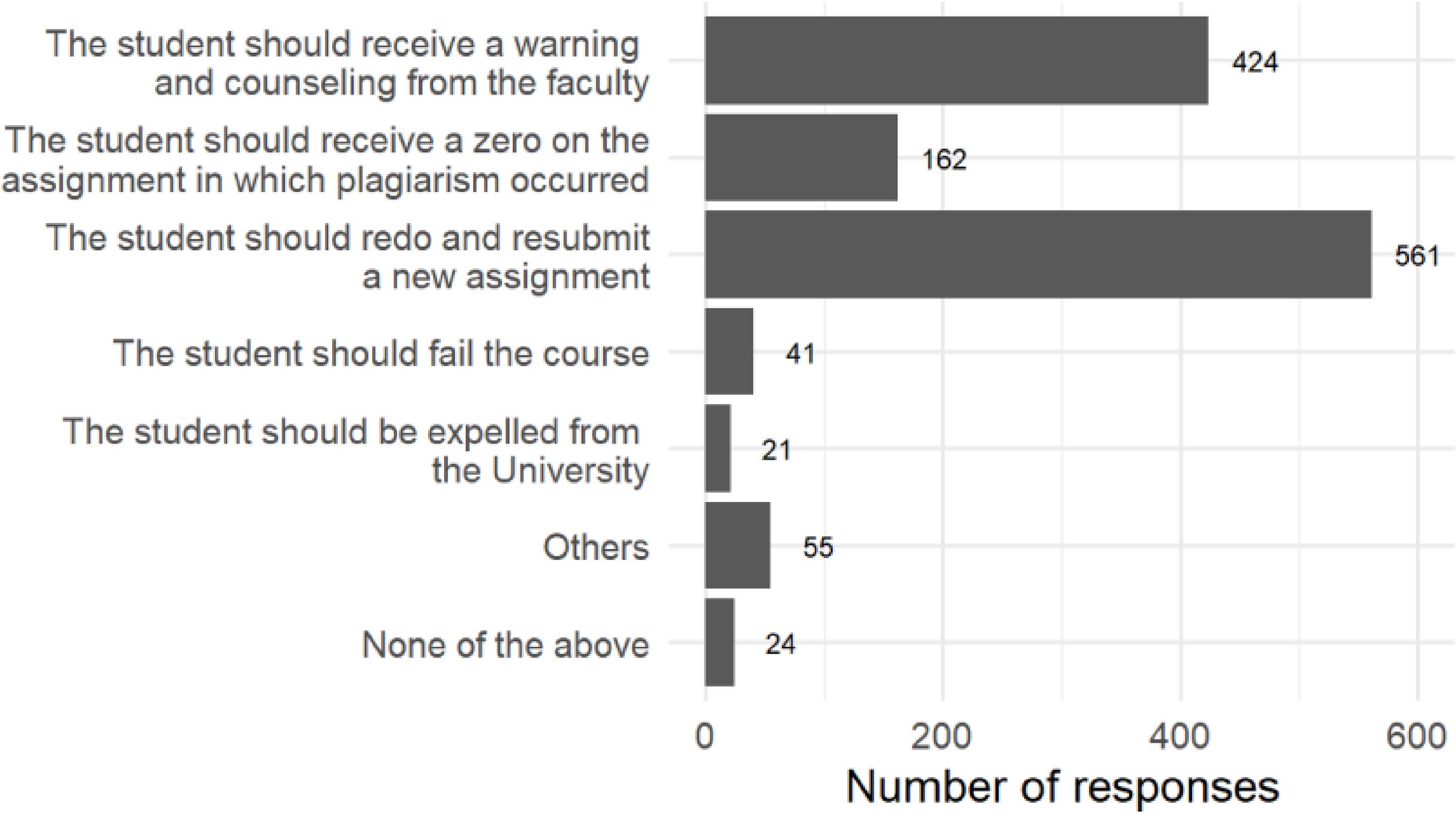

Concerning possible penalties for plagiarism (question 17), most students preferred a more lenient approach, favoring warnings and counseling from faculty, along with the opportunity to resubmit the plagiarized work (Figure 3). Few students supported more severe penalties, such as failing the course or expulsion. Some suggested a gradual penalty approach: issuing warnings and guidance for new students while imposing stricter penalties for repeated offenses or plagiarism in the TCC. Others recommended that penalties should be proportionate to the severity of the plagiarism detected. Similarly, Lima (2019) found that students favored dialogue, the opportunity to revise and resubmit work, and invalidation of the plagiarized activity, with fewer endorsing harsher measures like criminal charges or failure. Therefore, students emphasized the need for constructive feedback from the pedagogical team to improve their academic work without facing severe penalties (Adam; Anderson; Spronken-Smith, 2017). This approach is also preferred by professors, who generally advocate for penalizing only in instances of repeated offenses and following the severity of the plagiarism (Gomes; Menezes, 2022).

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Figure 3 Responses to question 17: “Regarding penalties for plagiarism, which do you believe Univesp should adopt?”

Given that 87% of students acknowledged that plagiarism is considered a crime (question 3), it is surprising that the majority favor lenient penalties or no penalties at all. This discrepancy likely reflects a fear of severe consequences, such as failing or expulsion. Despite their awareness of the implications of plagiarism, students seem to seek to avoid harsh penalties while continuing to engage in such practices (Sureda, Comas, & Morey, 2009). Even with a full understanding of moral and ethical standards, students continue to commit plagiarism without adequately assessing the potential consequences, hoping to evade any substantial reprimand.

A punitive approach should not be the primary corrective measure; rather, the focus should be on developing students' interpretive and writing skills. When these skills are well-developed, the need for deliberate copying without proper attribution diminishes. According to Santos (2015), when students stop viewing evaluative tasks as punishment and begin seeing them as integral to their learning process, they become more engaged in producing original work. Therefore, university policies should foster sound academic practices rather than focusing solely on imposing penalties, as many students struggle to understand why unintentional plagiarism is deemed dishonest (Adam; Anderson; Spronken-Smith, 2017).

