Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Cadernos de História da Educação

versión On-line ISSN 1982-7806

Cad. Hist. Educ. vol.22 Uberlândia 2023 Epub 07-Ago-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v22-2023-178

Artigos

The monitoring program in higher education, its historical transformations and the possibility of teaching learning1

1Universidade Federal de Viçosa (Brasil). kamilla.oliveira@ufv.br

2Universidade Federal de Viçosa (Brasil). avalente@ufv.br

The aim of this article is to analyze the historical transformations of the monitoring program in the context of higher education. Making use of laws, resolutions and rules, we seek to understand the trajectory of this program, the changes it went through, and whether the monitor function was/ is considered as a teaching learning opportunity. In the development of the research we started by the temporal organization of the documents found at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) exploring the evolution of the monitoring activity and its treatment in the University since 1968, mixing what the law dictated, and how the UFV applied it through its internal resolutions. Along its historical journey, we noticed the using of different terminologies, transformations of its objectives, and its consideration as an activity in which is possible to build necessary knowledges to the teaching profession.

Keywords: Higher education; Monitoring program; Teaching Learning

O objetivo deste artigo é analisar as transformações históricas do programa de monitoria no contexto do ensino superior. Lançando mão de leis, resoluções e regulamentos, buscamos compreender a trajetória desse programa, as mudanças pelas quais passou, e se a função de monitor era/é considerada como uma possibilidade de aprendizagem da docência. No desenvolvimento da pesquisa, iniciamos pela organização temporal dos documentos encontrados na Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), explorando a evolução da atividade de monitoria e o seu tratamento na Universidade, desde 1968, mesclando o que a lei ditava e como a UFV a aplicava por meio de suas resoluções internas. Ao longo de seu percurso histórico, observamos a utilização de diferentes terminologias, as transformações de seus objetivos e a sua consideração como uma atividade em que é possível construir saberes necessários à profissão docente.

Palavras-Chave: Ensino superior; Programa de monitoria; Aprendizagem da docência

El propósito de este artículo es analizar las transformaciones históricas del programa de tutoría en el contexto de la educación superior. Mediante leyes, resoluciones y normativas, buscamos comprender la trayectoria de este programa, los cambios que ha sufrido y si la función de monitor fue/es considerada una posibilidad para el aprendizaje de la docencia. En el desarrollo de la investigación, partimos de la organización temporal de los documentos encontrados en la Universidad Federal de Viçosa (UFV) explorando la evolución de la actividad de tutoría y su tratamiento en la Universidad desde 1968, mezclando lo que dictaba la ley y cómo la UFV lo aplicó, mediante sus acuerdos internos. A lo largo de su trayectoria histórica, notamos el uso de diferentes terminologías, las transformaciones de sus objetivos y su consideración como una actividad en la que es posible construir los conocimientos necesarios para la profesión docente.

Palabras Clave: Enseñanza superior; Programa de tutoría; Aprendizaje de la docencia

Introduction2

The beginning of the monitorship program is based on the monitoral method, which has as its temporal mark the 19th century - a period used to attend a large number of students. This method consisted of "using" students, instructed by a master, in teaching and supervising other students. Although the idea of one student helping another is century-old, the ways, objectives and levels of teaching present distinctions over the years (OLIVEIRA; FERENC, 2020).

It is possible to observe that tutoring is inserted in the context of initial training courses as one of the opportunities of activity to be developed by the student. It can also be considered of great relevance for teaching, when it proposes to assist in the construction of knowledge proper to this profession (HOMEM, 2014); help the student to start in this profession (NUNES, 2007; BEZERRA, 2012) and favor the construction of a learning environment between monitor and students, with less tensions (FLORES, 2018).

The aim of this article is to analyze the historical transformations of the monitorship program. To this end, documentary data were mobilized, since the year 1968, in a research developed in the context of a graduate program in Education, between the years 2018 and 2020. Some guiding questions guided the reflection: what changes are presented by the program, considering past and present time? Was/is the exercise of this activity considered as a teaching learning possibility? To understand such questions, we used laws, resolutions and regulations, analyzing them in the light of authors such as Hypolitto (2000), Marcelo (2009) and Mizukami et al. (2002).

