Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Ensino em Re-Vista

versão On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.28 Uberlândia 2021 Epub 29-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v28a2021-39

ARTIGOS DE DEMANDA CONTÍNUA

Data from a pedagogical activity for the reading of violence images in History Teaching1

2Doutor em História. Docente da Faculdade de Letras e Artes e do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ensino da Universidade do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte (UERN), Mossoró, RN, Brasil. E-mail: paulotamanini@uern.br.

3Mestra em Ensino. Universidade Federal Rural do Semiárido (UFERSA), Mossoró, RN, Brasil. E-mail: ameyremorais@gmail.com.

The article presents a pedagogical activity for the reading of images of a violent nature found in History books. To this end, the activity makes use of an image from the book History Society & Citizenship: La Paraguaya, by the Uruguayan artist Juan Manuel Blanes, dated from 1880. The theoretical contribution about image reading is based on Burke (2004), Santaella (2012) and Bittencourt (2009); as for the use of image as a pedagogical tool in the classroom, this study is based Fonseca (2003), Monteiro, Penna (2011), Alvarenga and Araújo (2006). The didactic activity showed that the images hold the students' attention to the fact that violence exists and is sometimes present, in a subliminal way, including in textbooks.

KEYWORDS: Pedagogical activity; Reading of images; History Teaching; Violence

O artigo apresenta uma atividade pedagógica para a leitura de imagens de cunho violento presentes em livros de História. Para tanto, se serve de uma imagem colhida no livro História Sociedade & Cidadania, La Paraguaya, do artista uruguaio Juan Manuel Blanes, datada do ano de 1880. O aporte teórico acerca da leitura de imagens serve-se de Burke (2004), Santaella (2012) e Bittencourt (2009); sobre o uso da imagem como ferramenta pedagógica em sala de aula, referencia-se em Fonseca (2003), Monteiro e Penna (2011), Alvarenga e Araújo (2006). A atividade didática mostrou que as imagens prendem a atenção do alunado para o fato de a violência existir e estar presente, por vezes, de modo, subliminar, inclusive nos livros didáticos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Atividade pedagógica; Leitura de imagens; Ensino de História; Violência

El artículo presenta una actividad pedagógica para la lectura de imágenes de carácter violento presentes en los libros de historia. Para eso, utiliza una imagen del libro History Society & Citizenship: La Paraguaya, del artista uruguayo Juan Manuel Blanes, fechada en 1880. La contribución teórica sobre la lectura de imágenes utiliza Burke (2004), Santaella (2012) y Bittencourt (2009); sobre el uso de la imagen como herramienta pedagógica en el aula, consulte Fonseca (2003), Monteiro, Penna (2011), Alvarenga y Araújo (2006). La actividad didáctica mostró que las imágenes atraen la atención de los estudiantes sobre el hecho de que la violencia existe y está presente de manera subliminal, a veces en los libros de texto.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Actividad pedagógica; Lectura de imágenes; Enseñanza de historia; Violencia

Introduction

Occupying an exponential place in communication, interactions and exchange of knowledge, images also enter the classroom as one of the facilitating elements of didactics. In such a singular moment when instant messages are pontified, and when visuality seems to replace writing forms, teaching informational History without following the informational load of images might reinforce the fantasy that History, while dealing with the past, has ceased to be interested in present things. Breaking paradigms, History teaching increasingly tries to make use of updated information tools to talk about the past, as well as to discuss, analize, investigate and construct narratives.

Reading is certainly a way to decode, decipher, and interpret signs. If the vast majority say they are literate in written texts, many others find it challenging when faced with figures, images, drawings, icons etc., because they only see the images, but do not read them. When analyzed in detail, the images are perceived as more than an addendum to the written text; they are forms of representation and comprehension of the world that reach textbooks in order to additionally teach. In this sense, the training of Education professionals for a reading concerning visual content becomes urgent, so that they can successfully perform one of their most important purposes: to inform, instruct, say, educate.

This article addresses this gap and tries to reflect on how images can be interpreted, read, assimilated, hermeneuticized, deciphered in their visual content. In the school environment, the use of images has demanded specific treatment because they are potential mediators of knowledge. That is because educating the eyes to facilitate the reading and interpretation of the past involves reflecting on how the visual contents that portray the past are approached.

