Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.39 Curitiba 2023 Epub 14-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.87513

Dossier - Education, Health and Childcare: knowledge, expertise and social practices

The Casulo day care centers in Amazonas, 1979-1990

*Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Manaus, SEMED; Universidade Federal do Amazonas, UFAM. Manaus, Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas - Brazil. E-mail address: kellymattos_am@hotmail.com

**Universidade de Brasília, UNB, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brazil. E-mail address: moyseskj180@gmail.com

***Universidade Federal do Amazonas, UFAM, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. E-mail address: persidamiki@ufam.edu.br

The text1 discusses the history of day care centers in Amazonas under the Projeto Casulo of Legião Brasileira de Assistência (LBA) between 1979, when the first daycare center opened, and 1990, the year in which the LBA reached 61 municipalities in the state. We assume that these day care centers emerged in a context of mass projects for children up to the age of six, implemented at a low cost, in collaboration with multilateral organizations, meeting Unicef requirements, such as the reduction of needs in material and cultural spheres, through the proliferation of these institutions throughout the country. We use the historical method with a social and cultural approach, having as procedures and instruments: documentary research, through journals, official and non-official documents, interviews, and oral reports. The findings reveal that the expansion of the day care centers occurred directly through operational units of direct execution, managed by the LBA, and indirectly through accredited operational units, in accordance with the National Security Doctrine - DSN.

Keywords: Early Childhood; History of Education; Social Rights; Public Policy

O texto discorre sobre a história das creches do Projeto Casulo da Legião Brasileira de Assistência (LBA), no Amazonas entre os anos de 1979, quando a primeira creche foi inaugurada, e 1990, ano em que a LBA atingiu os 61 municípios do Estado. Parte-se do pressuposto de essas creches surgirem em um contexto de execução de projetos em massa para as crianças com até 6 anos, implementados a baixo custo, em articulação com organismos multilaterais, atendendo às exigências do Unicef, como a redução das necessidades em esferas materiais e culturais, por meio da proliferação destas instituições em todo o país. O método histórico foi utilizado, com abordagem social e cultural, tendo como procedimentos e instrumentos: pesquisa documental, por meio de periódicos e documentos oficiais e não oficiais, entrevista e relato oral. Os resultados revelaram que a expansão do atendimento nas creches ocorreu por meio de unidades operacionais de execução direta, administradas pela LBA, e indireta, conveniadas, dentro dos ditames preconizados pela Doutrina de Segurança Nacional- DSN.

Palavras-chave: Primeira Infância; História da Educação; Direitos Sociais; Políticas Públicas

Introduction

This study approaches the daycare centers of Projeto Casulo (Cocoon Project), of the Legião Brasileira de Assistência (Brazilian Legion of Assistance), in Amazonas, between the years 1979 and 1990. It presents the preliminary findings of a doctoral research and aims to contribute to the history of early childhood education and, more specifically, to the understanding of the determining historical aspects, as well as to the development of public policies of education and assistance to poor children and working women, placing the context of their implementation and expansion in the periods of the Military Dictatorship and the New Republic.

The purpose is to situate education within social relations through historical research with a social and cultural focus, based on the authors Carlo Ginzburg (2002), Eric Hobsbawm, (1998), Moysés Kuhlmann Júnior & Paula Leonardi (2017), Edward Thompson (1981) and Raymond Williams (1992). For this objective to be accomplished, several documentary sources were consulted.

The survey in the virtual collections was conducted in editions of the newspapers Jornal do Comércio and Diário Oficial do Amazonas in the Hemeroteca Brasileira Digital (Brazilian Digital Library), the webpage of the Official Press of the State of Amazonas, and the Getúlio Vargas Foundation’s website.

In the physical collections, we collected documents in the editions of newspapers Jornal do Comércio and Jornal A Crítica at the Public Library of Amazonas and reports and other documents from the LBA collection, at the Social Security Documentation Center - CEDOCPREV, in Manaus.

Terezinha Gomes, a social worker who oversaw the Projeto Casulo in Amazonas in the 1980s, granted a photograph and also provided an oral report for the research.

Thus, the sources consisted of traditional documents, “textual documents recorded on conventional support, paper support,” and special documents “recorded on diverse supports, including sound, iconographic, digital, and micrographic sources, among others.” (RIBEIRO, 2016, p. 8).

The implementation of Projeto Casulo in Brazil

The first studies on Projeto Casulo, conducted close to its implementation in 1977, focused on its general objectives, situated between historical and political considerations. The historicity in these works, in most cases, did not correspond to the Project, which was virtually contemporaneous with the outputs, but to the trajectory of the Legião Brasileira de Assistência, which was founded in 1942. Among these works, the following stand out: Sonia Kramer (1984), 1. edition, 1981; Maria Aparecida Franco (1984; 1988); Lívia Maria Vieira (1986; 1988); Aldaíza Sposati & Maria do Carmo Falcão (1989); Maria Malta Campos; Fúlvia Rosemberg & Isabel Ferreira (2001), 1 edition, 1993; and Fúlvia Rosemberg (2001; 2002).

