Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Ensino em Re-Vista

versión On-line ISSN 1983-1730

Ensino em Re-Vista vol.29 Uberlândia 2022 Epub 08-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.14393/er-v29a2022-28

DOSSIER 2: TEACHING AND LEARNING GEOGRAPHY IN TIMES OF HYPERCONNECTIVITY AND POLARIZATION OF IDEAS

Geographic education and remote teaching: the relationship of young schoolchildren with school today1

2PhD in Geography. Federal University of Tocantins, Porto Nacional, TO, Brazil. E-mail: carolinamachado@uft.edu.br.

2Master's in Geography. Federal University of Tocantins, Porto Nacional, TO, Brazil. E-mail: helder.costageo@hotmail.com.

3Master's student in geography. Federal University of Tocantins, Porto Nacional, TO, Brazil. E-mail: anaandreza13@gmail.com.

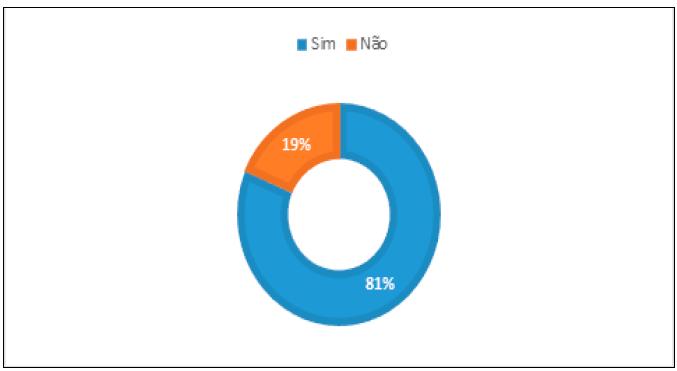

Motivated by knowing how students are dealing with and facing school issues in the context of the pandemic, this article presents reflection on geographic education in remote education and the relationship of young students with school today. The data collected in 2021 and analyzed in this article include 301 students from 6th to 9th grade and from 1st to 3rd grade of high school from 7 schools in the municipalities Almas, Gurupi, Porto Nacional and Palmas. The research revealed that 71% of the students considered the activities performed during the pandemic to be useful, but only 20% considered that remote education was important for learning. The research refuted the hypothesis that students do not want to return to the school environment, since 81% of students wish to return to school activities in person.

KEYWORDS: Geographical education; Remote Teaching; Young students

Impulsionados por conhecer como os estudantes estão lidando e enfrentando as questões escolares no contexto da pandemia, este artigo apresenta reflexão acerca da educação geográfica em ensino remoto e a relação dos jovens escolares com a escola na atualidade. Os dados coletados em 2021 e analisados neste artigo contemplam 301 estudantes do 6º ao 9º ano e da 1ª a 3ª série do ensino médio de 7 escolas nos municípios tocantinenses de Almas, Gurupi, Porto Nacional e Palmas. A pesquisa revelou que 71% dos estudantes consideraram proveitosas as atividades realizadas durante a pandemia, mas apenas 20% consideram que o ensino remoto foi importante para o aprendizado. A pesquisa refutou a hipótese de que os estudantes não queriam retornar ao ambiente escolar, posto que 81% dos estudantes desejam retornar às atividades escolares de forma presencial.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Educação geográfica; Ensino Remoto; Jovens escolares

Impulsado por conocer cómo los estudiantes están lidiando y enfrentando los problemas escolares en el contexto de la pandemia, este artículo presenta una reflexión sobre la educación geográfica en la educación remota y la relación de los jóvenes estudiantes con la escuela en la actualidad. Los datos recogidos en 2021 y analizados en este artículo incluyen a 301 alumnos de 6º a 9º grado y de 1º a 3º de bachillerato de 7 colegios de los municipios de Almas, Gurupi, Porto Nacional y Palmas. La encuesta reveló que el 71% de los estudiantes consideró fructíferas las actividades realizadas durante la pandemia, pero solo el 20% consideró que el aprendizaje a distancia es importante para el aprendizaje. La encuesta refutó la hipótesis de que los estudiantes no quieren regresar ya que el 81% de los estudiantes quieren regresar a las actividades escolares en persona.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Educación geográfica; Enseñanza remota; Escolares jóvenes

Introduction

The pandemic that was imposed on the world in 2020 caused millions of Brazilians to adopt a pattern of confined, isolated behavior with virtual activities. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared on March 11, 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic, illness caused by the new coronavirus (Sars-Cov-2).