In order to transform the classroom into a favorable space for the applicability of images as a form of dynamic, meaningful, and engaging knowledge, we thought of a pedagogical activity to deal with the reading of violent images in History Teaching. To this end, we used La Paraguaya, a work by the Uruguayan artist Juan Manuel Blanes, dated 1880, available in high school History textbooks.

Along with the image, we thought of a questionnaire with structured questions to accompany the process of reading images without running the risk of deviations, guesswork, subjectivation, or excesses that would escape the scope of the proposal. The inventoried answers give an idea of how the students deal with the illustrations present in the textbooks.

The classroom as a space of pedagogical activity for the reading of images in History Teaching.

The classroom is also a place dedicated to cultural and formative practices, where techniques and skills are developed in addition to the creativity of teachers and students. Pedagogically, it can also be understood as a space of formation in which the didactic activities concern the actions of students and teachers who associate for mutual growth. To unveil what is inside this place of cultivation and construction of knowledge is to enter a world full of possibilities for pedagogical creations and experimentation. It follows that, at school, while teachers understand the idea of the classroom as a space of pedagogical activity for reading images, lessons can be taught approaching the visual to mediate the knowledge proposed by textbooks.

As an expression of human culture, the image became one of the first attempts to communicate and record everyday life; one of the ways of giving meaning to the world, one of the ways of narrating events within a spatial and chronological framework. Therefore, the image, from the beginning, was seen as an element possessing information that needed to be read in its functional aspects and not only appreciated in its aesthetics. Because it can be interpreted, it was necessary to train professionals who could look at the image as an artifact that makes use of the symbolic to express words. Subsequently, the imagery contents were resized to the category of texts no longer having only peripheral functions such as merely reinforcing what was already said, as described by the sentences and paragraphs, in the textbooks, for example.

In this combination and partnership, textbooks present multiple forms of writing in which the discursive and the imagery mutually engage in the responsibility of teaching. Among the new languages, iconography has positioned itself as a promising way that facilitates learning. Developing students’ and teachers' ability to challenge the images critically has been a daunting task to be faced; enabling them theoretically and methodologically for this new didactic format is also a relevant concern.

Many images depicting violent conflicts today are toned down, because, as some people think, explicitly exposing violence has been agreed upon as an effort at civility. However, violence has existed and exists under different natures, degrees, representations and intensifications, including in textbooks. The books speak of violence, show it by figures, illustrations, and photographs. Violence is constantly present and represented in certain illustrations in the many pages of the textbooks. Therefore, the teacher as a learning mediator, knowing of its existence in the pages of textbooks, can use the visual contents as tools that encourage critical reading, reallocating the imagery content beyond the figurative component.

To give concreteness and to exemplify what has been exposed so far, we present the canvas La Paraguaya:

The image above, entitled La Paraguaya, is an oil on canvas by Juan Manuel Blanes, from 1880, housed in the National Museum of Visual Arts, in Montevideo, Uruguay, and which, in Brazil, serves as an illustration for a History textbook, edited by the publisher FTD. Blanes' work depicts a battlefield in whose center is a female Latin American figure in typically indigenous robes, crestfallen, saddened, surrounded by corpses, vultures; in another frame, an open book and a gun remain visible. In the second plane, added to the inert bodies, a kind of chariot shattered, covered by the shadow of the birds of prey, makes the scenery even more desolate. Each part of the scene portrayed there, seen in isolation, is part of a plot that added to the others forms an imagery record of a historiographical nature, the result of Blanes' perception of "what writing cannot alone enunciate" (BURKE, 2004, p. 38, our translation).

Once exposed, the integrity of the image, the imagery whole incited in the students the emergence of investigative questions, such as: what would have motivated that conflict? Why is the woman portrayed there standing out in the painting? Had she suffered some kind of violence, which one? How does historiography approach the presence of women in these war conflicts? Besides the woman, what other highlights can be noticed?

From the perspective that the image was observed and read as a source that incited questions, it is observed that each frame that was added and joined to the others, like a mosaic, collectively narrates an episode, a scene. Thus, each part of the image concerns an episode and an instant that plots an elaborate narrative employing shapes, colors, traces, and shadows, open to the scrutiny of others, like sources to be investigated. Peter Burke points out that every source must suffer the necessary criticism (2004, p. 30) in order not to be unnoticed as a whole.

