Introduction

School materials have become relevant to educational practices over the last few centuries. Hence, research has been conducted on these materials, including textbooks2. Rocha and Somoza (2012, p. 28) believe that studies on the history of education allow us to think of the school manual3 as a cultural object that has a variety of “intentions, objectives, regulations” as well as a means of knowledge “about shared values at a given time; about social representations; and about school practices ”.

With the arrival of the court to Brazil in 1808, the Royal Printing was established, whose purpose included the production of materials for public education, although many of these were only translations of foreign books. During this same period, the production of didactic works began to take effect in private publishers, both in the court and in the provinces, which are often more specialized printers in newspapers (BITTENCOURT, 2008). This movement, as well as the search for materials with a language focused on the Brazilian reality, favored the production and publication of national textbooks.

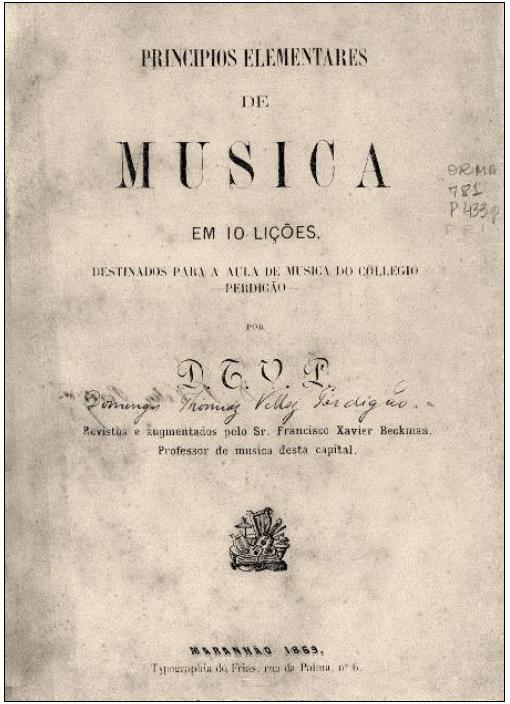

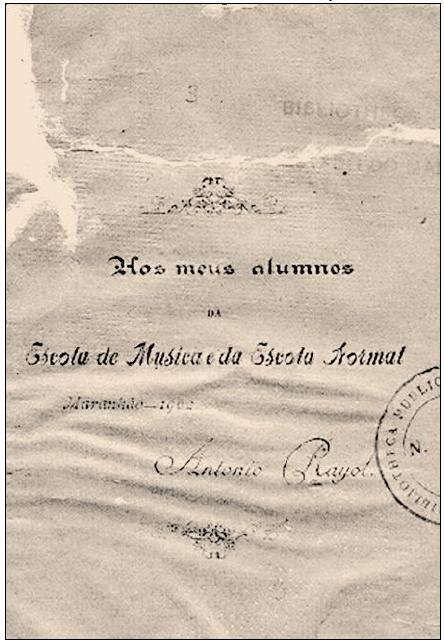

In this context books of Domingos Thomaz Vellez Perdigão and Antonio dos Reis Rayol were produced, two renowned musicians of Maranhão who worked in both private and public “ludovicenses” (people who were born in São Luís, the capital of the State of Maranhão) schools. Therefore, this paper4 aims to analyze such books used in school spaces for music teaching, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in São Luís do Maranhão, taking into account the selected contents, the form of presentation, the public and the purposes for which they were intended. Perdigão's work (1869a), Principios elementares de musica, and Rayol's work (1902), Noções de musica, belong to the Rare Works Collection of the Benedito Leite Public Library in São Luís, being the only schoolbooks found in music until now.

There are still few researches on this topic in Maranhão, among them Dantas Filho (2007, 2014), Cerqueira (2018), Gouveia Neto (2012) and Ferreira (2010). Thus, there is a vast field still to be explored, which justifies the proposal of this article. In this work we use the bibliographical research, with theoretical basis in authors such as Bittencourt (2008), Magalhães (2011), Fagerlande (2011) who deal with textbooks, and De Certeau (2012) that contributes to the understanding of strategies. imposition of the rules, norms and tactics of appropriation of the studied subjects, and the documentary research, whose sources are the regulations of the public instruction, curriculum programs, legislation, messages of the Governors, reports of public instruction and newspapers.

