Introduction

At the end of the World Education Forum in 2015, UNESCO representatives recognized how complex education has become in the contemporary world and stated that “[...] there is a growing need to reconcile the contributions and demands of the three regulators of social behavior: society, state, and market” (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2015, p. 11). As the main tasks of contemporary education, this forum has listed: having sustainable development as a central concern; reaffirming a humanistic approach to education; local and global policymaking in a complex world; and recontextualizing education and knowledge as global common goods. Such tasks gain support among researchers and social organizations that understand the social function of the school according to its contribution to the integral formation of the human being, interactions with the different realities, and the institutional and personal commitment to transforming society, based on the educational processes developed from the school space-time.

These callsigns are not a novelty. Throughout the 20th century, discussions about school and schooling reaffirmed the necessary relationship between education, the local environment, and the social context, also counting subjects’ integral development. However, the 21st century has evidenced the gap between the speed of widespread social change and the delays of educational institutions’ answers. “This new context of societal transformation demands that we revisit the purpose of education and the organization of learning” (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2015, p. 16) considering that new human, pedagogical, social, cultural, environmental, and political needs signal the emergence of a new educational paradigm.

According to Rivas (2019), two classic paradigms define the purposes of an educational system: the adaptive and the transformative. In the first one, schooling is designed to meet the needs of the society, market, religion, nation, or current culture, since “the educational systems were good at replicating stabilities: religious beliefs systems; national identities; translation of scientific knowledge into the children’s world; industrial model work routines” (Rivas, 2019, p. 25, our translation)3; even if these sources continue to shape education today, they do not respond to “[...] new urgencies, demands and external questions that no longer ask for certainties or long doses of temporal continuity” (Rivas, 2019, p. 25, our translation)4. In the transformative paradigm, it is the school that challenges reality, as proposed by Freire’s pedagogy of questioning (2014). In it, Freire points to the imperative of changing the educational institution itself: from an education focused on the memorization and transmission of knowledge toward interactive processes of learning and problem-solving; from the obligation to attend school toward the search for meaning in the educational processes; from the normalization of the contents toward the personalization of knowledge, so that learning branches out to the subjects.

Rivas (2019, p. 26, our translation)5 warns that it is not a matter of choosing between adaptation or transformation, but of “reading the society in which our students live and where they will act in a wide range of situations that demand different modes of action”. That is because the transformative paradigm maintains two continuities in relation to the adaptive paradigm: the scientific basis of the knowledge produced and transmitted from the school space-time; and the socialization of subjects from the institutional circuit, as opposed to the social normalization of discrimination, intolerance, injustice, competitiveness, and accumulation of material goods as a greater value, and in a way that “[...] fosters a meeting culture, peaceful coexistence, solidarity, and different forms of collaboration that irrigate values of social inclusion” (Rivas, 2019, p. 36, our translation)6.

In Brazil, the transformative paradigm dates to the first decades of the twentieth century. Among its many advocates, one must highlight Anísio Teixeira, a reference of the New School movement and a passionate defender of high-quality public education, and Freire and his liberation pedagogy focused on reading the world, the emancipation of the human being, and society’s transformation. According to these educators, this transformation begins in the classroom but directs itself to the structure of the educational system. Both defend the universalization of basic education and the use of pedagogical methods more appropriate to the reality of students to promote a dialogical relationship between the content produced in the classroom and the subjects’ own lives. Thus, the school is an institution with a strategic role in the process of socialization and sociability of students, in the integral formation of citizens, and in the construction of a more just and egalitarian society.

Besides transforming the world into a global village, the advent of information and communication technologies and social networks in the late twentieth century has shaped other dynamics of interpersonal, social, cultural, political, and economic relationships that demand different ways of contributing to individuals’ education. Integral formation, interaction between teachers and students, new ways and methodologies of teaching and learning, preparation for work and social inclusion, recognition of multiple knowledges, relationship between schooling and society dynamics, among other aspects, signal the expected changes for the 21st century school. Thus, the debate on education points to pragmatic needs related to teaching and learning practices; the new subjectivities that emerge amid political, social, and cultural plurality; and the consequent need to build a new place for the school in the contemporary world scenario, in line with the emerging educational paradigm. Considering all these aspects “[...] in short, it is necessary to defend and to rethink the school. We must learn to make visible the values that are built in the cultural space of education and take on the profound challenge of redefining its goals with good sense and a reflective spirit” (Rivas, 2019, p. 36, our translation)7.

In this debate, “innovation” often seems like a magic word that solves all the questions addressed to the contemporary school. Educational innovation has become an umbrella under which different conceptions of education, educational projects, and pedagogical practices are housed, not always innovative in the sense advocated by education researchers, but with undeniable appeal to families, students, and social groups in general. Although the immediate association between educational innovation and the use of communication technologies is common, innovating in education implies more than incorporating new tools into the teaching and learning processes developed in the classroom.

Regarding this issue, Serdyukov (2017) analyses the general conceptions of the term and confirm the distinction made by Theodore Levitt: “Creativity is thinking up new things. Innovation is doing new things” (apudSerdyukov, 2017, p. 8). For the author, whatever innovations are adopted in educational institutions, they always concern the improvement of educational processes. Van Velzen et al. (1985, p. 48) define school improvement as “[...] a systematic and sustained effort aimed at changing learning conditions and others intrinsically related to the event itself – in one or more schools – with the aspiration of achieving school goals more effectively”. The same idea is reinforced by Romero (2017, p. 145, our translation) 8:

The concept of improvement is interesting because it rescues the idea that changes do not operate by demolition, but are made from what exists, by reconstruction. Because there are no other teachers than those that there are, and no other students. So the phrase ‘this is what there is’, which is usually used in a conformist tone, should indicate the starting point. There is no other starting point, you must start from what there is.

