Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-164

Artigos

Michalany editions: teaching guidelines for social studies as devices of cultural standards in Brazil (1973)1

1Universidade Federal do Ceará (Brasil). anacortezirffi@ufc.br

2Universidade Regional do Cariri (Brasil). profanaisabelreis@gmail.com

3Universidade Regional do Cariri (Brasil). professordarlan@gmail.com

This article analyzes the strategy of the didactic manual of social studies of the Michalany editions, of 1973, of destitution of History and its assumptions in favor of Social Studies of Moral and Civism, which ended up arguing that the current Civil-military Dictatorship was, in fact, a democratic experience. As well as perceiving the emphasis on the definition of social roles presented in this manual - and other educational documents instituted by the Dictatorship in Brazil with the perspective of a moral and civic education - instead of History and geography, as a strategy to safeguard democratic principles in the population school-age Brazilian, between 1964 and 1985. Douglas Michalany's Integrated Social Studies Course (for elementary school) and Contribution to the development of Moral and Civic Education and Social and Political Organization were used as sources. Brazil in the 1st and 2nd degree curricula.

Keywords: History; Textbook; Civil-military dictatorship

Este artigo analisa a estratégia do manual didático de estudos sociais das edições Michalany, de 1973, de destituição da História e seus pressupostos em favor dos Estudos Sociais de Moral e Civismo, que terminou por argumentar que a Ditatura Civil-militar vigente se tratava, na verdade, de uma experiência democrática. Como também perceber o destaque para a definição de papeis sociais apresentada nesse manual - e outros documentos educacionais instituídos pela Ditadura no Brasil com a perspectiva de uma educação moral e cívica - no lugar de História e Geografia, como estratégia para resguardar os princípios democráticos na população brasileira em idade escolar, entre 1964 e 1985. Como fontes, foram utilizados o Curso de Estudos Sociais Integrados (para o primeiro grau), de Douglas Michalany, e a Contribuição para o desenvolvimento de Educação Moral e Cívica e de Organização Social e Política no Brasil nos currículos de 1° e 2° graus.

Palavras-chave: História; Manual didático; Ditadura civil-militar

Este artículo analiza la estrategia del manual didáctico de estudios sociales de las ediciones Michalany, de 1973, de la destitución de la Historia y sus supuestos a favor de los Estudios Sociales de la Moral y el Civismo, que acabó por argumentar que la actual Dictadura Cívico-militar era, de hecho, una experiencia democrática. Así como percibir el énfasis en la definición de roles sociales que se presenta en este manual - y otros documentos educativos instituidos por la Dictadura en Brasil con la perspectiva de una educación moral y cívica - en lugar de Historia y Geografía, como una estrategia para salvaguardar los principios democráticos en la población. brasileño en edad escolar, entre 1964 y 1985. Se utilizaron como fuentes el Curso Integrado de Estudios Sociales de Douglas Michalany (para la escuela primaria) y Contribución al desarrollo de la Educación Moral y Cívica y la Organización Social y Política. Brasil en los planes de estudio de 1º y 2º grado.

Palabras clave: Historia; Libro de texto; Dictadura cívico-militar

“E quem garante que a História é carroça abandonada numa beira de estrada ou numa nação inglória? A História é um carro alegre, cheio de um povo contente, que atropela indiferente todo aquele que a negue”. In this excerpt from Cancion por la unidade de Latino America, composed by Pablo Milanês and Chico Buarque de Holanda2, some of the attributes that characterize History were highlighted, both as a field of study and as a discipline. Especially with regard to the political implications that are established from the way in which it is dealt with.

It is necessary to keep in mind the place of history and its importance when thinking about political and historical processes such as the one that has been experienced since the Secondary Education Reform Law3, enacted on February 16, 2017, which transformed the curricular composition of this period. of school education and relegated the subject of History to the status of non-mandatory. Changes like this, however, are not new in the process of building education and school curriculum in Brazil. During the period of the Civil-Military Dictatorship (1964 - 1985), one of the State policies for education at the school level was the exclusion of the Subject History from the curriculum in the first grade, being mandatory study only in a grade of High School. From this exclusion, the discipline of Social Studies was instituted in the Elementary School, which incorporated the studies of History and Geography.

More than combining two disciplines, the military apparatus had other pretensions in dealing with education that denoted awareness of the power relations that could result from the change undertaken. The discipline was remodeled so that it had a conciliatory character with the regime, which wanted a professional training of the population to serve the imperatives of the market and production. In the words of Juliana Miranda de Filgueiras, who studied “Moral and Civic Education and its didactic production between 1969 and 1993, “The school was considered one of the great diffusers of the new mentality to be inculcated - the formation of a national spirit” (FILGUEIRAS, 2008, 85). History was destined to the field of marking dates and heroes and combined with a technical education that aimed to reformulate and adapt the entire educational system to the political and ideological objectives of the 1964 coup.

The aspect that interests this article concerns to the education and teaching of History, which had the scope of the discipline and its curriculum manipulated and relegated to the background. The discussion consists in demonstrating that the removal of History from its place in education, as a compulsory subject and a recognized and independent epistemological field, even in a democratic regime, can prove to be a reckless measure. It is necessary to consider, more precisely, that the imposition of a single curriculum for the so-called social studies, in the aforementioned period, was constituted under democratic arguments. In this sense, it is important to understand that the curricular formation, foreseen during the civil-military dictatorship, with emphasis on the definition of social roles within the perspective that prioritized a moral and civic education, marked in the design of the formation of the nation and the Brazilian people, was established with the justification that it moved within democratic principles of society's participation. And also to analyze how this reading was disseminated through textbooks so that visions of society and nation reached school benches; for Benito (2012, p. 43), didactic productions can be examined as the result of pedagogical discourses on school action and as an indicative object of the values on which the management that regulates them is based.

Among the sources that support this reflection are the didactic manual Curso de Estudos Sociais Integrado produced by Edições Michalany4, authored by Douglas Michalany5, Instituto Histórico e Geográfico de São Paulo and Academia Cristã de Letras. As well as the Contribution to the development of Moral and Civic Education and Social and Political Organization in Brazil in the Elementary and High School curricula, published in 1984. Documentation that is justified for having been an instrument for conveying and convincing the ideals of the regime, in which, paradoxically, it presented such imposition as a democratic action.

Dictatorship, History Teaching and the Didactic Manual

During the period of civil-military dictatorship in Brazil, several strategies of organization and social control were developed. The group of civilian-military that ascended to the Presidency of the Republic through the civil-military coup of 1964, pressed by the need to guarantee their permanence in the government of the country, needed, in order to remain in power, the approval of most of the population, as well as the cancellation of possible outbreaks of revolt. The strategy used to obtain popular control had several aspects, one of the most important was the remodeling of education, especially for children and young people, aimed at adapting their behavior to the required parameters.