Although La Paraguaya was initially thought of as a canvas that represented the armed conflict that occurred in South America (1864 - 1870) between Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, today, it illustrates chapter 15 of the History textbook. Like so many other canvases accustomed to the praises of art critics and the delight of refined spectators and exhibition-goers, they now also serve as textbooks sample pieces, figures that illustrate and teach beyond the field of aesthetics; teach about life, the daily lives of others, stir up the perceptions and understandings of students and teachers.

Arranged at the top of the History textbook’s page, La Paraguaya has a simple caption, containing only the artist's name, title, year of production, and technique used, in addition to the museum in which it is safely stored. On the right side of the image, another small text, inside a balloon, catches the reader's attention, on page 262 of the book História Sociedade & Cidadania.

Notice how the painter Juan Manuel Blanes recreated the environment of desolation and losses resulting from the war on Paraguayan soil. Observe also the absence of men alive in the painting, which suggests a fact that actually happened: the high number of casualties recorded in the Paraguayan male population. (BOULOS JUNIOR, 2013, p. 262, our translation)

The author of the textbook, in an attempt to draw the students' attention to the composition of the painting, certifies that La Paraguaya has information, hidden in the details, and that, at times, can be overlooked in a less attentive reading. It is necessary, then, to be focused on the illustration and understand it as an artifact of teaching and learning.

Santaella (2012, p. 34, our translation) when discussing the use of paintings in teaching, recalls that they "no longer enjoy the status almost exclusively of the visual arts world as it was in previous centuries".

Although paintings no longer have this exclusivity, even today, they continue to be important in learning and research environments, especially in the area of History. This is because illustrations, figures, varied image contents are seen as privileged sources of access to the understanding of a past. Even so, they are ambiguous in their meanings because they depend on the interpretation of those who observe them.

Therefore, Blanes' composition gives rise to interpretations that, regardless of being an artistic work, provide varied reflections about human experiences, over a period of time. Even so, investigative curiosity may raise questions of a different nature, for example: about the artist, the historical and political contexts of the production.

But, how could the classroom be transformed into a dynamic space to strengthen History teaching with the use of images? According to Fonseca (2003, p. 101, our translation), “the school being an institution of a social nature, establishes interaction with various groups, subjects, and institutions”. Consequently, it influences and lets itself be influenced by it. The author also points out that the construction of new pedagogical practices for teaching is also responsive to the socio-cultural contexts in which the school is inserted; it results from the understanding of the school as an institution, an appropriate plural environment for the exchange and production of knowledge. Therefore, the school is a sampling field where what is beyond the boundaries of its walls converges. The daily lives of their students’ families, the concerns and responsibilities of the parents, the relations of power and interests that are not always acceptable, the expressions of love and hate that sometimes lead to extreme violence, at school, have repercussions in the speeches, the sayings, and attitudes of their students.

Violent facts, represented by images in History books, demand appropriations, and readings. In this line of thought, teacher’s mediation is crucial for there to be a communion between the words of the image and the external world of the student and the school. If they mean nothing to the student, the images will continue to be just figurines in books, without saying anything, without teaching anything!

Monteiro and Penna (2011), in the book Ensino de História: saberes em lugar de fronteira, presents a discussion on the theoretical-methodological constitution of research aimed at the affinity between teaching and school knowledge in the narratives of the History subject. The author emphasizes the theoretical contributions of the field of Curriculum and Didactics, articulating them with references to History and Rhetoric theories, stating that research on History Teaching is a frontier place, whose production of knowledge comes from dialogues, exchanges and information sharing.

Therefore, the feasibility of a pedagogical activity for reading images is established, because it shows an opportunity for the student to also exercise the sharing of concerns that surround their universe. Students and teachers together and committed to reflecting on a daily life not far from the one that most students live: we are all surrounded by images! They surround us and say something!

According to Fonseca (2003, p. 119), students and teachers, as subjects of pedagogical action, constantly have opportunities to investigate and produce knowledge. Therefore, in the search for dynamism in History classes, teachers must consider how important historical knowledge is for the formation of active citizens in life in society. With the development of participatory postures, History classes can interact and bring curricular content closer to the lived experiences.