Methodological Procedures

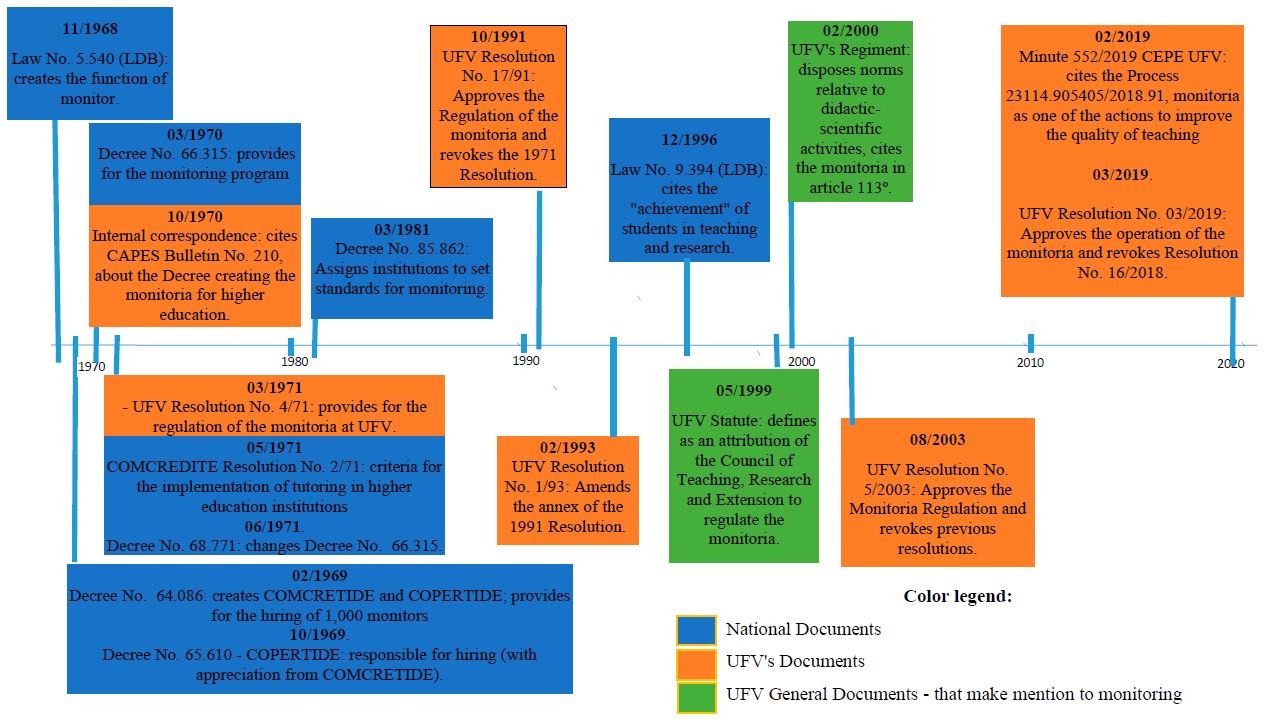

In the development of the research, we began with the temporal organization of the documents found, exploring the evolution of the monitoring activity and its treatment at the University since 1968, mixing what the law dictated and how the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) applied it, through its internal resolutions. Next, we delve into the analysis of the regulations of the monitoring program at the UFV, indicating similarities and differences between the first resolutions and the one currently in force.

To help in the understanding of the transformations of the monitorship, we conducted a survey of various documents, such as laws, national decrees, resolutions and UFV regulations. The analysis was based on guidelines from Sá-Silva, Almeida and Guindani (2009) and Cellard (2008). Inspired by these authors, we understood the documents in question as testimonies of the monitoring activity. We assessed their credibility - judging that they are legal and normative texts - and their representativeness - given that we conducted an exhaustive consultation in the UFV Historical Archive and also on the World Wide Web, in search of documents and, in view of that, we inferred to have a satisfactory corpus in relation to what we proposed in the research, composed of 6 national documents and 8 UFV documents, covering a period of 51 years - from 1968 to 2019.

To structure this article, we opted for a brief temporal presentation of the documents (table 1). After that, we analyzed the regulations of the monitoring program at the UFV and explored, in the national and Ufevian documents, the presence - or not - of the idea of monitoring as a reference for teaching.

In order to deal with monitoring in higher education, we will begin with Law No. 5.540, of November 28, 1968, which set standards for the organization and functioning of higher education, a landmark, since it is this law that provided for the creation of the position of monitor (BRASIL, 1968). In 1969, through Decrees 64.086 and 65.610, the Coordinating Commission for the Full-Time and Exclusive Dedication Regime (COMCRETIDE) and the Permanent Commission for the Full-Time and Exclusive Dedication Regime (COPERTIDE) were created and their functions delegated to them (BRASIL, 1968; 1969a). These commissions were linked to the program for implementation of the full-time regime and exclusive dedication for higher education, which had as one of its objectives the hiring of one thousand monitors. Each university had its own COPERTIDE, and one of its functions was to examine the hiring of monitors, which was later submitted to the COMCRETIDE (BRASIL, 1969a).

The following year, Decree No. 66.315, dated March 13, 1970, was published, which set the full-time faculty program and the available budget, harmonically, to each university's COPERTIDE, which should implement monitoring programs, identifying the subjects, the criteria and the selection rules. In addition, this document established that to act as a monitor, students had to be in the last two years of their course, work 30 hours a week and receive, in 1970, a scholarship of NC$ 300.00 new cruzeiros, provided by the Ministry of Education (BRASIL, 1970). Decree No. 68.771, of June 17, 1971, removed the requirement that the monitor be in the last two years of the course, prohibited the repeating student from exercising monitoring, reduced the time of performance to 12 hours per week and established a scholarship of Cr$250.00 cruzeiros (BRASIL, 1971).

As we pointed out earlier (Chart 1), we noticed, in the 1970s, a frequent production of documents, such as laws and decrees, compared to the following decades. We infer that, after the creation of the position of monitor, it was necessary for leaders to think about the implementation of the program, its criteria, remuneration, selection, and evaluation of monitors. This frequency is decreasing as the decades go by, which may represent the consolidation of the rules concerning monitoring in higher education.

According to Oliven (2002), even though Brazil was going through a period of military government (from 1964 to 1985), Law no. 5.540/1968 brought innovations after several years of twilight-years in which university reform was discussed bureaucratically in closed offices. On the other hand, Durhan (1998) states that in the years prior to this law, there was public debate and movement of students. This law was configured as an effort to "follow the world trend of accelerated expansion of higher education" (DURHAN, 1998, p. 4) and brought as an important modification the idea of a university, at least a public one, dedicated to research. However, the implementation of this model encountered difficulties, especially regarding the number of qualified professors to develop research; in the 1990s, this model was in crisis (DURHAN, 1998).

Thus, the laws implemented during the dictatorship sought to meet the prevailing capitalist model and, despite expanding higher education and graduate studies, placed education at the service of this economic model that imposed on it a technocratic conception, prioritizing productivity, rationalization, and fragmentation of content and focusing on "learning to do" (SILVA, 2016; FALLEIROS, PRONKO, OLIVEIRA, 2010). Thus, we can say that such technician pedagogy guided the educational policy; its echoes can be perceived in the text of the legislation, as we will see in the next section.

