Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 15-Nov-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469836572

Article

CURRICULUM POLICIES AND THEIR ARTICULATIONS ON THE PERSPECTIVE OF A MORE DEMOCRATIC EDUCATION 1

2Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos (UNISINOS). São Leopoldo, RS, Brasil.

3 Universidade do Porto. Porto, Portugal.

4 Universidade do Estado da Bahia (UNEB). Santo Antônio de Jesus, BA, Brasil.

By focusing on curricular policies for basic education, this article aimed at bringing to the academic debate sphere questions related to the Brazilian National Core Curriculum (BNCC) and the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul (RCG) and, subsequently, its influences on the Curricular Guiding Document of a City Territory (DOCT-SL/RS). Based on a qualitative approach that uses document analysis associated with the Social Media Analysis method, this study revealed that the participation of civil society and school communities in the curricula policies production is limited to some representations and public consultations. Results also indicate that the BNCC as a macro strategy constitutes a document that has an excessively prescribing and operational nature and, thus, is limited for its explicitness and restricted as to the outlining of guidelines for its unfolding at state and city levels. From an attentive reading of the RCG, it was possible to infer that it is a pedagogical proposal centered around developing competencies with more conceptual expression in the BNCC than in the city document itself. The results of this study also identified the existence of aspects that do not comply with the collaboration regimen to elaborate and produce texts of the mentioned documents revealing the lack of articulation between state and city processes, highlighting the lack of participation, throughout the writing of these texts, of both federative entities and other representative actors of civil society and school communities.

Keywords: Curriculum; Curricular Policies; Brazilian National Core Curriculum; Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul; Curricular Guiding Document of a City Territory

O presente artigo, ao focar as políticas curriculares para a educação básica, teve como objetivo trazer ao debate acadêmico questões relacionadas com a Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC) e o Referencial Curricular Gaúcho (RCG) e suas influências no Documento Orientador Curricular de um Território Municipal (DOCT-SL/RS). Apoiado em uma abordagem qualitativa, que utiliza o recurso metodológico da análise documental associado à Análise de Redes Sociais, o estudo aqui apresentado mostrou que a participação da sociedade civil e das comunidades escolares na produção das políticas curriculares restringe-se, em geral, a algumas representações e consultas públicas. Os resultados indicaram, também, que a BNCC como estratégia macro traduz-se em um documento excessivamente prescritivo e operacional e, assim, limitado quanto à explicitação e ao delineamento de diretrizes e orientações para seus desdobramentos nas esferas estadual e municipal. A partir da leitura cuidadosa do RCG, foi possível inferir que ele é uma proposta pedagógica centrada no desenvolvimento de competências, que tem mais expressão conceitual na BNCC do que no documento municipal. Os resultados da pesquisa identificaram, ainda, a existência de aspectos que não comungam com o regime de colaboração, pois a elaboração e a produção dos textos dos referidos documentos evidenciam desarticulações entre os processos estadual e municipal, com destaque para a ausência de participação, na escrita desses textos, de ambos os entes federativos e de outros atores representativos da sociedade civil e das comunidades escolares.

Palavras-chave: Currículo; Políticas Curriculares; Base Nacional Comum Curricular; Referencial Curricular Gaúcho; Documento Orientador Curricular de um Território Municipal

El presente artículo, al centrarse en las políticas curriculares para la educación básica, busca reflexionar sobre la Base Nacional Común Curricular (BNCC) y el Referencial Curricular Gaúcho (RCG) y sus influencias sobre el Documento Orientador Curricular de un Territorio Municipal (DOCT-SL/RS). Apoyado por una investigación de abordaje cualitativo que emplea el recurso metodológico del análisis documental combinado con el Análisis de Redes Sociales, el estudio presentado aquí mostró que la participación de la sociedad civil y de las comunidades escolares en la producción de políticas curriculares, por lo general, se restringe a algunas representaciones y consultas públicas. Los resultados también indicaron que la BNCC como estrategia macro se traduce en un documento excesivamente prescriptivo y operacional y, así, limitado cuanto a la explicitación y delineamiento de directrices y orientaciones para sus desdoblamientos a niveles estatal y municipal. De la lectura cuidadosa del RCG, fue posible inferir que se trata de una propuesta pedagógica centrada en el desarrollo de competencias, tiene mayor adherencia conceptual que el documento municipal a la BNCC. También se identificaron aspectos que no coinciden con el régimen de colaboración, pues la elaboración y la producción de los textos revelan desarticulaciones entre el proceso estatal y municipal, especialmente cuanto a la ausencia de participación de ambas entidades federativas y de otros actores representativos de la sociedad civil y de las comunidades escolares.

Palabras clave: Currículo; Políticas Corriculares; Base Nacional Común Curricular; Referencial Curricular Gaúcho; Documento Orientador Curricular de un Territorio Municipal

INTRODUCTION

Having as a theme the Brazilian curricular policies in the perspective of more democratic education, this article is based, at its core, on the Curricular Guiding Document of the São Leopoldo/RS Territory (DOCT-SL/RS), located at the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul State (RS), and its articulations with the Brazilian National Core Curriculum (BNCC) and the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul (RCG). This set of district schools, our investigation locus, is located, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2010), in a city with approximately 215 thousand habitants, and, according to the Anísio Teixeira National Institute for Educational Research and Studies (INEP, 2019), it counts with 1,267 educators and 23,603 students distributed throughout 49 schools. Only one of these is located in a rural setting and has 123 students.

By mapping the literature on curricular policies in Brazil, we evoke the state art developed by Rosa and Ponce (2016), published in the e-Curriculum journal, on curricular policies for basic-level education regarding the period from 2010 to 2015. In this sense, the authors concluded that we currently live in an educational context whose worry related to markedly cognitive and productivist conceptions in the role of education and school in Brazilian curricular policies and other countries, especially on educators’ formation and work, have become increasingly urgent. Based on this conclusion, this article’s study aimed to promote a conceptual discussion by analyzing the previously mentioned documents. Regarding this theme, other studies related to High School and Vocational Training also deserve to be highlighted (BRANCO et al., 2019; COSTA; LOPES, 2018; FERRETI; SILVA, 2017; HERNANDES, 2020; MENDONÇA; FIALHO, 2020; SILVA, M. R., 2018; SILVA, R. R. D., 2018, 2020).

Regarding curricular reform, worries regarding the non-confrontation of Brazilian educational inequalities are relevant (KOEPSEL; GARCIA; CZERNISZ, 2020) for they do not problem-pose the material conditions of public schools and the exercise of teaching (GIROTTO, 2019), which, in practical terms, makes educators responsible for the results in educative processes (FREITAS; SILVA; LEITE, 2018) For Macedo (2015, p. 94), there is, “in curriculum, as well as in every signifying practice, a wish for control, a reduction of several senses to the ones made possible through power dynamics while social justice cannot do without singular subjects in its concreteness.”

In compliance with these studies, we consider important the critical analysis of relations set between city curricular policies - Curricular Guiding Document of the São Leopoldo/RS Territory (DOCT-SL/RS) - and policies concerning the state - Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul - and the country - Brazilian National Core Curriculum (BRASIL, 2017) - in the scenario of BNCC implementation. We clarify that the school curriculum cannot be seen exclusively as an official document, nor as a text that is prescribed and/or a list of objectives, methodologies, and assessments for a certain education level (FERNANDES, 2012; FERRAÇO; CARVALHO, 2012; LEITE, 2002a, 2002b). It is necessary to take it, also, in its practical dimension, that is, as a praxis that is capable of assuring a permanent (re)construction, since praxis is linked to a practical and theoretical context that is dialectal, and, therefore, dynamic, enabling the generation of new forms for experiencing education. It means that we can understand the curriculum as praxis precisely in school contexts, everyday school routines, and in curricular practices of educators (FREIRE, 1981, 1996, 2001, 2002, 2005), in which recontextualizing and re-defining happens (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016).