Thus, the classroom is currently understood as a favorable space for the development of inclusive and critical pedagogical practices, a place that accommodates teachers and students for the exchange of knowledge, and that, for this reason, a meeting environment is established, in whose enclosure are intended for dynamic experimentation.

Classroom as a space for sharing and perceptions about La Paraguaya

The selection of an image and its respective reading exercise was based on what Bittencourt (2009, p. 368) warned about the pedagogical proposals for the use of iconographic sources in the classroom. She points out that for the organization of studies which have didactic support of image, two questions are essential: how to select images for the work to be developed in the classroom? And, how do you read the imagery content? The author also suggests a script that helps the analysis of the iconographic field in which questions are made from the figurative elements. The proposal favors the students to describe, according to their perceptions, the scenes, and outstanding characters. That is, an activity that registers the individual perception of each student to, posteriorly, be shared and submitted to a collective learning process. The different looks cast on the image, which in this example represents a situation of violence, will culminate in a synthesis elaborated by the members of the pedagogical activity.

The contribution of Santaella (2012, p. 64) about teaching methods using images served to create scripts and to a subsequent division of students in small groups, which facilitated the development of the proposed activities.

Image reading, in this case, was nothing more than a fruitful attempt to practice the intersection of knowledge in the production of another knowledge: to respect the understanding of the other, to accept different opinions, to revere alterity.

In such panorama, the pedagogical activity for reading images has become an exercise in transforming the classroom into a space for the emergence of plural perceptions and the practice of respect with others. While implementing the development of the proposed activities, it was necessary to extract from the students what only they learned about an image. For this purpose, the exercise of criticality must be motivated as Alvarenga and Araújo (2006, p. 140, our translation) emphasize:

It is never too much to emphasize that the reflection, as a way of critically thinking about reality, of looking at it clearly, broadly, and deeply, is of utmost importance for the student's development. That is why it is crucial to encourage and improve this skill. Once portfolios archives of learning focus on the work of students and their reflection on them, it seems pertinent to state that this tool can develop critical thinking and the skills that are the basis of decision-making processes in our lives.

For a reflective process that exercised the criticism of visual contents, several items that contemplate the images were observed: plans, angulations, colors, lines and compositions of the figures.

Let us see, then, the results of the activity applied in a High School History class, from the reading of La Paraguaya.

La Paraguaya who lets herself be revealed and also reveals a little of students

In order to present data of a pedagogical activity on the reading of a violent image, we went to practice in early December 2019. We applied the pedagogical activity for reading images in a class of 2nd year of High School, from a state public school, in the city of Mossoró (RN), the group was composed of thirty-five students aged between 16 and 19 years old. The criterion for choosing the teaching unit was because the school is located in a peripheral neighborhood where the rates of violence are high. Right away, it was intended to observe the reactions of students who experience violence almost on a daily basis, when they encounter images of a violent nature.

The reproduction of La Paraguaya was made available on A4 paper, colored in high resolution so that there was no compromise of the image elements; additionally by a questionnaire with six questions. Succinctly, the class headteacher explained the reason for our visit and requested cooperation from the thirty-five students present.

Having the floor, we described the activity. While the explanation was taking place, we observed the room's environment: the desks were all lined up, having little space for mobility, clarity was not enough, and there was insufficient ventilation. When receiving the paper containing La Paraguaya, the students were instructed to only observe the image for a minute, and then answer the questions given.

The second part of the activity consisted of answering the first two questions individually: a) do you know the image? b) have you heard about the artist Juan Manuel Blanes?

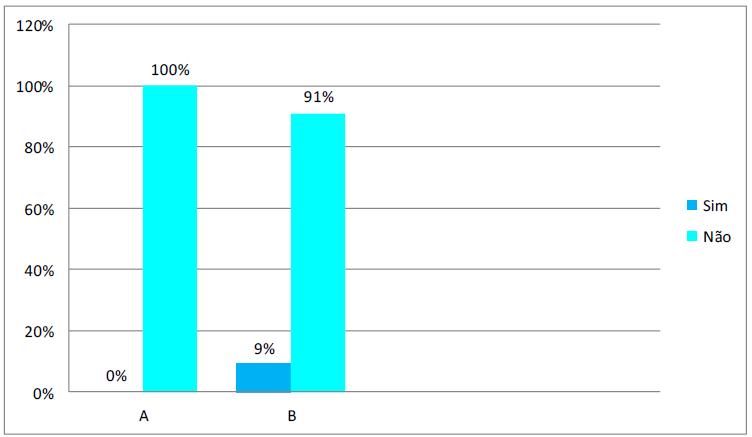

The graph below shows the result of these two questions:

Graph 01 shows that 100% of the class did not know the image, and that 91% had not even heard of it or read anything about the artist. Only 9% said they learned about Juan Manuel Blanes through television documentaries.