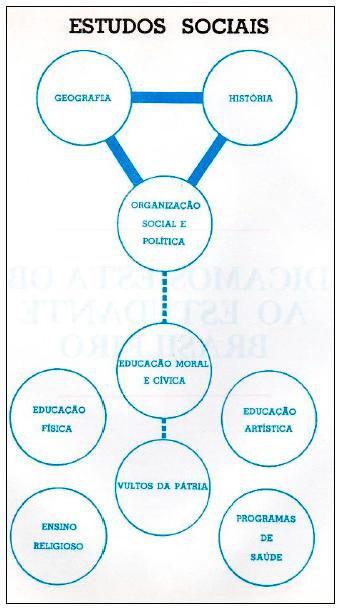

This strategy required the reformulation of the basic education curricula (RIBEIRO JUNIOR, 2015) which united the former primary school to the former gymnasium in a unified 1st grade education, currently elementary, which preceded high school education6. In the meantime, subjects were similarly altered to match new educational aspirations. History, for example, was suppressed from the elementary school, with part of its content included in the Social Studies discipline, which also worked on the themes Social and Political Organization of Brazil, Moral and Civic Education, Physical Education, Art Education, Religious Education, Programs of Health and Figures of the Fatherland.

The product of these changes would also be perceived in the edition of didactic productions, mainly because these volumes occupied, throughout the 20th century, in Brazil, a significant room of these editions. According to Alain Choppin (2004, p. 551), “didactic books corresponded, at the beginning of the 20th century, to two thirds of published books and represented, still in 1996, approximately 61% of national production”. The idea was reinforced for the majority of the population, throughout the 20th century, that didactic textual productions are legitimate sources of historical knowledge. So, it was essential to control what was broadcast in them.

However, the historiographical consensus is that productions that safeguard an intentionality, of being expressly aimed at school education, by the author or editor; the system and the sequence chosen in the exposition of the contents; the textual format, didactic resources and the structuring for the pedagogical work; the use of images articulated to the text; and, mainly, the care in the regulation of the contents according to the provisions of official teaching, as well as the attentive supervision of the State both in the production and in the circulation of these cultural artifacts are constituted in school manuals, going beyond the proposal of the textbook. That is, to be one among other propositions for teaching, without an indoctrination character (Badanelli et al, 2009; Ossenbach, 2010). Thus, according to Cigales and Oliveira (2020, p. 4), “the school manual is an object of the school, but, at the same time, it transcends the pedagogical and didactic interests internal to it”.

In Brazil, the material produced, with regard to Social Studies, underwent modifications in order to be aligned with the new curricular parameters determined by the “Subsidies for Curriculum and Basic Programs of Moral and Civic Education”, of 1970. In the following year, the Federal Council of Education (CFE) also presented Opinion (n° 94) to establish “Curricula and Moral and Civic Education Programs for all levels of education”. From then on, it was noticed an intensification of such determinations for the didactic productions in Brazil, which started to need Homologation by the Ministry of Education and Culture, through the National Commission of Moral and Civism - CNMC7: attesting them with a favorable opinion, or not, in accordance with the terms provided for by decrees No. 869/69, of September 12, 1969, and No. 68,065, of January 14, 1971, and the curriculum programs of the CNMC or CFE.

Among the publishers that modified their productions to adapt them to the provisions of the aforementioned decrees was Edições Michalany, by Douglas Michalany, from the Instituto Histórico e Geográfico de São Paulo and the Academia Cristã de Letras. The 1973 edition, originally Enciclopédia do meu Brasil Collection, was launched as an Integrated Social Studies Course, in two volumes, the object of study of this article8. Here we intend to carry out an analysis of the strategies of social control through the school education of children and young people, carefully observing the notions of formation of the nation and the Brazilian people established there, and the production of textbooks, as well as the intentionality of the production of a didactic manual. Since, as proposed by Benito (2012, p. 44), these should be understood as a holistic representation of the entire teaching culture, a relevant document to reveal some keys to the nebulosity of more traditional school grammar.

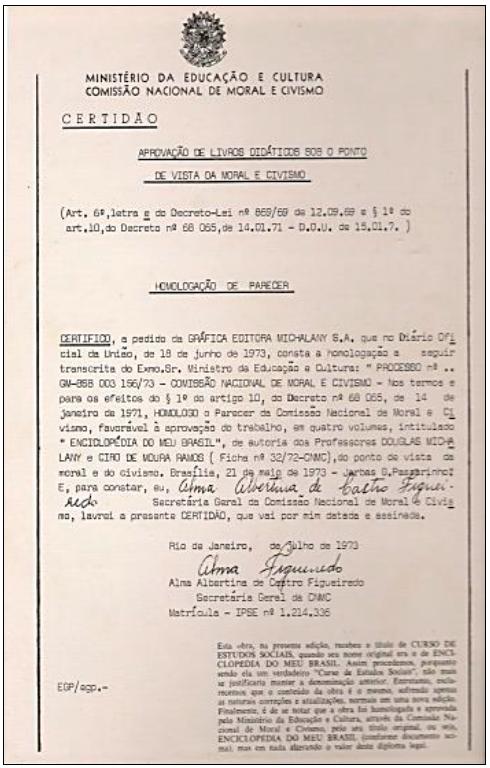

The first aspect to be observed is the record of approval of the work in more than one instance, one of them being the aforementioned National Commission on Morals and Civics - CNMC, linked to the Ministry of Education and Culture, as can be seen in the image below. It is necessary to call attention to the place of the document: fixed on the back of the cover of the manual, constituting the first information brought by the work and that legitimized it as official knowledge9.

Certificate of approval of textbooks from the point of view of morality and civics. SOURCE: PACHECO FILHO, Clóvis; MICHALANY, Douglas; NETO, José de Nicola; RAMOS, Ciro de Moura. Social Studies Course. São Paulo: Editora Michalany S/A, 1982, back cover.

The Integrated Social Studies Course of Edições Michalany received an opinion, on May 21, 1973, "favorable to the approval of the work, in four volumes, entitled ENCYCLOPÉDIA DO MEU BRASIL, authored by professors DOUGLAS MICHALANY and CIRO DE MOURA RAMOS (File no. 32/72 CNMC), from the point of view of morality and civility”. Document signed by Alma Albertina de Castro Figueiredo, Secretary General of the CNMC. As well as the material had to be approved by the Secretary of Education of the State of São Paulo, through a specialized body, Technical Team of the Book and Didactic Material, approved in the process n° 082/75, of April 1, 1975.

The first mentioned approval shows the network of censorship and surveillance instituted during the Brazilian civil-military governments in the field of education. The command claimed by government agencies over the book, and, in this case, the didactic manual allows an appreciation of the behavior model and the cosmovision that would be considered lawful for Brazilian citizens. According to Brigitte Morand (2012, p.70),

the school manual obviously obeys, above all, an institutional demand, whether national, as in France, or originating from a more decentralized structure, as is the case in Germany (RFA). The program thus defines the content of history to be taught and, in this sense, “normalizes” school discourse.

In this way, instilling these devices in children was the way found for a teaching that did not admit resistance or questioning, despite defining itself as democratic. Anyway, beyond this censorship, and, according to Katia Abud, “by not recognizing History and Geography as independent epistemological fields”, and, mainly, placing them at the same level and degree of Moral and Civic Education and Social Organization of Work , in the curriculum, “the public agencies linked to education admitted a pragmatic meaning to the subjects, that of adjusting the individual to society and training the citizen with little awareness (...) their main purpose was to prepare the individual for work” (ABUD, 1999, p. 151).

