Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 20-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469834179

ARTICLE

ACTIVE METHODOLOGIES AND EVALUATIVE PORTFOLIOS: WHAT DO BRAZILIAN STUDIES SAY ABOUT THEIR RELATION

1 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná. Curitiba, PR, Brasil. <ruferrarini1@gmail.com>

2 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná. Curitiba, PR, Brasil. < marildaab@gmail.com>

3 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná. Curitiba, PR, Brasil. < patorres@terra.com.br>

This qualitative research is an integrative systematic review of Brazil's scientific production, considering peer-reviewed articles in the educational field. It aimed to answer the question: what is the relationship between active methodologies and the use of portfolios as an assessment procedure? The objective was to investigate the relationship between theory and practice from a complex view of education. We collected data from the platforms of Capes, Scielo and Redalyc platforms. We initially found 115 articles, after treatment with inclusion and exclusion criteria, we obtained 25 publications for final analysis. We found that active methodologies and portfolios are primarily applied in health education in undergraduate degrees. We identified three central relations: legal, educational and pedagogical. Besides evaluation, the portfolio has a status of teaching-learning method and a reflexive attribute when connected to the problematization methodology. As an innovative perspective of the pedagogical practice, they are based on a concept of education based on the complexity paradigm allied to transformative education.

Keywords: active methodologies; portfolios; learning assessment; active learning; integrative systematic review

Esta pesquisa qualitativa consistiu-se em uma revisão sistemática integrativa das produções científicas no Brasil, considerando artigos revisados por pares, na área educacional. Buscou-se responder à problemática: qual a relação estabelecida entre as metodologias ativas e o uso de portfólios como procedimento avaliativo? Objetivou-se investigar a necessária relação entre teoria e prática a partir de uma visão de complexidade em educação. Coletaram-se os dados nas plataformas da Capes, Scielo e Redalyc. Com 115 artigos iniciais, após tratamento com critérios de inclusão e exclusão, obtiveram-se para análise final 25 publicações. Constatou-se que metodologias ativas e portfólios, em sua maioria, são aplicados na educação em saúde, em cursos de graduação. Foram identificadas três relações principais: relações legais, educacionais e pedagógicas. O portfólio, para além da avaliação, obtém o status de método de ensino e aprendizagem e um atributo reflexivo ao aliar-se à metodologia da problematização. Como uma visão inovadora da prática pedagógica, fundamenta-se na concepção de educação do paradigma da complexidade aliada à educação transformadora.

Palavras-chave: metodologias ativas; portfólios; avaliação da aprendizagem; aprendizagem ativa; revisão sistemática integrativa

Esta investigación cualitativa es una revisión sistemática que integra las producciones científicas en Brasil, considerando artículos revisados por pares, en el área educacional. Se buscó responder a la problemática: ¿cuál es la relación establecida entre las metodologías activas y el uso de portafolios como procedimiento evaluativo? También se buscó como objetivo investigar la necesaria relación entre la teoría y la práctica, a partir de una visión de la complejidad en la educación. Se recolectaron datos en las plataformas de Capes, Scielo y Redalyc. Con 115 artículos iniciales se obtuvieron, para análisis final, 25 publicaciones, después de un tratamiento con criterios de inclusión y exclusión. Se constató que metodologías activas y portafolios, en su mayoría, son aplicados en la educación en salud, en cursos de graduación. Fueron identificadas tres relaciones principales: legales, educativas y pedagógicas. Esas relaciones combinan metodologías de la problemática en el uso del portafolio y más allá de la evaluación asigna al propio portafolio el estatus de método de enseñanza, aprendizaje y evaluación, y el atributo de reflexivo. Como una visión innovadora de la práctica pedagógica, se fundamenta en la concepción de educación del paradigma de la complejidad aliada a la educación transformadora.

Palabras clave: metodologías activas; portafolios; evaluación del aprendizaje; aprendizaje activo; revisión sistemática integrativa

INTRODUCTION

The thematic of learning assessment and teaching methodologies are important issues of discussion in Education. These reflections are revealed at different times, especially to meet the epistemological and methodological conceptions that have been presented throughout history. At this point, they are resumed, with emphasis on the foundations expressed in the paradigm of complexity proposed by Morin (2000, 2001, 2007) and in Freire's transformative education (1992, 1996).

In the last decades, with the proposition of active methodologies, the need to investigate possible ways to carry out procedural, continuous, and formative evaluation has reappeared, pointing out, among other resources, the evaluative portfolio. However, the assessment of learning has been discussed in Brazil for decades, especially at the end of the last century, always with the clear intention of overcoming conservative and excluding models, when classic authors such as Hoffmann (1993, 1998), Vasconcellos (1998, 2000, 2003) and Luckesi (1998). In this direction of the classics, there is the influence of foreign authors, such as Hadji (1994, 2001) and Perrenoud (1999a, 1999b), who advocate the need to use evaluative criteria, self-regulation processes, and the methodological approach by competences.

However, when entering the specific field of the portfolio as an evaluation procedure, classic productions by Villas Boas (2005, 2013) stand out, a pioneer in Brazil on the topic. There is agreement that the use of portfolios as an evaluation procedure is consistent with a view of process evaluation, therefore, cumulative and formative. Thus, the concept of portfolio adopted corresponds to the organization and delivery of a set of significant activities that students develop during the learning process, in a certain period, and submit to continuous formal evaluation, that is, the one that takes place during the process of learning (ALVES, 2003; VILLAS BOAS, 2005; BEHRENS, 2008; MIRANDA, 2017). This conceptualization perspective expands in Scallon (2015) since the competency approach is inserted and portfolios are conceptualized as a “continuous and systematic collection of a variety of data that demonstrate the student's progress to the mastery of a competence judged from a descriptive scale” (SIMON; FORGETTE-GIROUX, 1998 apud SCALLON, 2015, p. 357). These portfolio concepts in an evaluative sense in the teaching and learning process are the focus of this study. The term portfolio is commonly used to characterize a set of documents collected for analysis in research, as a portfolio of products and services for the business area, and as a collection of the best works carried out in the professional areas of art, architecture, design, and engineering, is not considered in this research.

Also, in terms and concepts, with the advancement and use of digital technologies, the portfolio in evaluative learning processes has expanded to webfolio, e-portfolio, electronic portfolio, online and/or digital. In this sense, it only varies the storage space for the students' productions, which becomes digital to the detriment of the physical, maintaining the pedagogical fundamentals of use. However, the digital version increases the potential of the activities that make up the portfolio, in addition to written productions, privileging the diversity of languages and multimedia. They also allow access, updating, and editing at any time and place, more immediate feedback, as well as the possibility of sharing with course colleagues (BUTLER, 2006; MIRANDA, 2017). In this study, only the term portfolio is used, regardless of its form of physical or digital production.

In more recent publications, the theme of active methodologies stands out such as the one proposed by Moran (2018), which values the effective participation of students in the construction of knowledge and the development of competences. The author recommends that students learn at their pace, time, and style, through different procedures of experimentation and sharing, inside and outside the classroom. For that, it is necessary the mediation on inspiring teachers, who also welcome all possibilities of access to the digital world.

Although mostly created in the last century, active methodologies, as attested by Ferrarini, Saheb, and Torres (2019), when constituting the keynote of current research and discussions, occur due to the following aspects: one of them refers to the phenomenon of expansion and the use of digital technologies, which promote reflections on new ways of teaching and learning, and the dissemination of innovative paradigms in education, especially that of complexity, which promote scientific production under new bases for the educational process to take place.

The focus of investigations on these topics needs to go beyond approaching active methodologies only as a didactic procedure with the use or not of digital technologies. Active methodologies reflect the underlying conceptions of the teacher's pedagogical practice, depending on how they are conceptualized. This may imply a new curricular reorganization of the course, didactic approaches, study materials, and the school environment as a whole. This change of conception involves the reconfiguration of the learning assessment process, a new role for the teacher and the student, and the use of the portfolio as an assessment procedure.

In this sense, there is a need to embrace a more innovative concept as an alliance between the contributions of the complexity paradigm and transformative education. Regarding complexity, Morin (2000, 2001, 2007) defends the reconnection of knowledge and the vision of the whole. The transformative education proposed by Freire (1992, 1996) seeks to promote critical reflection, dialogue, and collective vision in educational processes, among other assumptions. This alliance supported the analysis of the publications found in this study.

The research seeks to elucidate the possible relationships that Brazilian researchers have elaborated on in the portfolio as an evaluation procedure with the use of active methodologies. It is understood as necessary to establish these relationships, otherwise, the portfolio, used as an innovation in evaluation, becomes a bunch of activities in still conservative pedagogical practices, which continue to privilege grades - and also the use of active methodologies, without changing the evaluation models that remain traditional, with an emphasis on memorization. Theoretical-practical coherence is essential in pedagogical practices.

Therefore, for the portfolio to constitute beyond a portfolio of activities, its relationship with the innovative paradigms in education is important, which in the perspective of Behrens (2005) are those that deal with pedagogical practices focused on the construction of knowledge by the student. The entire current movement of active methodologies stems from reflections arising from innovative paradigms when associated with digital technologies. According to Ferrarini, Saheb, and Torres (2019), although the best-known active methodologies, such as Project-Based Learning ((PBL or ABP in Portuguese) and Case Studies, which were elaborated in the last century, are revised according to the uses of digital technologies in the teaching and learning processes. According to the authors, the Inverted Classroom and Peer Instruction, to mention the most popular today, are from this century and already have a strong influence on the use of digital technologies, without they would not have happened. However, just because of the use of digital technologies, it is not conceived that the methodologies are active. One of the fundamental elements is the production of knowledge by the students. According to Ferrarini, Saheb, and Torres (2019, p. 25),

The concept of active methodologies [...] is summarized as one that necessarily implies placing learning at the center of the process, in which students are mobilized, internally and externally, to produce knowledge, with activities that enable the development of various and complex cognitive processes, being protagonists of their learning, usually from problems to be solved or themes to be explored, in the interaction with the teacher and with other students.

In this way, we observe a strong relationship between the concept presented by the authors and that of Behrens (2005), as practices typical of innovative paradigms.

As for recent productions on the themes, we only found an integrative literature review focused only on portfolios carried out by Miranda and Zen-Mascarenhas (2018) to characterize Digital Portfolios and which proposed to analyze the formats of portfolios that employ informatics resources in the context of health education, therefore, with a different focus from what is proposed in this research.

This research aimed to answer the question: what is the relationship established between active methodologies and the use of portfolios as an evaluation procedure in scientific research carried out in Brazil? Answering this question, in addition to outlining an overview, albeit partial, of scientific production in Brazil on the topic, it aims to contribute to the advancement of investigations into the themes, as well as to establish the relationship between theory and practice from a view of complexity in education. Methodology and evaluation are woven and experienced together in the pedagogical process.