Circulation of school books at the time

With the relevance given in the Empire and, especially, in the Republic to the schoolbook, this became the most published print and the most commercialized among the Brazilian population, surpassing the fiction and the scientific ones. Bittencourt (2008, p. 83) confirms this information when he states that “the circulation of textbooks surpassed all other works of a scholarly character, having a differentiated and, to a certain extent, privileged status, considering

that society began in the world of reading”. Regarding the school textbooks used in nineteenth-century Brazil, these were basically foreign, especially French and Portuguese, because the nationals were not well regarded by some educators5. In this sense, Bittencourt states (2008, p. 71) that "the acceptance and choice by France between sectors of our dominant layers must be understood in the framework of economic and cultural interests established between the two countries [France and Portugal]". Regarding the predominance of Portuguese literature in Brazil until the 19th century, Fagerlande (2011, p. 41) reports that:

Both political and economic reasons prove the strong bond between the two countries; This link is also reflected culturally, as much because the fact that here the musical activities of European origin were much more intense than in other Portuguese colonies, but mainly because most of the information about European music in Brazil passed through Portugal.

Despite this reality, the nationalist spirit defended the production of books focused on the Brazilian reality. By the end of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, national didactic works of music were circulating, such as: Arte da Muzica para uso da mocidade brasileira por hum seu patrício from 1823, anonymous6 author; A arte de solfejar, from 1761, Muzico e moderno Systema para solfejar sem confusão, from 1776, both by Luis Alvares Pinto; Compêndio de música e método de pianoforte, from 1821, by Fr. José Maurício Nunes Garcia (FAGERLANDE, 2011; LANDI, 2006). According to Binder and Castagna (1998, p. 13), the first news “that suggests the presence of a theoretical musical work in Brazil comes from the inventory of Pascoal Delgado, who lived in Santana do Parnaíba (SP) in the first half of the 17th century”. In this inventory three works of organ singing were evaluated. These two authors note that "only the Brazilian musical treaties themselves can inform us which theoretical works were actually known by the Brazilian writers".

For Morgado (2004), the textbooks, in the view of some authors, did not deal exclusively with contents that were part of the teaching programs, but were also disseminators of a culture, an ideology, values in which the writers and/or readers lived, thus being able to propagate these expressions and have control of teaching in schools. De Certeau (2012, p. 215) understands that scripture "becomes power in the hands of a 'bourgeoisie' who places the instrumentality of the letter in the place of the privilege of birth, linked to the hypothesis that the given world is the reason."

Both in the Empire and the early Republic there was a civilizing purpose in formal education, with principles of morality. The model of traditional music teaching, which persisted during the twentieth century - and perhaps even today - emphasizing European society, had a civilizing and reproductive character on the part of the dominant culture. The music used as a civilizing medium met the positivist and republican ideals, as it sought a "better" music in the view of its defenders, as well as a moralizing effect, of order and progress.

These speeches that elevated music to the status of civilizer, essential to a modern (republican) nation, achieved their objectives by looking at the programs of the Primary and Normal Schools. Thus, music, besides softening and balancing the school environment - hygienic music - and serving as sensory education, acquires a position of moral and aesthetic educator, indispensable for modern civilization, according to its interlocutors. It is also a school spectacle, serving to radiate and propagate the republican school for the whole society (MORILA, 2006, p. 87-88).

Thus, the textbooks for music teaching propagated the ideals of culture, society and education of each era. Written texts have always been under control throughout history, whether because of the powers instituted by religion, the state, families, or school, which sought to classify what would or might not be advisable. According to Bitencourt (2008), the books used in the schools in the period defined in this research had to be approved by government agencies, and their surveillance was performed by the Public Instruction Inspectorate of each location. The teacher could be punished, admonished, suspended, and fined if he used any of the forbidden books. The province had little intervention in the private schools, although they were not allowed to use works not recommended either. In this sense, Chopin (2002) complements when he states that the class book is in the articulation between the imposition of the official programs and the singular and concrete speech of the teacher in the classroom, although sometimes of ephemeral nature.

De Certeau (2012, p. 218), in discussing the elements removed or added to a body, as he calls the book, believes that this activity “refers to a code” and “keeps bodies subject to a norm”. This is because bodies confirm these codes, "For where is there, and when, when something of the body is not written, redone, cultivated, identified by the instruments of a social symbolic?" This control fits within the civilizing process, present in both the Empire and the Republic of Brazil, determining what would be best for the population, as well as positivist ideals, in trying to elect what would be “good” for the progress and evolution of the people. However, this author discusses the possibility of tactics developed by the people, as a reaction to the imposition of the authorities.