When one talks about curricular policies, one is prone to think about implementation and, consequently, the important role that both school communities and educators have when implementing these policies. One is inclined to assume that each school system and each school, with their school communities, make sense of the curricular policies, reiterating and refracting them (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016) as well as aligning them with democratic educational policies. In this light, the study presented in this article answers the following research question: what happens in processes of text production belonging to the field of curricular studies regarding city context policies (DOCT-SL/RS), in its relation with the national (BNCC) and state (RCG) contexts, considering the specificities and peculiarities of each reality and the articulations on the perspective of more democratic education?

In its structure, this article, in addition to the introduction, also counts with the following sections: “Theoretical Framework,” “Methodological Procedures,” “The Production of Curriculum Policies Texts in Focus,” “Visiting Key Concepts on the Field of Curriculum Policies,” and “Final Remarks.”

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

By focusing primarily on curricular studies, we present a dialog with authors of the educational field focused on democratic education as a contribution to social and curricular justice. As stated by Connell (1999), there are three reasons to justify the importance of the theme of social justice for educators, parents, students, managers, and administrators of federal bodies5. The first reason is related to the fact that the educational system is a public asset of great importance and is provided by an unequal distribution of resources in formal education and has unequal results in terms of social access. The second reason concerns that the educational system is not only a current public asset but will continue to be since organized knowledge is increasingly being converted into the most important component of the productive system. Additionally, the educational system not only distributes current social assets but also complies with the type of society. Thus, getting society to be fair depends partially on the usage we perform of the educational system, how it is organized, and its priorities.

The third reason that endorses the relevance of the social justice theme is linked to the question of what consists of the act of educating, given that teaching and learning, as social practices, always raise questions about action proposals and criteria, resources application, and responsibility, and consequences of educational and social actions. Under this perspective, the assumption indicates that a greater curricular (SANTOMÉ, 2013) and cognitive (CORTESÃO, 2011) justice leads to social justice (CONNELL, 1995, 1999, 2012). For it to occur, educational policies that follow this matrix need to recognize that the school and its agents have the power to decide on processes of elaborating a curriculum that solidifies social justice principles (LEITE, 2002a, 2002b, 2012; SAMPAIO; LEITE, 2017). This is the primary assumption in a school project from everyone and for everyone, that is, a school that seeks to comply with and construct the principle of opportunity equality for all social groups, for which education is destined.

A democratic education implies curricular policies sustained by principles and foundations of social and curricular justice. It is worth noting that the academic literature from a long time ago recognizes both the neutrality of curricula and knowledge on elaboration and construction of principles of democratic education (GIROUX, 1993; SILVA, 2004; LEITE, 2002b, 2012), as well as the importance of providing context to the prescribed curriculum, in a way that it contemplates local situations and specificities of distinct students (LEITE; FERNANDES; FIGUEIREDO, 2018, 2019). Recognizing that the school and curriculum are not neutral, as they transmit and privilege values that influence the social recognition of some knowledge. Cultural characteristics are essential for creating conditions that promote equality of opportunities and school success. Moreover, we know that the everyday routine is a privileged space to produce curricular practices since “curricula go beyond what one may understand through texts that define and explain school proposals” (REIS, 2016, p. 1334).

In this light, we understand the Brazilian national curriculum as a project that is constructed by action (LEITE, 2005; LEITE; FERNANDES; FIGUEIREDO, 2018, 2019), in which educators, as developers of the curriculum (LEITE; FERNANDES, 2010, 2011), make use of their autonomy on decision-making processes of in-context curricula. For the solidification of this action, one must take into consideration that “[...] valid knowledge for numerous children is the knowledge that is directly related to their social realities, a knowledge that allows them to be intertwined into activities that are valued by themselves” (SMITH, 2002, p. 7). Thus, an in-context curriculum based on social and cognitive justice that surpasses what is expected by curricular documents (REIS, 2016) must bring the school space to the everyday routine experiences of all students. In this sense, additionally, Connell (1999, p. 70) declared that “[...] the principles of curricular justice should help us cleaning, a little, the house of education, as well as identifying curricular aspects that are socially unequal.” For this, it is necessary to consider the following principles: the principle of interest of the less favored, which is denied by curricular practices that comply with this situation; the principle of participation, which is denied when practices that enable some groups to have more engagement than others on decision-making processes; and the principle of the historical production of equality, which is denied when there are obstacles to changes in this direction. Ponce and Neri (2015) also note that the search for curricular justice is necessary. The curricular practice is a key for this process in the three fundamental decisions of the curriculum: the one about the required knowledge for individuals contemplated by the curriculum to prepare themselves to understand the world, the one relating to the care with these individuals that are involved in the teaching process, in a way that grants everyone the proper conditions for development; and the one relating to the democratic, solidary coexistence that has to be promoted in school.

Efforts for an educational policy that complies with these conditions, therefore making it democratic, inclusive, and possible to enable quality learning, is related to the concept of a school with an intelligent curriculum (LEITE, 2003), that is, a school in which there are collective decision-making processes, a school that continually challenges itself for implementing internal and external dynamics that contribute for bettering the education quality of its students. In this light, one should also consider the importance that educators, managers, and other actors of the educational community development agency power that will grant them a more active role in decision-making processes and the construction of positive changes (PRIESTLEY; BIESTA; ROBINSON, 2013, 2015; SANTOS; LEITE, 2020).

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

From a methodological point of view, in this study, we followed a procedure of qualitative orientation, which appealed to documental analysis as prescribed by Cellard (2012) for investigating the following documents: Brazilian National Core Curriculum, in a national level, Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul, in a state level, and the Curricular Guiding Document from the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre, in a city level. In compliance with Cellard (2012, p. 295), we recognize that “the written document constitutes an extremely precious source for all researchers from the Social Sciences” and that the document analysis occurs in two steps: the preliminary analysis and the analysis itself. The preliminary analysis encompasses context, author authors, the authenticity and reliability of the text, the text’s nature, key concepts, and the internal logic of the text. According to the author, these dimensions allow the researcher to access the document and carry out a coherent interpretation, keeping in mind the theme or their initial questionings and if it is not comported in a rigid method but in interpretations that “are the result of the researcher’s choices regarding the problem and the theme of their investigation, as well as their theoretical preferences” (CELLAR, 2012, p. 314). Ergo, it is noteworthy to mention that the corpus of documents used in this research consists of official documents pertaining to curricular policies. These documents allow us access to rich data and are authentic and reliable sources, in compliance with what the author recommends for the preliminary analysis state. Thus, in this study, we explore the following elements: context, author(s), nature of the text, and key concepts.

The context is primordial for the development of the other stages, for it encompasses the social, cultural, economic, and political scenario in which a document is produced and allows the researcher, as stated by Cellard (2012, p. 299), “to learn conceptual schemes of its actor or actors, understanding their relation, identifying the people, social group, facts it references to, etc.” The author also adds that “one cannot even think about interpreting a text without having, priorly, a good idea on the person that expressed it, their interests, and motives that lead them to write the text” (CELLARD, 2012, p. 300). Thus, we were interested in registering the authors that produced the texts/documents and what they represented.

