Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.37 Curitiba 2021 Epub 06-Set-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.77098

DOSSIER - Environmental Education and Elementary and Secondary School: contexts and practices

Education for Ethnic-Racial Relations and the training of History teachers in the new guidelines for teacher training!1

( Universidade Federal do Pará. Belém, Pará, Brasil. E-mail: mauroccoelho@yahoo.com.br - E-mail: wilmacoelho@yahoo.com.br

In the present paper, we analyze one of the aspects of the projected educational policy - the Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica [National Curriculum Guidelines for the Initial Teachers Training for Basic Education] approved in 2019 by the Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE) [National Education Council] - arguing how it directs education to ethnic-racial relations, taking History degrees as a parameter. Since the proposed guidelines do not cancel out the educational policy of an affirmative character, it is relevant to put into perspective how the design thought for the initial teacher training promotes teaching knowledge that enables the teacher to face racism and its consequences. We maintain that the recently approved guidelines by the CNE lead to a restrictive formation concerning Education for Ethnic-Racial Relations because they restrict the space of teaching autonomy and the contact with the necessary knowledge to face racism and its consequences in the school space. Also, the guidelines deepen recurring deficiencies in history teacher training courses, thus creating little room for discussing topics such as Difference, Diversity, Multiculturalism, Inclusion, etc.

Keywords: Teacher Training; Teaching of History; Ethnic-Racial Relationships; Curriculum

No presente artigo, analisamos um dos aspectos da política educacional projetada - as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica aprovadas em 2019, pelo Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE) - problematizando o modo pelo qual ela encaminha a educação para a as relações étnico-raciais, tendo como parâmetro as licenciaturas em História. Uma vez que as diretrizes propostas não anulam a política educacional de caráter afirmativo, torna-se relevante dimensionar o modo pelo qual o desenho pensado para a formação inicial promove saberes docentes que capacitem o professor para o enfrentamento do racismo e de seus desdobramentos. Sustentamos que as diretrizes recentemente aprovadas pelo CNE encaminham uma formação restritiva, no tocante à Educação para as Relações Étnico-Raciais, posto limitarem o espaço da autonomia docente e o contato com saberes necessários ao enfrentamento do racismo e de seus desdobramentos no espaço escolar. Ademais, as diretrizes aprofundam deficiências recorrentes nos cursos de formação de professores de história, tornando ainda mais rarefeito o espaço para a discussão de temas como Diferença, Diversidade, Multiculturalismo, Inclusão etc.

Palavras-chave: Formação Docente; Ensino em História; Relações Étnico-Raciais; Currículo

The last few years have witnessed an unprecedented movement in the trajectory of Education in Brazil: the attempt to profile educational policies, to guarantee the alignment of Basic Education and Higher Education curricula (concerning teacher training processes), of processes of production and evaluation of didactic resources (exceptionally textbooks distributed by the Programa Nacional do Livro Didático - PNLD [National Textbook Program] and evaluation procedures (both large-scale, focused on Basic Education, and those related to undergraduate courses of teacher training). Through such policies, a national education system takes shape: a set of entities, policies, instruments and agents articulated, coherently, promoting what Basic Education should be2.

We highlight three pieces of evidences of this movement: The Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC) [National Common Curricular Base] formulation, the reorientation of PNLD public notices, and the promulgation of new national curricular guidelines for teacher training. They are linked from the BNCC, and they assume the reformulation and implementation of the average curriculum as the basic education panacea as if once implemented, school failure and inequalities between students in private and public schools would disappear.

In this paper, we intend to analyze one of the aspects of the projected educational policy - the Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica [National Curriculum Guidelines for the Initial Teachers Training for Basic Education], formulated by the Conselho Nacional de Educação - CNE (BRASIL, 2019b) [National Education Council]- questioning how it forwards Education to Ethnic-Racial Relations (ERER), taking History degrees courses as a parameter. Since the proposed guidelines do not nullify the affirmative educational policy (BRASIL, 1996, 2003, 2004a, 2008, 2015), it is relevant to dimension how the initial training promotes teaching knowledge that enables teachers to face racism and its consequences.

We then work with the following sets of documents: the guidelines for teacher training approved by the CNE since the beginning of the century - considering the resolutions and technical and legal opinions that support them; educational legislation, with emphasis on affirmative legislation; and 47 curricula of history teacher training, offered by public institutions3. The 47 curricula analyzed in this paper were raised from consultation with the Cadastro Nacional de Cursos e Instituições de Educação Superior e-MEC [National Register of Courses and Higher Education Institutions e-MEC] (BRASIL, 2020).

The sources were analyzed from the curriculum concept (GOODSON, 1995; SILVA, 1999). Thus, the sources were perceived as expressions of tensions around the subjects, how to teach them and what kind of teacher is expected. In the same way, we distinguish between prescribed curriculum and curriculum in action, so that what we analyze next is the projection of teacher training based on the source’s information. We also work with the discourse concept, considering the different texts enunciated in a broader dialogue, whose context gives meaning to the positions taken (BAKHTIN, 1988). For data categorization, we used content analysis (BARDIN, 2016).

The paper has two parts. In the first one, we situate how the degree courses in history go, considering their structure and the place occupied by the subjects focused on Education for Ethnic-Racial Relations. In the second, we argue the impact of the proposed guidelines for the history teachers training and how those guidelines dimension the knowledge necessary for anti-racist education.

History teachers training and Education for Ethnic-Racial Relations

The history teacher training takes part in the tradition of higher education for teacher training in Brazil. The teacher training in Brazil was conceived as a bachelor’s degree appendix. Concerning the history teacher training, it had historiographical knowledge as an axis which promoted the researcher training, regardless of teaching issues (CERRI, 2013). The finding is old, and the sources supporting it feed contemporary criticism.