Thus, the path chosen for this remodeling deprived History of being an epistemological field, and an independent school discipline, and instituted a one-way path to a moral and civic education (what appeared to be a kind of History in a practical sense). Such a strategy was quite evident in the didactic products of that period, such as the organizational chart of studies in the work of Douglas Michalany.

According to the organizational chart shown in the figure, the subjects of History and Geography were combined with the subject of Social and Political Organization, which was divided into six perspectives. In this strategy, much of the content of the disciplines was relegated to oblivion. Defining, in this way, a pragmatic history that only and simply corroborated the intended ideals of nation and citizen; since “school programs are the most powerful instrument of State intervention in education, which means imposing on the school clientele the exercise of citizenship that interests the dominant groups” (ABUD, 2002, p.28).

In this projection of citizenship, which was understood as an ideal, the key points are Moral and Civic Education and the figures of the Fatherland as the great examples to be pursued. In the background, the disciplining of the body and mind was thought of, an activity that would be based on physical and artistic education, religious education and, finally, health programs. Following this path, a model was thus outlined for the Brazilian nation that it was intended to forge. In its editorial, in the preface to the first edition, from 1972, the work of Michalany (1982, p. 10) reinforces this perspective, which he demonstrated in the form of an organizational chart, for the formation of the Brazilian population.

Social Studies aim at the adjustment of man in his environment, placing him in his community and cultivating in his mind the indispensable sense of nationality, with which a responsible citizen will be forged before the Fatherland and Humanity.

Years later, in the preface to the edition studied here, from 1982, the discourse reappeared, as the author's guarantee of being “attended to the evolution of the educational process in its multiple aspects within the current national reality and, at the same time, following the march of a society in constant change and development” (preface, p. 11). Thus, it is “necessary to verify the degree of concreteness of the political-educational discourse, translated into the curriculum and converted into school knowledge, or the degree of adaptation of scientific knowledge-discipline” (MAHAMUD-ANGULO, 2020, p. 10).

Ironically, or not: throughout the work, democracy is used as the argument for accepting the assumptions addressed and disclosed in the manual10. Even in a period marked by a 1969 Constitutional Amendment granted, in which the concentration of power in the Executive stands out, in addition to indirect elections for president.

Without History, the Military Regime was narrated as Democracy.

Democracy, understood as a fundamental concept for the formation of citizens in Michalany's work, is associated with an idea of freedom for the Brazilian people. The first premise presented as the definition of a democratic state stated that “the Brazilian people, by tradition, are democratically formed. Indeed, since the beginning of our political independence, we have always shown the greatest respect for individual rights and guarantees.” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 277).

It is interesting to observe that the notion of freedom advocated by the author in the following pages excluded, from the beginning, the principle of plurality; or even the possibility of a current of thought that was opposed to the dictates of the authoritarian regime. The freedom relegated to the Brazilian citizen was the freedom to obey, which would guarantee him the benefits of citizenship. In the author's ideas, the contradiction was shown: the right to freedom was easily forgotten when any resistance to the current political program was exercised. Thus, continuing the quote transcribed above, the author pointed out that:

However, the current Brazilian Democracy is vigilant and energetic, as it cannot allow subversion and corruption to destroy our institutions. And it could not be otherwise, because the sacred interests of the country are above those of bad Brazilians. (MICHALANY, 1982, 277).

In fact, the exercise of Democracy must avoid attacks on its institutions, as an attitude to guarantee its existence. However, the transcription of Michalany's text is specific: it deals with the current democracy, in Brazil of the civil-military dictatorship - without direct elections for presidents and governors11, with restriction of political parties and without freedom of the press. The categorical discourse already indicated the fragility of its democratic character: it was defined who accepted the administrative dictates and who did not accept them, or who did not completely conform to them, which are the good and the bad Brazilians, respectively. The distinction between good and evil was further reinforced by the understanding of the 'interests of the Fatherland' as sacred, in an attempt to establish a legitimacy along the motto of 'love it or leave it'.

This reference, however, still carried a more disturbing intention between the lines: the idea that, in order to have a 'good' Brazilian, it was necessary to guide his education as an individual and citizen with a rigorous teaching-learning model that altered the school curriculum, with the suppression of the teaching of History in the Elementary School. In this process, History, as a discipline, assumed a skewed concept, being understood only as tradition. Homeland was tradition and tradition was History: “peoples without tradition does not live the life of their homeland, does not feel the past, expects nothing from the future”. In this sense, concepts such as patriotism and citizenship were being articulated to the notion of tradition and, consequently, to the notion of history from the perception that it was through these two currents that love for the Fatherland and the Brazilian People would be instituted: because", knowing the Homeland History, one learns to love the homeland in its Tradition” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 255).

Such an understanding suggests an approach to the typical understanding of a traditional thought of History and Time, as in the so-called Magistra Vitae History, in which the past has a fundamental importance in the perception and understanding of historical time. There is in this thought an idea of an exemplary model, in which tradition, which is confused with History itself, could not be questioned. In this sense, the dogmas imposed by the past through tradition and history were sought in an effort to perpetuate it, to preserve a constancy of human nature. Or, as Reinhart Koselleck defines it for this understanding of history: “History can lead to the relative moral or intellectual improvement of its contemporaries and posterity, but only if and as long as the presuppositions for doing so are basically the same” (KOSELLECK, 2006, 43).

The understanding of an immutable nature and a predictable historical sequence, therefore, is perceived as a guiding principle for the structuring of the units in the manual studied. The notion of the natural evolution of Humanity expressed in the summary is evident, without major references to ruptures, demonstrating an evolution that is immutable and governed by natural laws.

UNITS.

I - The Universe

II - The Earth - Our planet

III - The Human Person - Duties and Rights

IV - The Citizen and the State - Duties and Rights. The Brazilian Citizen

V - The Brazilian State - National Symbols. Monarchy and Republic

VI - Geographic Brazil - Territorial Formation and Physical Aspects

VII - The Brazilian population - Ethnic Formation and Cultural Life

VIII - The Brazil of Today - The Brazilian regions. Integration and Development (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 13).

As can be seen above, the world is expressed as an absolutely compartmentalized system, in which, allegedly, each smaller part added to the others culminate in the whole, the universe. Man is only part of this system. Not by chance, the author stated “that the units were perfectly correlated and intertwined with each other” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 13). With no room for contradiction, there's only room for tradition:

Tradition is immutable, revealing to all deeds, glories, customs, customs, ceremonies, sacrifices, anguish of a people. Tradition identifies a man with his homeland, revealing to him the moral and spiritual value of historical figures, heroes, and brave men. Tradition reveals the national landscape, the common places for everyone, the most distant regions, the historical places where important events happened. Tradition is the twin sister of History, telling the ideals of the past, remembering the deeds, dates, rites, customs, profiles of famous men and women. Like language, history and tradition must be immutable, preserved by all generations, as they constitute the substrate on which nationality is based. Respect for History and Tradition is a civic duty to which every citizen must submit. (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 255).

