Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Cadernos de História da Educação

versão On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.19 no.1 Uberlândia jan./abr 2020 Epub 30-Mar-2020

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v19n1-2020-7

Dossiê: História e memória da EJA nas universidades brasileiras e portuguesas

History of youth and adult education in Portugal: young adults over 23 years old in higher education1

1Instituto Federal Goiano (Brasil) michelle.lima@ifgoiano.edu.br

2Agrupamento Escolar de Pombal (Portugal) isabel.smoio@gmail.com

3Universidade de Coimbra (Portugal) vieira@fpce.uc.pt

The entry and stay of young people in Portuguese universities has been the subject of discussion with the edition of Decree-Law no. 393-B/99, Decree-Law no. 49/2005 and Decree-Law no. 64/2006. From these decrees on, the Portuguese universities started to offer special competitions for the enrollment of students over 25 years old and, in 2005, for those over 23 who have completed only primary education. Given this reality, we seek in this article to investigate the history of access and permanence of young people and adults in Portuguese higher education. To do this, we performed a statistical cross-referencing of the special courses of the University of Coimbra with the bibliography on the subject, analyzing the academic trajectory and the impacts of this course on the training of young people over 23 years old who did not finish high school.

Keywords: Higher Education; Adults; History

O ingresso e a permanência dos jovens nas universidades portuguesas têm sido tema de discussão com a edição do Decreto-Lei n.º 393-B/99, Decreto-Lei n.º 49/2005 e Decreto-Lei n.º 64/2006. A partir desses decretos, as universidades portuguesas passaram a oferecer concurso especial para o ingresso de estudantes maiores de 25 anos e, em 2005, para maiores de 23 que tenham concluído apenas o ensino primário. Diante dessa realidade, buscamos neste artigo investigar a história do acesso e permanência de Jovens e Adultos no ensino superior português. Para tal, realizamos um cruzamento de dados estatísticos dos cursos especiais da Universidade de Coimbra com a bibliografia sobre o tema, analisando a trajetória acadêmica e os impactos desse curso na formação dos jovens maiores de 23 anos que não concluíram o ensino secundário.

Palavras-Chave: Ensino Superior; Adultos; História

La entrada y permanencia de los jóvenes en las universidades portuguesas han sido objeto de discusión con la publicación del Decreto-Ley 393-B / 99, Decreto-Ley 49/2005 y el Decreto Ley Nº 64/2006. A partir de estos decretos, las universidades portuguesas han estado ofreciendo concurso especial para la admisión de los estudiantes mayores de 25 años, y en 2005, a aquellos mayores de 23 años de edad que han completado estudios primarios. Ante esta realidad, en este artículo se pretende investigar la historia de jóvenes y adultos el acceso y permanencia en la educación superior portugués. Para ello, realizamos un cruce de datos estadísticos de los cursos especiales de la Universidad de Coimbra con la bibliografía sobre el tema, analizando la trayectoria académica y los impactos de ese curso en la formación de los jóvenes mayores de 23 años que no concluyeron la enseñanza secundaria.

Palabras clave: Enseñanza Superior; Adultos; Historia

Introduction

Portugal is ranked among the first places in Europe concerning youth’s early leaving from education and training. According to data from 2016, 17.4 percent of men and 10.5 percent of women with ages from 18 to 24 years old quited their studies without graduating from high school. This gap in their education would fataly impede them to access higher education. Nevertheless, the entry and stay of young people in Portuguese universities has been the subject of discussion with the publication of Decree-Law no. 393-B/99 from 2nd October 1999. From that decree onwards, the Portuguese universities started to offer a special competition for the admission of students who had only completed primary education. The discussion mentioned is part of the concerns shared by the group of European countries to which Portugal belongs.

In June 1999, in the city of Bologna, an agreement was signed by 29 European countries. This agreement became known as the Bologna Declaration and its main aim was to strengthen and promote higher education in Europe. The Declaration proposed changes in the access to and attendance in higher education. One of them, that was important, is the recognition of the knowledge of the applicants to higher education institutions and the special regime for working students. These changes help the entry, attendance and stay of adults over 23 years old in higher education courses and everything became easier by means of the Basic Law of the Portuguese Education System (LBSE), whose article 12, subparagraph 4 states that “The Portuguese government should create the conditions to ensure citizens the possibility to attend higher education, in order to prevent the discriminatory effects resulting from the economic and regional inequalities or the previous social disadvantages” (PORTUGAL, 1986).

The Declaration of Bologna has significantly transformed the history of access to the Portuguese Higher Education. The increase in the number of students over 23 years old was significantly evident in the Universities from 2006 onwards. Under this system, such applicants, even if they were not holders of an access qualification to Higher Education, that is, without a graduation from high school (12th grade), may take the exams to assess their competences and abilities aimed at the attendance of that level of education.

In 2006 the Decree-Law no. 64/2006, from 21st March, assigned to the University of Coimbra the responsibility of managing the special exams for students over 23 years old.

The analysis of the data from the Statistics Directorate-General for Education and Science (DGEEC) about the access of these students to higher education has shown that in 2006 the numbers have increased. In 1988, 14.5 percent of the male population over 18 years old were enrolled at higher education institutions, and this percentage increased to 48.9 percent in 2006. With regard to the female population, the enrolment rate increased from 18 percent in 1988 to 61.1 percent in 2006. A relevant data is that until 2006 the number of women enrolled increased and subsequently it decreased gradually to almost 58 percent whereas concerning men that rate increased after 2006 reaching 52.5 percent. In spite of this decrease, there are still more women than men enrolled at higher education institutions.

Based on this context, we will present the history of the access of students over 23 years old to higher education (Law no. 49/2005), by discoursing on the historical trajectory of the specific exams and the autonomy of universities to carry them out.

According to the opinion of Ludke and André (1986), the accomplishment of a research demands a comparison between data based on a defined problem that disturbs the researcher. Thus, the methodology used in this research passes by the historical research and comprises the reading and analysis of bibliographic sources, newspaper texts, analysis of education reports and statistics on the access to higher education. On the whole, there is not a single methodology because the analysis of the sources may be defined by their own characteristics as well.

In terms of the methodology, this work included the use of different sources, among which was the documental source that, according to Gil (2002), “draws on documents that were not analysed yet, or that may be still re-elaborated in accordance with the objectives of the research. With regard to the sources, they are diverse and diffuse” (GIL, 2002, p. 45).