Much of the history teachers’ training focuses on the same problems pointed out decades ago. They start from the premise that historiographic knowledge is sufficient to face the challenges and demands of school history. For no other reason, the historiographic subjects make up the curriculum backbone and cultivate little space for reflections that compare historiographic and teaching knowledge (CAIMI, 2006; FERREIRA; FRANCO, 2008; CAVALCANTI, 2018). Thus thought, the history teachers’ training relegates to the second plan the discussions about two factors essential to the effectiveness of History as relevant disciplinary knowledge in Basic Education: the specificity of historical school knowledge and the context of Brazilian education and the public served by it.

In a previous reflection, we pointed out the small space that discussions around teaching and Education for Ethnic-Racial Relations occupied in ten curriculum pathways to history teacher training (COELHO, M.; COELHO, W., 2018). Here, we expanded the universe of institutions and presented the partial data of ongoing research. We consider 47 curricular pathways for history teachers’ training to understand how they are structured and how they deal with racism and its consequences. However, before approaching the data, let us account what is conveyed by the guidelines built within the scope of affirmative policies.

The Laws nº 10,639/2003 (BRASIL, 2003) and nº 11,645/2008 (BRASIL, 2008) make up a legal apparatus that reorients the curriculum and the approach to Brazilian history in Brazilian education. Less than introducing content related to the History of Africa, Afro-Brazilian Culture, and the History of Indigenous Peoples, they postulate a reformulation of how the History of Brazil is perceived. Engineered from social movements, especially black and indigenous, the legislation demands a Eurocentric perspective critique and the recognition of the propositional action of Africans, Indigenous, and Blacks in the processes that shape the Brazilian historical trajectory.

As we have already pointed out in other papers, its implementation implies a change in perspectives that inform the school's historical narrative and Brazilian historiography since its formation in the 19th century (COELHO, W.; COELHO, M., 2013). The national historiographical production was constituted disregarding significant portions of the Brazilian people - black, indigenous, poor, women - conforming to what was conventionally called the exclusion paradigm (CHALHOUB; SILVA, 2009). A narrative marked by the centrality of Europe (assumed as the history of the world epicenter and the genesis of Brazilian history) was consolidated, based on single action of great characters - white, as a rule - in events in which the elites defined the paths of Brazilian life.

This orientation critiques demand more than the inclusion of contents. It requires criticism of Eurocentrism, the inclusion of other characters in the historical narratives, and the valorization of the historical events in which Africans, Indigenous, and Blacks have had effective participation. However, it is not only for the past that legislation turns. Committed to combating racism and promoting anti-racist education, its implementation also requires reflection on racism and its consequences on how it is instituted in the school space, how it affects children and adolescents and how to fight it. Well, both demands of the legislation are absent from the history teacher training curriculum.

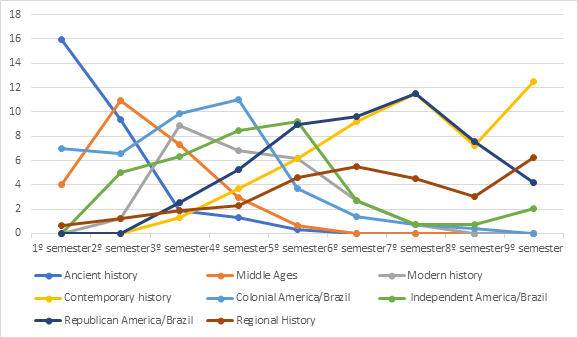

The data collected shows that the history teachers’ training is organized around a sequential and linear narrative that assumes the European trajectory as the space that moves History. Europe is introduced as the processes focus that reach and create other spaces - such as Africa, Asia, and America. The 47 curricular pathways for history teachers’ training are structured in semesters. The training was offered in about nine semesters. Let us see, then, the distribution of disciplines and their themes by semesters, as shown in the graph below:

The chart points out the peaks of incidence of historiographic subjects (those whose menus address historiographical knowledge) through spatial and temporal cuts. As the quadripartite model is universal, in the spectrum of analyzed routes, we identified the subjects that deal with Antiquity and the Middle, Modern, and Contemporary ages. Likewise, Brazilian and American history subjects are divided by temporal approaches - colonial, independent, and republican. In many curricular pathways, there are subjects aimed at dealing with regional issues, so we also identify them.

The chart shows the semesters with the highest incidence of records of the historiographic subjects through their spatial and temporal cutouts, considering the quadripartite model and subject identification focused on Brazilian history, American history, and Regional history. The peaks point to recurrences in most of the 47 curricular pathways for history teachers’ training. As can be seen, the study of Ancient history coincides with the beginning of the curricular paths. As a rule, future teachers begin their contact with the historiographic discourse through the treatment of Antiquity. The Middle Ages history is addressed in the second semester of training. The European Modern history is inserted in the third semester when it finds the American and Brazilian history. The European Contemporary history is introduced in the fifth semester, concomitantly with the American emancipation. Regional History has no expression until the end of the analyzed routes.

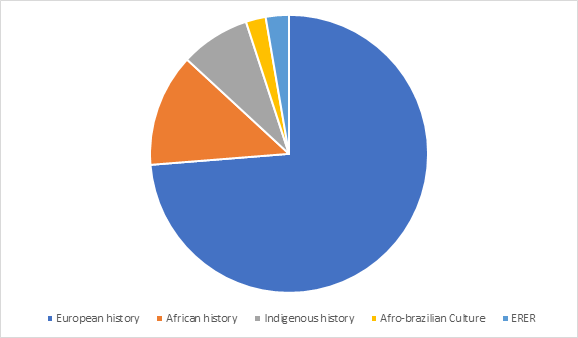

The linear, chronological sequence does not suggest the incorporation of the criticism sent by the legislation. What is happening in the incorporation of subjects occupied with the African and Indigenous history, unrelated to the narrative consecrated by tradition. According to a previous study, those subjects are more about Europe and its achievements in Africa and America than the way African and Indigenous peoples have known other dynamics not generated since Europe (COELHO, M.; COELHO, W., 2018). Furthermore, the volume of subjects concerned with Europe compares to those which focus on African or Indigenous peoples - even if it is as objects of European interest - is evidence of the mismatch with the legislation aimed at combating racism, as shown in the graph below.