Since at least the 1970s, the same period of production of Michalany's work, the writing of History underwent crucial changes, especially in the very understanding of this as a school subject. Heir to the questions raised by Luciem Febvre and Marc Bloch, with the publication of the “Annales d'Histoire Économique et Sociale”, in France in 1930, the new perceptions in Brazil began, in spite of the purposes of the civil-military regime, to be disseminated. in postgraduate courses. A problem-history was proposed, with a writing of history against the grain of the political narrative about great men and their deeds, of the history-event from the documents written and understood as official. According to José D'Assunção Barros (2004), in Brazil, these new approaches and research on school subjects, especially related to History, were only established after the end of the dictatorial period, between the 1990s and 2000s, context in which the teaching of History becomes a topic most visited by historians.

Until the end of the dictatorship, however, there was a deliberate gap between the academy and the school12. In this, the ideology of education was focused on economic development completely supervised by the control of National Security.13 For Selva Fonseca, there is, first of all, a political reason, with the intention of controlling and repressing the critical construction of citizens, to eliminate any possibility of resistance to the regime (FONSECA, 1993, p. 25). In this sense, according to the author,

the 1980s are marked by discussions and proposals for changes in the teaching of history. Rescuing the role of History in the curriculum becomes a primary task for several years in which the textbook took on the curricular form, becoming almost an 'exclusive' and 'indispensable' source for the teaching-learning process. (FONSECA, 1993, p.86).

Aligning history with tradition was therefore a part of the political strategy of education in the period of the civil-military regime. However, this positioning went beyond the disciplining of bodies and minds. It built a perception of History that de-characterized it from its own meaning: change and the idea of process. If History was the tradition, it was the immutable of a time that did not fit into the chain of many events lived and still present in the memory of Brazilian citizens. The civil-military period was not questioned because it was still considered present, not yet being tradition or history, but it was distinguished by the design of a nation defined in the memory of deeds, dates, rites, customs, profiles of men. and women considered famous.

History as a support for citizenship

The relationship between History and tradition was, for the creators of education plans in the civil-military regime, the axis on which the idea of nation and citizen would be constituted. To History was not denied its construction process, but it was a knowledge that, once considered produced, became immutable. It was this conceptual approach that gave space to the construction aimed at great names, responsible for outstanding deeds that allowed Brazil to be called a nation. There you have a two-way street: a man who strives for society and the recognition of this name (which would not be that of an ordinary person) as the model to be perpetuated.

The chapters that deal with the formation of the Brazilian nation, written by Michalany and his collaborators, present the Brazilian rulers as protagonists of the nation. In the discussion about the impasse between Portugal, with the Porto Revolution, and Brazil, regarding the independence of the Metropolis, the issue highlighted was not the political-structural change that should have been processed, but the ability of father and son to be genuine rulers for Brazil - the father for colonial Brazil and the son for the Empire of Brazil.

It is clear that Dom João VI, being an intelligent man, understood how things were in Brazil. For this reason, he preferred to see his son on the Brazilian throne, so that the Crown would not fall into the hands of a stranger. And that's what happened: D. Pedro knew how to understand Brazil's problems and made our Independence, becoming our First Emperor (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 349).

The first Emperor knew how to understand the problems that Brazil was going through at that time, as stated in the historical account. Likewise, the definition of citizenship carried by Michalany in the same work corroborated the narrative: love for the Fatherland. “That's the whole meaning of love for the country, because it's ours. Each one loves the country because it is yours. Since it is yours, it is the obligation of every citizen to defend it; defend their homeland against enemies - internal and external - even if it means sacrificing their own lives” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 249). The example of D. Pedro, of devotion to the cause of Brazil, should not only be followed, but copied. However, it was not a matter of understanding History, in its process and as a construction, as a resource for citizenship, but rather thinking of it as a model of citizenship. In this case, as it should be immutable, it would not refer to the process of change of government, but to continuity, which was not foreign to society. For this reason, the plot relies on the characters, namely, the emperors of Brazil.

D. Pedro I had his narrative built on the courage to face the external enemy, Portugal and the struggle for Brazilian recolonization, and on the choice for Brazil. In response to the decree of December 9, 1821, which demanded his return, he declared, a month later, his response: “after reading the manifestos where everyone asked him to stay, the Regent uttered the phrase that would become famous: As it is for the wellfare of all and the general happiness of the nation, I am ready: tell the people that I stay” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 352).

The report not only pointed to the central figure of the Regent, but also to the creation of the nation after D. Pedro. When considering, in the sentence attributed to him, the idea of Brazil as a nation, light was shed, at the same time, on the protagonism required by the regime granted since 1964: the recognition of Brazil as a nation, as it was, and the perception of belonging to it from the subordination to its rulers. It is in this sense that, in the sequence of the report, the author reinforces the ‘dia do fico’ (Day of the stay):

Did you realize the importance of “dia do fico”? He practically represents our Independence; in fact, from the moment that D. Pedro decided to remain in Brazil, he began to disobey orders from Portugal. After that day, Brazil's march towards its political emancipation became faster and faster. (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 352).

A disobedience for the wellfare of Brazil. That was also believed about the implantation of the civil-military Dictatorship. Against internal and external enemies - above all communism - the reins of the nation were taken. In this sense, when proposing such a reading for History, they understood it as the teacher of life. Understanding History only as a tradition safeguarded its condition of exemplary and perpetual knowledge, the ideal subsidy for the legitimation of the civil-military dictatorship regime in Brazil.

On the other hand, the recourse to History should not only reaffirm the dictatorship itself as necessary. The idea of a Brazil taking power - through a coup - could not be highlighted as permanent for the nation, so the reference to abdication - a moment of intense social movements - in the narrative, so that the figure of Pedro II could be highlighted. The biographical part destined for him was entitled “Dom Pedro II, the most beautiful example of the true citizen”, in order not only to demarcate his life as the ideal model of citizenship, but also to remove the passionate behavior of his father.

Unlike his father, who sometimes acted impulsively, D. Pedro II proved to be a calm and thoughtful man, who only made decisions after much reflection. On the other hand, he always tried to hear the opinions of the Council of State, formed by men of wide experience and whose function was to advise the Emperor. Thanks to this prudent attitude, he managed to put an end to the revolutionary upheavals, giving the country 40 years of internal peace (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 245).