We searched the little evidence in the history of Portuguese education in order to understand how the Decree-Law, that established the special assessment to access higher education for students over 23 years old, was created and implemented. From this perspective, the method of the indicia paradigm2 may play an important part in this work because his commitment to the revealing detail establishes the dialogue between the part and the whole and safeguards the researcher from falling into the trap of the positivist description.

History of Adults’ Education in Portugal

Education in Portugal was under the precepts of the Company of Jesus during the 16th and 17th Centuries because it created and maintained different colleges in which education was free of charge in the whole country. That model of education was brought into ruin only in the 18th Century after the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal and the reforms of the Marquis of Pombal. These reforms caused the statization of education and in 1759 they put all classes under the royal authority (aulas régias). Primary education arose from these classes and it became compulsory during the Portuguese First Republic only in terms of legislation, since its legal enforcement was only implemented during the Portuguese New State.

In the history of Portuguese education, teaching was divided between the Church and the State, but from the Marquis of Pombal reforms onwards, the State gradually took control of formal education by announcing the principles of an educational system managed, coordinated and financed by the State. Nevertheless, during the reign of queen D. Maria I (Mary I), the coordination of education was in the hands of the Church once again. Therefore, education in Portugal underwent several changes and reforms, but this paper will focus on the period from 1888 onwards when the creation of adults’ education was designed. During the New State, from 1926 to 1974, there was a great number of farms and families that lived and worked in rural areas and, for parents, the education of their children at high school was not important. Many parents let their children attend school only during primary education because they had to work on the farm and help with the tasks and farm maintenance. In Portugal, primary education became relatively compulsory during the New State and many parents believed that their children only needed to learn how to read and write in order to deal with the family business. According to Neves (2018), his father “was an old-school father and an old-school boss. My siblings did not attend school but went to work the land. He had a place to work in agriculture and could sell everything he produced.” This narrative reveals a common thought in the Portuguese society during the New State. Parents believed that the best for their children was to take care of the farms and the land. This way of viewing education caused a high level of illiterate adults or with a low level of schooling by that time.

In Portugal youth and adults’ education is identified as adults’ education and, despite being a recent phenomenon, it is not new. If we regard “education as a wide and multiform process that merges with the process of life of each individual, then it is obvious that adults’ education has always existed” (Canário, 2008, p. 12). After the French Revolution the concern with literacy of adults became obvious and education was understood as a chance of minimising social injustices. In doing this, the French State assumed the responsibility to fight against illiteracy and influenced other European countries, including Portugal.

During the Constitutional Monarchy period (1820-1910), the reform by Passos Manuel stood out in 1836. The set of reforms published by Passos Manuel was a milestone in Portuguese education. For example, he is known for a series of measures to promote education in Portugal at all its levels (CARVALHO, 1986). However, the reforms were not implemented which is confirmed by the high level of illiteracy, that in 1850 was 85 percent and in 1900 was 75 percent. In 1950 this level was still high, reaching approximately 45 percent.

In the face of a context of high illiteracy with an impact on the skilled workforce, the Portuguese Minister of Education, Fernando Andrade Pires de Lima, who was member of the government for eight years (1947 a 1955), realised the lack of skilled workforce to meet the technological advances that had emerged after the Second World War.

In Portugal primary education became compulsory in 1956 for males (children or adults) and in 1960 for girls. In the meantime, illiteracy was a structural problem and declined slowly without being subject to a great influence of the administrative and political deliberations. Thus, the concern with, and the idea of, adults’ education grew stronger after the French Revolution and stabilised after the Second World War in an orderly manner by means of the State. From that moment onwards, adults’ education solidified by means of popular initiatives with the support of non-governmental organizations. Education became seen as directly related to economic issues of the country, and it caused its adaptation to the development management, changing the social reality of those adults without schooling. Within that context, education emerged as an attempt to solve the problems of modern society and rested upon the social movements as a magical solution for the existing social instability.

The attempts concerning adults’ education, mainly in the First Republic, were contingent and related to social and religious movements with a welfare characteristic. In spite of the supervision of the State, the measures focused on Adults’ Education had welfare, educational and doctrinal characteristics.

During the New State, Portugal was under a dictatorship known as Salazar period. There was an imbalance in the field of education and the country underwent an authoritarian moment based on the ideological trilogy “God, Homeland and Family”. The State gave great importance to norms, attitudes and values. There was an overvaluation of the homeland and values related to the patriarchal and macho family. We have realised also the adequation of the school offer to the social structure which is characteristic

[...] of a traditional society, in order to use the school system - based on the horizontal extension of the “short” primary education and the systematic dissuasion from aspirations to upward social mobility by means of the attendance of non-elementary school levels - as an instrument for the integration of social order through the resignation of each individual to his/her status. (SILVA, 1990, p. 17-18). [Our translation]

The New State expressed its concern with adults’ education during the 1950’s, when some campaigns were launched to eradicate illiteracy. The Portuguese State intervened in education by means of the Decree-Law no. 38968 and Decree-Law no. 38969 that were promulgated by the Minister Pires de Lima. The first Decree-Law refers to the Popular Education Plan and the second refers to the National Campaign of Adults’ Education.

The National Campaign of Adults’ Education (CNEA) and the Popular Education Plan

In 1952, during the New State, the government proposed the Popular Education Plan and the National Campaign of Adults’ Education. Portugal underwent an economic restructuring with the progressive replacement of the agrarian economy by the establishment of industries. The new economic model required from the state a restructuring within the scope of education because skilled workforce was necessary to work and develop the industries.

On the other hand, creating serious difficulties for the illiterate regarding their admission to work in any public or private entities, it would not make any sense that, at the same time, these individuals would not get the chance of receiving education at courses duly organised and free of charge. (PORTUGAL, 1952, p. 1078). [Our translation]

In this regard, on 27th October 1952 the Decree-Law no. 38968 was promulgated, which reinforced the compulsoriness of elementary primary education and created the courses for adults’ education thus promoting the national campaign against illiteracy.

Since it does not seem reasonable that the State continues to maintain only evening courses, then it is established that these courses may take place during the day or at night, in accordance with the demands of the education interests.

Consequently, the action of the courses is expanded, which will bring great advantages mainly to the education of illiterate girls and women to whom night school is not, in any way, advised and, in the majority of the cases is not possible.