Decree No. 85.862, of 1981, assigned higher education institutions the task of establishing conditions for the exercise of the functions of a monitor, following article 41 of Law No. 5.540/1968. The Decree states, in the same way as its two predecessors, that the monitorship did not entail an employment relationship and that the Ministry of Education and Culture would be responsible for its costs (BRASIL, 1981).

We did not find any national documents or UFV resolutions that referred to mentoring between 1981 and 1991. This leads us to infer that, during these ten years, no major legal decisions were made regarding the monitoring program in higher education institutions, and that the activity continued to be developed according to the legislation in force. The documents that governed the activity at the time were, nationally, Decree No. 85.862, of 1981 and Law No. 5.540, of 1968; and, locally (UFV), Resolution No. 3, of 1971.

In 1996, with the publication of the new Law of Directives and Bases for Education, Law nº 9.394, this time contemplating national education in several levels and modalities, it was established that higher education students could "be used in teaching and research tasks by the respective institutions, exercising monitoring functions, according to their performance and their study plan" (BRASIL, 1996, art. 84). However, Souza and Silva (1997, p. 22) judge this article that talks about monitoring as "unnecessary casuistry", that is, a formal and ingenious obedience to the law. The authors suggest that it was "an article with an experimental flavor" and that another law fixing the work regime in universities would be more appropriate.

Besides the flexibilization, the expansion of higher education and the increase in private institutions (BITTAR; OLIVEIRA; MOROSINI, 2008), the LDB/1996 set as one of the ways of evaluating institutions the percentage of teachers with master's and doctoral degrees-which represents a concern with the quality of education, but that can be problematized if we think that the master's and doctoral degrees have been concerned with training researchers and not teachers (PIMENTA; ANASTASIOU, 2005; ALMEIDA, 2012).

In the context of the UFV, its statute (1999) and General Regulation (2000) state that the institution's Council of Teaching, Research and Extension (CEPE) is responsible for establishing qualifications and regulations for the activity of monitoring and the selection of monitors. It is the members of the CEPE who deliberate on the regulations for the UFV's monitoring program, following the current legislation. It was this body that instituted and regulated, through Resolution No. 13/2018, the Permanent Commission for Undergraduate Teaching Monitoring (COPEG), responsible for receiving monitors' performance reports forwarded by advisors, evaluating the program, and having a relevant role in establishing the number of monitors' vacancies.

One of the fruits of COPEG is in the process No. 23114.905405/2019-91, as recorded in Minute No. 552/2019 of CEPE, which presents a set of specific resolutions to reduce failure and evasion in UFV undergraduate programs. Among them is Resolution No. 16/2018, which changes the monitoring program, but which was replaced by Resolution No. 03/2019. Thus, the 2019 resolution configures itself as an attempt by the institution to improve the teaching of its undergraduate courses.

In the years 2003, 2018, and 2019, therefore, the monitoria regulations at UFV were updated. Such documents can help in this process of understanding the history of the monitoria at the institution. With this in mind, in the following section, they will be analyzed, compared, in an effort to assign meanings to their modifications.

Regulations of the monitoring program at UFV: terminologies, monitor's rights and objectives of the activity

The four resolutions about the monitoring program at UFV were published over the course of almost fifty years. Therefore, it is predictable that they will change, since they were thought up in different historical contexts, by commissions composed of various subjects, and signed by various rectors.

Some terminology has been modified, nomenclatures have been replaced by others. The 2019 resolution, for example, replaced the word training (used in previous resolutions) with capacitation, a right that only became explicit in the 1991 resolution. The inclusion of the term training in the 1991 resolution as one of the monitor's rights may reflect the genesis of concern about the monitor's preparation to perform such a role. However, this term reflects a specific paradigm: technical rationality. According to Diniz-Pereira (2006, 2013, 2014), this model based on technical instrumentalization and target of research, from the 1970s, advocated that the teacher would be an applicator of scientific knowledge, learned in their training, in the classroom, in search of efficiency. Based on technical rationality3, these teachers, or future teachers, should be trained.

The influence of the paradigm of technical rationality in educational thinking can also be related to pro-capitalist interests during the Military Dictatorship (1964-1985). According to Lira (2010), during the dictatorial period, Brazilian education, legislation, and politics were taken over by a technologist pedagogy, which aimed at a mechanized, objectified, and rational process. Despite the expansion of higher education, the technician policy inserted into universities sought only to "form a labor force for the market, through a pedagogical training that affected both students and educators (LIRA, 2010, p. 336). The use of the term "training" can be one of the echoes of this technicality of the educational legislation in this period, in which, as mere executors and reproducers, the educator had his work controlled and his knowledge and initiative private.

Given the above, even though the term "training" appears in the 1991 resolution of the UFV Monitor Program, as Correia (2013) explains to us, the educational reforms of the 1990s continued favorable to the capitalist and neoliberal agenda. Thiengo (2018) adds that technologist-or neotechnicist4-pedagogy and technical rationality are present today insofar as education is based on productivity, accountability, acriticism, control, and valorization of technique.

Hypolitto (2000) also helps us to understand the use of these different terminologies in the context of mentoring5. This author presents, semantically, the terms: "recycling," "training, improvement," "update," and "capacitation. For her, the term "recycling" refers to quick and decontextualized courses, being more adequate to objects, and, although it appeared in the 1980s, it is not used in any of the resolutions. For Garcia (1999 apud Hobold, 2018), the term represents something more punctual, focusing on a specific content and/or discipline; "recycling"6 is one aspect of teacher improvement.