Context of Maranhenses printings

Hallewell (2012, p. 182-185) states that “by the mid-nineteenth century, book production, as an incidental manifestation of Maranhão prosperity, reached a high standard of technical and aesthetic excellence and sufficient volume to once again draw attention to the provincial editions”. The author highlights two editors of this period: Belarmino de Mattos (Typographia B. de Mattos) and José Maria Corrêa de Frias (Typographia do Frias), who were “friendly rivals, whose continued efforts to surpass each other's achievements were the cause. technical and aesthetic development of book production in Maranhão”. Leão (2013) points out that due to the quality of the production of these two printers, the price was affordable, and the book trade increased, reaching a good range of the population, which contributed to the development of bookstores. The city's newspapers, such as Publicador Maranhense, Liberal and the Diário do Maranhão, announced the sale of schoolbooks in bookstores of the capital Ludovicense or in their own printers.

The two textbooks analyzed here were published by Typographia do Frias, located in São Luís, and advertised in the newspapers of that capital. Principios elementares de musica: em 10 lições by Domingos Thomaz Vellez Perdigão, it was published in 1869. In the book O que se deve ler: Vade-Mecum Bibliographico (1922), by Domingos de Castro Perdigão, is information that his father's book, Domingos Thomaz, had two editions, the second published in 1900 by Luiz Magalhães & Comp7. Regarding the publication of sales of the second edition in the newspapers (see Figure 1), there is reference in several copies of the newspaper Diário do Maranhão, between April 25 and May 29, 1900.

Source: Diário do Maranhão, April 25th 1900.

FIGURE 1: Advertisement of the book Principios elementares de musica, by Perdigão.

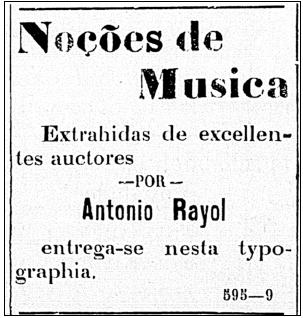

Antonio Rayol's book, also printed in 1902 by the Typographia do Frias, and entitled Noções de musica: extrahidas dos melhores autores, has some references in local newspapers. The first was found in the Diário do Maranhão, November 25, 1902 (p. 2): “A booklet - or art of music - will be printed for learning, work prepared and compiled by Mr. Antonio Rayol, a teacher at Escola Normal and director of state music. It is good news we give to those who dedicate themselves to learning the divine art”. In the copies of the same newspaper, from February to May 1903, is the announcement of the sale of Rayol's book (see Figure 2).

In Pacotilha, December 20, 1902, the release of the book Noções de musica was released. O Federalista of February 5, 1903 published a thanks to Rayol for sending a copy of his book. According to Bittencourt (2008), this was a common practice when the authors themselves were responsible for the publication of their works.

Source: Diário do Maranhão, March 25 1903.

FIGURE 2: Advertisement of the book Noções de musica, by Rayol.

These newspapers allowed, along with other sources, to trace the biographical data of Rayol and Perdigão. There was little information found about this last author. The following reported data were obtained from a text by his son, Perdigão (1922a).

Biographical reports about Perdigão and Rayol

Domingos Thomaz Vellez Perdigão was born in 1842, in São Luís, being the second of the 21 children that his father, Domingos Feliciano Marques Perdigão, of Portuguese descent, had in two marriages: the first in 1840, with his cousin Mrs. Ana Lourença Velêz de Carvalho (eight children), and the second with Mrs. Maria Luiza de Sá (thirteen children). Professionally, he is classified as an industrialist and artist. As for being an industrialist, there was no evidence in any researched document, but as for being an artist, his activities were found as a music teacher (PERDIGÃO, 1922a).

In the Almanak do Diário do Maranhão of 1879, there is an announcement by Domingos Thomaz as a watchmaker, making his services available to society. It included the repair of electric machines, sewing machines, music boxes, pianos, harmonics, organ and stringed instruments. Perdigão (1922b), in the work O que se deve ler: Vade-Mecum Bibliographico, informs that his father gave lessons of violin and piano, besides being musicographer. At Perdigão School, founded by Domingos Feliciano, probably in 1866, Domingos Thomaz taught piano and organ lessons, when he published the book Principios elementares de musica.