For all these reasons, and because it is important to give an educational sense to the courses, then they get the wider designation of “courses for adults’ education”. (PORTUGAL, 1952, p. 1078). [Our translation]

The Decree-Law no. 38968, by approaching the Popular Education Plan, presents a retrospect of adults’ education in Portugal:

It is fair to say that since the establishment of primary education in 1772, rulers frequently committed themselves to finding a solution for the problem of popular education.

In the long history of Portuguese primary education there are plenty different legislative measures with which some governments intended to foster the culture of our people.

The restructuring of the teaching plans in the primary education from 1870, 1878, 1884, 1901, 1911 and 1919, and many other reforms of primary school, demonstrate that it was not due to the lack of legislation that the problems in elementary culture did not find the proper solutions.

Who studies this high volume of legislation, and is aware of the political and social constraints of that time, will understand that initiatives, so many times inspired by the best mood to serve education well, did not bring the desired benefits to the cause of popular education. On the one hand, the political instability and the insufficiency of financial resource, on the other hand the study of the issues mainly in theory, forgetting the realities, the discontinuity of action, the constant change of guidelines, a series of contradictory laws concerning its principles and details, after all, the lack of a consistent public education policy, explain the failure of the different reforms in primary education that were tried until 1926. (Decree-Law no. 38968, p. 67). [Our translation]

The Portuguese government fought against illiteracy and, during the New State, the biggest educational investment was not in adults’ education but rather in the education of children between seven and 12 years old. The Decree-Law no. 38968 from 1952 stated that in order to ensure the compulsoriness of primary education, a system of fines was established for the individuals responsible for children that did not ensure their access to primary education. Therefore, in order to achieve the objective of reducing illiteracy in Portugal,

[...] a new system of fines had to be established. It was assumed that parents/guardians who do not comply with their responsibilities, must be punished. [...]. The entities charged with the task of promoting or implementing it only need to realise the special responsibilities that are assigned to them in order to solve one of the most serious national problems that is the eradication of illiteracy. If the fines are not payed voluntarily, they will be applied by the judicial court within a process of transgression. Great possibilities of defence are given to the transgressor but if he/she is condemned, he/she will not escape the fulfilment of the sentence because, if he/she does not pay the imposed fine, it will be replaced by imprisonment or by the provision of work on public works. (Decree-Law no. 38968, p. 71).

From that Decree onwards, another Decree, with no. 38969, was published which in its first Chapter establishes the compulsoriness of education. All children between seven and 12 years old should have access to primary education until their successful assessment in the elementary education’s exam.

Besides the compulsoriness of primary education, the government established some measures to reinforce it, such as: prohibition of hiring people to the permanent staff who are under 18 years old and had not taken the exam of the elementary primary education; prohibition of the Portuguese citizen to enter certain jobs by means of the dispatch of the Minister of Corporations and Social Welfare; a fine for those who infringe the law; holding the 3rd grade of primary education as a requirement for working in the permanent staff of public services; prohibition of taking the driving license exam if individuals did not hold at least the 3rd grade of primary education; prohibition of emigrating if individuals were between 14 and 35 years old and had an unsuccessful assessment in the primary education’s exam, excepting wives accompanying their husbands or individuals in need of care. It is worth enhancing that married women accompanying their husbands could emigrate without having primary education.

The Decree-Law no. 38969, from its article 17 to article 27 approaches the courses for adults and its article 23 created the National Campaign Against Illiteracy. Article 26 established a National Fund for Adults’ Education aimed at the expenses of that Campaign.

The courses of adults’ education, aimed at adolescents and illiterate adults, may be created at the initiative of the Ministry of Education or by request of any public or private institution. Therefore, in 1952 there were campaigns and legislation from the Government to eradicate illiteracy in Portugal that reflected the doctrinal vision of the New State.

The New State gives great importance to education’s issues and defines, from the very beginning, policies that characterised school as the privileged space of indoctrination and social integration. The protection of the value education includes a criticism to the republican logic of instruction (although both systems know that the one term does not exclude the other): by reissuing this dichotomy, the State tries to justify its strategy of reduction and simplification of school learnings and its strategy of reinforcement of the religious and moral components. (NÓVOA, 1999, p. 591). [Our translation]

Consequently, besides the illiteracy indices, the Government of the New State, regarding education, sought to fix the hegemonic values characteristic of the current political system. According to Nóvoa (1999),

The educational ideology of Salazar has as reference the tradition and unchangeable values that impose themselves as a totalising dimension of the social representations and a discourse that legitimates the political and programmatic decisions [...] Based on the appeal to the customs of the Portuguese families, the Christian practices and the popular beliefs and cultures, the New State reinvents an ideology strongly integrative or, in other words, it appropriates a certain reality and transforms it into an ideology. (NÓVOA, 1999, p. 591). [Our translation]

By means of the administrative system in the National Campaign of Adults’ Education, the government improved its bureaucratic and consolidating legacy, thus sharing the functions concerning the Campaign (CNEA) between the Nacional Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Corporations and Social Welfare.

The CNEA began in 1952 with the aim of urging the population to overcome the barriers of illiteracy and to the necessity of getting the participation of the private sector along with the Portuguese State to disseminate popular culture. However, the CNEA stuck to the process of literacy by means of the dissemination of the knowledge of reading, writing and the offer of a basic level of schooling for illiterate people. Later on, in 1953, the Campaign adopted an ideological slant and disseminated “notions of moral, civic, familial and sanitary education, education of corporative organization and welfare, agriculture and livestock education, homeland history” (ADÃO, 1999, p. 600).

Adults’ Education during and after the 1974 Revolution

Although in 1971 a Central Structure had already been created - Permanent Education General-Directorate - to lead literacy actions and the courses of Adults’ Education, the truth is that until 25th April 1974 this area remained without an historic past in terms of conceptualisation (Melo et al., 1998). That situation caused the beginning of a new historic period in Portugal without a firmly rooted public policy of Adults’ Education. Consequently, Alcoforado (2008) refers that Portugal reaches the second half of the 1980’s without a true capacity for solving the fundamental problems within the scope of adults’ education “but , maybe even more serious, without revealing the talent to find competent public policies and without showing the art of establishing a network with sufficient dynamics to mobilise wills and resources” (ALCOFORADO, 2008, p. 220).