In turn, the term "improvement" means to make something complete, perfect, something impossible. The word update, on the other hand, means to make something current, through courses dealing with techniques and methods, for example (HYPOLITTO, 2000). The term "train" refers to repetition, to the idea of making others able to, for example, develop a muscular activity. As Imbernón (2016)7(6) points out, the training-based model was seen as standardized and theoretical, not valuing practice and focusing on developing skills that would lead to expected results. In turn, the term "training" means actions that seek to promote qualification, not only technical but also of change in practice (FUSARI, 1988; HYPOLITTO, 2000).

We can also rely on legal references in the field of education to understand the change from the term "training" to "capacitation" in the UFV's monitoring resolutions. For example, Law 9.394/1996, for example, uses the term "capacitation" when referring to teacher training, although it uses the term "training" when dealing, in its transitory provisions, with the admission of teachers "qualified in higher education or trained through in-service training" (BRASIL, 1996, Art. 87, § 4º).

The resolutions on monitoring leave implicit when this training of the monitor takes place, who offers it, how it is organized, and what content it addresses. If it happens while the monitors are already working, we are faced with the possibility of another term, whose use may be relevant in this context, provided it is adapted. This is the term "professional development," which refers to evolution and continuity, presupposing "contextual, organizational, and change-oriented character" (GARCIA, 1999, p. 137).

Thus, professional development will involve someone learning knowledge, actions, and skills linked to a real and concrete context, thus fitting the idea of evolution and continuity of the individual and collective process of teacher training (GARCIA, 1999; MARCELO, 2009).

Therefore, we infer that the term "capacitation," used in the 2019 resolution, is adequate for the current context and expresses the idea of technical and critical qualification. However, making aspects of this capacity building explicit in the resolutions could help our reflection on other terms, such as professional development.

Another relevant substitution in terms of nomenclature, which we can observe in the 2019 resolution, is the exchange of the word pupil for the word student, although in some articles of the document the word student is still used. Contrary to what common sense suggests, the word "student" does not mean one without light. This word has its origin in the Latin alumnu, which means "breast child, infant, boy, pupil, disciple" (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009, p. 106). The meaning of the word refers to a person who receives instruction, education, who has little knowledge about a certain topic (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009; FERREIRA, 1986).

The term student, on the other hand, refers to a person who regularly attends some course through which he or she acquires skills and knowledge. Its etymology reveals that it is the junction of the term study with the suffix "-nte" (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009), i.e., the agent of the study process, who practices the study action (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009; PORTAL SÃO FRANCISCO, s./d.).

However, to understand the use of such terminology, we need to go beyond its etymology. Chervel (1990), when reflecting on the history of school subjects, brings relevant considerations about the use of the term student. For the author in question, in primary and secondary education, it was necessary not only to teach students the contents of the subjects but also to transmit culture to them. However, in higher education, whose intention would be the direct transmission of knowledge without the need to adapt this content to the age group of the subject, "what is asked of the student is to "study" this subject in order to master and assimilate it: he is a "student"" (CHERVEL, 1990, p. 185).

Besides the terms mentioned above, another term that appears in the resolutions is the term discente, which refers to the act of studying, knowing, learning, and being the antonym of docente (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009; FERREIRA, 1986)-a term also widely used in the academic context (HOUAISS, VILLAR, FRANCO, 2009).

As we could observe, the different terminologies used to represent those subjects who attend higher education refer to learning and building knowledge. Although they can be considered synonyms, the terms found in the resolutions about monitoring students refer to different meanings, evoking, or not, the passivity of the subject enrolled in a higher education course.

Besides the transformations in terminologies, another aspect that we noticed in the resolutions of the UFV monitoring program concerns the changes in the rights of the monitor, such as: proof of performance in monitoring; right to a scholarship (except for volunteer monitors, added in the 2019 resolution); time for planning and exercise of the monitoring; in addition to training to perform the monitoring. All these rights have been guaranteed since the 1991 resolution. The 1971 resolution, on the other hand, spells out only two of these rights: receipt of a scholarship and a certificate of exercise, the latter being pointed out as a prerequisite for later entry into a teaching career in higher education.

Another important transformation in the UFV's monitoring regulations is, without a doubt, in regard to the objectives of the monitoring program. These are explained in the resolution of the UFV monitoring program for the first time in the 1991 resolution8(7) and remained the same in the 2003 resolution. However, such objectives were considerably modified in the 2019 resolution, as we can see in table 2, below.

Table 2 The objective of the UFV monitoring program, according to resolutions from 2003 and 2019

| Goals in Resolution No. 5/2003 | Goals in Resolution 3/2019 |

|---|---|

| I - to improve the students' learning level by promoting closer contact between students and teachers and with the content of the subjects involved; II - to provide the monitor with the opportunity for didactic and scientific enrichment, enabling him/her to better develop teaching, research, and extension activities; III - providing the monitor with the opportunity for scientific and cultural development, allowing him/her to broaden coexistence with people of diversified interests; IV - making the monitoring an integral part of the educational process of the students who exercise it. |

I - raising the level of undergraduate student learning; II - reduce failure rates in disciplines and dropout rates from the course, the institution and the higher education system; III - providing the monitor with didactic-scientific training and qualifying him/her for teaching. |

Source: Resolutions on the UFV monitoring program (UFV, 2003; 2019).

It can be noted that some terms were modified; for example, the word improve was replaced by raise and the term students was replaced by students-as already pointed out earlier in this article. Some terms were deleted, such as the promotion of "closer contact between students and teachers and with the content of the subject(s) involved" (UFV, 2013, art. 1), as well as the opportunity for cultural development and interaction with people of different interests. Other terms were added: the possibility of reducing failure and dropout rates through monitoring and the training of the monitor for teaching.