THE RESEARCH AS A SYSTEMATIC INTEGRATIVE REVIEW - MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this article, a qualitative research methodology was chosen, whose centrality lies in unraveling the meanings that the participating subjects attribute to a phenomenon. This is examined “with the idea that nothing is trivial, that everything has the potential to constitute a clue that allows us to establish a clearer understanding of our object of study” (BOGDAN; BIKLEN, 1994, p. 49). The data are presented descriptively, in which abstractions are elaborated as the data analysis converges to groupings and categories.

A systematic literature review was developed using the methodology of the integrative review. According to Botelho, Cunha, and Macedo (2011), it enables the ability to systematize scientific knowledge, so that the researcher approaches the problem he wants to appreciate through an investigative question, outlining an overview of scientific production. Based on the evidence, it uses the analysis of scientific productions already published on the desired topic. With this, it is possible to know the evolution of the theme over time, outline perspectives and lines of scientific production, as well as to visualize new research opportunities. The integrative review is developed in six stages: identification of the theme and selection of the research question; establishment of inclusion and exclusion criteria; identification of pre-selected and selected studies; categorization of selected studies; analysis and interpretation of results; and presentation of the review/synthesis of knowledge (BOTELHO; CUNHA; MACEDO, 2011).

We used the following descriptors - “AND methodologies (active OR teaching), AND (portfolios OR Portfolios)” - to seek data to answer the problem: what is the relationship established between active methodologies and the use of portfolios as an evaluation procedure in scientific productions carried out in Brazil? The terms webfolio and online portfolio, with and without accentuation (in Portuguese webfólio and portfólio online), did not result in differences in the searches.

For collecting only Brazilian productions, data were searched on the platforms of Capes, Scielo (in the org. and web Science version), and Redalyc. The following selection criteria were adopted: production by Brazilian researchers; peer-reviewed journals, articles only; production language in Portuguese, produced by Brazilians; from the educational area; at any level of education and at any time.

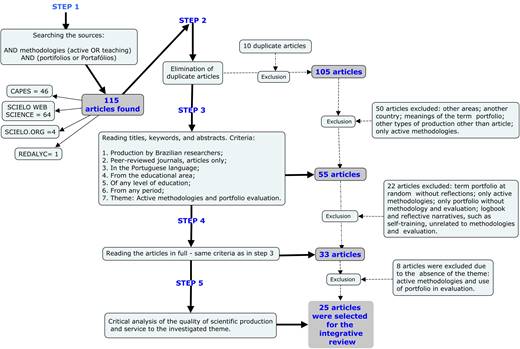

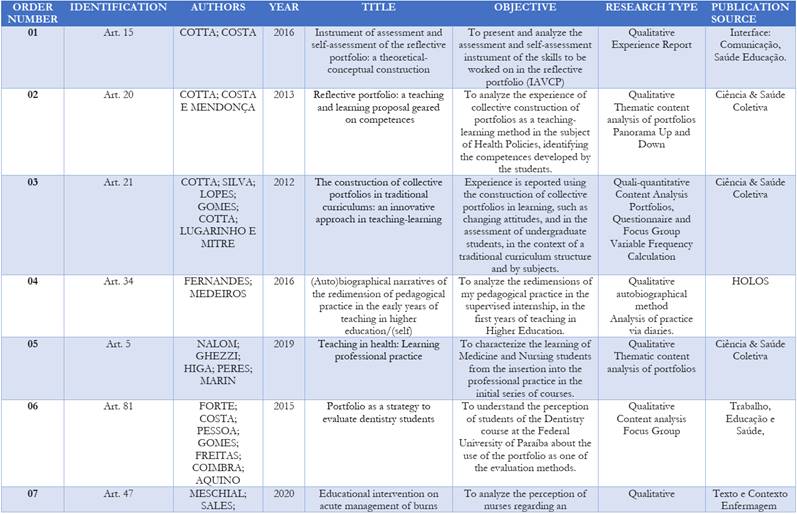

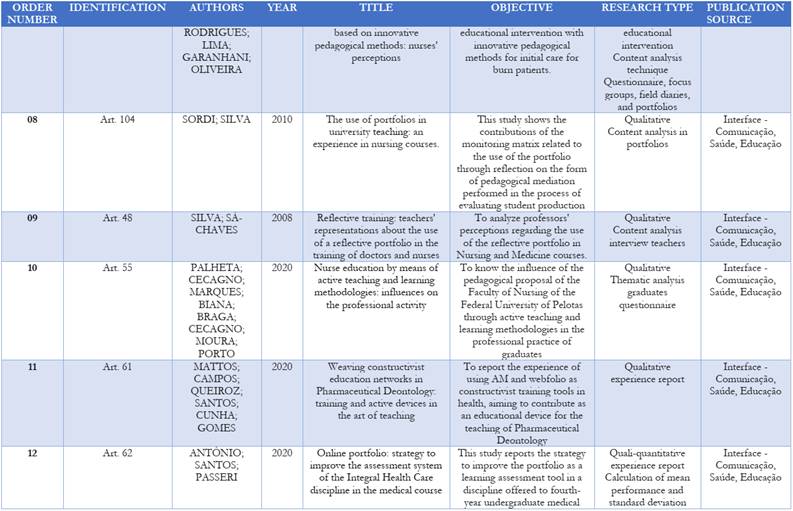

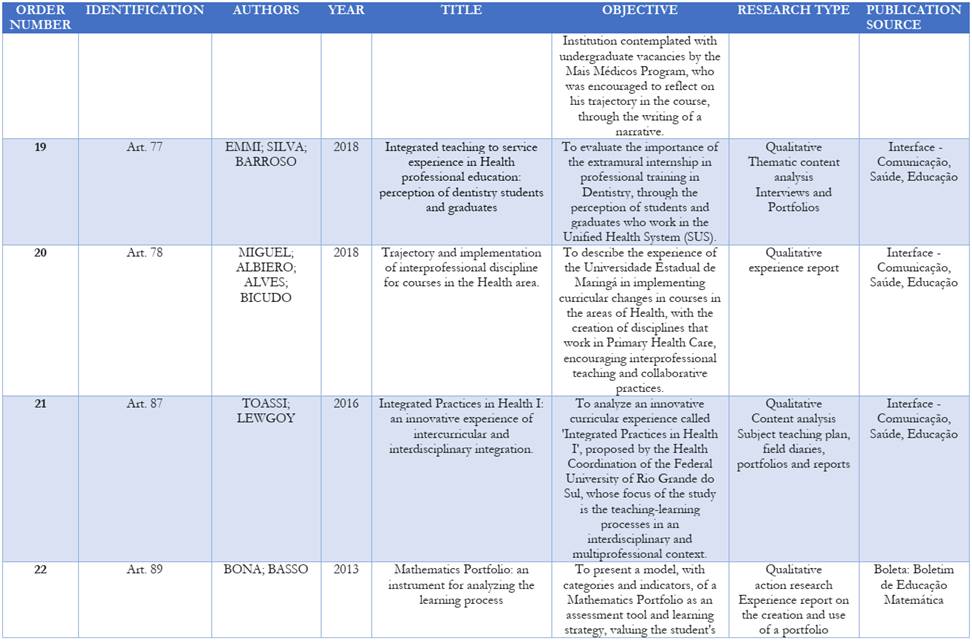

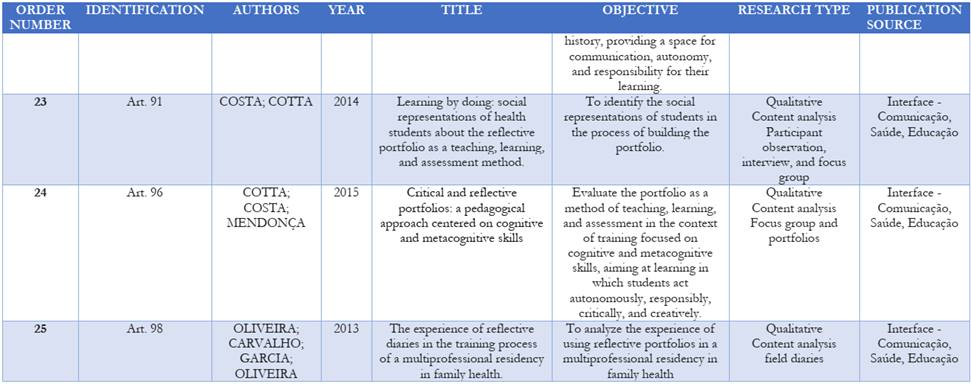

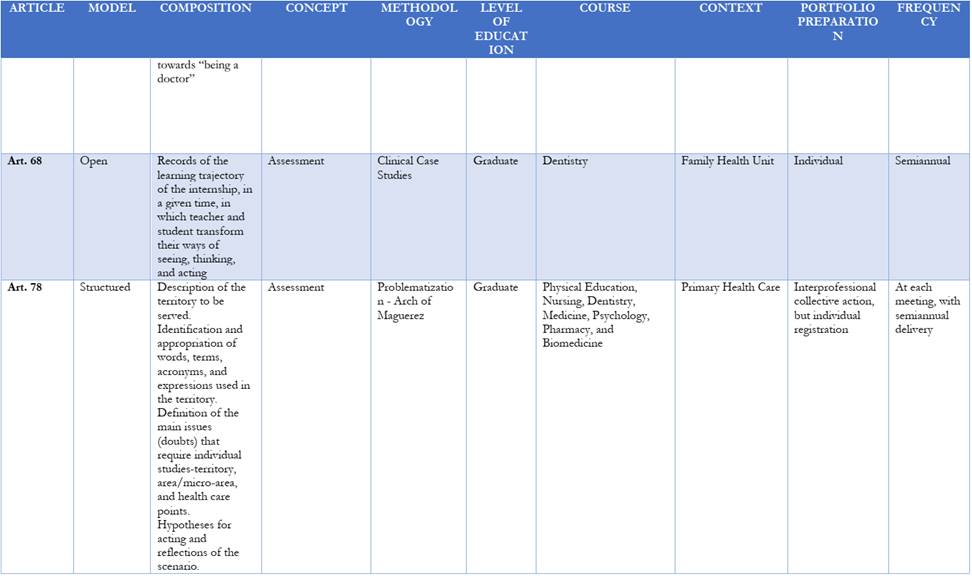

We found 115 articles that went through the inclusion and exclusion process, as shown in Figure 1, resulting in 25 articles selected for the study, which is equivalent to 22% of the initial ones found. The reasons for exclusion refer to articles that addressed the evaluation in evaluation processes of courses, systems, curricular changes, pedagogical proposals, and vision of graduates, without mentioning portfolios. Others dealt only with active methodologies, without an approach to evaluation. Others still attributed different meanings to the term portfolio, other than the evaluation procedure. Only the articles that addressed active methodologies and the use of portfolios were kept, in any part of the document, although in the titles the incidence in the term portfolio prevailed.