Other references include studies that reviewed the history of Brazilian early childhood education in general, as well as investigations on the history of early childhood education in Brazilian states and municipalities that found evidence of the LBA’s performance, such as in: Elisângela Mantagute (2009), in Curitiba-PR; Darci Terezinha Scavone (2011), in São Paulo-SP; Gabriela Darahem (2011), in Ribeirão Preto-SP; Patrícia Regina Brant (2013), in Florianópolis-SC; Caroline Conceição (2014), in Francisco Beltrão-PR; Larissa Montiel (2019) and Giseli Rodrigues (2019), in Naviraí-MS; and Aline Aderne (2020), in the state of Alagoas.

Projeto Casulo offered a simpler educational service for children, utilizing “[...] idle spaces and volunteer workers, from the perspective of community development.” The project, which launched in 1977, proposed expanding childcare centers with community participation, justifying compensatory treatment and criticizing “conventional” day care centers which, due to their high costs, would not be fitted to the reality of Brazil, a developing country (VIEIRA, 1988, p. 1, 5).

It was the “first mass national program,” with the objective of assisting a large number of children at a cheap cost, “to prevent their marginalization,” and “to offer mothers with free time to enter the labor market” in order to “increase family income” (KRAMER, 1984, p. 76).

Its origins may be traced back to the decade preceding its implementation, when the National Children’s Department (DNCr), which was associated to the Ministry of Health and was also in charge of the country’s childcare centers, devised a plan for the establishment of recreation centers. They were not executed at the time, but they served as a model for Projeto Casulo.

This Plan was prepared two years after the Latin American Conference on Children and Youth in National Development, in accordance with the recommendations of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund - UNICEF, and was based on the ideology of community development, indicating the installation of Recreation Centers in churches, but which appeared to have been produced with the objective of meeting the requirements for obtaining international loans (KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, 2000a).

The execution of Projeto Casulo took place after the establishment of a federal social assistance plan in accordance with the National Security Doctrine, with the following characteristics:

[...] objectives of assistance and integral child development, which expanded the exclusive perspective of compulsory school preparation but adopted a strong preventive connotation; a mass service perspective, expanding coverage at low cost, which would be achieved through simple constructions, the use of idle spaces or those provided by the community, and the participation of people in voluntary or semi-voluntary work (the community) (ROSEMBERG, 2002, p. 151).

The building of a Casulo daycare, which would care for children between four and eight hours a day, was done at the request of municipal halls, prelatures, social services, or the state. The LBA could finance “[...] food, teaching and consumable materials, equipment, construction material, and records, while the partner institution pays for personnel.” According to the author, there was also unpaid volunteer work (KRAMER, 1984, p. 76).

The Project was piloted in four states: Ceará, Rio Grande do Sul, Alagoas, and Rio Grande do Norte, and it became LBA’s main program in 1981. Between 1977 and 1987, there was a significant increase in the number of children assisted by the project across the country, with a growth rate of assistance increasing from 100 to 1,143%, or from 21,280 children in 1977 to 1,709.020 in 1987 (CAMPOS; ROSEMBERG FERREIRA, 2001; PINTO, 1984). According to an analysis of the IBGE yearbooks from 1977 and 1987, the children enrolled in Projeto Casulo in 1977 corresponded to 0.12% of the Brazilian child population, and in 1987 it was equivalent to 9.45% of all children assisted, demonstrating an increase in the percentage of assistance to the young population.

According to Luís Fernando da Silva Pinto (1984, p. 5.46), president of the national LBA between 1976 and 1979, federal contributions to Projeto Casulo and the Food Complementation Program were made in accordance with the “Community National Contract,” with equal per-capita allocations for all federation units. In 1984, Projeto Casulo was implemented in 13 federative units: Amazonas, Acre, Alagoas, Amapá, the Federal District, Espírito Santo, Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Paraná, and Santa Catarina (PINTO, 1984).

The Project was a humanitarian assistance policy part of “the strategies to combat psychological warfare” that was implemented in accordance with “the theory and practice of Community Development (CD).” (ROSEMBERG, 2001, p. 141-142). Through Projeto Casulo, the federal government penetrated directly into the municipalities, bypassing the state administration, by employing “marketing fitting to the Brazilian political moment: investing in children would imply investing in national security” (ROSEMBERG, 2001, p. 153).

An “unfortunate marriage between intergovernmental organizations and the military government in Brazil in the field of mass early childhood education in the 1970s,” with the cold war as a backdrop, and “the shared alliance [strategy] was the key concept of ‘community participation’” to implement these programs aimed at poor children, since it removed “the tensions, conflicts, contradictions, and particularities that mark each national history.” (ROSEMBERG, 2001, p. 141, emphasis added). Fúlvia Rosemberg concluded that this mass preschool model, even if it resulted from “a claim by women (as had happened in Brazil), could generate and reinforce new discriminations against women, the poor, and black children as a result,” and recalled that this sequel was also identified in the UNICEF program implemented in partnership with the community in English-speaking Africa in the 1950s (ROSEMBERG, 2001, p. 54).

According to Moysés Kuhlmann Júnior, the Superior Military College saw the establishment of vacancies for children under the age of six in Casulo day care centers as a solution to social problems such as marginality, poverty, mortality, and promiscuity. This approach was taken to oppose the alien ideals of communism, but it paradoxically embraced the alien ideas of international organizations. This policy, however, had no effect on the many social movements that erupted in Brazil during the military dictatorship, because:

[...] Aspirations for an equal society would be far more indigenous than the beliefs that maintained this country’s imperialist voracity, where social programs have a history of excelling in minimum concessions, at the limit of its ability to suppress conflicts through repression (KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, 2000a, p. 10-11).