The pandemic revealed the precariousness of the structures of the Brazilian health system, the lack of guidelines to deal with the new needs of the population, and the lack of empathy of the federal government in dealing with the brisk scenario of crowded hospitals and without equipment to meet the population. In addition to health issues, the pandemic of the new coronavirus has made even more evident the gulf between the education systems of rich countries and developing countries. The disparities that are made up of the rich from the poor and blacks from whites became more evident in Brazilian education. One of the most serious and structural problems identified in this period was the lack of internet access to attend online classes.

The absence of a nation project by the Federal Government was revealed amid the pandemic. Brazil, unlike many other countries, was not led by a project to contain contagion guided by the federal government, much less witness the presentation of an economic project to Brazil in times of pandemic. The first months were marked by silent government actions to erase the political crisis caused by public health issues.

We witness the production of a new story in the world, in countries and in places. An event that is an expression of the current period of globalization, characterized by the accelerated influence of factors originated above national states.

Given the scenario imposed by the pandemic, some questions worried us and motivated us to carry out the research that, in this text, we present the results. What is the students' assessment of geography classes, held in remote education due to the pandemic? How did students cope and cope with the pandemic and remote education? What were the difficulties and facilities encountered by students to study during the pandemic?

Driven by the right-thinking questions, this article presents reflection on geographic education in remote education and the relationship of young students with school today.

Methodological paths and trajectories

Considering that we work professionally in the municipalities of Almas, Gurupi, Porto Nacional and Palmas and have academic relations with public and private schools in places, we conducted the research with students from the 6th to the 9th year and the 1st to the 3rd year of high school in 7 schools in 4 municipalities of the State of Tocantins/BR, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Source: SERPA, A. A. A. & COPETTI, W. L. F. (organizers), SEPLAN, Department of Planning and Budget of the State of Tocantins. 2021.

FIGURE 1: Location of the search area

Data collection was performed through a form elaborated in a free research management application, which allows the collection of information without the need for a face-to-face meeting with students. The questionnaire included the Term of Free and Informed Consent, which consists of a document elaborated in accessible language, seeking to guide the student participating in the research with a brief and objective description of the research, in addition to the justifications, expected objectives, advantages, disadvantages and risks on the research issues in focus. The questionnaire was prepared without individual identification, thus avoiding the need for approval in the Research Ethics Committee (CEP), as provided for in The Sole Paragraph of Art. 1 of CNS Resolution No. 510/16, which exempts from evaluation of studies that "whose information is aggregated, without possibility of individual identification" (item V of Art. 1 of CNS Resolution No. 510/16).

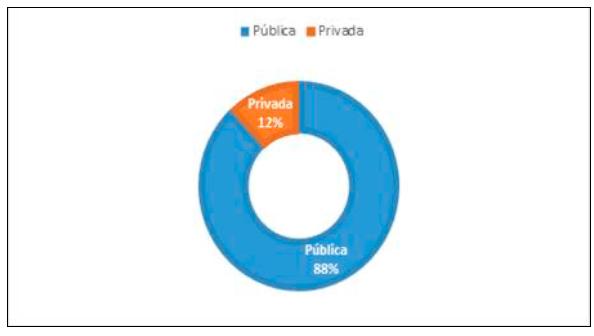

Data collection was available for fifteen consecutive days in August 2021 and the dissemination of the research was carried out with the teachers of the participating schools. The students who participated in the research were mostly from public schools, as shown in Figure 2.

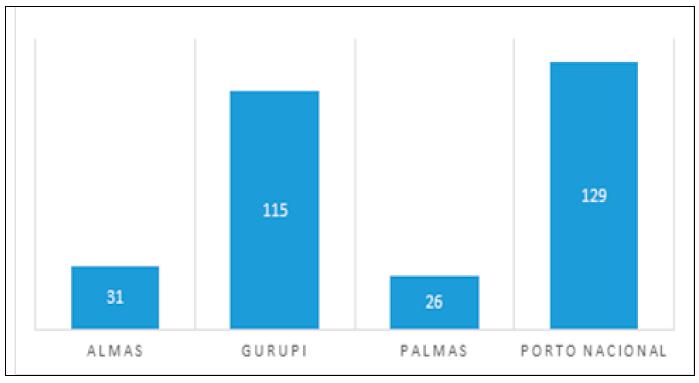

Among the 7 participating schools in the 4 municipalities, we have around one thousand students and obtained a return of 301 responses, according to Figure 3, which presents the distribution of students who responded to the survey by the participating cities.