Of the 25 articles selected, as detailed in Annex 1, the following were obtained: 17 empirical research articles, four articles of experience reports, and four more articles of experience analysis. These last two typologies were included because, in the verification of the quality of the production, they contained the necessary elements for a scientific article. The integrative systematic review allows the use of different productions, in addition to empirically based articles. In this investigation, we chose only peer-reviewed articles, whether empirically based or not. Thus, other productions were not incorporated.

Data analysis followed the coding methods proposed by Saldaña (2013), using the Atlas.ti software. The 25 articles were included in the software carrying the initial nomination of the list of the 115 selected studies and in order by searched basis. Therefore, the documents analyzed are identified as: Art. 15; Art. 20; Art. 5; Art. 104, etc., for example, although Atlas.ti has recorded the ascending order for the documents. The nomenclature remained and is used.

Adopting Saldaña (2013), the data analysis took place in three cycles: the 1st, the intermediate, and the 2nd cycle. In the 1st cycle, structural coding was used to analyze the composition and quality of the research, identifying the basic elements that should contain, such as the research objective, methodology, and instruments, among others, in addition to the characterization of the context such as areas and levels of education and year of publication.

After this mapping, we followed by exploratory codifications about the contents of the articles, whose codes were created from the problem of this investigation, using active methodologies, portfolio, evaluation, types of evaluation, types of active methodologies, with insertion of other codes that emerged during the skimming of the studies in full. Holistic categorization was used, in which the data for a category can be gathered and examined as a whole before deciding which refinement to carry out (SALDAÑA, 2013).

In the intermediate cycle, the encodings were deepened, creating what Saldaña (2013) calls eclectic encoding. Subcodes were developed for several initial codings, such as the category “portfolios” received sub coding and ramifications resulting from these, such as “concepts” (evaluation, methodology, learning strategy, etc.), “composition” (open or structured), “elaboration” (individual or collective), “assessment concept” (formative, summative, by competences, etc.). In this cycle, we sought to refine the data collected to establish relationships, look for patterns, and group codes into categories, in addition to visualizing paths.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

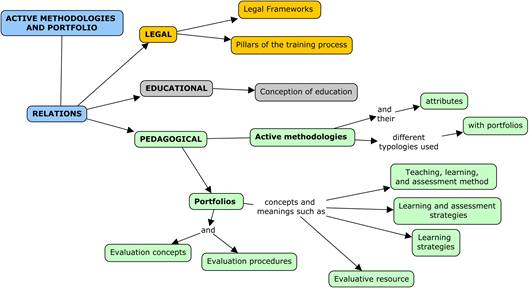

As a first result of the mapping carried out, when there is a 2nd cycle in which the organization of the coded data is grouped into categories or themes, the aim is to prepare a meta-synthesis. Data thematization was used in axial codes, which describe the properties and dimensions of a category and explore how these categories and subcategories related to each other (SALDAÑA, 2013). The relationships represented in Figure 2 were then established and will be explained below.

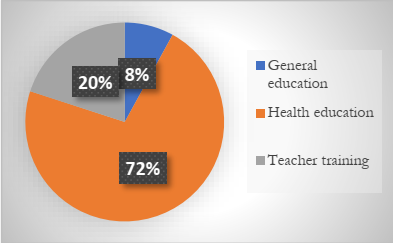

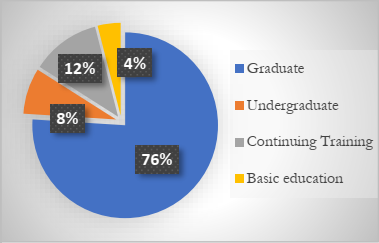

Summarizing the findings about the scientific productions analyzed, we identified that most of the research, 92% of them (23 articles), was qualitative, with only two articles (8%) of a qualitative-quantitative type. Most of the articles, 72% of them, were produced in the context of training health professionals in undergraduate courses. Other publications, 20% of them, were investigations in teacher training courses and tutors also in health education, being three at postgraduate level and two more in continuing education or permanent education, as it is called in the area of health. Finally, two very specific productions were found, 8% of the total: an experience report for the internship discipline in early childhood education of the Pedagogy course and production of basic education, which addressed the portfolio in the mathematics discipline.

Source: The authors (2021).

Figure 3 - Graph on the areas of concentration of scientific productions

Source: The authors (2021).

Figure 4 - Graph on the predominance of scientific productions by level of education

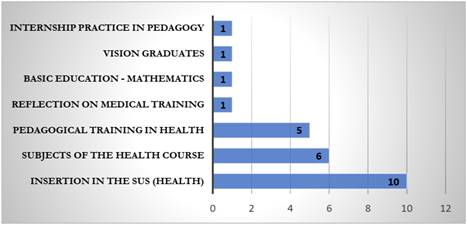

Entering the area of health education, as shown in Figure 5, the predominance of investigations in the area was identified, which involve several courses simultaneously (9), called multidisciplinary or interprofessional teams, followed by Medicine (6) and Nursing (6). There were experiments with up to three courses simultaneously, as well as individual courses.

Source: The authors (2021).

Figure 5 - Courses in the area of health education in which the scientific productions were carried out

In Figure 6, the contexts of use of active methodologies with evaluative portfolios are mostly centered on the insertion of future professionals in the SUS, especially in internships and subjects of Health Care and related ones, but also in theoretical disciplines such as Health Health and Pedagogical Training.

Source: The authors (2021).

Figure 6 - Contexts for the use of active methodologies and evaluative portfolios

These findings are similar to those of an international trend, presented by Butler (2006), who, in a literature review, especially for higher education, identified the expressive use in medical training and nursing courses to develop a system of electronic portfolios. The use happens especially in practical activities of internship and residency, as a tool used to evaluate performance in authentic contexts and also as a “collection of evidence over time that demonstrates achievements in education and practice” (BUTLER, 2006, p. 6). The author also highlighted the use of portfolios for teacher training with the same meaning presented in Villas Boas' experiences (2005), that is, the theoretical-practical reflection in the constitution of the professional identity of the teacher in training. We also show them in the selections carried out in this study, although restricted to the training of health teachers.

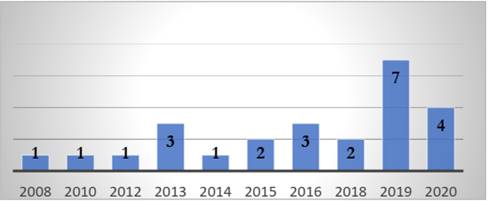

This data is corroborated through the analyzed productions, in which most of them, 68%, were published in the journal called Interface: Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, with a total of 17 articles out of the 25 selected. The journal focuses on productions in the health area. The articles are recent, from 2008, with higher concentrations in 2019 and 2020, as shown in Figure 7.

Although focused on the area of health education and undergraduate courses, the intention is to verify the relationships established between portfolios and active methodologies and to learn from this experience.

Legal relations - guiding frameworks

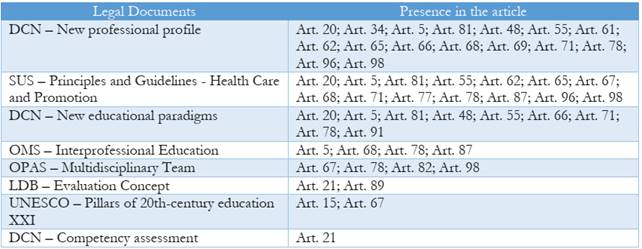

Among the numerous justifications and arguments for the relationship between active methodologies and the use of portfolios, we found what is called legal frameworks, that is, what educational legislation preaches about training. Box 1 shows the frequency that legal and guidance documents were cited.

Source: The authors, Atlas.ti (2021).

Box 1 - Citations of legal frameworks related to the health area

The National Curriculum Guidelines (DCN) for the area of health education were launched in 2001 and updated in 2014. The formation of the graduate profile, the new concept about health, with a focus on its promotion and not on the disease, proposed by SUS, as well as the need for new educational paradigms to meet these precepts favor the use of active methodologies and portfolios. According to the DCN, graduates of courses in the health area must have generalist, humanist, critical, reflective, ethical, and transformative training, committed to improving the population's quality of life and health. The perspective of collective health is adopted, instead of the individual, and it focuses more on the health of the person than on the disease, therefore, a biopsychosocial view of the individual. Health professionals must provide care at different levels, with a special focus on Primary Health Care (FERREIRA et al., 2019). Corroborating this view, other documents from international representative bodies are cited, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which address the need for comprehensive training, the pillars of education for the 21st century, working in interdisciplinary or interprofessional teams.

Regarding the publication of the Pedagogy course and the internship practice, Art. 34 also addressed the legal bases that have changed in recent years regarding the educational profile and performance of the pedagogue. In basic education, the only mention of normative acts was the concept of evaluation expressed in the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education (LDB), current Law 9394/96.

Legal relations - pillars of the training process

The legal frameworks and guidance documents also outlined the new contours for the health training process, as seen in Box 2.

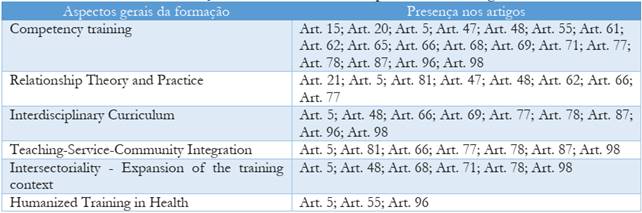

Training based on competences was one of the most cited aspects as it precisely developed the expected graduate profile in the health area, being present in 18 articles. Competency-based training has become the current educational challenge. One can verify the occurrence of the use of classic concepts, which conceptualize competence as the articulation of knowledge and experiences, attitudes, and values to solve complex daily problems, especially those related to the professional context (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 5, Art. 48, Art. 66, Art. 69 and Art. 96). This concept comes from Perrenoud (1999b) or even from Scallon (2015), although Perrenoud has been cited in only two productions (Art. 48 and Art. 69) and Scallon, in none of them. Analyzing the references of the studies, authors were identified who discuss competences in a more particular way for training in higher education and especially for the area of health professionals, as in Lima (2005), Lima et al. (2014), and Blanco (2009), therefore, applied references.

The classic concept of competences is complemented by the active performance of students in contexts of personal and social life, not just professional, given the formative dimension of the health professional's performance, in which knowledge and practices must be for the benefit of the collective, applying the principles of SUS (Art. 20, Art. 5, Art. 96).