The idealized model for Brazilian citizenship was the constitution of a homeland that would be a collective of citizens with marks of belonging to that nation through its History. Thinking about the nation and the best for it was a civic duty of every Brazilian citizen. Such a perspective not only flooded written history at that time, it was the perspective for all teaching. In the document entitled Contribution to the development of Moral and Civic Education and Social and Political Organization in Brazil in Elementary and High School curricula, this perception is evident14: “each man's world is his homeland. And a Fatherland is, in the last analysis, a moral personality. It has a body and a soul. It is a territory, a people, a language (or more than one), a religion (or more than one), a spiritual tradition carried by History” (Contribução..., 1984, p. 97) - quoted by Douglas Michalany (1982, p. 97). This perception is in Michalany not because of his own perception, but because it is part of the civil-military ideology of the governments from 1964 to 1985, which makes a reading of citizenship, homeland and History in a way that corroborates his perception and with democratic tones. This view is also indicated in other documents produced by the civil-military regime, such as the Basic Manual of the Escola Superior de Guerra, in its 1975 edition. Documentation that was produced by various bodies of the control system acting in the field of higher education and points to the same perceptions that permeated the provisions of basic education. As summarized by Jaime Valim Mansan (2017, p. 841), the notions of State and nation used in the manual reinforced the idea of a universal notion for the nation and the State. “Nation was defined as 'an original or immutable social entity', 'society already sedimented by the long cultivation of traditions, customs, language, ideas, vocations, linked to a certain land space and united by the solidarity created by common struggles and vicissitudes'”. And the “State would be ‘the entity of a political nature, instituted in a nation, over which it exercises jurisdictional control, and whose resources it orders to promote the achievement and maintenance of the National Goals”.

The ideal citizen in the democracy of the civil-military dictatorship

Teaching about the Brazilian nation through school didactic literature and reinforcing the patriotic feeling, through the commemorations of dates considered special for the history of Brazil, had a well-defined purpose for the civil-military government: to sculpt the ideal citizen to inhabit and defend this country. However, such a strategy was not restricted to the teaching of subjects that privileged the territory and the great figures that 'built' the nation, since the very existence of the dictatorial regime exposed the fragility of this assertion, especially when it comes to the concepts of citizenship and democracy. With this perception, it was understood that it was necessary to add another indoctrination bias, one that was particularly incisive regarding the interests of the current government. In this process, the teaching of History, already merged with Geography, was associated with that of moral and civic education, and, as the main objective, it was conveniently opted for a discourse that highlighted the 'improvement' of the child's character, of adolescents and young people so that they could be 'good citizens, free and democrats', knowing perfectly well what their duties and rights are towards men and their country.

In an explanation of the progressive method, typical of the didactic production and teaching of a technical nature advocated by the military powers, the author exposed the definition of Education and Moral Education before, finally, defining Moral and Civic Education in a more detailed way. Right at the beginning of the text, Douglas Michalany's (1982, p. 218) care in highlighting the fact that “at a good time the Brazilian Government decided to institute Moral and Civic Education as a compulsory subject at all levels of education, through Decree No. 869, dated September 12, 1969”. It is important to note that the quote was conveniently followed by the transcription of the definition of this 'field of knowledge' in the aforementioned decree, which reverberated and reinforced the ideal citizen model, as it proclaimed:

Moral and Civic Education aims to lead the student to acquire moral and civic habits, through the awareness of principles and the development of the will, for the constant practice of the resulting habits, making them happy and useful to the community (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 218).

What can be seen, on the other hand, is that on the fimbriae of a Moral and Civic Education, there is a perspective of suppression of individualities in favor of the collectivity, or even, of an understanding of life restricted and limited to rights and duties for the population. A perspective that, according to Alexandre Tavares do Nascimento Lira (2010, p. 281), “represented a composition between conservative Catholic thought and the doctrine of national security”. These objectives were pursued through primary education (extended from four to eight years by the Law of Directives and Bases of 1971, art 18), in which the idea of community was highlighted, which was followed by a secondary education (reduced from seven to three years), with a markedly ideological content, whose themes were about “work as a human right and a social duty; the main characteristics of the Brazilian government; the defense of institutions, private property and Christian traditions; citizen's responsibility for national security”.

The teaching of this subject resulted from a proposal by the Escola Superior de Guerra, made within the scope of the Federal Council of Education - CFE, and which in reality was an imposition. The aforementioned proposal was resisted by Anísio Teixeira and Dumerval Trigueiro Mendes, while members of the CFE, but it passed freely after they both left that instance. Dumerval Trigueiro Mendes even exercised his opposition in the production “of normative and doctrinal opinions, communications and seminars of the Council, in conferences and inaugural classes throughout the country”. He also wrote about the subject in articles and essays in the Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos and Revista de Cultura Vozes, as well as publicizing his ideas “in the chairs of History of Economic Thought and Sociology, at UEG (Universidade do Estado da Guanabara) since 1965, and as a professor of Sociological Foundations of Education, after his transfer from the Federal University of Paraíba, in 1968, to the Faculty of Education at UFRJ”. In retaliation for his actions, Dumerval Trigueiro Mendes was informed of his retirement due to Institutional Act n° 5 through a news broadcast on a television program (LIRA, 2010, p. 239).

It is understood, from the experience of Professor Dumerval Trigueiro Mendes, that there were two possibilities for Brazilians in the dictatorial period: to stand against or in favor of the impositions of the civil-military government, especially after the promulgation of the AI5, an act that became known as "the coup within the coup".15 The writings and quotes from the text transcribed from the textbook analyzed here suggest the close involvement of the booklet author himself with the military government, and, in this sense, Douglas Michalany constituted himself an exemplary citizen, unlike Professor Dumerval Trigueiro Mendes. And, therefore, Michalany was able not only to produce the work, but to have it as a reference for teaching throughout Brazil; above all because it followed 'to the letter' all the provisions indicated in the documents intended to govern the teaching produced by the agency responsible for the administration of education in the civil-military apparatus.

This perspective, which supports this author's writing, was evident in the doctrinal part of Opinion No. 94, of February 4, 1971, of the Special Commission for Moral and Civic Education, reported by Reverend D. Luciano Cabral Duarte, in which the project of an ideal citizen had already been indicated, forged through this Education, to contribute to a process of production of the nation in the molds advocated at that juncture. In this opinion, Dom Luciano concluded:

Moral and Civic Education in Brazil, therefore, inspired by the main lines of the National Constitution, will have as its objective the formation of conscientious, solidary, responsible and free citizens, called to participate in the immense effort of integral development that our country is currently undertaking to construction of a democratic society, which makes its own progress, through the human, moral, economic and cultural growth of the people who compose it.

It is important to realize that the proposal to build a democratic society is the justification that runs through the provisions of Moral and Civic Education, as well as throughout Michalany's manual, but his learning was not a free choice and his teaching was diligently organized. The systematization of the contents of Moral and Civic Education in Brazil was launched in 1984 “with the aim of offering one more subsidy to those who, in schools, develop Moral and Civic Education” (Contribuição..., 1984, p. 07). This document contributed to the development of the project of psychosociological formation of the men of the nation, at the same time that it reinforced the dogmatic character of such project. As in the previous documents, the intention to indoctrinate the entire content of the Contribution to the Development of Moral and Civic Education and Social and Political Organization in Brazil in the Elementary and High School curricula is evident.

The compulsory teaching of the subject under discussion in at least two grades of primary education already suggested a systematic teaching method, which, through the repetition of values and principles understood as ideals, gained tones of dogmatization. In more than one moment of the Contribution..., Article 7 of Decree n° 68.065/71 was recalled, which determined that “the subject Moral and Civic Education must integrate the curriculum of at least one of the series of each cycle of High School and a series of Elementary School”16, in an attempt to legitimize this project. Further on, in the Curriculum Disposition of the discipline, it was determined that “Moral and Civic Education, as a discipline, will be taught on a mandatory basis in at least two grades of Elementary School and one of High School”.” (Contribuição..., 1984, p. 33).