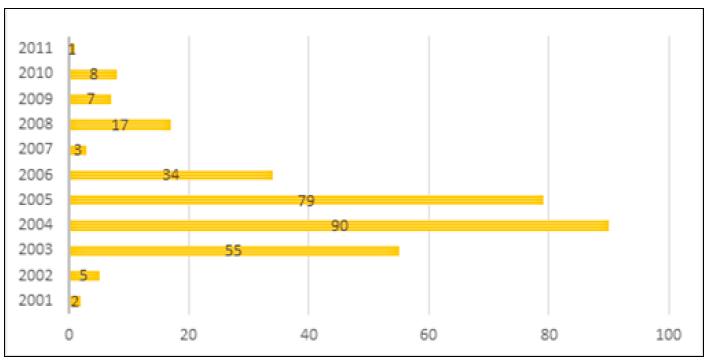

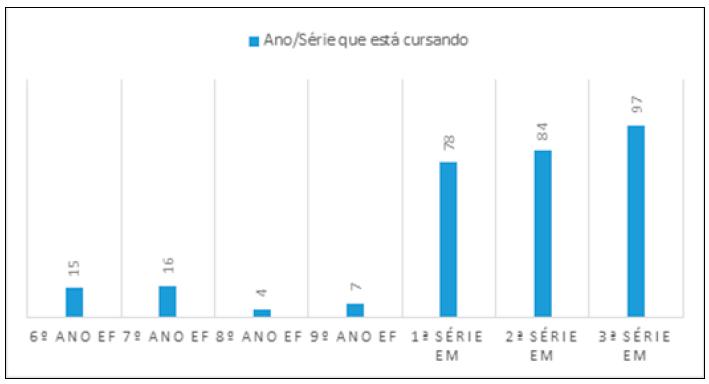

The age of the 301 students who participated in the research ranges from 10 to 20 years, most of which are concentrated between 15 and 18 years old (Figure 4), which is characterized as high school students (Figure 5).

We consider that a study acquires greater credibility when it can combine quantitative and qualitative approaches, because it broadens horizons and allows reflections with greater academic ballast. The quali-quantitative research modality according to Knechtel (2014, p. 106) "interprets quantitative information through numerical symbols and qualitative data through observation, participatory interaction and interpretation of the subjects' discourse", in other words, theoretical-methodological research based on data and allows emphasis analysis on the dialogical approach as a presupposition of learning.

In this sense, quantitative research is linked to the immediate data, which in this research seeks to reflect on the initial guide questions seeking the answers of empirical research added to qualitative reflection that seeks to understand who the students are, what they think, how they are living with remote education and how they are dealing with the pandemic.

Young schoolchildren, remote education and geographical education

Understanding the relationship between students and teaching Geography is not an easy task. Understanding this relationship at the present time is a huge challenge since it is not possible for researchers to be in the locus of research, present together and following the students' reactions to classes, activities, readings and geographical situations placed within the classroom. Although the challenge is herculean, we believe that it is essential to follow the changes that are underway and observe and follow the students as closely as possible to understand the central issue of the research. What is the evaluation of students for geography classes held in remote education, due to the pandemic? This was the essential issue that guided the path of research.

Remote teaching

It is a fact that with the pandemic caused by covid-19, education was strongly affected, mainly due to the instability of social relations and the need to keep activities in remote education. The schools were compelled to adapt their daily lives according to the local reality, in which many units do not have a network of internet access and are not equipped with equipment and technological devices necessary to keep in the face of the needs of remote communication.

Moreira, Henriques and Barros (2020), affirm that the suspension of school activities and the need to ensure the continuity of studies, forced teachers and students to migrate, unexpectedly, to the reality of online activities, transferring and transposing methodologies and pedagogical practices typical of physical learning territories, for what has been called remote emergency teaching.