In response to question 18, which explored the factors leading students to commit plagiarism, 22 distinct categories were identified, each receiving at least two mentions (see Supplementary Material). The most frequently cited cause was a lack of knowledge and skills for producing academic texts (278 mentions). Additionally, 143 and 106 students mentioned, respectively, a lack of time for studying and a lack of commitment to the undergraduate program. Other significant reasons included the convenience of copying readily available content from the internet (60 mentions), and inadequate guidance from Univesp (59 mentions), including insufficient course content, materials, and support from facilitators and mediators. Intrinsic factors related to distance education were mentioned only five times. These findings align with observations by Adam, Anderson, and Spronken-Smith (2017), highlighting that students' responses predominantly reflect common themes in the literature — plagiarism as a moral and legal issue, and a consequence of deficiencies in academic writing skills.

In question 19, which asked about the acceptability of plagiarism in academic work, most students (436 mentions) indicated that plagiarism is not acceptable. However, 95 students suggested it might be permissible in specific situations, such as when committed by beginners or unintentionally. Additionally, 83 students argued that plagiarism should be acceptable, although many have confused plagiarism with direct and indirect citations. These responses reveal that many students do not fully understand what constitutes plagiarism, why, and how to avoid it (Adam; Anderson; Spronken-Smith, 2017; Seitenfus et al., 2019). The belief that direct citation is inappropriate underscores this lack of proficiency with academic writing conventions (Ryan et al., 2009).

Analysis of Open-Ended Responses

This section aims to explore and present the nuanced perspectives of students as captured through their open-ended responses. They reflect their freedom and autonomy in crafting their views, highlighting an essential aspect of addressing plagiarism: creativity. We have preserved the responses in their original form, including their style, spelling, and grammar. We selected responses that provided less obvious insights and that could assist in developing strategies to combat plagiarism in ways that are closely related to the practice of scientific work.