A manuscript titled Album de Musica was also written by Perdigão (1869b), where songs of various genres are gathered, such as waltzes, polka, masurcas, schottisch, “quadrilhas”, some for voice, some for guitar and others with melody only. instrument specification to perform them. He was a private tutor of rabeca in the 1870s, in São Luís, and died in 1899, in Portugal. Although no further information is obtained on the life and work of this musician, it is believed that being part of a family, whose father was a renowned teacher and director of schools in the capital of Maranhão, as well as a musician dedicated to this art, Perdigão has had a musical experience and an education that enabled him to have a representation in the Ludovicense artistic milieu.

Antonio dos Reis Rayol, from Maranhão, was a tenor, composer, conductor and violinist, son of Augusto César dos Reis Rayol, descendant of Spaniards, poet and government official, and Leocádia A. Belo Rayol. Different dates around his birth were found in the literature consulted. Jansen (1974), Grupo Nuclear Universitário (1972) and Cacciatore (2005) report the year 1855 and Amaral (2001) on December 23, 1864. However, the date of 1863 is still deduced from the reports on his death. in local newspapers, as they mention that Rayol would turn 41 on December 23, 1904.

Influenced by the numerous lyrical companies that passed through the state, Rayol became interested in singing and won a scholarship to Italy, sponsored by the Count of Leopoldina8. During his stay in Europe, he participated in the Giuseppe Verdi singing contest, during the celebrations for the centenary of Giácomo Rossini, winning fifth place (JANSEN, 1974; CACCIATORE, 2005). Residing in Italy, he composed and conducted, among other musical works, the Missa Solene, which became the most famous of his career. He sent the sheet music for this mass to Carlos Gomes, who, in gratitude, reciprocated by sending the sheet music for his work Condor, with dedication to Rayol.

Back in Brazil, he participated in several concerts, was a music teacher in Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and, in 1900, residing in São Luís, taught at Liceu Maranhense, Normal School and the Night Class of Music9. In 1901 he was appointed director of the newly formed School of Music10. He composed many works of various genres, including the music of the Anthem of Maranhão. As reported in the local newspaper Pacotilha of November 22, 1904, Antonio Rayol died on November 21 of that year, at 23:30 pm, although the date of November 22 is in the Death Book of the Parish of Nossa Senhora da Conceição da Capital. (MARANHÃO, 1894-1910). His death had a great repercussion and at his funeral many people paid their last respects to the one who was consecrated by Maranhão as the first tenor11 of Brazil. During the research, it was identified in local and national newspapers12 the dissemination of Rayol's image covering social, cultural, professional and personal aspects of his life. It is not known whether this space was paid or granted for friendship, but it was important in building its legitimacy.

From the researched documentation, it was found that Perdigão and Rayol were influential and active figures in their time, and frequented the places where the elite circulated, both economic and intellectual. As for participation in popular parties, there are reports in the newspapers of the presence of Rayol in Carnival balls. From the genealogy presented, they were not from a family of great possessions, although they may have acquired material goods as musicians and teachers. It is supposed that the cultural heritage was probably what allowed them to circulate in the social environment and to give them a representation before the society of Maranhão. This gave both musicians the opportunity to write a textbook, of course, among so many other activities and achievements.

Analysis of selected works

The analysis of the works focused on the contents, the form of presentation, the public and the purposes for which they were intended, in this case using the term “objectives”. In Magalhães (2011, p. 16), it is possible to find some of these aspects among the parameters that constitute the analytical structure, used by Anne-Marie Chartier in her research “on the articulation between the book support and the pedagogical rationality”. They are:

The way the manual presents itself (for example, "manual for" a particular class / year, approved by, extended edition, illustrated, etc.); the book setting; the contents; the representation of the school scene; the target audiences; the pedagogical-didactic method that presents.

Perdigão's Principios elementares de musica was published for the purpose of use in Perdigão School music lessons. However, according to newspaper advertising (see Figure 1), the second edition, launched in 1900, already broadened its intended purposes, destining them to the teaching of music of the main Instructional establishments of the Republic, and especially of Maranhão13. The contents of this textbook are set forth in Table 1. Before entering the lessons, Perdigão (1869a, p. 5) defines music as “the art of combining sounds by their elevation and duration,” a definition similar to those found in books circulating in his day.