The suspension of in-person school activities around the world imposed on educational managers in generations and teachers and students in particular the challenge of an adaptation and transformation, until then unimaginable, forcing them to a new educational model, supported by digital technologies and based on the methodologies of online education. (VIEIRA; SILVA, 2020, p. 1014)

For Santos and Zaboroski (2020, p. 43) "the COVID-19 pandemic brought students and teachers a sense of urgency and adaptation (...) and in the face of new challenges, the greatest need is to establish a link between the routine of isolation and the continuity of teaching."

In that scenario arises a question: how were students and teachers able to adapt to the new reality in the face of unpreparedness and the non-technological ability essential to validate the practice of both? The initial answer to this question is established in the practice of improvisation, in view of the so immediate transition from the face-to-face model to the remote model.

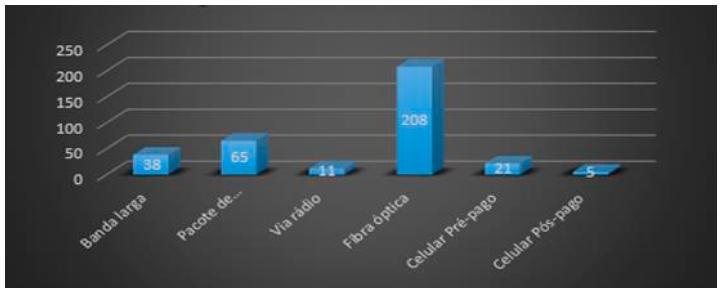

Our hypothesis, when we asked students to access the worldwide internet network, was that they did not have regular access. To our surprise, the students answered, as can be seen in Figure 6, that the vast majority, equivalent to 60% of the interviewees, have access to the internet with fiber optics.

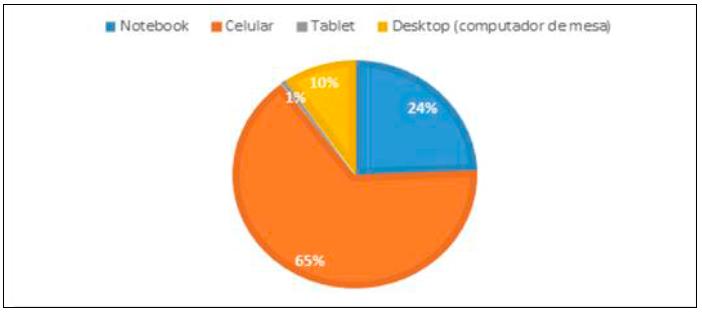

But this data collected and presented in Figure 6 on internet network access is partly invalidated, or at least questioned, given the students' return to the question about the devices used by schools and teachers. The massive return of cell phone use (Figure 7) has put us a research question that could only be solved with face-to-face contact, but as this was not possible, we just want to consider that perhaps students do not have as much clarity of what fiber optic access represents. But regardless of the misconception in returning access, it is fact that students reveal that the most used device is the mobile phone with 65%.

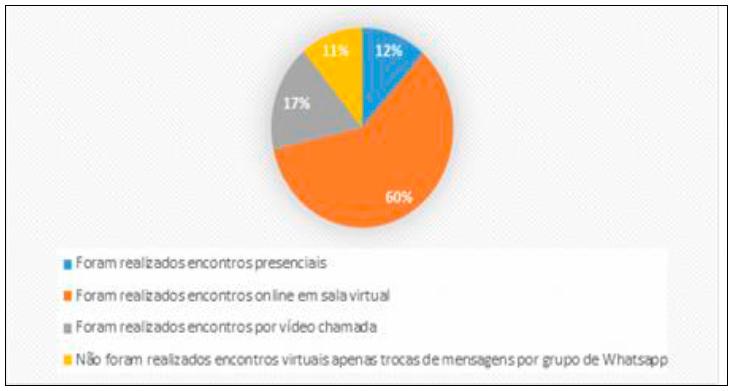

It is a fact that in this period of remote teaching teachers reinvented themselves every day, going over the walls of the classroom to a video camera, and many, turned into true Youtubers5, producing videoclasses and using videoconferencing systems and platforms that were not developed for the classroom but were quickly adapted for synchronous classroom meetings, such as: Google Meet, Zoom, Skype, Hangout, Microsoft Teams among others. Figure 8 presents the reality of meetings between students and teachers that were held virtually for the vast majority in this period.