According to CEPE Minute No. 552/2019, the monitoria program is part of one of the actions to curb failure and evasion in UFV undergraduate courses, which is explicitly stated as one of its objectives in the 2019 resolution. The concern of the institution's higher administration with improvements in undergraduate teaching, with the help of the monitorship, is currently explicit in the 2019 resolution. As for the training for teaching through monitoring, we will deal with the aspects directly related to this subject in the next section of this article.

According to a comparative study among the objectives of the monitorship, conducted by Oliveira and Ferenc (2020), using regulations of the monitorship programs in 10 institutions in Minas Gerais, among them the UFV, it is noted that the initiation to teaching and the contact and cooperation between professors and students have been relevant aspects and contemplated in these objectives. Other aspects appear in the objectives, among them: support for academic activities; seeking improvement in learning; enrichment of the monitor, whether in teaching, research and extension, in cultural, technical, and scientific aspects or in attitudes of responsibility and leadership; and cooperation among students (OLIVEIRA; FERENC, 2020).

In this context, the UFV is aligned with other universities, taking into account the importance of the initiation to teaching-from the perspective of the monitor-and the improvement of learning-from the perspective of those who attend the monitoring.

The learning of teaching in the documents that govern monitoring in higher education

Learning to be a teacher has been the subject of research since the 1980s (MIZUKAMI et al., 2002). Learning to be a teacher involves content, methodologies, skills and can happen through examples of other teachers, through readings, theories, or experience, through reflection (FERENC, 2005; SARAIVA, 2005; NEVES, 2014). In this sense, we analyzed if the documents that fixed or set rules and regulations about the monitoring made explicit or explicit a relationship between the exercise of this activity and the possibility of learning to be a teacher.

Taking Law no. 5.540, of November 1968, as a starting point, which established norms for the organization and functioning of Brazilian higher education, we observed that the document stated that undergraduate students who demonstrated ability could exercise the function of monitor and that such exercise would be considered a title to enter the teaching career. Resolution no. 4/71 of the UFV's Coordination of Teaching, Research, and Extension, which regulated the institution's monitoring activities, also stated that the exercise of the monitoring function would be considered a title for entry into teaching (or other professional activities), which may demonstrate the appreciation of monitoring as a relevant experience for the future exercise of teaching.

One of the indications that tutoring is related to the teaching career may be noticed by the fact that, when examining the functions of COPERTIDE, which included establishing rules for the probationary period, inspecting teachers' activities and evaluating them, and examining the convenience of extending or suspending teachers' exclusive dedication, it was also found to hire student monitors (BRASIL, 1969a, 1969b). Thus, the departments would be able to assess the workload of professors and, based on this, request monitors. By establishing that a Commission on Teaching Careers had decisions involving monitoring, a close relationship between these activities is admitted.

Decree No. 66.315 of 1970 established that monitors were those who demonstrated knowledge of the subject and the ability to assist the teacher in "classes, research and other technical and teaching activities" (BRASIL, 1970, Artº 1º). It stated that the monitoring programs should take place in the priority areas of health, technology, and the training of teachers to work at the high school level. Therefore, we can infer that the monitorship was related to teaching in higher education since it was established that the monitor should help in the university's teaching activities and establish a connection with the high school level.

Moreover, the idea of monitoring as "awakening a taste for the teaching career and for research" appears explicitly in resolution No. 2 of 1971 (COMCRETIDE, 1971, item 1.1), which sets criteria for implementation of the program in higher education institutions. Currently, in the context of the UFV, the regulation of the monitorship explicitly states as an objective, in relation to the monitors, "to train them for teaching" (UFV, 2019, Art. 1).

In the previous regulation, from 1991, one of the objectives was to enable the monitor to develop teaching, research, and extension activities (UFV, 1991). We thus observe that this document did not yet refer to an explicit connection between teaching and monitoring, which was modified in its successor, the 2019 resolution, in which it deliberately chooses to expose the word "teaching".

Although, currently, the objectives of the monitoring activity at the UFV focus more on the perspective of the student who attends the monitoring-improvement of learning, reduction of evasion and failure-the perspective of the one who carries out the activity is taken into consideration, that is, the advantages for the monitor, in the form of training to exercise teaching. We perceive a two-way street in the paths of the monitorship, this being an activity that supports undergraduate teaching and a formative possibility for the monitor.

It can be seen, therefore, that some documents dealing with monitoring have considered it since the creation of the function of monitoring, an activity that can make teaching and learning possible. But what have the scholars, for whom this theme is the object of study, made of scientific findings about its relationship with teaching?

According to a study conducted by Homem (2014)9, the student's activity of playing the role of monitor can generate "several learning possibilities for their training as students in general, and as future teachers in particular" (Homem, 2014, p. 137). The subjects who participated in the research by Homem (2014) highlighted the knowledge needed by the teacher, which was built during their work as monitors, such as expanding knowledge about the subject, assisting in the preparation of teaching activities, planning, and seeking strategies to resolve doubts. In addition, tutoring also involves interactions among students and between the teacher and the student-an aspect also present in the teaching life (HOMEM, 2014).

Medeiros (2018)10 reinforces the contributions of monitoring by stating that it can contribute to the construction of knowledge that involves planning, execution, and evaluation; deepening in the content of the discipline; socialization of knowledge in events; as well as the experience with other students and the supervising teacher. In addition to teaching in higher education, monitoring can contribute to teacher training at other levels of education (MEDEIROS, 2018).