In Brazil, the actions of social assistance agencies in the field of education created “[...] a fog that obscured the historical replication of social disparities and the set of social rights of the working class, including the right to day care and pre-school.” (KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, 2000b, p. 491). According to Fúlvia Rosemberg, these were not necessarily low-cost policies because they entailed indirect costs that were not covered by the federal government. This meant that the government made limited investments, leaving the majority to day care facilities, lowering the quality of these programs that:

[...] were incomplete, implemented as emergency solutions, however extensive, which usually results in low-quality service and great instability, being aimed specifically at poor populations who, from the perspective of affirmative policies, require and are entitled to complete and stable programs as measures to correct historical and systematic injustices (ROSEMBERG, 2002, p. 57).

In Brazil, projects of this nature were governmental initiatives based on international interests that concentrated actions directed at disadvantaged children through the federative body. Thus, the government deviated from its promise to the implantation and implementation of more uniform and structured public policies for the country.

Projeto Casulo in Amazonas

On January 12, 1979, Jornal do Comércio reported that at 10 am that day Creche Casulo (Casulo day care center) would be inaugurated, “[...] in the presence of senior national leaders of the Brazilian Legion of Assistance Foundation,” which would be administered by the Director Coordination of LBA Social Service, at Avenida Joaquim Nabuco, 1193. It would provide recreation and meals to up to 120 children between the ages of three and six every day for four hours (CRECHE CASULO, 1979, p. 4; INAUGURA..., 1979).

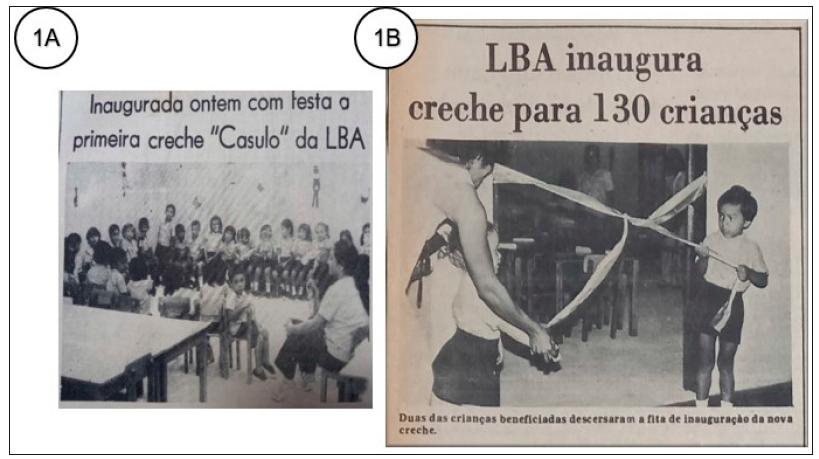

The event was covered in newspapers Jornal do Comércio (1979) and Jornal A Crítica (LBA..., 1979) the next day. Under the headline “LBA’s first ‘Casulo’ day care center opened yesterday with a party,” a black and white photograph of the inside of a room with 25 children appears, one standing and the rest sitting in chairs arranged in a circle appears in Jornal do Comércio. They wear a uniform that consists of light-colored shirts with elbow-length sleeves, black knee-length shorts, dark shoes, and most of the girls appear to be holding dolls. On the right side of the image, there is a woman sitting on a small children’s chair, her legs crossed and her arms on her knees, with her attention focused on the children. She is most likely the entertainer in charge.

The woman is dressed in a light shirt with elbow-length sleeves, long black pants, and light high-heeled sandals. Her long dark hair is pulled back into a ponytail. On the left side of the image is a light table, on the right is a corner of a light table, and on the wall are several figures such as butterflies, a giraffe, and two figures that mimic the human form (Figure 1 A, p. 7).

The story began by considering that the day care center’s inauguration would be an auspicious start to the International Year of the Child, with this “wonderful project that aspires to aid poor and destitute children in our capital.” Guilherme Garcia Gomes, then local director of the LBA, presided over the “competitive act,” which was attended by Otilia Marinho, head of the institution’s Social Service, Ivete dos Santos Alves, coordinator of the Day Care Program, Arnaud Ferreira de Araújo, coordinator of the LBA in Rio de Janeiro, and D. João de Souza Lima, Metropolitan Archbishop of Manaus. It was also reported that the aforementioned project foresaw the establishment of another 50 days care centers in the capital that year, the second of which was expected to open in March, at the Social Center of the Cachoeirinha neighborhood, for 120 children aged 0 to 6, 30 of whom would attend semi-boarding school (INAUGURADA..., 1979, p. 3).