Justifications for plagiarism were generally based on reasons such as a lack of time, laziness, fear of making mistakes, and lack of information. These factors will be explored in more detail below. Concerning penalties, there is widespread agreement that warnings and grade reductions are necessary. The more closely the concept of plagiarism aligns with common sense, the more it is understood as a crime. The relationship with punishment arises from this perception, even in cases of contradiction — when the student claims to be unaware of what plagiarism is, but still acknowledges the need for punishment. This reflects a sense of anguish — not knowing about the subject, but fully understanding it through its consequence: the crime.

It is important to recognize two common influences reflected in student responses, which suggest a background shaped by experiences in either public or private schools — the punitive culture and a limited understanding of scientific research. These factors contribute to a significant gap that students encounter when transitioning from basic education to university, particularly in their struggle with academic writing. This gap is a consequence of the lack of a research-oriented learning culture in basic education. Many university students frequently report past experiences of being encouraged to copy content from the internet for their assignments (Barbastefano; De Souza, 2008). As a result, they arrive at university with the misconception that research involves compiling and reproducing fragments from other texts (De Lima; Souto Maior, 2019).

Response 123 reflects this issue: “the method we were taught in the past: copying from the blackboard, memorizing the multiplication table. It did not prepare us to believe that we are capable of writing our academic assignments.” This highlights the need to provide students the confidence and autonomy to view themselves as knowledge-producing subjects. Contact with scientific inquiry and critical thinking, which provides students with the confidence to have a voice2, often surprises students in their initial university experience. This shock experience can be unsettling, as it questions established habits from prior schooling, without clarifying the role of science and how to engage with existing knowledge.

These issues reflect a limited understanding of the reconstructive role of science (Demo, 2011a) and of originality that is not tied to strict purism. Specifically, students frequently interpret others' words unilaterally — failing to recognize the role of dialogue among multiple authors in contextualizing information within academic work. Consequently, students often lack an understanding of originality in writing as the ability to recreate meaning through intertextuality — connecting their ideas with existing knowledge and using synthesis to achieve this (Pinto, 2016).

Many issues can be traced to a minimal understanding of scientific work, as evidenced by responses reflecting insecurity, such as: “[...] the fear of making mistakes is greater.” (Response 44). This raises a fundamental question: science is also built on mistakes. What concept of science does this student hold? Viewing academic work as merely a matter of right or wrong misunderstands the scientific and critical nature of university education. It also highlights the lingering influence of a traditional educational approach that emphasizes finding the correct answer. Students often enter university expecting a reproduction of their basic education experience, characterized as a sequence of “[...] listening, copying, reproducing, and taking exams.” (Demo, 2011b, p. 55). It is no coincidence that the feeling of school being out of context with its time reveals symptoms, strongly observed today, that even inhabit common sense. Response 159 illustrates the confusion between school activities and research, particularly regarding the concept of plagiarism: “[...] plagiarism as copying should not be accepted, but when it comes to a work for which we did not conduct the research, obviously everything that is written is based on other works.” But plagiarism is copying, after all, relying on others' work is inherent to academic writing and there are formal guidelines for proper citation.

Some responses attribute plagiarism to laziness, a factor previously identified as a major cause among university students in Portugal (Ramos; Morais, 2021) and Brazil (Gomes; Menezes, 2022). However, this issue involves more than just a lack of motivation. It also includes a lack of confidence, with some students using plagiarism as a strategy to mask their demotivation. Their statements reveal not only laziness but also a reluctance to develop an authorial voice. This apathy toward engaging critically with sources can lead to an identity crisis as an author and, ultimately, to plagiarism (Pittam et al., 2009). The emphasis on obtaining a degree or passing a course, rather than genuine learning, reflects a bureaucratic approach to education, and this mindset impacts scientific work and the perceived value of science.