However, even if the monitoring is seen by the institutions as an activity capable of promoting the identification with the teaching career, some of them have reproduced questionable ideas, as is the case pointed out by Oliveira and Ferenc (2020), of two institutional sites, which cite the awakening to the "vocation" for teaching and the opportunity to work as a teacher.

As the authors point out, the understanding of teaching as a vocation dates back to the sixteenth century, when no training was required to exercise the activity (NÓVOA, 1992; TEDESCO; FANFANI, 2004; TARDIF, 2013). As for the idea of monitoring as work, the authors infer that it would be more appropriate to think of it as an opportunity to learn to be a teacher, since teaching started to be seen as a craft for which specific training is required, still in the nineteenth century (NÓVOA, 1992; TARDIF, 2013; OLIVEIRA; FERENC, 2020).

Moreover, even if the regiments signal the possibility of teaching and learning, the monitoring program goes far beyond what is established in the documents. Neves and Ferenc (2016), when investigating students participating in the Initiation to Teaching Program (PIBID), point to the divergences that may occur between propositions contained in a project and actions carried out in practice. These modifications are expected due to temporal, contextual, and personal influences. In this sense, the authors highlight aspects that can impact the implementation of a project, such as the unpredictability of daily practice; demands imposed on students on a daily basis; the need for more guidance from those involved in the process; the relational nature of the activities; and the dependence of students on the authorities to which they submit themselves. They found in their research that teaching learning can happen, even if there are modifications between what is set in the project and the actions that are actually implemented (NEVES & FERENC, 2016).

Final considerations

The documentary research allowed us to understand the trajectory of the monitoring program, from its origins, with the monitoral method, to how we know it today in higher education institutions. We noticed that there were, along the historical path, some transformations, similarities and differences, as is the case of the level of schooling attended to.

As far as the regulations of the UFV monitoring program are concerned, we noticed the modification of certain terminology, such as the replacement of the term training by capacity building and student by student, which may mean the influence of certain paradigms of teacher training as well as of political and economic models, such as the capitalist ideals that have appeared since the Military Dictatorship and that permeate education to this day. However, the substitution of terms over the decades may also mean an effort by those who think these documents in the valorization of a more active and critical posture of the subjects involved in monitoring.

As for the objectives of the activity, we saw that the monitorship method was created to serve a large number of students, aid in their progress and the work of the teachers. However, monitoring in higher education has regimentally served different purposes, among them the reduction of dropout and failure rates; aid in the relationship between students and teacher and student; and the learning of teaching.

Through the documentary and bibliographic research carried out for this work, it was possible to observe that monitoring in higher education has been, by law, considered an activity that enables learning to teach. Authors who have dedicated themselves to the study of monitoring, especially those mentioned in this work-especially those presented in the previous section-corroborate this possibility by stating that monitoring, in practice, has helped student monitors to build the knowledge necessary for the teaching profession.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, M. I. Formação do professor do ensino superior: desafios e políticas institucionais. São Paulo: Cortez, 2012. [ Links ]

BITTAR, M.; OLIVEIRA, J. F. de; MOROSINI, M. (Org.). Educação superior no Brasil: 10 anos pós-LDB. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2008. [ Links ]

BEZERRA, J. K. A. Monitoria de iniciação à docência no contexto da Universidade Federal do Ceará. Dissertação (Profissionalizante em Políticas Públicas e Gestão da Educação Superior) - Universidade Federal do Ceará - Fortaleza, Ceará, 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 5.540, de 28 de novembro de 1968. Fixa normas de organização e funcionamento do ensino superior e sua articulação com a escola média, e dá outras providências. Brasília, 1968. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 65.610, de 23 de outubro de 1969. Dispõe sobre a constituição e funcionamento das Comissões Permanentes do Regime de Tempo Integral e Dedicação Exclusiva e dá outras providências. Brasília, 1969a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 64.086, de 11 de fevereiro de 1969. Dispõe sobre o regime de trabalho e retribuição do magistério superior federal, aprova programa de incentivo à implantação do regime de tempo integral e dedicação exclusiva, e dá outras providências. Brasília, 1969b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 66.315, de 13 de março de 1970. Dispõe sobre o programa de participação do estudante em trabalhos de magistério e em outras atividades dos estabelecimentos de ensino superior federal. Brasília, 1970. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 68.771, de 17 de junho de 1971. Altera o Decreto nº 66.315, de 13 de março de 1970. Brasília, 1971. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 85.862, de 31 de março de 1981. Atribui competências às instituições de ensino superior para fixar as condições necessárias ao exercício das funções de monitoria e dá outras providências. Brasília, 1981. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, 1996. [ Links ]

CELLARD, A. Análise documental. In: POUPART, J. et al. A pesquisa qualitativa: enfoques epistemológicos e metodológicos. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2008. p. 295-316. [ Links ]

CHERVEL, A. História das disciplinas escolares: reflexões sobre um campo de pesquisa. Teoria & Educação, n. 2, p. 177-229, 1990. [ Links ]

COMCRETIDE. Resolução nº 02/71. Critérios para a implantação do plano de monitoria nos estabelecimentos federais de ensino superior. Ministério da Educação, Brasília, 1971. [ Links ]

CORREIA, W. F. O que é conservadorismo em educação? Conjectura: Filos. Educ., Caxias do Sul, v. 18, n. 2, p. 78-90, mai./ago. 2013. [ Links ]

DINIZ-PEREIRA, J. E. Formação de professores: pesquisas, representações e poder. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2006. [ Links ]