As for the nature of the texts, even though these are regulatory, official documents of curricular policies, we considered the structure and internal logic of each of them and the period in which they were published. Regarding key concepts, since they were analyzed with the intention of us comprehending the meaning of the terms employed by the author(s) of the text(s), they were discussed during the second stage of analysis. In turn, key concepts that were selected for the analysis are also in accordance with Fujita (2004, p. 258), who defined them as “a representation of the meaningful content of the text” and, as stated by Ludke and André (1986), they can also be called “categories of analysis.” As supported by the last two authors, it is crucial to consider that “there are no fixated norms nor standardized procedures for the creation of categories, although it is worth noting that there is a consistent theoretical framework that may help an initial, more safe and relevant selection.” In compliance with this idea, in this study, the key concepts chosen constitute categories of analysis for investigating the priorly mentioned documents (BNCC, RCG, and DOCT-SL/RS). This choice came from the theoretical-methodological referential that bases this study. For an in-depth understanding and analysis of the sense of curricular policies, the object of this research, we opted for the adoption of the following set of key concepts, which are intrinsically related to the curricular policy and studies from the field: education and school education; curriculum, teaching, and assessing; types of learning, essential learning, and competencies; and educator and student. At this moment, we revisit the ideas of Fernandes (2012), Ferraço and Carvalho (2012), and Leite (2002), who affirmed that the curriculum could not be conceived only as an official document since it needs to be understood, too, as a praxis, referring to a practical-theoretical context that is also dialectic, and, therefore, dynamic, generating new forms of experimenting education.

The second stage of this method, called “analysis” (CELLARD, 2012), proposes to produce or redo pieces of knowledge and create ways to understand phenomena, offering the researcher the tools to carry out a coherent interpretation of the object of study. Additionally, the “analysis” stage allows the researcher to interpret documents, summarize information, determine tendencies, and make inferences as far as possible. As stated by the author, “the possible combinations between the different elements contained in the sources establish themselves in regard to the context, the problem, or the theoretical chart, but, also, we should admit it in regard to the researcher’s personality and their theoretical or ideological position” (CELLARD, 2012, p. 304). In this study, the analysis stage itself it called “comparative analysis,” which, as indicated by the name, consists of carrying out a compared analysis between the documents researched and showing how key concepts appear in each one of them. We also highlight that the analysis of key concepts carried out both through the first stage of the document analysis method by Cellard (2012), called “preliminary analysis,” and through the second stage, called “analysis,” occurs in section “Visiting Key Concepts on the Field of Curriculum Policies.” The key concepts were extracted from the documents in compliance with the research proposals, respecting the stages of the adopted method. As a searching procedure in documents, we used the “find” tool (Ctrl/Command+F), using as descriptors the expressions and synonyms of analysis categories and registering their occurrence. Moreover, regarding content clarification, in this study, we opted for the excerpt of phrases, for isolated words could reduce or minimize the interpretation of meaning expressed in the text.

We also highlight that the arguments presented here are supported by the approach of the Social Media Analysis method (SMA), which, for Recuero (2017), is a study perspective of social groups that enables the systematic analysis from specific measures surrounding the structure of these groups. It is linked to an approach rooted in Sociometry and Graph Theory (RECUERO; BASTOS; ZAGO, 2015). Since it is not only a method but also an approach toward social groups, the option by the SMA assumes that the social group is a network that can be analyzed through some specific methodological premises. Referring to this method, Viseu and Carvalho (2020, p. 3) stated:

From 1960 onwards, in the United States and the United Kingdom, mainly, that emerged the first forays of studies on public policies regarding the fragmentation of processes and political decision-making, as well as the role played by several interested groups along with political-administrative elites (Thatcher, 2004). Heirs of these first investigations, the studies on public policies started referring to the network concept for the study of the relations between the State and certain collective actors (professional associations, companies, unions, etc.).

One can note, from the abovementioned excerpt, that there is a symbiotic relationship with a mutuality character due to the behavioral mode of the State of doing politics. When governance substitutes the Nation-State governments, network analyses grow. Corroborating this perspective, Avelar and Ball (2019, p. 65) affirmed that:

Changing relationships between the State and society is an international phenomenon, despite considerable variation. Generally speaking, states now increasingly share governing with other social actors (Bevir, 2011). Decision-making processes and implementation systems used to be mainly executed by the State are increasingly dispersed in complex networks of non-governmental institutions and agencies. While the boundaries between the State, economy, and civil society have always been thin and fuzzy, relations across those boundaries have assumed a new stridency and intensity in the past 30 years. (Our translation).

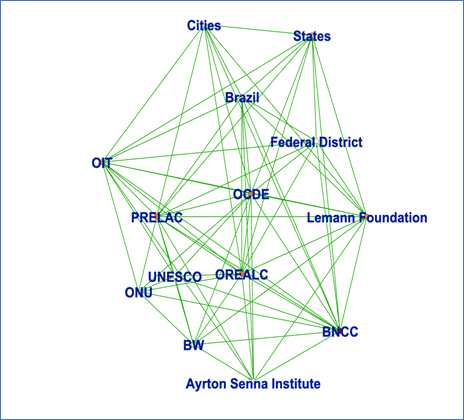

In Figure 1, we exemplify this relation, which is sometimes directed and sometimes not, constituting a mixed graph formed by international and national organisms, federative bodies (states, the Federal District, and cities), and private companies, which hierarchically6 act for the normalization, through education or competency, Brazilian basic education.

THE PRODUCTION OF CURRICULUM POLICIES TEXTS IN FOCUS

In this section, we explore elements related to the context, authors, and nature of the texts of the Brazilian National Core Curriculum, the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul State, and the Curricular Guiding Document from the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre

Context

The Brazilian National Core Curriculum is the educational policy belonging to the curriculum field, which guides curricula, teaching processes, learning, and assessment at a national level. The production of the focused city and state curricular policies takes place in the Brazilian educational scenario of the BNCC implementation (BRASIL, 2017), guided by the Support Program for BNCC Implementation (ProBNCC), instituted by Ordinance no. 331, dated April 5, 2018, from the Education Ministry (MEC) (BRASIL, 2018). The Art. 1 of this Ordinance institutes ProBNCC, aiming at guiding the Federal Unity (UF) through State Departments and Education Districts (SEDEs), as well as the City Departments of Education (SMEDs), in the process of reviewing or elaborating and implementing curricula aligned with the BNCC, in a collaboration regimen between states, the Federal District, and cities. This ordinance was changed by Ordinance no. 756, dated April 3, 2019, from MEC (BRASIL, 2019), which includes specific aspects of the BNCC implementation for High School.

BNCC is a document of national reference that guides the formulation of system curricula and education networks of the states, the Federal District, and cities, and, consequently, the politic-teaching projects of the country’s educational institutions. This document integrates the national policy of basic education, contributing to the alignment of other policies and actions at a federal, state, and city level referring to the formation of educators, assessments, the elaboration of educational content, and criteria for the offering of adequate infrastructure for the maximum development of instruction. BNCC proposes helping surpass the fragmentation of educational policies given that it encourages strengthening the collaboration regiment between the three government spheres (BRASIL, 2017).

At the same time, in the section that deals with the inter-federative pact and its implementations, this document highlights the autonomy of federal entities:

In Brazil, a country based on the autonomy of federated entities, accentuated cultural diversity. Deep social inequalities, the systems, and teaching networks should elaborate curricula. Schools need to elaborate teaching proposals that contemplate the students’ necessities, possibilities, interests, and linguistic, ethnic, and cultural identities. (BRASIL, 2017, p. 15).

In this regard, we highlight that the term “system” refers to the set of educational institutions of a specific state or city, and “network” refers to the set of educational institutions administratively subordinated to another.