These statements suggest an inversion of perspective in the debate about the contemporary school: instead of waiting until a new educational paradigm is consolidated, which involves social, political, and cultural factors beyond the school context, and then implement new school configurations, the focus is on improving the daily school dynamics and the processes of teaching and learning, engendering a paradigmatic change. In brief, reflections on contemporary education should result in changes to the educational practice, raising questions about the means and paths through which educational innovation goes. If tradition and continuity cannot respond to the new demands of contemporary education, where is the starting point to innovate in the school?

Innovation requires three major steps: an idea, its implementation, and the outcome that results from the execution of the idea and produces a change. In education, innovation can appear as a new pedagogic theory, methodological approach, teaching technique, instructional tool, learning process or institutional structure that, when implemented, produces a significant change in teaching and learning, which leads to better student learning. So, innovations in education are intended to raise productivity and efficiency of learning and/or improve learning quality

(Serdyukov, 2017, p. 8).

According to the author, improving the quality of learning can include “[...] attitudes, dispositions, behaviors, motivation, self-assessment, self-efficacy, autonomy, as well as communication, collaboration, engagement, and learning productivity”, reason why educational innovation “[...] concerns all stakeholders: the learner, parents, teacher, educational administrators, researchers, and policy makers and requires their active involvement and support” (Serdyukov, 2017, p. 8). In this sense, it is not simply a question of renewing teaching and learning methods but of changing the references that have guided the schooling processes; in other words, to adopt twenty-first-century technologies maintaining the twentieth-century learning practices will not improve the effectiveness of teaching. Aguerrondo (2017) emphasizes the intrinsic relationship between educational innovation and improving the school results, which certainly involves educators, principals, and school dynamics, but she makes an option for a student-centered perspective:

Innovation is any change that allows moving from academic knowledge to a research and development approach; from a passive learner to a learner who can actively learn; from the transmission of only conceptual knowledge to the transmission of knowledge as complex content

(Aguerrondo, 2017, p. 101, our translation)9.

The author recognizes the student as a strategic actor in discussions about education in the 21st century. Although research and productions on contemporary school and education abound, few consider students’ perceptions about the educational system, educational projects, school dynamics, school goals, contributions to the formation of the individuals, other possibilities of educating, etc. Thus, students are not heard, and the adult perspective ends up being the single reference in the discussions on educational innovation. This does not necessarily mean that researchers and educators are out of step with students’ perceptions, but simply that improving school processes should involve actively listening to all education subjects, and that students, especially High School ones, finishing basic schooling, can bring good contributions to the debate.

In this perspective, the reflections developed in this article are based on a survey conducted in Catholic schools; although the sample makes a cut of this modality of education and the analysis considers the peculiarities of the confessional school space-time, it also presents contributions to education in general since contemporary educational needs include Catholic education. It is likely that students living other schooling experiences will identify with many perceptions presented here and that they point out divergent experiences due to subjective differences, school trajectory, and social context. Given the complexity of the contemporary world and the dynamics that marks the interactions between the local and the global, there is a universal appeal to transform the school and the schooling processes, and students demonstrate this need, endorsing aspects of the educational project, criticizing the content approach, pointing out gaps in school processes, and drawing other perspectives for the school.

Methodological Procedures

The doctoral research that bases these appointments is linked to the National University of Rosario, Argentina. It problematizes the place of Catholic schools in the contemporary educational scenario. Eight principals, six High School coordinators, 28 pastoralists, and 157 students from six Catholic schools in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, belonging to different men and women’s religious congregations, were involved in the research by free choice. The study has a qualitative and descriptive methodology and, given the diversity of subjects and places from which they perceive the educational activity, different instruments for data collection were used. This procedure is indicated by Vasilachis de Gialdino (1992) and Arias Valencia (2000), among others, to apprehend the complexity of the researched theme. Furthermore, “[...] in the relationship between two or more methods, the possibility of balancing results, weighing results, enriching the understanding of the results arises and, once insurmountable inconsistencies occur, new horizons of problems, new questions are opened” (Samaja, 1992, p. 29, our translation)10.

Principals and High School coordinators presented their perceptions through interviews, defined by Sautu et al. (2005, p. 48, our translation) 11 as “[...] a systematized conversations that aim to obtain, retrieve, and record life experiences stored in people’s memory”. We opted for semi-structured interviews for the possibility of reconstructing the contents of the subjective theory using three types of questions: opened questions, answered based on the knowledge that the subjects have at hand; controlled ones, related to theories and directed to the researcher’s hypotheses and theoretical assumptions; and confrontational ones, which correspond to the theories and relationships presented until then by the interviewee (Flick, 2009). All questions addressed the subjects’ perceptions about the school’s daily life, also relating them to the contemporary context.

As pastoralists group tends to organize by projects and/or educational segment, but work as a team, we decided to involve them in group discussions, for, as listed by Flick: they enable the perception of “[...] everyday forms of communication and relationships”; “[...] correspond to the way in which opinions are produced, expressed, and exchanged in everyday life”; and eventual differences between the group “[...] are made available as a means of validating statements and points of view” (Flick, 2009, p. 182, our translation)12.