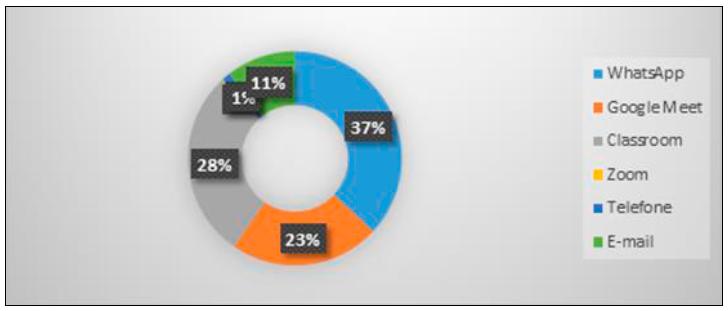

In relation to the media used by the students, Figure 9 shows that most of these contacts between teachers and students were made through the WhatsApp application.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

FIGURE 9: Means of communication used between teachers and students.

Figure 10 shows the forms of activities performed by students during social distancing and with this it is possible to identify that most of the students received study scripts, mainly focused on reading texts and resolutions of printed questions.

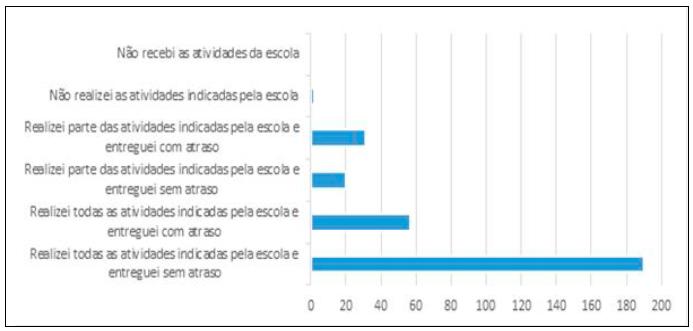

The research allowed identifying the commitment of the students regarding the delivery of activities. Figure 11 shows that most students delivered all activities without delay.

The textbook, which is often the only didactic resource used by the teacher in the classroom during the pandemic, lost the leading role, and was little used (Figure 12), and this is justified because the schools collected the students' books and stored them in schools.

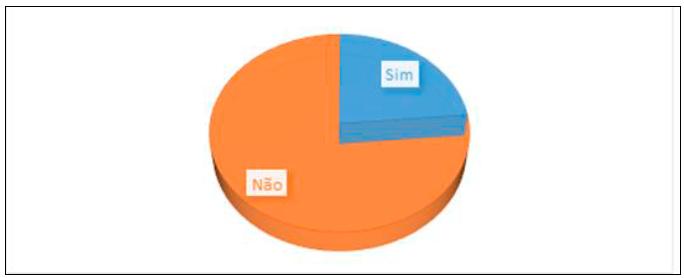

The online questionnaire sought to relate geography teaching to the Covid-19 pandemic. Figure 13 shows that students recognize that through geography it is possible to understand the reality that has plagued the whole world in relation to facing the challenges of the pandemic.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

FIGURE 13: Is it possible to understand the pandemic through geography?

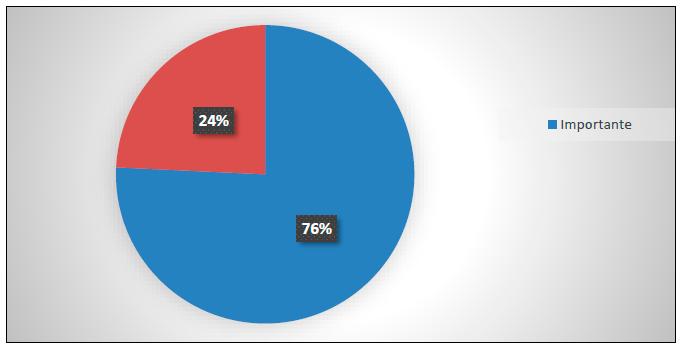

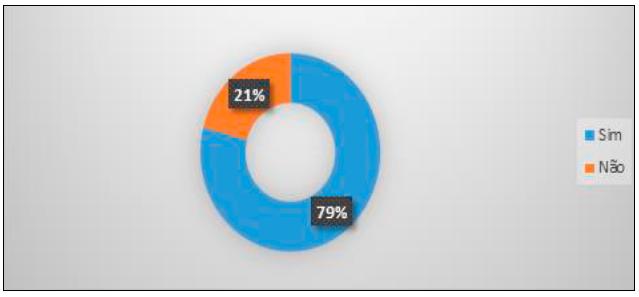

When asked about the importance of geography in remote education, we can observe that Figure 14 reveals that a large majority agree that geography activities performed during the pandemic were beneficial.