On 25th April 1974 the Revolution of the Carnations took place, aiming at establishing democracy by establishing great social changes, which ousted the system of Salazar in Portugal. After the 1974 Revolution the revolutionary period, known as Ongoing Revolutionary Process - PREC, was established and it ended in 1976 when the Portuguese Constitution was approved. This period was important for the democratisation of Education because it presented new proposals, since the reform of Veiga Simão was never implemented with the revolution. With regard to Adults’ education

[...] in the last decades, it reveals a field deeply characterised by discontinued education policies. Having no tradition to evoke or update in the presence of a history characterised by the detachment of the political and cultural elites from the basic education of their fellow citizens, as well as the absence of big educational institutions or social movements with an impact on the education of adult population, the democratic system would be confronted with the necessity of reinventing policies of adults’ education by giving them a greater emphasis within the scope of public policies, and especially by building a sector and a public offer able to face a clearly serious social-educational situation. It is important to remember that in the 1970’s about a quarter of the Portuguese population was illiterate, the schooling rates of children and youth were extremely low and, notwithstanding the increments implemented from the previous decade onwards, university population was sparse. (LIMA, 2005, p. 31).

Before this political context of democratisation in the country, with a greater openness to social transformations, adults’ education achieved another level when it relied on policies of criticism education (Lima, 2008), from a drastic changeover in the way education was meant. Accordingly, the State implemented a partnership with the civil society by means of popular associations, providing new options of adults’ education aiming at the promotion of social justice through substantial transformations in society. According to Guimarães and Barros (2015), that agreement with new practices aimed at the promotion of the critical and emancipatory reflexion.

Popular education boosted by this cooperation beneficiated large sectors of the population in a context in which about a quarter of the population was illiterate. It is important to highlight that, according to the population census carried out in 1970, 49.8 percent of the Portuguese population which was 14 or over 14 years old did not have nor attended the elementary primary education.

In 1976 the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic was written by the Constitutional Assembly elected after the free general elections in the country on 25th April 1975. The Constitution came into force on 25th April 1976 with a strong socialising feeling. In its article 73, it stated that:

Everyone has the right to education and culture.

The State will promote democratisation of education and the conditions for education, that is carried out by means of school and other training means, to contribute to the development of the personality and the progress of democratic and socialist society.

The State will promote democratisation of culture, encouraging and ensuring the access of all citizens, especially workers, to the enjoyment and creation of culture by means of basic popular organisations, societies of culture and entertainment, the media and other adequate means. (PORTUGAL, 1976).

Among other issues, the Constitution established that the State has the responsibility of democratising education by means of dynamization of different educative modalities (formal and non-formal) in search of equal opportunity for overcoming economic, social and cultural inequalities aiming at the personal and social development of citizens.

By the end of 1970’s, Law no. 3 from 10th January 1979 called “Eradication of Illiteracy” granted the State the responsibility for elaborating the National Plan of Literacy and Basic Education of Adults - PNAEBA.

1 - Under the Constitution, the role of the State is to ensure universal basic education and eradicate illiteracy.

2 - The initiative of the State must be implemented by means of the joint action of the organs of central and local administration, observing the principle of administrative decentralisation.

3 - The State recognises and supports the existing initiatives regarding literacy and basic education of adults, namely those of popular education associations, societies of culture and entertainment, cultural cooperatives, popular organizations based on the territory, labour unions, workers’ commissions and confessional organisations. (PORTUGAL, 1979, p. 35).

The Law previously mentioned comprises literacy and basic education by means of the personal development of adults and their gradual integration in the cultural, social and political life, seeking for a democratic and emancipated society. Therefore, the process of literacy was developed by projects of formal and non-formal education relevant for adults. From Law no. 3/79 onwards, a curriculum was established which integrated adults from different levels of compulsory schooling, excepting the elementary basic education.

By entwining popular education with basic education between 1974 and 1980, adults’ education became comprehensive regarding the right to education within public policies. Nevertheless, these policies were fragile in practice, though the documents were leading to the idea of widening the right to education.

Based on the modernisation and state control, from the 1980’s onwards there was a resumption of school rules according to the centralised control of education which caused the reduction of the field of adults’ education. Consequently, adults’ education, known as recurrent education, underwent a progressive formalisation. That movement that was implemented in Law no. 3 from 1979 (Eradication of Illiteracy), states that the State has the function of ensuring universal basic education and eradicate illiteracy, and that the Government has the responsibility of:

a) elaborating the National Plan of Literacy and Basic Education for Adults and promoting its publication and implementation, and collaboration with the organs established by the current law; b) including in the draft laws of the State’s General Budget the funds necessary to the implementation of the current Law (article 10) (PORTUGAL, 1979, p. 37). [Our translation]

The Law of Eradication of Illiteracy marked the change from the social educational movement to the trial of a governmental organisation of adults’ education with social and democratic characteristics.

The idea presented by Law no. 3 from 1979 was interesting insofar that it increased social educational potential by establishing a partnership between the State and non-governmental associations and presented an autonomous and decentralised system of adults’ education. In 1980 the national Plan of Literacy and Basic Education of Adults, which was proposed in article 4 of Law no. 3, was neglected by the government and the support of the Ministry of Education became inexpressive in relation to popular education, associative activities and community intervention.

Under this perspective of construction of an education system, in 1986 the Basic Law of the Portuguese Education System was approved - Law no. 46/86. Such Law organised adults’ education based on two proposals: recurrent education and extra-school education. The former, was characterised by its extent, involving more students, teachers and public schools. The State, by means of the Ministry of Education, in its search for promotion of equal opportunity for educational access and efficacy, took possession of a fundamental role in the development of adults’ education, especially in the creation and promotion of educational contexts and practices, such as pedagogical methods, follow up and assessment. Extra-school education was implemented by non-governmental organisations by means of activities integrated in activities of community intervention. Understood as a liberal adults’ education, it was less important concerning the human resources and materials that were spent.

The Basic Law limited also the field of adults’ education and proposed a new understanding of citizenship focusing on the disciplinary knowledge transfer and a range of knowledge acquired in the classroom. Accordingly, adults’ education played its role regarding the search for development and modernisation of the country.