The students freely chose to participate in the research, after being invited by their coordinators, respecting the criterion of being in the second or third grade of High School. Their perceptions were recorded using two instruments, a written ten-question questionnaire and a free drawing. Cea D’Ancona (1996, p. 240, our translation) 13 describes the written questionnaire as “[...] the application of a standardized procedure to collect information – oral or written – from a sample of people about structural aspects; either certain socio-demographic characteristics or opinions about a specific topic”. The questions addressed the students’ school experience, from their trajectory in the Catholic school, and the prospects for their future after schooling. The advantage of the written questionnaire is the possibility of:

[...] positioning the subject, quickly and simply, in front of inductors that facilitate the transit to other different inductors and even within the same instrument, which will facilitate the possibility of producing, in these spaces, distinct meanings that facilitate the amplitude and the complexity of its various expressions

(González Rey, 2005, p. 51, our translation)14.

After answering the questionnaire, students were motivated to represent the place of the school in their lives by drawing with paper, crayons, colored markers, pens, and pencils. This option was due to the recognition of the image’s influence on the contemporary world, with a special appeal to adolescents, since:

Art is the social technique of emotion, a tool of society which brings the most intimate and personal aspects of our being into the circle of social life. It would be more correct to say that emotion becomes personal when every one of us experiences a work of art; it becomes personal without ceasing to be social

Natividade, Coutinho and Zanella (2008, p. 12, our translation) 15 refer to Vygotsky to state that “[...] creator activity includes both the cognitive and volitional aspects as well as the emotional, as it is the meaning of reality that is objectified through drawing and, through its intermediate, transformed”. The drawings added relevant information to the research because “[...] considering drawing as a creator activity, one can think that it expresses the author’s feelings and the way the reality is appropriated by him” (Natividade; Coutinho; Zanella, 2008, p. 12, our translation)16.

The responses were analyzed according to Qualitative Epistemology and its concept of subjective meanings, defined as “[...] symbolic-emotional units, in which the symbolic becomes emotional from its own genesis, just as emotions become symbolic, in a process that defines a quality of this integration, which is precisely the ontological definition of subjectivity” (González Rey; Martínez, 2017, p. 63, our translation)17. For the authors, the subjective meanings are “the most elementary, dynamic, and versatile unit of subjectivity”, highlighting that “its emergence is not a sum, but a new type of human process [...] that emerges in culturally organized social life, allowing the integration of the past and the future as an inseparable quality of the current subjective production” (González Rey; Martínez, 2017, p. 63, our translation)18. As said, this research has involved the various subjects of scholar education and their perceptions were presented according to the place from which they perceive the school dynamics and are involved in the educational process. This article focuses on the students’ reports and inquiries.

Results and Discussion

All the data provided by the students concerns their perceptions of their trajectory in the Catholic school, addressing issues such as the educational project, curriculum, participation in non-compulsory activities, experiences in other spaces, and interactions with educators. From these perceptions, expressed by the written word and images, the students problematize the relationship between the school and the needs of the contemporary world, identifying as central issues the limitations related to the plastered educational system; contributions of the educative project to the formation of subjects; the elaboration of life project by High School teenagers; and the meanings of the schooling according to the students’ perceptions.

The plastered educational system

A sensitive issue in the discussions of contemporary education refers to the “plastered” educational system, as defined by a student, and its greatest symbol, the Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (ENEM, National High School Exam). Implemented in 1998 to establish common parameters for basic education, ENEM is now considered an indicator of the educational quality of the school, according to its position in the ranking of university admissions, especially the public ones. For this reason, the organization of High School tends to disregard the perspective of integral education and consequently the development of socio-emotional competences, formation for citizenship, contact with other realities, and elaboration of the life project, as defined in the Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais (PCN, National Curriculum Parameters) and the Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC, Common Curriculum National Base). Therefore, schools focus on transmitting the contents required for the exam, which results in an extensive scholar workload and fragmented curriculum, in which the areas of knowledge are settled in isolation and the dialogues among them are frequently disregarded.

In Catholic schools, High School students have almost full-time classes, with the specific times spent in school activities varying from one school to the other. Some schools apply tests every Saturday as a way of preparing students for the university entrance exam. Several students recognize that they spend more time at the school than at home. Some consider it a positive thing, due to their affective relationship with the school space-time and the people with whom they spend time there; others recognize it as a necessity related to the extensive workload, as something that could be different. Even though students’ complaints about the school curriculum are common, many extend their criticisms to the educational system itself, highlighting its different aspects, such as the standardization of teaching:

As the curriculum is the same for Brazil as a whole, you feel a little clueless about what you like best, since you have to learn everything (S1S5)19.

We have many compulsory disciplines, and few means to guarantee maximum knowledge in relation to a specific area or at least find out which one we really fit and like. We also don’t experience many practices of certain contents (S1S19).

The school still “fits” the students in a lot and I’m sure that it is possible to make teaching more flexible with the existing structure and respecting the rules of MEC [Brazilian Ministry of Education] (S1S1).

Because of the school contents’ standardization, many students think that the High School’s primary focus on preparing them for ENEM is negative:

They are more concerned with us getting a high score in ENEM than with our professional option (S2S11).