When dealing with the experiences of remote activities during the pandemic, about 51% said they did not like the experience (Figure 15).

Figure 16 shows that many students stated that the activities performed during the pandemic helped to keep in touch with the teacher, but a large portion of these students also stated that the activities were tiring. It is also worth mentioning that 20% of students said that remote education was important for learning and surprised us the return of 31% of students who recognize the relevance of activities to keep in touch with the school.

About the students' interest in returning to face-to-face classes, in Figure 17 we can observe that 81% demonstrated the desire to return to school activities in person, which contributes to demystify that students do not like the school. The research confirms that they like the school and miss face-to-face activities.

Silva (2020) reflects that in addition to trying to turn teachers into Youtubers in such a short time, the pandemic also imposed a higher workload and without proper infrastructure, because many teachers and also students had difficulty competing in their own homes for a place reserved for work and that could be used for classes, meetings, meetings and synchronous teaching.

In summary, the situation imposed on teachers and students conditions that in many cases were not overcome in order to be able to follow school activities and for many others were difficulties that, despite being circumvented, hindered the teaching and learning process of children and adolescents in basic education.

Teachers who were not prepared for remote teaching or presented to technological devices in their initial teaching backgrounds had difficulties in structuring online activities. Furthermore, Modelski et. A.M. (2019, p. 06), recalls that in "a society in which information and communication are the main gears that move relationships in the world, the development of skills in teacher education deserves a special look." On the difficulties faced with technological resources, Miranda et al (2020) points out that:

It is necessary to consider that the use of technological tools is a mechanism that allows the expansion of human activities in all social spheres, especially in education. For this reason, the option of more relevance in this pandemic situation is the use of mechanisms present in Distance Education (Distance Education), such as the use of DICT, to act as a means of communication between students and teachers, enabling there to be no interruption in studies, allowing the realization of an emergency Remote Education. (MIRANDA et al, 2020, apud MEDICI; TATTO; 2020 LEAO)

In turn, Manfio (2020) shows that education does not have social isolation and suspension of face-to-face activities, although slow, was overcoming challenges, such as "digital inequalities, the lack of technological mastery of some teachers, the difficulty of school evaluation, school routine at home, among others." In fact, the event represented a challenge to the education system in general.

Geographical education and the meanings of learning

In the last decade there has been an accelerated growth of research on geography teaching. This movement reveals the interest of several researchers about the affirmation of Geography as a curricular component (CAVALCANTI, 2016; PINHEIRO, 2005). At the same time, this period is marked by the expansion of theoretical and methodological discussions that corroborate the construction of a geographical education based on scientific literacy, research, problematization and argumentation.

Geographic education aims at the construction of geographic reasoning by the student (ROQUE ASCENÇÃO, 2020). This reasoning should promote students to understand the world of the present. We are talking about a dynamic, plural, unequal and complex world. A world that needs to be understood by young people. For this reason, geography has much to teach about this world that is in motion and with so many contradictions.

As Castellar (2017) points out, it is in the school that students have the opportunity to develop knowledge historically constructed by science, that is, the school is a place of construction of scientific knowledge and learning. At school and through Geography the student can learn to read, understand and live in this new world, which is increasingly dynamic and diverse. This understanding is marked by the global reality, which unfortunately is increasingly perverse for much of the world's population. According to Callai (2005) the task of Geography at school is to make it possible for the student to know the world of the present.

Today's society has undergone several transformations, especially since people are faced with a multitude of new technical objects. For this reason, we are living in a world with new social relationships, new ways of dealing with objects and new ways of accessing the available information.

Today's globalized world is complex and accumulates and exposes inequalities of every order, especially with regard to aspects of education in Brazil. Faced with so many challenges, basic education today must seek integral formation, that is, to train citizens ready to live in the world of the present. This training will only be possible if we can form an autonomous citizen, with ethical, political, environmental and human awareness, and in this geography has a relevant contribution in the learning process.