In the 2019 Guiding Document of the Support Program for BNCC Implementation (ProBNCC), there are references and details concerning the following supports for curricula reviews:

. Financial support via Articulated Actions Plan - PAR to the Seduc, aiming at granting: (i) technical quality on the curricular document elaboration in a collaboration regimen set between states, the Federal District, and cities for all Basic Education, and (ii) the implementation of the curricula elaborated in compliance with BNCC;

. Formation, offered by MEC, to curricular teams and the management of the Program in the states; and

. Technical assistance that contemplates: (i) payment of educational grants for educators belonging to the ProBNCC team via FNDE (ii) hiring of management analysts, (iii) a specific MEC team for providing support on the national management of the The program, (iv) support material, and (v) a virtual platform for supporting and (re)elaborating the curriculum and public consultations. (BRASIL, 2019, p.4)

On the MEC website, there are available resources and a diverse set of supporting materials in the “Implementation” tab on the BNCC page (BRASIL, 2017). In the document titled Complementary material for the (re)elaboration of curricula, topic 1 presents elements for the basic structuring of curricular documents, as follows: introductory text (central elements); curricular history and description of the elaboration process of the document; legal milestones that support the curricular document; definition of the subjects that want to graduate; definition of teaching and learning principles and concepts; discussion on competencies and abilities; general guidelines concerning what the student should know, how to teach and/or assess; indication of cross-cutting and integrating themes related to the current themes required by law and specific rules; profile of subjects through the different stages and modes of basic education; consideration on curricular implementation; explanation on the codes used; curricular organizer (usually presented in the form of a chart); and modes of organization and grouping of abilities and/or knowledge objects (an aspect directly related to the learnings that should be granted to the students).

In this sense, RCG and DOCT-SL/RS are the results of the process of implementation prescribed by the ProBNCC Program for the (re)elaboration of state and city curricula. In the Rio Grande do Sul State, the unfolding of BNCC has led to the production of the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul, which guided, until August 2021, the implementation of the Childhood Education and the Elementary School - through this first moment, RCG did not include High School since its in the public consultancy phase and available at the Education Department of Rio Grande do Sul (SEDUC-RS) website. Rescission no. 345/2018, elaborated by the State Council of Education of Rio Grande do Sul (CEEd-RS), institutes and guides the RCG implementation, affirming that it should be respected, compulsorily, throughout the stages and modes of basic education (Elementary School and Childhood Education), and support school curricula of state, city, and private schools in the Rio Grande do Sul territory (CONSELHO ESTADUAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, 2018). Thus, this Rescission highlights an idea of the coverage of RCG in school networks of the Rio Grande do Sul State.

Encompassing this idea, Art. 3 of the abovementioned Rescission establishes the RCG as a compulsory reference for all educational establishments set through the state territory, broadening its coverage. In the same article, there is a recommendation for the adequacy, or elaboration, of the Political-Teaching Proposals (also known as Political-Teaching Projects) and school curricula. At the final and transitory dispositions of Art. 21, there is a deadline for this adequacy, or elaboration, under what the RCG proposes — the year of 2019, and for the implementation of this Referential — beginning of the school year of 2020, in compliance with the autonomy of the teaching systems and establishments. The schedule of the BNCC implementation anticipated that the process of curriculum (re)elaboration should occur during the year 2018 in a collaboration regimen. It is possible to note, however, that the schedule is late, given that High School, until this moment, has no guiding document of a maintaining institution; all that happened was the implantation of the New High School pilot in some selected schools.

In turn, the Curricular Guiding Document of the City Territory (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 10) “is a reference for the establishment of principles and conceptions and base/guide school curricula and related management productions, elaborated by teaching institutions of this territory [the Rio Grande do Sul State].” Produced between 2018 and 2020, the educational context surrounding the production of this document was marked by delays in the BNCC schedule implementation and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors

Three distinct versions of the BNCC were elaborated until its final formulation, which occurred in a stage of disputes between political actors from two federal governments: the one by Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), belonging to the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT), who claims to be left-wing and to have suffered a coup on 2016 (FREIXO; RODRIGUES, 2016), and another one by president Michel Temer (2016-2019), belonging to the Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (MDP), considered to be a center party that gathers diverse ideologies with a right-wing tendency. The BNCC implementation has been occurring through the government by Jair Bolsonaro (2019-), elected by the Partido Social Liberal (PSL), aligned to social-liberalism. Nonetheless, he is in the Partido Liberal (PL). In this sense, there is a strong influence and participation in the elaboration of the BNCC by different private actors that present themselves as affiliated with the main public agents — the Education Ministry, National Union of the City Education Leaders (UNDIME), National Council of Education Secretaries (CONSED), and the National Education Council (CNE) —, and which, according to Macedo (2014, p. 1540), constitute “philanthropic institutions, large financial corporations that shift taxes to their foundations, producers of educational materials linked or not to the large international corporations in the sector.” There are, presented below, examples of these private actors: Gerdau, Natura, Santander, Bradesco, Fundação Roberto Marinho and Fundação Lemann, whose discourses claim the defense of the importance of a national curriculum (MACEDO, 2014).

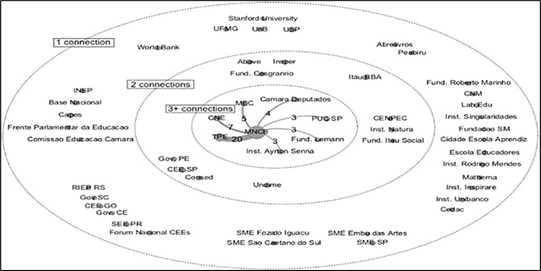

In Brazil, a country of dependent capitalism (FERNANDES, 1976), it is possible to note a dependence on the elaboration, production, and diffusion of knowledge that is aligned, usually, to the hegemonic thought of countries with a neoliberal ideology, reproduced by educational rules by federal entities. In compliance with this, in Figure 2, generated by the graph produced by the research by Avelar and Ball (2019), we can note the power dynamic of Brazil’s National Core Curriculum Movement (MNBC). MNBC may be considered a set of natural persons and legal entities that influence the management-oriented manner of minimal State and vocational competency education within the BNCC context.

Source: Avelar and Ball (2019, p. 69).

FIGURE 2 - Power dynamic of Brazil’s National Core Curriculum Movement

We can observe, in Figure 2, approximations in three spheres, until the arrival of the power core, at the center, which demonstrates where the MNBC participants are distributed, therefore influencing the elaboration of public policies, especially the BNCC, which, by rules, reflects at the RCG and DOCT-SL/RS. Figure 3, in turn, shows companies that support the MNBC, influencing and determining the ways that have formatted the norms of education by competence, which are grouped in the BNCC.

Source: Avelar and Ball (2019, p. 69).

FIGURE 3 - Companies that support Brazil’s National Core Curriculum Movement

The RCG, in turn, was produced during the government by José Ivo Sartori (2015-2019), belonging to the Movimento Democrático Brasileiro (MDB), and is being implemented during the term of Eduardo Leite (2019-2022) (Rio Grande do Sul State governor), belonging to the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (PSDB) aligned to the center-right wing that presents an action manner that is very similar to the ones by private actors during the RCG implementation process.

DOCT-SL/RS, which was produced and is being implemented by the government by Ary José Vanazzi (2017-) (PT), who was re-elected for another term as mayor in 2021, has a characteristic that distinguishes it from the other documents: in its elaboration process, there is no register of the participation of private actors, except for public and private school institutions. We highlight that the DOCT-SL/RS had, during its production, the prominence of the city education network in the executive coordination of the document, counting with actors from the office of the secretary of education, basic management directorate, the pedagogical advisory, and other technical advisory directorates. In addition to these members, it also counted mediators representing schools and management teams.