As can be seen, the contrast between the volumes of subjects is significant. However, the approach is more eloquent than the difference showing in the chart above: even in the subjects occupied with the themes foreseen by the legislation, Europe is perceived as the historical process’s epicenter. Also, discussions about tackling racism in the school environment, expressed in dealing with the guidelines for ERER, are only present in 14 subjects distributed over 47 curricular pathways. Meanwhile, we have listed more than 60 subjects occupied with the medieval world until now...

Coping with racism and its consequences is not only done with the reformulation of curricular matrices. The discussion on teaching, learning processes, didactic-pedagogical approaches aimed at addressing sensitive issues - such as racism - and how it affects children and adolescents and their relationship with the world (and the School, especially) are fundamental for the demands of civil society to be carried out. Let us see then how the history teachers’ training in the study gives attention to didactic-pedagogical knowledge.

We return to the assumption made by Flávia Caimi, according to which to teach history it is necessary to three dimensions into account - the historical knowledge, the teaching and learning processes, and the history students in Basic Education (CAIMI, 2009). Caimi's reflection relevance consists of a synthesis construction that encompasses teaching knowledge, which is not linked in importance order but rather of necessity. What is taught, how it is taught, and for whom it is taught are factors whose expression depends on others - especially on the student who learns, on what he or she can, needs, or should learn, on how someone can teach and promote learning, considering the student's age and his socioeconomic conditions, cultural and academic background and, finally, the social environment in which the student is inserted, etc.

Flávia Caimi's consideration is also consistent with reflections on the specificity of school history knowledge (MONTEIRO, 2007) and discussions about learning in history - regardless of the perspective from which one starts (RIBEIRO; RIBEIRO JÚNIOR; VALÉRIO, 2016). The history taught at the school is the result of specific construction, committed to the objectives of the formal education and permeated by the school culture. It is the result of an operation that articulates historiographic knowledge, pedagogical didactic knowledge, curriculum demands, the teacher’s experience, among other factors. Discussions around learning in history have been considering the cognitive processes that contribute to the understanding of historical knowledge, with the epistemology of the subject or theories of child and adolescent learning as the horizon.

Then, we identified the three dimensions of teaching knowledge in teacher training in history. As this is ongoing research, the data are not conclusive and indicate the analysis stages. However, they confirm data consolidated in the previous investigation and other studies about teacher training.

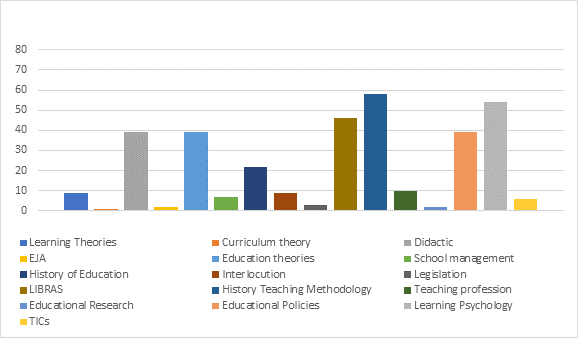

The chart above brings together the didactic-pedagogical training subjects of the 47 curricular pathways for teachers training in history. We bring them together in categories in order to give their scope account: (a) Learning theories - assessing learning processes; (b) Curriculum theory - curriculum theories discussion; (c) Didactic - General Didactics studies; (d) Educação de Jovens e Adultos (EJA) [Youth and Adult Education] - this level of education specificity; (e) Education theories - principles of Education, considering perspectives of philosophy, sociology and educational studies; (f) School management - educational management; (g) History of Education - trajectory of Education; (h) Interlocution - the interface between History and Education; (i) Legislation - educational legislation; (j) LIBRAS - fundamentals of the Brazilian Sign Language; (l) History Teaching Methodology - didactic guidelines required by history in Basic Education; (m) Teaching profession - the teaching profession aspects; (n) Educational Research - education research theoretical and methodological issues; (o) Educational Policies - educational projects and policies in Brazil; (p) Learning Psychology - learning theories; (q) TICs - Tecnologias da Informação e Comunicação [Information and Communication Technologies] - for educational purposes.

The chart points out that only subjects focused on the methodology of history teaching and learning psychologies are common to all curriculum pathways. The two cases have at least 47 incidences, a number equivalent to the curricular paths surveyed. It is noteworthy that subjects that operate the dialogue between teaching knowledge are an exception - we found only nine incidences in the 47 analyzed directions, pointing out how the history teacher training takes place.

Next, we consider the knowledge about the Basic Education students. The curriculum pathways under study point out two subjects concerned with the student - the teaching of Brazilian Sign Language and learning theories. The LIBRAS and Learning Psychology subjects are sovereign - and exclusive - in dealing with this dimension of teaching knowledge. The socioeconomic context of the students, the researches on adolescence and youth - especially on youth culture - and the way they relate to School are not part of concern in curriculum pathways repertoire.

Then, didactic-pedagogical knowledge. As a rule, the 47 curricula pathways offer fundamentals of Education subjects - philosophy and/or sociology of Education - and the School structure and the organization of the educational system - management, legislation, educational policies, and Basic Education stages. Teaching elementary issues, such as discussions about the curriculum and the profession, are rarely addressed. Even the education history is not offered in more than half of the curriculum pathways under study. It should also be noted that there is little space for educational research and for dealing with the world wide web - an omnipresent instance in today's life and a recurring resource in the daily lives of adolescents and young people.