The story in the newspaper A Crítica (1979) was titled “LBA inaugurates daycare center for 130 children,” which was ten more than the number stated in Jornal do Comércio (LBA...,1979). A black and white image of two children, a boy on the left and a girl on the right, in uniform, unveiling the opening ribbon in front of the entrance to a room appears beneath the headline. A woman’s profile can be seen next to the girl, assisting her in holding the end of the ribbon. There are chairs and tables in the back of the room, as well as two adults in a corner (FIGURE 1 B, p. 8). The caption reads, “Two beneficiary children unraveled [sic] the ribbon for the inauguration of the new day care center.” The text informs that the LBA received a budget of one million four hundred thousand cruzeiros for the construction of a day care center that would serve children aged three to six in a day school and would provide medical, pedagogical, recreational, and, in the future, dental assistance. Free of charge, the objective was “to provide adequate nutrition, guided recreation and sociability for children” and not literacy. The numbers for the Cachoeirinha neighborhood day care center differed from the article in Jornal do Comércio, which reported a capacity of 80 children. The article also states that the LBA reached an agreement with another ten daycare centers in the neighborhoods of Compensa, Aleixo, Crespo, Japiinlândia, and the municipality of Iranduba. As for day care centers under construction, it mentions the municipalities of Silves, Parintins, Iranduba, Tabatinga and border areas (LBA..., 1979, p. 5).

SOURCE: Newspaper Jornal do Comércio (INAUGURADA..., 1979, section 1, p. 3); Newspaper A Crítica (LBA..., 1979, p. 5). Collection: Public Library of Amazonas. (Elaborated by the authors).

FIGURE 1 NEWS ON THE INAUGURATION OF CASULO DAY CARE CENTERS IN MANAUS -AM

The existence of Urban Social Centers was publicized the following year in the neighborhoods Raiz, Japiim - south of Manaus, and Flores, in Manaus’ central-south zone; and the information that the Secretariat of Labor and Social Service - SETRASS, assisted 144 children aged 3 to 6 years old, in the morning, where they received “two meals, a snack, and lunch.” There were also “mothers’ clubs, youth groups, elders’ groups, a Work Commission, Catechesis Group, Theater Group, Scout Group, and lectures” in the Social Centers. It was also reported that a Social Center would be established in the municipality of Itacoatiara, along with a Casulo day care center (CENTRO...,1980, p. 2; AMAZONAS, 1980a, p. 2).

In 1980, LBA hosted the 1st Meeting of Instructors of the day care centers of Projeto Casulo in the auditorium of the Center for Human Behavior Studies - CENESC, in collaboration with the Archdiocese of Manaus, CENESC, Amazonas municipalities, and the Military Command from Amazonas. The event was supervised by social worker Maria de Nazaré Soares and served to “address current inadequacies in the system for carrying out work allocated among vulnerable communities,” according to a statement from the LBA’s regional president, Belmiro Jorge. These “distortions,” which were not mentioned in the press, would be improved within a program created by the LBA, the approval of which would be “disclosed to the Meeting participants.” In total, 40 instructors participated in the event, with 18 of them coming from Amazonas’ countryside (LBA PROMOVE..., 1980, p. 3).

By means of SETRASS Ordinances 026/80 and 077/80, the social worker Maria Júlia Alves de Almeida was assigned as manager of Projeto Casulo, and coordinator Maria das Graças Lima Rodrigues was in charge of the operationalization of day care centers in the Project (AMAZONAS, 1980b; 1980c).

There are service orders from SETRASS in editions of Diário Oficial do Amazonas between the years 1980 and 1982, which granted authorizations for visits by Maria Júlia Alves de Almeida and Dayse Albuquerque Amorim to the municipalities of Eirunepé and Maués in Amazonas’ countryside. They were responsible for providing the essential supplies to the Social Center under the SETRASS/FLBA agreement for the Project, as well as managing the operations at the Social Center and the use of the Casulo day care center project’s budget. The average length of stay for a visit was 7 to 8 days (AMAZONAS, 1980c; 1981a; 1982a).

The newspapers Jornal do Comércio and Diário Oficial do Amazonas published articles about the day care centers, such as one about Amine Lindoso, president of the Volunteer Center of Amazonas (CVA), who announced in a speech the expansion of Projeto Casulo in Manaus, receiving a check for Cr$ 450 thousand from the company Phillips of Amazonas as a donation:

[...] The LBA initiated a nationwide initiative to expand Casulo daycare centers to accommodate children who spend most of the day away from their working parents. According to Dona Amine, Projeto Casulo will expand in January of next year to help about 120 families spread among the capital’s neighborhoods [...] (CVA RECEBEU..., 1981, p. 2).

The news mentioned the need to sensitize other companies in the Industrial District so that they “follow Phillips’ example in visiting the CVA” and become aware “of the work carried out in favor of needy communities” (CVA RECEBEU..., 1981, p. 2).

In the 1982 Annual Report (AMAZONAS, 1982b), of the Division of Social Service of the State Superintendence of Amazonas, data were presented on 35 daycare centers of Projeto Casulo in Manaus, two of which were directly implemented, and 33 were indirectly implemented. Of these, 17 were associated to the Catholic Church, one to the Social Center, one to the Manaus Workers’ Circle, four to state and municipal secretariats, two to the Amazonas Volunteer Center, four to foundations, and four to institutes. The identification of each one of them along with their location, are displayed on the map prepared by us, which is available at Vasconcelos (2022a).

According to the “Statute of Social Works of the Community of Nossa Senhora da Graças - (Antônio Aleixo)” of May 6, 1981, which was created for organizing “a civil society with all the rights and obligations inherent to legal persons governed by private law,” the majority of these agreements were with the Catholic Church, similar to the one that exists currently in Colonia Antônio Aleixo. In the document, made up of 14 articles, there is a reference to Casulo day care centers in article 3, which established as the “main purpose of the Society” the services of “educational institutions such as Kindergarten, Casulo daycare centers, Catechesis, in addition to classes for adults”, and Community clubs such as Youth and Ladies (Mothers). According to the Statute’s Article 5:

Art. 5 - The Membership of the Society is composed of members of the Mission of the Franciscan Priests of the Third Order Regular in Amazonas who work in the region, and by priests and lay people who, committing themselves to providing services free of charge, be admitted by its board of directors (AMAZONAS, 1981b, p. 14, emphasis added).