Teaching more about professions, our rights as people, and economics is something that the school should do. Focus less on ENEM and more on what will happen after it (S1S4).

Besides these content-related criticisms, several students are assertive in pointing out the changes they would like to see in the educational system:

I would like students to have more voice and freedom, I would like us to be prepared for life and not for ENEM, I wish they would encourage freedom and creativity, I would also like if all students were included in [school] projects (S1S19).

A greater discussion of social issues, aiming at an openness and dialogue for future generations (S2S33).

The same thing I wish for all schools, the change in our current educational system, new teaching and assessment methods, less standardization, and more flexibility (S1S6).

[I would like more] flexibility in schedules and more freedom within the environment (S6S10).

A student notes: “We are stuck with a system that does not work for everyone, as some people need special attention in some areas and others in others [areas]” (S1S20). Finally, another student summarizes the impact of this educational model on formation: “I believe that the focus on the ENEM ranking will result in a generation of lost students who are unprepared for life” (S1S3).

Educational project and formation of the subjects

Students’ criticism to the plastered educational system is based on their perceptions about the educational project of the Catholic school in which they study. Although none used the expression “educational project”, many refer explicitly to the humanist foundation of Catholic education, both recognizing it in their school routine and pointing out its absence in teaching and learning processes. Among the students who assess the humanistic approach in a positive way, several highlight the importance of Catholic education for their personal formation and ability to interact with others:

I believe that the school practically raised me and taught me a sense of empathy and sympathy towards the human being (S3S8).

Besides being a school that allows students to be individual, living together with difference makes me a better person, with a more open mind (S5S12).

I’ve learned to respect the different and to help others. I also learned not to be afraid to be who I am (S1S13).

In this regard, they also highlight the importance of the relationship between teachers and students, perceived in different ways. The students avoid generalization and report different forms of living together with their various teachers: some are recognized for their affective and close relationship with students – another foundation of the Catholic school’s educational project – and others are mentioned strictly for their teaching function:

There are adults who understand our needs and the future we look forward to, help us ‘dream’ and motivate us. Other adults do nothing more than what is compulsory as a teacher (a teacher is different from an educator) and still believe that the work of school educators20 is unnecessary, because it does not help in ENEM and entrance exams (S1S1).

I believe that some inter-relational aspects could be improved, either the coordination-student or coordination-teacher. On some occasions, there could be more dialogue (S6S22).

Teachers do not always pass only the subject to be studied, many talk about everyday matters (S5S32).

They [teachers] are very flexible and some of them talk to us on an equal footing (S4S5).

I think the school should open more conversation with students (S5S13).

Other students highlight the school’s contribution to shape a critical worldview that is empathetic and welcoming of differences, in line with the diversity in the contemporary world and the necessary dialogue with other subjectivities and cultures.

With everything that is discussed at school, it opened my way of thinking, which makes seeing/looking at things in a different way that will lead me to try to change the thinking of the world (S6S6).

With the knowledge acquired at the school, I can become a more political and more present citizen (S2S3).

[I have learned to] respect others more, be more empathetic, and give space for others to speak and know how to listen to them (S5S17).

Several students relate these learnings, generally identified as socio-emotional skills, with participating in extra-class projects. They perceive the volunteering and pastoral experiences as differential elements of Catholic education:

The school is concerned with social and family issues, carrying out various activities aimed at discussing these issues, such as series projects and volunteering (S1S13).

Pastoral care gives a lot of support in how to be a good person and helped a lot in social baggage, being an influencer or actor of social changes (S2S29).

Through volunteering I have a greater sense of the world abroad, outside my social bubble (S4S5).

The development of pastoral and social projects in partnership with other institutions expands the school action beyond its own walls and favors students’ contact with other institutional circuits, socio-cultural realities, and subjectivities. These students expand their notion of territory and, thus, have access to learning that the strict formatted space of the classroom does not allow. In these reports, they indicate in their own words the expected role of the educational institution for their subjective constitution process, identifying contributions and gaps in the socializing role of school education. In this sense, although Catholic school affirms its option for an integral conception of education, not all students see their school experience as the source of an integral formation; some recognize the school for its strict function as a transmitter of knowledge, without necessary implications on the formation of subjects for life in society.

An important finding from the data was the relationship between the positive perception of Catholic schooling and participating in extra-class projects, which provide varied learning and bring other meanings to the schooling process. Thus, students who restrict their school life to attendance in compulsory classes demonstrate more difficulty in understanding the meaning of the school education and its institutional role on subjectivation processes, in the present time and for the future. Therefore, they signal that school processes must necessarily extrapolate the classroom, classes, and the focus on the transmission of knowledge: the core of schooling is the integral formation of the subjects and their interactions with the contemporary world, helping them discover pathways and possibilities inside the context of continuous changes.

High School, teenagers, and life project

Although the interactions with other subjects and realities beyond the school space-time are considered fundamental to the development of students, not many of them adhere to these projects. A student justifies it saying that “I did not participate in any [extra-class activity], due to the lack of time” (S2S10). Others express the same idea, referring to the school workload as the main reason for it. Klein and Arantes (2016, p. 150, our translation) 21 explain the importance of these projects as they provide learnings that go beyond the school space-time: “Students understand that participation in projects and student representation are important for their life projects as they enable understanding and action towards society”. This issue is considered a transversal axis of High School, according to the BNCC. This makes sense as at the end of basic education, adolescents are obligated to face an unavoidable change from the position of students, characterized by belonging to a known, affective, and familiar institutional environmental, toward an uncertain future, whose design implies the task of making choices today. Therefore, High School also marks a rupture in adolescents’ trajectories: “Life itineraries continue to maintain a certain stability, at least for the duration of the educational journey. For this reason, the end of secondary school awakens a set of experiences associated with the choice of a future what-to-do, which means living disrupting experiences with the inevitable process of subjective rearrangement” (Rascovan, 2016, p. 248, our translation)22.