About historical knowledge, it appears that the curricular paths assume the teacher's work as an instrumental operation. In most of the curricular paths, there are subjects about how history should be taught - subjects on specific didactics and methodologies for teaching history, along with the General Didactics subjects. As a rule, we are referring to a single subject focused on the processes of transforming historiographic knowledge into school knowledge.

The curricular paths under study allow the validation of some conclusions. Firstly, the limited space for the historical school narrative in undergraduate degrees in history. How Africans, Indians, and Black’s exclude tradition from the processes that make the Brazilian trajectory as a country and as a nation does not form a structural discussion in most of the analyzed curriculum paths. Secondly, the analysis of the teaching knowledge these pathways suggests that an understanding that the history teacher's job is to translate historiographic knowledge for children, adolescents, and adults in Basic Education is recurrent. Third, the paths show that there are no discussions about the students, considering their socioeconomic and historical contexts. Fourthly, the teacher training offered does not give the necessary attention to the fight against Racism, whether we consider the narrative guided by the sequence of historiographic subjects and by the approaches present in the subjects focused on the studies of Africa, Afro-Brazilian Culture and Indigenous Peoples, either let us take into account the place (or its absence) of discussions about Racism and the way it expresses itself in school culture.

The unable abilities: the (in)difference in the new curriculum guidelines of teacher training

The Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação das Relações Étnico-Raciais (DCNERER) [National Curriculum Guidelines for the Education of Ethnic-Racial Relations] assumes the dealing with Racism and the promotion of Difference and Diversity comprises more than the mastery of contents. Scientific knowledge about social relations, identities construction processes, and the recurrent Brazilian society social hierarchy (and its consequences) is necessary. In addition to it, teachers must conduct didactic-pedagogical processes that discuss the ethnic-racial categories present in Brazilian society, problematize and expose racism, criticize the traditional narratives about our formation, and recognize the different ethnic-racial belongings. Such issues demand commitment - with the fight against racism, learning processes that engender inclusion, and the Diversity recognition as a positive factor (BRASIL, 2004b).

The general and specific competency profile that teachers should develop in their initial training, according to the new guidelines for teacher training, disregard the instructions formulated by the same council for dealing with ethnic-racial relations in the School. None of them recognizes Racism as a structuring factor in the relationships built up in the school environment, nor do they take into account its consequences in the teacher training offered, either in the perpetuation of values that reiterate the social hierarchies based on color or in the impact that it has on the children and adolescent’s identity confirmation.

In this sense, the new guidelines disable one of the principles of Basic Education, as it is established in the Brazilian Constitution and the Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional (LDBEN) [National Education Guidelines and Framework Law]:

Education, which is the right of all and duty of the State and of the family, shall be promoted and fostered with the cooperation of society, with a view to the full development of the person, his preparation for the exercise of citizenship and his qualification for work. (BRASIL, 1988, our translation, our emphasis).

Basic Education aims to develop the student, provide him with the necessary common training for the exercise of citizenship and provide him with the means to progress in work and further studies (BRASIL, 1996, our translation, our emphasis).

The full personal development and the preparation for citizenship exercise require the appropriation of values that give rise to the principles of equality, coexistence, and respect for differences. Regarding Racism, the disregard of its specificities and its scope contribute to its reproduction and strengthening in school culture.

The ERER participates in the person formation, the citizenship exercise preparation, and affects the world of work. Racism and its consequences affect individual identities, access to public goods and insertion in labor market (FERREIRA; CAMARGO, 2011; SILVÉRIO; TRINIDAD, 2012; MACHADO JÚNIOR; BAZANINI; MONTAVANI, 2018; ANUNCIAÇÃO; TRAD; FERREIRA, 2020). Therefore, dealing with racism requires specific didactic-pedagogical approaches, as proposed by the DCNERER.

It happens that the abilities to be developed by the undergraduates, according to the new teacher training guidelines, suggest the opposite. To this end, the guidelines adopt the concept of competencies profile, as the BNCC gives meaning to it (BRASIL, 2017). The guidelines emphasize the importance of socio-emotional competencies profile in the education of children, adolescents, and adults since they consist of “individual capacities that manifest themselves consistently in patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors” (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 12). To promote them, future teachers should develop other skills, in addition to those provided by the BNCC.

The teaching competencies profile would be those provided by the BNCC for Basic Education and others specific to the teaching profession. These others are brought together in three dimensions: professional knowledge, professional practice, and professional engagement. Professional knowledge comprises “the acquisition of knowledge that gives meaning and meaning to a professional practice carried out at school” (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 16) - such knowledge is related to the curricular contents and what should be done with them. Thus, professional practice is a relevant factor in the processes of teacher training. Pedagogical knowledge - “pedagogical knowledge of the content, that is, the way these are worked in the classroom” (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 16) - is therefore valued. Professional engagement is understood as an ethical and moral commitment to oneself, the student, and the school community (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 17).

The guidelines refer to ten general teaching competencies profiles (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 17). They are accompanied by twelve specific competencies related to the three dimensions mentioned above (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 17-18). The exact competencies are related to 62 abilities, which will be resumed in the last part of this article. In addition to competencies and qualification, the guidelines forward some pedagogical foundations to teacher training: (a) deepening of reading competence and mastery of the Portuguese Language norms; (b) innovative methodologies aligned with the BNCC mastery; (c) link between teaching and research, focusing on teaching and learning processes; (d) use of digital languages for the development of abilities related to what the BNCC provides; (e) training process ongoing evaluation; (f) teaching work management; (g) assumption of the School as teacher training institution; (h) attention to the integral training of teachers, comprising competencies profile, abilities, and values; (i) ability to make data-based decisions (BRASIL, 2019a, p. 22).

Teacher training should then develop general abilities related to three dimensions - professional knowledge, professional practice, and professional engagement. Each of these dimensions is accompanied by specific competencies and capabilities. Knowledge-related competencies have 21 linked abilities. Those related to practice make up 22 abilities. Those concerning engagement comprise 19 abilities. Let us consider them.