Table 1: Contents approached at Perdigão´s book

| LIÇÃO | TÍTULO | ASSUNTO | PÁGINA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1ª | Das linhas e espaços | Pauta; linhas suplementares superiores e inferiores. | 5-6 |

| 2ª | Das figuras e seus valores | As sete figuras, suas pausas e valores correspondentes entre elas; ponto de aumento; tresquialtera e sexquialtera (diminuição). | 6-8 |

| 3ª | Dos signos | As sete notas musicais. | 8- 9 |

| 4ª | Das claves | Clave de sol, dó e fá. | 9-10 |

| 5ª | Do compasso e dos tempos | Compasso; Os algarismos do tempo do compasso; Compasso binário, ternário e quaternário; Regência dos três tipos de compassos. | 11-13 |

| 6ª | Dos signaes d’alteração | Sustenido; bemol e bequadro; dobrado sustenido e dobrado bemol. | 14-15 |

| 7ª | Dos tons | Intervalo entre as notas de uma escala; Tons maiores e menores com sustenidos e com bemóis (escalas). | 15-17 |

| 8ª | Das notas de ornamento | Apojectura; Grupo; Trinado; Mordente. | 18-19 |

| 9ª | Da syncopa e ligadura | Sincope e ligadura. | 19-20 |

| 10ª | De alguns signaes acessórios | Firmata-Ponto d’orgão-caldeirão, Da cappo, Al Segno, Intensidade (p, f, pp, ff), crescendo e diminuindo, articulação, abreviatura, bis, casa 1 e 2, andamento ou movimento. | 20-23 |

Source: Table made from Perdigão’s Principios elementares de musica (1869a).

In these lessons presented by Perdigão, it can be observed that the themes are explained in a very simplified way, without entering much in the definitions, nor in the historical origin of each content. Likewise, it does not cover many subjects, dealing with the most basic, necessary for reading and writing traditional music. In the musical education books before and after Perdigão, but coinciding with the period of its circulation, it was observed the existence of several works in this simplified format, often called “artinhas”. It is believed that Perdigão's book, in this context, can be called an “artinha”. However, although concise, it had two editions, which may suggest considerable circulation in the period and relevance in music education.

In all the lessons, examples of traditional musical spelling were found, which illustrate the subjects presented and enable a greater understanding of the contents. Bittencourt (2008, p. 197) reports that this practice of illustrating textbooks was common during the nineteenth century. "Textbook illustrations therefore favored, according to learning conceptions, a way for the student to have contact with more concrete situations not only for children but also for young people." At the end of each lesson, Perdigão prepared a questionnaire. Below is a transcript of the questions from the first lesson as an example of the template used for all the other lessons in the book.

What is music?

How do you count the lines?

How do you count spaces?

What name is given to the five lines?

Apart from these five ordinary ones, are there no others?

Why are they called five ordinary lines?

What are the lines beyond the ordinary called?

Why are the lines, which will be added under or above the ordinary lines, called supplementary or accidental?

What are the supplementary ones to be added above called?

What is the name of the supplementary that will be added below the ordinary lines?

From the analysis of the contents and the proposed exercises, one perceives a priority given to the theoretical subjects, writing and traditional reading, to acquire some knowledge of music, as the author proposes, denoting a more traditional conception of teaching, where these aspects of the theory are relevant before the practical part. Bittencourt (2008) reinforces the idea that the exercises and illustrations of the didactic works demonstrate which teaching methodology this work can contain. In this case, prioritizing the memorization through the questionnaire, we observe again a more traditional methodology, common to the musical teaching of the author's time.

Perdigão made it clear from the back cover of his book (see Figure 3) that it was intended for the music class at Perdigão High School, a private and mainly boys-oriented institution that offered primary and secondary school in a semi-boarding, boarding school and regular school system.

Regarding the purpose of the work, the author explains in the introduction that:

Seeing the need that there were some easy principles for anyone to acquire some knowledge of music; I dedicated myself to the work of arranging these Elementary Principles for my Father's Collegio Perdigão music class; the Snr. Dr. Domingos Feliciano Marques Perdigão: after having carefully read some treatises on the subject; And with some practice, which I have acquired by teaching the little I know of this beautiful art, I have organized them into ten lessons, simplifying everything that I could. However, I could not help showing this little work to Mr. Francisco Xavier Beckman, my music master, and asking him to correct it; to which he willingly agreed, not only making some amendments, but also augmenting some; for that I confess gratitude (PERDIGÃO, 1869a, p. 3).