As for the dimensions, some mentions highlighted the emphasis beyond cognitive and technical skills, mentioning social or psychosocial, or even relational skills (Art. 15, Art. 65, Art. 68, Art. 87, Art. 78, and Art. 96). The affective and psychomotor domains were also mentioned (Art. 5), as well as the technological and instrumental ones (Art. 15). These indications demonstrate the commitment to the integral formation of the human being and future professional. In this sense, two articles (Art.15 and Art.20) explicitly cited the four fundamental pillars proposed by Unesco (DELORS, 1996) for professional education in the 21st century: learning to be, learning to do, learning to know, and learning to live and work together.

From these findings, it appears that training by competences goes beyond the technicality that was initially understood in the history of Brazilian education and, now, with a view of complexity, it seeks the integral formation of the human being and the professional future in solving problems.

As for the other aspects of training, the DCN is resumed, as previously pointed out, which raised the need to rethink and design new training models, which, in the case of health education, stand out: breaking with decontextualized, fragmented curricula focused on technique, advancing towards interdisciplinary curricula, guided by the transversality of the practice guided by the social determination of the health-disease process. With this, we seek a strong relationship between theory and practice, the integration between teaching-service-community, as well as the expansion of the training context, beyond the academic walls, seeking intersectoriality for humanized, assertive, and proactive training in health. These are the elements that outline the new training of health professionals (FERREIRA et al., 2019). The relationship between theory and practice is also the most cited element in the case of experience in Pedagogy.

Educational relations - conception of education

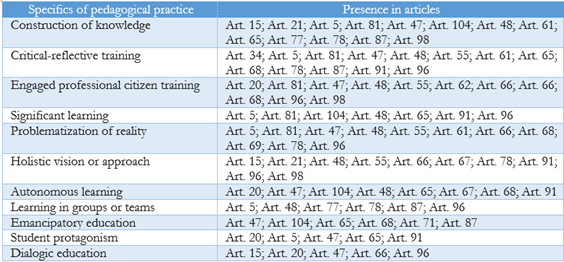

As a result of legal relationships, we identified characteristics of the conception of education, highlighting specificities of the pedagogical practice that meets the expected training.

Certainly, the “construction of knowledge” by the student is one of the fundamental characteristics of innovative paradigms in education, according to Behrens (2005). In this sense, the practices of active methodologies with the use of evaluative portfolios are inscribed in innovative aspects of educational processes, allied to “student protagonism” and “autonomous learning”, which is “in groups or teams”. The knowledge to be developed, resulting from the study and research in different sources and contact with reality, from the existing and the raised problems, requires activities of discussion, reflection, testing, creations, comparisons, syntheses, analysis, transpositions, conclusions, among others organized and provided by the teacher (BEHRENS, 2005).

The expressions “critical-reflexive training”, “engaged citizen and professional training” (in the sense of transforming realities, especially in SUS services), “problematization of reality”, “emancipatory education”, and “dialogical education” are terms endorsed in Paulo Freire. This confirmation was sought through the “text search” feature on Atlas.ti, in all documents, obtaining the following results: of the total of 25 documents, 16 of them, that is, 64% of published research, referred to Paulo Freire. The most used work was Pedagogy of autonomy: necessary knowledge for educational practice, with 13 mentions (Art. 20, Art. 34, Art. 47, Art. 104, Art. 48, Art. 61, Art. 66, Art. 68, Art. 78, Art. 87, Art. 89, Art. 91 and Art. 98); The pedagogy of the oppressed had three mentions (Art. 21, Art. 61 and Art. 71), followed by the works Cultural Action for Liberty and Other Writings (Art. 21) and Extension or Communication (Art. 61), with a mention each. Paulo Freire's Pedagogy is part of the innovative paradigms in education in progressive trends, according to classifications recommended by Behrens (2005). The transformative education proposed by Freire (1992, 1996) points out the need to transform realities in a critical, active, and conscious way, through knowledge built in a dialogical, loving, and sensitive relationship with other human beings. The constructed knowledge is a way of reading and acting in the surrounding reality, which seeks the autonomy of the learning subject.

According to Behrens (2005), the holistic vision or approach also characteristic of innovative paradigms, present in ten articles, is in most cases just mentioned without explanations. However, highlighted quotes refer to the vision of the health education process in which the traditional curricular structure is questioned, and organized into increasingly focused specialties, without considering the vision of the whole and the necessary relationship with social concerns, therefore, with the integration of theory and practice (Art. 21). Evidence was also found that a new educational vision suggests that, when relationships are established between study-service-community, the student starts to interact reciprocally with the context at its different levels and influences it and influenced by it. It is up to the student to discover, maintain or change the characteristics of this context (Art. 48). In this perspective, a view of the whole of reality is sought, in which it is seen as a complex system, with different and multiple facets, sensitive to changes, often chaotic and unpredictable, therefore, non-linear and stable. The whole is formed by the connections and relationships between the parts and the context, the whole being greater than the sum of the parts (Art. 67). Also, the holistic perspective seeks the integral formation of the human being, seeing it in the biological, psychic and social perspectives, integrating reason and emotion, as well as recognizing the importance of values, emotions and preferences that underlie rationalities (Art. 66). The holistic view is characteristic of the complexity paradigm, which seeks to overcome the fragmentation of knowledge, the view of pertinence on what to learn and a global, multidimensional and interdependent view of science, as well as the integral formation of the student in its multiple dimensions and relationship with the context (BEHRENS, 2005; 2008).

As for the meaningful learning mentioned in the nine articles, it refers to the fact that the practice with reflective portfolios stimulates, produces, facilitates, promotes, transforms, and crowns meaningful learning, without making the concept used clear. Only the Arts. 48 and 65 refer to meaningful learning that incorporates new meanings to existing knowledge, generating new learning, through reflection and interaction between peers and contact with reality. This concept is similar to that advocated by Ausubel (1980), although one of the articles referred to Coll (2005). Art. 96 visualizes meaningful learning in terms of the practical application of what future professionals are learning.

Based on the above, the foundations that support the use of active methodologies and portfolios are Paulo Freire's critical-emancipatory conception and Edgar Morin's holistic approach or paradigm of complexity, although he is mentioned only in Arts. 66 and 78 and in Ausubel's significant learning, he is not even mentioned. The foundations of these precepts present a coherent relationship between theory and practice and demonstrate the intertwining of innovative educational perspectives.

Pedagogical relations - attributes of active methodologies

We identified that the scientific productions analyzed did not deal with reflection on the concept and meaning of active methodologies. On the contrary, when they mentioned its use, they did so about the professional profile to be developed, especially the critical-reflective one, and the problematization necessary for understanding and professional performance, with intervention, in reality, establishing relationships between theory and practice (Art. 20, Art. 21, Art. 81 and Art. 67).

However, the construction of knowledge (Art. 5, Art. 48, Art. 66, Art. 66, Art. 71, Art. 87, and Art. 91), the role of students (Art. 104, Art. 20, Art. 47, Art. 68 and Art. 61), interaction (Art. 5 and Art. 55), problem-solving (Art. 20, Art. 21, Art. 81, Art. 104, Art. 61 and Art. 67) were aspects in the productions when mentioning active methodologies, reinforcing what was previously exposed about the concept of education. By understanding active methodologies on this prism, a similarity to that advocated by Ferrarini, Saheb, and Torres (2019) is identified.

On the other hand, there were mentions of buzzwords characteristic of active methodologies, using terms such as “learning by hands-on”, emphasizing “learning by doing” and “learning through action” (Art. 96). Only the specific production of basic education (Art. 89) linked active methodologies to the use of digital technologies and problem-solving.

Therefore, the concept of active methodologies implicit in the productions concerns the centrality of the student in the process of solving problems, building knowledge among peers, acting in reality and changing it, and mobilizing different resources.

Pedagogical relationships - active methodologies combined with the use of portfolios

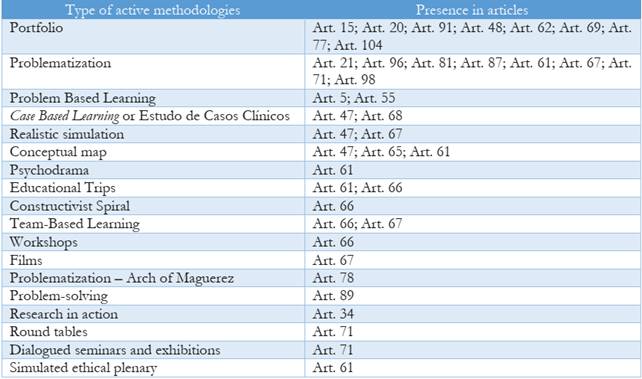

Using in vivo coding, according to Saldaña (2013), all active methodologies presented and used in the analyzed productions can be identified and named. In vivo coding uses the term found in the data.

Source: The authors, Atlas.ti (2021).

Box 4 - Types of active methodologies mentioned in the analyzed productions

An interesting and unexpected finding, present in eight articles, is that the portfolio was nominated and used as an active methodology. This aspect will be explored further in the analyses.

One of the most used active methodologies in the publications was problematization, present in eight articles and named simply that way. This term is typical of progressive trends in education for the formation of a critical and active profile. The well-known ones were also mentioned - problem-based learning and problem-solving (the latter, for basic education), resulting from problematization, but with a bias more towards active methodologies -, as well as those customized for the health area, such as Arch of Maguerez and the constructivist spiral. Research in action, although it addresses problems, refers to scientific research and was used in the experience of the Pedagogy course.

The case study was explicitly mentioned in two articles, although they are clinical cases, and not the concept of case studies generally applied in areas such as Law, Administration, and others. Although not mentioned as methodologies, their presence in the composition of the portfolios was also identified in five articles (Art. 62, Art. 98, Art. 69, Art. 47 and Art. 55) as clinical case studies experienced in internship situations and professional practice.

For the area of health education, terms of specific methodologies or techniques were found, such as realistic simulation (constituting a simulated scenario for the experience of patient care) in Arts. 47 and 67; psychodrama (approaching individual and group conflicts through theater-inspired techniques) in Art. 61; educational trips (artistic educational actions aimed at articulating rationalities and emotions) in Art. 61 and 66; and simulated ethical plenary (problem-situation, which can even be dramatized and which explicitly contains ethical problems to be identified and debated in plenary), present in Art. 61. On the other hand, roundtables, seminars, films, workshops, concept maps, and dialogued exhibitions, found in certain articles, as shown in Box 4, are more active strategies than methodologies.

In addition to the DCN recommending innovative teaching and learning processes, according to Ferreira et al. (2019), health training, especially Medicine, has gone through three generations of educational reforms. According to the authors, the first extended the concept of training for professional practice to hospitals; the third promoted rethinking the meaning of health, especially the concept of collective health by the SUS. The second, object of this reflection, refers precisely to the training models of future professionals, although the authors do not mention a specific time:

The second reform introduced pedagogical innovations, such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), active methodologies, and work in small groups in the training of health professionals. Medical faculties, in particular, were encouraged to break with hierarchical structures and traditional teaching models to adopt student-centered teaching-learning methodologies (FERREIRA, 2019, p. 1).