In this context, Response 37 is particularly intriguing: “The fact that it is virtual. at distance.” It suggests that the virtual nature of distance education might lead to a sense of ease or complacency and possibly a diminished respect for non-face-to-face education. This sentiment is echoed in other responses that reflect a peripheral engagement with the university, for example: Response 7: “[...] lack of time [...]”; Response 20: “Lack of commitment to the program [...]”; Response 58: “Not taking activities seriously [...]”; Response 151: “Insecurity, complacency, and laziness”; Response 64: “[...] in the specific case of Univesp and other distance education programs, the accumulation of activities by students — who balance work, family, and household chores, for example — ends up pushing them to plagiarize texts. [...]”; Response 413: “Distance education, lack of student-teacher contact, lack of student commitment and responsibility, access to facilities that shorten the path.”

Some responses suggest a need for a deeper understanding of both the nature of university education and the specific characteristics of distance education. This includes recognizing how science is conducted through digital methods, communication networks, and various tools, all of which require a methodological approach. The virtual environment can seem less tangible, potentially fostering a sense of anonymity or lawlessness that may make deceptive practices seem more permissible — not coincidentally, phenomena like fake news and post-truth arise from the anonymity of the virtual world. This is reflected in Response 562, which notes: “The feeling that no one will discover that plagiarism was committed.”

Other responses highlight a lack of guidance, as in Response 59: “The lack of a more flexible library to collect citations more easily and relate them to what is being addressed to make the conclusion more effective in individual dissertation writing. [...]”. This reflects a need for students not only to learn but to master internet research, which is not always flexible. Scientific research involves mastering citation norms and work structuring; however, it also relies on individualized practices such as reading, critical interpretation, and elaboration (Demo, 2011b).

The concept of a dissertation reveals the need to grasp academic genres, as it represents a more comprehensive scholarly production that extends beyond the scope of a single course. Response 82 reflects this issue: “In my case, the methodology course was taught in the last semester, which made my entire undergraduate program difficult [...]”. This statement highlights a structural problem related to guidance and the progression of knowledge construction, pointing to a gap that extends back to basic education and its connection with scientific learning.

Response 114 states: “I think if you put the author in the references it should be accepted, because it is very difficult to write something different if all the texts you read are the same.” Similar texts are important for theoretical grounding and clarifying study paths. However, the idea of writing differently should be thought of as a means of guiding students. Writing differently should not be confused with writing critically; rather, it should be seen as a method to address plagiarism as a mechanical modification of existing content.

In this context, none of the collected responses reflect an understanding of the student as an active participant who engages with texts by relating them to other authors in line with their own objectives and critical intentions. In other words, there is a lack of recognition that reading is an interactive process involving the integration of information from various sources to achieve cohesion and coherence in one's own writing. It is important to clarify that while this approach does not guarantee complete originality — since scientific work is inherently reconstructive (Demo, 2011a) — it should be an integral part of the guidance provided to students.

Response 176 shows a semantic confusion about plagiarism: “The Author does not own the thought, idea, or words. Copying is different from similarity. Caution is needed when considering plagiarism to be an identical sentence or a paragraph with a similar conclusion; this is not the same as an extensive verbatim copy of a significant portion of the work”.

What could be understood by an identical sentence? This perception reveals a confusion between meaning and form, suggesting a lack of confidence in addressing the subject and a need for clearer guidance. To address this, reading exercises should position students as active participants in engaging with texts, and paraphrasing could be employed to consolidate the literature survey. Establishing similarity based on a solid theoretical foundation will help distinguish between indirect citation and mere coincidence. In Response 751, there is a tendency to express ideas through close, nearly one-sided interaction with another's words: “[...] There are some ways of talking about a subject that make it almost impossible not to use the same phrase if you agree with that opinion. In my opinion, the person must cite the source in the work, but not necessarily that the entire work is a copy.” Agreeing with an opinion does not necessarily lead to similar sentences, as one can agree within the scope of the research. Students must be aware of their text as a way to engage with and build upon another's work. Response 657 highlights the urgency for strategies to effectively engage with another's text: “[...] students often do not have adequate teaching about the rules or a deep understanding of the subject studied to create ramifications from it. [...]” What are the strategies for learning to create these ramifications? Response 268 points to this deficiency: “[...] people sometimes read articles and use them as a source but with their own writing.” This evidences the need for a strategy that encompasses the student's relationship with their own voice and guidelines of their text, as in Response 293: “[...] because it becomes almost impossible to develop a work without citing another.”