He ended this part by making explicit the purpose of the book's publication: “the use of the Collegio disciples, and their advancement in the shortest possible time. If the result is such, as I hope, I will have achieved the end I want, and my desires will be fully fulfilled” (PERDIGÃO, 1869a, p. 3). Thus, Perdigão had no intention of writing a bulky textbook, but a material that could be easily understood by the students and achieved a satisfactory result to what the school intended in a not too long period. Chopin (2002, p. 21) states that “the manual can spread very different discourses, according to the times and / or countries: it can be the product of free competition between private companies [...]; on the contrary, it can [...] represent and develop the [...] discourse of the institution”.

As already mentioned, the contents of textbooks often dealt with the same contents as the curriculum. However, it was not found, in this research, the relation of the music contents that, according to the government teaching programs, should be worked in the classroom during the Perdigão period. Even so, through the subjects dealt with in his book, it is possible to have the idea of what was considered by the teachers as relevant to the teaching of music, and that, consequently, was used at Perdigão School.

In Noções de musica: extrahidas dos melhores auctores (1902), Rayol's subjects (TABLE 2) cover various themes and historical explanations, even if they are not very extensive. For Dantas Filho (2007), the entire content of the book could be grouped into the following segments: introductory elements, basic formation and complementary elements of musical formation.

TABLE 2: Contents covered in Rayol’s book

| TITLE | SUBJECT | PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Music: its origin and importance | Definition of music, importance of music among the arts, and some characteristics of music in different periods. | 11-14 |

| Division of music | Theoretical and practical music; melody, harmony and rhythm. | 14-18 |

| Subdivision | The subdivision of music (hall, military, religious, etc.). | 18-20 |

| Sound | Definition of sound, its classification, the vibrations. | 20-21 |

| Intervals | Definition and classification of the intervals. | 22 |

| Acoustics | Definition and function of acoustics. | 22 |

| Tuning fork | Definition of tuning fork. | 23 |

| Musical sheet or pentagrama and spaces | Sheet’s lines and spaces, suplementary lines. | 23 |

| Notes and its origins | Mentions the musical notes and the origin of their nomenclature. | 24-25 |

| Keys (its origins) | Explains the origin and types of claves. | 26 |

| Accidents | Explains the function and the types of acidentes. | 26 |

| Compass | Definition and types of compass. | 26-27 |

| Modes | Definition and types of modes. | 28 |

| Chimerics | Definition of chimerics. | 28 |

| Signs | Definition of signs. | 28 |

| Genres | Diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic sounds. | 29 |

| Systems | Explanation of systems. | 29 |

| Syncopes | Meaning and types of syncopes. | 30 |

| Tempos | Explains the correct tempo to play the music. | 30-31 |

| Setbacks | Definition of contratempo. | 32 |

| Tone | Explanation and classification of tone (major, minor, etc.). | 32-33 |

| Commas | Definition of coma. | 33 |

| Intonation | Definition of intonation. | 34 |

| Sing | Definition and rules to sing. | 34-35 |

| Solfege | Definition of solfege. | 35 |

| Read music | Definition (metric Reading) and explanation on how to perform. | 35-36 |

| Breathing | Definition of breathing. | 36 |

| Transposition | Function of transposition and its performance. | 37 |

| Scale (Its etymology) | Definition and explanations of scales. | 37 |

| Grammar of music | Definition and rules for its performance. | 38-39 |

| Musical language | Gramática, poesia e retórica. Grammar, poetry and rhetoric. | 39 |

| Composition | Definition of composition. | 39 |

| Voices | Definition, classification of voices and examples of renowned singers. | 40-45 |

| Explanation: about music, instruments and some useful things. | Different musical genres, musical instruments, conservatories, other terms. | 45-56 |

Source: Table made from Rayol’s Noções de Musica (1902).