Among the 1984 agreements, we also draw attention to “Casulo do Vovô” (Grandpa’s Cocoon), a day care facility that operated in conjunction with that of Dr. Thomas, a nursing home run by the city, because: “The project at Dr. Thomas Foundation was called Casulo Vovô because it was an integration of generations: the elderly and children. People interacted with the kids by talking, singing, and telling stories.” (GOMES, 2021, research collection):

[...] We had, as a principle, a pilot plan in Manaus, which were the day care centers that belonged to the LBA and which operated in the social center of Cachoeirinha, and one over there in Joaquim Nabuco, where our LBA headquarters was located. At 73 years old, memory isn’t very good, but there were several girls who were supervisors in the education projects area. It was a project that covered the entirety of Amazonas, not just the city of Manaus, but also the countryside, where several municipalities maintained day care centers through the Project.

Projeto Casulo, which we implemented at Dr. Thomas Foundation and engaged in integrated work with the elderly, was a very significant highlight at the time. It was a very wonderful experience [...] it was a very beautiful project, we could even observed how the elderly interacted with the kids at the day care center because it was in the same location as the Foundation, where the elderly were located. On the same property as the elderly, but not in the same building, there was a daycare center. It was a very good experience and, if I’m not mistaken, it was our experience in Amazonas, in LBA of Amazonas (GOMES, 2021, research collection).

According to information from the 1982 (AMAZONAS, 1982b), Annual Report, 34 “operational units” associated with Projeto Casulo existed in the countryside of the State that year, with a majority of agreements with the Catholic Church (17), followed by City Halls (8) and the Amazonas Military Command (8), and one agreement with SEDUC. The names and locations of these units are shown on the map that is accessible at Vasconcelos (2022b), elaborated by the authors.

It is important to note that in the description of the “physical situation of the unit” there are two categorization options: “isolated” or “next to”, which presents five classification alternatives: “church”, “school”, “health center”, “social center” and “others”, respectively. That is, the term “day care center” did not appear among the possibilities for identifying these units (AMAZONAS, 1982).

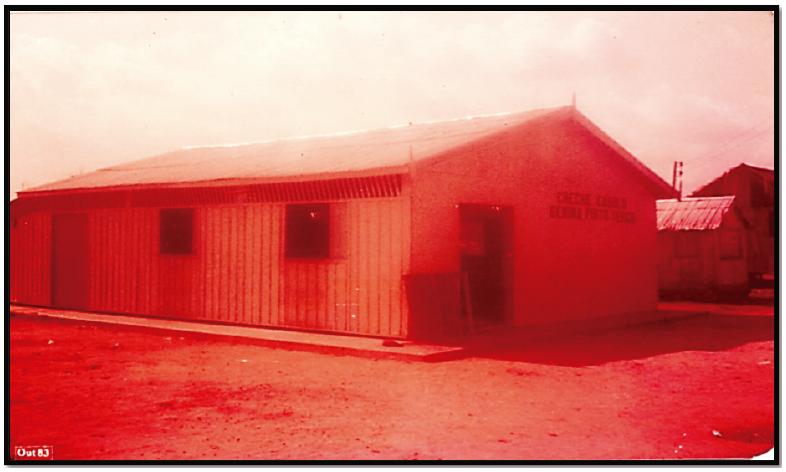

Yet, in a photograph of a facility with the following identification on its exterior, “Genina Pinto Terco Casulo day care center” dated October 1983, we noticed that the term “day care center” was used to describe units such as the one in São Sebastião do Uatum (FIGURE 2, p. 11). The picture depicts a scissor-shaped roof on a light-colored building from a diagonal angle. A door that is open on the left side of the front wall, which appears to have been built of brick, is surrounded by a barrier made of wooden slats that was likely designed to keep kids inside the building. The identification for the daycare center is written in capital letters at the top of the wall to the right. The side wall features two windows that look to be open and closed, and was noticeably constructed of wood. On the left side of the picture, there are portions of what appear to be two shacks, a wide plot of grass, and a short sidewalk that surrounds the building.

In the newspaper Diário Oficial, we find the disclosure of values destined for Projeto Casulo, similar to those that took place between 1982 and 1984 under the administration of Paulo Nery, allocating funds to SETRASS so that they could be used, among other things, in the “service of Pre-School (Casulo daycare centers)”, without specifying the precise amount for this service or for which units it would be destined. One of them mentions that 300 children would receive assistance for four hours (AMAZONAS, 1982c, p. 3; 1982a; 1984).

SOURCE: Personal collection of Terezinha Gomes 10/1983 (Research collection).

FIGURE 2 VIEW OF THE FACADE AND SIDE OF THE GENINA PINTO TERCO CASULO DAY CARE CENTER.