Response 278 reveals a student’s conception of science: “[...] Today, everything has already been done, and as the saying goes, nothing is created, everything is copied.” This viewpoint reflects a culture of knowledge exhaustion and media-driven stereotypes, suggesting that science is perceived as detached from everyday life and shrouded in mystique (Demo, 2011b). In this context, understanding and questioning what constitutes originality is crucial. Science is a constructive field characterized by ongoing inquiry, and thus, is inexhaustible. The perception of knowledge as limited suggests the need to discuss the historical context of knowledge and scientific production. Each historical moment and technological advancement assumes new questions and demands. The idea of originality expressed by the student resembles an unattainable purity. Scientific work should be viewed as small, incremental contributions to collective knowledge, which involves engaging with and building upon others' ideas. As Demo (2011a, p. 32) elucidates, “[...] the originality expected is not that of a work of art, absolutely irreproducible, but rather that of personal touch, of personal digestion, of specific elaboration; knowledge is not just anything, nor is it something unattainable.”

Science is a collaborative and evolving endeavor shaped by diverse historical contexts. Response 597 reflects the same perspective present in Response 278: “[...] We live in an era where almost everything has already been said or done and it is becoming increasingly impossible to create any content that is 100% original.” This perception is influenced by a common misunderstanding of scientific research, which is often portrayed in the media as groundbreaking discoveries such as those recognized by the Nobel Prize. The news overlooks the extensive effort involved in research, including the ongoing dialogue with similar texts, which would demystify the idea of significant discoveries isolated from everything else. This concept about originality is further reflected in Response 31: “With each passing day (with the increase in the number of students in all academic fields), it becomes more difficult to develop entirely original ideas.”

The conditions set by the institution often make the academic production experience feel rushed, as Response 24 highlights: “because we have a lot of texts to read, pi, tcc and internships all together, people do what they can and not how it should be done.” The overwhelming workload undermines the time available for research, shifting the focus from quality to quantity. While the TCC and PI differ in their time requirements, they share fundamental similarities. The TCC, being a final project that integrates accumulated experience, should be approached as a comprehensive endeavor from the outset, incorporating insights gained from the PI, rather than a standalone task. However, due to distinct terminologies used for the TCC and PI, many students start developing their TCC from scratch, grapple with the fear of self-plagiarism due to difficulties in re-contextualizing their previous work, and are left with just four months to conduct their research. This situation induces anxiety and a disconnect from their broader academic journey. Deadlines and the number of tasks should not overlap, and the TCC should be planned as a culmination of all prior academic efforts, rather than as the result of a few months of research. Moreover, re-contextualizing previous work relies on group consensus, which may not always contribute to the individual academic experience.

Group work is not a problem; indeed, it is a formative differential. However, the time required to complete the assignment sometimes disregards participation that needs to start from scratch due to individual achievements that are sometimes incompatible with collective decisions. This is reflected in the clash of individualities, which shapes the group’s relationship with plagiarism, as illustrated by Response 21: “lack of ability to relate topics to the courses taken, Group leadership that only aims for grades. [...]”. Does opting for plagiarism guarantee a good grade, much like finding the right answer in school or adhering to bureaucratic norms in a company for objective results? We need to reflect on how negative stimuli and past experiences might create a false sense of security compared to making mistakes and developing one's voice. Often, individuals find comfort in group settings where the presence of others' voices can mask their own absence.