Several authors discuss the role of Geography in basic education and for Castellar and Moraes (2011)

(...) the fundamental for school geography is to enable the student to learn in the sense of geographical consciousness, understanding the location of places and phenomena and, from this, being able to reason geographically, understanding the territorial ordering, spatiality and/or territoriality of phenomena, the social scale of analysis. Geographical concepts should be considered permeated by the dynamics of society, because whatever the methodological actions, they must provide the student with conditions to read the world (CASTELLAR & MORAES, 2011, p. 134).

In this sense, the making of geography in school by teachers is directly related to the study of categories and concepts and the use of teaching methodologies capable of helping the student understand the world of the present.

It is essential that this reading of the world be made from the theoretical contributions of this discipline, with the use of categories, concepts and principles of geographical reasoning.

As Castellar and De Paula (2020, p. 317) point out, "Geography is, first of all, a powerful knowledge". The meaning of geography in schools is precisely this, to make the student understand geography as significant and essential for their formation.

Conclusion

Considering that the scenario of schools was challenged by the migration of the face-to-face educational environment to the virtual environment, without having time to adapt the necessary technical structures, an important fact is that students had to assume co-responsibility for their learning.

And that's why the research sought to investigate how students handled and faced remote education. Despite the schools having promoted contact during the pandemic, the activities of this period were not enough to ensure and ensure learning, this was what revealed the research with students. Therefore, it is important that in the scenario of planning the return of activities, schools consider the need to review and evaluate the conditions of the students.

A fact that surprised us with the research was to find that, despite all the mishaps experienced during remote teaching, the school is still the place of learning, and this fact is recognized by the students who wish, for the most part - 71% - to return as soon as possible, to the school benches.

The students pointed out some facilities offered by the remote format, such as the reduction of locomotion, but also highlighted the difficulty of adapting to the environment especially by the restricted interaction between teacher and student and especially the absence of collective coexistence, which is something so characteristic of children and young people and so characteristic of school environments.

The experience experienced during the pandemic with remote education revealed that hybrid teaching allowed schools to promote (even in some places in a very precarious way) the continuity of activities and contact with students.

This teaching model that had already been applied in many schools, and will certainly be part of many institutions. And hybrid teaching with asynchronous remote activities and synchronous face-to-face activities mediated and facilitated by the use of technologies in education and the Internet is a complementary way to offer experiences and dynamics for learning. This brings more autonomy, but it is a fact that schools need technology support for hybrid teaching to work satisfactorily. It is essential that there are computers available for students and teachers to use and be able to carry out the activities in the appropriate way.

Thinking about learning is a current and urgent challenge especially after the experiences experienced in the pandemic process caused by Covid-19. There are many voices of researchers who point out the need to reflect on the school, the meaning of education today and the need to consolidate the knowledge society. In a world in accelerated transformation, where technology imposes rhythms, rules, new flows and processes, thinking about the role of school is a necessity not only for the school community, but for society. And learning is the first agenda. Teaching is inseparable from learning, for which reason the reflection on relationships touch the school and allows consolidating the paths of learning, which emerges from the meaning of the school.

The research allowed to know the situation of some students in schools in Tocantins and revealed the need to think about the resumption of teaching, activities, school and post-pandemic learning. Some questions that arose at the end of the analysis of the results and that to some extent propel us to another investigation are: What is the impact of the knowledge society on post-pandemic school? What is the role of the teacher in the resumption of teaching? How to organize the school as a space that opportunities to learn?

What we learn from remote education and how we will modify our spaces of activity, only a new investigation can show.

Finally, we leave our desire for the future to be better, for our struggles to be fairer and for our schools to be able to affect the sense of learning that we want so much and for which we fight, after all the school is the place of formation, learning, the consolidation of a plural, just, democratic, inclusive and solidary society.