Students express different perceptions on how the school contributes to this transition, according to their schooling experiences. The majority points out a gap between the school space-time and other social environments, and between their conditions as students and adolescents. In this sense, they live the tension pointed out by Dubet and Martucelli (1998, p. 196, our translation) 23, because the school promotes: “[...] a rupture between the student and the adolescent. In adolescence, a non-school ‘self’ is formed, a subjectivity and a collective life independent of the school, which ‘affect’ school life itself. A whole sphere of the experience of individuals is developed in the school, but without it”.

Some students confirm this dissociation, reporting that many experiences expected during their current stage of vital development are not welcomed at school. One comments that the educators “seem to never have been young” (S1S4), and others complement:

It is difficult to be understood as a teenager and to be taken seriously. Sometimes, I abstain for fear of not being taken seriously, since on top of that, they [the adults] are also authorities (S3S8).

Due to the age difference, they often end up not understanding the position of young people (S2S6).

Most adults show impatience and do not understand the issues of adolescents’ lives (S3S6).

While they have been working with young people for a long time, they revive the world of adults (S5S7).

[The educators] were once teenagers like us, but being a teenager today is different (S6S30).

Some educators, most of them, understand me and are flexible and welcoming in our relationships. However, others are very inflexible and do not put themselves in students’ shoes (C1E17).

These students confirm what Beard (2018, p. 19) noticed: “For people who deal exclusively in preparing others for the future, we educators are surprisingly reluctant to embrace the new. Our own experience biases us against it”. Others indicate how they wish the school to deal with these teenager issues:

The school must be a safer and more welcoming place for young people (S4S10).

I don’t see that it is a place that shows how to listen, respect the opinion of others, not to impose. The school is a test of patience for me (S6S15).

I would like the school to have more projects that provide care for the individual itself, reflective classes (C3E5).

As seen, some students understand this dissociation as an intergenerational issue or as the school’s failure to provide a favorable environment for the adolescents’ development. Others, however, relate it to the standardization of teaching, the education focused on content transmission and the emphasis on preparing for ENEM, which also brings consequences in defining future pathways:

The school ‘teaches’ us everything from all areas, but unfortunately it never allowed flexibility for us to focus on the areas that we are most interested in, making it impossible to approach the area of [personal] desire, let alone employment (S1S18).

The school helps me understand what I DON’T want to do with my life, due to boring school subjects and classes, like Geography and Portuguese. It is not always the teachers’ fault (S5S6).

Do treat students according to our age and let us be conscious and responsible for our actions, as there is a lot of childishness in our treatment that will not leverage our adult life (S2S6).

In the opposite perspective, some students recognize schooling as a positive and fundamental experience for their whole education, but they point out different aspects of this contribution:

School is a time for learning, where we discover more about ourselves and the world. Debates, classes, fights, crying, everything will be missed (S3S2).

I think the school helps a little, yes. Given the diversity of subjects and classes we have, we can see the areas that most attract us and that we would like to use further in our lives (S1S12).

The school helped me a lot in increasing my autonomy and preparing myself for life. I became much more responsible and open-minded to the world (S5S25).

The school’s formation of the human being creates professionals more interested in social changes and concerned with the others around us (S1S7).

Regarding the definition of a professional career, a relevant concern at the end of High School, several students miss a more assertive orientation. While the range of professional options, especially in the areas of technology, non-school education, and arts and culture, has expanded and created other fields of professional activity that extrapolate the traditional professions, opening a vast field of possibilities, generally schools do not keep up with these changes. Many students report how limited the views of most educators on academic career and options for future professional work can be, confirming the distance between the school education and the contemporary world.

The school is closed to limited worldview options. Limited view: Medicine and Law, blah blah blah (S2S30).

The school made me who I am in the essence, but not with the profession (S6S14).

The school has the role of guiding us on the path to entering a good university but did not influence me at all in the choice of the graduation/profession (S2S24).

The school does not help you decide what you are going to do in the future. There is a lack of lectures, classes, and demonstrations of the [professional] options. In general, students are not aware of the huge possibilities and breadth of their options (S1S4).

Students that present a positive vision about how the school has contributed to their personal life project options are also involved in pastoral projects, volunteering, and non-compulsory educational activities related to culture, art, sports, and interaction with other social spaces; they usually interpret their schooling experience in a more positive way than students who do not participate on these initiatives and identify learnings from these experiences provided by school:

[I like] the way the student is treated in activities focused on ENEM but also in relation to other subjects, such as sports, leisure, psychological (S3S9).

Thanks to some initiatives I already mentioned, activities that are outside the classroom, I feel that the school helps me a lot (S1S1, underlined by the student).

From experiences like the [solidarity] mission, I felt motivated to return to my place of origin and make a difference there, like fighting against slavery-like work and other forms of work without their basic rights guaranteed (S2S19).