To form the expected profile, form competences, and develop innovative teaching and learning processes, these methodologies are in line with what is desired.

Pedagogical relations - concepts and meanings attributed to portfolios

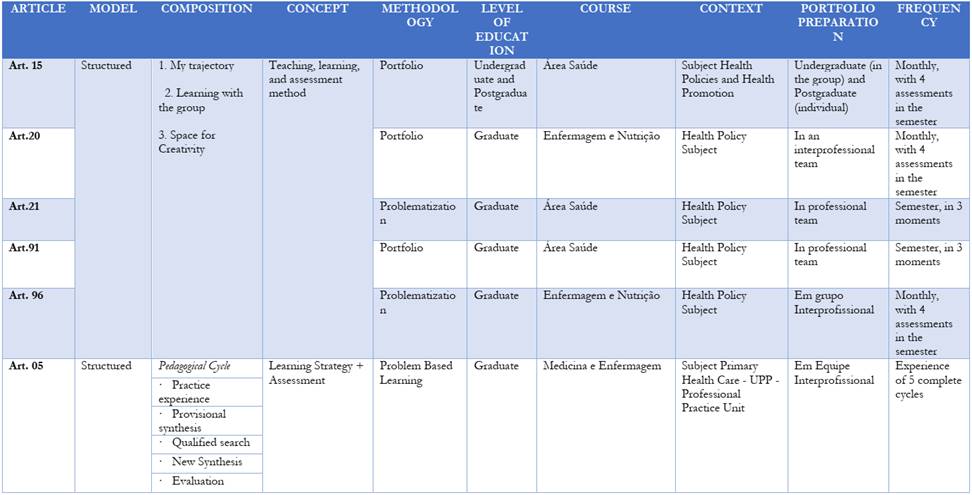

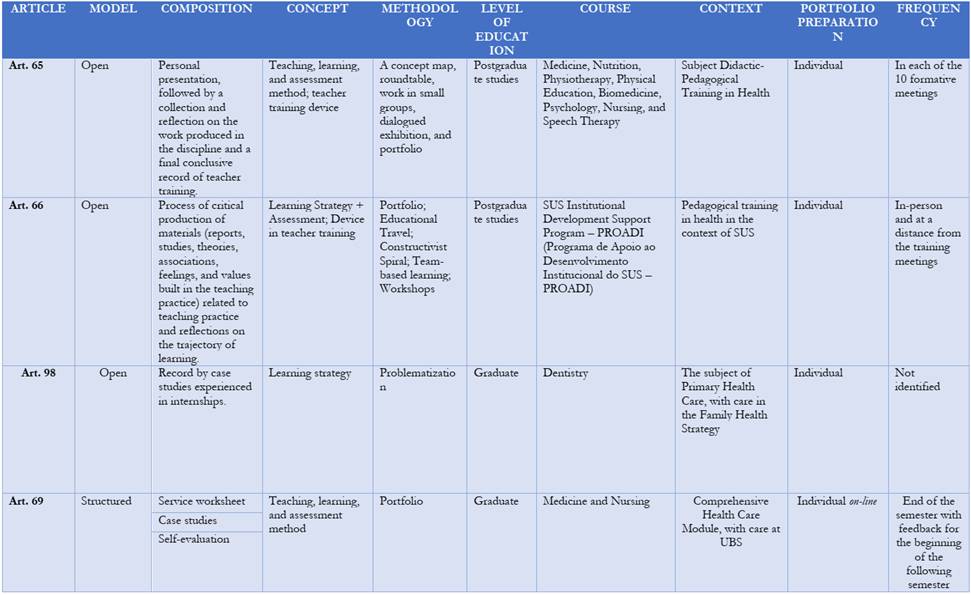

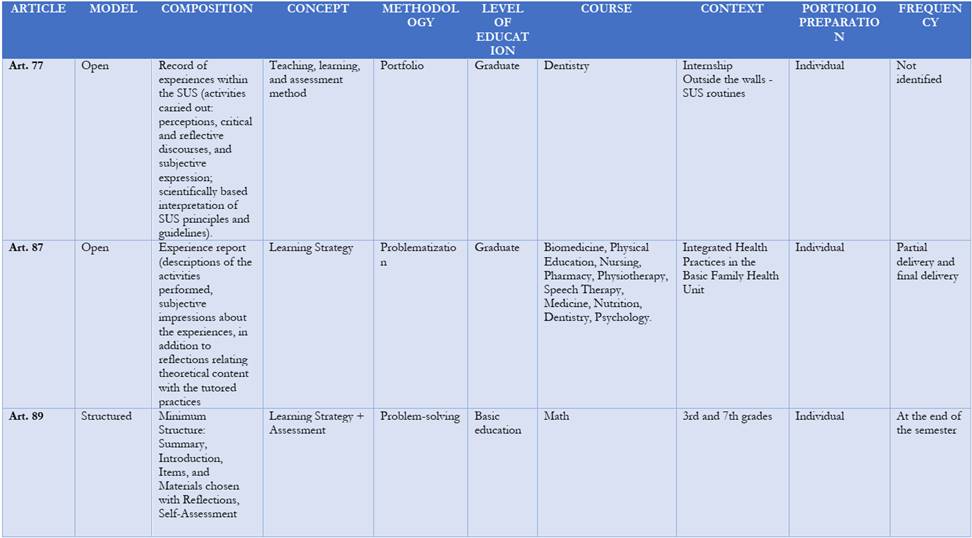

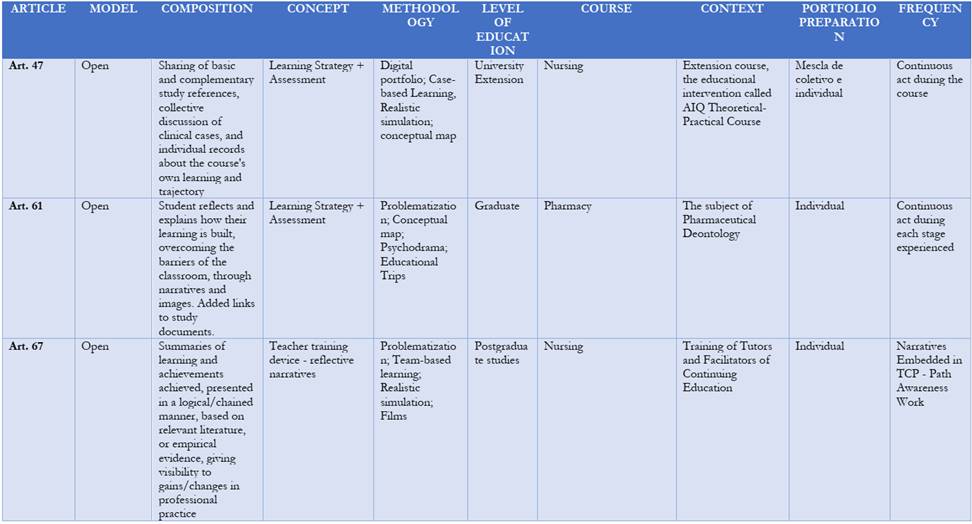

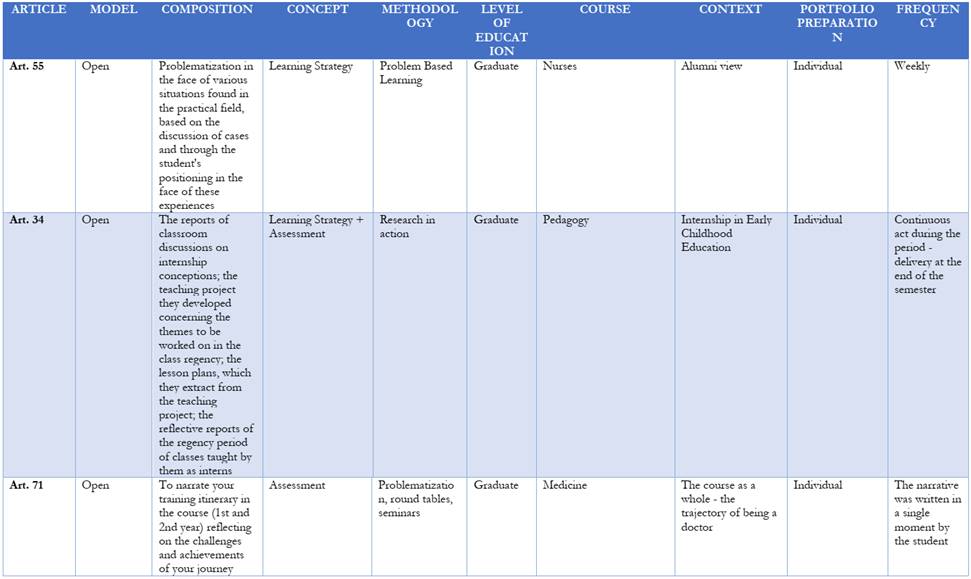

Portfolios have been found to go beyond simply a resource, tool, or assessment procedure. As explained above, it is considered an active methodology, as well as a learning strategy + assessment or simply a learning strategy. We sought to understand these concepts, exploring the composition of the portfolios, in addition to the context of use, a form of elaboration, and periodicity of delivery or analysis. Through the synthesis matrix in Annex 2, some findings can be elaborated; however, some fundamentals are presented first.

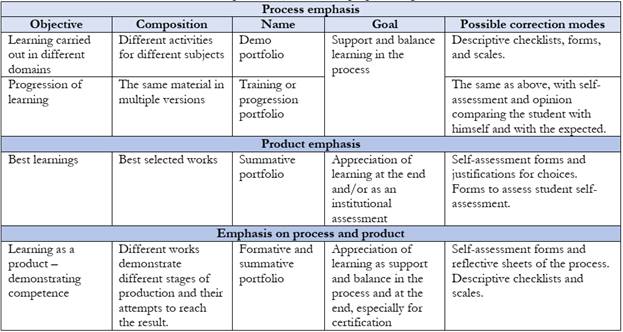

According to existing experiences regarding the composition and delivery of portfolios, it was identified that, according to Behrens (2008), the combinations of what will be part of this composition are carried out at the beginning of the process, via a didactic contract, which can be reviewed at any time. Villas Boas (2005) also suggests building the portfolio in the process. This leads to understanding the portfolio to support learning progressions over time, as exposed by Scallon (2015). However, in Alves (2003) and Miranda (2017), after all the processes are carried out, the student analyses, selects, and chooses will compose his portfolio, showing delivery only at the end of the period. In this case, Scallon (2015) attributes the purpose of certifying the learning carried out by the student, whether partial or final of a course.