In its introduction, this document presents the intent of a dialog perspective with school communities. For that, “the collective writing of this text [DOCT-SL/RS of the city in the analysis] was performed with the participation of all city education network through six central schools of the city” (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 9). In this school group, although the invitation for participating in this writing task was made to the city’s state network and private schools in analysis, there was no participation of the state network. Through the collaboration regimen indicated at Art. 211 of the Federal Constitution of 1988 (BRASIL, 2016), in the National Education Guidelines and Bases Law (LDB), dated 1996 (BRASIL, 1996) and Brazilian National Education Plan (PNE) dated 2014 (BRASIL, 2014), the works of elaborating and implementing educational policies need to be articulated, coordinated, and institutionalized among federal entities (the Union, states, the Federal District, and cities), for ensuring the right to basic education, that is, all government spheres, not only specific educational networks or systems have the conjoint responsibility for attaining this end. However, what one verifies are simultaneous and disarticulated processes in which the state entity prioritized the re-elaboration of the curriculum of the Rio Grande do Sul State, named Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul (RCG), and the city entity prioritized the re-elaboration of the DOCT-SL/RS of its territory. This situation reveals a fragmented education that shall resonate negatively in the re-elaboration of Political-Teaching Projects of all educational networks and institutions that integrate the respective systems.

The state teaching network is not represented in the elaboration of the DOCT-SL/RS. It is also not represented in a relevant set of schools and institutions that compose the teaching system of the city under analysis. We also highlight that the absence of schools in the Rio Grande do Sul State, and only the presence of one school from the private teaching network may characterize a way of doing politics. By not conjointly participating in the production of the DOCT-SL/RS, the state education network highlights that it is not in compliance with the proposal of this document, in a clear rupture manifestation with the collaboration regimen proposal. Beyond party-political issues, we notice that underlying this action is the denial of more participatory educational policies among the federative entities, reproducing a centralizing, hierarchical, and vertical logic (Federal Government) in executing educational policies and demands. There is equal resistance by this network in collaborating on formulating a document administered by the education city network. To this extent, it is worth recalling Ball (1994, p. 20) on the relations between power and politics when affirming that power “is multifaceted, overlapping, interactive and complex, political texts enter instead of than simply changing power relations. Then, again, there is the complexity of the relationship between political intentions, texts, interpretations, and reactions.” In this sense, democratic education loses with this lack of involvement, participation, and integration between education systems and networks, mainly school communities.

Still, considering the DOCT-SL/RS, a public consultation was carried out concerning schools through a questionnaire hosted on the Moodle Platform7, most likely as a strategy due to the COVID-19 pandemic, mobilizing two thousand participants from all schools in the city education network, among which there were teachers, students, and those legally responsible for the students. Some private schools also sent their contributions. Subsequently, this document informs that,

[...] armed with suggestions made by management teams, the SMED constituted a group of thirty mediators for acting in the planning and mediation of constructing the Territorial Curriculum Document on June 10 of the present year. The group, composed of educators of the city, reunited twice before the specified date for training and planning actions. In the face of the study of materials elaborated by the UNCME, UNDIME, and ProBNCC movement. (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 12-13).

It is stated in the DOCT-SL/RS that, in August 2019, a Public Hearing took place for a “presentation and collection of suggestions from the community about this collective product [the São Leopoldo DOCT-SL/RS], before its writing and finalization by SMED” (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 10). This process highlights, again, the prominence of SMED at the conduction of production of this document and indicates that strategies of broadening the discussion through the city were employed. Regarding the elaboration of this document, we observe that a more broadened and democratic participation may have been jeopardized by the context of the pandemic and by the restrictive schedule of the ProBNCC. In any case, from the analysis performed, it is possible to consider that the principles of curricular justice and inclusion of the interests of the less favored, of participation, and the historical production of equality have hardly been achieved. The ways that the processes of elaboration of the BNCC, RCG, and DOCT-SL/RS took place, with only a few public consultations, that is, with minimal participation of society in general, especially of educators and other professionals that work in the education area, tends to reproduce resistance in schools.

Thus, putting into context the authors and actors who effectively produced the three curricular policies presented allows us to state that curricular policies in Brazil, in its times and movements, have been instituted from the interests of certain social groups, with distinct, concurrent, and concomitant processes and with no compliance with the collaboration regimen between the federative entities, which certainly ends up generating negative effects on school cultures and barriers to the involvement of school communities and educators (PRIESTLEY; BIESTA; ROBINSON, 2013, 2015) as curricular decision-makers (LEITE, 2002b; LEITE; FERNANDES, 2010). Indeed, the curricular policies, with low or restricted participation in its production process, have not recognized the decision power of the school and its actors in designing a curriculum. In this way, these policies distance themselves from achieving the principles of curricular justice in a school of all and for all, that is, in a school that fulfills the principle of equal opportunities for all social groups to whom education is intended (LEITE, 2002b, 2012; SAMPAIO; LEITE, 2017).

Nature of the Texts

The Brazilian National Core Curriculum is a 600-page document, approved on December 20, 2017, and structured into five chapters. In the first one, there are the foundations, legal frameworks, and implementation process of the BNCC; in the second, the structure of the BNCC; in the third, the details of the learning rights in the Childhood Education stage; and, in the fourth and fifth, in turn, the details of Elementary Education and High School in the context of basic education. The organic and progressive set of essential learnings that all students should develop throughout the stages and modes of basic education is normative, justified in the intention to granting that students are assured of their learning and development rights in compliance with what is established in the National Education Plan (BRASIL, 2014). This normative document applies exclusively to basic school education, as defined in paragraph 1 of Art. 1 of the National Education Guidelines and Bases Law, also known as Law no. 9.394/1996 (BRASIL, 1996), and refers to the ethical, political, and aesthetic principles aimed at the integral human formation and the construction of an equitable, democratic, and inclusive society, as grounded in the National Curricular Guidelines for Basic Education (DCN) (BRASIL, 2013).

As for the RCG, it is articulated the ten essential macro-competences of the BNCC and highlights that these should be developed throughout basic education, to grant cognitive, communicative, personal, and social learnings in a harmonious and interconnected manner, focusing on equity and surpassing inequalities of any nature. In addition, the RCG is structured in six pedagogical booklets: the first deals with Childhood Education, and the other five are organized by knowledge area — Languages, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, Human Sciences, and Religious Education. Throughout the booklets, the following parts are included: a presentation about the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul and the Collaboration Regimen; an introduction, which addresses how the proposed ideas were conceived; a first chapter of guiding principles of the RCG that explains the conceptions of education, learning, and training of subjects in the school context, the curriculum, the general competencies of the base, interdisciplinarity, comprehensive education, science and technology applied to the Education of the 21st century, and the assessment and ongoing teacher training; a second chapter, dealing with the educational modes (Special Education, Youth and Adult Education, Rural Education, Indigenous School Education, Education of Ethnic-Racial Relations, and Quilombola School Education); and the third chapter on contemporary issues. The other chapters of each booklet deal with specificities of Childhood Education, Languages, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, Human Sciences, and Religious Education.

DOCT-SL/RS, in turn, is an 87-page document and is structured throughout ten chapters. In its introduction, the first chapter, as stated before, the intention of preparing this document in dialog with school communities is expressed, and the limits that marked its effectiveness are presented. Another important aspect to note is that the term “territory,” present in the title, is absent in the body of this document. Thus, we infer that the concept of “territory” is founded on Art. 25 of RCG, which states the following:

The CEEd/RS and the UNCME/RS both recommend that each municipal territory, whether it has its system or not, can elaborate or review a local curricular document that contemplates its local and regional specificities, adding objectives and abilities to the diversified repartition, for implementation on a collaborative basis according to their City Education Plans. (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 17).