Professional knowledge abilities concern four dimensions: the knowledge objects, students and how they learn, and educational systems. Concerning the first dimension, they provide for the apprehension of knowledge objects, especially (but not only) those provided for by the BNCC. They do not advance in curriculum components epistemology reflection and on the theoretical clashes that affect the production of school historical knowledge. The abilities, in this case, focus on memorizing the contents and not their conceptual mastery. Regarding the second, they translate assumptions to be considered in teaching strategies formulation and the students' socioeconomic situation recognition. They do not lead to reflections on the cognitive processes demanded by disciplinary knowledge, nor on how students' socioeconomic conditions and cultural background affect teaching and learning processes. The same happens with the mastery of educational systems - they need to be recognized by undergraduates.

Skills linked to professional practice are associated with four other dimensions: planning, management, assessment, teaching, and learning processes operation. The new guidelines assume that teachers must be able to plan activities following the provisions of the BNCC and promote learning situations. Again, there are no considerations on the construction of school knowledge processes and no reflection on the theoretical matrices that inform them. An analogous referral is given to the management of learning environments - the teachers should be able to formulate and manage them. As for Evaluation, the teachers should be able to apply evaluation procedures and interpret students’ performance, especially those obtained in large-scale evaluations. The same happens when conducting pedagogical practices - the future teacher must be able to apply pedagogical practices consistent with the BNCC - the required skills do not lead to reflections. Professional practice is perceived as a technical domain.

Abilities related to professional engagement are associated with four other dimensions: commitment to professional development and student learning, participation in the school's pedagogical project, and dealing with families and the community. Professional development is materialized in the responsibility of the teacher himself with his training to meet the School demands. The commitment to learning, on the other hand, occurs through the recognition of principles established by the guidelines and not in their discussion and reflection. Participation in the pedagogical project implies collaboration - criticism, questioning, and observation - are not foreseen formulations. Finally, engagement with families and the community requires establishing dialogue channels to sharing responsibilities and seeking support.

Reflecting on abilities in the physical thinking formulation, Ricardo Karam and Maurício Pietrocola (2009) reflect on mathematical knowledge importance in the Physics teaching in which they distinguish technical and structuring qualification. According to the authors, Physics demands both. The techniques would be “related to the instrumental domain of algorithms, rules, formulas, graphs, equations etc.” (KARAM; PIETROCOLA, 2009, p. 190, our translation) and the structuring ones would turn to the mathematics use in external domains - that is, the understanding of mathematical knowledge in a way that one can “think mathematically the phenomena of the physical world, or, to read think mathematically the phenomena of the physical world, or, to read that same world through a mathematical language, or even, to structure the physical world through mathematics” (KARAM; PIETROCOLA, 2009, p. 194, our translation).

Karam and Pietrocola’s contribution seems productive. Considering what types of abilities the guidelines for teacher education convey. According to our analysis, they favor the development of technical capability aimed at the instrumental use of didactic-pedagogical knowledge and reference knowledge, following what is supposed to be necessary for the 21st-century economy. The abilities emphasize what the undergraduates must know how to do and not what they must know to fulfill the objectives foreseen for National Education. One of the pieces of evidence of this are the total absence of abilities that address ethnic-racial issues.

Difference recognition, as the new guidelines suggest, is not the same thing as understanding the create inequalities processes. This last operation demands reflection (and also criticism) on manifestations of inequality, especially those unfold from Racism. Without the necessary investment in the theoretical domain about how Racism manifests itself, it is impossible to plan didactic-pedagogical processes that promote Racism disapproval and its elimination. Professional commitment is essential. It is the State's duty and responsibility to ensure teachers access to continuing education, especially when it contributes to improving the Basic Education conditions of provision, affecting the training of all students.

The absence of reflections and effective referrals to ERER has damaging consequences. Since they are related to the discussions on Difference and Diversity, they participate, as we have already pointed out, in the processes of identity construction - individual and collective. They affect how each person perceives themsenves, their place in the world, their limits, and their possibilities. School culture also participates in the building national identity processes, especially from how the schools’ historical narrative is approached (COELHO, 2019). Thus, not including what the DCNERER foresees has implications for how identities can be approached at School, especially in the perception of the attributes of color, race, and ethnicity in the construction of inequalities.

Conclusion

In this paper, we analyze one of the aspects of the projected educational policy - the National Curriculum Guidelines for the Initial Teachers Training for Basic Education, formulated by the CNE (BRASIL, 2019b) - questioning how it forwards the ERER. Having the history teacher training pathway as the scope of our concern, we point out the place (or the absence of it) of the DCNERER in the guidelines proposed for the initial teacher training in history.

The analysis of the competencies and abilities to be appropriated by the future teachers suggests that the teacher training is confused with the undergraduate instrumentalization in the practices and actions domain that turn to the BNCC operationalization and the improvement of the performance of Basic Education students in large scale evaluation exams, as has already been pointed out by the specialized literature. However, when we consider the teacher training in history, it is clear that the principle adopted by the guidelines is, in general, the same present in the pathway of active degree courses.

In those History degree courses, teacher education is perceived as the historian instrumentalization for dealing with school history, assumed as the translation of historiographic knowledge for didactic purposes. However, the space destined for didactic-pedagogical expertise and the appropriation that they make of what the principles of ERER convey suggest that the new guidelines have great potential to affect the place occupied by historiographical knowledge. It is significant, in this sense, what the guidelines refer to in terms of professional practice, as mentioned in the previous pages: “pedagogical knowledge of the content, that is, the way these are worked in the classroom.” The subjects of a historiographical nature, aimed at dealing with the epistemology of history, the historiographic currents, the explanatory models on periods, themes, problems, etc. they tend to lose space for subjects that address how to teach this or that, as stipulated by the BNCC.