Bittencourt (2009, p. 330) points out that when choosing documents to be used as a teaching source, the teacher must consider unprecedented ones because it arouses more interest and curiosity. So, the fact that many students do not know Blanes was interpreted as positive, since the initial curiosity opened the door to other discoveries.

Following the activity, we highlight the way the students stared at the image. We found that La Paraguaya held their attention in such a way that the silence was present without any of them dispersing with parallel conversations with a colleague; there seemed to be only a communion, a dialogue between the student and the image. There seemed to be identification, as recalled by Bittencourt (2009, p. 357, our translation) when discussing the attitudes of History students towards sources familiar to them: “[...] through observation, occurs the identification, and description of the object”.

The next two questions were: what is the main highlight of the image? d) are there any elements you think as violent in the image, and what would that be?

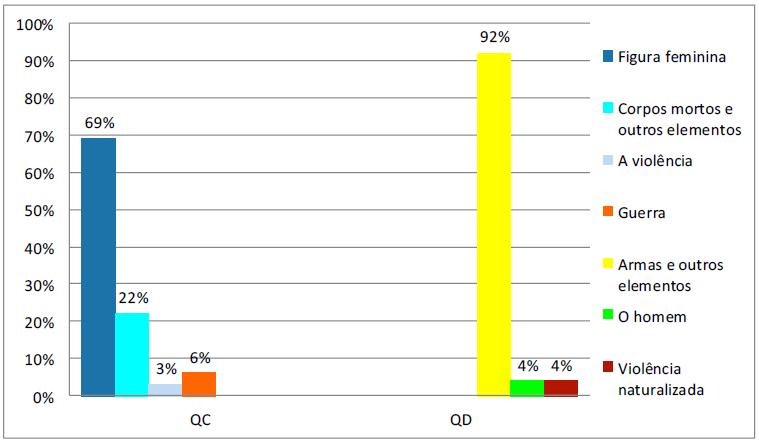

We can see the results presented in the following graph:

As a result of question “C”, 69% of the students pointed out the female figure as the main point of the entire iconographic scene. In their justification, the students highlighted the sadness in the expression that would certainly be associated with the tragic situation of the war; others highlighted the centralized positioning of the women in the whole image; and they also realized that she was the only survivor of the conflict.

Another 22% of the students reported that the inert bodies lying on the floor had more highlights; the remaining 9% presented other frameworks as prominent figures: the flag on the ground, the birds of prey, the place being the scene of the conflict.

According to Santaella (2012, p. 19, our translation), the various apprehensions show the multiple purposes of the gaze: “they can range from sharpening or expanding the perceptual capacity, to confirming a certain sensitivity to reproduce the imaginary”.

When asked if there was any element in the image that they considered violent, 92% of the students answered that the weapons were evident violence artifacts; 4% believed that the human element was the most violent because it caused confrontations and wars. And in the last column, 4% of the students said that in the work La Paraguaya there were no elements of a violent nature. Anyway, whatever the questions, the answers showed ways of understanding the antagonistic violence: from reprobation to apathy.

According to Bittencourt (2009, p. 190, our translation):

It is never too much to emphasize the reflection, as a way of critically thinking about reality, of looking at it clearly, broadly, and deeply, is of utmost importance for the student's development.

In this sense, it would be up to the teacher to contextualize not only the image, but also what students perceived, and what was learned from it. The image, therefore, not only offered signs of representation, but also extracted from the student his understandings, their perceptions of the world, and meanings of existence. A two-way street in which the iconographic content led to discoveries, since it surveyed its viewers who let themselves be revealed by it.

Let us see, then, the results of the last two questions, “E” and “F”, that dealt with the students' feelings regarding the visualization of the violent image. Let us look at the chart below.