We note that, in the RCG document, “territory” is defined as “a space appropriated and transformed by human action, beyond the physical space - city, state, and union” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 17), indicating that this word is employed here with the notion of “ground” and “identity.” In the second chapter, in turn, the method is described, and in the third, the history of the city, which, according to this document, has 33 city schools for Childhood Education, 31 city schools for Elementary Education (which have Childhood Education classes), and 122 private schools, of which 41 are linked to SMED. The text of this third chapter, however, is summarized as it contains five paragraphs and does not present a reality-based diagnosis of the city’s education in analysis. Additionally, the composition of the City Education System was not described throughout the entirety of this document. As for the fourth chapter, the legal frameworks for education are presented, addressing the following: the Federal Constitution of 1988, the 1996 LDB, the 1997 National Curriculum Parameters, the 1998 National Curriculum Guidelines for Elementary School and High School, Resolution CNE/CEB no. 4/2010 and the specific guidelines for the nine-year Elementary School, Resolution CNE/CEB no. 7/2010, and the specific guidelines for High School, expressed in Resolution CNE/CEB no. 2/2012. All these documents indicate the need for creating a common national base, considering the National Education Plan and the City Education Plan.

The fifth chapter of the DOCT-SL/RS, in turn, addresses basic education and starts with a three-paragraph introduction based on the Federal Constitution and the LDB, in which basic education is described. It does not, however, make explicit the principles, guidelines, and concepts that guide the curriculum, which is presented with little evidence in the sections and chapters that deal with the stages and modes of education. Nevertheless, given the nature of this document, we consider that the production of a specific chapter or section referring to this content should have been included. Section 5.1 deals with Childhood Education, bringing a history of this education level in the city, the organization of age groups throughout Childhood Education, the conception of the child for Childhood Education, the conception of curriculum for Childhood Education, the rights of learning and the curricular design, taking into consideration the field of experience, the educators’ action, the follow-up on learning and the transition towards Elementary School. Moreover, we emphasize that the production of content related to Childhood Education is dense and articulated with the BNCC. Section 5.2, in turn, is dedicated to Elementary Schools from an in-context perspective anchored in legal rules, which includes the BNCC. Subsequently, it develops the following topics: teaching-learning, education as a learning right, and assessment. The subsequent section, still related to Elementary School, describes the subjects included in the educational process, highlighting the conception of the child, teenager, youngster, adult, and elder. We note, thus, that the educator is made invisible in this part of the DOCT-SL/RS.

The sixth chapter, consecutively, deals with High School, putting this educational stage in context through a quote by BNCC in two short paragraphs. In fact, High School is absent in the DOCT-SL/RS text, possibly because of the absence of the state network in its writing process, since, as previously mentioned, this educational stage was not part of the RCG, and because of the absence of participation of the private education network schools that serve High School in the municipality. Considering that this is a guiding text for the city territory, this absence weakens and reveals the incompletion of this document.

Specificities on the modes of school education are listed in the seventh chapter, based on the following themes: Youth and Adult Education, Full-Time Education, Special Education in the inclusive perspective, Rural Education, and Indigenous School Education. The eighth chapter, entitled “Cross-cutting educations,” presents cross-cutting, current themes, such as musical education, environment and sustainability education, human rights education, traffic education, food, and nutritional education, and financial education. Section 8.7 develops the theme of democratic management, having as a reference Law no. 6.134, dated December 20, 2006, and deals with democratic management in city public teaching. The ninth chapter, in turn, deals with the social quality of education, technology, and innovation, addressing, themes, research grants, quality in education, technology, and digital culture. Lastly, in the tenth chapter, the theme of ongoing formation for education professionals is treated, focusing on the following aspects related to the city network: democratic management, social quality of education, technology, and innovation; and ongoing formation.

In terms of content, we observe that the DOCT-SL/RS substantially describes the following topics: the process of its elaboration, the legal frameworks that sustain it, the subjects it wants to graduate, the transversal and integrating themes related to contemporary issues and required by legislation; and the specific norms that regulate the educational field. In this document, the lack of an educational diagnosis that is more detailed and deepened for the city under analysis is a factor that weakens the adherence to the concept of territory and the idea of an in-context curriculum (REIS, 2016). Moreover, we observe that the DOCT-SL/RS is fragile at the following contents that are contained in the proposed structure by the ProBNCC: educational history of the territory; discussion on competencies and abilities; considerations on the implementation of the curriculum; explanation of codes used; curricular organization (generally presented in charts); and forms of organization and grouping of abilities and/or knowledge objects (an aspect that is directly linked to the learnings that should be assured to students).

As for BNCC, we consider it a document with an excessively prescribing nature, detail-oriented and operational, which exceeds its nature as a national curriculum and “goes beyond parameters, guidelines, or mere guidelines” (BIONDO, 2019, p. 22). On the contrary, this document is restricted and limited to outlining guidelines and foundational concepts. The prescribing nature, the standardization, and the excess of instrumentation of BNCC may have provoked an effect of nearing curricula of state and city territories. We also reiterate the absence of representative entities in the BNCC drafting/writing process (specifically from the Rio Grande do Sul State and state and private network schools) and the importance of putting into context the curriculum that is prescribed at the national level (LEITE; FERNANDES; FIGUEIREDO, 2018, 2019).

VISITING KEY CONCEPTS IN THE FIELD OF CURRICULUM POLICIES

In this section, we analyze key concepts present in the documents under analysis, which are crucial in curriculum policy formulation, including education and school education; learning, essential learnings, and competence; curriculum, teaching, and assessment; and educator and student.

Education and School Education

Under the perspective of BNCC (BRASIL, 2017, p. 10), education “should affirm values and encourage actions that contribute to the transformation of society, making it more humane, socially fair.” It is also linked to the “rights and learning objectives, competencies, and abilities” (BRASIL, 2017, p. 14). It also appears as “global human formation and development” and a space for learning and inclusive democracy aimed at acceptance, recognition, and full development (BRASIL, 2017, p. 16). In the RCG (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 21), the conception of education is partially similar to the one presented by BNCC, presented as the “complete development of the subject.” It is also understood as “a public asset, a social right,” with “an emancipatory character” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 15-21). In the DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 40-41), in contrast, education is seen in a similar way as in the RCG, that is, as a “learning right” and a “full development of oneself”, a “social right and a living process”. In this sense, this notion of education is different from other conceptions because it highlights the social factor as an epistemological choice in the perspective of dialogical education, which is also freer, civilian, and focused on human rights. This way, it is possible to note that, throughout all three documents, the conceptions of education display similarity, nearer than those present in the RCG and the DOCT-SL/RS. In BNCC, there is a conception that is more centered on the subject, possessing, under certain perspectives, an individualistic approach, very different from the emphasis on the constant social commitment in the RCG and the DOCT-SL/RS.

Regarding the definition of school education, it is possible to note, both in the BNCC and in the RCG, a focus on student learning — despite such similarities, in the BNCC (BRASIL, 2017, p. 14), a certain legalistic and generalist aspect appears, even though it speaks of integral education as “an education aimed at their aimed at acceptance, recognition, and full development in their singularities and diversities.” As for the DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 39-40), there is a concept of “citizen education,” which “intends to form/educate with a focus on integrality” and that is committed to the “transformation of the reality of each human being,” and should, therefore, invest in the autonomy of students, empowering their development as “protagonist(s) of their history.” In this sense, this city document assumes the dialogical perspective of Paulo Freire’s thought, showing an emancipatory and freeing conception of education, capable of “promoting the transformation of subjects by stimulating the praxis (action and reflection) in a process of experimentation of its history” (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 7), thus opposing the logic of the state and federal documents.

Learning, Essential Learnings, and Competency

As for the concept of learning, we can note that, in the BNCC, there is no conceptual elaboration on the theme but only an association with the idea of quality and right. Learning networks and the school as a space of learning and inclusive democracy are emphasized, as well as the protagonist of the student in their learning and project of life. In the RCG (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 22-23), learning is put as the “result of the interaction between mental structures and the environment” and “as participation, mediation, and interactivity.” In the DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 23-36), learning is conceptualized as the student’s right and as an “ongoing process that involves the environment and the reality in which the student is inserted.” This subject is seen as “the knowledge construction process itself.” In this light, it is possible to note with more clarity, both in the RCG and in the DOCT-SL/RS, the focus on learning the subject of the student and their interactions.