In 1987, the LBA operated in 17 municipalities in the state: Amaturá, Atalaia do Norte, Barcelos, Benjamin Constant, Boca do Acre, Canutama, Ipixuna, Japurá, Jutaí, Lábrea, Pauini, Santa Izabel do Rio Negro, Santo Antônio do Içá, São Gabriel da Cachoeira, São Paulo de Olivença, Tabatinga and Tonantins (MINISTÉRIO DA PROVIDÊNCIA E ASSISTÊNCIA SOCIAL, 1988, p. 9).

The Ministry of Social Security and Social Assistance, through the bodies associated to it, National Institute of Social Security - INPS, National Institute of Medical Assistance of Social Security - INAMPS, Institute of Administration of Social Security and Social Assistance - IAPAS, LBA, and National Foundation of Minors’ Well-Being (FUNABEM), made a commitment to the National Security Council to “provide more effective treatment of issues related to the municipalities that make up the border strip,” and began to coordinate SINPAS’s activities (MINISTÉRIO DA PROVIDÊNCIA E ASSISTÊNCIA SOCIAL, 1988, p. 2).

With this, the LBA joined the Federal Government Action Plan/ Border Strip Program - PAG/PFF, intensifying its projects and/or programs included in the Action Plan and Goals of the Ministry of Social Security and Social Assistance/ National System of Social Security - MPAS/SINPAS in the border municipalities of Amazonas, Amapá, Roraima and Pará, to “ensure permanent and integrated action with State Governments, City Halls, Military Organizations and Entities/Institutions of a social nature”. In the aforementioned Plan, the LBA was responsible for:

the provision of social assistance, establishing that the “activities will be implemented from the diagnosis to be reflected in the intervention plan, developed through the design of a framework of needs and community effort,” having as main objectives:

- Strengthening of the municipal structure.

- Support for community initiatives.

- Stimulation of community organization.

- Support and/or strengthening of institutions

- Creation of initiatives such as daycare programs and projects, professional recycling and training, social microenterprises, civil registration and legal aid, assistance for the elderly and the severely disabled, sports and community recreation, etc.; identifying the most appropriate viable initiatives in each municipality or locality (MINISTÉRIO DA PROVIDÊNCIA E ASSISTÊNCIA SOCIAL, 1988, p. 5).

Through the Regional Managements, the LBA only began to reach the 61 municipalities in the Amazon region after 1990, when “[...] all LBA actions were taken to the countryside (day care, assistance for the elderly and disabled, [...])” through agreements. “Offices were established in conjunction with the Municipality in each strategically important city on the great rivers, from which actions radiated to other Municipalities”:

The Managements were headquartered in Manaus (Rio Negro/Solimões region, comprising 16 municipalities); in Itacoatiara (region of the middle Amazon river, with seven municipalities); in Parintins (lower Amazon region, with six municipalities); in Benjamin Constant (upper Solimões river region, with six municipalities); in Tefé (Solimões/Japurá region, with eight municipalities); in Lábrea (a region on the Purus river, with five municipalities); in Eírunepé (region of the Juruá river, with six municipalities); in Manicoré (Madeira river region, with five municipalities); and in São Gabriel da Cachoeira (upper Rio Negro region, with three municipalities) (LEGIÃO BRASILEIRA DE ASSISTÊNCIA, 1994a; 1994b, p. 4).

Final considerations

By examining the web of connections between the sources analyzed (MAGALHÃES, Justino, 2004), we found that Projeto Casulo was implemented in Manaus in accordance with the ideas popular during the dictatorship period in Brazil and which spread across the New Republic. They were articulated with SETRASS and a number of institutions, primarily religious ones, with a predominance of the Catholic Church. Day care centers operated in several spaces, such as Social Centers, Churches, schools, and kindergartens through agreements, where additional activities were provided, also incluing the families of the “cocoon” children, a term used by Luís Fernando Pinto (2002).

We observed that these agreements became more prevalent in the 1980s at the same time that movements to fight for day care centers in Manaus were organized by the Commission of Metallurgical Women Workers of the Metallurgist Workers Union and originating from the University Working Women’s Committee, created on March 8, 1980, at the Federal University of Amazonas (TORRES, 2005; ASSIS, , 2013; BATISTA, 2018; SILVA, V., 2012, 2021; SILVA, D., 2021).

Beginning from the understanding that “cultural analysis cannot be limited to the level of formal and conscious beliefs” (WILLIAMS, 1992, p. 26), we observe that, in this context, economic and governmental policy constructed strategies for educational policy, among them Projeto Casulo, with reference to the care of young children in day care centers.

We observed that, on the one hand, social movements pushed for the establishment of day care centers as being necessary for working women (working class, poor); however, on the other hand, government care was provided in an incipient manner and with an educational welfare vision within a dissemination policy, which gave LBA power as a model of flawless service.

By articulating hypotheses and evidence (THOMPSON, 1981; GINZBURG, 2002) based on the dialectical process of validating and confirming the knowledge generated, we believe that, through social movements and civil society claims, day care services gained visibility in the periodical press and became the agenda of public policies.

We conclude that, in many situations, Casulo day care centers would be more of a part-time pre-school program for kids between the ages of four and six than a full-time day care facility for kids between the ages of zero and six. Despite being a project aimed at serving a large number of children with little investment, we cannot disregard its relevance in ensuring access to early childhood education and meeting the basic needs for survival of poor children since, in these places, children received education, food, and medical care.