Final Considerations

Plagiarism is not explicitly addressed in the University regulations analyzed, which often feature confusing, subjective, or even contradictory guidelines. Additionally, the courses that could support discussions on plagiarism and its consequences fall short of openly and effectively discussing these issues. Students demonstrated a vague understanding of plagiarism; while most claim to know what it entails, fewer than 40% can identify it in all its forms. According to students, the primary causes of plagiarism include poor time management, an overload of activities, a lack of writing skills, and unclear instructions for producing academic work. Other notable factors include a lack of interest, the ease of finding information online, and the pseudo-anonymity of the virtual environment.

The characterization of plagiarism within the distance education institution studied closely resembles that found in face-to-face education. This similarity is marked by the absence of clear policies on plagiarism, a preference among students for proactive rather than punitive measures; and common causes of plagiarism such as lack of writing skills, laziness, convenience, and poor time management. Few students associated their motivation for plagiarism with aspects intrinsic to distance education. Conversely, the lack of time for studying — a challenge students associated with distance education — was frequently cited as a significant factor contributing to plagiarism.

Plagiarism, beyond being a consequence of inadequate research culture and related deficiencies — such as poor critical reading skills and failure to generate new knowledge—also reflects broader contextual elements within the educational institution. This highlights a gap in comprehensive discussions on plagiarism with students, including its various forms and potential consequences. The university needs to integrate opportunities within the curriculum to encourage students' engagement with academic textual genres. This should encompass activities such as reading, interpretation, note-taking, synthesis, and discussion of ideas throughout their coursework while valuing individualized academic production.

Plagiarism is closely linked to students' feelings of unpreparedness and insecurity, as evident from their responses. This issue becomes more apparent when students propose formative measures to address plagiarism, rather than focusing on punitive approaches. Implementing penalties without proper guidance can exacerbate students' fear of making mistakes and lead them to view plagiarism as a safer alternative to reproducing the correct knowledge. To effectively address plagiarism, the University must incorporate a proactive strategy within its educational practices. This approach should tackle the structural and contextual factors driving students to plagiarize. This proposal is grounded in the principle that fostering a genuine research culture requires equipping students with the tools to express their perspectives. Challenging the notion that anything with a formal appearance is beyond critique is essential. The written word demands original responses, rather than mere replication of existing ideas.

Addressing plagiarism involves recognizing a context where students' relationship with their voice is influenced by experiences that shape their ability to see themselves as knowledge creators. Understanding science as a platform for individuals to express their perspectives, rather than merely absorbing existing information, is crucial to overcoming the marginalization of individuality and promoting active participation. Democracy and science share a common value in this regard. To appropriate someone else's voice is to resign oneself to a position of submission that prevents one from seeing oneself as the author of their own journey.

REFERENCES

A COMUNICAÇÃO científica: rigor e ética em pesquisa. Projetos e Métodos para a Produção do Conhecimento. Univesp, 2021. Videoaula do professor. [ Links ]

A CÓPIA, sem indicar a fonte, é um erro! Projetos e Métodos para a Produção do Conhecimento. Univesp, 2021. Fórum temático. [ Links ]

ADAM, Lee; ANDERSON, Vivienne; SPRONKEN-SMITH, Rachel. ‘It’s not fair’: policy discourses and students’ understandings of plagiarism in a New Zealand university. Higher Education, v. 74, p. 17-32, jul. 2017. [ Links ]

ARAÚJO, Elani Regis de Oliveira. O plágio na pesquisa científica do ensino superior. Revista Conhecimento em Ação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 1, p. 93-107, jan/jun. 2017. [ Links ]

BARBASTEFANO, Rafael Garcia; DE SOUZA, Cristina Gomes. Percepção do conceito de plágio acadêmico entre alunos de engenharia de produção e ações para sua redução. Revista Produção Online, v. 7, n. 4, 2008. [ Links ]

BATISTELA, Rosemeire de Fatima. O plágio numa atividade de um curso a distância. Acta Scientiae, Canoas, v. 15, n. 3, p. 479-506, set./dez. 2013. [ Links ]