History of access to University for persons over 23 years old

As already mentioned, nothing much has happened in the public policies of adults’ education and training in Portugal until the promulgation of Law no. 5/73 from 25th July - on the initiative of the Minister Veiga Simão, and known as the “Reform of Veiga Simão - that “provided for that the educational system should comprise the pre-school education, school education, and permanent education, being organised in an integrated and global way, and observing completely (and this was an absolute legislative novelty) the principle of democratisation of education” (Alcoforado, 2008, p. 215). In fact, the last Minister of Education of the New State, Veiga Simão, had the role to begin the process of modernisation that is the genesis of the current organisation of the Portuguese Higher Education (Teodoro, Galego, Marques, 2010). This Reform aimed at the increase in the attendance at Higher Education, focusing on the meritocratic discourse which mobilised the aspirations of all those who wanted to access it (Brás et al., 2012). Furthermore, it aimed also at the expansion and diversification of Higher Education, trying to meet the training needs of the qualified human resources adequate to the process of economic development (Castro et al,. 2010).

The plan of expansion and diversification of Higher Education, approved by the Decree-Law no. 402/73 from 11th August, provided for the creation of three new Universities (New University of Lisbon, University of Minho and University of Aveiro), the University Institute of Évora, Polytechnic Institutes (in Covilhã, Vila Real, Faro and Leiria) and Normal Higher Education Schools (Beja, Bragança, Castelo Branco, Funchal, Guarda, Lisboa, Ponta Delgada, Portalegre and Viseu) (Brás et al., 2012). This Decree-Law expresses the intention of extending the network of Higher Education Institutions. Therefore, it is legitimate to consider that the political action of Veiga Simão “represented undoubtedly a period of mobilisation of wills and predispositions that put Higher Education at the very core of debates on development and modernisation of the country” (Teodoro, Galego, Marques, 2010, p. 664). The political action intended by Veiga Simão represented therefore a period of mobilisation of wills by investing in education as a factor of development and modernisation.

Nevertheless, the Revolution of April 1974, by revoking the Law no. 5/73, abandoned some of the most relevant measures of Veiga Simão (Brás et al., 2012). As a result, “the Second Interim Government made for the definition of an educational policy that was not dependent from the continuity of the expansionist reform designed by Veiga Simão during the last years of dictatorship” (Ferreira, Seixas, 2006, p.258). Consequently, this action caused the clear abandonment of the implementation of that Law and the suspension of different measures regarding the expansion and reorganisation of Higher Education.

On that account, with the end of the New State, the Law of Veiga Simão expired and was never regulated, and all the options stated by that law were abandoned which prompted the necessity of a new Basic Law of Education System (Pires, 1987). This necessity and social conscience that it was urgent to stabilise and clarify the organisation of the Portuguese education system were assumed as two strong reasons to boost the elaboration and approval of Law no. 46/86 from 14th October which governed the education system in Portugal from then on.

Although it is not our purpose to approach all the structuring axes and changes of that Law, it would not be wise to proceed without referring to that this law already established that individuals over 25 years old, who did not hold a high school degree, or a similar one, could take an adequate exam of ability to attend higher education (article 12), which would be national and specific for each course or group of similar courses (article 13).

Since then, Higher Education has been growing progressively and showing a centrality in the life path of an increasing number of citizens, as well as in the development strategies of societies, States and supranational organisations (as the EU) (Alves; Pires, 2009).

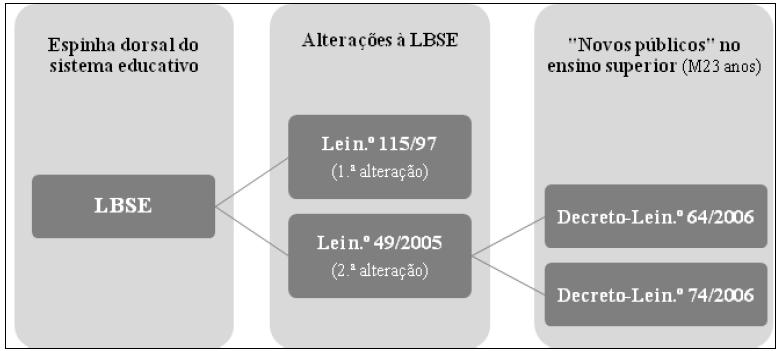

Between 1986 and 2006 two changes were produced, both with a predominant influence on Higher Education concerning policies of the higher education cycles of studies (cf. Image 01).

Source: MOIO, I. Reconhecimento de Competências no Ensino Superior: uma realidade reconhecida ou a reconhecer? PhD Thesis (unpublished). Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra, 2017.

Image 01 Changes to the Basic Law of Education System (LBSE) and norms for individuals over 23 years old.

The first change to the Basic Law of Education System was made by the Law no. 115/97, from 19th September, which in its article 12 refers to that the State is responsible for ensuring the elimination of global quantitative restrictions on access to Higher Education, as well as promoting “conditions so that the existing courses and the ones to be created correspond globally to necessities of qualified personnel, the individual aspirations and the increase of the educational, cultural and scientific level of the country” (pp. 5082-5083) and that “the individuals over 25 years old, who do not hold a high school degree course, or a similar one, and do not hold a higher education degree, should take an exam, especially adequate, of ability to attendance at it” (idem, p. 5083) have access to Higher Education.

However, it was only almost two decades after its publication that the Basic Law of Education System was subject to an important change (by means of the Law no. 49/2005, from 30th August), with a substantial impact due to the fact that it established the foundations to create the conditions aiming the implementation of the Bologna Process, all this after the approval of the principles regulatory of instruments to create the European Higher Education Area (Ferreira, 2006) by the Decree-Law no. 42/2005, from 22nd February.

The changes covered by the Law no. 49/2005 - that reduced the age of admission to higher education to 23 years old - aim at “promoting the attendance at higher education, improving its quality and relevance, and fostering mobility and employability of its graduates in the European area” (Correia; Mesquita, 2006, p. 171). This change in the access system to higher education, by means of special access competitions, by reducing the age from 25 to 23 years old, and, above all, by granting institutional autonomy in the selection processes, aims at increasing the number of students that reach higher education cycles of studies by means of this competition (Castro et al., 2010).

Thus, that Law was important for having confirmed the creation of conditions so that all citizens could access lifelong learning, by changing the conditions of access to higher education for those who did not enter it during the reference age and the normal means of access, by giving higher education institutions the responsibility for these individuals’ selection and by creating the conditions for the recognition of the professional experience.