However, it is the doctrinal character of this project that is important to highlight. Not as a perspective that insinuated itself between the lines of the didactic manuals approved by the Moral and Civic Education Commission, but as a conscious strategy, based on the composition of a commission itself, on the imposition of teaching and the inclusion of the subject in the production of the didactic text by force of laws and decrees and in the surveillance and reinforcement of this project through the publication of the Contribution..., in 1984. Although it was, above all in the text that composed it, that the need for moral and civic indoctrination was highlighted.

In a specific session, the Contribution... published the “Basic guidelines for the teaching of Moral and Civic Education, in Elementary and High School grade courses. Doctrinal Principles”, which were determined in two points, as transcribed below.

1 - Moral and Civic Education, based on national traditions, aims to;

a) the defense of the democratic principle, through the preservation of the religious spirit, the dignity of the person and the love of freedom with responsibility, under the inspiration of God;

b) the preservation, strengthening and projection of the spiritual and ethical values of nationality;

c) the strengthening of national unity and the feeling of human solidarity;

d) the cult of the Fatherland, its symbols, traditions, institutions and the great figures of its history;

e) the improvement of character, with support in morals, dedication to the community and to the family, seeking to strengthen it as the natural and fundamental nucleus of society, the preparation for marriage and the preservation of the bond that constitutes it.

f) the understanding of the rights and duties of Brazilians and the recognition of the country's socio-political-economic organization;

g) the preparation of citizens for the exercise of civic activities, based on morality, patriotism and constructive action, aiming at the common welfare;

h) the cult of obedience to the Law, fidelity to work and integration into the community.

2 - The philosophical bases discussed in the above item should motivate:

a) the action in the respective disciplines of all the holders of the national teaching profession, public or private, with a view to the formation of the student's conscience;

b) the educational practice of morals and civics in educational establishments, through all school activities, including the development of democratic habits, youth movements, studies of Brazilian problems, civic acts, out-of-school promotions and parental guidance".

In a contradictory discourse, the defense of the dictatorial regime, and its dictates for the Brazilian citizen and people, is formulated from a democratic justification and an obligation for democracy. It becomes the keyword for the definition of dictatorial government. Self-titled democratic, no doubt. It is not by chance that the first purpose of Moral and Civic Education is pointed out as the defense of the democratic principle, but it is followed by a discourse that intertwines the cult of the Fatherland, freedom with responsibility, civic activities, moral foundation, among other aspects that indicate the limitation of that democracy. Also in the Popular Civic Education item of the studied textbook, the reference to democracy as part of the civil-military regime is identified, in a no less caustic passage:

But the great school of civics is the nation, represented by its rulers. Those must teach everyone what democracy is, the value of voting, the responsibility to vote well, the importance of each one for the development of the country, the rights and duties of each citizen. (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 220).

The rights and duties of each citizen were related to moral teaching, thus indicating how the text takes on the character of a manual, teaching teachers and students about the historicity of the discipline and its four areas of scope - Family, school civic education, military and popular -, but also establishes a relationship between this Education and work. In this context, the author of the manual is emphatic:

work is a great social duty, an imperative requirement of society and a vital need for it. No one can live without working, because work is the very raison d'être of life, a duty. The true greatness of man does not consist in seeking pleasures, or celebrity, or honors, but in doing his duty, working (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 220).

In the meantime, behavior that did not fit this work logic was immediately condemned. In the author's words: “no one is more reprehensible than those who do not work, out of self-indulgence or laziness. Thus, they are shirking their obligations and duties, becoming voluntary parasites of a society.” (MICHALANY, 1982, p. 220).

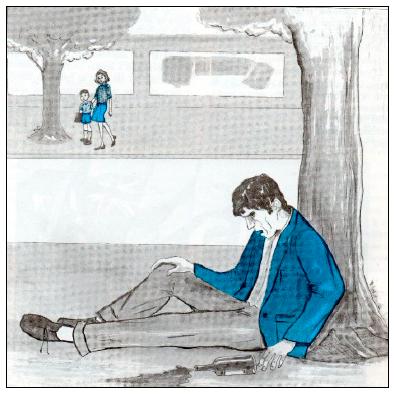

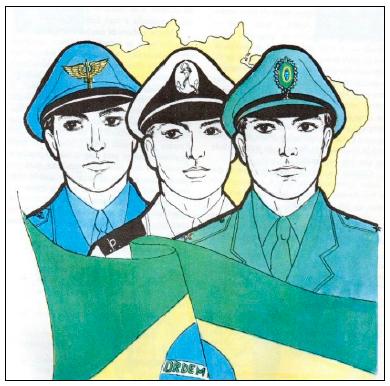

In addition to this more direct and systematic discourse on the behavior and discipline considered ideal for Brazilian citizens, another less systematic, although frequent, discourse was inserted in the pages of the didactic manual, which used images and small assertions that taught so much about nationalist principles and values, as indicated by what was considered unwanted behavior. As can be seen in the images below.

Source: MICHALANY, 1982, p. 149.

“Here is a beautiful example of kindness and charity towards others”.

Source: MICHALANY, 1982, p. 77.

Alcoholism is one of the worst human addictions. It weakens the intelligence and takes away the moral and physical energies of man, leading him to disgrace”.

Source: MICHALANY, 1982, p. 221.

“The Armed Forces play an important role in Civic Education. In the barracks, the idea of the Fatherland is developed, character is formed and, above all, the citizen is given the notion of duty, devotion and sacrifice to the common cause”.

If “a picture speaks a thousand words”, the figures abundantly used in Douglas Michalany's manual played a strategic role in the teaching and learning process.17 The images were used as a tactic to inform a speech more quickly to those who had brief access to the manual, in addition to serving as a reinforcement of the themes that were worked on throughout the work. In all of them there is no indication of any possibility or variety of behaviors and profiles acceptable to Brazilian citizens. Everything is restricted to the exaltation of a behavior considered ideal, of the nationalist, exemplary for obedience to duties and with its maxim in the citizen who is in the armed forces, and another, which is rigidly rejected, associated with vices and dissolute life, and narrated as failure.18 In this sense, there was only one ideal citizen who, by violently repressing variations and differences in the formation of the character and behavior of the Brazilian citizen, ran the risk of being hopelessly conservative.

This understanding, however, implies a disturbing reflection on the extent to which the influence of State actions on the population could reach, since this conservative and authoritarian perspective of Brazil, nation, citizenship - taught to children, adolescents and young people in the school years -, would probably not disappear with the end of the civil-military dictatorship and the holding of direct voting to elect the President of the Republic.