The purpose was to measure, beyond the impact, how much the image aroused sensations or impressions in students who already lived in a violent neighborhood. The scene of sadness of the woman featured in the La Paraguaya scene was easily recognized by 35% of the students; 3% reported that conflict environments are sorrowful; 6% said that the scene causes them pain/pity because during the conflict there could probably be innocent people who were killed. Another 3% confirmed that they felt agony; 9% felt astonished, due to the number of inert bodies and only one female figure as the survivor. The feeling of terror amounted to 3%. In cases where the image aroused curiosity, the intriguing sensation represented 3%.

The violent practice seen as something natural in 3% was justified by the fact that their daily lives are more violent than what Blanes portrayed. Those who reported having felt more than one sensation correspond to 23%, while 12% reported not having felt any sensation.

In continuation to the activity, the next question addressed not the image itself, but its impact. When students were asked if La Paraguaya would encourage violence in any way, 27% said YES, since violence always leads to more violence. Contrary to this idea, 58% said NO, because the image itself could not generate violence, since it is only a piece of paper. And 15% said MAYBE, because acts of violence are reflections of the individual's state of mind and viewing images of a violent nature could sharpen violent practices. Although we recognize that the questions asked to measure La Paraguaya's impact on students are too simple, we intended to observe only the impact of the iconographic component and the respective influence on their understandings of the world, their perceptions in the face of the realities they faced.

That said, it was possible to observe the competence of the image as a pedagogical tool. Each part of the imagery component, when subjected to the scrutiny of the gaze, sharpened curiosities, reflections, inquiries, and comparisons. Therefore, it was an experiment that motivated students to give their opinion, to let themselves be known, to reveal a little of their family environments and daily relationships.

Little did they know that when inquiring about La Paraguaya, on the other hand, there was a moment of unveiling their perceptions and understandings of the world, a rediscovery of/on themselves.

Final considerations

Repositioning the visuality at the center of the discussions of the most current pedagogical practices is to reflect on the teaching activity that proves to be dynamic, open to training, and prone to improvements.

For Santaella (2012, p. 80), the act of reading an image must be understood as a deciphering of visual language. So, La Paraguaya contributed for students to feel and know how much they are qualified, or not, concerning the hermeneutics of iconographic artifacts.

Beyond artifacts, images are used as sources for the construction of history. Bittencourt (2009, p. 333) clarifies that the use of images as teaching sources in History classes helps historical thinking and stimulates students' awareness of belonging to facts and time. As a result, History students, present in the pedagogical activity, became participants in a hermeneutic and perceptual process of the present itself.

In this sense, the silent observation of the image during a certain time and the subsequent questionnaire exercised the students in one of the most fundamental teaching and research practices: the observation.

The classroom became a field of practice for reading images that facilitated teaching. The experiences that involved the reading and interpretation exercise of La Paraguaya aimed to bring students closer to the problems of violence that have spread in the world in an overwhelming way, including in the neighborhoods in which they live. The pedagogical activity demonstrated that the classroom can also be an environment for measuring the realities experienced by the student and teacher, preparing them to respond to unexpected situations when required.

Therefore, to discuss the many possibilities of using images in the teaching of history is to contribute to the understanding of man in the world, woven by relationships and the sagacity of standing up to challenges. Because the representations of conflicting realities are part of the chapters that make up the textbooks, it is also up to the teacher to know how to reuse the imagery content, even if of a violent nature, to contemporaneity themes, in order to bring concerns to the present, and listen to possible solutions brought by the speeches of their students.

The interdisciplinarity, which makes itself present and characterizes the most promising teaching, favors a plurality of pedagogical practices and the more effective participation of students. The experience of turning the classroom into an exercise space for image reading favored recreation of the school environment capable of producing knowledge from the life contexts. The students' voices, their impressions, and considerations were taken into account.

When using images as a historical and teaching source in school practice, the history teacher allows their students to reflect on the intentions, the veiled messages, the instituted, the already given. Therefore, knowing how to read an image, a figure, an icon is also to become literate in what goes beyond phrases, long and complex periods. It is to contemplate the figure and extract from it exactly what the sentences and phrases silence.