Under these circumstances, in Portugal, within the scope of the changes introduced by the paradigm of lifelong (and in every spaces) learning and the Bologna Process, there was the need for “approval of the rules that could facilitate and soften admission and access to higher education, namely for students who were under specific qualification conditions” (Monteiro et al., 2015, p. 133). Therefore, concerning the participation of adults in Higher Education, specific measures were taken regarding the admission processes. Initiatives worth mentioning are those implemented under the Decree-Law no. 64/2006, from 21st March (a regulation that gave each institution the responsibility for the admission to higher education cycles of studies and regulates the adequate exams to assess the ability of adults over 23 years old to attend them - for this reason it is usually called M23 years old), and under the Decree-Law no. 74/2006, from 24th March (that establishes the legal regime of the degrees and diplomas in higher education and the new model of organisation of the cycles of studies developed within the scope of the Bologna Process, thus formalising the implementation of that Process in Portugal).

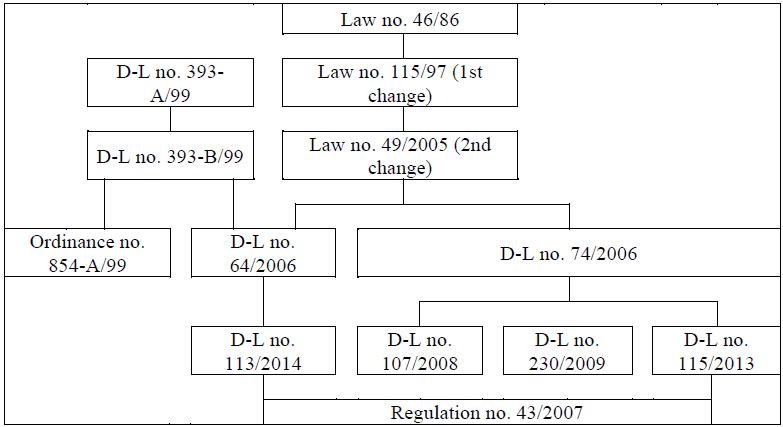

Accordingly, those regulations promote the extension of the access of “new audiences” to higher education and recognise professional experience for the purpose of admission and academic progression, whose “genealogic tree” we present in image 02, since we consider that understanding genealogy of most recent policies implies not only to invoke the most immediate antecedents ,but also a general vision of the range of policies regarding “new audiences” in higher education in the last trimester of the 20th Century.

Source: MOIO, I. Reconhecimento de Competências no Ensino Superior: uma realidade reconhecida ou a reconhecer? PhD Thesis (unpublished). Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Coimbra, 2017.

Image 02 “Genealogic Tree” of regulatory documents

We may consider, then, that filiation of the Decree-Law no. 74/2006 is Law no. 49/2005 (second change to the LBSE); in what Decree-Law no. º 64/2006 is concerned, it inherited the genes from Decree-Law no. 393-B/99 (that regulates the special competitions of access and admission in higher education aimed at students who have the specific qualification conditions - holders of the special exam of assessment of ability to access higher education for individuals over 25 years old, holders of a higher education degree, post-high-school and medium degrees and students from foreign higher education systems) on one hand, and the Law no. 49/2005 on the other hand.

We confirmed also that Decree-Law no. 64/2006 shares its filiation with Ordinance no. 854-A/99, that establishes the regulation of special competitions of access to higher education, which article 20 from Decree- Law no. 393-B/993 refers to.

From that genetic combinations emerges Regulation no. 43/2007 - Regulation of the Exams Especially Adequate aimed at assessing the ability to attend higher education of students over 23 years old at the University of Coimbra - since, as laid down in article 14 of Decree-Law no. 64/2006, the legal and by-law competent organ of each higher education institution is responsible for elaborating and approve the regulation of that exams, according to paragraph 5 of article 12 in Law no. 46/86.

We can state, then, that the process of M23 years old promotes access to higher education in Portugal of people over that age, not holding an access qualification4,but who show competences to attend it.

The Decree-Law no. 64/2006 established, according to the point of view of Brás et al. (2012), the promotion of equal opportunity in the access to higher education, breaking with what was considered to be an historic elitism. However, Alves and Pires (2009) remind that it is necessary to analyse the Portuguese higher education, and particularly the way it has evolved and met (or not) one of its usual expectations: the promotion of equal opportunity.

According to Magalhães et al. (2009), the current situation corresponds to the third period of development of Portuguese policies of access to higher education, called “more but different”, which represents, in the authors’ opinion, the change from equality to equity and from quantity to quality, as well as the diversification of the training offer and a focus on more diverse audiences5.

Still in 2006, within the framework of massification of higher education, with the Decree-Law no. 74/2006, the discourse on quality became established and a break with education’s paradigm was evinced, replacing it by learning’s paradigm (Leite; Ramos, 2014).

Taking into consideration that legislation refers to two distinct, but complementary, aspects concerning recognition of adults’ experience in higher education (on one hand access, and on the other hand the advanced placement in the cycle of studies by means of credits), its legal framework seems to reflect, according to Pires (2007, p. 12) “an innovative logics that consists of the recognition of experience and training obtained or accomplished outside the traditional contexts of education by means of academic credits”

Nevertheless, new legislation may be interpreted from a continuity perspective since previously it was already possible to access higher education by means of a special exam (usually called “ad-hoc”, cf. Decree-Law no. 198/79, from 29th June6). Therefore, this was not the first time that in Portugal adults had access to higher education (Amorim, Azevedo, Coimbra, 2011). For that reason, in the opinion of Pires (2007, p. 12) “what seems to emerge as an innovation in Portuguese higher education is the possibility to recognise professional experience and training (in a broad sense) of the applicants, acting upon the grant of credits within the scope of cycle of studies”. Consequently, the same author (2010) refers to that, besides the national legal framework, it is essential that there is political will at an institutional level - creating the necessary conditions and resources - and the actors participate, promoting new spaces of intervention at the organisational level.