REFERENCES

ADERNE, Aline da Silva Ferreira. A educação da infância em Alagoas em fábricas e usinas antes da Constituição Federal de 1988. 2020. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Alagoas, Maceió, 2020. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS, Superintendência Estadual. Divisão de Serviço Social. Relatório Anual. 1982b. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Quarta-feira, 07 de abril de 1982a, ano LXXXVIII, número 24.986. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Quarta-feira, 16 de junho de 1982c, ano LXXXVIII, número 25032. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Quinta-feira, 02 de outubro de 1984, ano XC, número 25598. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Quinta-feira, 14 de maio de 1981b, ano LXXXVII, número 24765. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Quinta-feira, 22 de outubro de 1981a, ano LXXXVII, número 24.877. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Segunda-feira, 06 de outubro de 1980c, ano LXXXVI, número 24.615. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Sexta-feira, 20 de agosto de 1982a, ano LXXXIX, número 25079. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Sexta-feira, 22 de fevereiro de 1980a, ano LXXXVI, número 24.461. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

AMAZONAS. Diário Oficial. Terça-feira, 24 de junho de 1980b, ano LXXXVI, número 24.543. Estado Federal do Amazonas. [ Links ]

ASSIS, Maria Tereza Oliveira de. A política pública de creche em Manaus e a luta do movimento de mulheres por sua efetivação. Dissertação (Mestrado em Serviço Social) - Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, 2013. [ Links ]

BATISTA, Elane da Silva. Políticas Públicas de creche da SEMED em Manaus: organização do atendimento e da oferta no Sistema de Ensino Público do município. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Amazonas, Manaus, 2018. [ Links ]

BRANT, Patrícia Regina Silveira de Sá. Do perfil desejado - A invenção da professora de educação infantil da Rede Municipal de Ensino de Florianópolis (1976-1980). Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, 2013. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Maria Malta; ROSEMBERG, Fúlvia.; FERREIRA, Isabel M. Creches e Pré-Escolas no Brasil. 1. ed. São Paulo: Cortez; Fundação Carlos Chagas, 2001. [ Links ]

CENTRO SOCIAL DE ITACOATIARA INAUGURADO EM MARÇO PRÓXIMO. Jornal do Comércio, Manaus, 22/02/1980, p. 2. [ Links ]

CONCEIÇÃO, Caroline Machado Cortelini. Práticas e representações da institucionalização da infância: bebês e crianças bem pequenas na creche em Francisco Beltrão/PR (1980/1990). Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, 2014. [ Links ]

CRECHE CASULO. Jornal do Comércio, Manaus, 12/01/1979, caderno 1, p. 4. [ Links ]

CVA RECEBEU Cr$ 450 MIL DA PHILLIPS. Jornal do Comércio, Manaus, 12/11/1981, p. 2. [ Links ]

DARAHEM, Gabriela Campos. Contribuição para a história da educação infantil em Ribeirão Preto: experiências de funcionários e professoras das escolas municipais de educação infantil (EMEIs). Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia) - Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2011. [ Links ]

FRANCO, Maria Aparecida Ciavatta. Da assistência educativa à educação assistencializada: um estudo de caracterização e custos de atendimento a crianças pobres de zero a seis anos de idade. Brasília: INEP, 1988. [ Links ]

FRANCO, Maria Aparecida Ciavatta. Lidando pobremente com a pobreza: análise de uma tendência no atendimento a crianças “carentes” de 0 a 6 anos de idade. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 51, p. 13-32, 1984. Disponível em: http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br//index.php/cp/article/view/1457. Acesso em: 23 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. Relações de força: história, retórica, prova. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. [ Links ]

GOMES, Terezinha de Jesus Monteiro. [Creches Casulo]. WhatsApp: [transcrição de áudio]. 28 jul. 2021. 13:06. 1 mensagem de WhatsApp. [ Links ]

GOMES, Terezinha de Jesus Monteiro. Vista da fachada e lateral da Creche Casulo Genina Pinto Terco. 1983. 1 fotografia. 15 x 10. [ Links ]

HOBSBAWM, Eric. Sobre história. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

IBGE. Anuário Estatístico do Brasil, 1977. Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodicos/20/aeb_1977.pdf. Acesso em: 08 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

IBGE. Anuário Estatístico do Brasil, 1987-1988. Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/biblioteca-catalogo?id=720&view=detalhes. Acesso em: 08 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

INAUGURADA ONTEM COM FESTA A PRIMEIRA CRECHE “CASULO” DA LBA. Jornal do Comércio, Manaus, 13/01/1979, p. 3. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Sonia. A Política do Pré-escolar no Brasil: a Arte do Disfarce. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Achimé, 1984. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, Moysés. Histórias da educação infantil brasileira. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 14, p. 05-18, 2000a. Trimestral. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbedu/a/CNXbjFdfdk9DNwWT5JCHVsJ/abstract/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 25 set. 2020. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, Moysés. Educando a infância brasileira. In: LOPES, Eliana Marta Teixeira; FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes Faria; VEIGA, Cynthia Greive (Orgs.). 500 anos de educação no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2000b. p. 469-496. [ Links ]

KUHLMANN JÚNIOR, Moysés; LEONARDI, Paula. História da educação no quadro das relações sociais. História da Educação, v. 21, n. 51, p. 207-227, 2017. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/asphe/article/view/66163. Acesso em: 25 set. 2020. [ Links ]