The projects that I identify with are related to activities that I will carry out as an adult (S1S3).

High School students and the meanings of schooling

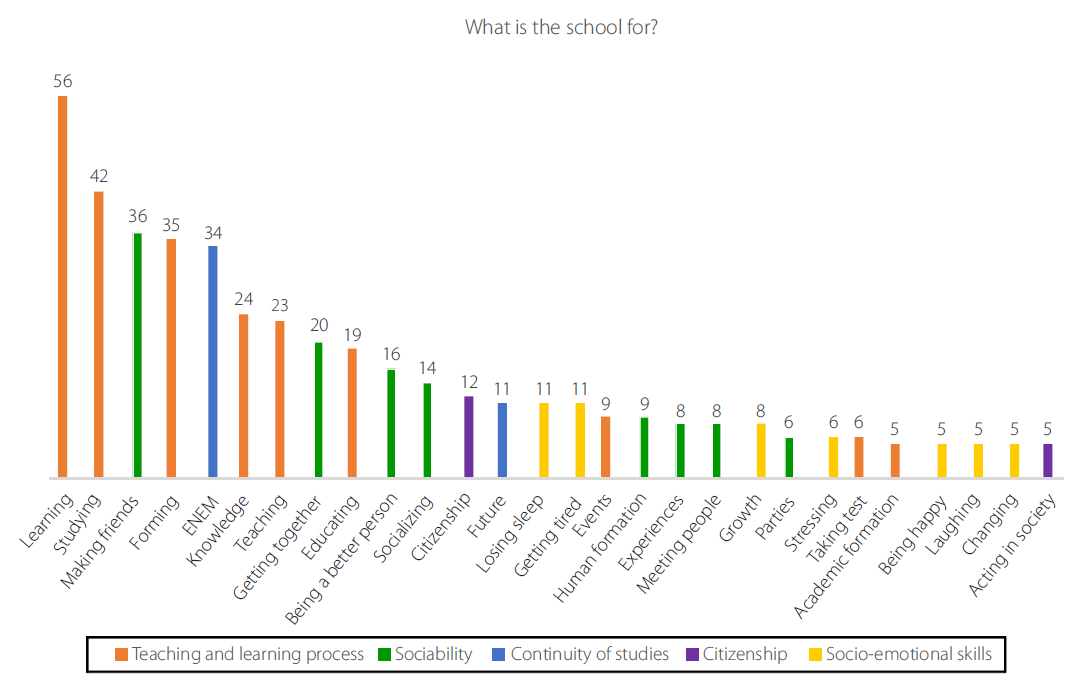

At the end of the questionnaire, students were asked to summarize: What is the school for? The Graph 1 shows off the most mentioned words, and how many times were mentioned.

Source: Elaborated by the author. Belo Horizonte/MG (2020).

Graph 1 Words most mentioned by students to express the purpose of the school.

The responses were grouped into the categories Teaching and learning process, Sociability, Continuity of studies, Citizenship, and Socio-emotional skills. The most mentioned words are related to (1) the student’s job – “learning” (56) and “studying” (42) – and (2) the functions of the school – “forming” (35), “knowledge” (24), “teaching” (23) and “educating” (19) – appear later, complemented by “future” (11), “events” (9), “taking tests” (6) and “academic formation” (5). ENEM (34) is among the most mentioned words, but not the top mentions, signaling that despite their concerns with entering the university, students recognize other important elements in the schooling experience.

Sociability-related aspects are expressed in more words, which is not surprising: because they are teenagers, they attach great importance to “making friends” (36), “getting together” (20), “being a better person” (16), “socializing” (14), “human formation” (9), “experiences”, “meeting people” (8), “parties” (6). Citizen education appears in two words – “citizenship” (12) and “acting in society” (5) – and socio-emotional aspects, in seven: “losing sleep”, “getting tired” (11), “growth” (8), and “stressing” (6), “being happy”, “laughing”, “changing” (5). Many perceptions are repeated, while several students bring freer and non-standard associations on this and other issues.