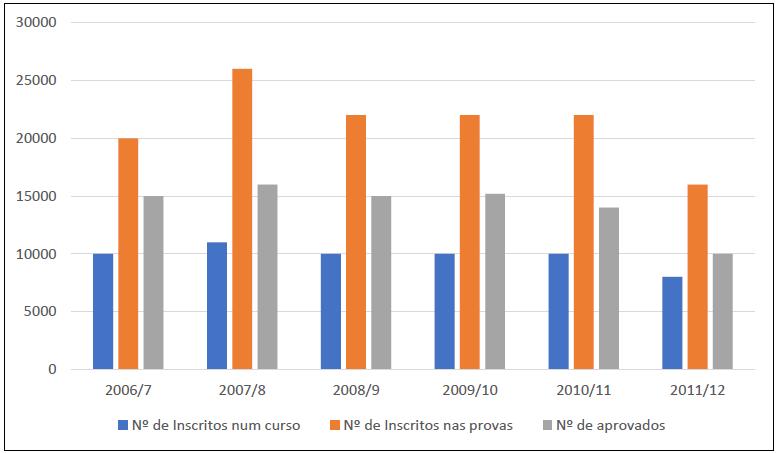

According to the data of DGEEC, the number of students registered for the exams is bigger than the number of students that enrol in higher education courses, as seen in the following chart:

Source: DGEEC - Survey concerning the especially adequate exams to assess the ability to attend higher education for individuals over 23 years old.

Image 03 Number of students registered in higher education via the competition for individuals over 23 years old and number of students registered and successfully assessed in the exams, 2006/2007-2011/2012

The Draft Law no. 49/2005 was meant to ensure access to higher education of adults over 23 years old, who had not attended basic education, thus assessing their knowledge and experience in accordance with the chosen course. In 2006, by means of the Decree-Law no. 64, freedom was given to higher education institutions to organise and establish how the assessments of recognition and validation of experience knowledges would be, concerning adults over 23 years old who did not complete the 12th grade. This caused a discrepancy between the number of students admitted to public higher education and those admitted to private higher education.

Final Considerations

The history of Portuguese education presented here shows that over the years there was a lack of interest in adults’ education, which changed progressively with the new political structure of Europe. Portugal’s entry in the European Union required some social and economic changes to minimise social and economic differences among the EU countries.

One of the measures taken by the Portuguese government to increase the level of schooling of the Portuguese population was to invest in processes of access to higher education for young people and adults who did not complete basic education. Therefore, when we talk about Education of Young People and Adults, we identify that one of the measures taken by the Portuguese government to give access to higher education to that young people was the Decree-Law no. 64/2006 which gives the possibility of access to higher education to individuals who did not complete basic education and are over 23 years old.

After analysing the data of access to higher education in the competitions for individuals over 23 years old we note that from 2006 onwards there was an increase in the percentage of students registered for these competitions, that increased from 20000 in 2006/2007 to 25000 in 2007/2008.

The number of students registered decreased in the academic year 2011/2012 to approximately 16000. According to the national data of access to higher education, 26 per cent of the candidates that registered for the exams of the competition for individuals over 23 years old did not complete the process of application.

Based on this study, in accord with the researches in the fields of history of education, we realised that both men and women that were admitted to higher education by means of the special exams have specific interests regarding access and stay in the classroom, such as issues related to occasional demands of the labour market.

Based on the data available in the DGEEC we realise that the number of adults registered for the special exams of access to higher education is considerably higher than the number of adults that reach the end of the exams and are admitted to a course. This leads us to question if the competition for individuals over 23 years old is being implemented in accordance with what is laid down in the law and if it really is facilitating access of non traditional adult students to higher education.

According to the data of DGEEC, there was an increase in the number of adults that did not complete the 12th grade of schooling enrolled in higher education. Nevertheless, when we analyse the number of those who register for the exams for individuals over 23 years old, we think that number should be higher.

REFERENCES

ADÃO, A. Educação de Adultos. In BARROS, A.; MÓNICA, M. F. (coord.). Dicionário de história de Portugal. Porto: Livraria Figueirinhas, vol. VII, 1999, p. 599 - 601. [ Links ]

ALCOFORADO, L. O modelo da competência e os adultos portugueses não qualificados. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia. v. 35(1). Coimbra, 2001, 67-83. [ Links ]

ALCOFORADO, L. Competências, cidadania e profissionalidade: limites e desafios para a construção de um modelo português de educação e formação de adultos. Dissertação de Doutoramento (não publicada). Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação, Universidade de Coimbra, 2008. [ Links ]

ALVES, M.; PIRES, A. L. Aprendizagem ao Longo da Vida e ensino superior: novos públicos, novas oportunidades? ANAIS - Unidade de Investigação Educação e Desenvolvimento, 9, 2009, p. 43-54. [ Links ]

AMORIM, J. P.; AZEVEDO, J.; COIMBRA, J. L. E depois do acesso (de “novos públicos” ao ensino superior): a revolução não acabou. In L., Alcoforado et al. (Orgs.), Educação e Formação de Adultos - Políticas, Práticas e Investigação (pp. 211-225). Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 2011. https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-0228-8_18 [ Links ]

BRÁS, J. V. et al. A universidade portuguesa: o abrir do fecho de acesso - o caso dos maiores de 23 anos. Revista Lusófona de Educação, 21. Lisboa: Portugal, 2012, p. 163-178. [ Links ]

CANÁRIO, R. Educação de Adultos. Um campo e uma problemática. Lisboa: Educa, 2008. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, R. História do Ensino em Portugal - desde a fundação da Nacionalidade até o fim do Regime de Salazar-Caetano. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1986. [ Links ]

CASTRO, A. et al. Políticas educativas em contextos globalizados: a expansão do ensino superior em Portugal e no Brasil. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 44(1). Coimbra, 2010, p. 37-61. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8614_44-1_2 [ Links ]

CORREIA, A. M.; MESQUITA, A. Novos Públicos no Ensino Superior - Desafios da Sociedade do Conhecimento. Lisboa: Edições Sílabo, 2006. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, A. G.; SEIXAS, A. M. Dimensões ideológicas em discursos político-educativos governamentais produzidos em Portugal nas duas últimas décadas do século XX. Estudos do Século XX, 6. Coimbra: Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX da Universidade de Coimbra - CEIS20. 2006, p. 255-282. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, J. B. Globalização e ensino superior: a discussão de Bolonha, Perspectiva, 24(1). Florianópolis - Santa Catarina: Editora UFSC, 2006, p. 229-242. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, P.; BARROS, R. A nova política pública de educação e formação de adultos em Portugal. Os educadores de adultos numa encruzilhada? Educação & Sociedade, 36(131). Campinas-SP, 2015, p. 391-406. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302015109444 [ Links ]