As for essential learnings, they assume a very similar conception throughout the three documents, referencing competencies and abilities to be developed. Moreover, the word competence has the same conception in the BNCC and the RCG concerning the mobilization of knowledge, abilities, and behaviors. The DOCT-SL/RS does not present a definition of competence, but it mentions BNCC when it approaches the topic of Youth and Adult Education (EJA) and links this mode to the idea of essential learning.

Curriculum, Teaching, and Assessment

Curricular conception in the BNCC (BRASIL, 2017, p. 18) is related to “learnings that materialize as a set of decisions and that are in compliance with the interest of students and their identities.” In the RCG, the term appears to define various focuses, understood as “school experiences that unfold around knowledge, surrounded by social relations, and that contribute for the construction of the students’ identities,” as a set of “pedagogical efforts with educational intentions,” as a “device in which relations between society and the school, between socially constructed knowledge and practices, and school knowledge, concentrate,” and as “a set of knowledge that is articulated and normalized, defined by a certain order, in which meanings on the world are produced” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 26-27). DOCT-SL/RS, in turn, presents, with low emphasis and textual evidence, the definition of curriculum. As previously mentioned, the structuring concepts for guiding curricula in DOCT-SL/RS are within sections that especially deal with Childhood Education and Elementary School. However, it is noticeable the reference to a practice of flexible curricula and the prioritizing of the strategy of teaching through research (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021). Given these aspects, in compliance with Biondo (2019), we notice, in the BNCC, an instrumental conception of the curriculum. It is a policy of curricular homogenization focused on acting on different education components to reach the standardization it proposes.

Concerning the teaching conception, the BNCC mentions it as competencies and the action of “creating and making available guidance materials for educators, as well as maintaining permanent formation processes” (BRASIL, 2017, p. 15). RCG, in turn, mentions teaching that focuses “its actions in the search for meaningful learning, paying attention to the different life experiences of each person” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, p. 23). Differently from these two conceptions, which have as their centrality the teaching by and for competencies and meaningful learning, the DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 38) states that the “center of the teaching-learning process is shifted from contents to subjects,” showing the “Education through research as one of the possibilities of knowledge construction.”

Regarding assessment, the BNCC (BRASIL, 2017, p. 19) focuses on large-scale assessments as “formative procedures of process or outcome.” The RCG conception is distinct, as it sees assessment “as something inherent to everyday and learning processes, in which all subjects are involved,” whose focus consists of “providing information about learning actions, it [the assessment] concerns the construction of autonomy on the part of the student, to the extent that they are asked to play an active role in their learning process” (RIO GRANDE DO SUL, 2018, 2018, p. 32-34). The DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 41) explains the assessment as an “ongoing, diagnostic, horizontal, and procedural process,” stating that the assessment processes must “consider the different dimensions of the subject, using different methods,” and that the “assessment must be synchronized with the rights and goals of reflective, humanizing, and contextualized learning.”

Educator and Student

The definition of educator and student is not clearly stated in the BNCC since these terms appear only once when related to Childhood Education. In the RCT, the educator is defined as a mediator, but there is no reference to the definition of a student. In the DOCT-SL/RS (SÃO LEOPOLDO, 2021, p. 40), the educator is understood as a “main reference through the learning process,” and the student is the “protagonist of their own story.” We also note that both the BNCC and the DOCT-SL/RS highlight the student as the subject of learning. However, the DOCT-SL/RS goes further, explaining that the student has more than a central role, a protagonist with autonomy and participation in the school project. This definition contemplates the proposal of a more dialogical education defended by Paulo Freire and assumed as epistemological, theoretical, and methodological referential in the city document.

It is equally important to emphasize that these official documents may have limited power in the curricular and pedagogical practices put into practice by schools, which, for multiple reasons, resist and re-signify educational policies (BALL; MAGUIRE; BRAUN, 2016). Examining the contents of the texts and what they announce in terms of concepts and curricular practices, it is possible to state that these practices occur instituted by distinct political and temporal processes and may not represent the school cultures and the educators’ power of agency (PRIESTLEY; BIESTA; ROBINSON, 2013, 2015; SANTOS; LEITE, 2020). However, we understand that, in school contexts, it is fundamental that managers, experts, and educators play a role as curricular decision-makers (LEITE, 2002b; LEITE, FERNANDES, 2010; LEITE; FERNANDES; FIGUEIREDO, 2018, 2019).

Even though we identified in the text of the DOCT-SL/RS, especially concerning Childhood Education, the incorporation of concepts from a perspective that is more aligned to democratic education, it does not mean that such perspective is implemented in the schools and into the curricular practices: it is necessary to consider that it is in practice that conflicts, setbacks, and advances, are unveiled (BACHELARD, 1996). Additionally, from the reading of the DOCT-SL/RS, it is possible to note the necessity of development on the construction of this document’s identity as for advances, limits, and possibilities in the collaborative formation process, prioritizing the formation of educators and managers, which does not exclude other actors encompassed by the school community.

In the Brazilian educational context, surrounded by the scenario of changing political ideologies and national, state, and city powers, especially after 2016, when we had a coup in our institutional democracy, we are going backward as for efforts and fights for more democratic and inclusive educational policies that provide learnings of social quality for everyone and that relate with the conception of a school with more autonomy and that has intelligent curricula (LEITE, 2003). We live through an immeasurable setback, with governments and powers that blend the shades and characteristics of despotism, authoritarianism, arbitrariness, conservatism, and dogmatism. Thus, public education as a subjective social right for all people, which has social quality and is financed by the State in the perspective of a democratic education guided by social and curricular justice, is clearly at risk (CONNELL, 1999, 2012; DUBET, 1996, 2008, 2011; SANTOMÉ, 2013; SAMPAIO; LEITE, 2017).

FINAL REMARKS

As previously mentioned during the presentation of this article, it covers a study focused on Brazilian curricular policies and aimed at bringing to academic debate the characteristics of documents that announce said policies and the modes they point to these procedures that align with democratic education. Data from the document analysis revealed that guidelines of democratic education, namely what implies the participation of civil society and school communities in the production of curricula policies, are, overall, restricted to some representations and public consultancies. As shown, the Brazilian National Core Curriculum (BNCC) as a macro strategy constitutes a document that has an excessively prescribing and operational nature, produced by a restricted group of actors. This document is restricted and limited to outlining guidelines for its unfolding at state and city levels, with broad participation and involvement of school communities. In any case, it is possible, when reading the Curricular Referential of Rio Grande do Sul (RCG), to infer a pedagogical proposal centered on the development of competencies, which has a greater conceptual expression in the BNCC than in the Curricular Guiding Document of the São Leopoldo/RS Territory (DOCT-SL/RS).

Moreover, we identified aspects that are not in compliance with the collaboration regimen for elaborating and producing analyzed texts, highlighting the lack of articulation between state and city processes, with emphasis on the lack of participation of both federal entities and other actors that represent civil society and school communities. In the DOCT-SL/RS, we found signs of efforts for broadening this participation through representativity and feedback of a public consultation to schools, therefore mobilizing educators, managers, and different educational entities in the city and thus demonstrating a strong dialogical purpose. Even so, one may infer that the DOCT-SL/RS did not reach its proposal of encompassing the territory as announced by this document in its introductory section, given that it is more limited to the city network of education, as, besides effort, it did not obtain the collaboration of other teaching networks.