By these signs, we identified that the composition of the portfolio can be defined by the teacher a priori and negotiated with the students, defined by the students and selected by them, as well as thought and defined by the school in its evaluation policy (SCALLON, 2015). Thus, the teacher must have a clear objective for using the portfolio, which, according to Scallon (2015), may vary, as shown in Box 5.

Source: The authors, based on Scallon (2015, p. 361-365; 374-382).

Box 5 - Emphasis, objectives, and purposes of portfolios

Although Scallon (2015) mentions these possible differences in composition and purposes of using the portfolio, the author recognizes that, in practice, they often get mixed up and gain the same contours.

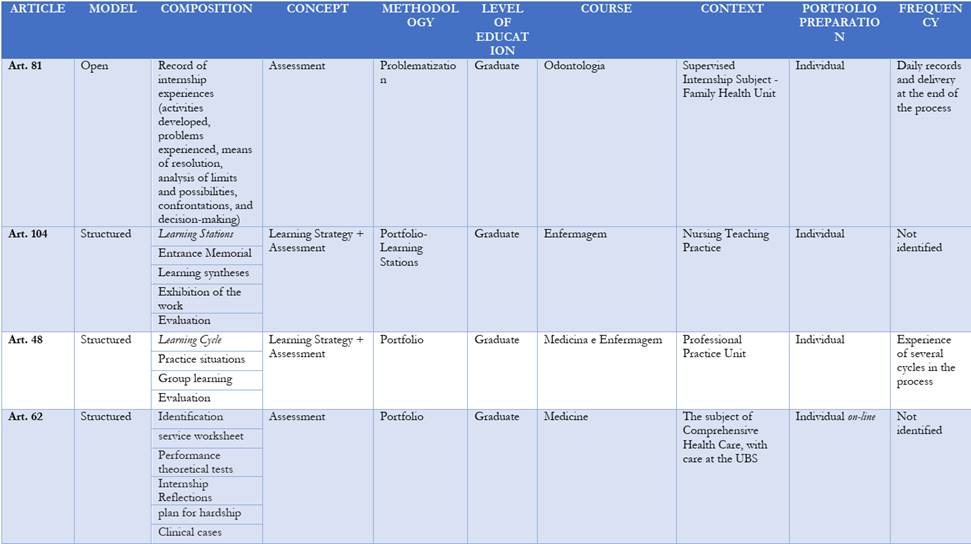

In this investigation, concepts related to structured and open models were elaborated. The structured ones are those that follow a list of items, stages, or phases, to compose the portfolio, in a sequence to be followed with circularity in the process. There were 12 articles in this sense. Examples will be explored next. The open models, identified in 13 articles, are those that only indicate that the portfolio must contain reports, pointing out some elements to consider in writing, usually narrative. For example, Art. 55 requests the recording of actions, tasks, and learning through a narrative discourse about the educational activities experienced in nursing internships. It emphasizes that it seeks to stimulate the creative resolution of the problems experienced, trying to understand the limits, the options for coping, and the difficulties of the action and the issue, subsidizing the decision-making process. Proposed in this way, although with an open composition, it presents a priori evaluation criteria.

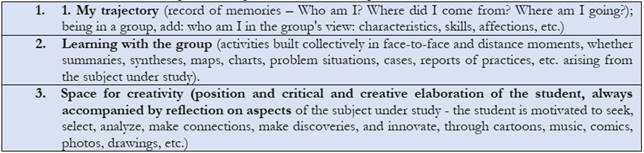

Portfolios as a teaching, learning, and assessment method

One of the important findings refers to the portfolio as an active methodology (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 91, Art. 48, Art. 62, Art. 69, Art. 77, and Art. 104). However, there is no conceptual pattern that highlights this finding. We identified the use in undergraduate and graduate courses, in which the portfolios cover subjects such as Health Policies, but also Professional Practice Units, such as extramural internships and modules or disciplines in which Health Care makes living in the SUS possible. Its structured composition gains strength from the portfolio being mentioned as an active methodology. This was found in seven (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 91, Art. 104, Art. 48, Art. 62, and Art. 69) of the eight studies analyzed. The portfolio as a methodology, in this sense, presents a step-by-step, but cyclical in some stages, giving the movement of learning the discipline or professional practice.

Analyzing more deeply the models of structured portfolios, we identified that the most widespread comprises the composition shown in Box 6. This model was used exclusively in the disciplines of Health Policies and Health Promotion (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 21, Art. 91, and Art. 96), with exclusive moments for the portfolio analysis stops, being from three to four during the semester. They conceptualize the portfolio as a method of teaching, learning, and assessment, which is inferred that corresponds to the structure and development of the discipline, with the 2nd and 3rd topics of the portfolio taking place in cycles. Cotta, professor and author at the Federal University of Viçosa, is one of the authors who references this concept of the portfolio, with learning, focused on training through skills and specificities of the SUS, present in Art. 15, Art. 65, Art. 69, Art. 91, and Art. 96.

Source: The authors, adapted based on Arts. 15, 20, 21, 91 and 98, as Annex 1.

Box 6 - Composition of portfolios more widespread in the studies carried out

Four articles refer to group elaborations (Art. 20, Art. 21, Art. 91, and Art. 68), being three in experiences with interprofessional groups (Art. 21, Art. 91, and Art. 96). In this way, teaching, learning and evaluating are mixed in this process, an action materialized by the portfolio. We identified that there is a search for truly holistic paradigms, in which multi-professional teams study together and work in teams, overcoming the unilateral and fragmented views of the phenomenon under study and of the conception of professional practice and, therefore, of the curriculum.

Although the Arts. 65 and 77 also consider the portfolio as a teaching, learning, and assessment method, they present open models for composition. Art. 65 refers to the pedagogical training of professors in the health area and considers all the activities carried out in the ten training meetings for the composition of the portfolio. Art. 77, when approaching the internship for the Dentistry course, does not make clear the movement of the portfolio during the process as a method of teaching and learning, and evaluation.

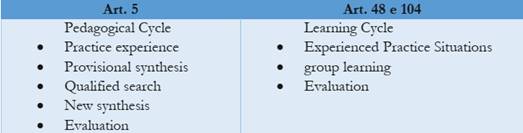

Portfolios as learning and assessment strategies

Although other models of structured portfolios also indicate learning cycles (Art. 5, Art. 104, and Art. 48), they do not conceptualize them as a method. They mention them as strategies that favor the learning and evaluation process. However, when analyzing the composition of the portfolios, Art. 5 shows that it is considered close to the methodology of problematization for historical-critical pedagogy (GASPARIM, 2002), a trend that is also progressive. The Arts. 48 and 104 approach the problem as they define the problems, raise hypotheses, learn from the group and make decisions. In all cases analyzed, the problems are those experienced and brought from the practice that students experience in the Health Units.

Source: The authors, adapted based on Arts. 5, 48, and 104, as Annex 1.

Box 7 - Portfolio composition according to problematization and PBL

In these cases, the portfolio could also be conceptualized as a teaching, learning, and assessment method because its composition reflects the movement adopted in the subject, which takes place in cycles, with different practical situations, in which teaching, learning, and assessment take place simultaneously.

Although the other articles that name the portfolio as a learning + evaluation strategy (Art. 66, Art. 47, Art. 61, and Art. 34) advocate the composition of the portfolio in an open way, highlighting some composition criteria, they value the production individually, during the process as a continuous act of delivering activities and reflections that support the collective discussions of the subject. These findings indicate coherence with the concept adopted: learning strategy + assessment, using other active methodologies simultaneously. There is a clear separation between what is a methodology and what is understood as learning and evaluating. The fact that they unify learning with evaluation means an advance in the concept of evaluation, in addition to being summative. The case of basic education (Art. 89) also followed this line, although with a structured model of portfolio composition.

Portfolios as a learning strategy

The articles (Art. 98, Art. 87, Art. 67, and Art. 55) that conceptualize portfolio only as a learning strategy do so using it simultaneously with some specific methodology, but all related to problematizations. The composition of the portfolio is always open, in the sense of highlighting what has been learned (synthesis of knowledge in theoretical or training subjects, case reports, and/or experiences in practical and internship situations), and, mainly, to reflect on them. Portfolios are designed individually, but delivery varies depending on the application context. These articles did not mention or reflect on the evaluative aspect of using the portfolio.

Portfolios as an evaluative resource

The articles that showed the portfolio only through the prism of evaluation (Art. 81, Art. 62, Art. 71, Art. 68, and Art. 78), as they are conventionally used in the literature, did not present a pattern to be considered. Three presented open models, and two others, structured models, although all are individual records. A clear definition of the delivery of productions was not identified, occurring in two cases at each meeting, as well as at the end of the semester. In the structured models, a crossing between still traditional models can be identified (Art. 62), in which the composition of the portfolio is fragmented into different activities, each with its value, as well as more innovative models, which integrate all elements of the learning process, as Art. 69, in a more unison way.

Source: The authors, adapted on Arts. 62 and 69, as in Annex 1.

Box 8 - Composition of portfolios evidencing different conceptions of learning

There are two similar ways of conceiving the portfolio as an evaluation procedure but with different learning concepts.

It is important to mention that the use of portfolios, to their composition, in the articles in which this identification was possible, in the field of health education, refers to internship and residency practices. In these practices, students can reflect on the actions taken, the problems faced, the decisions they made, the reflections, the learnings, and the reconstructions carried out with tutors, teachers, and colleagues, relating theory and practice and developing criticality, autonomy, and responsibility in the professional qualification. Teaching, learning, and assessment take place in real contexts, with authentic problems experienced. On the other hand, the other uses, more frequently, refer to the discipline of Health Policies, which, although it takes place within academic walls, proves to be critical and requires new visions and ideas, and new practices in the face of SUS.

Therefore, there are two fronts for using portfolios that refer to problem-solving. One of them is a teaching, learning, and assessment method, in which the portfolio is the methodology, or a learning and assessment strategy, where the portfolio is combined with other active methodologies. These findings go beyond the classic view of the portfolio as an evaluation procedure.

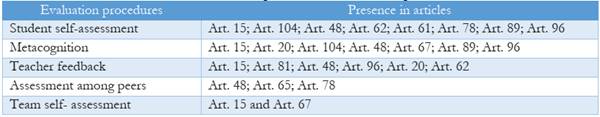

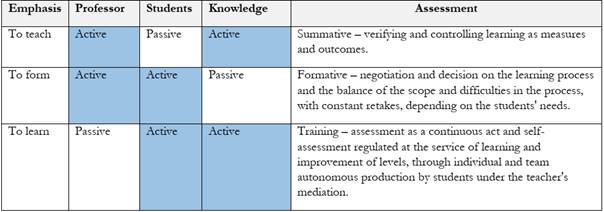

Pedagogical relations - portfolios and evaluative concepts

Deepening the analysis regarding assessment as a guiding element for the use of portfolios, concepts were identified such as formative assessment (also related to mediating assessment); formative + summative assessment (there are cases in which they are used together); assessment by competences; comprehensive assessment (in addition to cognitive skills); and diagnostic evaluation. Formative assessment, combined with competency and summative assessments, was the most used in the productions studied.