LEITE, C.; RAMOS, K. Políticas do Ensino Superior em Portugal na fase pós-Bolonha: implicações no desenvolvimento do currículo e das exigências ao exercício docente. Revista Lusófona de Educação, 27. Lisboa, 2014, p. 73-89. [ Links ]

LIMA, L. C. A educação de adultos em Portugal (1974-2004). R. Canário e B. Cabrito, Org. Educação e Formação de Adultos. Mutações e Convergências. Lisboa: EDUCA, 2005, p. 31-60. [ Links ]

LUDKE, M; ANDRÉ, M. D. Pesquisa em educação: abordagens qualitativas. São Paulo: EPU, 1986. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, A.; AMARAL, A.; TAVARES, O. Equity, access and institutional competition. Tertiary Education And Management, [s. L.], v. 1, n. 15, p. 35-48, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583880802700040 [ Links ]

MELO, A. et al. Uma proposta educativa na participação de todos: documento de estratégia para desenvolvimento da educação de adultos. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, 1998. [ Links ]

MONTEIRO, A. et al. (2015). Novos públicos do Ensino Superior: abordagem à aprendizagem de estudantes Maiores de 23 anos. Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia, 49(1). Coimbra, 2015, p. 131-149. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8614_49-1_6 [ Links ]

MOIO, I. Reconhecimento de Competências no Ensino Superior: uma realidade reconhecida ou a reconhecer? Dissertação de Doutoramento (não publicada). Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação, Universidade de Coimbra, 2017. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, A. Política de Educação. In BARROS, A.; MÓNICA, M. F. (coord). Dicionário de história de Portugal. Porto: Livraria Figueirinhas, vol. VII, 1999, p. 591. [ Links ]

PIRES, E. Lei de Bases do Sistema Educativo: apresentação e comentários. Lisboa: Edições ASA, 1987. [ Links ]

PIRES, A. L. O reconhecimento da experiência no Ensino Superior. Um estudo de caso nas universidades públicas portuguesas. Comunicação apresentada no XV Colóquio da AFIRSE: Complexidade: um novo paradigma para investigar e intervir em educação, Lisboa, Portugal, fevereiro de 2007. [ Links ]

PIRES, A. L. Reconhecimento e validação das aprendizagens não formais e informais no ensino superior. Problemas e perspectivas. Revista Medi@ções, 1(2). Setúbal - Portugal, 2010, p. 148-161. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Portaria n.º 854-A/99 de 04 de outubro. Diário da República n.º 232/99 - I Série B. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, 1999. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Assembleia da República. Lei nº3/79 de 10 de janeiro - Eliminação do Analfabetismo. Diário da República. Nº 08 - I Série. Lisboa, 1979, p. 35-36. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Regulamento n.º 43/2007, de 26 de março. Diário da República n.º 60 - 2.ª Série. Universidade de Coimbra: Reitoria, 2007. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Lei n.º 5/73 de 25 de julho. Diário da República n.º 173/73 - I Série. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação Nacional, 1973. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Lei n.º 46/86 de 14 de outubro. Diário da República n.º 237/86 - I Série A. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação e Cultura, 1986. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Lei n.º 115/97 de 19 de setembro. Diário da República n.º 217/97 - I Série A. Lisboa: Assembleia da República, 1997. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Lei n.º 49/05 de 30 de agosto. Diário da República n.º 166/05 - I Série A. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, 2005. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 402/73 de 11 de agosto. Diário da República n.º 188/73 - I Série. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação Nacional, 1973. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 393-B/99 de 02 de outubro. Diário da República n.º 231/99 - I Série - A. Lisboa: Ministério da Educação, 1999. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 64/06 de 21 de março. Diário da República n.º 57/06 - I Série A. Lisboa: Ministério da Ciência, da Tecnologia e do Ensino Superior, 2006. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 74/06 de 24 de março. Diário da República n.º 60/06 - I Série A. Lisboa: Ministério da Ciência, da Tecnologia e do Ensino Superior, 2006. [ Links ]

PORTUGAL. Decreto-Lei n.º 42/05 de 22 de fevereiro. Diário da República n.º 37/05 - I Série A. Lisboa: Ministério da Ciência, Inovação e Ensino Superior, 2005. [ Links ]

SÁ, C.; DIAS D.; TAVARES, O. Tendências recentes no Ensino Superior Português. Livro A3. Agência de Avaliação e Acreditação do Ensino Superior. Lisboa. Publicação Institucional A3, 2013. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. S. Educação de adultos. Educação para o desenvolvimento. Porto: Edições ASA, 1990. [ Links ]

TEODORO, A.; GALEGO, C.; MARQUES, F. Do fim dos eleitos ao Processo de Bolonha: as políticas de educação superior em Portugal (1970-2008). Ensino Em-Revista, 17(2). Uberlândia: EDUFU 2010, p. 657-691. [ Links ]

2Ginzburg (1986/2004) researches on the indicia paradigm; for further information check the book The Cheese and the Worms.

3Article 25 in its no. 1 refers to that “the Minister of Education is responsible for approving, by means of an Ordinance, the regulation of special competitions, which comprises: a) the rules governing the request for enrolment and registration; b) the list of post-high school courses covered by subparagraph c) of no. 1 in article 10, the possible additional conditions that holders of this degrees must meet, namely professional experience, and higher education courses which each one gives access to” and, in its no. 2, that “the Director General of Higher Education is responsible for establishing, by means of an Ordinance, the deadlines for accomplishment of the procedures the present diploma refers to”.

4Access Qualification” is defined as holding a high school course, or a similar one, and the accomplishment of national exams which are entrance examinations in the intended course.

5For Magalhães et al. (2009), the first period is called “more is better”, having been an expansion phase of 20 years (between 1974 and the middle of 1990’s), and in the second period (from 1997/1998 to 2007/2008), when “more is a problem”, a decrease in private higher education was triggered, followed (in 2003/2004) by a decrease of registrations in public higher education.

6In accordance with no. 1 of Decree-Law no. 198/79, from 29th June, “for some years that, under Decree-Law no. 47587 from 10th March 1967, as pedagogical experience within the legal framework of ministerial dispatches, “ad hoc” exams have been carried out to access higher education concerning individuals who are over 25 years old and do not hold the adequate schooling qualification” (p. 1410).

Received: March 30, 2019; Accepted: May 30, 2019

texto em

texto em