The lack of illustrations of musical spelling is another differential concerning Perdigão's work. In his book, Rayol states that the work was incomplete, having to supply it with his practice, but hoped readers would understand the flaws. The author clarifies that there was no musical typography, and asked readers to remember that the book was exclusively for his students. As he suggests, the absence of musical examples would have been due to the lack of typographic resources of the time, although, approximately 34 years earlier, Perdigão's book, printed by the same typography, that of Frias, had several illustrated examples. Hallewell (2012) reports that the quality of printers in Maranhão was superior to the work of any other performed by the court. Bittencourt (2008) reports that O Livro do povo, printed by Frias in 1861, had many illustrated pages. Probably, in Rayol's period, typography no longer had the same conditions as before printing.

Another point observed corresponds to the fact that Noções de musica has no exercises on the subjects to be studied. It is also noteworthy the introduction of subjects with musical spelling points, such as staff, figures, keys, addressed only in the eighth part of the work, as well as aspects related to perception, such as sound, acoustics and intervals, themes relevant to be addressed before entering the writing and reading part. Like Perdigão, in the opening pages, Rayol makes clear the end of his book and to whom it is intended.

The notions that I took the trouble to write to start my disciples in the mysterious range of Music, which I now dare to publish under the heading of - Noções de Musica-, are but a slight compilation of how much I found quite aesthetic and indispensable for the end. the one you propose to me (RAYOL, 1902, p. 6).

As a teacher at the Normal School and the Music School, Rayol intended his work to meet the needs of students at these institutions (see Figure 4). However, the publication of the book and the advertisements in the local newspapers of the time may have favored a wider audience outside the proposed schools.

Rayol (1902, p. 6) stated his mission in a phrase by Mr. Fetis: “Propagating the art I cultivate - this is my vocation and I cannot resist it - everything that addresses this fin is essentially good”. Following this statement, the author wrote a warning and then a text to the readers. These introductory texts in books, such as preface, warning, and introduction, were a dialogue in which the author explained to the teacher his conceptions and how his book should be used in the classroom (BITTENCOURT, 2008).

This work is intended to facilitate the teaching by art of Leopoldo Miguez where the other explanations necessary for the elementary theorical study are found. The study of solfeggio must be done by the Ignacio Porto Alegre Compendiums, found at the National Institute of Music of Rio de Janeiro and by the Claude Auge Compendium of the schools of Pariz (RAYOL, 1902, p. 7).

Rayol's book does not contain all the content broken down into the teaching programs found for the Normal School and Music School14, but the books he recommends to work together in the classroom: Miguez's (19--), Augé (1896) and Porto-Alegre (189-), which complement the subjects required by these programs. Still as director of the Night Class, Rayol spoke about the necessary changes to the teaching of music in the capital, expressing his opinion about the situation found: “Music needs to be developed among us, since for some time there is a great delay especially in the teaching system, completely disregarding the study of solfeggio and rythmica reading” (MARANHÃO, 1901, p. 5). Through this observation, his concern and interest in adopting two books of solfeggio in the classroom is justified. Augé's book (1896) also contained some metric reading (rhythmic reading) exercises. This interest continued in the 1916 Normal School teaching program, which, among the recommended compendiums, cited Miguez's (19--) for music theory and J. Arnoud's for solfeggio (CONGRESSO PEDAGÓGICO, 1922).

The two authors from Maranhão made use of national and foreign authors for a theoretical basis. Perdigão (1869a), in the introduction, explained that he read other treatises of music, but without specifying them, and allied his experience as a teacher, even though he acknowledged that his knowledge was little. In addition, he submitted the work to the evaluation of his teacher Francisco Xavier Beckman, who, in addition to correcting it, contributed to the addition of some points. Rayol (1902), in turn, in the section dedicated to “readers”, referred twice to consulting other authors. In the first, he recognized that he lacked the skills to produce a work, and that he had the resources of transcendent geniuses, from whom he could understand his appreciations, expounding them as they think, hoping that his students would enjoy the same sensations he obtained. In the second, he said he trusted the authorities he consulted: Savard, Choron, Fayolle, Artusi, Rousseau, Cattaneo, and Rafael Machado, from whose dictionary he copied most of the definitions. The title of the work already clarifies this query, as it includes the extracted word, Noções de musica: extrahidas dos melhores auctores. The mention of the use of other authors confirms the aforementioned observation by Binder and Castagna (1998) that, from the written text itself, it is possible to discover which works were actually known by Brazilian writers.