DINIZ-PEREIRA, J. E. A construção do campo da pesquisa sobre formação de professores. Revista da FAEEBA - Educação e Contemporaneidade, v. 22, n. 40, p. 145-154, jul./dez. 2013. [ Links ]

DINIZ-PEREIRA, J. E. Da racionalidade técnica à racionalidade crítica: formação docente e transformação social. Perspectiva em Diálogo: Revista de Educação e Sociedade, Naviraí, v.01, n.01, p. 34-42, jan./jun. 2014. [ Links ]

DURHAN, E. R. Uma política para o ensino superior brasileiro: diagnóstico e proposta. São Paulo: Núcleo de Pesquisas sobre Ensino Superior Universidade de São Paulo. 1998. Disponível em: http://nupps.usp.br/downloads/docs/dt9801.pdf. Acesso em: 11 out. 2019. [ Links ]

FALLEIROS, I; PRONKO, M. A.; OLIVEIRA, M. T. C. Fundamentos históricos da formação/atuação dos intelectuais da nova pedagogia da hegemonia. In: NEVES, L. M. W et al. (Org.) Direita para o social e esquerda para o capital: intelectuais da nova pedagogia da hegemonia no Brasil. São Paulo: Xamã, 2010. p. 39-95. [ Links ]

FERENC, A. V. F. Como o professor universitário aprende a ensinar? Um estudo na perspectiva da socialização profissional. 2005. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-32832005000300020 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, A. B. de H. Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1986. [ Links ]

FLORES, J. B. Monitoria de Cálculo e Processo de Aprendizagem: perspectivas à luz da sócio-interatividade e da teoria dos três mundos da matemática. Tese (Doutorado em Educação em Ciências e Matemática) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, 2018. [ Links ]

FUSARI, J C. Tendências históricas do treinamento em educação: a direção e a questão pedagógica, 1988. Disponível em: http://smeduquedecaxias.rj.gov.br/nead/Biblioteca/Forma %C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Continuada/Artigos%20Diversos/tend%C3%AAncias%20hist%C3%B3ricas%20do%20treinamento%20em%20educa%C3%A7%C3%A3o.pdf. Acesso em: 04 out. 2019. [ Links ]

GARCIA, C. M. Estrutura conceptual da formação de professores. formação de professores: para uma mudança educativa. Porto, Portugal: Porto Editora, 1999. [ Links ]

HOBOLD, M. S. Desenvolvimento profissional dos professores: aspectos conceituais e práticos. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v.13, n.2, p. 425-442, mai./ago. 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.13i2.0010 [ Links ]

HOMEM, C. S. Contribuições do programa de monitoria da UFMT para a formação inicial à docência no ensino superior. 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, 2014. [ Links ]

HOUAISS, A.; VILLAR, M. de S.; FRANCO, F. M.de M. Dicionário Houaiss da língua portuguesa. Instituto Houaiss de Lexicografia e Banco de Dados da Língua Portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 2009. [ Links ]

HYPOLITTO, D. Formação continuada: análise de termos. Integração, Ensino, Pesquisa e Extensão, n. 21, p. 101-103, 2000. [ Links ]

IMBERNÓN, F. Qualidade do ensino e formação do professorado: uma mudança necessária. São Paulo: Cortez, 2016. [ Links ]

LIRA, A. T. do N. A Legislação de educação no Brasil durante a ditadura militar (1964-1985): um espaço de disputas. Tese (Doutorado em História Social). Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 2010. [ Links ]

MARCELO, C. Desenvolvimento Profissional Docente: passado e futuro. Sísifo: Revista de Ciências da Educação, n. 8, jan./abr. 2009. [ Links ]

MEDEIROS, L G. C. Saberes da monitoria: uma análise a partir do curso de Pedagogia da Universidade Federal da Paraíba. 2018. Dissertação (Mestrado em Políticas Públicas, Gestão e Avaliação da Educação Superior) - Universidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, 2018. [ Links ]

MIZUKAMI, M. G. N. et al. Escola e aprendizagem da docência: processos de investigação e formação. São Carlos: EdUFSCar, 2002. [ Links ]

NEVES, E. R. Aprendendo a docência: processos de formação de licenciandos em Pedagogia integrantes do Programa Institucional de Bolsa de Iniciação à Docência (PIBID). 2014. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, 2014. [ Links ]

NEVES, E. R.; FERENC, A. V. F. O PIBID Pedagogia e a aprendizagem da docência: proposições e ações efetivas. RIAEE: Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, v. 11, n. 4, 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21723/riaee.v11.n4.7816 [ Links ]

NÓVOA, A. (Org.). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa: Instituto de Inovação Educacional e autores, 1992. [ Links ]

NUNES, J. B. C. Monitoria acadêmica: espaço de formação. In: SANTOS, M. M.; LINS, N. M. (Org.). A monitoria como espaço de iniciação à docência: possibilidades e trajetórias. Coleção pedagógica, n.9, Natal: EDUFRN, 2007. p. 45-57. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, K. M. de; FERENC, A. V. F. Monitoria: da escola às Universidades, passado e presente. In: X COPEHE - CONGRESSO DE PESQUISA E ENSINO DE HISTÓRIA DA EDUCAÇÃO EM MINAS GERAIS, Diamantina, 2020. Anais [...] Diamantina: UFVJM, 2020. [ Links ]

OLIVEN, A. C. Histórico da educação superior no Brasil. In: SOARES, M. S. A. (Org.). A educação superior no Brasil. Brasília: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, 2002. p. 31-42. [ Links ]

PÉREZ GÓMEZ, A. O pensamento prático do professor: a formação do professor como profissional reflexivo. In: NÓVOA, A. (Org.). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa, Portugal: Instituto de Inovação Educacional e autores, 1992. p. 93-114. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, S. G.; ANASTASIOU, L. G. C. Docência no ensino superior. São Paulo: Cortez, 2005. [ Links ]