Box 9helps to understand that, according to the emphasis placed on the relationship between teacher, students, and knowledge, the practice of assessment may change. Thus, we can say that innovative paradigms tend to practice a formative and training assessment, as the concern with student learning is evident as a continuous act and resulting from its autonomous production in the process.

Source: The authors, based on Pinto (2016, p. 25-34).

Box 9 - Concepts of evaluation and emphasis on the triad of the pedagogical relationship

Formative assessment, present in Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 34, Art. 62, Art. 65, Art. 68, and Art. 71, is understood beyond the concept adopted in the reference above, that is, although the term formative is used, assessment is applied as a formative and coherent way from a theoretical-practical point of view. Therefore, the term “training evaluation”, according to Pinto (2006, 2016), is not commonly used in Brazil, in this study context.

Although not explicitly using the term formative assessment, Art. 5, Art. 61, Art. 87, Art. 91, Art. 96, and Art. 98, in the highlighted quotes, reveal this concept. Formative assessment in the productions, in addition to encompassing monitoring during the process, sharing what was built, teacher feedback, with indications for continuity and improvements in the process until the final delivery, involves self-assessment by students, as well as the metacognition, peer assessment, and teacher assessment.

When questioning the self-assessment purposes, Scallon (2015), for example, refers to the current use of forms with predefined assessment criteria about the task, so that the student self-assesses his production. For him, this is about self-correction, which can also be done in pairs or even in teams. In addition to self-correction, the student can perform self-regulation, which, according to Scallon (2015), consists of reflecting and recording or communicating the procedures followed to perform a task, a set of tasks, or the demonstration of the development of competence. In this report, the student indicates the paths followed, the facilities, the difficulties, and the strategies adopted to overcome them, in which he demonstrates thinking and reflecting on his learning process. These processes refer to metacognition as the possibility for the learner to demonstrate the awareness he has of himself in his learning process, to recognize his strengths and difficulties, and make decisions to improve what is necessary. Therefore, metacognition is related to self-regulation and self-assessment (BEBER; SILVA; BONFIGLIO, 2014; SCALLON, 2015).

The formative assessment associated with the summation was highlighted in Art. 104, Art. 48, Art. 66, Art. 67, and in Art. 89, which mentioned the possibility that, in the formative process, records are generated that can eventually be transformed into grades, meeting the institution's assessment system, to overcome the traditional models of only summative assessments.

The concept of assessment by competences is highlighted as necessary and important to meet the expected training profile. The following articles - Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 62, Art. 66, Art. 69, Art. 78, and Art. 98 - mentioned this possibility, since evaluation forms accompanied the portfolios to identify the competencies to be presented, such as critical analysis, the proposal of solutions, leadership, teamwork, among others. Art. 15, presents an assessment and self-assessment instrument by competences. Thus, they develop the self-correction and self-regulation advocated by Scalon (2015).

Together with the assessment by competence, Art. 69 used the summative assessment with relevant discussion on this issue. Art. 78 uses the term integral assessment, alongside assessment by competences, to indicate that, in addition to the cognitive domain, the psychomotor and socio-affective domains are also assessed. Finally, the diagnostic evaluation was mentioned by the experience of the portfolio in mathematics in basic education (Art. 89), combined with the concepts of formative and summative evaluation, and, in Art. 15, with competence-based and formative assessment.

Pedagogical relations - portfolios and evaluation procedures

Box 10shows that the evaluation process, although with different concepts, involves other procedures along with the use of the portfolio.

By adopting these assessment procedures, the portfolio goes beyond the students' productions, demonstrating the self-assessment process. For Butler (2006), this highlights the fact that the portfolio contains “evidence” of learning as well as “reflections” on this process. Thus, theoretical-methodological coherence is demonstrated, applying the concept of formative and training as indicated by Pinto (2006, 2016), which guarantees to care with learning, its progression, and reflection on this process.

Regarding the “reflections” that must be present in the constitution of portfolios, seven productions (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 81, Art. 48, Art. 65, Art. 91, and Art. 98) used the term “reflective portfolio”. However, mentions of thought and reflective processes were also prominent in the various productions. Two main meanings were identified for the term reflective: as a reflection on the learning process and as a reflection on the context in which the professional practice is being built.

Reflection on learning, as already mentioned, is about documenting, with records, the progress, advances, and potentialities, as well as the weaknesses and difficulties in the learning process, when constructive changes must point out transformations that have occurred. This was demonstrated in 20 of the 25 articles, that is, 80% of the productions (Art. 15, Art. 20, Art. 21, Art. 5, Art. 81, Art. 104, Art. 48, Art. 55, Art. 61, Art. 62, Art. 65, Art. 67, Art. 69, Art. 71, Art. 77, Art. 87, Art. 89, Art. 91, Art. 96 and Art. 98). The Art. 78 goes beyond the reflection on the student's learning process, highlighting the student's elaboration of a plan that helps him to deal with his difficulties, in search of personal, social and professional growth.

Reflection on the context of professional practice is another important aspect, especially in internship and residency practices (Art. 21, Art. 81, Art. 48, Art. 61, Art. 62, Art. 67, Art. 69, Art. 71, Art. 77, Art. 87, Art. 91, Art. 96 and Art. 98). Reflection constitutes a relevant critical process of lived experiences, in its multiple dimensions. It proposes to think about reality critically and look at it with clarity, scope, and depth, identifying problems and making decisions on ways to solve them to seek articulation and integration between theory and practice. It is also a time to review concepts, reaffirm ideas and attitudes, re-signify learning, establish relationships, and seek new knowledge, among other needs felt in the constitution of their professional identity.

Still using the “reflection” attribute, Art. 34, 65, and 66 mention it in the sense of “reflection of teaching practice”, in which the teacher, when narrating his professional experiences, transforms the representations of himself and his pedagogical practice. Thus, it is involved in the construction, reconstruction, and sharing of concepts, reflections, proposals, and actions, giving meaning to reports, studies, and theories, as well as feelings and values.

These attributes are in line with international trends, as Butler (2006) emphasizes that the use of the portfolio provides and encourages discussion with teachers and tutors and encourages reflection. In this sense, the term “reflective portfolio” is used indicating that, “while in teacher education, reflection is on the individual identities and beliefs of teachers”, in Medicine the focus is on the action, as well as on “teaching students to learn continuously” so that they can follow the changes and advances in medicine” (BUTLER, 2006, p. 6), which can be understood as important, for any area, beyond Medicine.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Through an integrative systematic review, we sought to answer the question: what is the relationship established between active methodologies and the use of portfolios as an evaluation procedure? In addition to tracing an overview of scientific production on the topic, we sought to reflect on the relationship between theory and practice from the perspective of complexity in education by approaching the themes in an interdependent way. Of the 115 articles collected on the Capes, Scielo, and Redalyc platforms, 25 articles remained selected through inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The systematic review revealed that most of the scientific production on the topic (92%) develops from a qualitative perspective. The analysis of practices in the use of active methodologies with evaluative portfolios occurs mostly (72%) in health education, in undergraduate courses. Another 20% refer to postgraduate courses and permanent education, also for health professionals in teacher training. Only two cases referred to other contexts: one for the Pedagogy course and another for basic education in Mathematics. Most of the productions took place from 2019 onwards, therefore, problems of study and current practices.

Three relationships can be identified that are established between the use of active methodologies and evaluative portfolios: legal relationships, educational relationships, and pedagogical relationships.

The legal and educational relationships point to the legal and educational frameworks that guide the practice and support the training processes, considering the training profiles and the contours of the desired professional training, especially for the field of health education. However, these relationships can inspire other areas and training fields as well. The study revealed that the choice of active methodologies and assessment portfolios is consistent with an integrated and interdisciplinary curriculum model, as well as studies and work in multidisciplinary or interprofessional teams. It was clear in the analyzes carried out that the practices are based on a holistic view of education, based on the paradigm of complexity, as well as on a critical formation, based on progressive trends in education, especially transformative education. It is possible to visualize the necessary rupture with the classic and conventional models of conceiving curricula and training practices. The considerable advance identified in terms of critical, creative, reflective, and active training profile, proposed in the DCN for health training and reflected in the analyzed practices, is also applicable to other professional training and educational levels, especially higher education.

Also, the analyzes show that comprehensive training is proposed and considers the student beyond the cognitive aspects, also covering the affective, socio-emotional, and psychomotor aspects, interdependently considering the human, professional and social dimensions. Training by competences, another strong indication of the use of active methodologies and reflective portfolios, is explicit in the concept of comprehensive training adopted in the analyzed studies. These practices can inspire other courses in which interprofessional teams can work together to solve practical problems, whether in undergraduate courses or engineering and related courses, for example.

In pedagogical relationships, an innovative trend discovered in this study is to consider the portfolio as an active methodology. The expression teaching, learning, and evaluation method are used to demonstrate that the practice of the portfolio, its composition, form of elaboration, frequency of meetings, and application context reveal the intertwining of teaching, learning, and evaluating, in continuous movement in the development of the discipline curriculum. In addition to assessment, the portfolio is also conceived as a learning and assessment strategy, being used simultaneously with other active methodologies, especially those involving problematization of the reality of professional practice. These findings go beyond the classic view of the portfolio as an evaluation procedure. There are two fronts for using the portfolios that refer to problem-solving. One of them is a teaching, learning, and assessment method, in which the portfolio is the methodology; or a learning and assessment strategy, where the portfolio is combined with other active methodologies.

In this sense, the study boosted the development of two concepts to understand the composition of portfolios: structured and open. The structured ones were conceived as those that follow a list of items, stages, or phases, to compose the portfolio, in a sequence to be followed with circularity in the process, and are particularly those that use the portfolio as a method of teaching, learning, and evaluation. The open ones are those that only indicate that the portfolio must contain reports, pointing out some elements to consider in the writing, usually narrative, about the activities, carried out in the classroom with peers or cases faced in the professional experience, individually or in groups. Although with variance in models and uses, open composition portfolios present a priori evaluation criteria, which is important to the evaluation process.

As expected, the study revealed that assessment practices with portfolios are based on the conceptions of formative and training assessments, but advance in the exemplification of assessment by competences, necessary for the development of the desired professional profile. Concerning the summative assessment, they problematize its practice, indicating possible paths for its accomplishment, considering the learning beyond the grades or mentions. They intertwine these trends in a clear and inspiring way for those who still encounter theoretical-practical difficulties.