BLOMMAERT, Jan. Bourdieu the Ethnographer. The Translator, v. 11, n. 2, p. 219-236, 2005. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.695, de 1º de julho de 2003. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 2003. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2003/l10.695.htm. Acesso em: 14 set 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9610, de 19 de fevereiro de 1998. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, 1998. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9610.htm. Acesso em: 24 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

COMAS-FORGAS, Rubén; SUREDA-NEGRE, Jaume. Academic Plagiarism: Explanatory Factors from Students’ Perspective. Journal of Academic Ethics, Dordrecht, v. 8, n. 3, p. 217–232, set. 2010. [ Links ]

DE LIMA, Antoni Carlos Santos; SOUTO MAIOR, Rita de Cássia. A intermediação sensível e a ética discursiva no processo de letramento acadêmico em contexto de educação à distância. Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da Universidade de Passo Fundo, v. 16, n. 3, p. 598-618, set./dez. 2020. [ Links ]

DEMO, Pedro. Educar pela pesquisa. 9ª ed. Campinas, SP: Autores Associados, 2011a. 148 p. [ Links ]

DEMO, Pedro. Pesquisa: princípio científico e educativo. 14ª ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011b. 124 p. [ Links ]

DINIZ, Debora; TERRA, Ana. Plágio:palavras escondidas. Brasília: Letras Livres, 2014. 196 p. [ Links ]

FAPESP. Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. Código de boas práticas científicas. São Paulo: Fapesp, 2014. Disponível em: https://fapesp.br/acordos/SECOVI/boas_praticas.pdf. Acesso em: 06 dez. 2022. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Danielle Mello; MOURÃO, Luciana. Panorama da Educação a Distância no Ensino Superior brasileiro. Meta: Avaliação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 12, n. 34, p. 247-280, jan./mar. 2020. [ Links ]

GIBBS, Graham. Análise de dados qualitativos. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2009. 198 p. [ Links ]

GOMES, Pedro Henrique de Siqueira Ferreira; MENEZES, João Paulo Cunha de. Percepção do Conceito de Plágio no curso de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade de Brasília. Revista Brasileira de Ensino Superior, Passo Fundo, v. 6, n. 1, p. 55-76, 2022. [ Links ]

HAFSA, Nur-E. Plagiarism: a global phenomenon. Journal of Education and Practice, v. 12, n. 3, p. 53-59, jan. 2021. [ Links ]

INEP. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Assessoria de Comunicação Social. Ensino a distância cresce 474% em uma década. Brasília, 2022. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/censo-da-educacao-superior/ensino-a-distancia-cresce-474-em-uma-decada. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

KROKOSCZ, Marcelo. Autoria e plágio: um guia para estudantes, professores, pesquisadores e editores. São Paulo: Atlas, 2012. [ Links ]

LEANDRO, Michele Gomes; FIGUERÊDO, Rafaella Bastos Silva. Análise do plágio a partir da perspectiva dos alunos de uma instituição privada de ensino superior. In: CASSIMIRO, Márcia; DIÓS-BORGES, Marcelle; ALMEIDA, Renan M. V. R. (Orgs.). Políticas de integridade científica, bioética e biossegurança no século XXI. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora Fi, 2017. p. 71-86. [ Links ]

LIMA, Thais Aparecida de. O plágio acadêmico na percepção de estudantes universitários. São Carlos: UFSCar, 2019. 96 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência da Informação) – Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, 2019. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO de trabalho científico. Projetos e Métodos para a Produção do Conhecimento. Univesp, 2021. Videoaula do professor. [ Links ]

PINTO, Maria da Graça Lisboa Castro. A escrita académica: um jogo de forças entre a geração de ideias e a sua concretização. Signo, Santa Cruz do Sul, v. 41, n. esp, p. 43-71, jan./jun. 2016. [ Links ]