PORTAL SÃO FRANCISCO. Sufixo - o que é. s./d. Disponível em: https://www.portalsaofrancisco.com.br/portugues/sufixo. Acesso em: 15 out. 2019. [ Links ]

SARAIVA, A.C.L.C. Representações sociais da aprendizagem docente de professores universitários em suas trajetórias de formação. 2005. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação de Minas Gerais, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2005. [ Links ]

SÁ-SILVA, J. R; ALMEIDA, C. D; GUINDANI, J. F. Pesquisa Documental: pistas teóricas e metodológicas. Revista Brasileira de História & Ciências Sociais, ano 1, n. 1, jul. 2009. [ Links ]

SCHÖN, D. A. Formar professores como profissionais reflexivos. In: NÓVOA, A. (org). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa: Instituto de Inovação Educacional e autores, 1992. p. 77-91. [ Links ]

SILVA. A. V. M. A pedagogia tecnicista e a organização do sistema de ensino brasileiro. Revista HISTEDBR On-line, Campinas, n.70, p.197-209, dez. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20396/rho.v16i70.8644737 [ Links ]

SOUZA, P. N. P; SILVA, E. B. Como entender e aplicar a nova LDB. São Paulo: Pioneira, 1997. [ Links ]

TARDIF, M. A profissionalização do ensino passados trinta anos: dois passos para a frente, três para trás. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v.34, n.123, abr./jun. 2013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302013000200013 [ Links ]

TEDESCO, J. Ca.; FANFANI, E. T. Nuevos maestros para nuevos estudiantes. In: PEARL, M. et al. Maestros em América Latina: nuevas perspectivas sobre su formación y Desempeño, Santiago de Chile: Preal, 2004. p. 67-96. [ Links ]

THIENGO, L. C. A pedagogia tecnicista e a educação superior brasileira. Cadernos UniFOA. Volta Redonda, n.38, p.59-68, dez.2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47385/cadunifoa.v13.n38.2612 [ Links ]

UFV, ESTATUTO DA UFV. Estabelece o Estatuto da Universidade Federal de Viçosa, UFV, 1999. [ Links ]

UFV. REGIMENTO GERAL DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE VIÇOSA. Normatiza atividades didático-científicas e administrativas comuns aos órgãos integrantes da Universidade Federal de Viçosa e estabelece métodos de ação concernentes aos vários aspectos da vida universitária, explicitando princípios e disposições estatutárias e fixando padrões normativos aos quais deverá ajustar-se a elaboração de regimentos específicos, UFV, 2000. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 12/2008. Estabelece novos valores para as bolsas de monitoria e de tutoria e revoga as disposições em contrário, em especial § 1º do artigo 18 da resolução nº 5/2003-CEPE. Conselho Universitário, Secretaria de Órgãos Colegiados, UFV, 2008. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 4/1971. Dispõe sobre o regulamento da monitoria. Coordenação de Ensino Pesquisa e Extensão, UFV, 1971. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 17/1991. Aprova o regulamento das atividades de monitoria da Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Coordenação de Ensino Pesquisa e Extensão, UFV, 1991. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 1/1993. Altera o dispositivo no item 1 do requerimento de inscrição para concurso de seleção de monitores que consta da resolução nº 17/91, que passa a vigorar conforme o anexo desta resolução. Coordenação de Ensino Pesquisa e Extensão, UFV, 1993. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 5/2003. Aprova o regulamento das atividades de monitoria da Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Conselho de Ensino Pesquisa e Extensão, UFV, 2003. [ Links ]

UFV. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 3/2019. Aprova o funcionamento do programa de monitoria da Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Conselho de Ensino Pesquisa e Extensão, UFV, 2019. [ Links ]

2A simplified version of this text was published in the annals of the event X COPEHE - Congress on Research and Teaching in the History of Education in Minas Gerais.

3On the other hand, there is the teacher education model based on practical rationality, defined by Schön (1992) and resumed by authors such as Pérez Gómez (1992) and Diniz-Pereira (2006). In it, there is an emphasis on practice and the understanding of the teacher as a professional who should guide it from a reflective perspective, in stages such as: reflection on action, reflection on action, and reflection on reflection on action. In the perspective of advancement in relation to this model, Diniz-Pereira (2014) points out the model of critical rationality, which takes into account the socio-historical context, social and political aspects, in addition to considering the role of the teacher in the critical and investigative perspective (CARR; KEMMIS, 1986; DINIZ-PEREIRA, 2014). This understanding moves away from a conservative view in which it is understood that to be a teacher it is enough to be "trained."

5Although Hypolitto (2000) refers to the continuing education of education professionals, his definitions are useful in this work. Marcelo (1999) also cites terms such as continuous, permanent, in-service, "recycling," and capacity building, but opts for the term professional development, as we will explain later.

6Hobold (2018) explains that when talking about "recycling," Garcia (1999) relies on Landsheere (1987).

7Although Imbernón (2016) refers to permanent teacher training in the Spanish context, we can use this definition to understand the meaning of using the term training in the context of the mentoring program.

8However, the COMCRETIDE resolution 02/71, sent to the UFV at the time, dictated the criteria for the implementation of the program and established that the monitoring program would lead to ensuring cooperation in teaching activities and awaken "the taste for the teaching career and for research" (COMCRETIDE, 1971, item 1.1).

9Homem (2014) conducted a study with PhD professors from the Federal University of Mato Grosso, egresses from the monitorship program

Received: May 27, 2022; Accepted: September 28, 2022

texto en

texto en