When reflecting on the image of La Paraguaya, an attempt was made to give visibility to what the students perceived about possible violent acts that the image exposed and how they positioned themselves in the face of the manifestation of violence. From strict reprobation to indifference, students left their impressions as a mirror of their experiences. In this way, the pedagogical activity tried to bring the life of its students to the classroom environment, their impressions, forms, and perceptions of what surrounds them. Again, the exchange and change of experiences of the present became content for discussions for history classes, which by a shallow understanding of the discipline, would only speak of the things of the past. The chronological milestones in this sense are diluted to allow the most relevant themes to be added in the planning of a class that takes into account the current themes.

The didactic activity also showed that the images hold the student's attention to the fact that violence exists and is sometimes present, in a subliminal way, including in textbooks.

If the image has the capacity to reveal the unspoken, the unspeakable to La Paraguaya did not take place at once. The depiction of a saddened woman occupying the center of the screen conveys the consequences of the conflicts. This was what, at first, some students looked, realized, noticed.

However, the figure of La Paraguaya will also look at the student, spy on their reactions, scan their conceptions of the world and how they deal with differences. The illustration will cease to be a common figure and will assume the position of the prototype of a new beginning for denser reflections on the presence of images in textbooks. It will stop being just a drawing to reveal itself as a visual phenomenon capable of shaking the certainties that only books teach with their phrases and writings. What was, at first, a trail, a way of narrating the past about the crudities of life, may represent, in the classroom, in the present, a new way of letting oneself be seen through images.

REFERENCES

ALVARENGA, Georfravia Montoza; ARAÚJO, Zilda Rossi. Portfólio: conceitos básicos e indicações para utilização. Estudos em avaliação educacional. v. 17, nº. 33, jan./abr., 2006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18222/eae173320062131. [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, Circe Maria Fernandes. Ensino de história: fundamentos e métodos. 3ª. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2009. [ Links ]

BOULOS JÚNIOR, Alfredo. História sociedade & cidadania: 2ª ano - Ensino Médio. 1ed. São Paulo: FTD, 2013. [ Links ]

BURKE, Peter. Testemunha ocular: história e imagem. Tradução Vera Maria Xavier dos Santos; revisão técnica Daniel Aarão Reis Filho. Bauru, SP: EDUSC, 2004. [ Links ]

ELLOA, Emmanuel. Entre a transparência e a opacidade - o que a imagem dá a pensar. In: Pensar a imagem/ Emmanuel Alloa (Org). 1ª. ed.; 2ª. reimp. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2017. [ Links ]

BOEHM, Gottfried. Aquilo que se mostra. Sobre a diferença icônica. In: Pensar a imagem/ Emmanuel Alloa (Org). 1ª. ed.; 2ª. reimp. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2017. [ Links ]

FONSECA, Selva Guimarães. Didática e prática de ensino de história: experiências, reflexões e aprendizados. Campinas, SP: Papirus, 2003. Coleção Magistério: Formação e Trabalho Pedagógico. [ Links ]

MONTEIRO, Ana Maria Ferreira da Costa; PENNA, Fernando de Araújo. Ensino de História: saberes em lugar de fronteira. In:_______. Educação e Realidade. Porto Alegre, v.36, nº. 1, p.191-211, jan./abr., 2011. [ Links ]

SANTAELLA, Lucia. Leitura de imagens. São Paulo: Editora Melhoramentos, 2012. [ Links ]

SANTAELLA, Lucia & NÖTH, Winfried. Imagem, cognição, semiótica, mídia. São Paulo: Iluminuras, 1998. [ Links ]

TAMANINI, Paulo Augusto. O Holodomor e a memória da fome dos ucranianos (1931-1933): o ressentimento na História. Projeto História: Revista do Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduação de História, v. 64, 2019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.23925/2176-2767.2019v64p154-184. [ Links ]

TAMANINI, Paulo Augusto; MORAIS, Ana Meyre de. O ensino de História e as imagens postas: a redenção de Caim como fonte de (des) informação sobre a escravidão no Brasil. In: Proposituras: ensino e saberes sob um enfoque interdisciplinar. Paulo Augusto Tamanini. (Org.). São Carlos: Pedro & João Editores, 2018. [ Links ]

Received: June 01, 2020; Accepted: February 01, 2021

texto em

texto em