The new guidelines announce an even higher impact on the history teachers’ training, considering how the formative path forwards knowledge about the knowledge to be taught, how to teach, and the student. By disconnecting history knowledge from the teaching knowledge, considering the latter as the domain of technical abilities, they restrict the contributions that historical knowledge makes: different perspectives consideration, the investigation, the context analysis, and the formulation of questions. These attributes of historical knowledge have the potential to make the classroom space for knowledge production and the building of an attitude of questioning that is related to the formation of oneself, the exercise of citizenship, and the situation in the world, and, by extension, in the labor market.

The effectiveness of the proposed guidelines can make ERER's space even more restricted in history teacher training. As we have pointed out, space is already limited and does not promote alteration or criticism of the Eurocentric perspective. The absence of references to DCNERER, however, can suppress discussions, considering the little space that Africa, Afro-Brazilian Culture, and Indigenous Peoples occupy in the BNCC. That demands another study!

REFERENCES

ANUNCIACAO, Diana; TRAD, Leny Alves Bonfim; FERREIRA, Tiago. “Mão na cabeça!”: abordagem policial, racismo e violência estrutural entre jovens negros de três capitais do Nordeste. Saúde e Sociedade, São Paulo, v. 29, n. 1, e190271, 2020. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/sausoc/v29n1/1984-0470-sausoc-29-01-e190271.pdf . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem. São Paulo: HUCITEC, 1988. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. [Constituição (1988)]. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [2016]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm . Acesso em: 25 maio 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, p. 27833, 23 dez. 1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394.htm . Acesso em: 25 maio 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.639, de 9 de janeiro de 2003. Altera a Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para incluir no currículo oficial da Rede de Ensino a obrigatoriedade da temática "História e Cultura Afro-Brasileira", e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, p. 1, 10 jan. 2003. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2003/l10.639.htm . Acesso: 10 abr. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CP nº 03/2004, de 10 de março de 2004. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação das Relações Étnico-Raciais e para o Ensino de História e Cultura Afro-Brasileira e Africana. Brasília, DF: MEC, 10 mar. 2004a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/dmdocuments/cnecp_003.pdf . Acesso em: 19 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução CNE/CP nº 1/2004, de 17 de junho de 2004. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação das Relações Étnico-Raciais e para o Ensino de História e Cultura Afro-Brasileira e Africana. Brasília, DF: MEC , 17 jun. 2004b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/res012004.pdf . Acesso em: 20 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.645, de 10 de março de 2008. Altera a Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, modificada pela Lei nº 10.639, de 9 de janeiro de 2003, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para incluir no currículo oficial da rede de ensino a obrigatoriedade da temática "História e Cultura Afro-Brasileira e Indígena". Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, p. 1, 11 mar. 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/lei/2008/lei-11645-10-marco-2008-572787-publicacaooriginal-96087-pl.html . Acesso em: 10 abr. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CEB nº 14/2015, de 11 de novembro de 2015. Diretrizes Operacionais para a implementação da história e das culturas dos povos indígenas na Educação Básica, em decorrência da Lei nº 11.645/2008. Brasília, DF: MEC , 11 nov. 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=27591-pareceres-da-camara-de-educacao-basica-14-2015-pdf&category_slug=novembro-2015-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 21 maio 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular: Educação é a Base. Brasília, DF: MEC , 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_20dez_site.pdf . Acesso em: 14 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CP nº 22/2019, de 7 novembro 2019. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação). Brasília, DF: MEC , 7 nov. 2019a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=133091-pcp022-19-3&category_slug=dezembro-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 21 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019. Brasília, DF: MEC , 20 dez. 2019b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=135951-rcp002-19&category_slug=dezembro-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 14 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Cadastro Nacional de Cursos e Instituições de Educação Superior e-MEC. Brasília, 2020. Disponível em: https://emec.mec.gov.br/emec/nova. Acesso em: 16 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

CAIMI, Flávia Eloisa. Por que os alunos (não) aprendem História? Reflexões sobre ensino, aprendizagem e formação de professores de História. Tempo, Niterói, v. 11, n. 21, p. 17-32, 2006. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/tem/v11n21/v11n21a03.pdf . Acesso em: 05 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CAIMI, Flávia Eloisa. História escolar e memória coletiva: como se ensina? Como se aprende? In: MAGALHÃES, Marcelo; ROCHA, Helenice; GONTIJO, Rebeca(org.). A escrita da história escolar: memória e historiografia. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2009. p. 65-79. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTI, Erinaldo Vicente. A história encastelada e o ensino encurralado: reflexões sobre a formação docente dos professores de história. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 34, n. 72, p. 249-267, dez. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/v34n72/0104-4060-er-34-72-249.pdf . Acesso em: 05 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CERRI, Luis Fernando. A formação de professores de história no Brasil: antecedentes e panorama atual. História, histórias, Brasília, v. 1, n. 2, p. 167-186, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/hh/article/view/10730/9425 . Acesso em: 16 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CHALHOUB, Sidney; SILVA, Fernando Teixeira da. Sujeitos no imaginário acadêmico: escravos e trabalhadores na historiografia brasileira desde os anos 1980. Cadernos Arquivo Edgar Leuenroth, Campinas, v. 14, n. 26, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ifch.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/ael/article/download/2558/1968 . Acesso em: 05 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

COELHO, Mauro Cezar. Diferença e semelhança. In: FERREIRA, Marieta de Moraes; OLIVEIRA, Margarida Dias de(coord.). Dicionário de Ensino de História. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora, 2019. p. 85-90. [ Links ]

COELHO, Mauro Cezar; COELHO, Wilma de Nazaré Baía. As licenciaturas em história e a lei 10.639/03 - percursos de formação para o trato com a Diferença? Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 34, e192224, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/edur/v34/1982-6621-edur-34-e192224.pdf . Acesso em: 14 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