REFERENCES

CALLAI, Helena Copetti. Aprendendo a ler o mundo: a geografia nos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental. Cadernos Cedes, v. 25, n. 66, p. 227-247, 2005. [ Links ]

CASTELLAR, S. M. V. Cartografia escolar e o pensamento espacial fortalecendo o conhecimento geográfico. Revista Brasileira de Educação em Geografia, v. 7, n. 13, p. 207-232, 2017. Disponível em: https://www.revistaedugeo.com.br/ojs/index.php/revistaedugeo/article/view/494. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

CASTELLAR, S. M. V.; DE PAULA, I. R. O papel do pensamento espacial na construção do raciocínio geográfico. Revista Brasileira de Educação em Geografia, v. 10, n. 19, p. 294-322, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.revistaedugeo.com.br/ojs/index.php/revistaedugeo/article/view/922. Acesso em: 18 set. 2021. [ Links ]

CASTELLAR, S. M. V.; MORAES, Jerusa Vilhena. Ensino de Geografia. São Paulo: Cengage Learning. 2011. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTI, Lana de Souza. Para onde estão indo as investigações sobre o ensino de Geografia no Brasil? Um olhar sobre elementos da pesquisa e do lugar que ela ocupa nesse campo. Boletim Goiano de Geografia. V. 36, N. 3, Goiânia: set/dez. 2016. Disponível em https://doi.org/10.5216/bgg.v36i3.44546. Acesso em: 27 set. de 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5216/bgg.v36i3.44546. [ Links ]

KNECHTEL, M R. Metodologia da pesquisa em educação: uma abordagem teórico-prática dialogada. Curitiba: Intersaberes, 2014. [ Links ]

MODELSKI, D.; GIRAFFA, L. M. M.; CASARTELLI, A. O. Tecnologias digitais, formação docente e práticas pedagógicas. Revista Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 45, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/ep/a/qGwHqPyjqbw5JxvSCnkVrNC/?lang=pt&format=pdf. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

MANFIO, V. O ensino de geografia na pandemia covid-19: uma análise da perspectiva do lugar através de histórias em quadrinhos pelos alunos da escola municipal de ensino fundamental professora Cândida Zasso de Nova Palma - RS. Disciplinarum Scientia. Série: Ciências Humanas, Santa Maria, v. 21, n. 2, p. 133-144, 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufn.edu.br/index.php/disciplinarumCH/article/view/3424. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

MIRANDA. K. K. C. de O. et al. Aulas remotas em tempo de pandemia: desafios e percepções de professores e alunos. VII Congresso Nacional de Educação. Centro Cultural de Exposição Ruth Cardoso. Maceió - AL. Out. 2020. Disponível em: https://editorarealize.com.br/editora/anais/conedu/2020/TRABALHO_EV140_MD1_SA_ID5382_03092020142029.pdf. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, J. A. M.; HENRIQUES, S.; BARROS, D. Transitando de um ensino remoto emergencial para uma educação digital em rede, em tempos de pandemia. Revista Diologia. São Paulo, n. 34. p. 351-364, janeiro/abril de 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicos.uninove.br/dialogia/article/view/17123. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

PINHEIRO, Antonio Carlos. O ensino de Geografia no Brasil - Catálogo de dissertações e teses (1967-2003). Goiânia: Editora Vieira: 2005. [ Links ]

ROQUE ASCENÇÃO, V. de O. A base nacional comum curricular e a produção de práticas pedagógicas para a geografia escolar: desdobramentos na formação docente. Revista Brasileira de Educação em Geografia, v. 10, n. 19, p. 173-197, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.revistaedugeo.com.br/ojs/index.php/revistaedugeo/article/view/915. Acesso em: 11 set. 2021. [ Links ]

SILVA, J. S. O ensino remoto emergencial em contexto da pandemia. Abril, 2020. Disponível em: https://ufmg.br/comunicacao/noticias/ensino-remoto-emergencial-em-contexto-depandemia. Acesso em 22 set. 2021. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, M. F.; SILVA, C. M. S. A Educação no contexto da pandemia de COVID-19: uma revisão sistemática de literatura. Brazilian Journal of Computers in Education (Revista Brasileira de Informática na Educação - RBIE), 28, 1013- 1031. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.5753/rbie.2020.28.0.1013. Acesso em: 22 set. 2021. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5753/rbie.2020.28.0.1013. [ Links ]

5The expression Youtubers refers to a content creator subject for the video sharing platform American YouTube. The first youtuber was Jawed Karim Co of the site, which published in 2005 a 19-second video with the title "I at the zoo" (Me at the Zoo), in which he walked watching animals. In that period, being a "youtuber" meant just having an account on the site and uploading simple videos. (SOURCE: https://www.infoescola.com/internet/youtuber/)

Received: October 01, 2021; Accepted: January 01, 2022

texto en

texto en