This type of conditioning, on the other hand, explains the fact that many Brazilians left the civil-military dictatorship endowed with a conservative understanding of the world that, hidden from the first reprimands for the crimes committed in that period, could reappear in contexts of relaxation of the same with the Amnesty lawsuits19, for example. Thus, recent calls for the return of dictatorship are based on an indoctrination that an ideal nation can be constituted through a basic citizenship ‘booklet’, like a simple cake recipe. And, even more serious, as if the construction of the democratic period experienced after the end of the dictatorship was his depositary.

Final considerations

All these understandings imply a disturbing reflection of the extent to which the dictatorial period in Brazil was, in fact, understood by the school population as a democratic experience. It is necessary to realize that the actions of the State on the population, through the teaching of History, disguised in Social Studies, contributed to forging a conservative and authoritarian perspective of Brazil, nation and citizenship - taught to children, adolescents and young people in at least three years schoolchildren during the regime. This understanding, apparently, did not disappear only with the end of the military dictatorship and the holding of a direct election to elect the president of the Republic.

Thus, each generation, as pointed out by Escolano Benito (2012, p. 37), is identified, in this sense, by shared manuals, and not only that, but taught from a school definition; that is, by a type of teaching chosen to be propagated. The writings and images of these texts are built as part of the social imaginary of a generation and the narrative identity of the subjects that belong to it. Thus, it is plausible to consider that the extreme right-wing conservative thinking that even calls for the return of the civil-military authoritarian regime in Brazil, in posters, speeches and demonstrations since the 2013 movements, maintains a relationship with the teaching and conception of History (Social Studies) taught during the dictatorship. There are among the population (especially the middle class) those who were educated in the schools of the civil-military dictatorship, with their lessons in Moral and Civic Education, who understand the experience of the military dictatorship as an experience of democracy. And they see in the return to the years of repression the return to building a democracy.

This enticement could cost Brazil dearly, in its fragile democratic experience, if subjects such as History, and others in the Humanities area, continue to be threatened by the advance of technical and professionalizing thinking, projected in the dismantling proposed in the High School Reform Law. Or in the trivialization of the historian's craft by youtubers and bloggers who teach History in videos, podcasts and twitter, even though they don't have the training to do so.

REFERENCES

Badanelli, A., Mahamud, K., Milito, C., Ossenbach, G., & Somoza, M. (2009). Studying history on line, section: school textbooks: Lifelong Learning programme Erasmus. Bruselas, BE: European Commission. In: Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ., 20, e096 2020, 1-7. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Caio Fernandes. Olhares sobre a Capes: ciência e política na ditadura militar (1964-1985). Revista de História, 1, 2 (2009), pp. 99 - 109. [ Links ]

BARROS, José D´Assunção. O campo da História: especialidades e abordagens. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2004. [ Links ]

BENITO, Agustín Escolano. El manual como texto. In: Pro-Posições. v. 23, n. 3 (69) set./dez. 2012, p. 33-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73072012000300003 [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, Circe. Ensino de História: fundamentos e métodos. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

MORAND, Brigitte. Os manuais escolares, mídia de massa e suporte de representações sociais. O exemplo da Guerra Fria nos manuais franceses de História. In: Pro-Posições. v. 23, n. 3 (69) set./dez. 2012, p. 67 - 86. [ Links ]

BUENO, Bruno Bruziguessi. Os Fundamentos da Doutrina de Segurança Nacional e seu Legado na Constituição do Estado Brasileiro Contemporâneo. Revista Sul-Americana de Ciência Política, v. 2, n. 1, 47-64. [ Links ]

CHOPPIN, Alain. História dos livros e das edições didáticas: sobre o estado da arte. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v.30, n.3, p.549-566, set./dez. 2004. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022004000300012 [ Links ]

CIGALES, Marcelo & OLIVEIRA, Amurabi. Aspectos metodológicos na análise de manuais escolares: uma perspectiva relacional. In: Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ., 20, e099 2020, p. 1 - 17. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4025/rbhe.v19.2019.e099 [ Links ]

COMISSÃO NACIONAL DE MORAL E CIVISMO. Contribuição para o desenvolvimento de Educação Moral e Cívica e de Organização Social e Política no Brasil nos currículos de 1° e 2° graus. Rio de Janeiro, MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO E CULTURA, 1984. [ Links ]

PACHECO FILHO, Clóvis; MICHALANY, Douglas; NETO, José de Nicola; RAMOS, Ciro de Moura. Curso de Estudos Sociais. São Paulo: Editora Michalany S/A, 1982. [ Links ]

FILGUEIRAS, J. M. A produção didática de educação moral e cívica: 1970 - 1993. Cadernos de Pesquisa: Pensamento educacional, Curitiba, v. 3, p. 81 - 97, 2008. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Selva Guimarães. Caminhos da História Ensinada. Campinas, SP: Papirus, 1993. [ Links ]

KOSELLECK, Reinhart. Futuro passado: contribuição para a semântica dos tempos modernos. Rio de Janeiro: Contraponto: Ed. PUC-Rio, 2006. [ Links ]

LIRA, Alexandre Tavares do Nascimento. A Legislação de educação no Brasil durante a ditadura militar (1964-1985): um espaço de disputas. Tese (Doutorado) - Universidade Federal Fluminense, Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia, Departamento de História, 2010. [ Links ]

Mahamud, K. Propuesta metodológica multimodal e interdisciplinar en investigación manualística. Rev. Bras. Hist. Educ.,20, e0972020, 1 - 25. [ Links ]

MANSAN, Jaime Valim. A Escola Superior de Guerra e a formação de intelectuais no campo da educação superior no Brasil (1964-1988). Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro: ANPEd; Autores Associados, v.22, n.70, jul.-set. 2017. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/v22n70/1809-449X-rbedu-22-70-00826.pdf. Acesso em: 15 set. 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782017227041 [ Links ]

Ossenbach, G. Manuales escolares y patrimonio histórico-educativo. In: Educatio Siglo XXI, 28(2), 2010, p. 115- 132. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO JUNIOR, Halferd Carlos. Ensino de História e identidade: currículo e livro didático de História de Joaquim Silva. Tese de Doutorado, Campinas, São Paulo, 2015. [ Links ]

ROLLEMBERG, Denise. A ditadura civil-militar em tempo de radicalizações e barbárie. 1968-1974. Francisco Carlos Palomanes Martinho (org.). Democracia e ditadura no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: EdUERJ, 2006. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia M.; STARLING, Heloísa M. Brasil: uma biografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2015. [ Links ]

SILVA, Francisco C.T. da, “Os fascismos”. REIS FILHO, Daniel Aarão (org). Século XX. Vol. II: o tempo das crises. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2000. [ Links ]

2And who can guarantee that History is a cart abandoned on a roadside or in an inglorious nation? History is a happy car, full of a happy people, which indifferently runs over anyone who denies it (Tradução nossa). Composed in 1972 and released in 1973, the song indicated the establishment of ties between Cuba and Argentina (with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara), highlighting military ills that commanded some Latin American countries. This song was recorded by groups such as Clube da Esquina and Raices de America and gained fame in the student movement of the 1970s.