LBA INAUGURA CRECHE PARA 130 CRIANÇAS. A Crítica, Manaus, 13/01/1979, p. 5. [ Links ]

LBA PROMOVE ENCONTRO DE MONITORES DO PROJETO CASULO. Jornal do Comércio, Manaus, 23/04/1980, caderno 1, p. 3. [ Links ]

LEGIÃO BRASILEIRA DE ASSISTÊNCIA. A LBA no Amazonas. ASCOM: 1994a. 10p. [ Links ]

LEGIÃO BRASILEIRA DE ASSISTÊNCIA. Superintendência Estadual do Amazonas. Relatório. ASCOM: 1994b. 13p. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, Justino Pereira de. Tecendo Nexos: História das Instituições Educativas. Bragança Paulista: Editora Universitária São Francisco-EDUSF, 2004. [ Links ]

MANTAGUTE, Elisângela Iargas Iuzviak. Estudo sobre as primeiras creches públicas da Rede Municipal de Educação de Curitiba (1977-1986). 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2009. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA PROVIDÊNCIA E ASSISTÊNCIA SOCIAL. Fundação Legião Brasileira de Assistência. Plano de Ação do Governo Federal - PAG. Programa da Faixa de Fronteira - PFF. Relatório da Ação da LBA -1987. Março. 1988. [ Links ]

MONTIEL, Larissa Wayhs Trein. Da Assistência à Educação Infantil: a transição do atendimento à Infância no Município de Naviraí - MS (1995-2005). Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, 2019. [ Links ]

PINTO, Luís Fernando da Silva. Luiz Fernando Pinto II (depoimento, 2001). Rio de Janeiro, CPDOC/Ministério da Previdência e Assistência Social - Secretaria de Estado de Assistência Social, 2002. Disponível em: http://www.fgv.br/cpdoc/historal/arq/Entrevista568.pdf. Acesso: em: 12 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

PINTO, Luís Fernando da Silva. O social inadiável. São Paulo: Fundação Salim Farah Maluf, 1984. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Dreyson. Conservação em acervos fonográficos: preservar para não restaurar. TCC (Graduação em Arquivologia) - Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, 2016. [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Giseli Tavares de Souza. História do clube de mães e as origens do atendimento à criança pequena em Naviraí/MS (1974-1990). Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados, Dourados, 2019. [ Links ]

ROSEMBERG, Fúlvia. A LBA, o Projeto Casulo e a doutrina de segurança nacional. In: FREITAS, Marcos C. de. História social da infância no Brasil. São Paulo: USF/Cortez, 2001, p. 141-161. [ Links ]

ROSEMBERG, Fúlvia. Organizações multilaterais, estado e políticas de educação infantil: history repeats. Cadernos de Pesquisa, n. 115, p. 25-63, 2002. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/cp/a/PJ9b3xz5MFWFgh6TFLz7Tzh/abstract/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 13 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

SCAVONE, Darci Terezinha de Luca. Marcas da história da creche na cidade de São Paulo: as lutas no cotidiano (1976-1984). Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade São Francisco, Itatiba, 2011. [ Links ]

SILVA, David Xavier da. Políticas Públicas de Educação Infantil: Creches municipais da cidade de Manaus. 2021. Tese (Doutorado Interestadual em Educação) - Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Manaus, 2021. [ Links ]

SILVA, Vanderlete Pereira da. Organização e gestão da Educação Infantil em Manaus - uma análise de seus marcos regulatórios. 2012. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - CED - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2012. [ Links ]

SILVA, Vanderlete Pereira da. Mães manauaras e a educação das crianças pequenininhas: pluralidades históricas e resistências na cidade da floresta. 2021. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Capinas, Campinas, 2021. [ Links ]

SPOSATI, Aldaíza; FALCÃO, Maria do Carmo. LBA: identidade e efetividade das ações no enfrentamento da pobreza brasileira. São Paulo: EDUC, 1989. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, Edward Palmer. A miséria da teoria. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar Editores, 1981. [ Links ]

TORRES, Iraildes Caldas. As Novas Amazônidas. Manaus: Editora da Universidade Federal do Amazonas - EDUA, 2005. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, K. R. de M. Unidades Operacionais do Projeto Casulo em Manaus (1982), 2022. Google Maps. Google. Disponível em: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1sxKWJRawfPLmzXRU1ztZgC3cwlYtc9Zm&ll=-3.123682927176562%2C-60.00267602565753&z=15. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, K. R. de M. Unidades Operacionais do Projeto Casulo no interior- AM (1982), 2022. Google Maps. Google. Disponível em:https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=11fXmeymkikSPiWodo2omZIibROBedKwm&ll=-3.435690392205771%2C-64.16865895&z=6. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Lívia Maria Fraga. Creches no Brasil: de mal necessário a lugar de compensar carências. Rumo à construção de um projeto educativo. 1986. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte, 1986. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Lívia Maria Fraga. Mal necessário: creches no Departamento Nacional da Criança (1940-1970). Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 67, p. 3-16, 1988. Disponível em: https://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/cp/article/view/1215. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

WILLIAMS, Raymond. Com vistas a uma sociologia da cultura. In: WILLIAMS, Raymond. Cultura. Tradução de Lólio Lourenço de Oliveira. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1992. p. 9-31. [ Links ]

Received: September 07, 2022; Accepted: March 21, 2023

texto em

texto em