PITTAM, Gail et al. Student beliefs and attitudes about authorial identity in academic writing. Studies in Higher Education, v. 34, n. 2, p. 153-170, 2009. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Madalena; MORAIS, César. As várias faces do plágio entre estudantes do ensino superior: um estudo de caso. Educação e Pesquisa, v. 47, p. e235184, 2021. [ Links ]

RYAN, Greg et al. Undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacy students’ perceptions of plagiarism and academic honesty. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, Virginia, v. 73, n. 6, out. 2009. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Fernando César dos. A concepção de trabalho acadêmico de alunas de um curso de pedagogia à distância: um estudo de caso. São Leopoldo: Unisinos, 2015. 115 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) – Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, RS, 2015. [ Links ]

SEITENFUS, Daniel et al. Percepção de Plágio Acadêmico entre Estudantes e Professores de Cursos de Graduação e Pós-Graduação na Modalidade a Distância. Renote, Porto Alegre, v. 17, n. 1, p. 103–112, jul. 2019. [ Links ]

SELWYN, Neil. ‘Not necessarily a bad thing …’: a study of online plagiarism amongst undergraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, v. 33, n. 5, p. 465-479, set. 2008. [ Links ]

SUREDA, Jaume; COMAS, Rubén; MOREY, Mercè. Las causas del plagio académico entre el alumnado universitario según el profesorado. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, v. 50, p. 197-220, mai. 2009. [ Links ]

UFF. Universidade Federal Fluminense. Comissão de avaliação de casos de autoria. Nem tudo que parece é: entenda o que é plágio. Niterói: UFF, 2010. Disponível em: http://www.noticias.uff.br/arquivos/cartilha-sobre-plagio-academico.pdf. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNESP. Universidade Estadual Paulista. Instituto de Biociências, Campus de Rio Claro. Acesso às coleções de Normas Técnicas. Rio Claro: Unesp, 2020. Disponível em: https://ib.rc.unesp.br/#!/biblioteca/fontes-de-informacao-mapa-da-mina/acesso-a-normas-tecnicas/. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Manual de Normalização de Trabalhos Acadêmicos. São Paulo: Univesp, 2018. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1fX-bEq4jG77bV47tZSQtylbtlkpNl8qo/preview. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Normas Acadêmicas. São Paulo: Univesp, ago. 2019a. Disponível em: https://univesp.br/transparencia/normas-internas. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Reescrita Acadêmica. Recurso Educacional Aberto. São Paulo: Univesp, 2019b. Disponível em: https://apps.univesp.br/repositorio/reescrita-academica/. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Regulamento do Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (TCC). São Paulo: Univesp, abr. 2020. Disponível em: https://univesp.br/transparencia/normas-internas. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Manual para orientadores de TCC. São Paulo: Univesp, 2021a. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Orientações para Alunos do Projeto Integrador. São Paulo: Univesp, jan. 2021b. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Regulamento para o Projeto Integrador. São Paulo: Univesp, fev. 2021c. Disponível em: https://univesp.br/transparencia/normas-internas. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2023. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Univesp - Universidade Virtual do estado de São Paulo. São Paulo: Univesp, 2021d. Disponível em: http://univesp.br/. Acesso em: 05 dez. 2022. [ Links ]

UNIVESP. Universidade Virtual do Estado de São Paulo. Univesp em números - 2021. São Paulo: Univesp, 2021e. Disponível em: https://univesp.br/sites/58f6506869226e9479d38201/assets/629ebf217c1bd15e8f448881/Univesp_em_N_meros_2021.pdf. Acesso em: 05 dez. 2022. [ Links ]

1Some of the questions included were extracted from Ryan et al. (2009), Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010), UFF (2010), Araújo (2017), and Seitenfus et al. (2019).

2Here, the author’s voice is understood as “[...] the capacity to make oneself understood as a situated subject” (Blommaert, 2005, p. 222).

Received: October 30, 2023; Accepted: May 31, 2024

texto en

texto en