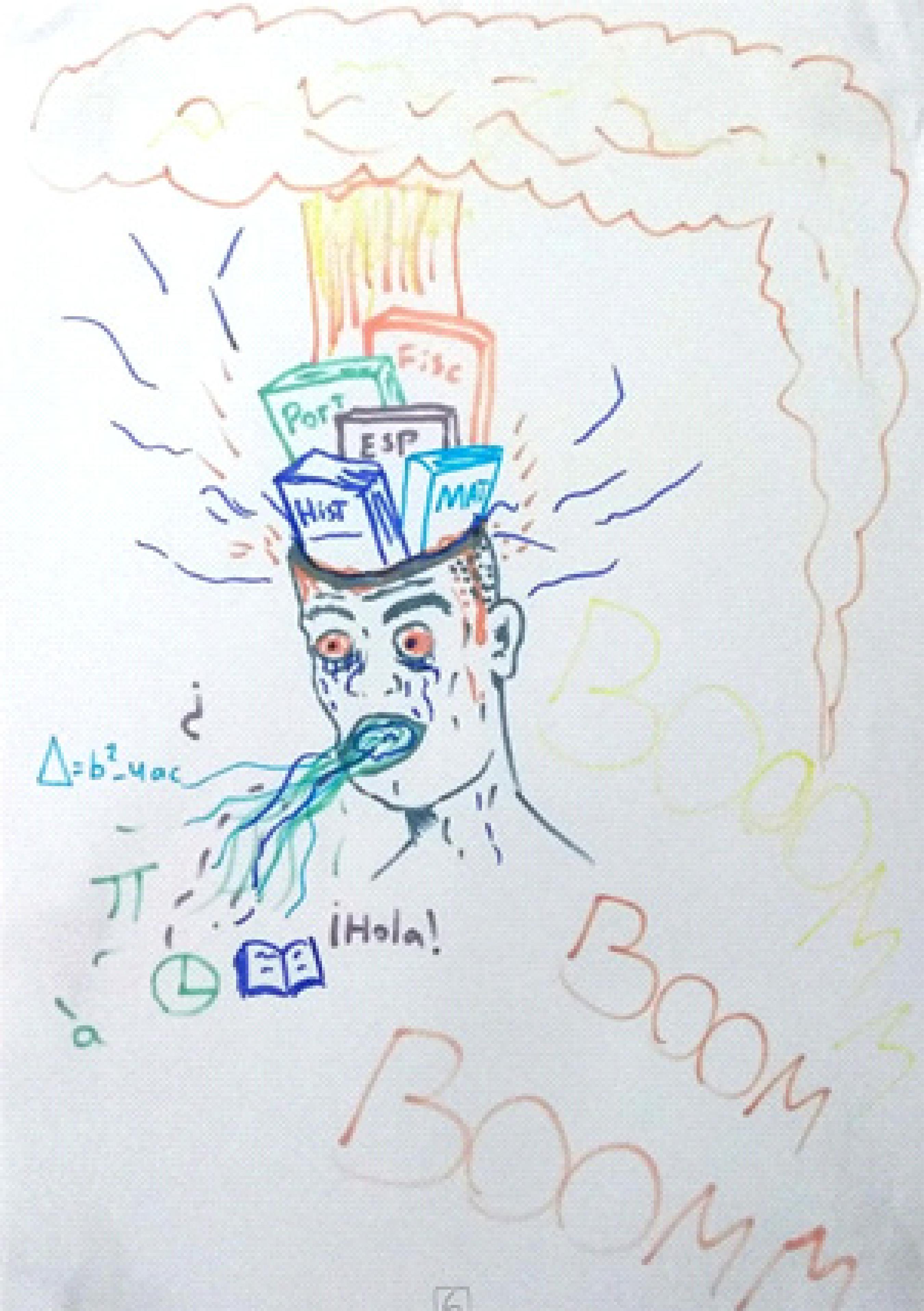

These indications signal aspects of the schooling process that should be more emphasized in the school day-to-day. For those who defend a humanist perspective of education, it is not surprising that most students highlight the human, relational, and group issues provided by the school and enlarge its strict meaning as a teaching and learning place. In this sense, when asked to represent the place the school occupies in their lives, some students have explicitly drawn the changes they would like to see at school. Only two drawings are presented here. The first one highlights the effects of the current model of education, cognitive and focused on preparing for ENEM, on High School students (Figure 1).

Source: C3E6, Belo Horizonte/MG (2020).

Figure 1 Effects of the standardized school model on students.