COELHO, Wilma de Nazaré Baía; COELHO, Mauro Cezar. Os conteúdos étnico-raciais na educação brasileira: práticas em curso. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 47, 67-84, mar. 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/n47/06.pdf . Acesso em: 08 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Marieta de Moraes; FRANCO, Renato. Desafios do ensino de história. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 41, p. 79-93, jan./jun. 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/eh/v21n41/05.pdf . Acesso em: 05 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Ricardo Frankllin; CAMARGO, Amilton Carlos. As relações cotidianas e a construção da identidade negra. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, Brasília, v. 31, n. 2, p. 374-389, 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/pcp/v31n2/v31n2a13.pdf . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

GOODSON, Ivor Frederick. Currículo: teoria e história. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995. [ Links ]

KARAM, Ricardo Avelar Sotomaior; PIETROCOLA, Maurício. Habilidades Técnicas Versus Habilidades Estruturantes: resolução de problemas e o papel da Matemática como estruturante do pensamento Físico. Alexandria, Florianópolis, v. 2, n. 2, p.181-205, jul. 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/alexandria/article/view/37960 . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

MACHADO JÚNIOR, Celso; BAZANINI, Roberto; MANTOVANI, Daielly Melina Nassif. The myth of racial democracy in the labour market: a critical analysis of the participation of afro-descendants in brazilian companies. Organizações & Sociedade, Salvador, v. 25, n. 87, p. 632-655, dez. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/osoc/v25n87/1984-9230-osoc-25-87-632.pdf . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

MONTEIRO, Ana Maria. Professores de História: entre saberes e práticas. Rio de Janeiro: Mauad X, 2007. p. 81-112. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Renilson Rosa; RIBEIRO JÚNIOR, Halferd Carlos; VALÉRIO, Mairon Escorsi. O “Legado” da Aprendizagem Histórica: refazendo percursos de leituras. Antíteses, v. 9, n. 18, p. 196-221, jul./dez. 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1933/193349764010.pdf . Acesso em: 14 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. Sistema Nacional de Educação articulado ao Plano Nacional de Educação. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 15, n. 44, p. 380-392, ago. 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v15n44/v15n44a13.pdf . Acesso em: 23 set. 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA, Tomáz Tadeu. Documentos de identidade: uma introdução às teorias do currículo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1999. [ Links ]

SILVÉRIO, Valter Roberto; TRINIDAD, Cristina Teodoro. Há algo novo a se dizer sobre as relações raciais no Brasil contemporâneo? Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 33, n. 120, p. 891-914, set. 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v33n120/13.pdf . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