In more specific relationships, the portfolio carries and reveals in this study an attribute as reflective. Reflective in the sense of providing opportunities for development and requiring reflection on the student's learning process and himself in the trajectory, as well as reflection on the context of future professional performance. In the case of teacher training, also in health, the reflection revolves around professional narratives, intending to be recognized as a professional, and the constructions and reconstructions made in this process, whether theoretical-practical, as well as feelings and values. This indicative demonstrates the application of self-evaluative and self-regulating processes, therefore, metacognitive in the formation of professional identity, future or in practice, practices recommended in educational innovations.

The scientific production found on basic education reveals the same aspects considered here in terms of educational and pedagogical relationships. It differs only in the legal relationships, which were restricted to indicating the evaluation process recommended by the LDB.

By a conclusive synthesis, this research confirms the international trend, which demonstrates greater use of portfolios in the area of health education, specifically in undergraduate courses in Medicine and Nursing, as well as in postgraduate teaching training or continuing education. In this way, it can be said that there is a gap in scientific productions, peer-reviewed, in which active methodologies and evaluative portfolios are used together as innovative pedagogical practices, whether in higher education, in addition to health education, or basic and professional education.

Acknowledgments:

CIDES PUCPR - Research Group on Teaching Creativity and Innovation in Higher Education, for the education and training in the use of the Atlas.ti Software.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Leonir P. Portfólios como instrumentos de avaliação dos processos de ensinagem. In: 26.ª REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ANPED, 5 a 8 de outubro de 2003, Poços de Caldas. p. 1-14. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.anped.org.br/sites/default/files/8_portfolios_como_instrumentos_de_avaliacao_dos_processos_de_ensinagem.pdf . Acesso em: 12 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

AUSUBEL, David P.; NOVAK, Joseph D.; HANESIAN, Helen. Psicologia educacional. Tradução de Eva Nick. Rio de Janeiro: Interamericana, 1980. [ Links ]

BEBER, Bernadétte; SILVA, Eduardo da; BONFIGLIO, Simoni U. Metacognição como processo da aprendizagem. Revista da Associação Brasileira de Psicopedagogia, ano 2014, v. 31. ed. 95. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.revistapsicopedagogia.com.br/detalhes/74/metacognicao-como-processo-da-aprendizagem . Acesso em:13 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BEHRENS, Marilda Aparecida. O paradigma emergente e a prática pedagógica. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2005. [ Links ]

BEHRENS, Marilda Aparecida. O portfólio como procedimento avaliativo. In: BEHRENS, Marilda Aparecida. Paradigma da c-omplexidade. Metodologia de projetos, contratos didáticos e portfólios. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes , 2008. p. 75-103. [ Links ]

BLANCO, Ascensión. (Coord.); HERRERAS, Bausela. Desarrollo y evaluación de competencias en Educación Superior. Madrid, Narcea. Bordón, Revista de Pedagogía, v. 61, n. 4, p. 155-156, 2009. 192 p. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/BORDON/article/view/28821 . Acesso em: 23 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

BODGAN, Roberto C.; BIKLEN, Sari K. Investigação qualitativa em educação: uma introdução à teoria e aos métodos. Editora: Porto Editora, 1994. [Coleção Ciências da Educação]. [ Links ]

BOTELHO, Louise L. R.; CUNHA, Cristiano C. de A.; MACEDO, Marcelo. O método da revisão integrativa nos estudos organizacionais. Gestão e Sociedade, Belo Horizonte, v. 5. n. 11, p. 121-136, maio/ago. 2011. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.21171/ges.v5i11.1220. Acesso em:5 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Philippa. A Review of the Literature on Portfolios and Electronic Portfolios. eCDF ePortfolio Project Massey University College of Education Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2006. Disponível em: (PDF) A Review of the Literature on Portfolios and Electronic Portfolios (researchgate.net). Acesso em: 10 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

COLL, Cesar. Significado e sentido na aprendizagem escolar: reflexão em torno do conceito de aprendizagem significativa. 2005. Disponível em: Disponível em: http:// www.php.gov.br/ensino/smed/cape/artigos/textos/césar.htpp . Acesso em: 11 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

DELORS, Jacques. Educação: um tesouro a descobrir. In: RELATÓRIO PARA A UNESCO DA COMISSÃO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE EDUCAÇÃO PARA O SÉCULO XXI.ED.96/WS/9, 2010. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109590_por . Acesso em:2 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

FERRARINI, Rosilei; SAHEB, Daniele; TORRES, Patricia L. Metodologias ativas e tecnologias digitais: aproximações e distinções. Revista Educação em Questão, Natal, v. 57, n. 52, p. 1-30, e- 15762, abr./jun. 2019. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2019v57n52ID15762. Acesso em:12 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Marcelo José M. et al. Novas Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para os cursos de Medicina: oportunidades para ressignificar a formação. Interface, Botucatu, v. 23, supl. 1, 2019. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/interface.170920. Acesso em: 2 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

FREIRE Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

FREIRE. Paulo. Pedagogia da esperança: um reencontro com a pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1992. [ Links ]

GASPARIM. João Luiz. Uma didática para a pedagogia histórico-crítica. 3. ed.Campinas: Autores Associados, 2002. [ Links ]

HADJI, Charles. A avaliação - regras do jogo: das intenções aos instrumentos. Portugal: Porto Editora, 1994. [ Links ]

HADJI, Charles. Avaliação desmistificada. Porto Alegre: Artmed Editora, 2001. [ Links ]

HOFFMANN, Jussara Maria L. Avaliação mediadora: uma prática em construção da pré-escola à universidade. Porto Alegre: Educação & Realidade, 1993. [ Links ]

HOFFMANN, Jussara Maria L. Pontos e contrapontos: do pensar ao agir em avaliação. 2. ed.Porto Alegre: Mediação, 1998. [ Links ]

LIMA, Valéria V. Competência: distintas abordagens e implicações na formação de profissionais de saúde. Interface, Botucatu, v. 9, n. 17, p. 369-78, 2005. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832005000200012. Acesso em: 23 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

LIMA, Valéria V. Espiral construtivista: uma metodologia ativa de ensino-aprendizagem. Interface, Botucatu, v. 21, n. 61, p. 421-34, 2017. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622016.0316. Acesso em: 23 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

LIMA, Valéria V. et al. Processo de construção de perfil de competência de profissionais. São Paulo: Hospital Sírio-Libanês, 2014. (Série Nota Técnica n.º 1). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://iep.hospitalsiriolibanes.org.br/Documents/LatoSensu/nota-tecnica-competencia-profissionais.pdf . Acesso em: 23 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

LUCKESI, Cipriano C. Avaliação da aprendizagem escolar. 8. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1998. [ Links ]

MIRANDA, Fernanda Maria; ZEN-MASCARENHAS, Silvia Helena. Caracterização de portfólios digitais: revisão integrativa da literatura. J. Health Inform, v. 10, n. 3, p. 88-94, jul./set. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.jhi-sbis.saude.ws/ojs-jhi/index.php/jhi-sbis/article/view/547/338 . Acesso em:25 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

MIRANDA, Joseval dos R. O webfólio como procedimento avaliativo no processo de aprendizagens: sentidos, significados e desafios. Revista Informática na Educação: teoria & prática, Porto Alegre, v. 20, n. 2, maio/ago. 2017. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-1654.63731. Acesso em: 11 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

MORAN, José. Metodologias ativas para uma aprendizagem mais profunda. In: MORAN, José; BACICH, Lilian(Orgs.). Metodologias ativas para uma educação inovadora: uma abordagem teórico-prática. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2018. p. 1-23. [ Links ]

MORIN, Edgar. A cabeça bem-feita: repensar a reforma, reformar o pensamento. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2000. [ Links ]

MORIN, Edgar. Introdução ao pensamento complexo. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2007. [ Links ]

MORIN, Edgar. Os sete saberes necessários à educação do futuro. 2. ed. Tradução de Catarina Eleonora F. da Silva e Jeanne Sawaya. São Paulo/Brasília-DF: Cortez/Unesco, 2001. [ Links ]

PERRENOUD, Philippe. Avaliação da excelência: a regulação das aprendizagens entre duas lógicas. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1999a. [ Links ]

PERRENOUD, Philippe. Construir as competências desde a escola. Porto Alegre: Artmed Editora, 1999b. [ Links ]

PINTO, Jorge. A avaliação em educação: da linearidade dos usos à complexidade das práticas. In: AMANTE, Lúcia; OLIVEIRA, Isolina. Avaliação das aprendizagens: perspectivas, contextos e práticas. Laboratório de Educação a Distância e eLearning (LE@D). Portugal: Universidade Aberta-LE@D, 2016. p. 03-40. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://repositorioaberto.uab.pt/bitstream/10400.2/6114/1/ebookLEaD_3%20%282%29.pdf . Acesso em: 6 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

PINTO, Jorge. Evolução das concepções teóricas da avaliação. In: PINTO, Jorge; SANTOS, Leonor. Modelos de avaliação das aprendizagens. Lisboa: Universidade Aberta, 2006. p. 1 - 47. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.aprofs.net/aldora/Modelos%20de%20avalia%E7%E3o%20das%20aprendizagens%20(e-book).pdf . Acesso em: 6 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

SALDAÑA, Johnny. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Second Edition. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2013. [ Links ]

SCALLON, Gérard. Portfólio: uma ferramenta para estimular a autoavaliação. In: SCALLON, Gérard. Avaliação da aprendizagem numa abordagem por competências. Curitiba: PUCPRess, 2015. p. 357-382. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, Celso dos S. Avaliação: concepção dialética-libertadora do processo de avaliação escolar. 14. ed. São Paulo: Libertad, 2000. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, Celso dos S. Avaliação da aprendizagem - práticas de mudança: por uma práxis transformadora. São Paulo: Libertad , 2003. [ Links ]

VASCONCELLOS, Celso dos S. Superação da lógica classificatória e excludente da avaliação. São Paulo: Libertad , 1998. [ Links ]

VILLAS BOAS, Benigna Maria F. O portfólio no curso de pedagogia: ampliando o diálogo entre professor e aluno. Revista Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 26, n. 90, p. 291-306, jan./abr. 2005. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302005000100013. Acesso em:12 jan. 2021. [ Links ]

VILLAS BOAS, Benigna Maria F. Portfólio, avaliação e trabalho pedagógico. 1. ed. São Paulo: Papirus Editora, 2013. [ Links ]

8The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG - through the program of supporting the publication of institutional scientific journals.

Received: May 26, 2021; Accepted: March 21, 2022

texto en

texto en