Lastly, we highlight that the BNCC, as a guiding national curriculum for the re-elaboration of curricula policies of the systems, networks, and school institutions throughout the country, is based on a conception of the development of competences of an instrumental and normalizing nature, coherent with the interests of agents and private company institutions that strongly acted in the production of this document and is far from the proposal of democratic education. These findings reveal the necessity of academic communities to continue to concoct measures of re-inserting context into curricula capable of solidifying the processes of a more democratic education that leaves no one behind.

REFERENCES

AVELAR, Marina; BALL, Stephen. Mapping new philanthropy and the heterarchical state: the mobilization for the national learning standards in Brazil. International Journal of Educational Development, v. 64, p. 65-73, Jan. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.09.007. [ Links ]

BACHELARD, Gaston. A formação do espírito científico: contribuição para uma psicanálise do conhecimento. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto, 1996. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen. Education reform: a critical and post-structural approach. London: Open University Press, 1994. [ Links ]

BALL, Stephen; MAGUIRE, Meg; BRAUN, Annette. Como as escolas fazem as políticas: atuação em escolas secundárias. Ponta Grossa: UEPG, 2016. [ Links ]

BIONDO, Franco Gomes. Base Nacional Comum Curricular: contexto, significados e desalinhamentos cotidianos. E-Mosaicos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 8, n. 17, p. 19-33, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.e-publicacoes.uerj.br/index.php/e-mosaicos/article/view/38729/29674 . Acesso em: > 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRANCO, Alessandra Batista de Godoi et al. Urgência da reforma do ensino médio e emergência da BNCC. Revista Contemporânea de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 14, n. 29, p. 345-363, 2019. Disponível em:https://revistas.ufrj.br/index.php/rce/article/view/22187. Acesso em:15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. [Constituição (1988)]. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil: texto constitucional promulgado em 5 de outubro de 1988, com as alterações determinadas pelas Emendas Constitucionais de Revisão nos 1 a 6/94, pelas Emendas Constitucionais nos 1/92 a 91/2016 e pelo Decreto Legislativo no 186/2008. - Brasília: Senado Federal, Coordenação de Edições Técnicas, 2016. 496p. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/518231/CF88_Livro_EC91_2016.pdf . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, 1996. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394compilado.htm . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação.. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão. Secretaria de Educação Profissional e Tecnológica. Conselho Nacional da Educação. Câmara Nacional de Educação Básica. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais Gerais da Educação Básica. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Diretoria de Currículos e Educação Integral. Brasília: MEC, SEB, DICEI, 2013. 562p. ISBN: 978-857783-136-4. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=13448-diretrizes-curiculares-nacionais-2013-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação.. Plano Nacional de Educação 2014. Brasília: STIC-MEC, 2014. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://pne.mec.gov.br . Acesso em: > 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação.. Base nacional comum curricular. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2017. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_EI_EF_110518_versaofinal_site.pdf . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação.. Portaria nº 331, de 5 de abril de 2018. Institui o Programa de Apoio à Implementação da Base Nacional Comum Curricular - ProBNCC e estabelece diretrizes, parâmetros e critérios para sua implementação. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, n. 66, p. 10, 6 abr. 2018. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/historico/PORTARIA331DE5 DEABRILDE2018.pdf . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria nº 756, de 03 de abril de 2019. Altera a Portaria nº 331, de 5 de abril de 2018, que institui o Programa de Apoio à Implementação da Base Nacional Comum Curricular - ProBNCC. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF , n. 65, p. 27, 4 abr. 2019. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.in.gov.br/materia/-/asset_publisher/Kujrw0TZC2Mb/content/id/70004945/do1-2019-04-04-portaria-n-756-de-3-de-abril-de-2019-70004722 . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

CELLARD, André. A análise documental. In: POUPART, Jean et al. A pesquisa qualitativa: enfoques epistemológicos e metodológicos. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012. p. 295-316. [ Links ]

CONNELL, Raewyn. Estabelecendo a diferença: escolas, famílias e divisão social. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1995. [ Links ]

CONNELL, Raewyn. Escuelas e justicia social. Madrid: Ediciones Morata, 1999. [ Links ]

CONNELL, Raewyn. Just education. Journal of Education Policy, v. 27, n. 5, p. 681-683, Sept. 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.710022. [ Links ]

CONSELHO ESTADUAL DE EDUCAÇÃO(Rio Grande do Sul). Resolução nº 345/2018. Institui e orienta a implementação do Referencial Curricular Gaúcho - RCG, elaborado em Regime de Colaboração, a ser respeitado obrigatoriamente ao longo das etapas, e respectivas modalidades, da Educação Infantil e do Ensino Fundamental, que embasa o currículo das unidades escolares, no território estadual. Rio Grande do Sul: Secretaria da Educação, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.ceed.rs.gov.br/resolucao-n-0345-2018. Acesso em:15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

CORTESÃO, Luiza. Teachers and ‘resting routines’: reflections on cognitive justice, inclusion and the pedagogy of poverty. Improving Schools, v. 14, n. 3, p. 258-267, Nov. 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480211422284. [ Links ]

COSTA, Hugo Heleno Camilo; LOPES, Alice Casimiro. A contextualização do conhecimento no ensino médio: tentativas de controle do outro. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 39, n. 143, p. 301-320, abr./jun. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302018184558. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. Sociologia da experiência. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 1996. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. O que é uma escola justa? A escola de oportunidades. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. Mutações cruzadas: a cidadania e a cidadania. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 16, n. 47, p. 289-305, ago. 2011. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782011000200002. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Florestan. A revolução burguesa no Brasil. Ensaio de interpretação sociológica. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1976. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Preciosa. O currículo do ensino básico em Portugal - políticas, perspectivas e desafios. Porto: Porto Editora, 2012. [ Links ]

FERRAÇO, Carlos Eduardo; CARVALHO, Janete Magalhães. Currículo, cotidiano e conversações. Revista e-Curriculum, São Paulo, v. 8, n. 2, ago. 2012. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/curriculum/article/view/10985/8105 . Acesso em: 15 set 2021. [ Links ]

FERRETI, Celso João; SILVA, Monica Ribeiro da. Reforma do Ensino Médio no contexto da medida provisória n. 746/2016: estado, currículo e disputas por hegemonia. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 385-404, abr./jun. 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302017176607. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Ação cultural para a liberdade. 5. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1981. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Educação como prática de liberdade. 25. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra , 2001. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Extensão ou comunicação? Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra , 2002. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra , 2005. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Fabrício Monte; SILVA, João Alberto da; LEITE, Maria Cecília Lorea. Diretrizes invisíveis e regras distributivas nas políticas curriculares da nova BNCC. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 18, n. 3, p. 857-870, 2018. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.curriculosemfronteiras.org/vol18iss3articles/freitas-silva-leite.pdf . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

FREIXO, Adriano de; RODRIGUES, Thiago. Introdução: sobre crises e golpes ou uma explicação para Alice. In: FREIXO, Adriano de; RODRIGUES, Thiago (org.). 2016, o ano do Golpe. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina Raquel, 2016. p. 9-17. [ Links ]

FUJITA, Mariângela Spotti Lopes. A representação documentária de artigos científicos em educação especial: orientação aos autores para determinação de palavras-chave. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, v. 10, n. 3, p. 257-272, set./dez. 2004. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://educa.fcc.org.br/pdf/rbee/v10n03/v10n03a02.pdf . Acesso em: 15 set. 2021. [ Links ]

GIROTTO, Eduardo Donizeti. Pode a política pública mentir? A Base Nacional Comum Curricular e a disputa da qualidade educacional. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 40, set. 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302019207906. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry. La escuela y la lucha por la ciudadanía. Madrid: Siglo Veintuno Editores, 1993. [ Links ]