Since there was no access to the other books Rayol consulted, the boundary between the authors' citations and what he complemented cannot be affirmed. Probably the singing part, where he details the physical posture and the use of the breathing apparatus for the performer to achieve the best voice output, must have been the account of his practice as a lyrical tenor, which was his specialty. Although Perdigão and Rayol use other authors, their practice remains present in their discourses, since “tactics form a field of operations within which theory production is also developed. [...] The narrativization of practices would be a textual 'way of doing', with its own procedures and tactics” (DE CERTEAU, 2012, p. 141).

Thus, certain similarities between the books studied are perceived. This assumption is observed when some aspects were analyzed, such as the contents worked, the probable teaching method adopted, the diffusion of European culture. Note also the representation they give us about the context of music teaching at the time. Once again, we look at these sources, elaborating a narrative that tries to represent the context of the period, from other narratives and representations. As stated in this article, the use of textbooks in public and private education should be approved by government agencies. No reference document authorizing the use of Perdigão and Rayol's books was found, but it is believed that they were approved by this body, as Rayol's was applied to the Normal and Music Schools, both state-owned institutions, and Perdigão's was reproduced in two editions, one being autographed and donated by his son, Domingos Perdigão, to the State Public Library in 1899.

Although only two textbooks of music from Maranhão authors were found, one cannot disregard the existence of others, since several schools offered music teaching and there were many private teachers. Elpídio Pereira, composer and violinist from Maranhão, in his book A música, o consulado e eu, reports that he elaborated a treatise on music theory, related to Rossini's Artimanha de música (PEREIRA, 1957). Given this statement and the possibility of the existence of other materials, one wonders: why are only mentioned in the researched sources the books by Rayol and Perdigão?

Probably one of the factors may be Rayol's musical relevance, as well as the institutions in which he was a teacher, namely the High School, the Normal School and the School of Music. Perdigão, on the other hand, was from a family recognized in the educational environment, since his father was a teacher and founder of two schools and one of his sons was director of the Benedito Leite Library, which may have made possible the dissemination and maintenance of his book. . In relation to these tactics employed, in this case, overcoming the time barrier, De Certeau (2012, p. 97-98) cites, in explaining “the ways of thinking the daily practices of consumers” and how these manners seem to “correspond to the characteristics of cunning and tactical surprises,” such as “skillful gestures of the 'weak' in the order established by the 'strong', the art of striking the other's field, hunter's cunning, maneuverability, polymorphic operations, happy, poetic and warlike findings. ”

Final considerations

The recommendation for printed school material used in the classroom was aimed, preferentially, at foreign books, especially the Portuguese and French, because, although there was a movement for national works, many teachers did not give them due credit. . This preference was part of an elite discourse in favor of economic and cultural interests, and by the civilizing process, based on the European model, as evidenced by Bittencourt (2008). Among these published national works are the school books of Maranhão Domingos Thomaz Vellez Perdigão and Antonio dos Reis Rayol. In this work there was a change in the preference for music books recommended for the Normal School between the 1890s, 1900s and 1910s, when the first ones were essentially foreign and, in the following decades, the presence of national authors was already on the list.

The analysis of Principios elementares de musica: em 10 Lições, written by Perdigão, and Noções de musica: extrahidas dos melhores auctores, considered the contents, the presentation, the audience and the purposes for which they were intended. Perdigão's book, in terms of content, is very succinct, covering the basic elements of music in ten lessons. From the first lesson, the author presented contents of music theory, in a progressive sequence of subjects (from particular to general), with questionnaires that favored memorization, following a more traditional conception of teaching, even for a regular school (primary and secondary school), i. e. without professional intentions. A simpler approach, with illustrations, was used for easy understanding, so that the students of Perdigão School acquired the knowledge of music necessary to perform a reading in the study of instruments in a short period of time.

Rayol's book, on the other hand, contained more content than the previous one, being deeper in the explanations and origin of the themes, although without illustrations and without starting directly with subjects of the musical spelling. Being assigned to two vocational schools, the School of Music and the Normal School, Rayol sought to dig deeper into the mentioned subjects. Like Perdigão's book, it denotes a more traditional conception, since the School of Music taught first the theory and then the instrument, that is, the book was designed for this purpose. It is believed that the two books analyzed were relevant to the constitution of music teaching in Maranhão in the eight hundreds and early Republic.

texto en

texto en