3The law originates from the Provisional Measure of the New High School. As amended in the mixed commission and in the Chamber of Deputies, MPV 746/2016 was presented in the Senate, on November 30, 2016, in the form of the Conversion Law Project (PLV) 34/2016. The rapporteur of the matter, Senator Pedro Chaves (PSC-MS), partially or totally accepted 148 of the 568 amendments presented to the MP.

4The author had the collaboration of Ciro Ramos Pacheco, who, from the 1990s, was professor of History at the Colégio and Curso Objetivo, in São Paulo; José de Nicola Neto, professor of Portuguese since 1968 and author of the Gramática Contemporânea da Língua Portuguesa (Ed. Scipyone, 1999); and Clovis Pacheco Filho, who became a Master in Sociology by the Graduate Program of the Faculty of Education of the State University of São Paulo, defending, in 1994, the Dissertation Dialogue of the Deaf: the difficulties for the construction of sociology and its teaching in the Brazil, having been guided by Prof. Dr. Elza Nadai.

5Born in São Paulo, on August 27, 1921. He graduated in Law and in Social and Political Sciences; Finally, he was a member of the Historical and Geographical Institute of São Paulo, Academia Cristã de Letras, Academia Paulista de História (President for 9 years), and President Emeritus of the same. Available at: http://www.agemcamp.sp.gov.br/cultura/index Official R2 of the National Army. Professor, Writer, Historian, Geographer and Lawyer (OAB 8987 - SP). He has had over 40 published works, in over 70 volumes, as author and co-author. Among them are: “Curso de Estudos Sociais” (3 tomos), “Universo e Humanidade” (3 tomos), “Atlas Histórico, Geográfico e Cívico do Brasil”, “Sermão da Montanha”, “Tradições Cristãs”, “Mural Governantes do Brasil Independente”. He received more than 40 Commendations, Diplomas and Honors from various cultural entities.

7First to compose the CNMC: Gen. Moacir de Araújo Lopes, Prof. Álvaro Moutinho Neiva, Prof. Father Francisco Leme Lopes, Admiral Ary dos Santos Rongel, Prof. Eloywaldo Chagas de Oliveira, Prof. Humberto Grande, Prof. Dr. Guido Ivan de Carvalho, Prof. Hélio de Alcântara Avellar and Prof. Arthur Machado Paupério. This commission was modified over the years, maintaining its character.

8There were also other authors who, according to Juliana Miranda Filgueiras, “searched for different mechanisms to change official prescriptions”. Among them, we can mention Leny Werneck Dornelles, entitled Pátria e Cidadania: EMC, from 1971, and Heloísa Dupas Penteado, entitled O homem, os lugares, os tempos. Moral and Civic Education, 1984. Both studied by Juliana Filgueiras in the text DOIS LIVROS DIDÁTICOS DE EDUCAÇÃO MORAL E CÍVICA DIFERENTES: MECANISMOS DE APROPRIAÇÃO DAS PRESCRIÇÕES OFICIAIS. Available at: http://alb.org.br/arquivo-morto/edições_anteriores/anais16/sem07pdf/sm07 ss13_05.pdf.

9A strategy also emphasized in the research by Mahamud-Angulo (2020, p. 11): “Another methodological implication of the production contexts and the incorporation of their sources points to the qualitative and quantitative representation of the samples of selected manuals. To say, we answer the questions posed at the beginning about what manuals to analyze and how many. Knowledge of the different contextual areas of production ‘allows us to know which authors are relevant, which editorials are prestigious' and to refer to relevant manuals for these criteria or for having received 'awards, positive evaluations (see image 1)22, or having been selected for national and international exhibitions'.

10According to Mahamud-Angulo (2020, p. 10), this is the perspective of the manual, like that of Michalany: understanding the knowledge of the context makes it possible to verify if there is coherence, association between the text and the social, historical, political and scientific. Realizing, for example, how much of the production contexts there are in the texts or what kind of influence - ideological, political, technical, scientific - can be observed.

11Indirect elections for president and governors lasted between 1964 and 1985. During this period, elections for mayors, councilors, state and federal deputy remained direct. Before the civil-military dictatorship, only two presidents were indirectly elected: Marechal Deodoro da Fonseca, in 1891, and Getúlio Vargas, in 1934, during the Provisional Government; both elected by a Constituent Assembly.

12On the process of institutionalization of science in Brazil and its relations with the teaching of history, see (BARBOSA, 2009).

13Doutrina de Segurança Nacional (DSN) National Security Doctrine maintained direct influence on the process of development and social and political formation of Brazilian society. This doctrine gained strength from the institutionalization of its principles on the establishment of relations between the State and Brazilian society, during the civil-military dictatorship (1964-1985), under the cloak of the Cold War, with the strengthening of the economic dependence of the country to the United States. See more in BUENO, 2014.

14Produced by Comissão Nacional de Moral e Civismo (National Commission on Morals and Civics), Rio de Janeiro, in 1984. CNMC: CHAIRWOMAN: Edília Coelho Garcia. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Ruy Vieira da Cunha. ADVISORS: Adolpho João de Paula Couto, Carlos Auto de Andrade, Francisco de Souza Brasil, Gumercindo Rocha Dórea, José Barreto Filho, Magdaleno Girão Barroso e Rodolfo Beker Reifschneider. Available in: http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/download/texto/me002412.pdf.

15Commonly cited expression “to refer to the victory of the military of the so-called hard line, in favor of remaining in power in relation to the soft line, defenders of military intervention only as a resource to guarantee order, with the return to the barracks in the short term”. (ROLLEMBERG, 2006, p. 141-152).

16According to law 5 692/71 "primário" and "ginásio" constituted the old Elementary School (currently Fundamental I and II) and "colegial" corresponded to High School (currently "ensino médio").

17According to Benito (2012, p. 45), “A manual is also a mirror of the society that produces it, to the extent that its contents, language and iconography reflect the values, stereotypes and ideologies that define the established mentality, as it is interpreted by the authors who write it and the filters of the book police that approve it, that is, of the circles and actors that produce and legitimize it. It could even be added, of the expectations of its users, to the extent that these readers are also implicit, since they have been foreseen in the writing of the texts. Texts and images are a faithful representation of the codes of sociability in force in each time and place, epitomized in easy-to-memorize clichés, as befits traditional modes of teaching based on mimesis or reproduction of models”.

18Brigitte Morand (2012, p. 85), in an analysis of the use of images, our didactic manuals point out that they can “help students to acquire a first form of conceptualization, they can have, therefore, apart from their attractiveness, a real didactic interest. But they contain, also, almost always, stereotypes, and it is necessary to study them as such, with the students, which can constitute an excellent means of enriching the history course, mobilizing, then, the interests of the students.

19Amnesty Law is from 1979, in Brazil. Even the work of the Truth Commission was not enough to render it null and void and start a trial period for crimes committed in the Military Dictatorship, as was done in Argentina and Chile. RIBEIRO, Denise Felipe. A anistia brasileira: antecedentes, limites e desdobramentos da ditadura civil-militar à democracia. Thesis (Master in History). Niterói: UFF/ICHF/PPGH, 2012.

Received: May 11, 2022; Accepted: June 10, 2022

texto en

texto en