REFERENCES

FACULDADE ESTADUAL DE CIÊNCIAS E LETRAS DE CAMPO MOURÃO. Atualização do Projeto de Implantação do Curso de Licenciatura Plena em História. Campo Mourão: FECILCAM, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://fecilcam.br/historia/data/uploads/ppp-curso-de-historia.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE GOIÁS. Projeto Pedagógico Curso de Licenciatura em História. Goiânia: IFG, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://cursos.ifg.edu.br/info/lic/lic-historia/CP-GOIANIA . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DO PARÁ. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Belém: IFPA, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://sigaa.ifpa.edu.br/sigaa/public/curso/ppp.jsf?lc=pt_BR&id=5321723 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DA INTEGRAÇÃO INTERNACIONAL DA LUSOFONIA AFRO-BRASILEIRA. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso Licenciatura em História - Bahia. São Francisco do Conde: UNILAB, 2017. Disponível em: http://www.unilab.edu.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PPC-HIST%C3%93RIA-Vol-VI.pdf. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DA INTEGRAÇÃO INTERNACIONAL DA LUSOFONIA AFRO-BRASILEIRA- CEARÁ. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso Licenciatura em História - Ceará. Acarape: UNILAB, 2018. Disponível em: http://www.unilab.edu.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/PPC.-V8.-Hist%C3%B3ria.-Semestral.03.-Abril.-2019-1.pdf. Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DE PERNAMBUCO. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Petrolina: UPE, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.upe.br/petrolina/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/PPC_UNIFICADO_HISTORIA_IMPLEMENTADO-EM-2020.1.-COM-EMENTAS.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA. Projeto do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Conceição do Coité: UNEB, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.uneb.br/conceicaodocoite/wp-content/uploads/sites/34/2017/02/PROJETO-PEDAG%C3%93GICO.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA. Projeto do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Eunápolis: UNEB, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.uneb.br/eunapolis/wp-content/uploads/sites/39/2017/02/PROJETO-PEDAG%C3%93GICO-3.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA. Projeto do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Itaberaba: UNEB, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.uneb.br/itaberaba/wp-content/uploads/sites/33/2017/02/PROJETO-PEDAG%C3%93GICO-3.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA. Projeto do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Salvador: UNEB, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.uneb.br/salvador/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/01/PROJETO-PEDAG%C3%93GICO-27.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DA BAHIA. Projeto do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Jacobina: UNEB, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.uneb.br/jacobina/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2017/01/PROJETO-PEDAG%C3%93GICO.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE MINAS GERAIS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Campanha: UEMG, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uemg.br/graduacao/cursos2/course/historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE MINAS GERAIS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Carangola: UEMG, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uemg.br/graduacao/cursos2/course/historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE MINAS GERAIS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Divinópolis: UEMG, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uemg.br/graduacao/cursos2/course/historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DE SANTA CRUZ. Projeto Pedagógico Curricular do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Ilhéus: UESC, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uesc.br/cursos/graduacao/licenciatura/historia/index.php?item=conteudo_ppc.php . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DO PARÁ. Projeto Pedagógico Curso de História. Belém: UEPA, 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://paginas.uepa.br/prograd/index.php?option=com_rokdownloads&view=file&Itemid=16&id=191:projeto-pedagogico-curso-de-historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE DO ESTADO DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Assú: UERN, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uern.br/controledepaginas/proeg-projetos-pedagogicos-assu/arquivos/4229ppc_historia_assa%C5%A1_uern.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DA PARAÍBA. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso História - Licenciatura. Campina Grande: UEPB, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://proreitorias.uepb.edu.br/prograd/cursos-de-graduacao/ . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE ALAGOAS - PALMEIRA DOS ÍNDIOS. Projeto Político e Pedagógico dos Cursos de Licenciatura Plena em História. Palmeira dos Índios: UNEAL, 2004. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uneal.edu.br/ensino/projetos-pedagogicos . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE GOIÁS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Formosa: UEG, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.formosa.ueg.br/conteudo/11364_ppc_de_historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE GOIÁS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Goiás, GO: UEG, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://cdn.ueg.edu.br/source/cora_coralina_117/conteudoN/6701/Projeto_Pedagogico_do_curso_de_Historia_UEG_Campus_Goias.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE GOIÁS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Morrinhos: UEG, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.historiamorrinhos.ueg.br/conteudo/16263_projeto_pedagogico . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE MARINGÁ. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso. Maringá: UEM, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.pen.uem.br/cursos-de-graduacao/campus-sede-maringa-pr-x/documentos/historia.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE RORAIMA. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso. Boa Vista: UERR, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.uerr.edu.br/historia/ . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DO OESTE DO PARANÁ. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História. Marechal Cândido Rondon: UNIOESTE, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://midas.unioeste.br/sgav/arqvirtual#/detalhes/?arqVrtCdg=9526 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO”. Projeto Pedagógico - Licenciatura em História. Assis, SP: UNESP, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.assis.unesp.br/#!/ensino/graduacao/cursos/historia/informacoes . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO”. Projeto Pedagógico de História. Franca: UNESP, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.franca.unesp.br/#!/ensino/graduacao/cursos/historia/ . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA FRONTEIRA SUL. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Graduação em História - Licenciatura. Chapecó: UFFS, 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.uffs.edu.br/campi/chapeco/cursos/graduacao/historia/documentos . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA FRONTEIRA SUL. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Graduação em História - Licenciatura. Erechim: UFFS, 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.uffs.edu.br/campi/erechim/cursos/graduacao/historia/documentos . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA INTEGRAÇÃO LATINO-AMERICANA. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História - Grau Licenciatura. Foz do Iguaçu: UNILA, 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.unila.edu.br/graduacao/historia-licenciatura/ppc . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE ALAGOAS. Curso de Licenciatura - História . Maceió: UFAL, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://ufal.br/estudante/graduacao/projetos-pedagogicos/campus-maceio . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE ALFENAS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História - Licenciatura. Alfenas: UNIFAL, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://academico.unifal-mg.edu.br/sitecurso/arquivositecurso.php?arquivoId=221 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE CAMPINA GRANDE. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Cajazeiras: UFCG, 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://cfp.ufcg.edu.br/portal/conteudo/UACS/PPC_HISTORIA.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS - GOIÂNIA. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Graduação em História, Grau Acadêmico Licenciatura . Goiânia: UFG, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.historia.ufg.br/up/108/o/Resolucao_CEPEC_2015_1364.pdf?1524515823 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História . Jataí: UFG, 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://historia.jatai.ufg.br/p/4534-projeto-pedagogico-do-curso-de-historia . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MATO GROSSO DO SUL. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso de Licenciatura em História. Três Lagoas: UFMS, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://historiacptl.ufms.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Completo_estrutura-20.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MATO GROSSO DO SUL. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso - Licenciatura em História. Campo Grande: UFMS, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://historiacptl.ufms.br/documentos/ . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MATO GROSSO. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Graduação em História (Licenciatura). Cuiabá: UFMT, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://sistemas.ufmt.br/ufmt.ppc/PlanoPedagogico/Download/131 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE RONDÔNIA. Projeto Político Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura Plena em História. Rolim de Moura: UNIR, 2008. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.historiarolimdemoura.unir.br/pagina/exibir/3140 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE RORAIMA. Projeto Político Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Boa Vista: UFRR, 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://ufrr.br/historia/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=2&Itemid=201 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de História - Licenciatura. Guarulhos: UNIFESP, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.unifesp.br/reitoria/prograd/pro-reitoria-degraduacao/cursos/informacoes-sobre-os-cursos . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO AMAPÁ. Projeto Pedagógico de Curso - Licenciatura Em História. Macapá: UNIFAP, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.unifap.br/historia/files/2018/04/PPC-Licenciatura-2017.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO AMAZONAS. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura Plena em História. Manaus: UFAM, 2006. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ufam.edu.br/attachments/article/256/PPC%20História%20Noturno%202006.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RECÔNCAVO DA BAHIA. Projeto Político Pedagógico do Curso de Licenciatura em História. Cruz das Almas: UFRB, [20--]. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ufrb.edu.br/historia/images/Arquivos/ProjetoPedagogicoHistLicencDiurno.doc . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso Superior de História - Licenciatura na modalidade presencial. Natal: UFRN, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://sigaa.ufrn.br/sigaa/public/curso/ppp.jsf?lc=pt_BR&id=111635057 . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO SUL E SUDESTE DO PARÁ. Projeto Pedagógico do Curso Licenciatura em História. Marabá: UNIFESSPA, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://crca.unifesspa.edu.br/images/ppc/4_-_-PPC-HISTORIA-2016-ATUALIZADO-2019_compressed.pdf . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019 [ Links ]

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO TRIÂNGULO MINEIRO. Projeto Pedagógico Curso de Graduação em História - Licenciatura. Uberaba: UFTM, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.uftm.edu.br/historia/projeto-pedagogico . Acesso em: 30 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

1The article presents partial data of the research in progress named History teacher training: an analysis of the degree courses in public universities (2002-2019), developed at the Universidade Federal do Pará. Translated by the authors.

2About national education system see (SAVIANI, 2010).

Received: October 04, 2020; Accepted: February 16, 2021

texto em

texto em