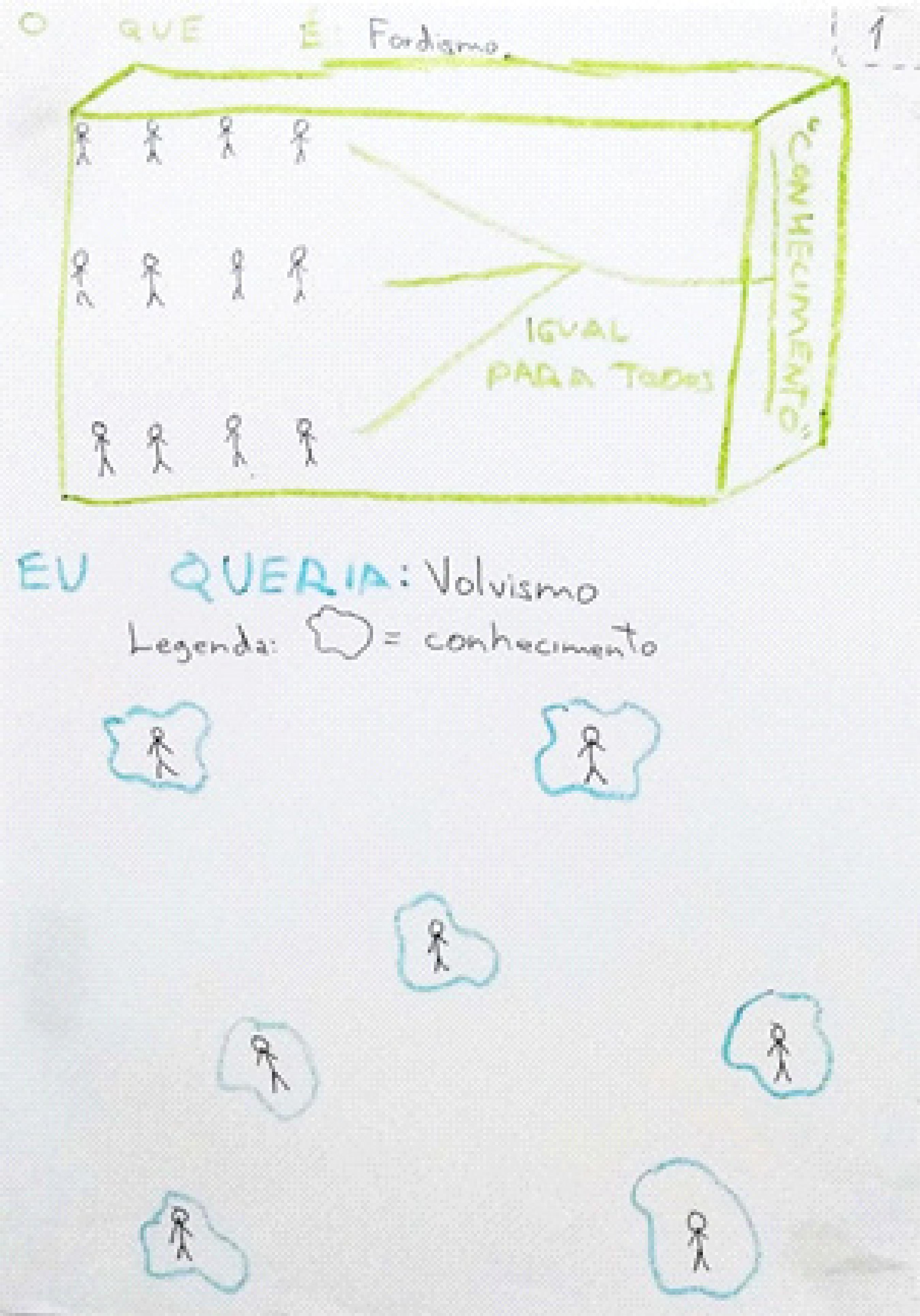

The student graphically indicates the emphasis on the segmented organization of knowledge; the banking transmission of the contents, which will later be repeated unconsciously, as denounced by Freire (2011); and the teenager reduced to his or her rationality, without a body, without context, without a floor. Two students refer to structural changes. One claims that “a more flexible curriculum, the end of the Fordist teaching method and the implementation of certain methodologies would make school X a better school” (S1S9), the other draws a movement from the school currently based on the Fordist model, focused on mass schooling and the industrial model, in which “knowledge is the same for all”, towards a Volvist24 school, in which knowledge suits the needs of each individual (Figure 2).

Final Considerations

Students’ reports about their schooling experiences at the end of basic education reveal different perceptions of Catholic education, at the same time endorsing and problematizing the usual educational practices. Although all Catholic schools adopt the speech of integral formation, most students report cognitive education experiences focused on teachers transmitting standard contents and students obtaining good grades. The other dimensions of integral education, such as human formation, citizenship, group experiences, insertion in other realities, and elaboration of life projects, are mentioned only by students who participate in non-compulsory extra-class projects, especially those focused on volunteering and evangelization. Students whose school experience is restricted to the activities developed in the classroom – most of those involved in this research – tend to perceive a little contribution of the Catholic school to their life trajectory and decisions over future pathways.

Still regarding the perspective of integral formation, students confirm the rupture pointed out by Dubet and Martucelli between being a High School student and being a teenager. Adolescence, a fundamental period in human development, raises several issues that include the school, but are not restricted to it. If the space-time of the Catholic school disregards the formation of youth subjectivities and the personal and social experiences necessary for the constitution of students’ identities, teaching and learning processes are unlikely to achieve their purposes. An education disconnected from other dimensions of the students’ lives limits their possibilities of human, social, cultural, academic, and professional development, serving to keep tradition and stability better than to connect school, educators, and students with the changing contemporary world.

Students’ perceptions confirm several aspects education researchers and international documents on education today call for, such as the humanist vision, the preparation for social life, the dialogue with diversity, the use of new educational technologies, among others. They do not refer to the adoption of participative and innovative methodologies, probably because schools tend to reinforce the traditional model of content transmission instead of fostering flexible processes of teaching and learning and addressed to the student’s protagonism in the construction of knowledge. Relationships with teachers, classroom dynamics, curriculum, all tends to focus on the next stage of the students’ life, rather than involving their present lives and assigning meaning to the school education.

Finally, at least three different groups of perceptions about the experiences developed at the same school space-time are identified: most students see the educational institution for its strict function of transmitting the knowledge required for continuing their studies, and nothing more than that; others may report significant experiences taking place at the school, but without so many consequences for their present and future lives due the distance between the school and local and global realities; others still interpret their time at school as fundamental to their subjective constitution, way of being in the world, and future definitions. These express critical visions about the school, pointing out how helpful the institution is to their development but also identifying a plastered educational system focused more on reproduction than on creation.

There are many common points among the three groups of students, especially referring to the limits of the school education. The last one stands out as more assertive regarding the changes the contemporary context brings to the school. According to their vision, the school provides several educational experiences in between the extremes of the standard schooling and the integral formation described on its educational project, generally letting students choose how it will be. As a result, the educational project is not established as an institutional option to face the educational system but reinforces it and loses strength when competing with other educational possibilities. The current school dynamics, focused on the reproduction of stability with only a few concessions to the integral perspective of education, limits its role as one of the institutional circuits of socialization and sociability for individuals, including support for them to assign meaning to the school time and draw their own perspectives of the future. As this position tends to close the educational institution within itself, it makes it difficult to favor the dialogue between schooling processes and the contemporary context, as well as its effective contribution to prepare individuals to live in this world.